ANORECTAL SYMPTOMS

Despite advances in diagnostic tests, a clinical interview is essential for characterizing the presence and severity of symptoms, establishing rapport with patients, selecting diagnostic tests, and guiding therapy. Although anorectal testing is necessary to diagnose defecatory disorders, a careful interview and examination often suffice for the initial management of fecal incontinence (FI). The emphasis here is on the patient’s dietary and bowel habits, as many anorectal symptoms are a consequence of disordered bowel habits (e.g., FI for semi-formed or liquid stools). When possible, bowel habits should be characterized by bowel diaries and by pictorial stool scales (1). Anorectal symptoms may be broadly characterized into constipation, FI, and anorectal pain.

Constipation

As discussed in the section on bowel disorders, patients may refer to a variety of symptoms by the term “constipation.” Anecdotal experience and some evidence suggest that certain symptoms (e.g., sense of anorectal blockage and anal digitation during defecation) are more suggestive of a defecatory disorder than others (e.g., sense of incomplete evacuation after defecation and excessive straining) (2,3). In addition to impaired rectal emptying, the sense of incomplete evacuation may also reflect rectal hypersensitivity (e.g., irritable bowel syndrome). Other symptoms (e.g., hard and/or infrequent stools) are perhaps more suggestive of normal or slow transit constipation rather than defecatory disorders. As even normal subjects may struggle to expel small hard pellets, difficulty in evacuation of soft, formed, or more so, liquid stools is more suggestive of an evacuation disorder. However, functional defecation disorders often cannot be distinguished from other causes of chronic constipation by symptoms alone. As such, anorectal testing should be considered, particularly in patients who fail to respond to fiber supplementation and empiric laxative therapy.

Fecal incontinence

Fecal incontinence refers to the recurrent uncontrolled passage of liquid or solid fecal material. Although distressing, involuntary passage of flatus alone should not be characterized as FI, because it is difficult to define when the passage of flatus is abnormal (4). Patients should be asked if they have FI, because more than 50% of patients will not disclose the symptom unless specifically asked (5). The frequency, amount (i.e., small stain, moderate amount (i.e., more than a stain but less than a full bowel movement), or a large amount (i.e., full bowel movement)), type of leakage, and presence of urgency should be ascertained. Semi-formed or liquid stools pose a greater threat to pelvic floor continence mechanisms than formed stools, whereas incontinence for solid stool suggests more severe sphincter weakness than for liquid stool. The awareness of the desire to defecate before the incontinent episode is variable, and may also provide clues to pathophysiology. Patients with urge incontinence experience the desire to defecate, but cannot reach the toilet on time. Patients with passive incontinence are not aware of the desire to defecate before the incontinent episode. Patients with urge incontinence have reduced squeeze pressures (6), and/or squeeze duration (7), and/or reduced rectal capacity with rectal hypersensitivity (8), whereas patients with passive incontinence have lower resting pressures (6). Nocturnal incontinence occurs uncommonly in idiopathic FI, and is most frequently encountered in diabetes mellitus and scleroderma.

Anorectal pain

As detailed in the algorithm, anorectal pain can be distinguished into levator ani syndrome and proctalgia fugax by distinctive clinical features. This classification system does not include coccygodynia, which refers to patients with pain and point tenderness of the coccyx (9), as a separate entity. Most patients with rectal, anal, and sacral discomfort have levator rather than coccygeal tenderness (10). There are many similarities between clinical anorectal and urogenital disorders characterized by chronic pain. Although the pathophysiology is largely unclear, tenderness to palpation of pelvic floor muscles in chronic pelvic pain and levator ani syndrome may reflect visceral hyperalgesia and/or increased pelvic floor muscle tension (11). Some patients with levator ani syndrome may have increased anal pressures (12). Finally, there is a strong association between chronic pelvic pain and psychosocial distress on multiple domains (e.g., depression and anxiety, somatisation, and obsessive-compulsive behavior) (13); whether this reflects an underlying cause or an effect of pain is unclear.

REFRACTORY CONSTIPATION AND DIFFICULT DEFECATION

Case history

A 32-year-old office worker is referred to a gastroenterologist by her primary care physician because of a 3-year history of chronic constipation, which has not responded well to therapy (Box 1, Figure 1). She has on average two bowel movements weekly but these are usually small, of hard or normal consistency, and passed with considerable straining. after attempts at defecation, she is left with a sensation of incomplete evacuation. She has not used manual maneuvers to facilitate defecation. She has no abdominal pain, but does experience abdominal bloating on the day before defecation. There has been no rectal bleeding or weight loss. She is otherwise well, with no known systemic diseases associated with constipation, and has had no pregnancies or pelvic or abdominal surgery. She takes no medications for constipation. There is no family history of gastrointestinal disease.

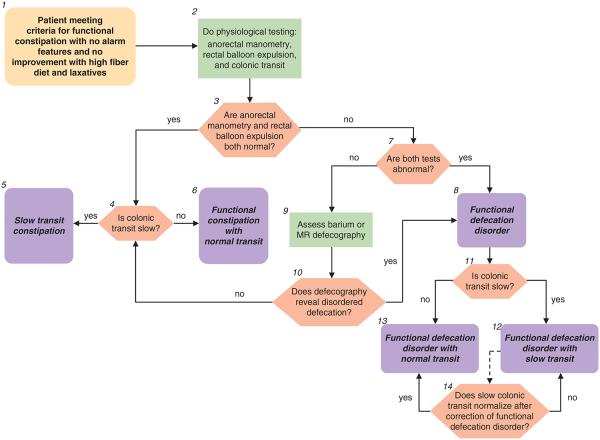

Figure 1. Refractory constipation and difficult defecation.

