Summary

We investigated the effect of modern radiation techniques on pulmonary function in non-small cell lung cancer patients. We found that lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is reduced in the majority of patients after radiation. Moreover, we found that multiple factors, including pretreatment DLCO ≤50% and lung and heart dosimetric data >median were associated with larger posttreatment declines in DLCO.

Purpose

Definitive radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) adversely affects pulmonary function. However, the extent of these effects after radiation delivered with modern techniques is not well known.

Methods and Materials

We analyzed 250 patients who had received ≥60 Gy radio(chemo)therapy, for primary NSCLC in 1998-2010 and had undergone pulmonary function tests (PFTs) before and within one year after treatment. Ninety three patients were treated with 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy, 97 with intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), and 60 with proton beam therapy (PBT). Post-radiation PFT values were evaluated amongst individual patients compared to the same patient's pre-radiation value at the following time intervals: 0 to 4 (T1), 5 to 8 (T2), and 9 to 12 (T3) months.

Results

Lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) is reduced in the majority of patients along the 3 time periods after radiation, whereas the forced expiratory volume in 1 second per unit of vital capacity (FEV1/VC) showed an increase and decrease after radiation in a similar percentage of patients. There were baseline differences (stage, RT dose, concurrent chemotherapy) among the radiation technology groups. On multivariate analysis, the following features were associated with larger posttreatment declines in DLCO: pretreatment DLCO, gross tumor volume (GTV), lung and heart dosimetric data, and total radiation dose. Only pretreatment DLCO was associated with larger posttreatment declines in FEV1/VC.

Conclusions

DLCO is reduced in the majority of the patients after radiotherapy with modern techniques. Multiple factors, including GTV, pre-radiation lung function and dosimetric parameters, are associated with the DLCO decline. Prospective studies are needed to better understand whether new radiation technology such as PBT or IMRT may decrease the pulmonary impairment through greater lung sparing.

Keywords: non–small cell lung cancer, radiation therapy, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide, pulmonary function

Introduction

Thoracic radiotherapy (RT) is associated with significant alterations in lung function as assessed by objective pulmonary function tests (PFTs) [1, 2]. The extent of residual lung function is a major determinant of a patient's functional status after treatment. Studies at our institution [3] and others [1, 4] have shown that the largest and most consistent changes in PFT values after definitive RT for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) occur in the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). The decrease in DLCO has also been directly associated with respiratory morbidity [1, 4].

Novel RT techniques such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), four-dimensional computed tomography (4D CT) –based treatment planning, and proton beam radiotherapy (PBT) have been shown to deliver lower doses to critical normal structures than older techniques [5]. However, the translation of dosimetric superiority to clinical advantages such as long-term respiratory function is still being established.

We performed this study to investigate the extent of change in pulmonary function over time after definitive RT with modern techniques and to identify predictors of changes in pulmonary function based on patient, tumor, and treatment characteristics.

