Abstract

The lower intestine of adult mammals is densely colonized with non-pathogenic (commensal) microbes. Gut bacteria induce protective immune responses, which ensure host-microbial mutualism. The continuous presence of commensal intestinal bacteria has made it difficult to study mucosal immune dynamics. Here we report a reversible germ-free colonization system in mice that is independent of diet or antibiotic manipulation. A slow (>14 days) onset of a long-lived (t1/2>16 weeks), highly specific anti-commensal IgA response in germ-free mice was observed. Ongoing commensal exposure in colonized mice rapidly abrogated this response. Sequential doses lacked a classical prime-boost effect seen in systemic vaccination, but specific IgA induction occurred as a stepwise response to current bacterial exposure, such that the antibody repertoire matched the existing commensal content.

Immunoglobulin (Ig)A is the dominant antibody produced in mammals, mostly secreted across mucous membranes, especially in the intestine. Intestinal dendritic cells (DCs) sample small numbers of commensal bacteria at the mucosal surface and induce IgA-producing B cells through T cell-dependent and independent mechanisms (3-5). It has long been known that the IgA responses in the intestine are strongly induced by colonization of germ-free animals with commensal bacteria. The kinetics and longevity of these responses are unknown, however, because it has not been possible to uncouple IgA induction from constant bacterial exposure.

