Abstract

Background

Understanding how low-income, uninsured African American/black men use faith to cope with prostate cancer provides a foundation for the design of culturally appropriate interventions to assist underserved men cope with the disease and its treatment. Previous studies have shown spirituality to be a factor related to health and quality of life, but the process by which faith, as a promoter of action, supports coping merits exploration.

Objective

Our purpose was to describe the use of faith by low-income, uninsured African American/black men in coping with prostate cancer and its treatment and adverse effects.

Methods

We analyzed data from a qualitative study that used in-depth individual interviews involving 18 African American men ranging in ages from 53 to 81 years. Our analysis used grounded theory techniques.

Results

Faith was used by African American men to overcome fear and shock engendered by their initial perceptions of cancer. Faith was placed in God, health care providers, self, and family. Men came to see their prostate cancer experience a new beginning that was achieved through purposeful acceptance or resignation.

Conclusions

Faith was a motivator of and source for action. Faith empowered men to be active participants in their treatment and incorporate treatment outcomes into their lives meaningfully.

Implication

By understanding faith as a source of empowerment for active participation in care, oncology nurses can use men's faith to facilitate reframing of cancer perceptions and to acknowledge the role of men's higher being as part of the team. Studies are needed to determine if this model is relevant across various beliefs and cultures.

Keywords: African American/black, Faith, Prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed non-cutaneous malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer death among American men.1,2 African American men bear a disproportionate burden of prostate cancer with higher incident and mortality rates.1 Additionally, treatments for prostate cancer may cause temporary or long-term adverse effects, such as erectile dysfunction (ED), urinary incontinence, fatigue, depression, and hot flashes. Incorporating the disease, its treatments, and outcomes is a complex, multifaceted process for men, which can impact their quality of life.

Studies have shown that one's spirituality can be a coping mechanism when dealing with life-threatening diseases, its management, and its symptoms.3–7 Spirituality is defined as “the personal quest for understanding answers about life, about meaning, and about relationship to the sacred or transcendent, which may (or may not) lead to or arise from the development of religious rituals and the formation of community.”8 Throughout African American history, spirituality has played a prominent role in dealing with adversity, such as serious illness, and providing hope and group identity through religious institutions.9–13 In the health care context, higher scores on measures of spirituality have been associated with better management of chronic illness, higher levels of health promoting activities, and better health-related quality of life (HRQOL).3,14–16 Faith is considered to be a manifestation of spirituality and is defined in the religious context as “a congruence of belief, trust, and obedience in relation to God or the divine.”17 However, in the health care context, faith can also be placed in health care providers, family, self, and others,17 such that there is a congruence of belief, trust, and obedience in relation to these entities. It is this broader sense of faith that emerged in this analysis.

Background

Few studies consider spirituality among men with prostate cancer. Krupski and colleagues18 found that the psychosocial domains of general HRQOL and specific domains of prostate-specific quality of life were negatively associated with low spirituality among low-income, uninsured, ethnically diverse men treated for prostate cancer. In a second study, sampling from the same population, investigators found that the meaning/peace subscale of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapies–Spiritual Well-being was a major contributor to the positive association between spirituality and HRQOL.19 Furthermore, these investigators found that, in the absence of high meaning/peace scores, higher faith scores were negatively associated with HRQOL.19 Finally, in a grounded theory study of spirituality among men with prostate cancer, investigators found that spirituality was integral to men's coping with their cancer at all phases of the trajectory—from facing cancer to choosing treatment to trusting and living day by day.4 Whereas the men in the first 2 studies were from the same ethnically diverse population as the current study, the men in the third study were all English speaking, with interviews occurring in the hospital during recovery from surgery. Information on participants' socioeconomic status and ethnicity were not provided; thus, little is available in the literature to address specifically how low-income, uninsured African American men may use spirituality or faith to cope with prostate cancer, its treatment, and adverse effects.

The purpose of the initial study, of which this is a substudy, was to explore the meaning of prostate cancer treatment–related symptoms among low-income African American and Latino men. As described by Maliski and colleagues,20 men underwent a process of renegotiated masculine identity as they integrated symptoms such as ED and incontinence into their lives. However, the data clearly showed that faith was significant to a man's ability to cope with the life-altering adverse effects of treatment and the progress of his recovery. We, therefore, reanalyzed the transcripts of 18 of the African American/black men who participated in the initial study, focusing on the role of faith in coping with their prostate cancer diagnosis, treatment, and adverse effects.