Patients and Methods

Patient selection criteria

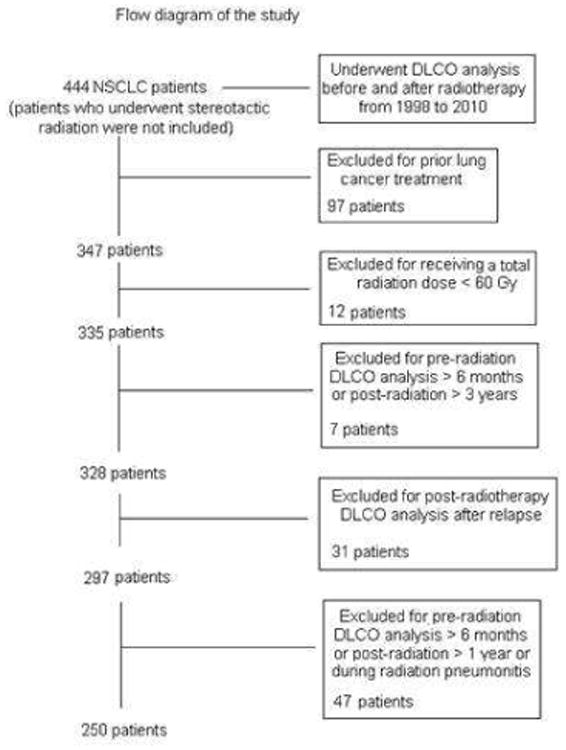

This retrospective analysis was approved by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center institutional review board and was in compliance with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations. Patients had a primary diagnosis of NSCLC and were treated with RT at MD Anderson from November 1998 to October 2010 and DLCO analyses before and after RT. Figure 1 illustrates the patient selection process. Patients who underwent postradiation PFT analysis after locoregional or distant relapse were excluded to avoid introducing confounding factors related to recurrent disease or salvage therapy. In addition, we did not analyze PFTs during the active period of symptomatic pneumonitis (grades ≥2) in order to avoid introducing confounding factors related to the treatment, with “active” being defined as between 1 month prior to the diagnosis of radiation pneumonitis and 2 months afterwards. Ultimately, 250 patients met the selection criteria for this study; 93 of them had been treated with 3DCRT, 97 with IMRT, and 60 with PBT. Three-dimensional conformal therapy was started at our institution in 1997-1998 [5-7]. The transition from 3DCRT to IMRT occurred in 2004, and PBT has been used after 2005. Only patients treated with involved field radiotherapy were included in this study. Complete dosimetric data (including mean lung dose [MLD], volume of normal lung receiving 5 Gy or more [lung V5], lung V20, mean heart dose [MHD], volume of normal heart receiving 40 Gy or more [heart V40]) and gross tumor volume (GTV) were available for 235 patients (94%). Data on previous respiratory or cardiovascular disease were collected for all patients.

Fig. 1.

Cohort selection. NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide.

Pulmonary function tests

The two characteristics of pulmonary function that were the focus of this study were diffusing capacity and obstruction. On the basis of the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society recommendations [8], the DLCO (percentage of predicted value) was used as a measure of diffusion capacity and the forced expiratory volume in 1 second per unit of vital capacity (FEV1/VC) was used as a measure of obstruction. All patients included in this study had undergone both evaluations.

Study endpoints and follow-up

Stata/SE 11.1 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas) was used for data analyses. Post-radiation PFT values (percentage of predicted) were evaluated amongst individual patients compared to the same patient's pre-radiation value at the following time intervals: 0 to 4 (T1), 5 to 8 (T2), and 9 to 12 (T3) months. In patients that had more than one post-treatment PFT value within a time period, the lowest value within that time period was used for analysis and compared to the baseline value. Each time period was used for analysis and compared to the individual's baseline value. We used the linear regression model for the PFT evaluation at different time intervals. Additionally, we used the logistic regression model to evaluate predictors of major changes in pulmonary function after RT (DLCO or FEV1/VC decrement greater than the upper tertile).

Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to evaluate the effects of radiation fractionation, use of chemotherapy, patient factors (age, sex, smoking habits, Karnofsky performance status, and respiratory and cardiovascular comorbidities), tumor factors (stage and GTV), treatment factors (technique and dosimetric variables), and pretreatment PFT values. Medians were used as cut-off values for the dosimetric data. In multivariate analysis, the dosimetric variables were assessed in the model separately (lung V5, lung V20, heart V40, MHD, MLD) due to the high correlation with each other.

Results

Patient characteristics, treatment characteristics, and dosimetric information for all three treatment groups are shown in Table 1. All patients had good performance status (Karnofsky performance score ≥70) and underwent RT 5 days a week to a total dose of 60-87.5 Gy/GyEquivalent[E] (median 69.6 Gy/GyE) at 1.2 to 2.5 Gy/fraction. Forty-three patients had 1.2 Gy/fraction twice a day to 69.6 Gy/58 fractions. Two hundred and five patients (82%) received platin- and taxane-based concurrent chemotherapy. Other treatment approaches included induction chemotherapy followed by radiation (n=15), induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemotherapy and radiation (n=85), concurrent chemotherapy and radiation without induction treatment (n=120), and radiation alone (n=30).

