Abstract

We report the social marketing strategies used for the design, recruitment and retention of participants in a community-based physical activity (PA) intervention, Madres para la Salud (Mothers for Health). The study example used to illustrate the use of social marketing is a 48-week prescribed walking program, Madres para la Salud (Mothers for Health), which tests a social support intervention to explore the effectiveness of a culturally specific program using ‘bouts’ of PA to effect the changes in body fat, fat tissue inflammation and postpartum depression symptoms in sedentary Hispanic women. Using the guidelines from the National Benchmark Criteria, we developed intervention, recruitment and retention strategies that reflect efforts to draw on community values, traditions and customs in intervention design, through partnership with community members. Most of the women enrolled in Madres para la Salud were born in Mexico, largely never or unemployed and resided among the highest crime neighborhoods with poor access to resources. We developed recruitment and retention strategies that characterized social marketing strategies that employed a culturally relevant, consumer driven and problem-specific design. Cost and benefit of program participation, consumer-derived motivation and segmentation strategies considered the development transition of the young Latinas as well as cultural and neighborhood barriers that impacted retention are described.

Keywords: social marketing, Hispanics, physical activity

INTRODUCTION

Established as a strategy to address social problems, social marketing reflects commercial-sector developed marketing technologies applied to the social problems that are resolved by behavior change (Andreasen, 1995; Gracia-Marco et al., 2011). Social marketing has been used in a variety of successful community healthy behavior change projects, and has been critically analyzed in recent reviews (Middlestadt et al., 1996; Quinn et al., 2010). The efficacy of social marketing has been examined with a wide range of benchmarked successes. For example, Gordon et al. (Gordon et al., 2006) assessed the evidence for social marketing in nutrition and physical activity (PA) behavior change showing increases in knowledge and ‘reasonable’ efficacy in influencing psychosocial variables. Most conclusions from reports that evaluated the efficacy of social marketing in behavior change interventions suggest that social marketing is effective in different target groups such as young people, minority ethnic and disadvantaged groups (Gordon et al., 2006).

The study example we use to illustrate the use of social marketing in recruitment, retention and implementation is a 48-week prescribed walking program, Madres para la Salud (Mothers for Health). Effective social marketing approaches are followed as suggested by the Social Marketing National Benchmark Criteria, which outlines elements of an intervention to determine whether it is consistent with social marketing (Gracia-Marco et al., 2011). These criteria include: (i) customer orientation: uses data obtained from different sources to develop a better understanding of the target audience, (ii) behavior: focuses on changing certain behaviors, (iii) theory: uses a theoretical framework to develop an intervention, (iv) methods mix: uses appropriate mix of methods in developing marketing strategies, (v) exchange: considers the costs and benefits incurred by the target group when changing the behavior, (vi) segmentation: uses a segmented approach, (vii) insight: focuses on consumer motivation and (viii) competition: assesses the barriers that discourage the acquisition of desired behaviors. Using the guidelines from the National Benchmark Criteria, we developed intervention, recruitment and retention strategies that reflect efforts to draw on community values, traditions and customs in intervention design, through partnership with community members (Kumpfer et al., 2004). We report the social marketing strategies used for the design, recruitment and retention of participants in a community-based PA intervention, Madres para la Salud (Mothers for Health).

MADRES OVERVIEW

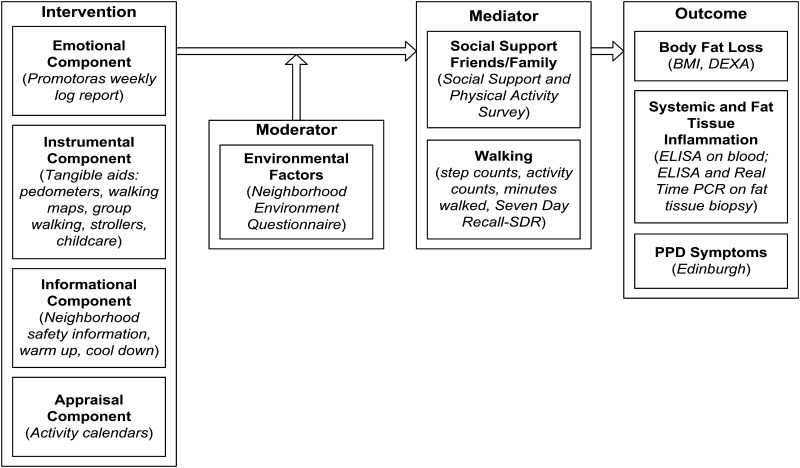

The Madres para la Salud (Mothers for Health) study tests a social support intervention to explore the effectiveness of a culturally specific program using a walking program to increase structured and lifestyle PA to effect changes in body fat, fat tissue inflammation and postpartum depression (PPD) symptoms in sedentary postpartum Hispanic women. The study aims were to (i) examine the effectiveness of Madres para la Salud for reducing distal outcomes in body fat systemic and fat tissue inflammation and PPD symptoms and (ii) test whether the theoretical mediators of social support and walking, and environmental factor moderators affect changes in body fat, systemic and fat tissue inflammation and PPD symptoms.