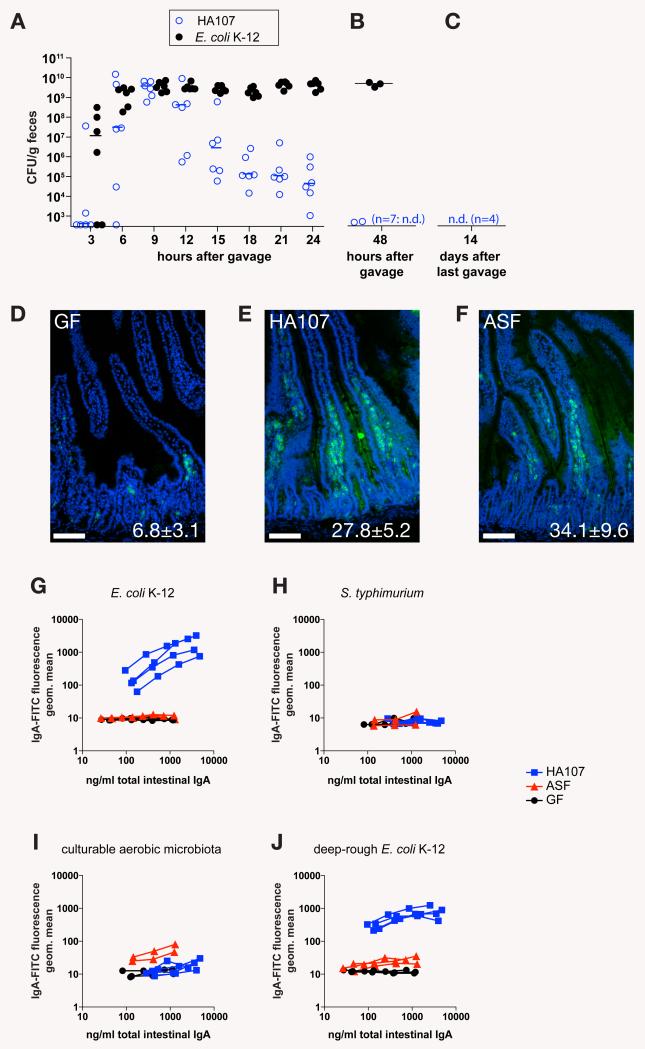

We developed a reversible in vivo germ-free colonization system by studying the persistence of auxotrophic E. coli K-12 mutants with a requirement for essential nutrients that could not be satisfied by any mammalian host metabolites (fig. S1A). Initial experiments in which germ-free mice were gavaged with an asd deletion mutant deficient in meso-diaminopimelic acid (m-DAP) biosynthesis (6) resulted in persistent intestinal colonization of some of the mice with high numbers of this strain, which could be recovered from feces and cecal contents, and grown without m-DAP supplementation. The recovered bacteria displayed gross changes in colony morphology (fig. S1B). We reasoned that under the strong selective pressure in the intestine, compensatory mutants became selected that were able to modify their peptidoglycan crosslink structure of the cell wall. To prevent this, we introduced two further auxotrophic deletions (alr, alanine racemase-1 and dadX, alanine racemase-2) to abrogate biosynthesis of the D isomer of alanine (D-Ala), which is required in the peptidoglycan crosslink, but is not a mammalian host metabolite (fig. S1A, C). This triple mutant (strain HA107) showed initial intestinal colonization identical to the wild type parental strain JM83, but the numbers of fecal live bacteria decreased 12-48 hours after gavage (Fig. 1, A and B). Even after 6 successive doses of 1010 colony forming units (CFU) of HA107, the mice all became germ-free again by 72 hours after the last dose (Fig. 1C), which demonstrated the tight control of this reversible germ-free colonization system.

Fig. 1.

Reversible E. coli HA107 colonization induces specific mucosal IgA. (A) Germ-free Swiss-Webster mice were analyzed for fecal shedding of live E. coli by bacterial plating and enrichment culture in m-DAP- and D-Ala-supplemented media of fecal material at indicated times after gavage of 1010 CFU of HA107 (n=6) or wild type parent strain JM83 (E. coli K-12; n=6). Data points represent individual mice from one experiment. Bars indicate medians. (B) Germ-free SwissWebster mice treated as in (A) with HA107 (n=9) or E. coli K-12 (n=3) and analyzed after 48h. Data from one of two independent experiments are shown. (C) Germ-free Swiss-Webster mice were gavaged 6 times over 14 days with doses of 1010 CFU of HA107, and after a further 14 days their germ-free status was confirmed by bacterial culture from feces and intestinal contents and culture-independent bacterial staining (2). n.d., not detected by enrichment culture from cecal or fecal material (<101 CFU). Data from n=4 mice from one of 7 independent experiments are shown. (D-F) Germ-free Swiss-Webster mice were gavaged 6 times over 2 weeks (1010 CFU per dose, panel E, “HA107”, n=4) or colonized with a sentinel colonized mouse containing an E. coli-free altered Schaedler flora (panel F, “ASF”, n=3) and compared to age-matched germ-free controls (panel D, “GF”, n=3). Sections of duodenum were stained with a FITC-mouse-IgA antibody (green) and DAPI (blue) as a nuclear counterstain. Insets indicate numbers of IgA plasma cells per intestinal villus (mean ± S.D.). (G-J) Live bacterial flow cytometric analysis of IgA-bacterial binding using IgA-containing intestinal washes from the mice depicted in D-F (see fig. S3 for technical details). Blue squares, HA107 gavaged mice (HA107); red triangles, ASF sentinel colonized mice (ASF); black circles, germ-free control mice (GF). Images and curves in panels D-J represent individual mice from one of 7 independent experiments.

We investigated whether E. coli HA107, which cannot divide and persist in vivo, could induce mucosal immune responses of a magnitude similar to irreversible microbial colonization. We observed an equivalent increase in numbers of intestinal IgA plasma cells throughout the intestine in germ-free mice 4 weeks after either 6 treatments with 1010 live E. coli HA107 or colonization with an altered Schaedler flora (ASF) (Fig. 1, D-F and fig. S2). We concluded that reversible germ-free colonization where animals have returned to germ-free status induces IgA immune responses that are similar to those seen with irreversible colonization. Commensal bacterial stimulation can therefore be uncoupled from the mucosal immune response in vivo.