-

1.For the initial assessment of chronic constipation, and the diagnosis of functional constipation, see the preceding algorithm “chronic constipation”. Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional constipation (1) are: (i) two or more of the following: (a) straining during at least 25% of defecations, (b) lumpy or hard stools in at least 25% of defecations, (c) sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25% of defecations, (d) sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for at least 25% of defecations, (e) manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25% of defecations (e.g., digital evacuations and support of the pelvic floor), (f) fewer than three defecations per week; and (ii) loose stools are rarely present without the use of laxatives; (iii) insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome; (iv) criteria fulfilled for at least 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. The use of a stool diary incorporating the Bristol Stool Form Scale can provide more information regarding stool frequency, consistency and passage. However, in this context as well as the above information, and the presence or absence of abdominal pain linked to the disordered bowel pattern, the history should particularly establish the presence of other relevant symptoms. These include a sensation of incomplete evacuation, any sensation of anorectal obstruction and the use of manual maneuvers to aid evacuation. The absence of “alarm” features should be confirmed, namely: age >50 years, short history (<6 months), family history of colon cancer, blood in stools, and weight loss (2). Patients who fulfill the criteria for functional constipation and those who have not improved with an increase in dietary fiber and the use of simple laxatives (see “chronic constipation” algorithm), and with no alarm features, often warrant further physiological assessment. Although some physicians may, perhaps for medicolegal reasons, opt in this setting to evaluate for colon cancer with imaging or endoscopy, there is no evidence to support this practice in the absence of alarm symptoms as the prevalence of colonic neoplastic lesions at colonoscopy is comparable in patients with vs. without chronic constipation (15).

-

2.The three key physiological investigations are anorectal manometry, the balloon expulsion test, and a colonic transit study. Anorectal manometry is carried out using water perfused or solid-state sensors or more recently by high-resolution manometry. At a minimum, anal-resting and -squeeze pressure, and the recto-anal inhibitory reflex should be assessed during manometry. Recto-anal pressure changes during straining, a maneuver which simulates defecation, should also be assessed when an evacuation disorder is suspected. Anal pressures should preferably be calculated by averaging all four quadrants to account for anal sphincter asymmetry. Variations in patient effort also need to be taken into account. Resting pressures are probably less susceptible to artifact than are squeeze pressures. Squeeze pressure should be measured by asking patients to squeeze (i.e., contract) the sphincter for at least 30 s, and to average pressure over this duration. As anal pressures are affected by age, gender, and technique, measurements ideally should be compared against normal values obtained in age- and gender-matched subjects by the same technique (16-18). The rectal balloon expulsion test, carried out by measuring the time required to expel a rectal balloon filled with 50 ml warm water or air, is a useful, relatively sensitive, and specific test for evacuation disorders (19,20). The balloon inflation volume for this test is not standardized; the balloon is either inflated by a fixed volume, typically 50–60 ml, or until patients experience the desire to defecate. When the balloon is inflated by a fixed volume (e.g., 50–60 ml), as in most laboratories, patients who have reduced rectal sensation may not perceive the desire to defecate, and therefore may be unable to expel a balloon. The performance characteristics of this test vs. defecography were evaluated by a study, in which the balloon was inflated to the volume at which patients experienced the desire to defecate. The normal value depends on the technique. At most centers, >60 s is considered as abnormal. The balloon expulsion test is a useful screening test, but does not define the mechanism of disordered defecation, nor does a normal balloon expulsion study always exclude a functional defecation disorder. Additional research is needed to standardize this test that does not always correlate with other tests of rectal emptying such as defecography and surface electromyography (EMG) recordings of the anal sphincters. Colonic transit is most readily assessed using a radio-opaque marker technique; scintigraphy and more recently, a wireless pH-pressure capsule have also been used to measure transit. Colonic transit measured by these three methods is reasonably comparable. There are several available techniques of measuring transit by radio-opaque markers. In the Hinton technique, a capsule containing 24 radio-opaque markers is given on day 1 and the remaining markers seen on a plain abdominal X-ray on day 6 are counted: <5 markers remaining in the colon is normal, >5 markers scattered throughout the colon = slow transit, and >5 markers in the recto-sigmoid region with a near normal clearance of rest of colon may suggest functional defecation disorder (21). In an alternative approach, which characterizes not only overall but also regional colonic transit, a capsule containing 24 radio-opaque markers is given on days 1, 2, and 3 and remaining markers seen on a plain abdominal X-ray on days 4 and 7 are counted (22). With this technique, a total of >68 markers remaining in the colon is normal whereas >68 markers is slow transit. *Note: Instruct radiology to use high penetration films (110 keV) to reduce radiation exposure; if <34 markers on day 4, then the second X-ray is not required. Have patient avoid laxatives and keep diary of bowel movements for 1 week before, and during, the test to correlate with transit. Colonic transit can also be measured by a wireless motility-pH capsule. In constipated patients, the correlation between colonic transit measured by radio-opaque markers (on day 5) and the capsule is reasonable (correlation coefficient of approximately 0.7) (23). The capsule can also measure colonic motor activity (24). Scintigraphy entails delivering an isotope (generally 99 mTc or 111 In) into the colon by a delayed-release capsule that has a pH-sensitive polymer (methacrylate), which dissolves in the alkaline pH of the distal ileum, releasing the radioisotope within the ascending colon. Then, gamma camera scans taken 4, 24, and, if necessary, 48 h after the isotope was ingested show the colonic distribution of isotope (25). Advantages of scintigraphy are that colonic transit can be assessed in 48 h as opposed to 5–7 days for radio-opaque markers. Also, gastric, small intestinal, and colonic transit can be simultaneously assessed by scintigraphy.