A sample of 177 sedentary Hispanic women, 18–35 years, and between 6 weeks and 6 months following childbirth were enrolled as study participants. Women were excluded if they engaged in regular, strenuous PA (exceeding 150 min of moderate-intensity PA weekly), had physical health problems that would preclude PA or were currently pregnant or planning on becoming pregnant within the next 12 months. The setting for recruitment in the study included community health clinics and the Hispanic women participant neighborhoods. Participants in the intervention group had weekly walking sessions and support interventions with Promotora, while participants in the attention-control group received health newsletters and follow-up phone calls. Data were gathered at baseline, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months using questionnaires assessing social support, neighborhood resources and a subset sample for DXA body scans as well as objective and self-report measures of walking adherence. Figure 1 illustrates the Madres Intervention Model.

Fig. 1:

Madres intervention model.

Objective measures of PAs included the ActiGraph GT1M accelerometer (Pensacola, FL) and the Omron HJ-720ITC pedometer (Shelton, CT). PA records (PA recalls) were kept from 3 to 7 days by participants to identify the types of PA behaviors performed during the same time accelerometers and pedometers were worn.

The Neighborhood Environment Questionnaire was used to assess the participants' perceptions of environmental safety, available resources for walking (Linné et al., 2003), and the social and cultural perceptions of participants related to their neighborhoods. Other neighborhood indices included information from the 2010 US Census data and the American Community Survey data, which were searched by both school districts served by the participants, by Census Tracts and zip codes. These data described the differential effects of neighborhood characteristics including density, access to health-care services, neighborhood spatial conditions and income, factors that contribute to cultural integration and opportunity for social mobility in Latinas.

Social support was assessed with two scales, social support and exercise survey, estimating perceived levels of support and the participation and involvement of others and the Medical Outcomes Study: Social Support Scale (Sherbourne and Stewart, 1991). Postpartum depression was measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale, a 10-item self-report measure of postpartum depression with 4-point Likert-type response options (0–3), with higher scores indicating more severe depression symptoms (Jadresic et al., 1995).

Body composition was assessed through bioelectric impedance (BIA), DXA examinations and fat distribution through waist–hip ratios. Two anthropometric measures (waist and hip circumference in centimeters) were taken on each participant. Dietary intake data were obtained using three unannounced 24-h recalls (24-R) using a five-step multiple pass method (Conway et al., 2003, 2004) by trained research assistants.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROBLEM OF WEIGHT MANAGEMENT AND CONTEXT IN HISPANIC WOMEN

Our first focus in the design and implementation of recruitment and retention strategies was to focus on the change of behaviors that address the ‘problem’ of obesity and its context among Hispanic women. Social marketing strategies suggest that the right kind of offering will stimulate consumers to act. The behaviors targeted in Madres para la Salud were threefold: enhancing social support, increasing PA and reducing body fat. Given that the weight gain accumulated throughout pregnancy is often retained throughout life, the management of weight is an important public health issue, particularly among young Hispanic women (Ogden et al., 2006).

The prevalence of overweight and obesity as well as their health implications disproportionately affect Hispanic women. National surveillance data from 2007 to 2008 indicate that 68.5% of Hispanic women aged 20–39 are overweight or obese (BMI >25), compared with 54.9% of non-Hispanic White women of the same age (Flegal et al., 2002). Community data of weight gain in young women suggest that childbearing may be an important contributor to the development of obesity in women, and is correlated with weight gained during gestation, number of births, prenatal PA, ethnicity and prepregnancy weight Further, excess weight gain during pregnancy and failure to lose weight after birth predicted long-term weight changes and higher BMIs in women up to a decade after childbirth (Rooney and Schauberger, 2002).

We predicated our theoretical approach and intervention design on strategies that we employed to better understand the cultural values of young Hispanic women who were our target population. The problem of weight change, obesity and PA in Hispanic women is best understood through factors that emphasize supportive relationships that integrate culture, the life/developmental transitions that impact the opportunity for PA, the built environment of the community and family-related factors.

