Abstract

Extant ethnographic studies suggest that the nuclear family has been the predominant living arrangement in Cambodia, and the country’s rapid socioeconomic transformation since the early 1990s may have accentuated that dominance. To examine these claims, we analyse here household structure in Cambodia between 1998 and 2006, based on data from the 1998 Census, two nationally-representative surveys (2000 and 2005), and a continuing demographic surveillance system (from 2000 on). Our analysis confirms the large prevalence of nuclear families, but not an unequivocal trend toward their increasing prevalence. First, nuclear families are less prevalent in urban than in rural areas, and nationwide, they appear to have receded slightly between 2000 and 2005. We find that increases in the prevalence of extended households correspond to periods of faster economic growth, and interpret these contrasted trends as signs of tensions during this transitional period in Cambodia. While the nuclear family may still be the cultural norm, a high degree of pragmatism is also evident in the acceptance of other living arrangements, albeit temporary, as required by economic opportunities and housing shortage in urban areas.

Keywords: Cambodia, household composition, living arrangements, family structure, kinship

In this paper, we analyse recent data on household structure in Cambodia between 1998 and 2006. We begin by briefly placing our analysis in the context of anthropological studies on kinship in Cambodia before the Khmers Rouges (KR), and in other countries in Southeast Asia, mostly neighbouring Thailand and Vietnam.

Our analyses are based on the 1998 General Population Census (GPC 1998) and the first two Cambodia Demographic and Health Surveys (CDHS 2000 and CDHS 2005), which provide the first nationally representative data on household structures in Cambodia since the KR. The GPC 1998 and CDHS surveys provide estimates at different points during the past decade, and interpreting differences as changes over time requires comparability across these different data sources. As this is always difficult to ascertain, we also explore household structure from a non-nationally representative, but longitudinal data collection project. The Mekong Island Population Laboratory (MIPopLab) is a demographic surveillance system launched in 2000 with biannual demographic updates on the population of a circumscribed rural area. While not representative of the whole country, the demographic data from this area can be located within the pattern of regional diversity clearly observable in Cambodia.

Background

In sociology, anthropology, and economics, the family is a core analytical concept, and a substantial body of studies is devoted to individual interactions within the family and its role relative to households and kinship. In contrast, until recently, demography neglected the study of the household and primarily focused on the individual (Bongaarts 2001). Formal single-sex population models are a case in point. Potential analytical challenges (e.g. the two-sex problem) are compounded by empirical deficiencies in the study of many historical populations and still quite a few contemporary ones. The corroboration with population-level demographic data of attempts to characterize family systems originating in other disciplines has also proved difficult.

At the most general level, the Asian family is often taken to represent the counterpart of the European ‘nuclear family’ ideal type, and thus, as the enduring bastion of the extended family: several generations living in the same household. Within Asia, however, there are unmistakable differences in family forms (Mason 1992; Das Gupta 1998). In East Asia and stretching as far south as Vietnam, in countries influenced by Confucianism and Mahayana (large-vehicle) Buddhism, the ideal family type is patriarchal, patrilineal and virilocal. The newly married couple generally lives with the groom’s family for a long time, if not permanently. Where Theravada (the elders’ way) Buddhism dominates, in Sri Lanka and most of continental Southeast Asia, including Myanmar, Thailand, and Cambodia, the family system is quite different. While in Cambodia its exact characterization may remain a matter of scholarly dispute (see Népote 1992), kinship relationships appear to be bilateral: in contrast with the patrilineal clans, people relate equally to their blood relatives on the maternal and the paternal side (Ledgerwood 1995). In contrast with the patriarchal system, family law suggests equality between wife and husband in case of divorce and between sons and daughters in inheritance rules (Lingat 1952). This family system has been described as uxorilocal because traditionally married couples live at first with the brides’ parents (Hirschman et al. 1996), but also as neolocal to the extent that married couples are expected to establish independent households as soon as material conditions allow. Regardless of the exact label, the tendency is toward nuclear families rather than extended ones, as documented in the case of Thailand (Smith 1973).

Clearly within the realm of Theravada Buddhism, the family in modern Cambodia has been subjected to several other potential influences. The French Protectorate in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries appears to have had no noticeable influence on the Khmer family system (Migozzi 1973; Népote 1992; Ovesen et al. 1996). Ethnographic studies of the Khmer family around the time of Cambodia’s independence reflect a general endorsing of the above-described schemas, bilateral lineage, uxorilocal then neolocal residence, relative gender-equality, but also a lot of flexibility and pragmatism in family forms as may be required to adapt to economic opportunities (Ebihara 1968; Martel 1975). The short-lived Khmers Rouges regime had a much more dramatic impact on the Khmer family.

The Khmer family and the Khmers Rouges: a before and an after?

Shortly after entering Cambodia’s capital city, Phnom Penh, on 17 April 1975, the KR claimed on the airwaves that 2,000 years of Cambodian history had ended. However hyperbolic the statement, the three years, eight months, and 20 days of the KR rule over Cambodia do represent such a dramatic chiasm in the country’s recent history that one is drawn to consider pre- and post-KR Cambodia separately. The social transformation undertaken by the Khmers Rouges is arguably the most radical and fast-paced one ever attempted (Kiernan 1996; Weitz 2003). Its demographic impact has been profound, most dramatically in terms of excess mortality (Sliwinski 1995; Kiernan 1996; Heuveline 1998), birth dearth (Heuveline and Poch 2007), and distortions in age structure and sex ratio (Huguet 1992).

The KR’s social reformation also included a frontal attack on the family, which it saw as the core institution of social reproduction. Individuals were reminded that their allegiance should be turned away from family members towards the higher echelon of the political structure, the Angkar, and youths in particular were brainwashed to ignore the strong cultural emphasis on respecting and repaying one’s elders. Even marriages were taken away from families to become arrangements between two individuals and the State (Heuveline and Poch 2006). Unfortunately, we are not aware of any study attempting to trace the durable effects that in little less than four years the KR may have left on family relationships in Cambodia. Sliwinski (1995) argues, plausibly, that social trust has been dramatically damaged by the traumatic experience of the KR regime, but offers no supporting evidence. Early ethnographic studies actually suggested that social solidarity rarely extended much beyond the immediate family (Ebihara 1968; Martel 1975), as aptly captured by Ovesen et al. (1996) in their monograph’s title Every Household Is an Island. Meanwhile, survivors’ accounts provide a consistent picture of resilient families that kept mentally connected even during long periods of physical separation and while KR cadres threatened people into abandoning expressions of familial attachment (e.g. Pran and DePaul 1999). One of the contributing factors to the 1979 famine was the fact that as soon as the KR retreated in front of the advancing Vietnamese army, rice fields were abandoned by people travelling on foot in search of their family members.

Modernization and family changes in post-KR Cambodia

The Vietnamese troops entered Cambodia in December 1978, and although they quickly defeated the KR army, they remained in Cambodia for a decade, fighting a guerrilla war with the remaining KR soldiers at the Thai border. During that period the Cambodian government and its public infrastructure, such as schools and health clinics, were supported directly by Vietnam and more generally by the Soviet Union and its allies, while remaining politically, economically, and culturally isolated from other countries. In spite of the continued fighting and of the massive number of land mines still buried in the Cambodian soil, mortality declined rapidly, fertility rebounded, and literacy improved during the period. Oral accounts indicate that religious and family ceremonies were also promptly restored.

With the withdrawal of Vietnamese troops in 1989, the signing of the multi-party Paris Agreement in 1991, and the United Nations sponsored elections in 1993, Cambodia gradually re-entered the international community, politically as well as economically. Literacy and public health continued to improve slowly, but new family trends developed. The clearest sign of a reversal is in the area of family size, with a marked fertility decline. Recent data are not entirely consistent regarding the precise level of contemporary fertility, as indirect estimates of the GPC 1998 data yielded a total fertility rate (TFR) of 5.3 (NIS 1999a), while direct estimates from the CHDS 2000 and 2005 yielded 4.0 and 3.4 respectively (NIH 2001, 2006). The actual pace of the fertility trend may not be entirely clear, but the decline is beyond dispute, as after the fall of the KRs fertility rebounded and exceeded pre-KR levels (Heuveline and Poch 2007), which analyses of the 1962 census data put at about seven children per woman (Siampos 1970).

Even more difficult to measure precisely, change to what are considered in Cambodia as traditional family forms also seems to have happened (Heuveline and Poch 2006). ‘Romantic’ marriages with self-chosen spouses are gradually becoming more common, about 24 per cent among 1986–1999 marriage cohorts, and so are divorces and separations, still at a modest level of about six per cent of marriages ending in divorce by year 5 among the 1993–1999 cohorts. These trends coincide with the development of a garment industry and a tourist industry that provide Cambodia’s young adults with job opportunities that are not as closely monitored by their parents as the agricultural sector. A causal relationship between these economic changes and family trends is quite plausible although difficult to establish conclusively.

Arguably, the KR attack on the family had only a temporary effect that faded away as soon as their leaders fled, but the undergoing modernization of the Cambodian economy and society may cause more durable change (Hirschman and Edwards 2007). There is still considerable debate on the exact contours of the effect of economic and social change on the family, however. Rooted in the grand modernization theories of the 1960s (e.g. Rostow 1960), the family patterns convergence theory (Goode 1963), just like the demographic transition theory, has seen its paradigmatic domination challenged in recent years. The postulate was relatively straightforward:

Wherever the economic system expands through industrialization, family patterns change, extended kinship ties weaken, lineage patterns dissolve and a trend toward some form of the conjugal system generally begins to appear – that is, the nuclear family becomes a more independent kinship unit (Goode 1963: 6).