Table 1. Patient characteristics by treatment group.

| No. of Patients (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | 3CRT (n = 93) | IMRT (n=97) | PBT (n=60) | All patients (n=250) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 48 (52) | 59 (61) | 35 (58) | 142 (57) |

| Female | 45 (48) | 38 (39) | 25 (42) | 108 (43) |

| Age, years | ||||

| Median | 74 | 69 | 71 | 71 |

| Range | 47-92 | 40-87 | 45-86 | 40-92 |

| Race | ||||

| White | 83 (89) | 87 (90) | 56 (93) | 226 (90) |

| Other | 10 (11) | 11 (10) | 4 (7) | 24 (10) |

| Respiratory disease history | ||||

| Yes | 27 (29) | 40 (41) | 28 (47) | 95 (38) |

| No | 66 (71) | 57 (59) | 32 (53) | 155 (62) |

| Cardiovascular disease history | ||||

| Yes | 46 (49) | 57 (59) | 42 (70) | 145 (58) |

| No | 47 (51) | 40 (41) | 18 (30) | 105 (42) |

| Disease stage | ||||

| I, II | 17 (18) | 9 (9) | 24 (40) | 50 (20) |

| III, IV | 76 (82) | 88 (91) | 36 (60) | 200 (80) |

| Tumor histology | ||||

| Squamous cell | 33 (35) | 41 (42) | 27 (45) | 101 (40) |

| Adenocarcinoma | 33 (35) | 34 (35) | 20 (33) | 87 (35) |

| NSCLC, NOS | 27 (29) | 27 (23) | 13 (22) | 62 (25) |

| Karnofsky performance score | ||||

| >80 | 11 (12) | 18 (19) | 12 (20) | 41 (16) |

| 70-80 | 82 (88) | 79 (81) | 48 (80) | 209 (84) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current | 25 (27) | 20 (21) | 10 (17) | 55 (22) |