-

3.At anal manometry, the patterns of anal sphincter and rectal pressure changes during attempted defecation are the most relevant parameters in this context. A normal pattern is characterized by increased intrarectal pressure associated with relaxation of the anal sphincter. Abnormal patterns are characterized by lower rectal than anal pressures during expulsion effort, resulting from the inability to generate an adequate propulsive or “pushing” intra-rectal pressure, and/or impaired relaxation or paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter. However, as a proportion of asymptomatic subjects may have an abnormal pattern, it is necessary to interpret this test in the context of clinical features and other test results.

-

4–6.If both anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion are normal, the results of colonic transit testing enable characterization of the disorder as functional constipation with normal or slow transit. The normal values for the radio-opaque marker tests are given above. Some patients with slow and even normal transit constipation have colonic motor dysfunction, perhaps severe enough to be characterized by colonic inertia. On the other hand, slow transit constipation may be associated with normal colonic motor functions, as assessed by intraluminal methods (i.e., a barostat or manometry), or with defecatory disorders (26). Although the diagnostic criteria for colonic inertia are not established, this term refers to reduced contractile responses, measured by manometry and/or a barostat, to physiological (i.e., a meal), and pharmacological stimuli (e.g., bisacodyl and neostigmine) stimuli. Colonic manometry and barostat testing is available at selected centers. The clinical utility of distinguishing between colonic motor dysfunction and inertia is unknown. A hypaque enema should be considered if plain abdominal X-rays suggest megacolon.

-

7,8.Based on results of recent studies, if both manometry and the rectal balloon expulsion test are abnormal, this is sufficient to diagnose a functional defecation disorder (20) In this circumstance imaging (e.g., barium or MR defecography) is not generally required but should be considered if it is necessary to exclude a structural abnormality e.g., enteroceles, intussusception, or clinically significant rectoceles. Although clinical features and digital rectal examination can identify a rectocele, imaging can assess its size and emptying during evacuation. The Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional defecation disorders are: (i) the patient must satisfy diagnostic criteria for functional constipation; (ii) during repeated attempts to defecate, must have at least two of the following: (a) evidence of impaired evacuation, based on balloon expulsion test or imaging, (b) inappropriate contraction of the pelvic floor muscles (i.e., anal sphincter or puborectalis) or <20% relaxation of basal resting sphincter pressure by manometry, imaging or EMG, and (c) inadequate propulsive forces assessed by manometry or imaging; (3) criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. Inappropriate anal contraction is also referred to as dyssynergic defecation.

-

9.If only one of the anorectal manometry and balloon expulsion is abnormal, further testing—barium or magnetic resonance defecography may be used to confirm or exclude the diagnosis. Defecography can detect structural abnormalities (rectocele, enterocele, rectal prolapse, and intussusception) and assess functional parameters (anorectal angle at rest and during straining, perineal descent, anal diameter, indentation of the puborectalis, and amount of rectal and rectocele emptying). Small bowel opacification is required to identify enterocoeles by barium defecography. The diagnostic value of defecography has been questioned primarily because normal ranges for quantified measures are inadequately defined and because some parameters such as the anorectal angle cannot be measured reliably because of variations in rectal contour. Moreover, similar to anorectal manometry, a small fraction of asymptomatic healthy people have features of disordered defecation during proctography. Thus, there is no true gold standard diagnostic test for defecation disorders. Nonetheless, an integrated consideration of tests (i.e., manometry, rectal balloon expulsion, and defecography) together with the clinical features generally suffices to confirm or exclude defecation disorders. Magnetic resonance defecography provides an alternative approach to image anorectal motion and rectal evacuation in real time without radiation exposure. In a controlled study, magnetic resonance defecography identified disturbances of evacuation and/or squeeze in 94% of patients with suspected defecation disorders (26). Whether magnetic resonance defecography will add a new dimension to the morphological and functional assessment of these patients in clinical practice merits appraisal.

-

10.If defecography reveals features of disordered defecation, a diagnosis of a functional defecation disorder can be made. Defecographic features of disordered defecation include less than complete anal opening, impaired puborectalis relaxation or paradoxical puborectalis contraction, reduced or increased perineal descent, and a large (>4 cm) rectocoele, particularly if emptying is incomplete. If defecography is not abnormal, then the patient does not fulfill criteria for the diagnosis of a functional defecation disorder; further diagnosis then depends on the presence or absence of colonic transit delay (see above #4–6).