For most women, lifestyle changes occur within the context of friends, family members, employment and social settings that contribute to the behavior change process (Barrera et al., 2006). Some research has indicated that the built environment contributes to healthy behaviors such as healthy eating and PA include safety, lighted streets, curbs, neighborhood food purchase accessibility and crime (Morland et al., 2002). Hispanics are shown to be more socioeconomically limited in their ability to live in or move to better neighborhoods than other groups (Sanchez-Vaznaugh et al., 2008) and living in more disadvantaged neighborhoods is associated with having greater BMI (Do et al., 2007). Overconsumption has been evidenced as a response to complex stressors during women's transitions. For example, comfort eating has been shown to be increased in obese women as a direct response to stress (Brogan and Hevey, 2009) and may accompany weight gain of pregnancy (Brogan and Hevey, 2009). Furthermore, the behavioral response to pregnancy is associated with contentment, a ‘letting oneself go,’ contributing to obesity and sedentary behavior (Ziebland et al., 2002). Further, overweight Hispanic women tend to become more sedentary with time, attributing non-participation in PA programs to dangerous neighborhoods, lack of childcare and lack of time (Gonzales and Keller, 2004).

DEFINING THE INTERVENTION FROM THE SALIENT THEORY

Madres para la Salud employed a theory-driven social support intervention program to promote the initiation and maintenance of regular PA, reduce body fat and modify fat distribution among postpartum Hispanic women. The operationalization of the social support concept in Hispanic women was specified from the literature, qualitative research and reviews of the intervention components by both an advisory board and Hispanic women from the target population. The ‘best’ product we developed, in conjunction with our community advisors and young postpartum Latinas, was a social-support walking intervention to manage weight. Our work indicated that social support for young Latinas was the most salient ‘delivery’ mechanism to facilitate the management of weight-addressing PA. Social support is the aid and assistance exchanged through social relationships and interpersonal transactions (Heany and Israel, 2002) Social support from family and friends has been consistently and positively related to PA (Keller et al., 2006). When social support is present, time spent in PA increased by 44% and the frequency of PA increases by 22% (Task Force on Community Preventive Services, 2007). In pregnant and postpartum Mexican-born Hispanic women, social support was viewed as essential to the maintenance of PA, especially when compared with women of other ethnic groups (Thornton et al., 2006). In data published by researchers in the Women's Cardiovascular Health Network, factors related to higher levels of PA among Hispanic women included knowing and observing others who engaged in PA (Eyler et al., 2003; Evenson et al., 2003; Voorhees and Rohm Young, 2003; Wilbur et al., 2003). Social support was the most commonly reported correlate to higher levels of PA for Hispanic women (Hovell et al., 1991; Eyler et al., 1999; Marquez et al., 2004; Barrera et al., 2006; Keller and Fleury, 2006). Recent focus group research that included Latinas from Texas shows that members of underserved populations are likely to respond to strategies that increase social support for PA and improve access to venues where women can be physically active (Van Duyn et al., 2007). Our research has further strengthened the rationale for social support as a theoretical and culturally proficient construct. We showed that Mexican American women in community health settings identified specific parameters contributing to walking locals, sociocultural resources used in walking and specific culture bound supports used in walking and PA (Keller and Trevino, 2001; Keller and Gonzales-Cantu, 2008). Thus, our product, Madres para la Salud, was developed using consistent and enduring consumer input from Hispanic women and integrated cultural values and patterns, and employed initiation and maintenance strategies of value to Hispanic women.

The intervention design for Madres para la Salud was based on a social support theoretical framework, defining social support as the extent and conditions under which ties are supportive. Operationalization of social support described the four sources of support: (i) emotional support: strategies to socialize within the walking cohorts, family and extended family, neighbors and groups; (ii) instrumental support: tangible support in the form of time and services, included the use of pedometers in monitoring regular walking, maps showing safe walking areas around participant neighborhood, walking groups, loaner baby strollers and walking shoes; (iii) informational support: facts, advice and education materials that were developed with and for the target audience to promote moderate-intensity walking, negotiate neighborhood safety and avoid musculoskeletal injury. Informational support was also operationalized through Promotoras who functioned as advocates to promote the safe performance of walking, building skills necessary for PA initiation and maintenance, for problem-solving and overcoming barriers to PA, and for monitoring progress in goal achievement and (iv) appraisal support: feedback through self-monitoring activities; women recorded their progress (pedometer step counts, number and duration of PA bouts) on weekly activity calendars.