| Former | 63 (68) | 72 (74) | 47 (78) | 182 (73) |

| Never | 5 (5) | 5 (5) | 3 (5) | 13 (5) |

| Concurrent CRT | ||||

| No | 14 (15) | 9 (9) | 22 (37) | 45 (18) |

| Yes | 79 (85) | 88 (91) | 38 (63) | 205 (82) |

| Radiation total dose | ||||

| Median | 66 Gy | 66 Gy | 74 GyE | 69.6 Gy/GyE |

| Range | 60-84 Gy | 60-74 Gy | 60-87.5 GyE | 60-87.5 Gy/GyE |

| Radiotherapy fractionation | ||||

| Once a day | 57 (61) | 94 (97) | 60 (100) | 211 (84) |

| Twice a day | 36 (39) | 3 (3) | 0 | 39 (16) |

| Mean lung dose (n = 235) | ||||

| Median | 20 Gy | 18 Gy | 14 GyE | 17 Gy/GyE |

| Range | 4-29 Gy | 3-27 Gy | 6-22 GyE | 3-29 Gy/GyE |

| Lung V5, % (n = 235) | ||||

| Median | 53 | 53 | 33 | 49 |

| Range | 11-87 | 17-92 | 14-62 | 11-92 |

| Lung V20, % (n = 235) | ||||

| Median | 33 | 31 | 22 | 30 |

| Range | 6-45 | 4-43 | 10-40 | 4-45 |

| Mean heart dose (n = 235) | ||||

| Median | 18 Gy | 10 Gy | 3 GyE | 11 Gy/GyE |

| Range | 0.1-55 Gy | 0.1-40 | 0-26 | 0-55 Gy/GyE |

| Heart V40, % (n =235) | ||||

| Median | 23 | 8 | 3 | 9 |

| Range | 0-88 | 0-55 | 0-28 | 0-88 |

| Gross tumor volume, cm3 (n=235) | ||||

| Median | 111 | 108 | 70 | 98 |

| Range | 2.3-859 | 5.9-773 | 1.9-846 | 1.9-859 |

| Baseline DLCO, % of predicted | ||||

| Median | 65 | 67 | 63.5 | 66 |

| Range | 22-128 | 20-148 | 27-125 | 20-148 |

| Baseline FEV1, % of predicted | ||||

| Median | 63 | 74 | 69 | 68 |

| Range | 19-106 | 26-127 | 30-116 | 19-127 |

Abbreviations: 3DCRT, 3 dimension conformal radiotherapy; IMRT, intensity modulated radiation therapy; PBT, proton beam radiotherapy; NSCLC, NOS, non–small-cell lung cancer, not otherwise specified; CRT, chemoradiotherapy; lung V5, volume of normal lung receiving 5 Gy or more radiation; lung V20, volume of normal lung receiving 20 Gy or more radiation; heart V40, volume of normal heart receiving 40 Gy or more radiation; DLCO, lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second.

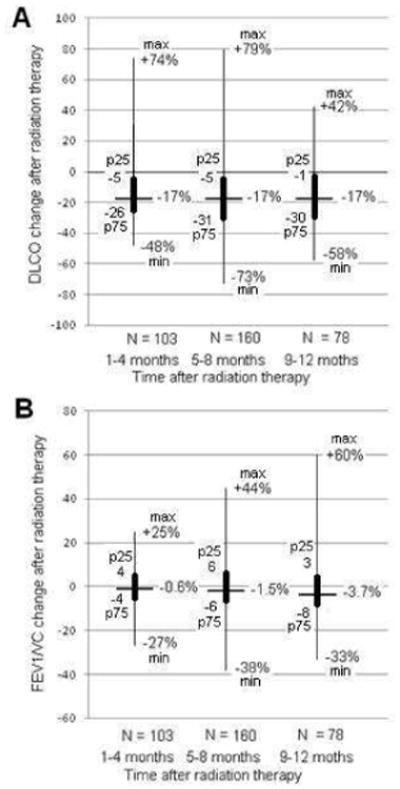

Diffusing capacity

DLCO decreased after treatment in 84 patients in T1 (82%), 126 in T2 (79%), and 59 (76%) in T3; increased in 15 patients in T1, 33 in T2, and 16 in T3; and remained unchanged in 4 patients in T1, 1 in T2, and 3 in T3. The same median DLCO change (17% of reduction) was observed for the 3 time periods after radiation therapy evaluated (Figure 2A). When evaluating those patients who had PFTs at T1 and T2 (N = 37), for those patients who had a DLCO decrease at T1 (N = 30; 82%), we observed that 14 (47%) worsened again at T2 and 16 (53%) improved. In contrast, for those who had a DLCO increase at T1 (N = 7; 18%), we found that 5 (71%) worsened at T2 and two (29%) improved again. Additionally, we evaluated those patients having PFTs at T2 and T3 (N = 46). We observed that for patients who had a DLCO decrease at T2 (N = 38; 83%), half of them worsened again at T3, two were stable, and 17 (45%) improved. The two patients that were stable at T2, worsened at T3. Finally, we observed that four out of the six patients that improved at T2, worsened at T3. The remaining two patients improved again.

Fig. 2.

Decrease (percent change from baseline) in lung diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO) and forced expiratory volume in 1 second per unit of vital capacity (FEV1/VC) after radiotherapy. Positive values indicate increase. Extreme values located over the thin line represent the maximum and minimum whereas those located over the thick line represent the interquartile range.

On univariate analysis (Table 2), a history of respiratory disease, advanced disease stage (III, IV), concurrent chemotherapy, pretreatment DLCO ≤50%, and pretreatment FEV1 ≤60% were significantly associated with larger posttreatment declines in DLCO during T1.