-

11–13.The presence of a functional defecation disorder does not exclude the diagnosis of slow colonic transit. Thus, depending on the results of the colonic transit study, the patient can be characterized as suffering from a functional defecation disorder with normal or slow colonic transit.

-

14.As well as coexisting with it; however, slow colonic transit may result from a defecation disorder. If it is felt appropriate to distinguish between the two possibilities, the colonic transit evaluation may be repeated after correction of the defecation disorder. If transit normalizes, the presumption is that the delay was secondary to the defecation disorder; if not, the delayed colonic transit is presumed to be a comorbid condition, which may require therapy if there is no clinical improvement with the treatment of functional defecation disorder.

Her physical examination is normal. Digital rectal examination reveals normal anal resting tone and contractile response during squeeze. Simulated evacuation was accompanied not by relaxation but by paradoxical contraction of the puborectalis muscle and no perineal descent. Fiber supplements, PEG laxative and lactulose, prescribed at various times by her primary care physician, make her feel bloated and uncomfortable with no improvement in her constipation (Box 1). Bisacodyl gives her abdominal cramps, and a trial of lubiprostone made her nauseated, with neither improving her bowel habits. At times when she has not moved her bowels for several days she uses a glycerol suppository to aid evacuation.

CBC, ESR, and biochemistry panel, including metabolic screen, arranged by her primary care physician 12 months earlier, were normal. The symptoms were significantly affecting her quality of life and the gastroenterologist decided to arrange for further diagnostic testing. These physiologic tests include assessment of colonic transit, anorectal manometry, and the rectal balloon expulsion test (Box 2). Anorectal manometry demonstrates a recto-anal profile during expulsion efforts that features an inappropriate contraction of the anal sphincter (increase in anal sphincter pressure) despite an adequate propulsive force (intrarectal pressure of 50 mm Hg). Resting and squeeze anal sphincter pressures are 60 (normal 48–90) and 100 (normal 98–220) mm Hg, respectively. Rectal sensory thresholds for first sensation, the desire to defecate, and urgency are 30, 100, and 160 ml respectively; values above approximately 100, 200, and 300 ml for these thresholds are abnormal (14). The balloon expulsion test reveals that the patient is unable to expel the water-filled (50 ml) balloon within 2 min on each of two attempts (normal <60 s). Using the Hinton technique for measuring colonic transit, the patient swallowed a capsule containing 24 radio-opaque markers. after 5 days, an abdominal X-ray obtained in the supine position (110 keV) showed three markers remaining in the sigmoid colon and rectum (normal <5 markers) (Box 3). Th us both anorectal manometry and the balloon expulsion test are abnormal (Boxes 3 and 7). On this basis a diagnosis of a functional defecation disorder is made (Box 8). This disorder is further characterized as functional defecation disorder with normal transit (Boxes 11 and 13).

On this basis the patient is referred to the laboratory for anorectal biofeedback therapy. She undergoes five biofeedback sessions during a 5-week period with a trained therapist. Other centers provide a more intensive program with 2–3 sessions daily over 2 weeks. Using biofeedback, she learns to normalize her defecation profile. She reports significant clinical improvement and is now able to expel the balloon within 20 s.

FECAL INCONTINENCE

Case history

A 60-year-old telephone operator is referred to a gastroenterologist because of FI, which has been present for 2 years. Her usual bowel habit is that she passes 1–2 soft but formed bowel movements daily, feeling satisfied thereafter. Approximately once a week, however, she is incontinent for a small amount of semi-formed stool, perhaps the size of a quarter, often while walking or standing (Box 1, Figure 2). She is aware of the incontinent episode approximately 50% of the time, and there is no associated urgency. She can usually differentiate between the sensation of gas and stool in her rectum, and is often incontinent for flatus. She wears a pantiliner throughout the day, everyday. These symptoms make it difficult for her to continue with her current work, and have significantly affected her quality of life. There is no blood or mucus in the stools and she has no other significant gastrointestinal symptoms. A review of other systems is negative; in particular she has no urinary or neurological symptoms (Box 2). Her dietary history does not reveal symptoms of carbohydrate intolerance. She has no other medical conditions and is taking multivitamins only. The obstetric history is notable for two vaginal deliveries accompanied by episiotomy but no forceps assistance or anal sphincter injury.

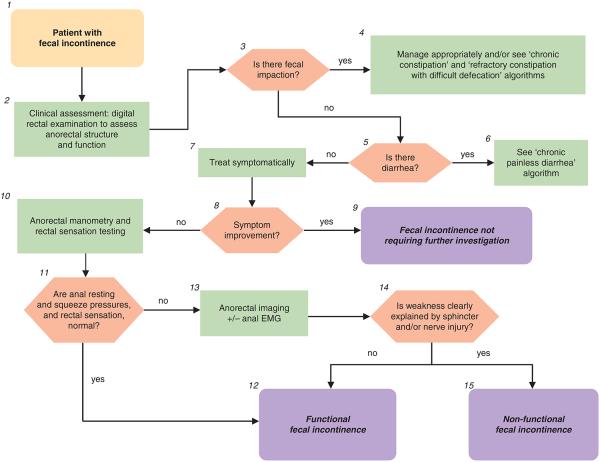

Figure 2. Fecal incontinence.