RECRUITMENT

We developed extensive recruitment and promotional materials that were suggested and approved by the advisory groups, with Madres para la Salud, and included community partnerships. We circulated flyers at the Women Infant and Children clinics, elementary schools, community centers and churches and Hispanic Serving markets and discount stores. All materials were in Spanish; all of our research team is bilingual, bicultural and most of our participants spoke only Spanish.

Most of the women enrolled in Madres para la Salud were born in Mexico (n = 121), one was from Central America, 19 were born in the USA and 48% reported residing in the USA <10 years. The mean age of the women was 28.29 years (SD = 5.58), and 29 women (20.7%) reported that this was their first pregnancy, with the remainder (n = 111) having two to eight children (79.3%). Thirty-nine (27.9%) of the women had 1–2 children under the age of 2 at home and 51 (36.5%) had 1–2 children 3–5 years at home. One hundred six women (75.8%) cited that they were unemployed or never employed; 33 women were employed either full or part time (23.6%) and examples of employment included babysitter, cashier, cashier stocker, cook, medical interpreter, vegetable packing and waitress.

The Madres para la Salud marketing of the intervention not only included marketing with brochures, posters and formal media, but personal selling of the product among community partners. The cultural and customer preferences guided the integrated use of advertising, public relations, promotions and media advocacy. Most places and events allowed us to set up a recruitment table and circulate flyers and brochures. In partnership with our advisory board members, we sponsored tables at events such as the Maricopa Integrated Health System Women's Health Fair, Mountain Park Community Health Center Diabetes Prevention Health Fair, Maricopa County Department of Public Health Back to School Fair and the Central City South Community Connection Fair, sponsored by the city of Phoenix. Madres para la Salud was featured on Contacto Total, a weekday call-in radio program where project staff discussed the importance of PA for postpartum women and explained the warning signs of postpartum depression. Callers interested in the study were directed to call the research office to screen for eligibility. All study participants, interventionists and advisors have and wear Madres para la Salud t-shirts, pink sun visors and carry pink Madres para la Salud water bottles.

When our intervention was launched in Arizona, new immigration laws and enforcement implementation procedures were enacted. We quickly found out that the newly enacted laws impacted both undocumented immigrants as well as legal residents and they feared for their safety. Our target population became invisible and exceptionally difficult to reach. Thus, the sociopolitical environment became an important barrier to young Latina's efforts to engage in health-promoting activities that might ‘expose’ their presence to the public eye.

Our recruitment efforts became extraordinary, involving the gamut of resources, services and merchants available for young Latina mothers. These included the Women, Infant and Children Clinics, Head Start programs, elementary schools, health fairs, medical clinics, non-profit organizations, Young Men's Christian Associations, grocery stores and shopping areas with primarily Spanish-speaking merchants and neighborhood ministries. We placed recruitment advertisement on Spanish language radio stations.

MADRES PARA LA SALUD IMPLEMENTATION

The insight of customer motivation draws upon the investigator's knowledge of competing influences for achieving a direct influence on the desired behavior change (Wakefield et al., 2010). Program design strategies for Madres para la Salud were drawn from the literature in community-based health promotion, social marketing principles (i.e. 5-P's) as well as community members in the development of the intervention and recruitment strategies (Minkler and Wallerstein, 2004). Table 1 summarizes our efforts in implementing Madres para la Salud that targeted the inclusion of cultural and contextually relevant strategies to promote social support and PA among Hispanic women. We informed Madres para la Salud by developing and implementing an advisory group of young Latinas with new infants to inform us on consumer motivation. The women in the advisory group served to elicit the experiences of women related to PA, to craft adherence and motivation strategies and share the experiences of young Latinas who lived in neighborhoods where our walking interventions take place for safety, motivation from partners, family and spouses and guiding participant-driven sampling to enhance study participation. Several strategies for PA and weight management motivation were elicited from advisory group members: participation incentives that identified women as part of a program; incentives that targeted the women, and women's children among young Latinas, such as baby wipes, pacifiers, loaned strollers, beauty products and small household items, such as scented candles and competitive incentives for goal achievement.