The argument, however, has been criticized on several fronts: (1) extended families were not necessarily prevalent to begin with in many pre-industrial societies (Bongaarts 2001); (2) in some other societies, extended families were prevalent but have remained so in spite of modernization, for example China (see Stokes et al. 1987; Tsui 1989) or India (Ram and Wong 1994); and (3) the nuclear family is not necessarily a stable family pattern in industrial societies (Heuveline et al. 2003).

Stepping back from grand theoretical generalization, more recent research emphasizes the family as an adaptive institution that changes with the larger environment in which families operate in order to continue to provide economic and psychological support to its members (Todd 1999; Derosas and Oris 2002). Laslett’s (1988: 156) ‘hardship hypothesis’ points out that in countries lacking national welfare institutions—such as Cambodia—kinship remains the only source of support for families in precarious life situations such as illness, ageing, widowhood. Thus, with modernization, the more widespread the nuclear family, the more individuals’ adaptations could be detrimental to some family members, to older people, for instance, but this hypothesis is still contested (e.g. Ruggles 1996; Das Gupta 1998). In any event, recent research has produced examples in which the multigenerational family has become more prevalent in the face of unemployment, marital disruption (Pearson et al. 1990; Ford and Harris 1991; Lee 1999) and poverty (Antoine et al. 1995). The extended family can also emerge in the urban areas of developing countries, as a result of internal, work-related migration (Vimard 2003; Pilon 2004).

Data and Methods

Data

Data from quantitative surveys in developing countries are often inadequate or insufficient. There were no demographic data surveys from the mid-1960s to the early 1990s, but international agencies sponsored several key nationally representative surveys. The three recent data sources on the contemporary Khmer population analysed here are the GPC 1998, the CDHS 2000 and 2005, and MIPopLab.

A subsample of the GPC 1998, the first census conducted since 1962, is available online at IPUMS-International, a web-based data dissemination system. The database, provided by the Cambodian National Institute of Statistics, is a self-weighted, 10 per cent sample of the de facto census population, consisting of 1,141,254 individuals. Although the macro characteristics of census data significantly restrict the analysis of family structure, the data allow us some analysis of residential patterns, such as the size and composition of households, at the outset of a period of drastic changes in Cambodian family demography.

The CDHS 2000 and CDHS 2005 are a second source of data. They are statistically representative at the national level and include both a household questionnaire (12,236 households in 2000 and 14,243 in 2005) and a women’s questionnaire (15,351 15-to-49 year-old women in 2000 and 16,823 in 2005). The information collected in the household survey is essentially oriented towards identifying these women of reproductive age, and from the standpoint of family demography, there are several unfortunate data gaps. The household questionnaire is nonetheless useful as it contains information about residential patterns (urban-rural residence or amenities), and a list of all individuals present (de facto) in the household. For each of those, variables such as age, sex and education and residential status are available. Although the women’s questionnaire is focused on women’s health and fertility, it also provides useful information on women’s family income, including loans and parental financial assistance.

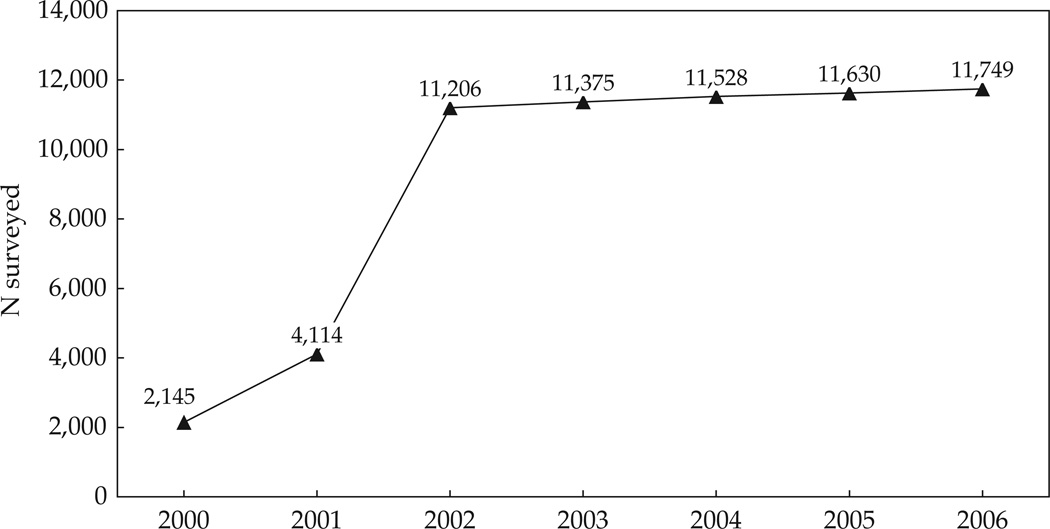

The cross-sectional nature of these data provides a limited snapshot of family formation. Goody (1971) argues that if households are only analysed at the time of a census but not in terms of the ‘developmental cycle’ (Goody 1995), the results fail to reflect family formation as an evolutionary process. A multigenerational family could be a transitional structure to several household units, for example. Thus, analysis of family transformation and structural evolution requires longitudinal data over an extended time. The census and surveys described above do not allow for longitudinal analysis. By contrast, the MIPopLab database is longitudinal, but not nationally representative. MIPopLab is a demographic surveillance system (DSS) launched gradually, starting in one village in December 2000, expanded to five villages by July 2002, and updated twice a year since. The total population size followed-up in MIPopLab over time is shown in Figure 1. The basic demography of the entire island population of 11,749 (in 2006, corresponding to the 12th round) is included in the interviews. For each member of the household, variables such as age, sex, marital status, location, survival of parents and relationship to the head of the household are known. Events such as marital disruption or remarriage, in- and out-migration, deaths and births are registered every six months. Located in Kandal, a province surrounding the Phnom Penh Province (PPP, where the capital city is located), this population is not representative of Cambodia. However, because of its geographical location between the urban capital and its rural province, many demographic features such as fertility or marriage appear to match national trends (Heuveline and Poch 2007). Thus, this local, multiround longitudinal data source complements the macro-characteristics of household diversity and change captured in the GPC 1998, the CDHS 2000, and the CDHS 2005 data and allow us to approach individuals’ trajectories.

Figure 1. year-end total sample size, Cambodia, 2000–2006.

Source: Author’s calculations from MIPopLab data.

Finally, these Cambodian cross-sectional and longitudinal quantitative results are put into perspective by comparison with data from Thailand and Vietnam, when available. We compare the results from these three populations in an effort to isolate features specific to the Khmer family. Concerning Vietnam, the 1989 and 1999 Census databases were used; they are available online at IPUMS-International. Like the data for Cambodia, those include a self-weighted, 10 per cent sample consisting of 2,626,985 households in 1989 and of 2,366,926 households in 1999. In contrast, Thai censuses are not available online up to date. The National Statistical Office of Thailand provides, however, information about the mean household size.

Methods

This paper attempts to analyse the demographic dynamics of Cambodian family units in size, composition and structure in a period of rapid contextual change, albeit on a very short timeframe (1998–2006). A first concern is the pertinence of ‘household’ rather than ‘family’ terminology, which has often been debated in family demography papers (McDonald 1992; Burch 1993). Censuses and surveys are household-based mostly for logistical reasons, and household and family memberships only partly overlap, as families may spread across different connected households, sometimes adjoining ones. A few questionnaire items may still allow analysts to study family behaviour across households. We thus merged the CDHS household and women’s questionnaires to examine some of these family links across households, but we recognize that we are mostly limited to studying households rather than families. The CDHS women’s questionnaire provides more information in the area of kinship-solidarity networking and household resources and amenities. Another item in the CDHS women’s questionnaire documents whether the family is close enough to visit easily, defined in the questionnaire as being less than an hour away. Furthermore, the women’s questionnaire contains the interesting variable ‘Wealth Index’ of a woman’s household. The DHS ‘Wealth Index’ captures households’ relative socio-economic status from existing data in the DHS. The explanatory and comparative power of this Wealth Index is demonstrated in many comparative studies (e.g. Vyas and Kumaranayake 2006). In our context, the index allows us to test Laslett’s (1988) ‘nuclear hardship’ hypothesis. This index uses all household assets (radio, bicycle, etc.) and amenities (type of flooring, type of toilet facilities, etc.) available in the survey as an economic indicator. First weighting values are assigned to the indicator variables by PCA procedure (see Filmer and Pritchett 2001). After this standardization, the factor coefficient scores are calculated. Then, for each household, the indicator values are multiplied by the loadings and summed to produce the household’s index value. The resulting sum is itself a standardized score with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one, from which we created three categories, based on the distribution of the household population, to distinguish the ‘poorer’, ‘middle’ and ‘richer’ households.1

All these surveys and censuses also provide the relationship of each person listed in the household to the head of that household. Drawing upon the typology that Hammel and Laslett (1974) developed to analyse nineteenth-century European family structure, we use a similar typology adapted to contemporary Southeast Asia. Specifically, we begin with the same categories of ‘simple family unit’2, for a household containing the head, his wife and his children, ‘multiple or extended’3, for a multigenerational household containing a grandchild (downward) and/or a parent (upward) of the head; and ‘isolated’, for a single-member household. We then identify more contemporary structures including the ‘lone-parent family’ (women or men alone with children), and the ‘co-resident siblings’ as well as a residual ‘other household’ structure.

Trends in household structures reconstructed from the reported relationships to the household head may be biased by the varying level of detail from one survey to the next: seven in the GPC 1998, 12 in the CDHS 2000 and 2005 and from eight initially to 31 currently in the MIPopLab database. We attempted to reduce this problem by adapting the definition of each structure when necessary. Tests showed that the results are consistent for the CDHS and MIPopLab data. Differences between the GPC 1998 census and CDHS 2000 appear too large to be entirely attributable to demographic change in the two-year period. Overall, however, trends in family structures are broadly consistent between the surveys used in this analysis.