Our reversible colonization system has a number of advantages as a way to study specific IgA induction. First, the dose of bacteria was defined and immune induction had a finite duration. Secondly, live bacteria were used in the system. Thirdly, the problems of microbiota complexity or possible bacterial overgrowth and systemic penetration during monocolonization (7) were avoided.

We investigated the specificity of the IgA response induced by E. coli HA107 as compared to wild-type E. coli or a restricted ASF microbiota using flow cytometry staining of whole bacteria ((1,2); and Fig. S3). There was a clear specific mucosal IgA response to E. coli HA107 in germ-free mice that had previously been treated with this organism (Fig. 1G), but not to Salmonella typhimurium, to which they had never been exposed (Fig. 1H). This response was similar to that seen in persistently wild type E. coli-mono-associated mice (Fig. S4). In contrast, germ-free mice colonized with an E. coli-free ASF microbiota (8) had equivalent amounts of total IgA induction (Fig. 1I), but no specific E. coli binding (Fig. 1G). LPS O-antigen and core polysaccharides can mask bacterial surface proteins, and thereby define bacterial antibody binding to a large degree (9). Bacterial pre-absorption analysis of HA107-induced IgA showed that the LPS core antigen of E. coli K-12 was not a dominant IgA epitope, but could partially shield other surface epitopes that became accessible on a “deep-rough” E. coli ΔrfaC mutant that expresses a truncated core antigen (Fig. S5). Since shielding was only partial, flow cytometry of deep-rough E. coli gave very similar results as wild-type E. coli K-12 (Fig. 1J). This indicates induction of a highly specific IgA response to live bacterial antigen, rather than expansion of a natural polyclonal or oligoclonal response by stochastic class switch recombination of random natural specificities.