-

1.Fecal incontinence (FI) is defined as uncontrolled passage of fecal material recurring for at least 3 months in people aged 4 or more years. Leakage of flatus alone should not be characterized as FI. In this context, the FI is assumed to not be associated with known systemic or organic disorders (e.g., dementia, multiple sclerosis, and Crohn’s disease) (27,28).

-

2.The history should determine the duration of symptoms, type of FI, and associated bowel habits; urinary and neurological symptoms should be evaluated (27). Consider possible undiagnosed systemic or organic disorders that can cause FI. Although a spinal cord lesion can cause FI, typically, patients with a spinal cord lesion and FI will have other neurological symptoms and signs of the underlying lesion. Severity is established by consideration of four variables, i.e., frequency, type (i.e., liquid, solid stool, or both), amount (small, moderate, or large) of leakage, and presence/absence of urgency. The physical examination should particularly evaluate the presence of any alarm signs e.g., abdominal mass, evidence of anemia. Where indicated, a neurological examination should be carried out. A careful digital rectal examination is critical to understanding the etiology and for guiding management of FI. This should assess for stool impaction, anal resting tone (patients with markedly reduced tone may have a gaping sphincter), contraction of the external sphincter and puborectalis to voluntary command, and/or dyssynergia during simulated evacuation. In this patient, anal-squeeze response was reduced but the puborectalis lift was preserved, consistent with sphincter but not puborectalis weakness. Dyssynergia refers to impaired relaxation and/or paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter and/or puborectalis muscle and/or reduced perineal descent during simulated evacuation. To evaluate the integrity of the sacral lower motor neuron reflex arc, perianal pinprick sensation, and the anal wink reflex should also be assessed.

-

3.The presence of fecal impaction at digital rectal examination suggests fecal retention and “overflow” FI. An abdominal X-ray should be considered to identify colonic fecal retention if appropriate.

-

4.If fecal impaction is present, see “chronic constipation” and “refractory constipation” algorithms. If FI persists after appropriate treatment of the fecal impaction, consider further evaluation for FI as described below.

-

5,6.Patients with FI and moderate to severe diarrhea should be investigated appropriately as detailed in “chronic painless diarrhea” algorithm. If FI persists after appropriate treatment of the diarrhea, consider further evaluation for FI as continued below.

-

6.Patients with mild symptoms and/or symptoms that are not bothersome will often benefit from symptomatic management of the FI and any associated bowel disturbances, often on an as-needed basis (29). Such management may include a trial of loperamide and/or bulking agents, advice regarding the role of scheduled evacuation, and if necessary, the use of perineal protective devices. Patients with passive incontinence for a small amount of stool may benefit from a perianal cotton plug to absorb moisture and also perhaps to help with uncontrolled passage of gas.

-

8,9.If symptoms improve and there are no features to suggest an organic disorder (e.g., neurological symptoms/signs suggestive of a spinal cord lesion), further testing may not be necessary—see comment number 10). A diagnosis of FI, without qualifying whether organic or functional as defined below, may be made.

-

10.If symptoms do not improve, further diagnostic testing, in particular anorectal manometry, should be considered. The extent of such testing is tailored to the patient’s age, probable etiological factors, symptom severity, effect on quality of life, response to conservative medical management, and availability of tests. Although widely available, these tests should preferably be carried out by laboratories with requisite expertise.

-

11.The key features at anorectal manometry are anal sphincter-resting and -squeeze pressures. As anal sphincter pressures decline with age and are lower in women, the age and gender should be taken into consideration when interpreting anal pressures (30-32). The anal cough reflex is useful, in a qualitative sense, for evaluating the integrity of the lower motor neuron innervation of the external anal sphincter. It is useful to assess rectal sensation, which may be normal, increased, or decreased in FI, as these disturbances can be modulated by biofeedback therapy (27).

-

12.If these pressures are normal, a diagnosis of functional FI can be made. In addition, it is increasingly recognized that anorectal assessments may reveal disturbances of anorectal structure and/or function in patients who were hitherto considered to have an “idiopathic” or “functional” disorder. The causal relationship between structural abnormalities and anorectal function or bowel symptoms may be unclear, because such abnormalities are often observed in asymptomatic subjects (30,32). For example, up to one-third of all women have anal sphincter defects after vaginal delivery (27). As sophisticated tests (e.g., anal electromyography (EMG)) for elucidating the mechanisms of anal weakness are not widely available, the diagnosis of functional FI can also be entertained in patients, as exemplified in this case, with potentially abnormal innervation and either minor or no structural abnormalities. The Rome III diagnostic criteria for functional FI are (i) recurrent uncontrolled passage of fecal material in an individual with a developmental age of at least 4 years and one or more of the following: abnormal functioning of normally innervated and structurally intact muscles; minor abnormalities of sphincter structure and/or innervation; normal or disordered bowel habits (i.e., fecal retention or diarrhea); or psychological causes and (ii) exclusion of all of the following: abnormal innervation caused by lesion(s) within the brain (e.g., dementia), spinal cord or sacral nerve roots, or mixed lesions (e.g., multiple sclerosis), or as part of a generalized peripheral or autonomic neuropathy (e.g., diabetes); anal sphincter abnormalities associated with a multisystem disease (e.g., scleroderma); or structural or neurogenic abnormalities believed to be the major or primary cause of FI (iii) criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months.