Demographic changes such as fertility and mortality have a significant effect on family structure. The probability that a head of household will form an extended family in the future depends upon the number of children in the family, while a high level of mortality such as Cambodia experienced during the 1970s reduces the availability of kin to form joint households. Cross-sectional household analysis thus needs to take into account this changing context. To that effect, we assess a measure of intergenerational co-residence that is less sensitive to those demographic effects. However, the proportion of elderly persons residing with any child, we calculated, is slightly underestimated compared with the UNFPA Report’s results (Knodel et al. 2005). Indeed, if the elderly person is neither a parent of the head of the household, nor the head or the spouse, it is impossible in the GPC or CDHS data to know whether an elderly person is living with a child.

MIPopLab data allow us to go one step beyond residence patterns at the household level and study individual trajectories. The widely free ‘R’ software and a new package called ‘TramineR’, having individuals as observation units, and developed by G. Ritschard, A. Gabadinho and N. Müller of the University of Geneva, have been used to provide individual trajectories and transition matrix. These are analysed with respect to age and sex, because of the salience of the hierarchies and roles associated with age and sex in Cambodia, but also generation, because of the potential impact of having lived through the Khmer Rouge period. The results reported in this study remain largely descriptive, however, and aim to provide an overview of the diversity and change in Cambodian households between 1998 and 2006, with respect to household size, composition and structure.

Results

Household Size

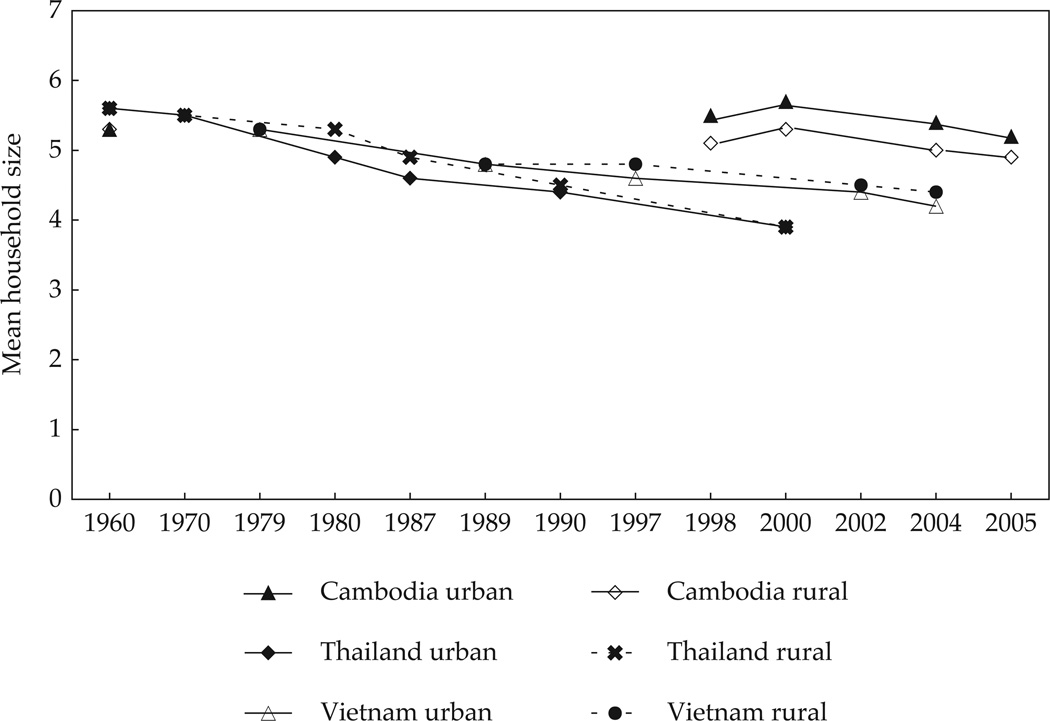

We begin by presenting analysis of the composition of the households and its dynamics. Figure 2 presents the mean household size for Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam, on a de jure basis (members who usually reside in the household.) This preliminary indicator reveals that in the 1990s, households were larger, on average, in Cambodia than in its two neighbouring countries. In the early 1960s, however, Cambodia’s mean household size (5.3) appears to have been slightly lower than in Thailand (5.6). We have unfortunately no data available to date when the average Cambodian household became larger than its Thai or Vietnamese counterparts.

Figure 2. Mean household size in Cambodia, tha thailand and vietnam.

Sources: Burch 1967; Siampos 1970; Pilon 2004; United Nations 2007; Authors’ calculations from the Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), and from national censuses and surveys.

As discussed in the background section, the Thai and Khmer family systems share key characteristics. The slightly smaller average size for Cambodian households in the 1960s is probably due to the smaller number of children alive rather than to differences in the structural composition of households. For 1955–60, the infant mortality rates are estimated at 152.0 in Cambodia and 99.6 in Thailand, while TFRs are 6.3 in Cambodia and 6.4 in Thailand (United Nations 2007). The average size of the Thai and Vietnamese households is similar until the late 1980s, at which point the average household size declines slightly faster in Thailand than in Vietnam. The contrast is starker, however, with the trend in Cambodia, where the average size did not decline until 2000, when it declined slightly from 5.3 in rural areas (to 4.9 in 2005) and from 5.7 in cities (to 5.2 in 2005). The up and downs in average size are related to the ups and downs in fertility rates, in particular the ‘baby boom’ of the early 1980s, and the rapid decline in the 1990s (Heuveline and Poch 2007). The timing of the decline in household size and that of the period fertility change are at odds during the 1990s, but household size should reflect cumulative fertility (parity) rather than current fertility rate factors. We cannot conclude from these data alone whether factors other than fertility contributed to these divergent household-size trends in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam.

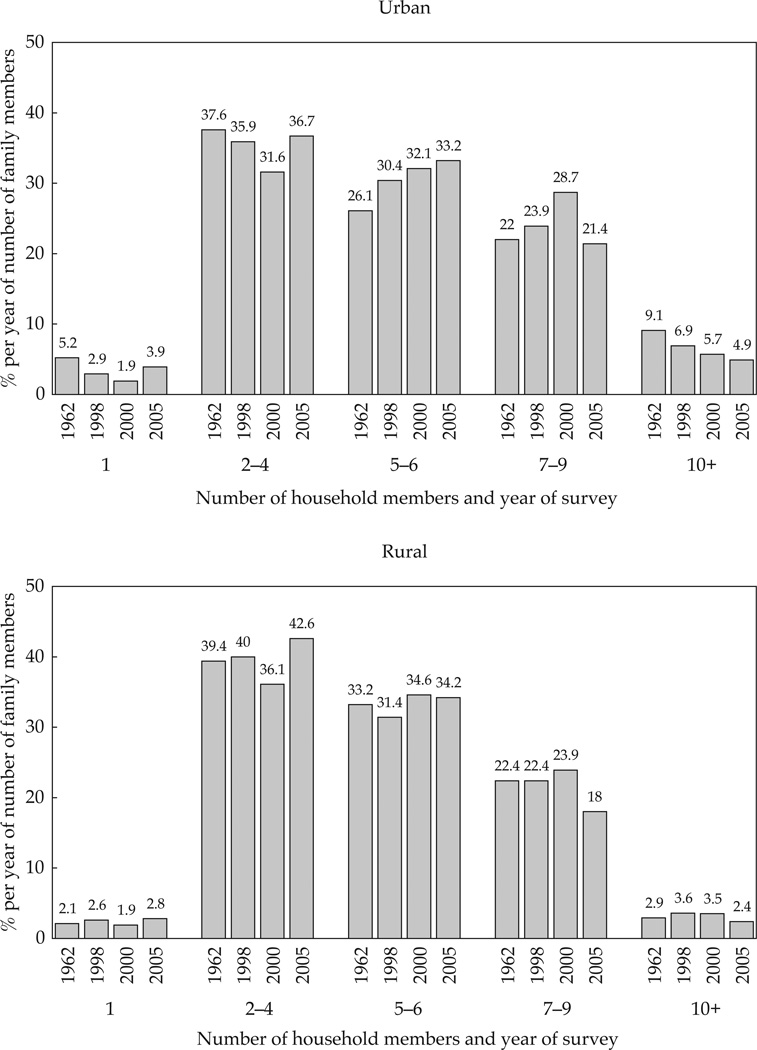

As the next step forward, we analyse the urban and the rural distributions of households with one, with two to four, with five to six, with seven to nine, and with ten and more members for four different years. As shown in Figure 3, families consisting of one to six members represent more than 80 per cent of contemporary Cambodian families. Households of seven or more members still represent about 20 per cent of the total, although the proportion of households with ten or more members is small and declining. Surprisingly, however, large families are more prevalent in urban areas. This seems to indicate that they do not correspond to a traditional pattern, but rather constitute a new trend.

Figure 3. Households by size, urban and rural areas, Cambodia, 1962, 1998, 2000, and 2005.

Sources: Migozzi 1973; Authors’ calculations from the 1998 Census of Cambodia data files, and the 2000 and 2005 Cambodian DHS data files.

In urban areas, until 2000, the proportion of smaller families (four or fewer members), decreased, and the proportion of medium and large families (five to nine members) increased. After 2000, the increase shifted to small and medium-size families (less than six), whereas the proportion of larger families (seven or more) decreased. In rural areas, the distribution of households remains relatively stable until 2000, when the proportion of larger ones (seven or more members) declines and that of smaller households (four or fewer members) increases.