Methods

We used a qualitative approach to capture cultural meanings at the interface between the health care system for the uninsured and the cultural backgrounds of the men using this system. We used grounded theory techniques to develop a descriptive model based on meanings that emerged from the data with regard to the role of faith within the context of having symptoms related to prostate cancer treatment.21

Participants and Setting

For the initial study, we recruited men who self-reported their race as African American/black from 4 sources throughout California: (1) IMPACT (Improving Access, Counseling, and Treatment for Californians with prostate cancer), a state-funded program that provides free prostate cancer treatment and nurse case management to uninsured and underinsured, low-income men; (2) a local Veterans Administration Medical Center urology clinic; (3) advertisements placed in local newspapers targeting African American/black communities; and (4) mailings to local prostate cancer support groups. We enrolled 18 men from IMPACT, 6 men from the Veterans Administration Medical Center, and 11 men through newspaper advertisements and support group mailings. All men recruited into the study had incomes less than 300% of the Federal Poverty Level. This analysis focused on 18 of the 35 African American/black men enrolled in the initial study. These men were selected because all were from the IMPACT program and therefore had similar access to treatment and nursing symptom management support. Men recruited from other settings did not have the same nursing support. All study protocols were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Office for the Protection of Research Subjects and were compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (Table).

Table.

Participant Demographics

| Participant | Age, y | Education | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 002 | 70 | HS+ | RT |

| HT | |||

| 005 | 69 | HS | RT |

| 007 | 64 | PhD | RT |

| HT | |||

| Chemo | |||

| 012 | 76 | <HS | Brachy |

| 014 | 70 | BS | HT |

| 018 | 76 | HS+ | RRP |

| 034 | 81 | BA | RRP |

| RT | |||

| HT | |||

| 260 | 52 | 10th grade | RRP |

| HT | |||

| 393 | 67 | Technical school (Jamaica) | RT |

| HT | |||

| 472 | 60 | HS | RRP |

| 502 | 64 | BA | HT |

| 543 | 58 | HS+ | RRP |

| RT | |||

| 768 | 56 | HS+ | RRP |

| 902 | 53 | HS | RRP |

| 905 | 56 | HS | RRP |

| 1000 | 64 | HS+ 3 | RT |

| 1147 | 69 | AA | RRP |

| 1157 | 53 | 11th grade | RT |

Abbreviations: AA, associate's degree; Brachy, brachytherapy; BS/BA, bachelor's degree; Chemo, chemorherapy; HS, high school; HT, hormone therapy; RRP, radical prostatectomy; RT, radiation therapy.

All men in this sample spoke English. Ages ranged from 53 to 81 years. All but one of the men was born in the United States. Men reported a range of formal education, from less than high school to having a doctorate. At the time of interview, treatments ranged from monotherapy with surgery, hormone ablation, or radiation to multiple modalities. For most, additional treatment was in response to biochemical recurrence following primary treatment with either radiation or surgery. We did not collect data on the effects of primary treatment for these men other than as discussed in the interviews. All men perceived themselves to be experiencing or having experienced ED and/or incontinence, which was the focus of the initial study.

Data Collection

After providing written informed consent, men were scheduled for their baseline interview. They were given a choice of having the interview in person either at UCLA in a private room, in their home, or by telephone. Telephone was the only option for those living more than 50 miles from UCLA. We saw no evidence of differences in information shared between those interviewed in person versus those interviewed by telephone. The major limitation with telephone interviews was the absence of visual observation. However, interviewers completed a debriefing form following each interview on which they noted their impressions of body language and environment for in person interviews and voice tone and background noise for telephone interviews. An ethnicity-concordant, trained male interviewer using a semistructured interview guide conducted all interviews. The interviews lasted 1 to 2 hours, and participants were asked to talk about their treatment and related symptom experiences from their diagnosis of prostate cancer, through treatment, to the present. All men were diagnosed and treated for early-stage prostate cancer. At the time of the interviews, 6 men were being treated for recurrent disease and 1 man was receiving chemotherapy for hormone-refractory disease. Although men were not asked about religious affiliation, practices, or spirituality, references to faith arose spontaneously throughout the interviews. The interview guides used open-ended topical prompts and probes to gain the desired depth of information about managing treatment-related symptoms. Men were contacted for second interviews 3 to 6 months following the initial interview to clarify or expand on concepts identified in their baseline interviews or to confirm emerging themes. Because of the emergent themes related to spirituality and faith, questions related to the role of spirituality and faith in coping with their prostate cancer were added to the follow-up interviews. Examples include: “Do you feel your relationship with God or your sense of spirituality has changed after prostate cancer, and if so, can you tell me how or do you feel it?” and “What role does spirituality or God play for you in your prostate cancer experience?” All interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