-

13.If the sphincter pressures are abnormal, imaging of the anal sphincter should be considered. Endoanal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging are probably equivalent for imaging the internal sphincter (8,31,32). Magnetic resonance imaging is better for visualizing external sphincter and puborectalis atrophy and also visualizes pelvic floor motion in real-time without radiation exposure. Anal sphincter EMG should be considered in patients with clinically suspected neurogenic sphincter weakness, particularly if there are features suggestive of proximal (i.e., sacral root) involvement (8).

-

14.Diagnostic tests (e.g., endoanal ultrasound) may reveal disturbances of anorectal structure and/or function in patients with FI. The extent to which structural disturbances (e.g., anal sphincter defects, excessive perineal descent) can explain symptoms is often unclear (28). Therefore, the presence of structural abnormalities is not necessarily inconsistent with the diagnosis of functional FI. Many patients with anal sphincter weakness may have a pudendal neuropathy. However, it can be difficult to document a pudendal neuropathy because anal sphincter EMG requires considerable expertise and is not widely available (30,32). Therefore, patients with a pudendal neuropathy not attributable to a generalized disease process have not been excluded from the category of functional FI. A controlled study suggests that patients with FI who do not benefit from dietary modification and measures to regulate bowel habits may benefit from pelvic floor retraining (33).

-

15.The following conditions would be considered as secondary or non-functional FI: abnormal innervation caused by lesion(s) within the spinal cord or sacral nerve roots or part of a generalized peripheral or autonomic neuropathy, anal sphincter abnormalities associated with a multi-system disease (e.g. scleroderma), and structural abnormalities believed to be the major or primary cause of the FI (28).

General physical examinations, including abdominal exam, are normal. Neurological examination is grossly normal. Digital rectal examination (Box 2) does not reveal any evidence of fecal impaction (Box 3), and there are no anorectal lesions detected. There is a reduced anal-resting tone, a reduced anal-squeeze response, a normal puborectalis lift to voluntary command, and normal perineal descent during simulated evacuation (Box 2). During the digital rectal examination, perineal descent is estimated by inspecting for perineal descent during simulated evacuation and normally should be <3 cm. Perianal pinprick sensation and anal wink reflex are normal.

The gastroenterologist confirmed that she did not have episodes of loose or frequent stools (Box 5), and obtained further history that she had tried loperamide (Box 7), but this did not produce any significant improvement (Box 8) and in fact caused constipation. She had also tried using a perianal cotton plug (Box 7), but was not satisfied with this (Box 8). Anal manometry is then arranged (Box 10). This reveals average anal-resting (35 mm Hg) and -squeeze (90 mm Hg) pressures at the lower limit of normal (for her age, normal values for resting and squeeze pressure are 29–85 mm Hg and 88–179 mm Hg, respectively) (Box 11). The anal cough reflex is present but weak. Although the rectal sensory threshold for first sensation is normal, her maximum tolerable capacity is reduced (i.e., 60 cc). She is able to expel a rectal balloon within 20 s. Endoanal magnetic resonance imaging of the sphincters (Box 13) discloses mild anterior focal thinning of the internal and external sphincters (Box 14). Puborectalis structure and function appear normal. Dynamic MRI reveals normal puborectalis function during squeeze and evacuation. Based on these findings, anal sphincter weakness and altered stool consistency likely contribute to FI. As the abnormality of sphincter structure is minor, a diagnosis of functional FI is made (Box 12).

CHRONIC ANORECTAL PAIN

Case history

A 52-year-old woman is referred to a gastroenterologist because of rectal discomfort of 8 months duration (Box 1, Figure 3). She describes the pain as a deep, dull aching discomfort, lasting for some hours, and often precipitated or worsened by sitting (Box 2). The pain is not associated with bowel movements or eating (Box 4). The pain occurs inconsistently but is present, at a moderate level of severity, for as many as 4–5 days each week, and there are no pain-free intervals (Box 6). She averages five bowel movements weekly, passed with minimal straining and, on some occasions, with a sense of incomplete evacuation; there has been no change in bowel habits and no rectal bleeding. There is no history of dyspareunia, dysuria, back pain, or trauma. She has had no pelvic surgery. A pelvic exam by her gynecologist was normal and a pelvic ultrasound was negative (Box 2). A colonoscopic screening 2 years ago was normal. She has no other significant medical illnesses.

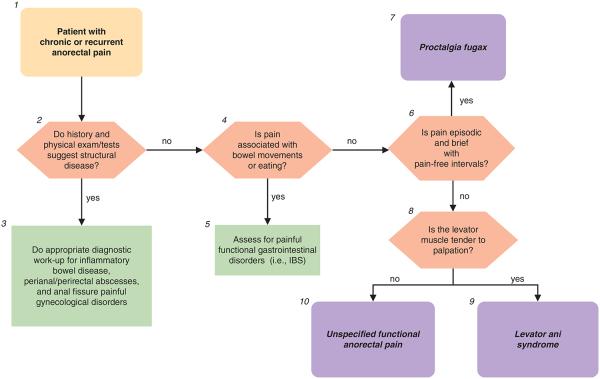

Figure 3. Chronic anorectal pain.