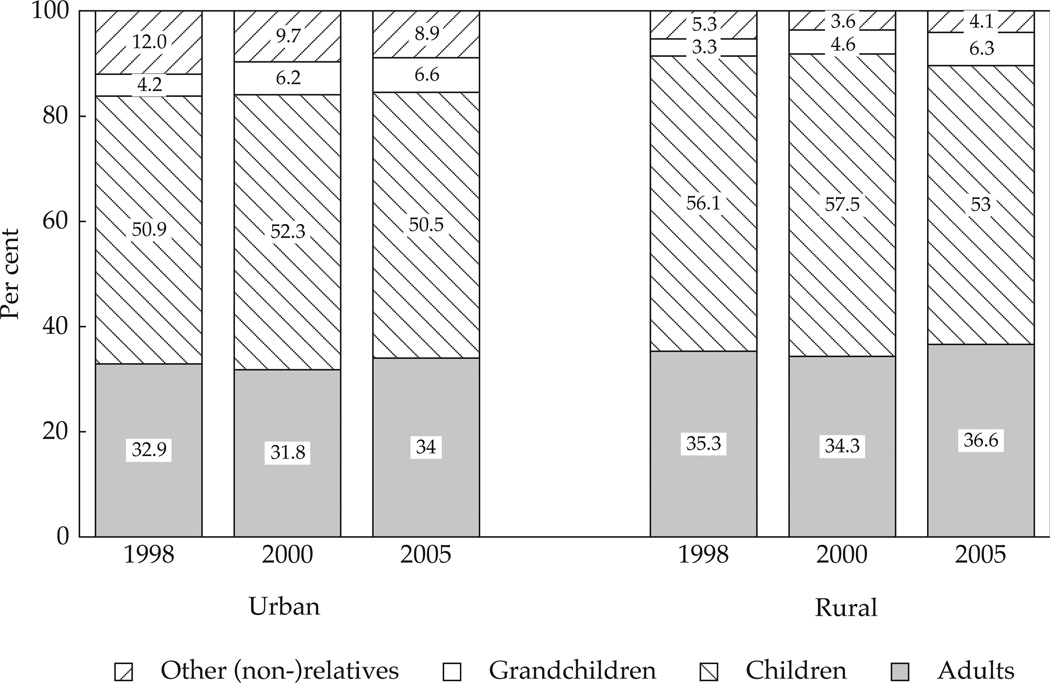

Household composition

We continue our analysis with a decomposition of individuals’ relationship to the head of the household. As illustrated in Figure 4, being a child of the household’s head constitutes the most common category in both urban and rural areas. In addition, there are very few households without any child (less than 1.5 per cent of the families with a head and a head’s spouse in any of the three surveys, results not shown).4 The mean age of these children varies from 10.8 years in the 1998 Census to 13.3 years in the 2005 CDHS. The proportion of children is larger in rural than in urban families. In 1998, 50.9 per cent of urban residents were children of their household heads, compared to 56.1 per cent among rural residents. By 2005, those proportions had declined only slightly to 50.5 per cent in urban areas and 53.0 per cent in rural areas.

Figure 4. Household members by relationship to head, urban and rural areas, Cambodia, 1998, 2000, and 2005.

Sources: Authors’ calculations from the 1998 Census of Cambodia data files, and the 2000 and 2005 Cambodian DHS data files.

The category ‘adults’ in Figure 4 represents the parents, biological or adoptive, and grandparents of these children: the households’ head and/or his or her spouse, and possibly their own parents.5 There is a greater proportion of adults in rural areas, 36.6 per cent in 2005, than in urban areas, 34.0 per cent in urban areas. As shown in the next section, this does not reflect single parenthood. It is due rather to the fact that urban households contain more individuals, non-relatives, or relatives other than their own children and parents. Indeed, the largest immigration flow to Phnom Penh is due to the increasing economic attraction of the capital (Table 1). Immigration to Phnom Penh for family reunification is also increasing. This reason motivates 47.1 per cent of all migration in 1998 and 54.6 per cent in 2004 (Author’s calculations from GPC 1998, Cambodia intercensal population survey report 2004). There is extensive job-related mobility toward urban centres, and probably to reduce expenses or to avoid unfamiliar settings, many of these migrants move into existing households. CDHS 2005 data included 8.9 per cent ‘other relatives’ or ‘non-relatives’ in urban areas and 4.1 per cent in rural areas.

Table 1.

Percentage distribution and density of population by broad age group, Phnom Penh, 1998 and 2004

| Age group | 1998 census | 2004 CIPS |

|---|---|---|

| 0–14 | 33.1 | 27.8 |

| 15–49 | 57.3 | 60.1 |

| 50–64 | 6.8 | 8.8 |

| 65+ | 2.8 | 3.3 |

| Density (per km2) | 3,448 | 3,783 |

With regard to trends over time, the proportion of children relative to that of their parents (heads and spouses) increases until 2000 and declines thereafter, in urban as well as in rural areas. If we analyse this trend further by age, we find that the decline is already occurring between 1998 and 2000 for children under age nine (results not shown). By 2000, the decline spreads to children in the age range 0 to 19 years. This is thus consistent with the cumulative effect of the fertility decline on household size and its possible effect on the above-discussed trends in average size over time.

Household structure

The breakdown of Cambodian families corresponding to our typology of household structures in Cambodia is presented in Table 2; this breakdown confirms the predominance of nuclear families in Cambodia. Over time, the nuclear structure peaks at 65.6 per cent of Cambodian households in 2000, which compares to 53.4 per cent in Vietnam at the time of the 1999 Census (results not shown; comparable data for Thailand not available). The proportion of extended households has followed a trend opposite to that of nuclear families, declining from 22.3 per cent in 1998, to 13.2 per cent in 2000 and a modest gain thereafter. Overall, the prevalence of extended households measured by cross-sectional data has declined between 1998 and 2005. This trend is even more meaningful considering the fertility and mortality decline in contemporary Cambodia. Indeed, the intergenerational co-residence measured by the elderly residence patterns (Table 3) follows obviously the same trends. Furthermore, the effect on household structure of recent fertility decline is quite small (less than 1 per cent, results not shown6). Vietnam provides another contrast, as the prevalence of extended families there remained at 30.1 per cent at the time of the 1999 census, down only slightly from 32.7 per cent at the time of the 1989 census (results not shown).7

Table 2.

Households by structure categories, urban and rural areas, Cambodia, 1998,2000, and 2005 (per cent)

| Rural |

Urban |

Country |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Household type |

1998 | 2000 | 2005 | 1998 | 2000 | 2005 | 1998 | 2000 | 2005 |

| Isolated | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.6 |

| Nuclear | 59.1 | 67.8 | 63.0 | 44.1 | 54.2 | 51.1 | 56.8 | 65.6 | 61.1 |

| Women alone with children |

9.7 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 8.6 | 13.3 | 11.0 | 9.5 | 12.4 | 11.9 |

| Men alone with children |

1.3 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Extended | 20.6 | 12.7 | 15.1 | 31.6 | 16.1 | 18.8 | 22.3 | 13.2 | 15.6 |

| Co-resident sibling | 2.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 |

| Other | 6.4 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 8.6 | 12.2 | 14.9 | 6.8 | 5.6 | 7.8 |

| N (households) |

184,670 | 10,419 | 11,142 | 31,531 | 1,817 | 3,101 | 1,141,254 | 12,236 | 14,243 |

Sources: Author’s calculations from the 1998 Census and the 2000 and 2005 Cambodian DHS data files.

Table 3.

Households with at least one member aged 60 and over by structure categories and co-residence with a child, Cambodia, 1998, 2000, and 2005 ( per cent)

| Aged 60+ |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2000 | 2005 | |

| Household type | |||

| Isolated | 3.6 | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| Nuclear | 29.8 | 23.5 | 37.2 |

| Women alone with children | 5.7 | 3.8 | 14.4 |

| Men alone with children | 1.8 | 1.4 | 2.9 |

| Extended | 39.2 | 60.2 | 31.3 |

| Co-resident siblings | 2.3 | 4.0 | 0.7 |

| Other | 17.6 | 4.2 | 9.7 |

| Elderly person residing with any child | 73.0 | 71.7 | 68.6 |

| N (individuals) | 60,324 | 3,516 | 4,548 |

Sources: Author’s calculations from the 1998 Census and the 2000 and 2005 Cambodian DHS data files.

Table 2 also shows that the above described dynamics applies to both the rural and the urban areas. The prevalence of nuclear families is greater in rural areas, however, than in urban areas. The gap appears to be closing from 1998 (59.1 per cent in rural and 44.1 per cent in urban areas) to 2005 (63.0 per cent in rural and 51.1 per cent in urban areas).

Women living with children and no spouse constitute the third category of household that displays important changes over time. This category accounts for about one in eight households in Cambodia since 2000. Further analysis revealed that among these women, 37 per cent were single women in 2005, 23 per cent were married but living separately from their husbands, essentially because of migration, 31 per cent were widowed, and 9 per cent were divorced (data not shown). By contrast, men rarely live alone with children, making up only 1.9 per cent of households in 2005.

Finally, in 2005 the residual category ‘other structures’ accounts for 7.8 per cent of households in the country, but for 14.9 per cent of the urban households. This is due to urban household heads and spouses accommodating relatives other than own children and parents more frequently than their rural counterparts. This category is even increasing, whereas the proportion of non-relatives and other relatives is actually declining slightly (Figure 4). This suggests a diversification of residence patterns with fewer non-relatives and other relatives being spread over more households over time.