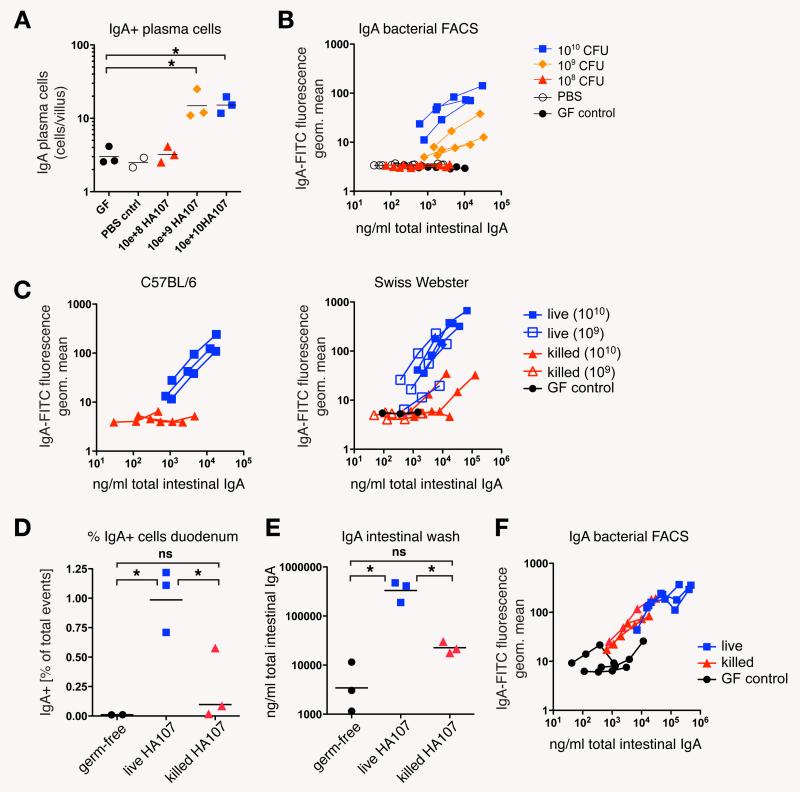

We were able to address the dose of live bacteria required for IgA induction because our reversible system used live but non-replicating bacteria. We found that in germ-free mice there was no measurable IgA response if we gavaged mice with doses below 109 HA107 CFU (Fig. 2, A and B). Bacteria killed by heat treatment (Fig. 2C) or peracidic acid fixation (Fig. 2, D-F) were ineffective at inducing the response. Similar high bacterial thresholds for mucosal IgA induction were observed previously in conventional mice treated with live wild type bacteria (3). Early translocation of live bacteria to the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) in germ-free C57BL/6 mice is similar to germ-free JH−/− mice (Table S1), suggesting that preformed “natural” IgA which does not bind commensal bacteria (Fig. 1, G, I, and J) does not contribute to this threshold. This strongly suggests that the high threshold for IgA induction is not attributable to competition with endogenous bacteria or their breakdown molecules. Assuming that the intestinal barrier during repeated transient colonization is representative of colonized animals, the high threshold is an intrinsic property of the mucosal bacterial sampling system, which appears to sample only a tiny fraction of the live bacteria present (3), in order to mount a protective mucosal immune response without the risk of mucosal or systemic infection.

Fig. 2.

Germ-free mice require a large dose of live bacteria for IgA production. (A) Germ-free Swiss-Webster mice were gavaged 6 times over 14 days with the indicated amounts of HA107 or PBS vehicle control only, or kept as germ-free controls (GF control), and analyzed at day 14. Tissue sections were stained for mouse-IgA to determine the numbers of duodenal IgA plasma cells. (B) Live bacterial flow cytometric analysis of intestinal washes from the mice described in (A) Data points and curves in A and B represent individual mice from one of two experiments. (C) Doses of 109 or 1010 CFU of either live or heat-killed (15 min autoclaving) HA107 were gavaged into germ-free C57BL/6 and Swiss-Webster mice (6 times over 2 weeks) and analyzed by live bacterial flow cytometry on day 14. Black circles, germ-free control kept in the same isolator. Curves represent individual mice from one experiment. (D-F) Doses of 1010 CFU of live or peracidic acid-killed HA107 were gavaged into germ-free Swiss-Webster mice (6 times over 2 weeks) and analyzed by flow cytometric analysis of duodenal leukocytes (D), IgA-specific ELISA (E) and live bacterial flow cytometry (F) on day 14. Germ-free controls are depicted as black circles. Data points and curves represent individual mice from one experiment. Horizontal bars indicate means; *, statistically significant (p<0.05; 1-way ANOVA); ns, non-significant.

Immune memory conferring lifelong immunity to infections such as measles can be mediated by neutralizing antibody against systemic pathogens (10). Persistence of the immune response and larger, more rapid subsequent responses are a key part of the success of many vaccines and responses to pathogens in vivo (11). Primary systemic immune responses normally result in low IgM antibody titers and the establishment of a memory cell population, which generates a rapid increase in antibody producing cells and high affinity antibody production upon subsequent challenge. This synergistic effect of repeated immunizations normally increases with the interval length between sequential doses (12). Furthermore, memory serum antibody responses may also benefit from non-specific stimulation, such as commensal bacterial products (13), but it is unclear whether this could apply to specific responses in the mucosal immune system.