Table 2. Factors significantly associated with DLCO decrease (percent change from baseline) in univariate analyses.

| Variable | Present* | Significance (P) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Yes | No | ||

| Intensity-modulated radiation therapy | T2 | 14 | 21† | 0.040 |

| Proton beam radiotherapy | T2 | 9 | 21† | 0.008 |

| History of respiratory disease | T1 | 19 | 8 | 0.007 |

| T3 | 18 | 8 | 0.028 | |

| Advanced disease stage (III, IV) | T1 | 17 | 5 | 0.020 |

| T2 | 18 | 8 | 0.027 | |

| T3 | 17 | 3 | 0.017 | |

| Concurrent chemotherapy | T1 | 17 | 3 | 0.006 |

| Twice-daily radiotherapy fractionation | T2 | 28 | 15 | 0.010 |

| Radiation total dose >median | T2 | 20 | 10 | 0.006 |

| T3 | 19 | 8 | 0.021 | |

| Mean lung dose >median | T2 | 23 | 8 | < 0.0001 |

| Lung V5 >median | T2 | 18 | 11 | 0.047 |

| T3 | 19 | 9 | 0.038 | |

| Lung V20 >median | T2 | 22 | 9 | 0.001 |

| Mean heart dose>median | T2 | 21 | 10 | 0.004 |

| Heart V40 >median | T2 | 22 | 8 | < 0.0001 |

| T3 | 19 | 7 | 0.014 | |

| Gross tumor volume ≥100 cm3 | T2 | 23 | 8 | < 0.0001 |

| T3 | 20 | 9 | 0.022 | |

| Baseline DLCO ≥50% of predicted | T1 | 1 | 18 | < 0.0001 |

| T2 | 5 | 20 | 0.001 | |

| T3 | 3 | 17 | 0.009 | |

| Baseline FEV1 ≥60% of predicted | T1 | 9 | 19 | 0.014 |

Absolute posttreatment DLCO decline expressed as a percentage value (average), when each factor is either present or absent. Negative values indicate increase.

Value corresponding to patients treated with 3-dimensional conformal radiotherapy.

Abbreviations: Same as Table 1

Secondly, radiation total dose >median (69.6 Gy/GyE), GTV ≥100 cm3, advanced disease stage, pretreatment DLCO ≤50%, twice-daily radiotherapy fractionation and 3DCRT were associated with larger posttreatment declines in DLCO during T2. Additionally, lung (MLD, V5, and V20) and cardiac dosimetric parameters (MHD and V40) also associated with the DLCO change.

Thirdly, GTV ≥100 cm3, advanced disease stage, history of respiratory disease, and pretreatment DLCO ≤50% were associated with larger posttreatment declines in DLCO during T3. Moreover, the total radiation dose, lung V5, and heart V40 associated with the DLCO change after RT. MLD and lung V20 had marginal significance (P =0.056 and P =0.052, respectively).

After adjusting for the variables listed in Table 1, only pretreatment DLCO ≤50% was associated with larger posttreatment declines in DLCO during T1 (P <0.001). At T2, the following features retained statistical significance: pretreatment DLCO (P =0.002), GTV (P =0.035), and lung and heart dosimetric data except lung V5 (MLD, P <0.001; lung V20, P =0.002; MHD, P =0.009; heart V40, P =0.001). Finally, the radiation total dose (P =0.012), and the pretreatment DLCO (P =0.005), retained statistical significance at T3. When excluding on the multivariate analysis those variables which were not available for all patients (GTV and dosimetric data), we found that pretreatment DLCO, 3DCRT (vs IMRT) and concurrent chemoradiation retained significance in T1 (P <0.001, P =0.008, and P =0.037, respectively); pretreatment DLCO and 3DCRT (vs IMRT and vs PBT) in T2 (P =0.001, P =0.042, and P =0.009, respectively); and pretreatment DLCO and radiation dose in T3 (P= 0.007 and P= 0.021, respectively).