MIPopLab data are better suited to studying changes over time, though in a relatively short time period. In MIPopLab as in the rest of the country, the nuclear structure dominates but to a lesser extent. A little less than half of the households are nuclear, 49.6 per cent on average between 2000 and 2006, in MIPopLab, compared to 61.1 per cent nationally and 51.1 per cent in urban areas according to DHS 2005 (Table 2). The main difference in household structure lies in the ‘extended’ category, which amounts to 23.6 per cent in MIPopLab (2000–06 average), compared to 15.6 per cent nationally and 18.8 per cent in urban areas (DHS 2005 data shown in Table 2). Most of the complex households in MIPopLab are downward-extended, and include children and children-in-law (about 57 per cent) and grandchildren (about 6 per cent) of the stem couple more often than parents and parents-in-law (less than 2 per cent, results not shown). MIPopLab data also reveal that 8.2 per cent of households are women living alone with children (compared to 11.9 per cent nationally), with about 70 per cent of these women being widowed and about 17 per cent divorced.

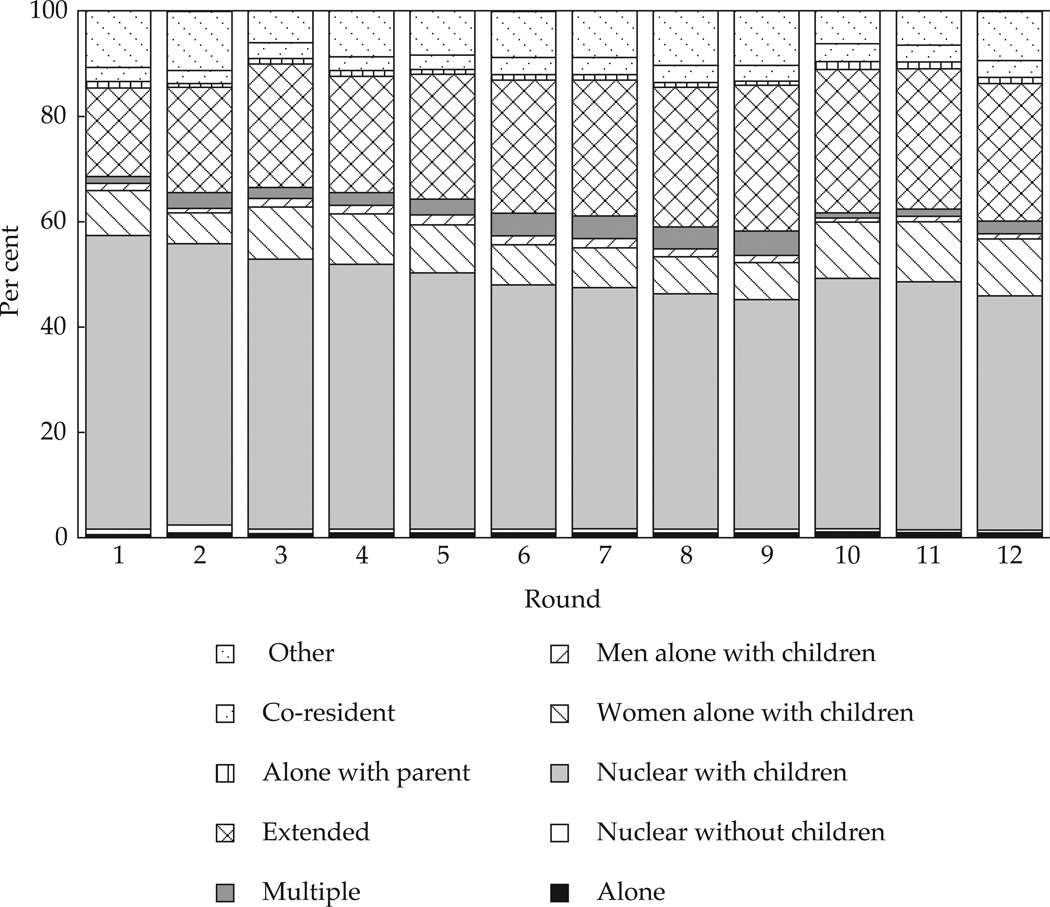

Figure 5 describes in more detail changes in MIPopLab household structures between 2000 and 2006. Several comparability issues must be noted first. One is that as the DSS was rolled in over time, all villages have had, by 2006, at least nine rounds, but only two had 10, and only one had all 12. This largely explains the discontinuity visible between Rounds 9 and 10. Moreover, the variables describing the relationships of household members were refined during the early rounds to provide a better categorization of households. The decline in the ‘other’ category from 10.8 per cent in Round 1 to 6.1 per cent in Round 3 reflects this gradual refinement of our categories. With these caveats in mind, it is best to focus on the trends from Rounds 3 to 9, of which the main one is the clear decline of nuclear-type households from 51.3 per cent to 43.6 per cent. The decline comes mostly from growth in extended-type households from 23.4 to 27.7 per cent, and other households from 6.1 to 10.4 per cent.

Figure 5. Households by structure categories, Cambodia, 2000–2006.

Source: Author’s calculations from MIPopLab data.

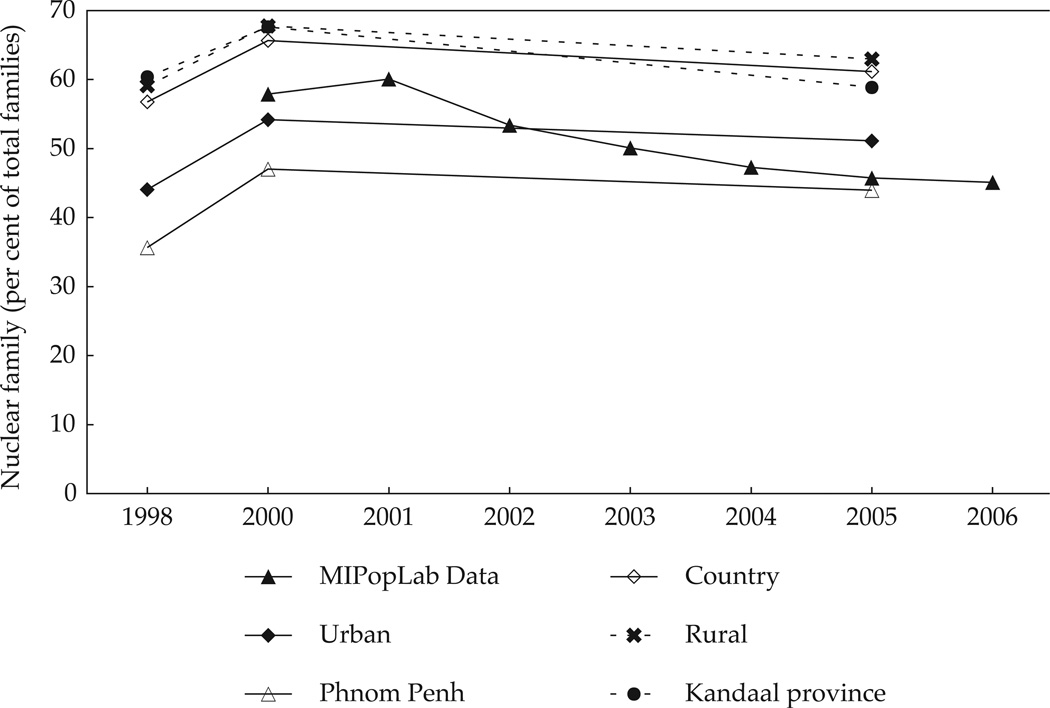

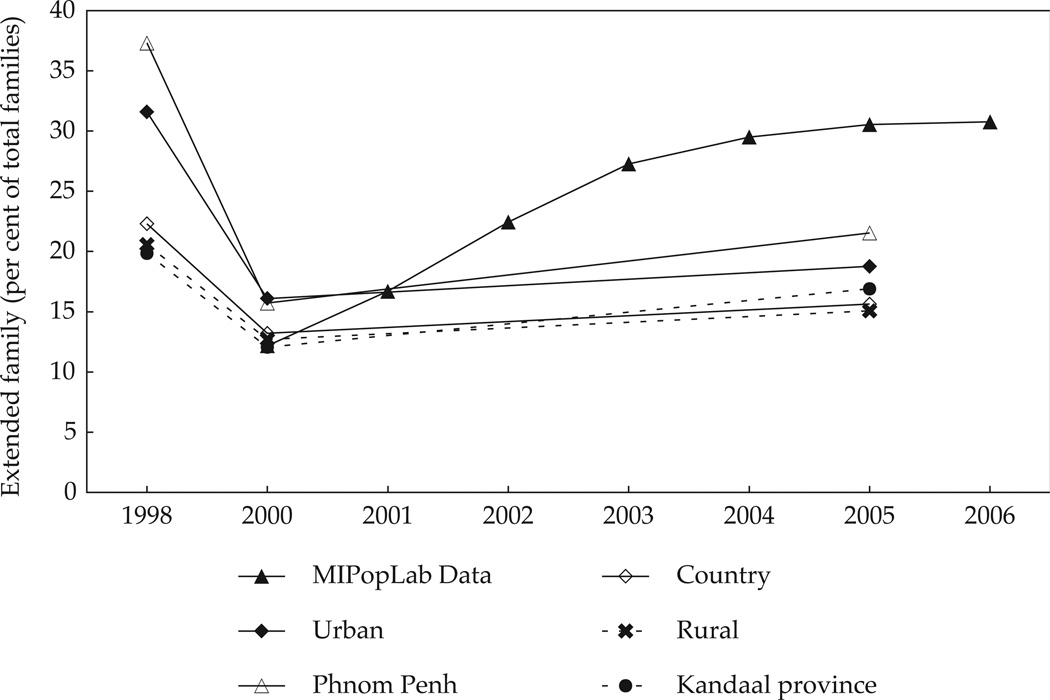

To locate MIPopLab trends in the national landscape, Figure 6 and Figure 7 show the same evolution from 1998 to 2006 for the populations of five different areas: (1) the villages followed up in MIPopLab, and for which data cover the whole 2000–2006 period; (2) the Phnom Penh Province (PPP), which was 56 per cent urban in 2005 and where the capital city is located; (3) the Kandal Province, which surrounds PPP and where MIPopLab is located; (4) all provinces but PPP combined; and (5) the whole country. MIPopLab longitudinal data are in close agreement with the provincial-and national-level trends in the other four populations. Changes over time can be tracked more precisely from the longitudinal data in MIPopLab, which suggest three main stages within the 1998–2006 period: (1) before 2001, when a reversal occurs; (2) between 2001 and 2003; and (3) after 2003, when a new plateau is observed.