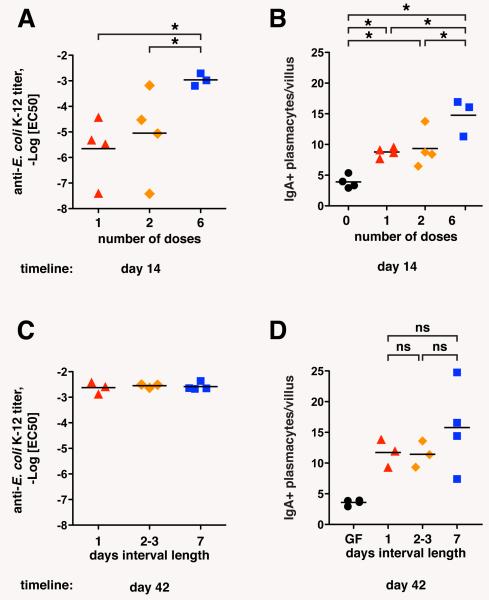

The persistent nature of intestinal bacterial colonization has made it previously impossible to study immunological memory in the context of intestinal anti-microbiota IgA production. Reversible bacterial colonization, however, allowed us to immunize orally with defined pulses of live bacteria, and measure the effects of single and sequential immunizations, and later persistence or loss of the response. The IgA response increased in an additive fashion with the number of bacterial doses (1, 2 or 6 doses of 1010 CFU, spread over 7 days and measured after 14 days; Fig. 3, A and B; fig. S6, A and B), but 6 repetitive bacterial doses of 1010 CFU generated equivalent IgA responses independent of the dose interval length (24 hours, 2-3 days, or 7 days; Fig. 3, C and D; fig. S6, C and D). Even in the extreme case where a dose of 3×1010 HA107 was given within 24 hours, or spread out as 3 equally spaced sequential doses of 1×1010 CFU over 2 weeks (a 7 day interval) the secretory IgA and the response to deep-rough bacterial surface antigens was equivalent (fig. S7, A, C and E), although there was a small increase in the plasma cell number and the response to wild type E. coli K-12 (Fig. S7, B, D and F). We therefore conclude that the commensal-specific IgA response does not show synergistic but mainly additive effects of sequential immunizations regardless of dose interval, in contrast to the paradigm of systemic immune memory.

Fig. 3.

Additive induction of intestinal IgA in proportion to bacterial exposure. Germ-free C57BL/6 mice were (A, B) given 1, 2 or 6 doses of 1010 CFU HA107 over the course of 1 week and analyzed at day 14. (C, D) In parallel, 3 groups of mice were given 6 doses in intervals of 1, 2-3 or 7 days apart, and analyzed on day 42. Intestinal washes were analyzed by IgA specific ELISA and live bacterial flow cytometry. -LogEC50 values of IgA-E. coli binding were calculated as described in Materials and Methods (2; A, B), and numbers of duodenal IgA plasma cells were determined from 7 μm frozen sections stained for mouse IgA (C, D). Bars indicate means; *, statistically significant p<0.05 (1-way ANOVA); ns, non-significant. Data points represent individual mice from one of two experiments.