The method for this study drew on grounded theory techniques to develop a descriptive model of the role of spirituality and faith within the context of prostate cancer treatment–related incontinence and/or ED.21 Analysis was undertaken by the first author in collaboration with the project manager and African American research assistant who participated in all steps of the analysis process. Transcripts were read in their entirety followed by close line-by-line coding. Each line was read and coded for the major thought or idea expressed. As new codes were expressed, they were compared with previous codes. As coding and comparison continued, common characteristics began to emerge, which were then sorted into categories. We then returned to the data with questions about the categories to describe them further in terms of properties and dimensions. Follow-up interviews were used to explore categories in which there were gaps in description or understanding. Concurrently with this process, relational statements were suggested and explored in the data relative to the dimensions and properties within and between categories and subcategories. After relationships were confirmed by the team, as supported by the data, a model was developed to describe the role of spirituality and faith as it emerged from the data. The first author and the 2 study staff members independently carried out this interpretive process. Categories and relationships were confirmed by returning to the transcripts and in follow-up interviews. Throughout the analytic process, memos were written on codes and categories as they were developed, decisions about categorization, descriptions of the categories, theoretical hunches and questions, and decisions made about relationships and the model.

Results

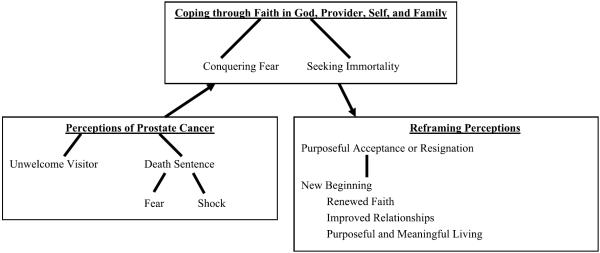

The analysis revealed that faith was a major resource for African American/black men, helping them move from a perception of cancer as a death sentence to the integration of their cancer into their lives. Personal stories revealed that these men derived strength from their relationship with God and that faith empowered them to collaborate with their health care professionals (Figure).

Figure.

Faith and coping with prostate cancer.

Initial Perceptions of and Responses to the Prostate Cancer Diagnosis

Men's first perception of and responses to their diagnosis of prostate cancer were complex and dynamic. The first reaction to the cancer diagnosis was that it was a “death sentence” and was accompanied by fear and shock. Interwoven with this were concerns for their family as well as resentment of the cancer as an “uninvited visitor.” However, by using faith, these initial perceptions eventually were modified.

FACING A DEATH SENTENCE

For all men interviewed, the diagnosis was characterized as a “death sentence.” Men expressed that dying was no longer seen as something far in the future, but something that could happen very soon, now that they had cancer. Death was now personal and very near. As 2 of the men expressed:

When I first heard about it, I said, oh everything is over.

I thought that, uh, prostate cancer was like, I was goin' to die.

All but 2 of the men in “facing a death sentence” expressed fear. The focus of their fear was the uncertainty that their cancer diagnosis brought to their lives. This uncertainty re-sulted in a considerable amount of distress as they reacted to their diagnosis and believed it to be a death sentence. The perception of imminent death brought a number of fears to the forefront, including the fear of dying, not being cured, and leaving their families, to treatment, pain, and the unknown. Foremost in their thoughts was worry about their families. Men expressed concern about what would happen to their families if they should die. Not only was their future in jeopardy, but so was the future of their families.