Figure 6. Prevalence of nuclear families, five Cambodian populations, 1998–2006.

Sources: Authors’ calculations from MIPoPLab Data, the1998 Census, the 2000 and 2005 Cambodian DHS data files.

Figure 7. Prevalence of extended families, five Cambodian populations, 1998–2006.

Sources: Authors’ calculations from MIPoPLab Data, the1998 Census, the 2000 and 2005 Cambodian DHS data files.

For nuclear households, the prevalence increases during the first stage to a maximum of 60 per cent in 2001 (Figure 6). Changes occur at first in urban areas and their nearby rural areas as seen in PPP (as early as 1998, Figure 6) and MIPopLab (after 2001). These trends are reversed right after 2001. By 2002, the prevalence of nuclear households is already lower than its 2000 percentage: 53.4 per cent in 2002, compared to 57.9 per cent in 2000.

For extended households, the prevalence declines during the first stage. In MIPop-Lab, it reaches a minimum of 12.2 per cent in 2000 (Figure 7). Then, the prevalence of extended households rises dramatically to 30.8 per cent in 2006 (Figure 7). Further analysis of extended households in urban areas in 2005 suggests that these families are mainly downward extended (results not shown). They are composed of the head couple (26 per cent), typically grandparents, children of the head couple and their spouses (40 per cent), members of the third generation (21 per cent of grandchildren), and other relatives or non-relatives (10 per cent).

These comparisons do not suggest that trends in MIPopLab are unique. Figures for the MIPopLab villages are often intermediate between those for PPP and for the whole country. This is consistent with the urban-rural gradient we can observe from census data and the fact that MIPopLab is a rural area, but closer than rural areas except those in PPP to the capital city. Incidentally, a transition seems to take place about 2001 in the villages and the prevalence of nuclear households becomes closer to that of PPP than of Kandal Province. As noted earlier, the main distinctive feature of household distribution in MIPopLab is the prevalence of extended households which is higher (more than 30 per cent in 2005) than in other provinces, even PPP (21.5 per cent in 2005).

Individual trajectories

Using MIPopLab data, we can also relate these distributional trends to individual changes by following household members over survey rounds. Table 4 displays the household transition rate matrix in household structures between a given round and the following one six months later. The probabilities of a household remaining in the same category for six months are, as we could expect, relatively high (more than 70 per cent) regardless of the initial household structure, but ‘nuclear with children’ is the most stable structure. Indeed, the probability of a household remaining classified thus during the period 2000–2006 was 0.89. Remaining a lone-individual or in an extended household in the next round of the survey also has a 0.84 probability. The least stable household structures are the ‘other’ and ‘nuclear without children’ categories. For both, the most common transition is to become a ‘nuclear with children’ household by the next round (0.15 probability from nuclear without children and 0.12 probability for other households). While the first transition simply signals the arrival of a first child, the second one suggests that ‘other’ household structures may be temporary arrangements, such as for instance when a nuclear family takes in a distant relative or a non-relative.

Table 4.

Household-structure transition matrix, Cambodiaa

| Alone | Nuclear without child |

Nuclear with child |

Women alone with child |

Men alone with child |

Multiple | Extended | Alone with parent |

Co-resident | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | 0.84 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Nuclear without child |

0.01 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 |

| Nuclear with child |

0 | 0 | 0.89 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Women alone with child |

0.01 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.80 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 | 0.03 |

| Men alone with child |

0 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0 | 0.80 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 |

| Multiple | 0 | 0 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.75 | 0.11 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

| Extended | 0 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.84 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.04 |

| Alone with parent |

0.01 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.80 | 0 | 0.02 |

| Brothers/sisters co-resident |

0 | 0 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.79 | 0.05 |

| Other | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.69 |

a Rows indicate the household structure in which individuals lived in a given round n, and columns show the structure they lived in at the following round. Source: Author’s calculations from MIPopLab data.

Turning to individual life-course transitions, Table 5 describes the 10 most common sequences tracking individuals from Round 1 to Round 12. Perfect stability in all rounds is relatively rare, representing only 22 per cent of all individuals, mostly remaining in nuclear (19.4 per cent) or extended (2.7 per cent) households. Thus, 78 per cent of MIPopLab residents experienced at least one change in their living arrangements between 2000 and 2006. The most common transitions were from the nuclear to the extended structure or vice versa: 3.4 and 3.2 per cent, respectively.

Table 5.

Ten most frequent individual trajectories across household structure categories, Cambodia, 2000–2006

| Trajectories | Frequency | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilized → nuclear with child | 2,609 | 19.4 |

| Extended → nuclear with child | 458 | 3.4 |

| Nuclear with child → extended | 421 | 3.2 |

| Stabilized → extended | 365 | 2.7 |

| Other → nuclear with child | 276 | 2.1 |

| Women alone with child → nuclear with child | 159 | 1.2 |

Source: Author’s calculations from MIPopLab data.

In the next two tables, we study whether the individual transition patterns depend on having lost parents during the KR, and on gender. Although the KR attempted to destroy the institution of the family, there is strong evidence that it survived, and if the subsequent baby boom and low divorce rates are any indication, that KR survivors may have valued the nuclear family the most. The main finding from Table 6 is that individuals who experienced the loss of a parent during the KR regime are more likely to remain in a ‘nuclear with children’ household in all rounds: 13.5 per cent, compared to 9.8 per cent for individuals who lost their parents in a different period. When change occurred among individuals who lost a parent during the KR, it was most often towards a nuclear structure (9.5 per cent compared to 6.5 per cent for individuals who lost their parents in a different period), whereas the opposite is true concerning transition towards an extended structure (4.0 per cent and 8.2 per cent respectively).

Table 6.

Ten most frequent individual trajectories across household structure categories, by timing of parental death, miPoplab, Cambodia, 2000–2006

| Female trajectories | Frequency | Per cent | Male trajectories | Frequency | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stabilized → nuclear with child |

851 | 14.9 | Stabilized → nuclear with child |

908 | 17.0 |

| Extended → nuclear with child |

237 | 4.1 | Extended → nuclear with child |

268 | 5.0 |

| Other → nuclear with child |

224 | 3.9 | Other → nuclear with child |

173 | 3.2 |

| Women alone with child → nuclear with child |

171 | 3.0 | Nuclear with child → extended |

155 | 2.9 |

| Nuclear with child → extended |

138 | 2.4 | Stabilized → extended | 62 | 1.2 |

| Nuclear with child → women alone with child |

61 | 1.1 | Nuclear with child → men alone with child |

47 | 0.9 |

Source: Author’s calculations from MIPopLab data.

Gender differences (Table 7) are less dramatic since a large proportion of men and women live together in nuclear families, and stability in the nuclear family structure is the most common sequence both for men (17.0 per cent) and for women (14.9 per cent).

Table 7.

Ten most frequent individual trajectories across household structure categories, by sex, Cambodia, 2000–2006

| One/both parent(s) died but NOT under KR |

One/both parent(s) died under KR |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectories | Frequency | Per cent | Trajectories | Frequency | Per cent |

| Stabilized → nuclear with child |

112 | 9.8 | Stabilized → nuclear with child |

88 | 13.5 |

| Nuclear with child → extended |

53 | 4.6 | Nuclear with child → extended |

26 | 4.0 |

| Stabilized → extended | 45 | 3.9 | Stabilized → extended | 19 | 2.9 |

| Women alone with child → nuclear with child |

29 | 2.5 | Brothers/sisters co-resident → nuclear with child |

15 | 2.3 |

| Other → extended |

29 | 2.5 | Women alone with child → nuclear with child |

15 | 2.3 |

| Other → nuclear with child |

16 | 1.4 | Other → nuclear with child |

13 | 2.0 |

| Brothers/sisters co-resident → nuclear with child |

16 | 1.4 | Extended → nuclear with child |

10 | 1.5 |

| Extended → nuclear with child |

14 | 1.2 | Nuclear with child → other → nuclear with child |

9 | 1.4 |

| Women alone with child → extended |

13 | 1.1 | Alone → nuclear with child |

9 | 1.4 |

Sources: Author’s calculations from MIPopLab data.