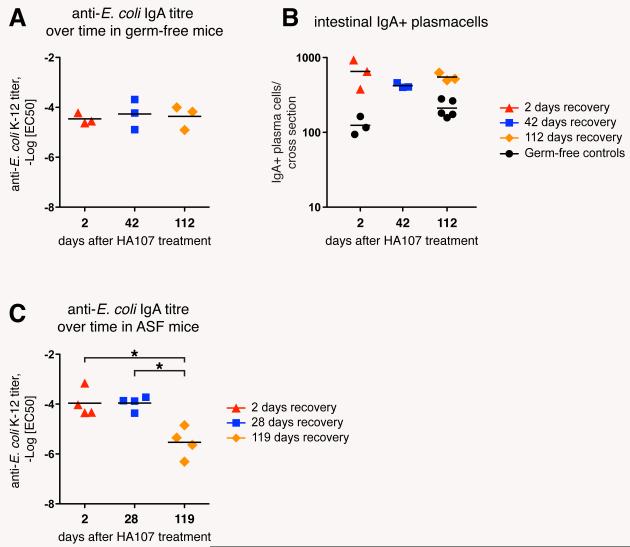

The integration of specific bacterial numbers over time into bacterial-specific IgA titers could serve to adjust the intestinal IgA repertoire to gradually changing microbiota composition. The persistence of specific antibody titers can also be used to assess immunological memory. We therefore determined IgA persistence following reversible HA107 colonization. The longevity of microbiota-induced intestinal IgA plasma cells of conventional mice has been determined previously with an average half-life of 5 days and a maximum life time of 6-8 weeks (14), although this contrasts with measurements of a very long lifespan of some plasma cells (≥1year) in the bone marrow (15, 16). We found no measurable decrease in the specific IgA responses in HA107-treated mice 16 weeks after exposure (Fig. 4, A and B; fig. S8A), despite the frequencies of MLN and Peyer’s patch GL-7+ germinal center B-cells returning to germ-free levels within 2-6 weeks (Fig. S9). Short-lived induction of germinal centers and persistent intestinal IgA plasma cells would be consistent with very long plasma cell half-lives as previously measured in the bone marrow, and although there is no evidence of live bacterial long-term persistence in lymphoid organs (Fig. S10) and IgA heavy chain sequences show N-nucleotide insertion but very limited hypermutation (Table S2), there may still be low amounts of ongoing B cell activation through commensal antigen retention in immune complexes or by follicular or conventional DCs. Pre-existing or induced CD4 T cells may also contribute to IgA induction dynamics (17). Our data, however, suggested that once the IgA response was induced in mice that have returned to germ-free status, the specific repertoire is effectively altered only by restimulation with new bacterial species.

Fig. 4.

Commensal-induced specific IgA is long-lived in germ-free mice, but rapidly lost in the face of ongoing IgA induction in microbiota-colonized mice. (A) Germ-free Swiss-Webster mice were gavaged 6 times over 2 weeks with 1010 CFU HA107 and kept germ-free for up to 112 days after discontinuation of HA107 treatment. Intestinal washes taken at the indicated time points were analyzed by IgA specific ELISA and live bacterial flow cytometry, and -LogEC50 values of IgA-E. coli binding were calculated. (B) Tissue sections from the experimental mice described in (A) were stained for mouse IgA to determine the numbers of IgA plasma cells in HA107-treated and germ-free control mice. (C) Colonized mice containing an E. coli-free ASF microbiota were treated as described in (A) and kept under barrier conditions for up to 119 days after discontinuation of HA107 treatment, and analyzed as above at the indicated time points. Bars indicate means; *, statistically significant (p<0.05; 1-way ANOVA). Data points in A and B, respectively in C represent individual mice from one of two independent experiments.

To test whether there is attrition of specific IgA production in the lamina propria of animals colonized with a commensal bacterial flora, we gavaged ASF mice with HA107. This resulted in a similar HA107 response to that seen in germ-free animals after 2 weeks, but now the response was attenuated within <17 weeks of discontinuing the intestinal HA107 immunization (Fig. 4C; fig. S8B). Similar attrition of the specific IgA response induced by HA107 in germ-free mice was seen when they were subsequently treated with commensal species Enterococus faecalis, Enterobacter cloacae, and Staphylococcus xylosus (Fig. S11). This suggests that in colonized animals persistence of a specific IgA response is limited by restimulation with other commensal bacterial species, allowing the mucosal immune system to adapt its IgA to commensals that are currently present in the intestine.

Using this system to allow transient colonization of germ-free mice in the absence of any other manipulation, we described that, (i), induction of high titer IgA can be uncoupled from permanent intestinal bacterial colonization, (ii), that an intrinsic threshold exists between 108 and 109 bacteria below which the intestinal IgA system does not respond, (iii), that the intestinal IgA system lacks classical immune memory characteristics, and (iv), that the intestinal IgA repertoire is characterized by constant attrition, and thus represents the dominant species currently present in the intestine. This deviates significantly from classical systemic immune memory paradigms, and impacts on mucosal vaccine design and harnessing the effects of probiotic bacteria. Teleologically, intestinal IgA and serum IgG systems can be seen as complimentary systems, with the intestinal IgA system continuously adapting to and protecting from the current microbiota, and the systemic IgG system being capable of rapid and highly specific responses to previously encountered invasive pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Zhang, H. Roberts, J. Notarangelo, S. Armstrong, S. Competente, M. Provenza, J. Bodewes, and R. McArthur for their technical support; B. Stecher, W.-D. Hardt, A. J. Müller, N. A. Bos, C. Mueller, R. M. Zinkernagel, A. G. Rolink, A. Lanzavecchia, and C. Reis e Sousa for their helpful comments and editing the manuscript. Grant support: Swiss National Science Foundation (310030_124732), Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation of Canada, Genome Canada, Farncombe Foundation, Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. This research was also supported with funding from the Canada Research Chairs program to K.D.M. and A.J.M,. M. H. is a fellow of the Prof. Dr. Max Cloëtta foundation and was supported by grants of the Oncosuisse foundation (OCS 02113-08-2007). S.H. was supported in part by a German Science Foundation fellowship, and the clean mouse facility Bern was supported by the Genaxen Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare.