Shock was another response expressed by 16 of the men to their prostate cancer diagnosis. These men indicated that they were shocked and surprised when they learned of their diagnosis. As a man stated, “I was totally in shock…. I was thinking how something else how in the world… cancer.” Even 2 men, who had a family history of prostate cancer, were stunned by their diagnosis. One man expressed it as, “(I was) very surprised, you know, even though prostate cancer runs in my family… my grandfather and 2 uncles passed from prostate [cancer].” Another stated, “When, I was first told that I had it, I was completely knocked off my feet because I had no indications of anything being wrong.” Conversely, 2 men took their diagnosis in stride because they expected that it was inevitable. They were not shocked because they recognized that their family history and race increased their risk of being diagnosed as exemplified below:

Not really surprised…. It was just like I go to the doctor, and he says you have the flu. That's kind of how I did look at it.

I had learned something about prostate cancer and realized the possibility that anybody can get it so… and realized over a number of treatments, so I was never really upset about it.

And at my age was the point where… most of the African men, discover to have it.

AN UNWELCOME VISITOR

Cancer was also perceived by some men as “a visitor in their bodies.” It was seen as a deadly intruder, but one that was not owned by the men and was, hopefully, temporary. For these men, cancer came from the outside. One participant captured this when he said, “To me, cancer was always a visitor that visited my body. God didn't leave me with the cancer because he is visiting me, the time He decides that… to die on, and said [to cancer] get out of here, you're [cancer] not gonna win here.” This man expressed clearly that God is the one who determines when one dies, not the cancer, because it is just a visitor. Nonetheless, this visitor brought the specter of death, which was resented.

Faith as a Coping Resource

All of the men's stories revealed that faith was used to conquer multiple fears associated with their diagnosis, treatment, management of adverse effects, and their heightened sense of their own mortality.

CONQUERING FEAR

Men freed themselves from their fear of facing their cancer, treatment, and possible death by using faith. Men believed their diagnosis was fate or God's will. Their health was in God's hands, so they did not have to worry or be fearful:

As long as my heart and spirit are good, I can keep going. Good things can happen in the future, and I was put on Earth for a reason so I'm not afraid of death.

Furthermore, some men had no fear of dying, because they felt that God had determined their time to die. They did not fear death because their faith instilled in them a belief in God's will and the promise of an afterlife.

Despite their use of faith to cope with the threat of death, 3 men were still worried about being in pain. Although faith did not keep them from fearing pain, it did provide them with the strength to undergo their treatment and to handle any adverse effects that occurred. This was often expressed as follows: “I prayed, and God gave me the strength I needed” or “The prayers of everyone got me through this.” Strength was received through faith and the actions of praying for oneself or others praying for one's health. Faith as expressed by these men was not limited to faith in God, but also in health care providers, self, and others, especially family.

FAITH IN GOD

Some men reported having a renewal of faith in response to their diagnosis. This allowed them to cope with and view their diagnosis positively. Conversely, a response expressed by another man was “running away” from his faith and then returning to it as his treatment progressed. Seventeen of the men voiced actively seeking out their faith and expressed new enjoyment in their revitalized faith and a sense of meaning and connectedness that came with it. “And it really put me in touch with where do I go from here and what I have done with my life, and I guess is sort like the thief on the cross: one thief been crucified, and you know he says you know I want to confess. I wanna be with you in paradise so, and he confessed, and it wasn't too late so maybe it wasn't too late for me either.” Indeed, as this quote illustrates, men hoped that there was a “paradise” and that by turning back to faith, they would be part of that afterlife.

Bargaining with God was another means of coping with their prostate cancer related to their faith. Men bargained with God in the belief that He had the power to alter their fate. In exchange for more years of life, men vowed to perform God's works, such as “becoming more involved in the church,” “setting a better example for men in the neighborhood,” or “educating other men about prostate cancer.” Again, they expressed faith that God could do this, if it was His will.

FAITH IN FAMILY

When men had family members who were successfully treated for prostate cancer, they had faith that they also could be successfully treated. “And he just passed maybe, ah, 6 month ago; he was 95. So… it kinda helped me out a little bit you know.” Another man stated, “When I first heard about it, I said, oh, everything is over, and when I told my dad, he said that he had it so you know that gave me a little you know a little ah… you know ah hope you know.” All of the men attributed the strength to cope with prostate cancer and its treatment to the support received from family members and the faith exhibited in their continuing presence.