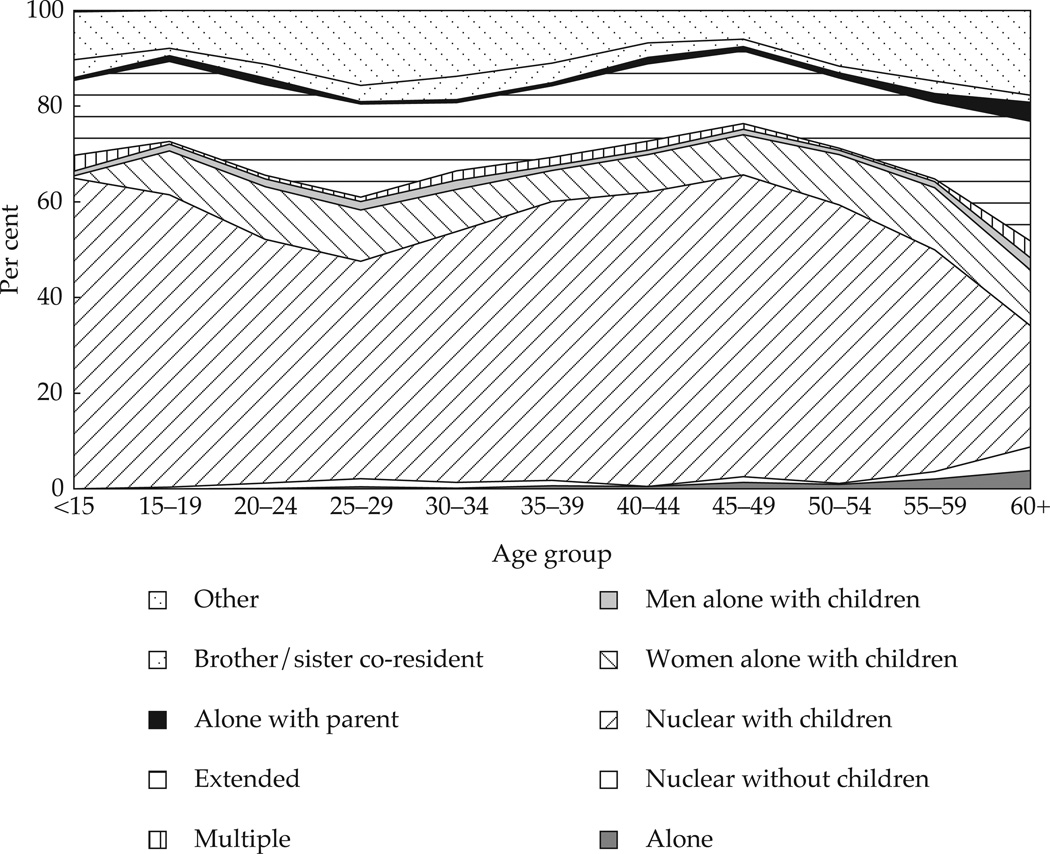

Finally, we study these transitions over the life course. Figure 8 shows four steps: (1) people under 20 years old, (2) people between 20 and 29; (3) people between 30 and 49; and (4) more than 50 years old. Given that SMAM is 24.6 for males and 22.8 for females (NIS 2004), the first stage, which represents a premarriage phase, is a period during which young people live mostly in a nuclear family with their parents. Extended living arrangements are most common in the second stage, when relatives in a more complex structure often take in young adults who wish to earn and save money, with marriage and having a family in mind. Additionally, young people who do not live with kin tend to live alone. The third stage, between 30 and 49 years of age, is a period when people live mostly in their new households in a nuclear structure again, as household head or spouse of the head. However, some unmarried women also live alone with their children. Finally, over age 50, when their children begin their own family cycle, MIPopLab residents most often live alone or with a child in an extended living arrangement.

Figure 8. Residence patterns over the life course, 2000–2006.

Source: Author’s calculations from MIPopLab data.

Kinship and solidarity networks

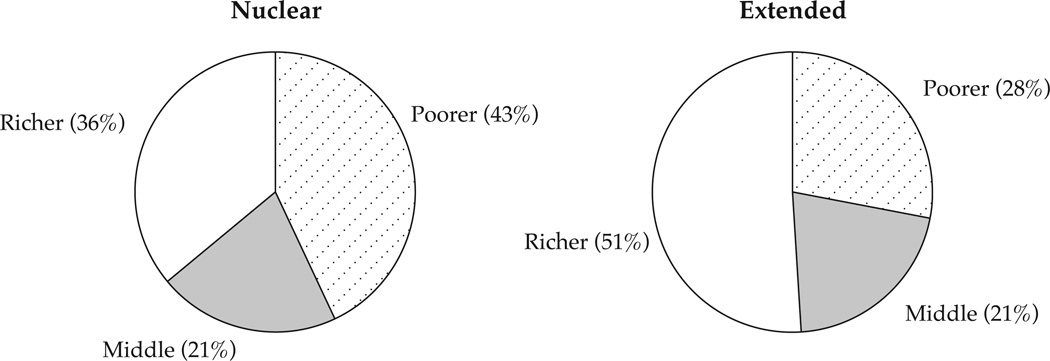

Describing household structure is relatively straightforward. Inter-individual support is not entirely confined to the household, but describing the contours of kinship and solidarity networks is more challenging. The CDHS 2000 and 2005 data suggest that nearly four-fifths of Cambodian families are close enough to easily visit their related kin in the space of a single day (78 per cent in 2000, and 80 per cent in 2005, results not shown). These data also demonstrate important differences in solidarity functioning between nuclear and extended households. Among households resorting to a family support network, 53 per cent were nuclear and 25 per cent were extended in 2000. The disparity is even increasing, with 65 per cent of households resorting to a family support network being nuclear and 12 per cent being extended in 2005. These differences appear to correspond to differences in wealth. Figure 9 shows a three-tier distribution of households based on the ‘Wealth Index’ for nuclear and extended households using the CDHS 2005 data. In 2005, as many as 48 per cent of nuclear households were found in the poorest third of Cambodian households. This explains in part a greater reliance on kin beyond the household’s confines, and greater need to borrow money from kin and non-kin. While only 10 per cent of extended households have debts in 2005, 65 per cent of nuclear households do. This evidence is consistent with Laslett’s (1988) argument about ‘nuclear hardship’.

Figure 9. Wealth distributions, nuclear and extended household structures, Cambodia, 2005.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the 2005 Cambodian DHS data files.

Discussion

From extant kinship studies, we expected the nuclear household to be the most prevalent type of household in contemporary Cambodia. According to these, a newly married couple may live with parents initially, but they are expected to form an independent household relatively soon when economically viable. Recent changes in the Cambodian economy, such as the development of the garment and tourism industry, or the housing and road construction boom for instance, should provide young adults with more opportunities to work toward those goals. One could thus expect nuclear households to be increasingly prevalent in this context of modernization, and average household size to be declining in most recent years.

We did find that nuclear households were quite prevalent in Cambodia, much more so than in Vietnam. The evidence regarding recent trends, however, is not entirely consistent with the above expectations. First, average household size remains high in Cambodia, about as high as in Thailand and in Vietnam around 1980. It may be tempting to attribute these differences in size to the lag in economic development between Cambodia and its neighbours, but trends over time suggest other factors are in play. The prevalence of nuclear households, which appears to have been increasing before 2000, has been declining in most recent years (2000–2005). Since the GPC 1998 and CDHS 2000 are not entirely comparable, caution is in order concerning the pre-2000 trends, but the longitudinal data from MIPopLab also suggest a lower level around years 2000 and 2001. Time series of economic growth rates show a similar inflection point around year 2001, with economic growth slowing between 2000 and 2002, and accelerating again after 2002 (Naron 2006). We estimate that the correlation coefficient between economic growth rate and the proportion of extended households was 0.82 between 2000 and 2006. The prevalence of extended families thus appears to increase when economic growth is faster, which challenges the family-pattern convergence theory (Goode 1963).

Urban-rural patterns shed light on this counter-intuitive finding. In spite of lower fertility, average household size is actually higher in urban than in rural areas. There are also proportionally fewer nuclear households in urban than in rural areas, in particular because urban households more often contain kin other than their own children and parents, as well as non-relatives. The prevalence of extended families increased during the recent fast-growth years, but so did the prevalence of other types of non-nuclear households, in particular these more complex households in urban areas. There has also been a surprising stability, at about one-eighth of all households, concerning the prevalence of households consisting of a mother alone with her children. With the decreasing weight of the generation of KR survivors, and widows in particular, the prevalence of those households should be declining, but on the other hand, divorce is on the rise (Heuveline and Poch 2006) and so is job-related physical separation.

We interpret these trends as signs of tensions during this transitional period in Cambodia. The norm toward independent living in nuclear households is confronted by harsh realities, especially in urban areas where the costs of establishing an independent household are higher than in rural areas. Thus, the increasing complexity of family forms and the concomitant declining prevalence of the ancestral nuclear structure appear to be adaptations to recent economic constraints. The nuclear hardship hypothesis (Laslett 1988) is supported by (1) the prevalence of the nuclear family system in the absence of national welfare institutions; (2) our results that nuclear households were more often poor than extended households and they more often relied on debt and assistance from other households; and (3) the strong ties that obviously exist between the nuclear families and their relatives living outside the household. Nevertheless, the temporalities of stressful circumstances in the family life course are crucial. For instance, the illness of a household adult worker when he is providing resources for his young children is much more jeopardizing than the onset of this illness a few years later, once the children have grown up. As noted above, anthropologists have long pointed at a great deal of pragmatism with respect to living arrangements in Cambodia (Ebihara 1968; Martel 1975; Ledgerwood 1995). This pragmatism is found today in high rates of mobility to adapt to increasing economic disparities across sectors. In 2005, while the Cambodian economy grew by over 13 per cent overall, the growth was four per cent in the agricultural sector, compared to 16 per cent for construction activities, 20 per cent for garment exports, and 24 per cent for tourism (Naron 2006). In high-growth years, disparities across sectors also increase and the agricultural sector, on which a majority of Cambodian households still depend for a living, becomes relatively less attractive. This fuels rural-to-urban migration, but many migrants cannot afford to live on their own at their urban destination and join an existing household. Job-related mobility may also contribute to the observed increase in family instability.