-

1.Pain present for at least 6 months is required for the diagnosis of functional anorectal pain syndrome. Patients with chronic anorectal pain have chronic or recurrent anorectal pain; if recurrent, pain lasts for 20 min or longer during episodes. In contrast, patients with proctalgia fugax have brief episodes of pain lasting seconds to minutes with no pain between episodes (28).

-

2–3.The history and physical exam should identify alarm and other features suggesting structural disease such as severe throbbing pain, sentinel piles, fistulous opening, and anal tenderness during digital examination, or while gently parting the posterior anus, anal strictures, or induration (34). Relevant organic causes of pain including inflammatory bowel disease, peri-anal abscesses, anal fissure, and painful gynecological conditions should be considered and identified by tests. If pain is associated with and worsened by menses, conditions that might include endometriosis, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, or other gynecological pathology should be evaluated by pelvic examination, pelvic ultrasound, and/or referral to a gynecologist. Minimal diagnostic work-up (in the absence of alarm signs) includes: CBC, ESR, biochemistry panel, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and perianal imaging with ultrasound or MRI. If there is a high index of suspicion for anal fissures, anoscopy should be considered.

-

4–5.Pain associated with bowel movements, menses or eating, excludes the diagnosis of functional anorectal pain. If pain is associated with bowel movements and leads to frequent, looser stools, or infrequent harder stools with relief upon defecation (any combination of two), then a diagnosis of IBS should be considered. See “recurrent abdominal pain and disordered bowel habit” algorithm.

-

6.An important feature of the history is whether the pain is episodic, with pain-free intervals, or not. In chronic proctalgia, pain is generally prolonged (i.e., lasts for hours), is constant or frequent, and is characteristically dull. In proctalgia fugax, the pain is brief (i.e., lasting seconds to minutes), occurs infrequently (i.e., once a month or less often), and is relatively sharp. Observation of symptom-reporting behaviors is also important. These include verbal and non-verbal expression of pain, urgent reporting of intense symptoms, minimization of a role for psychosocial contributors, requesting diagnostic studies or even exploratory surgery, focusing on complete relief of symptoms, seeking health care frequently, taking limited personal responsibility for self-management, and making requests for narcotic analgesics.

-

7.Rome III diagnostic criteria for proctalgia fugax include all of the following: (i) recurrent episodes of pain localized to the anus or lower rectum; (ii) episodes last from seconds to minutes; and (iii) there is no anorectal pain between episodes.

-

8.Rome III diagnostic criteria for chronic proctalgia include all of the following: (i) chronic or recurrent rectal pain or aching; (ii) episodes last 20 min or longer; (iii) exclusion of other causes of rectal pain such as ischemia, inflammatory bowel disease, cryptitis, intramuscular abscess, anal fissure, hemorrhoids, prostatitis, and coccygodynia; (iv) criteria fulfilled for last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. In chronic proctalgia, levator ani tenderness differentiates levator ani syndrome from unspecified functional anorectal pain. Coccygodynia is characterized by pain and point tenderness of the coccyx (9). Most patients with rectal, anal, and sacral discomfort have levator rather than coccygeal tenderness (10).

-

9.Rome III diagnostic criteria for levator ani syndrome include symptom criteria for chronic proctalgia and tenderness during posterior traction on the puborectalis muscle.

-

10.Rome III diagnostic criteria for unspecified functional anorectal pain include symptom criteria for chronic proctalgia, but no tenderness during posterior traction on the puborectalis muscle. In a patient with levator ani syndrome, anorectal manometry and rectal balloon expulsion testing should be considered. A recent study suggests that approximately 85% patients with levator ani syndrome had impaired anal relaxation during straining and approximately 85% had abnormal rectal balloon expulsion. It is unclear if dyssynergia is a cause of or secondary to pain. However, dyssynergia may guide management as discussed below. Treatment options to present to the patient can then be formulated. A randomized control trial showed that inhalation of salbutamol (a beta adrenergic agonist) was more effective than placebo for shortening the duration of episodes of proctalgia for patients in whom episodes lasted 20 min or longer (35). In a controlled study of 157 patients with levator ani syndrome, adequate relief of pain was more likely after biofeedback therapy for a concomitant evacuation disorder (87%) than electrogalvanic stimulation (EGS) (45%) or rectal digital massage (22%) (36). Biofeedback and EGS also improved pelvic floor relaxation in levator ani syndrome. In contrast, none of these measures benefited patients with functional anorectal pain. Although features of disordered defecation did not augment the utility of levator tenderness for predicting a response to biofeedback therapy, it is useful to assess defecatory functions because (i) the presence of dyssynergia before training and improvement thereof after training was very highly correlated with the success of biofeedback (and also EGS), and (ii) the biofeedback protocol is more logical to patients and providers in the presence of dyssynergia. Other treatment options include TC A or SSRI therapy or non-pharmacological therapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), hypnotherapy, or dynamic or interpersonal psychotherapy.

General physical examination, including abdominal and neurological examination, is normal. Digital rectal examination discloses no perianal disease or tenderness (Box 2). Anal canal tone and squeeze are normal. Perianal pinprick sensation and anal wink reflex are normal. Palpation of the coccyx is not painful and no masses are felt. However, there is tenderness with posterior traction of the puborectalis muscle, greater on the left than right (Box 8).