FAITH IN HEALTH CAREGIVERS

Men's physicians played a major role in their prostate cancer treatment experience. As the men related their stories, their physicians were imbued with a spiritual quality. The men believed that God had given them the skill to cure their cancer. Physicians were seen as God's instrument or “angels of mercy.” Men expressed having “faith” in their surgeon that he would be able to rid them of their cancer. However, although they viewed their doctors as skilled at their job in healing the body, the ultimate creator and controller of the body was God. As one man put it, “let the doctors do their job, but God made the body.” Conversely, 2 of the men expressed the belief that their doctors, leading them to choose the wrong treatment, misinformed them or that they were not taken seriously because of their race and/or socioeconomic status representing a breach of faith.

FAITH IN SELF

Men talked about having to “do their part” as well to overcome their prostate cancer. Placing their faith in God or their physicians did not absolve them from their responsibility in recovering from their prostate cancer. Through faith in themselves, men believed that they had the strength to do their part in dealing with their prostate cancer. God had his role, the physician had his/her role, and the patient had a role to play in a successful treatment and recovery.

SEEKING IMMORTALITY

Once diagnosed with prostate cancer, men had a heightened sense of their own mortality. They sought to conquer this fear by ensuring that they would maintain a presence in the world if they died. Searching for immortality was a common coping response expressed by the men. Men saw their faith as a means to immortality. They discussed their future in terms of life expectancy and an afterlife. Men's belief in an afterlife was of 2 camps—the first group strongly believed in an afterlife, which would be a “paradise,” whereas the others were uncertain as to how, where, or if they would live on if prostate cancer ended their physical life.

The men expressed wanting to ensure that their families would be able to continue when they were not there. This was another expression of their desire for immortality through their families. For some men, this would be achieved by arranging their finances and insurance so that their families would not be left destitute. As one man stated, “Then I realized that I have to, uh, get things set up financially over the year I have, and I want her to be set up. I don't wanna leave bankrupt and all other stuff so a lot of things that go through your mind when you hear something like this.”

Men expressed that they could not fathom that they would not be part of the world in the future. Their accomplishments, successes, possessions, family members, and friends would all disappear. They expressed concern that their memories, legacy, and impact on the world might also die. This was presented as a very painful aspect of contemplating mortality for some of the men. “It's final so, without life, all of the other things that you may wanna be concerned they don't even exist because death it's final. My brain was not to have the death part.” Leaving a legacy through completion of responsibilities was a way of achieving immortality for some of the men.

Reframing Perceptions

As men progressed through the treatment and posttreatment, their stories revealed that they came to reframe their perceptions of their prostate cancer with the support of their faith. A majority of men spoke of their cancer as giving them a “new beginning” with reprioritized values and appreciation for life. Sixteen of the men used purposeful acceptance to achieve this, although resignation was seen in 2 of the men.

A NEW BEGINNING

Some men saw their diagnosis as a new beginning. Because cancer threatened their lives, they talked of a desire to make the most of their lives, to extend their lives as much as possible, and to have a more fulfilling life. Their diagnosis was seen as an impetus for reprioritizing values and adding meaning to life through improving relationships, renewing faith, and focusing on purposeful and meaningful living.

IMPROVED RELATIONSHIPS

Participants talked of focusing more on making loved ones and themselves happy and improving their relationships. One man stated that he saw himself as his family's spiritual leader and responsible for serving as a role model as he dealt with his adversity. He had a new mission in life:

I'm the spiritual leader of this family… then I'm someone that my daughters and my grandchildren… they look at me as their role model and I wanna be the role model. I don't wanna let this drown me down so much, I want them to see me, uh, that I fight this whether the battle will be medical or economical, I want to fight it, it means that God designated me to fulfill these roles.

RENEWED FAITH

Some men viewed their diagnosis as God's way of reinforcing their waning faith. For others, it was a gift that forced them to reassess what was important in their lives. One man, who felt separated from God, said the cancer diagnosis and awareness of his own mortality presented him with a path back into a renewed spiritual relationship and a new, more enriched life:

I thought I was going to die from the pain and was ready to die, and I didn't have faith, but I surrendered to it and realized it wasn't my time to die. I thought God has me here for a reason, so I'm back with God and talking to men about getting PSA tests. I want to give a talk at a large church about how important it is to get screened and what happened to me.

Men talked about becoming more spiritual, prayerful, and more active in their churches since their diagnosis. One man stated that he had even become a deacon in his church. These men were upholding their end of their bargains with God.