We also evaluated the effect of pretreatment PFT values as well as patient, tumor and treatment factors on major changes in pulmonary function after RT, with the cutpoint set as the upper tertile of DLCO decrement. Patients with heart V40 >median had a greater risk of DLCO impairment than did those with ≤median at T1 (OR: 2.65, P =0.040). At T2, a greater DLCO decrease was observed in those patients with GTV ≥100 cm3 (OR: 3.44, P =0.003), twice-daily radiotherapy fractionation (OR: 3.96, P =0.002), MLD >median (OR: 2.36, P =0.029), or heart V40 >median (OR: 2.53, P =0.022). In contrast, patients who underwent IMRT had lower DLCO impairment compared with those who received 3DCRT (OR: 0.38, P =0.026). Finally, a greater DLCO decrease was observed in those patients with GTV ≥100 cm3 (OR: 4.87, P =0.013), MHD >median (OR: 4.48, P =0.033), MLD >median (OR: 4.19, P =0.027), or lung V5 >median (OR: 3.4, P =0.047) at T3.

After adjusting for other covariates, only heart V40 >median retained significance (OR: 3.69, P =0.009) at T1. At T2, GTV ≥100 cm3 and twice-daily radiotherapy fractionation retained significance (OR: 3.54, P =0.004 and OR: 6.44, P =0.001, respectively). Finally, no factor retained significance at T3.

Obstruction

FEV1/VC decreased after treatment in 54 patients in T1 (52%), 89 in T2 (56%), and 52 (67%) in T3; increased in 48 patients in T1, 70 in T2, and 26 in T3; and remained unchanged in one patient in T1 and T2. We observed a decrease in the median FEV1/VC level after RT of 0.6%, 1.4%, and 3.7% in T1, T2, and T3, respectively (Figure 2B). When evaluating those patients who had PFTs at T1 and T2, for those patients who had an FEV1/VC decrease at T1 (N = 20; 54%), we observed that 8 (40%) worsened again at T2 and 12 (60%) improved. In addition, for those who had an FEV1/VC increase at T1 (N = 17; 46%), we found that 11 (65%) worsened at T2 and 6 (35%) improved again. We then evaluated those patients having PFTs at T2 and T3. We observed that for patients who had an FEV1/VC decrease at T2 (N = 26; 56%), 14 (54%) worsened again at T3 and 12 (46%) improved. Finally, we observed that 15 out of the 20 patients that improved at T2 worsened at T3. The remaining 5 patients improved again.

On univariate analysis (Table 3), only pretreatment DLCO ≤50% was associated with larger posttreatment declines in FEV1/VC during T1; twice-daily radiotherapy fractionation in T2; and pretreatment FEV1 ≤60% in T3. When evaluating those patients who had pretreatment main bronchus obstruction (by CT image) due to tumor compression (n=18) compared with those who had not, we did not observe a significant FEV1/VC change difference at any time interval between the two groups. After adjusting by covariates, only pretreatment DLCO retained statistical significance during the initial time period, T1 (P =0.024). When evaluating the effect of predictors of major changes in the FEV1/VC after RT (decrement greater than the upper tertile), we did not find a significant association with any of the patient, tumor, treatment, and pre-RT PFT factors assessed.

Table 3. Factors significantly associated with FEV1/VC decrease (percent change from baseline) in univariate analyses.

| Variable | Present* | Significance (P) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Yes | No | ||

| Baseline DLCO ≥50% of predicted | T1 | -3 | 1 | 0.024 |

| Twice-daily radiotherapy fractionation twice a day | T2 | 1 | -4 | 0.017 |

| Baseline FEV1 ≥60% of predicted | T3 | -3 | 4 | 0.019 |

Absolute posttreatment FEV1/VC decline expressed as a percentage value, when each factor is either present or absent. Negative values indicate increase.