Table 1:

Social marketing conceptual and segmenting strategies

| Social marketing concept | Study component | Segmenting and tailoring |

|---|---|---|

| Product | Madres para la Salud intervention activities for a moderate-intensity walking intervention | Development of strategies for sources of support and family involvement |

| Inclusion of cultural values that impacted traditional roles for Hispanic women | ||

| Inclusion of time management strategies to maintain ‘bouts’ of walking that coincide with family activities | ||

| Place | Walking in community neighborhoods and identification of routes in safe areas | Identification of telephone trees and procedures to avoid immigration sweeps |

| Identification of specific safety alerts for age group, for example not texting or listening to I tunes while walking in unsafe neighborhoods | ||

| Price | Options for 150 min/week walking duration:

|

Child care responsibilities shared among walkers |

| Strollers to walk with babies | ||

| Social support for walking from participants, neighbors, family | ||

| Promotion | Circulate and flyers at the Women Infant and Children clinics, elementary schools, community centers and churches and Hispanic Serving markets and discount stores | All recruitment materials in Spanish |

| All of our research team is bilingual, bicultural; most of our participants speak only Spanish | ||

| Incentives that address family needs for low-income women: such as baby clothes, kitchen items, bus chits, movie tickets | ||

| Partnerships | Advisory group of young Latinas with new infants: | Walking groups based at community health clinics where women received prenatal care |

| Promatoras |

The development of the culturally relevant design and implementation strategies of Madres para la Salud followed an iterative process, with the goals of designing a program that would be scientifically sound as well as culturally relevant and meaningful to Hispanic women in urban Southwest neighborhoods. Further, the ‘problem’ of weight management was amenable to social marketing strategies and was well documented in the targeted cultural subgroup. Following our reviews of social support strategies used with Hispanic women, certain influences that hallmark distinct cultural preferences became apparent: family responsibilities, including childcare, were exceptionally important. Childbearing age Hispanic women often had to work, manage a home and organize children's activities so that instrumental supports for PA were imperative. The notion of time management was also an exceptional issue; Hispanic women were most interested in engaging in PA, but found it difficult to negotiate on a daily basis. Last, Hispanic women expressed concern with male–female cultural role restrictions.

The place of our product, or intervention delivery was an important consideration. The setting for the implementation of Madres para la Salud was assessed through community data of the five zip codes where our study participants reside. These data showed that 81.6% of residents were Hispanic or Latino, 25.3% of residents 25 and over had <9th grade education, 38% were foreign born, and of those who are foreign born, 87.2% were not USA citizens. Within the five zip codes 28.5% of all families with children under the age of 18 had income below the federal poverty level and 37.1% of female head of household families had income below the federal poverty. Quality of neighborhood life was assessed for outdoor quality for walking, noting that crime reports indicated that among reported crimes in the community, our women's neighborhoods were cited as highest in the city for domestic violence-related crime incidents, homicides and robberies, aggravated assaults, drug crimes and total violent crimes. These neighborhoods were second highest in the city for sexual assaults, total property crimes, calls for service to city's Police Department, and gang involved incidents. Thus, the place of the intervention was important to assure accessibility and safety for the participants to engage in PA.

We implement the walking groups in the women's neighborhoods. Each walking route was mapped for physical safety, and we developed ‘history talks’ of the neighborhoods to stimulate interest in the surroundings. Intervention (social support) delivery was driven by women's schedules, on occasion delivered one: one if women had multiple scheduling conflicts, and regularly at neighborhood centers, churches, schools and ministries. Local resource for walking safely with children and the group was a major intervention component (informational support) and was included in manipulation checks to determine the intervention impact. Our manipulation checks were both a formal and informal method to ascertain that the intervention was received and enacted by the women. The Promotoras kept written field notes documenting which aspect of social support the women used to maintain PA, and the women completed a written survey describing each social support element (e.g. appraisal support) they used following the intervention delivery.

Social marketers recognize that the product use is based on the consideration of both benefit and cost, or the price of the product. Our formative work showed that women carefully weighed participation in a PA program against the responsibilities of family life. A primary concern was to minimize the cost of participating in the intervention, while enhancing the benefits to women in the community. For many women, sustained participation was thought to be difficult, given family, financial, work and transportation constraints as well as traditional values that may not support PA. Social marketers also recognize the importance of the product's accessibility. Madres para la Salud advisory Latinas described the ways that the PA program might reach women in the community. Women spoke of lack of access to health and fitness opportunities.

Weighing the benefits of the cost of participating in a moderate intensity walking program against the perceived time constraints of multiple roles and family obligations, we focused on creating strategies where the study participants would perceive the benefits of the program over the costs. Specific strategies to manage time were developed for young Hispanic women, and these coincided with routines of work, household chores and childcare. For Hispanic women, informational support was developed as specific time-management planning, helping women to carve out planned times for walking and anticipating planned family care resources to use. Further planning included strategizing planned walking sessions that are family centric. Planned times to walk children to and from school, planned walking to the market and walking in place at home when no childcare is available are specific strategies.