PURPOSEFUL AND MEANINGFUL LIVING

Men also talked of revising their attitudes toward prostate cancer through this renewed sense of faith. When diagnosed, men personified cancer as an unwelcome visitor in their bodies and the representation of death, but now men talked of positive aspects of their treatment experience. Some found a new purpose in sharing their prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment experiences to encourage other men to be screened for prostate cancer. As one man stated: “A positive that came from my cancer is that, ah, I talk to others about getting the test.” The participants stated that they now realized it was possible to be healthy and productive and have a positive attitude while having cancer. The strength for this was attributed to faith in God, in their health care providers, in the support of their families and friends, and in themselves.

One man had considered suicide because of extreme and constant pain related to a treatment complication. This man could not fathom experiencing something so intense every day for the rest of his life. Death was seen as an escape from seemingly endless pain. However, this man found strength from his faith in God and in the support of family, to pull him through that dark period to a new beginning. He indicated that his faith made him realize that it was not his time to die, and he decided to start over and fight the cancer:

You know that thing [suicide], every day it crosses your mind, but you know if you're strong, you're not gonna do it, but you know sometime, it crosses your mind. You know if things aren't over, I feel this pain every day you know. But you know, like you say, when you have faith, you deal with it.

In addition, many men said they wanted to live for the sake of their families. Men expressed that they valued life above all else, despite the severity or inconvenience of their treatment. Faith enabled this change in perspective.

INTEGRATING PROSTATE CANCER INTO LIFE: PURPOSEFUL ACCEPTANCE OR RESIGNATION

Faith in a higher power helped the men to accept their diagnosis as fate or God's will and to integrate the experience into their lives. Their views changed from cancer as a death sentence at the time of diagnosis to prostate cancer as planned by God to serve a purpose in their lives and the lives of others as they completed their treatment. This represents a purposeful acceptance of the disease:

God got me through all the urine and impotence stuff and has been my hope for the future. There is a godly purpose for facing cancer, even if we don't know it, and to face cancer is one part of the journey with God, and to help others.

Men talked of now seeing that cancer was an event in their lives, albeit unexpected. Some men even saw prostate cancer as a way of testing their faith, which ultimately brought them closer to God who was a source of empowering strength for them. The prostate cancer had become a part of their lives by serving a purpose.

However, a difference was seen between this purposeful acceptance and resignation to cancer as a way of coping with the prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment. With resignation, there was not an active acceptance of the diagnosis, but an attitude expressed as “what more can I do.” Some men saw resignation as giving their problems and worry over to a higher power, so in that way they felt better being relieved of responsibility. Resignation meant their problems were no longer their own, but were shared with God. If they did not have the power to deal with the prostate cancer, God did, and in this way, they were able to cope with the cancer and incorporate it into their lives.

As men used faith to accept and integrate their cancer into their lives, they expressed hopefulness for the future. The one participant who had contemplated suicide and the men who were fearful because they could not see a future for themselves had survived and expressed a sense of having overcome the cancer. They felt that they had been through the worst of the adverse effects and tackled their fears about cancer. These men reflected on what they had been through, feeling that the worst was now behind them. This gave them hope for a future in which they could continue to cope with cancer and have a fulfilling life.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that faith, as a manifestation of spirituality, supports positive coping by low-income African American/black men treated for prostate cancer as they deal with the shock of their diagnosis. It gives them a framework to reframe perceptions such that they integrate the illness experience into their lives through purposeful acceptance or resignation. Faith took on a much broader context than religion alone. Faith was a motivator of and source for action. As these men dealt with treatment and symptom management, faith was used as an empowering force that freed them to be active participants in their treatment and incorporate treatment outcomes, even undesirable symptoms such as ED and incontinence, into their lives in a meaningful way. Faith was multifaceted and not necessarily limited to religious practice or to faith in a spiritual being. Faith was evidenced in the men's talk of existential concerns and struggles as they dealt with their disease. It provided a way by which men could move from facing a death sentence to integrating the prostate cancer into their lives and feeling a sense of having a new beginning, which was similar to the findings of Maliski and colleagues22 in an earlier study with a group of affluent, white men. Having had the strength to fight for life through use of faith gave new meaning and value to life. This sense of faith empowered an active participation in and cooperation with treatment. Even men who resigned themselves to living with adverse effects expressed a new sense in the value of life.