Abbreviations: Same as Table 1

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study comparing changes in pulmonary function after definitive RT for NSCLC delivered with three modern techniques: 3DCRT, IMRT, and PBT. We observed that DLCO was more often affected than obstruction, with a much larger percentage of patients experiencing a decline in DLCO after RT, regardless of technique. Several factors were associated with a decline in diffusing capacity, including GTV, pretreatment DLCO, and dosimetric data, consistent with prior studies [3, 9].

Several prior studies have examined the effect of RT on pulmonary function with time [3,10, 11]. Miller et al. [11] reported that by 1 year, the median FEV1 and forced vital capacity were similar as baseline and the median DLCO was 90% of baseline. Contrary to Henderson et al [10], we found that baseline pulmonary function predicted decreased pulmonary function after treatment. Those patients with pretreatment DLCO ≤50% were associated with larger posttreatment declines in DLCO. Divergences in early stage (100% vs 20%) and radiation technique (stereotactic body radiotherapy vs 3DCRT/IMRT/PBT) between the two studies may explain in part this apparently contradictory result.

Our finding that diffusing capacity is affected more often and to a greater extent by radiation therapy than airway obstruction, is consistent with those of others who have reported that the largest and most consistent changes in PFT values after RT occur in DLCO [3, 4]. It may be that lung overexpansion, though affecting both FEV1 and DLCO, cannot compensate for the loss of functional alveolar surface area that is reflected in the DLCO [12, 13]. In addition, we observed a parallel in terms of the pre-treatment DLCO value as prognosis factor for post-treatment pulmonary dysfunction between lung cancer patients receiving RT and those treated with surgery. It seems that in both cases, the pre-treatment DLCO plays an important role as prognosis factor for not only pulmonary dysfunction but also for postoperative lung complications [4, 14]. We further found that DLCO is reduced in the majority of patients along the 3 time periods after radiation, whereas increased vs. decreased over time in a similar number of patients. Our findings suggest that interventions such as bronchodilators may have only modest effects on improving posttreatment pulmonary function and that patients with a substantial radiation dose to the lung would benefit instead from an intensive pulmonary rehabilitation program [15, 16].

With respect to our final aim, we found several dosimetric factors to be associated with decreased pulmonary function after RT. Specifically, the mean dose to the lung and heart, as well as lung V20 and heart V40, all correlated with posttreatment pulmonary function on univariate and multivariate analysis during the interval of 5 to 8 months after RT. However, the lung V5 did not retain significance after adjustment by other covariates. Although the specific lung and heart variables that correlate most strongly with lung toxicity is still debated in the literature [17], both the lung and heart dose are important for predicting radiation-induced lung injury and its clinical sequelae [18-20]. Our current findings add to the increasing body of literature suggesting that lung injury is multifactorial and that radiation doses to the lung and heart influence long-term cardiopulmonary function. Moreover, while we certainly acknowledge the importance of both low- and high-dose radiation in contributing to posttreatment pulmonary complications, the current study found that V5 was not associated with significant DLCO impairment. We are currently assessing if posttreatment DLCO can be used as an objective measure of lung toxicity given its relationship to radiation pneumonitis.

This study had several limitations. First, the study period was long and the population was heterogeneous in terms of both patient factors and treatment factors. As noted above, differences in type of treatment and disease stage among the radiation technology groups may have confounded the comparison of treatment modalities, although the magnitude of this effect is unclear. Prospective studies with similar baseline characteristics among groups are needed to better understand whether novel radiation techniques such as PBT or IMRT decrease the magnitude of pulmonary impairment by greater lung sparing. Moreover, the number of PFTs obtained for each patient varied, such that the results were in some respect driven by the patients who had had more posttreatment PFTs. We attempted to minimize this confounding factor by comparing PFTs for each individual patient at three time intervals before pooling the results for analysis. Finally, although we measured the potential association of various parameters on posttreatment PFTs, we did not assess the effect of these changes on clinical outcomes. That investigation is part of another study examining the effect of reductions in PFTs on performance status and survival.