We included incentives and rewards as promotional components for accomplishing behavioral strategies that are in the theoretical social support components of Madres para la Salud. With the consumer advisors, we developed an aqua and pink Madonna figure leaning over a baby buggy logo which used in tee-shirts and post-card alerts that have the word ‘free’ prominently displayed. Women have opportunities to draw aqua or pink items with goal setting accomplishments, such as baby booties, hats, gloves, kitchen gadgets and cosmetics. For each woman in the intervention group, a pink photo album is provided, and each week photographs of her and the children who accompany her on the walks are given to them for the albums.

SEGMENTATION

Two significant areas of focus were developed that augmented the critical inputs of the Madres social support intervention Hispanic women: (i) the strategies developed for sources of support and family involvement and (2) the cultural values that impacted traditional roles for Hispanic women.

Strategies developed for sources of support and family involvement

For our young Hispanic women, the support of family was a very important resource that influenced attitude and commitment to PA. Hispanic women valued their role as mother and as caregiver, and felt they needed to stay healthy and able to care for their children and husbands, and participate actively in their lives. However, for some Hispanic women, their role of caregiver and provider for the family often had a negative impact on the time available to perform structured PA. Women shared stories of multiple jobs, the ongoing needs of children and caring for the home. While PA was increased through household chores and care-giving activities, women often felt torn between the need to care for themselves and the needs of others.

Cultural values that impacted traditional roles for Hispanic women

Young Hispanic women noted that expectations often included a cultural aspect that further limited participation in PA. For some women, spouses were a significant barrier to PA due to traditional cultural attitudes which encouraged women to focus on caring for their home and children, rather than taking time for themselves. For young Hispanic women, new mothers and new mothers with small children, social support was quite specific. Instrumental support was strategized as providing specific safe resources for childcare while walking. For young Hispanic women, a strong motivating factor for walking to augment postpartum weight was the physical attractiveness desired to continue their self-image and remain attractive for their partner or spouse.

The cultural values of machismo and marianismo were specifically strategized in the intervention protocol, using open discussions of these ‘traditional’ male–female values and subsequent role enactments as well as engaging in dialogs that addressed ways to engage in walking that worked with these roles. The aspects of traditional machismo were discussed (Torres et al., 2002) and the women explored the important characteristics of a machista: responsibility for family welfare, protection of the family and competition. Young Hispanic women were encouraged to explore and employ specific strategies that emphasized the husband/partner's family leadership as protector of family health and ways to sustain health through walking/exercise. One woman employed the strategy of seeking the wives/girlfriends of her husband's friends to serve as her walking support group. Women learned how marianismo and the traditional role of serving the family's needs (even to the detriment of their own physical and emotional health) could be a barrier to PA. Promotoras discussed how carving out daily time for PA is a way to care for family and self. We emphasized: ‘if mom is healthy, the family will be healthy.’

RETENTION

Retention of these ‘hard-to-reach’ participants was often problematic and was particularly problematic in our study due to difficulty with the local political environment necessitating women seeking to remain ‘hidden’ in public places. Retention strategies included the use of tracking cards, updated during weekly contacts, the use of very needed incentives such as bus transportation chits, study equipment ‘gifted’ in incentive raffles such as pedometers, walking shoes and baby strollers. To help retain women in the study, our Promotoras use two activities: (i) they use telephone trees to alert women to immigration and arrest ‘sweeps’ that occur (public notice is released by the sheriff's department) and (ii) neighborhood resources are maximized to assist women in maintaining their walking by using areas that do not coincide with law enforcement's planned activities or those that are located in hard-to-reach areas, such as along a neighborhood's many irrigation canals.

While we expected close to 50% dropout, we have experienced a 33% dropout. However, the dropout rate was higher in the intervention group compared with the control group (45.08 vs. 20.59%). Of the 32 women in the intervention group who dropped from the study, the highest reasons given for dropout were: could not comply with the 150 min per week moderate intensity walking requirement (n = 6), refused to answer (n = 6), lack of time (n = 5) and moved out of state (n = 4). Only four women in the intervention group dropped due to a new pregnancy during the 48-week intervention, which was less than expected.

The dropout rate was considerably lower in the control group and the participants in this group were required to meet with study staff just three times during the study for data collection. Of the 14 women who dropped from the control group, the reasons listed were: moved out of state (n = 5), pregnant (n = 4), refused to answer (n = 3) and unable to contact (n = 2). If the study staff had difficulty getting the women in the intervention group to comply with the data collection, they would offer to complete their data collection at their home, work, in the evenings or on the weekends.