Our findings suggest consistency with others that indicate that low spirituality may negatively affect quality of life,18 even though we did not study those with no or low spirituality. In 1 study, Walton and colleagues identified the roles spirituality played across various phases of coping with prostate cancer.4 Consistencies in our findings included shock and fear at the diagnosis, having faith that allowed release of fears, and developing a new way of looking at the future that involved an increased awareness of the value of life and relationships. A major difference between our findings and those of Walton and Sullivan's4 was that their study indicated that trust was developed in self and surgeons through a process of information gathering and decision making based on that information. This was not seen in our results, perhaps because as uninsured, minority men, they did not have the options and resources available to the men in Walton and Sullivan's4 study or Maliski and colleagues'22 earlier study. This lack of financial resources may make faith an even more important coping resource in underserved populations. However, this bears further investigation. The perceived threat to one's life precipitated by the prostate cancer diagnosis also influences faith by strengthening links with a spiritual community, increasing feelings of gratitude toward life, and improving personal relationships.23 Consistent with our findings, it has been shown that religion-affiliated, uninsured patients demonstrate adequate coping and more hopeful attitudes toward their pain and symptom management24 and that African Americans/blacks perceive cancer survival as a gift from God, making “giving back” an important part of their faith.25 Part of the new beginning was a desire to be a good example or to spread the word to other African American/black men about prostate cancer.

Harvey and Silverman,3 who studied spirituality in African Americans and whites, showed that racial differences exist in the role of spirituality in self-management behaviors. For example, whites were more likely to integrate spirituality into self-management practices, whereas African Americans were more likely to endorse faith in divine intervention. Participants in our study used their faith as a source of strength for coping with a difficult situation, including dealing with symptoms and their management. However, they did not voice looking for divine intervention without any work on their part. Rather, their faith was a means by which they were empowered to participate in their care.

The men in our study saw cancer differently than has been found by some other investigators. White and Verhoef23 found that participants did not view cancer as a threat or intruder but a presence with which they needed to cooperate. The men in our study went so far as to personify cancer as a visitor in their bodies, one that did not have a permanent presence and was not welcome. There was no sense of cooperation with the cancer in these men's stories. One possible reason for this discrepancy was that the study performed by White and Verhoef23 investigated reasons that men forego conventional prostate cancer treatment for alternative medicines and the significance of spirituality in that decision rather than faith's function in living with cancer.

The new-beginning category that emerged in our data shows similarities with Tedeschi and Calhoun's26 formulation of personal growth following a traumatic or stressful event. Changing perceptions of the cancer, improving relationships, renewing faith, and having faith in self, God, providers, and family are consistent with the concepts of making a crisis manageable and comprehensible.

Some caution needs to be exercised in interpreting the findings of our study. The coping process and responses given by these men are unique to their lives and experiences and not meant to be broadly generalized to all African American/black men. Although we cannot expect their thoughts to be the same, what we can infer is that they have similar values, concerns, and personal and relational conflicts as other low-income African American/black men. As such, we can expect men in this population to experience similar uses of faith. Second, the study may not represent all religious beliefs. The religion that predominates among African American/black men is Christianity. However, we did not ask our participants about their religious affiliation. Therefore, our findings may not provide insight on how African American/black men of specific religions would use faith to deal with prostate cancer and its treatment. Our study explored faith, a concept less rigid than religiosity, which was not confined to a particular religion or belief system. Those of all religions and outside religion can have faith in this broader sense of the concept. Lastly, older men are underrepresented in this study. The participants were chosen from the underinsured or uninsured men from the IMPACT program. Because Medicare starts at 65 years and is insurance, Medicare enrollees were not eligible for this study. According to Harvey and Silverman,3 spirituality is an important component of the lives of elder African American men. Additional study with older men is warranted. In addition, all of the men in this study talked about using faith to cope with there prostate cancer. All participants in our study utilized faith as a coping mechanism. Therefore, we do not know what other processes might be used by these men, which warrants further study.