To conclude, recent trends in Cambodia are hard to explain with a broad modernization framework that would associate traditional societies with extended families and modern ones with nuclear families. It is likely that nuclear households have long been the norm in Cambodia, and our analysis of individual trajectories confirms that a nuclear living arrangement with parents and children constitutes the most steady structure. Rather than interpreting the recent decline in the prevalence of nuclear-family household as a fading of that norm, we believe this decline merely indicates a continued pragmatism with respect to living arrangements. Originating in a long history of adaptation to economic hardships, this pragmatism appears to prevent the formation of more nuclear households given the current conditions. Recent trends reflect this tension between normative choice toward establishing nuclear households, and economic constraints keeping adults in existing households. In recent years at least, modernization in Cambodia appears to have given more weight to the latter.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the support of the Ernst and Lucie Schmidheiny Foundation (CH-1211 Geneva) and the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University, where this article was written.

Footnotes

For more details on the DHS Wealth Index construction and methodology, see Rutstein and Johnson 2004.

Also called ‘nuclear’, ‘modern’, ‘primary’ or ‘conjugal’ family.

In the household questionnaire, the marital status of members is only available in CDHS 2005. This makes the exact Hammel and Laslett (1974) typology impossible to reproduce, since the latter includes a distinction between ‘extended’ and ‘multiple-generations’ households. For this reason, this paper uses a single, combined typological category and uses interchangeably the terms ‘extended’, ‘multiple’, ‘joint’ or even ‘stem’ family.

Children include those who are adopted or fostered.

Polygamy, which is not legal but continues to be mentioned in Cambodia, is very rarely reported in these surveys: for only 0.1 per cent of households in the 1998 census, 0.05 per cent in the CDHS 2000 and 0.07 per cent in the CDHS 2005.

We compared the structure in 2005 of households including all young children (recent fertility) with those only including children aged more than six in 2005.

We focus here on Cambodia and provide data for Vietnam as a counterpoint, but did not intend a thorough investigation of family dynamics in Vietnam.

Contributor Information

Floriane Demont, Laboratoire de démographie et d’études familiales (Population Studies Laboratory), University of Geneva.

Patrick Heuveline, Department of Sociology University of California.

References

- Antoine P, Bocquier P, Fall AS, Guisse YM, Nanitelamio J. Les familles Dakaroises face à la crise. Paris: ORSTOM, IFAN and CEPED (in French); 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts J. Household size and composition in the developing world in the 1990s. Population Studies. 2001;55(3):263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Burch TK. The size and structure of families: a comparative analysis of census data. American Sociological Review. 1967;32(3):347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Burch TK. Discussion Paper. London, Canada: No. 93–6, University of Western Ontario, Population Studies Center; 1993. Theories of household formation: progress and challenges. [Google Scholar]

- Das Gupta M. Lifeboat versus corporate ethic: social and demographic implications of stem and joint families. In: Fauve-Chamoux A, Ochiai E, editors. House and the Stem Family in EurAsian Perspective. Kyoto: International Research Centre for Japanese Studies; 1998. pp. 444–466. 12thInternational Economic History Congress. [Google Scholar]

- Derosas R, Oris M, editors. When Dad Died: Individuals and Families Coping with Distress in Past Societies. Bern: Peter Lang; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ebihara MM. New York: Svay, a Khmer village in Cambodia. Ph. D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Columbia University; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data or tears: an application to educational enrollment in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–132. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford D, Harris J. The extended African-American family. Urban League Review. 1991;14:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Goode W. World Revolution and Family Patterns. London: Free Press of Glencoe; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Goody J. Technology, Tradition and the State in Africa. London: Oxford University Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Goody J. The Expansive Moment: The Rise of Social Anthropology in Britain and Africa. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 1918–1970. [Google Scholar]

- Hammel EA, Laslett P. Comparing household structure over time and between cultures. Comparative Studies in Society and History. 1974;16:73–111. [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P. ‘Between one and three million’: towards the demographic reconstruction of a decade of Cambodian history (1970–79) Population Studies. 1998;52(1):49–65. doi: 10.1080/0032472031000150176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, Poch B. Do marriages forget their past? Marital stability in post-Khmer Rouge Cambodia. Demography. 2006;43(1):99–125. doi: 10.1353/dem.2006.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, Poch B. The phoenix population: demographic crisis and rebound in Cambodia. Demography. 2007;44(2):405–426. doi: 10.1353/dem.2007.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, Timberlake JM, Furstenberg FF., Jr Shifting child rearing to single mothers: results from 17 Western nations. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(1):47–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2003.00047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman C. Family and household structure in Vietnam: some glimpses from a recent survey. Pacific Affairs. 1996;69(2):229–249. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman C, Edwards J. Social change in Southeast Asia. In: Ritzer G, editor. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Vol. 9. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. pp. 4374–4380. [Google Scholar]

- Huguet J. The demographic situation in Cambodia. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 1992;6(4):79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan B. The Pol Pot Regime. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Knodel J, Kim SK, Zimmer Z, Puch S. Population Studies Center Research Report. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan; 2005. Older persons in Cambodia: a profle from the 2004 Survey of Elderly. 05–576. [Google Scholar]

- Laslett P. Family, kinship and collectivity as systems of support in pre-industrial Europe: a consideration of the ‘nuclear-hardship’ hypothesis. Continuity and Change. 1988;3(2):153–175. [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood JL. Khmer kinship: the matriliny/matriarchy myth. Journal of Anthropological Research. 1995;51(3):247–262. [Google Scholar]

- Lee GR. Comparative perspectives. In: Sussman MB, Steinmetz SK, Peterson GW, editors. Handbook of Marriage and the Family. Second edition. New York: Plenum Press; 1999. pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lingat R. Les régimes matrimoniaux du sud-est de l’Asie: essai de droit compare indochinois. Tome premier: les régimes traditionnels. Paris: Editions de Bocard and Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient (in French); 1952. [Google Scholar]

- Martel G. Lovea, village des environs d’Angkor: Aspects démographiques, économiques, et sociologiques du monde rural cambodgien dans la province de Siem-Réap. Paris: Ecole Française d’Extrême-Orient (in French); 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Mason KO. Family change and support of the elderly in Asia: what do we know? AsiaPacific Population Journal. 1992;7(3):13–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald P. Convergence or compromise in historical change? In: Ber-quó E, Xenos P, editors. Family System and Cultural Change. New York: Oxford University Press; 1992. pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Migozzi J. Cambodge: faits et problèmes de population. Paris: CNRS (in French); 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Naron HC. Cambodia’s Macroeconomic Developments in 2006. Phnom Penh: Secretary General Ministry of Economy and Finance, Supreme National Economic Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health (NIH) Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey, 2000. Phnom Penh and Calverton MD: National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health [Cambodia] and ORC Macro; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health (NIH) Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey, 2005. Phnom Penh and Calverton MD: National Institute of Statistics, Directorate General for Health [Cambodia] and ORC Macro; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics (NIS) General Census of Cambodia 1998: Analysis of Census Results, Report 1, Fertility and Mortality. Phnom Penh; 1999a. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics (NIS) General Population Census of Cambodia 1998. Phnom Penh; 1999b. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Statistics (NIS) Cambodia Inter–Censal Population Survey, Report 2, Phnom Penh Municipality. Phnom Penh; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Népote J. Parenté et organisation sociale dans le Cambodge moderne et contemporain. Geneva: Olizane SA (in French); 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ovesen J, Trankell I-B, Ojendal J. When Every Household Is an Island: Social Organization and Power Structures in Rural Cambodia. Vol. 15. Uppsala: Uppsala University; 1996. Uppsala Research Reports in Cultural Anthropology. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson JL, Hunter AG, Ensminger ME, Kellam SG. Black grandmothers in multigenerational households: diversity in family structure and parenting involvement in the Woodlawn community. Child Development. 1990;61:434–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02790.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilon M. Démographie des ménages et de la famille: application aux pays en développement. In: Caselli G, Vallin J, Wunsch G, editors. Démographie Analyse et Synthèse. Vol. VI. Paris: INED (in French); 2004. Chapter 90. [Google Scholar]

- Pran D, DePaul K, editors. Children of Cambodia’s Killing Fields: Memoirs by Survivors. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ram M, Wong R. Covariates of household extension in rural India: change over time. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1994;56:853–864. [Google Scholar]

- Rostow W. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Ruggles S. The effects of demographic change on multigenerational family structure: United States Whites, 1880–1980. In: Bideau A, et al., editors. Les chemins de la Recherche: les systèmes démographiques du passé. No. 32. Paris: coll. Recherche en sciences humaines (in French); 1996. pp. 21–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein SO, Johnson K. DHS Comparative Reports. ORC Macro: Calverton MD; 2004. The DHS Wealth Index. No. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Siampos GS. The population of Cambodia, 1945–1980. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. 1970;48(3):317–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliwinsky M. Le Génocide Khmer Rouge: Une Analyse Démographique. Paris: Editions L’Harmattan (in French); 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Smith HE. The Thai family: nuclear or extended. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1973;35(1):136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes C, LeClere FB, Yeu SH. Household extension and reproductive behavior in Taiwan. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1987;19:273–282. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000016928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd E. La diversité du monde: structures familiales et modernité. L’histoire immediate. Paris: Seuil (in French); 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tsui M. Changes in Chinese urban family structure. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:737–747. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision. New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Vimard P. Transition démographique et familiale: des théories de la modernisation aux modèles de crise. Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines (in French); 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy and Planning. 2006;21(6):459–468. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czl029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitz ED. A Century of Genocide: Utopias of Race and Nation. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]