The gastroenterologist arranges a complete blood count and ESR and recommends flexible sigmoidoscopy and perianal imaging (Box 2), to exclude inflammation and neoplasia. These tests are normal. A diagnosis of levator ani syndrome is made (Box 9).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantors of the article: The Rome Foundation.

Specific author contributions: Equal contribution toward all aspects of the paper, Adil E. Bharucha and A. Wald.

Financial support: The expenses for a 1 day planning meeting were covered by The Rome Foundation and $1000 for working on the Rome algorithms.

Potential competing interests: No conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–4. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grotz RL, Pemberton JH, Talley NJ, et al. Discriminant value of psychological distress, symptom profiles, and segmental colonic dysfunction in outpatients with severe idiopathic constipation. Gut. 1994;35:798–802. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.6.798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mertz H, Naliboff B, Mayer EA. Symptoms and physiology in severe chronic constipation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:131–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrews CN, Bharucha AE. The etiology, assessment, and treatment of fecal incontinence. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;2:516–25. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leigh RJ, Turnberg LA. Faecal incontinence: the unvoiced symptom. Lancet. 1982;1:1349–51. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(82)92413-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engel AF, Kamm MA, Bartram CI, et al. Relationship of symptoms in faecal incontinence to specific sphincter abnormalities. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1995;10:152–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00298538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chiarioni G, Scattolini C, Bonfante F, et al. Liquid stool incontinence with severe urgency: anorectal function and effective biofeedback treatment. Gut. 1993;34:1576–80. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.11.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Harper CM, et al. Relationship between symptoms and disordered continence mechanisms in women with idiopathic fecal incontinence. Gut. 2005;54:546–55. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.047696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiele GH. Coccygodynia: cause and treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1963;6:422–36. doi: 10.1007/BF02633479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant SR, Salvati EP, Rubin RJ. Levator syndrome: an analysis of 316 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18:161–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02587168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tu FF, Holt JJ, Gonzales J, et al. Physical therapy evaluation of patients with chronic pelvic pain: a controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.09.002. e1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimaud JC, Bouvier M, Naudy B, et al. Manometric and radiologic investigations and biofeedback treatment of chronic idiopathic anal pain. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:690–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02050352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson RU, Orenberg EK, Chan CA, et al. Psychometric profiles and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis function in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179:956–60. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.10.084. [see comment] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pepin C, Ladabaum U. The yield of lower endoscopy in patients with constipation: survey of a university hospital, a public county hospital, and a Veterans Administration medical center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:325–32. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jameson JS, Chia YW, Kamm MA, et al. Effect of age, sex and parity on anorectal function. Br J Surg. 1994;81:1689–92. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800811143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao SS, Hatfield R, Soffer E, et al. Manometric tests of anorectal function in healthy adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:773–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diamant NE, Kamm MA, Wald A, et al. AGA technical review on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:735–60. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70195-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fox JC, Fletcher JG, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Effect of aging on anorectal and pelvic floor functions in females. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1726–35. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0657-4. [erratum appears in Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Mar;50(3):404] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao SS, Azpiroz F, Diamant N, et al. Minimum standards of anorectal manometry. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:553–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minguez M, Herreros B, Sanchiz V, et al. Predictive value of the balloon expulsion test for excluding the diagnosis of pelvic floor dyssynergia in constipation. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:57–62. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halverson AL, Orkin BA. Which physiologic tests are useful in patients with constipation? Dis Colon Rectum. 1998;41:735–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02236261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Metcalf AM, Phillips SF, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Simplified assessment of segmental colonic transit. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:40–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao SS, Kuo B, McCallum RW, et al. Investigation of Colonic and Whole Gut Transit with wireless motility capsule and radioopaque markers in constipation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasler WL, Saad RJ, Rao SS, et al. Heightened colon motor activity measured by a wireless capsule in patients with constipation: relation to colon transit and IBS. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1107–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00136.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cremonini F, Mullan BP, Camilleri M, et al. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic transit measurements for studies of experimental therapies. 35. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1781–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG, Seide B, et al. Phenotypic variation in functional disorders of defecation. Gastroenterology. 2009;128:1199–210. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bharucha A. Fecal Incontinence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1672–85. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00329-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wald A, Bharucha AE, Enck P, et al. Functional anorectal disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, editors. Rome III The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. Degnon Associates; McLean, Virginia: 2006. pp. 639–86. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wald A. Clinical practice. Fecal incontinence in adults. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1648–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp067041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diamant NE, Kamm MA, Wald A, et al. American gastroenterological association medical position statement on anorectal testing techniques. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:732–60. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bharucha AE. Update of tests of colon and rectal structure and function. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:96–103. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000196190.42296.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bharucha AE, Fletcher JG. Recent advances in assessing anorectal structure and functions. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1069–74. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heymen S, Scarlett Y, Jones K, et al. Randomized controlled trial shows biofeedback to be superior to alternative treatments for fecal incontinence. Diseas Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1730–7. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181b55455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bharucha AE, Trabuco E. Functional and chronic anorectal and pelvic pain disorders. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:685–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckardt VF, Dodt O, Kanzler G, et al. Treatment ofproctalgia fugax with salbutamol inhalation. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:686–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chiarioni G, Nardo A, Vantini I, et al. Biofeedback is superior to electrogalvanic stimulation and massage for treatment of levator ani syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.040. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]