As shown in Table 2, attrition was highest at the beginning of the study and tailored off considerably between the fourth and fifth data collection. Between the baseline and second data collection, 23 women had already dropped from the control group. Therefore, when it became too burdensome for some working mothers to attend the group intervention sessions, the Pomotoras met with some participants individually after work or on the weekend at a local YMCA, neighborhood park or the participant's home. In addition, onsite childcare was provided by study staff for the walking group sessions during the 48-week intervention, for example at YMCAs where participants walked on treadmills and could not push their children in strollers.

Table 2:

Retention for Madres para la Salud

| Time point | Total sample | Intervention group | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 139 | 71 | 68 |

| Time 2 | 112 | 48 | 64 |

| Time 3 | 99 | 42 | 57 |

| Time 4 | 97 | 40 | 57 |

| Time 5 | 93 | 39 | 54 |

CONCLUSIONS

Behavior change, such as the initiation and sustaining walking to improve weight management, occurs under circumstances that are influenced by marketing approaches, and these approaches are most effective when segmented groups are used, more salient in diverse and somewhat stigmatized groups (Dearing et al., 1996; Gregson et al., 2001). Our efforts in the design, recruitment, retention and implementation of Madres para la Salud integrated all aspects of benchmark criteria for social marketing, and demonstrate the effectiveness of such marketing procedures in recruitment and retention strategies to the cultural and contextual needs of Hispanic women.

FUNDING

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research NIH/NINR 1 R01NR010356-01A2, Madres para la Salud (Mothers for Health). The study protocol was approved by the Arizona State University Institutional Review Board and the Maricopa Integrated Health System Human Subjects Review Board. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Phoenix VA Health Care System.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The contents do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

REFERENCES

- Andreasen A. R. Marketing Social Change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M., Jr, Toobert D. J., Angell K. L., Glasgow R. E., Mackinnon D. P. Social support and social-ecological resources as mediators of lifestyle intervention effects for type 2 diabetes. Journal of Health Psychology. 2006;11:483–495. doi: 10.1177/1359105306063321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brogan A., Hevey D. The structure of the causal attribution belief network of patients with obesity. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2009;14:35–48. doi: 10.1348/135910708X292788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway J., Ingwersen L., Vinyard B., Moshfegh A. Effectiveness of the US Department of Agriculture 5-step multiple-pass method in assessing food intake in obese and non-obese women. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003;77:1171–1178. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway J., Ingwersen L., Moshfegh A. Accuracy of dietary recall using the USDA five-step multiple-pass method in men: and observational validation study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing J. W., Rogers E. M., Meyer G., Casey M. K., Rao N., Campo S., et al. Social marketing and diffusion-based strategies for communicating with unique populations: HIV prevention in San Francisco. Journal of Health Communication. 1996;1:343–363. doi: 10.1080/108107396127997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do D. P., Dubowitz T., Bird C. E., Lurie N., Escarce J. J., Finch B. K. Neighborhood context and ethnicity differences in body mass index: a multilevel analysis using the NHANES III survey (1988–1994) Economics and Human Biology. 2007;5:179–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenson K. R., Sarmiento O. L., Tawney K. W., Macon M. L., Ammerman A. S. Personal, social, and environmental correlates of physical activity in North Carolina Latina immigrants. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25(3 Suppl. 1):77–85. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00168-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler A. A., Brownson R. C., Donatelle R. J., King A. C., Brown D., Sallis J. F. Physical activity social support and middle- and older-aged minority women: results from a US survey. Social Science & Medicine. 1999;49:781–789. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyler A. A., Matson-Koffman D., Rohm Young D., Wilcox S., Wilbur J., Thompson J. L., et al. Quantitative study of correlates of physical activity in women from diverse racial/ethnic groups: women's cardiovascular health network project—introduction and methodology. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25(3 Suppl. 1):5–14. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal K. M., Carroll M. D., Ogden C. L., Johnson C. L. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1723–1727. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.14.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales A., Keller C. Mi familia viene primero (my family comes first): physical activity issues in older Mexican American women. Southern Online Journal of Nursing Research. 2004;5:21. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon R., McDermott L., Stead M., Angus K. The effectiveness of social marketing interventions for health improvement: what's the evidence? Public Health. 2006;120:1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracia-Marco L., Vincente-Rodriguez G., Borys J. M., Lebodo Y., Pettigrew S., Moreno L. A. Contribution of social marketing strategies to community-based obesity prevention programmes in children. International Journal of Obesity. 2011;35:472–479. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregson J., Foerster S. B., Orr R., Jones L., Benedict J., Clarke B., et al. System, environmental, and policy changes: using the social-ecological model as a framework for evaluating nutrition education and social marketing programs with low-income audiences. Journal of Nutrition Education. 2001;33(Suppl. 1):S4–15. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heany C. A., Israel B. A. Social networks and social support. In: Glanz K., Rimer B. K., Lewis F. M., editors. Health behavior and health education: theory, research and practice. 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hovell M., Sallis J., Hofstetter R., Barrington E., Hackley M., Elder J., et al. Identification of correlates of physical activity among Latino adults. Journal of Community Health. 1991;16:23–36. doi: 10.1007/BF01340466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jadresic E., Araya R., Jara C. Validation of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) in Chilean postpartum women. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1995;16:187–191. doi: 10.3109/01674829509024468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C., Fleury J. Factors related to physical activity in Hispanic women. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006;21:142–145. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200603000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C., Gonzales-Cantu A. Camina por salud: walking in Mexican American women. Applied Nursing Research. 2008;21:110. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C., Trevino R. P. Effects of two frequencies of walking on cardiovascular risk factor reduction in Mexican American women. Research in Nursing & Health. 2001;24:390–401. doi: 10.1002/nur.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller C., Allan J., Tinkle M. B. Stages of change, processes of change, and social support for exercise and weight gain in postpartum women. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2006;35:232–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2006.00030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpfer K. L., Alvarado R., Smith P., Bellamy N. Cultural sensitivity and adaptation in family-based prevention interventions. Prevention Science. 2004;3:241–246. doi: 10.1023/a:1019902902119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linné Y. Y., Dye L. L., Barkeling B. B., Rössner S. S. Weight development over time in parous women-The SPAWN study-15 years follow-up. International Journal Of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders. 2003;27:1516–1522. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez D. X., McAuley E., Overman N. Psychosocial correlates and outcomes of physical activity among Latinos: a review. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:195–229. [Google Scholar]