Despite these limitations, the results of this study provide valuable insights into the coping resources used by low-income, uninsured African American/black men with prostate cancer and the role that faith plays as one of those resources. By understanding faith as a source of empowerment for active participation in care and in integrating the prostate cancer experience into the life story, oncology nurses can use men's faith, when assessed as appropriate, to facilitate reframing of perceptions of cancer. By acknowledging the role of faith in handling “fate,” the provider can assist men in using faith to participate actively with health care providers. Assessment of strengths of African American/black men needs to include their use of faith and in whom they place their faith when dealing with difficult situations. Additional studies are needed to determine if this model is relevant across various beliefs and cultures and whether faith can encourage passivity in some circumstances. The possibility that faith may play a larger role among underserved groups with limited resources also bears further investigation.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Department of Defense (PC030104 and IMSD GM55052).

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. National Home Office, American Cancer Society, Inc; Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey I, Silverman M. The role of spirituality in the self-management of chronic illness among older African and whites. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2007;22:205–220. doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9038-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walton J, Sullivan N. Men of prayer: spirituality of men with prostate cancer: a grounded theory study. J Holist Nurs. 2004;22(2):133–151. doi: 10.1177/0898010104264778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phelps A, Maciejewski P, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;18(301):1140–1147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jim H, Richardson S, Golden-Kreutz D, Andersen B. Strategies used in coping with a cancer diagnosis predict meaning in life for survivors. Health Psychol. 2006;25(6):753–761. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ka'opua A. Spiritually based resources in adaptation to long-term prostate cancer survival: perspectives of elderly wives. Health Soc Work. 2007;32(1):29–39. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.King M, Koenig H. Conceptualising spirituality for medical research and health service provision. BMD Health Serv Res. 2009;9:116–122. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawson E, Cecelia T. Wading in the waters: spirituality and older black Katrina survivors. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18:341–354. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meier A, Rudwick E. From Plantation to Ghetto: An Interpretive History of American Negroes. Hill and Wang; New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Foner P. History of Black Americans: From the Emergence of the Cotton Kingdom to the Eve of the Compromise of 1850. Greenwood Press; Westport, CT: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 12.DuBois W. Black Reconstruction in American, 1860–1880. Athenum; New York: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blocker D, Romocki L, Thomas K, et al. Knowledge, beliefs and barriers associated with prostate cancer prevention and screening behaviors among African-American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(8):1286–1295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krause N, Van Tran T. Stress and religious involvement among older blacks. J Gerontol. 1989;44(1):S–13. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.1.s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klonoff E, Landrine H. Belief in the healing power of prayer: prevalence and health correlates for African American women. West J Black Stud. 1996;20(4):207–210. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waite P, Hawks S, Gast J. The correlation between spiritual well-being and health behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 1999;13(4):159–162. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-13.3.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levin J. How faith heals: a theoretical model. Explore. 2009;5:77–96. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krupski TL, Kwan L, Fink A, Sonn GA, Maliski S, Litwin MS. Spirituality influences health related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(2):121–131. doi: 10.1002/pon.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zavala MW, Maliski SL, Kwan L, Fink A, Litwin MS. Spirituality and quality of life in low-income men with metastatic prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(7):753–761. doi: 10.1002/pon.1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maliski S, Rivera S, Connor S, Lopez G, Litwin M. Renegotiating masculine identity after prostate cancer treatment. Qual Health Res. 2008;18(12):1609–1620. doi: 10.1177/1049732308326813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. 2nd ed Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maliski SL, Heilemann MV, McCorkle R. From “death sentence” to “good cancer”: couples' transformation of a prostate cancer diagnosis. Nurs Res. 2002;51(6):391–397. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200211000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White M, Verhoef M. Cancer as part of the journey: the role of spirituality in the decision to decline conventional prostate cancer treatment and to use complementary and alternative medicine. Integr Cancer Ther. 2006;5(2):117–122. doi: 10.1177/1534735406288084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Francoeur RB, Payne R, Raveis VH, Shim H. Palliative care in the inner city. Patient religious affiliation, underinsurance, and symptom attitude. Cancer. 2007;109(2 suppl):425–434. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton JB, Powe BD, Pollard AB, 3rd, Lee KJ, Felton AM. Spirituality among African American cancer survivors: having a personal relationship with God. Cancer Nurs. 2007;30(4):309–316. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000281730.17985.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tedeschi R, Calhoun L. Trauma & Transformation: Growing in the Aftermath of Suffering. Sage Publication; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1995. [Google Scholar]