References and Notes

- 1.Slack E, et al. Innate and adaptive immunity cooperate flexibly to maintain host microbiota mutualism. Science. 2009 Jul 31;325:617. doi: 10.1126/science.1172747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 3.Macpherson AJ, Uhr T. Induction of protective IgA by intestinal dendritic cells carrying commensal bacteria. Science. 2004 Mar 16;303:1662. doi: 10.1126/science.1091334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macpherson AJ, et al. A primitive T cell-independent mechanism of intestinal mucosal IgA responses to commensal bacteria. Science. 2000 Jun 23;288(9):2222. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5474.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McNulty Peterson, Gordon Guruge. IgA Response to Symbiotic Bacteria as a Mediator of Gut Homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe. 2007 Nov 15;2:328. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakayama K, Kelly SM, Curtiss R. Construction of an ASD+ Expression- 13 Cloning Vector: Stable Maintenance and High Level Expression of Cloned Genes in a Salmonella Vaccine Strain. Nature Biotechnology. 1988 Jun 1;6:693. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shroff KE, Meslin K, Cebra JJ. Commensal enteric bacteria engender a self-limiting humoral mucosal immune response while permanently colonizing the gut. Infect Immun. 1995 Oct 1;63:3904. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3904-3913.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stecher B, et al. Like will to like: abundances of closely related species can predict susceptibility to intestinal colonization by pathogenic and commensal bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2010 Jan 1;6:e1000711. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bentley AT, Klebba PE. Effect of lipopolysaccharide structure on reactivity of antiporin monoclonal antibodies with the bacterial cell surface. J. Bacteriol. 1988 Mar 1;170:1063. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1063-1068.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zinkernagel RM, Hengartner H. Protective ‘immunity’ by pre-existent neutralizing antibody titers and preactivated T cells but not by so-called ‘immunological memory’. Immunol Rev. 2006 Jun 1;211:310. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tough DF. Deciphering the relationship between central and effector memory CD8+ T cells. Trends Immunol. 2003 Aug 1;24:404. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fecsik AI, Butler W, Coons AH. Studies on antibody production. XI. Variation in the secondary response as a function of the length of the interval between two antigen stimuli. J. Exp. Med. 1964 Dec 1;120:1041. doi: 10.1084/jem.120.6.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernasconi NL, Traggiai E, Lanzavecchia A. Maintenance of serological memory by polyclonal activation of human memory B cells. Science. 2002 Dec 13;298:2199. doi: 10.1126/science.1076071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattioli CA, Tomasi TB. The life span of IgA plasma cells from the mouse intestine. J. Exp. Med. 1973 Aug 1;138:452. doi: 10.1084/jem.138.2.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manz RA, Thiel A, Radbruch A. Lifetime of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nature. 1997 Jul 10;388:133. doi: 10.1038/40540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slifka MK, Antia R, Whitmire JK, Ahmed R. Humoral immunity due to long lived plasma cells. Immunity. 1998 Mar 1;8:363. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cong Y, Feng T, Fujihashi K, Schoeb TR, Elson CO. A dominant, coordinated T regulatory cell-IgA response to the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009 Nov 17;106:19256. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812681106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.