- Middlestadt S. E., Bhattacharyya K., Rosenbaum J., Fishbein M., Shepherd M. The use of theory based semistructured elicitation questionnaires: formative research for CDC's prevention marketing initiative. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1974) 1996;111(Suppl. 1):18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M., Wallerstein N. Improving health through community resources. In: Minkler M., editor. Community Organizing and Community Building for Health. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2004. pp. 30–52. [Google Scholar]

- Morland K., Wing S., Diez Roux A. The contextual effect of the local food environment on residents’ diets: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1761–1767. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden C. L., Carroll M. D., Curtin L. R., McDowell M. A., Tabak C. J., Flegal K. M. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the united states, 1999–2004. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn G. P., Ellery J., Thomas K. B., Marshall R. Developing a common language for using social marketing: an analysis of public health literature. Health Marketing Quarterly. 2010;27:334–353. doi: 10.1080/07359683.2010.519989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooney B. L., Schauberger C. W. Excess pregnancy weight gain and long-term obesity: One decade later. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;100:245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02125-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vaznaugh E. V., Kawachi I., Subramanian S. V., Sanchez B. N., Acevedo-Garcia D. Differential effect of birthplace and length of residence on body mass index (BMI) by education, gender and race/ethnicity. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 2008;67:1300–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne C., Stewart A. The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Task Force on Community Preventive Services. 2005. The guide to community preventive services (community guide). http://www.thecommunityguide.org/index.html. (13 September 2012, date last accessed)

- Thornton P. L., Kieffer E. C., Salabarria-Pena Y., Odoms-Young A., Willis S. K., Kim H., et al. Weight, diet, and physical activity-related beliefs and practices among pregnant and postpartum Latino women: the role of social support. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2006;10:95–104. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-0025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres J. B., Solberg V. S. H., Carlstrom A. H. The myth of sameness among Latino men and their machismo. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72:163–181. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Duyn M. A., McCrae T., Wingrove B. K., Henderson K. M., Boyd J. K., Kagawa-Singer M., et al. Adapting evidence-based strategies to increase physical activity among African Americans, Hispanics, Hmong, and native Hawaiians: a social marketing approach. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4:A102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees C. C., Rohm Young D. Personal, social, and physical environmental correlates of physical activity levels in urban Latinas. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25(3 Suppl. 1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield M. A., Loken B., Hornik R. C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet. 2010;376:1261–1271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60809-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur J., Chandler P. J., Dancy B., Lee H. Correlates of physical activity in urban Midwestern Latinas. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2003;25(3 Suppl. 1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziebland S., Robertson J., Jay J., Neil A. Body image and weight change in middle age: a qualitative study. International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders: Journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2002;26:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]