In conclusion, we have found that, with definitive radiation therapy using modern techniques, diffusing capacity of the lung is reduced in the majority of the patients. We were able to elucidate several patient and treatment factors which were associated with greater reductions in lung function after treatment, including GTV and pre-radiation lung function, all of which could be used to estimate the impact of radiation therapy on an individual's respiratory status, possibly in the setting of objective models that could aid in counseling patients prior to treatment.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by MD Anderson's Cancer Center Support (Core) Grant CA16672.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the Spanish Society for Radiation Oncology (SEOR) National Congress, June 2011, Madrid, Spain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cerfolio RJ, Talati A, Bryant AS. Changes in pulmonary function tests after neoadjuvant therapy predict postoperative complications. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:930–935. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.06.013. discussion 935-936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Semrau S, Klautke G, Fietkau R. Baseline cardiopulmonary function as an independent prognostic factor for survival of inoperable non-small-cell lung cancer after concurrent chemoradiotherapy: a single-center analysis of 161 cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopal R, Starkschall G, Tucker SL, et al. Effects of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on lung function in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:114–120. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00077-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeda S, Funakoshi Y, Kadota Y, et al. Fall in diffusing capacity associated with induction therapy for lung cancer: a predictor of postoperative complication? Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liao ZX, Komaki RR, Thames HD, Jr, et al. Influence of technologic advances on outcomes in patients with unresectable, locally advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving concomitant chemoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:775–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang LC, Komaki R, Allen P, et al. Comparison of outcomes for patients with medically inoperable Stage I non-small-cell lung cancer treated with two-dimensional vs. three-dimensional radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;66:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zinner RG, Komaki R, Cox JD, et al. Dose escalation of gemcitabine is possible with concurrent chest three-dimensional rather than two-dimensional radiotherapy: a phase I trial in patients with stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. European Respiratory Journal. 2005;26:948–968. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Theuws JC, Muller SH, Seppenwoolde Y, et al. Effect of radiotherapy and chemotherapy on pulmonary function after treatment for breast cancer and lymphoma: A follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:3091–3100. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson M, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, et al. Baseline pulmonary function as a predictor for survival and decline in pulmonary function over time in patients undergoing stereotactic body radiotherapy for the treatment of stage I non-small-cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller KL, Zhou SM, Barrier RC, Jr, et al. Long-term changes in pulmonary function tests after definitive radiotherapy for lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:611–615. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(03)00182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaen J, Vazquez G, Alonso E, et al. Changes in pulmonary function after incidental lung irradiation for breast cancer: A prospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65:1381–1388. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDonald S, Rubin P, Phillips TL, Marks LB. Injury to the lung from cancer therapy: clinical syndromes, measurable endpoints, and potential scoring systems. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1187–1203. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00429-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takamochi K, Oh S, Matsuoka J, Suzuki K. Risk factors for morbidity after pulmonary resection for lung cancer in younger and elderly patients. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;12:739–743. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.254821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nazarian J. Cardiopulmonary rehabilitation after treatment for lung cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2004;5:75–82. doi: 10.1007/s11864-004-0008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riesenberg H, Lubbe AS. In-patient rehabilitation of lung cancer patients--a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:877–882. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0727-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dehing-Oberije C, De Ruysscher D, van Baardwijk A, et al. The importance of patient characteristics for the prediction of radiation-induced lung toxicity. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91:421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang EX, Hope AJ, Lindsay PE, et al. Heart irradiation as a risk factor for radiation pneumonitis. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:51–60. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.521192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong FM, Ten Haken R, Eisbruch A, Lawrence TS. Non-small cell lung cancer therapy-related pulmonary toxicity: an update on radiation pneumonitis and fibrosis. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:S42–54. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehta V. Radiation pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis in non-small-cell lung cancer: pulmonary function, prediction, and prevention. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;63:5–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]