Abstract

We hypothesized that the dynamic acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities (ACA) during the follow up of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) could be associated with poor prognosis. We conducted a retrospective analysis of 365 patients with IPSS low or intermediate-1 risk MDS who had at least two consecutive cytogenetic analyses during the follow up. Acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities was detected in 107 patients (29%). The most frequent alteration involved chromosome 7 in 21% of ACA cases. Median transformation-free and overall survival for patients with and without ACA were 13 vs. 52 months (P =0.01) and 17 vs. 62 months (P =0.01), respectively. By fitting ACA as a time-dependent covariate, multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that patients with ACA had increased risk of transformation (HR=1.40; P = 0.03) or death (HR=1.45; P = 0.02). Notably, female patients with therapy-related MDS (t-MDS) had an increased risk of developing ACA (OR= 5.26; P<0.0001), although subgroup analysis showed that prognostic impact of ACA was not evident in t-MDS. In conclusion, ACA occurs in close to one third of patients with IPSS defined lower risk MDS, more common among patients with t-MDS, but has a significant prognostic impact on de novo MDS.

INTRODUCTION

The myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) are a group of heterogeneous hematopoietic stem cell disorders characterized by peripheral blood cytopenias, bone marrow dysplasia affecting one or more of the hematopoietic stem cell lines, and increased risk of transformation into acute myeloid leukemia (AML). (Tefferi and Vardiman 2009) Approximately 20% to 30% of patients with MDS are at risk for developing AML and many patients suffer from complications related to cytopenias. (Dayyani, et al 2010) Due to the heterogeneity of the disease, several prognostic models have been developed to account for its complex biology. (Greenberg, et al 1997, Kantarjian, et al 2008, Malcovati, et al 2007) The most significant prognostic factors included in these models are the number of peripheral blood cytopenias, cytogenetic patterns, and bone marrow blast cell percentage. (Kantarjian, et al 2008) Recently, large studies have demonstrated the prognostic relevance of chromosomal defects in predicting outcome in MDS. (Schanz, et al 2012) These studies have analyzed the clinical impact of chromosomal abnormalities present at initial diagnosis. Few studies have evaluated the incidence and prognostic significance of the acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities (ACA). This is defined as the acquisition of either an abnormal clone in a karyotypically normal patient or additional defects in patients with an already abnormal chromosomal pattern. (Shaffer and Tommerup 2005) The ACA in the Philadelphia clone in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia defines transformation into advanced stages of the disease and is associated with poor outcome. (Cortes, et al 2003) In contrast, the impact of ACA on prognosis and risk of transformation into AML among patients with MDS is not known. We hypothesized that ACA could represent a phenomenon associated with genomic instability leading to increased risk of transformation to AML and decided to analyze this in the setting of patients with International Prognostic Scoring System [IPSS] defined lower risk MDS (Low and Int-1 risk = LR-MDS), (Bejar, et al 2012, Garcia-Manero, et al 2008, Greenberg, et al 1997) for whom this phenomenon will have a significant impact on prognosis. The aims of the study were to assess factors associated with the development of ACA and their impact on the natural history of patients with LR-MDS.

MATERIAL AND METHOS

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed 721 consecutive patients with low and intermediate-1 risk MDS, by the IPSS (Greenberg, et al 1997), referred to MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) between 2000 and 2010. Three-hundred sixty-five (51%) patients had cytogenetic analysis performed at least twice (at baseline and at least once thereafter) and therefore were evaluable for analysis. Morphologic diagnosis was classified by WHO classification. (Vardiman, et al 2009) Further risk stratification was also conducted by, IPSS-R, and MD Anderson Lower Risk Model (MDALRM) in order to detect higher risk population within the IPSS defined LR-MDS. (Garcia-Manero, et al 2008, Greenberg, et al 1997, Greenberg, et al 2012) Therapy related MDS (t-MDS) was defined by having prior exposure to cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy. (Vardiman, et al 2009) Although IPSS was not developed to assess prognostic risk in therapy related MDS (t-MDS), both de novo MDS and t-MDS were included in this study to evaluate pathophysiological association between ACA and prior exposure to cytotoxic therapies. However, given the biological and clinical behavioral difference between de novo MDS and t-MDS, some analyses were conducted separately for de novo MDS and t-MDS cohort (detailed below).

Cytogenetic analysis

Cytogenetic analysis was conducted in the Clinical Cytogenetics Laboratory at MDACC and was confirmed by a dedicated cytogeneticist (LA). Cytogenetic analyses were conducted on unstimulated bone marrow cells after culture (24–72 hours), and G-banding analysis was performed according to standard techniques at MDACC. The ISCN 2005 criteria were used for identification of abnormal clones. (Shaffer and Tommerup 2005) When possible, at least 20 metaphases were analyzed for each case. Karyotypes were defined as complex when they included three or more chromosomal abnormalities. ACA was defined by structural change or gain in at least 2 metaphases and loss in 3 metaphases. There were 2 patients who acquired chromosomal alterations typical to MDS but were detected in less than 2 metaphases. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was conducted in these 2 patients to confirm the ACA. (Shaffer and Tommerup 2005)

Statistical methods

Differences among variables were evaluated by the Chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. The association between ACA and patient characteristics was assessed through univariate and multiple logistic regression models. Transformation-free survival (TFS) was defined as the time interval between diagnosis date and the date of transformation or death date, whichever occurred first. Leukemic transformation was defined when blast cells in the bone marrow exceeded more than 20%. Patients who were alive and without transformation were censored at the last follow-up date. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval between diagnosis date and death date, whichever occurred first. Patients who were alive were censored at the last follow-up date. The probabilities of TFS and OS were estimated using the method of Kaplan and Meier. Cox proportional hazards regression models were fit to assess the association between TFS or OS and patient characteristics. Because ACA is a time-dependent event (i.e., event occurs during the follow up period), it was fitted in the Cox model as a time-dependent covariate. (Fisher and Lin 1999, Malcovati, et al 2007) In order to assess the accurate risk of AML transformation by having ACA, patients were considered having ACA only when ACA occurred prior to AML transformation in this time-dependent analysis. For patients who had ACA at the time of transformation, the status of ACA was considered to be “no”. In a confirmatory second step, we performed a landmark analysis. For the landmark analysis, we selected 8 months from diagnosis as the landmark, which is close to the median time to ACA development in our patient population. Patients who developed ACA after 8 months were treated as “no ACA” in this analysis. In the landmark analysis for TFS, if a patient had transformation, died, or was lost to follow-up before 8 months, that patient was excluded from the analysis. In the landmark analysis for OS, if a patient died or was lost to follow-up before 8 months, that patient was excluded from the analysis. All statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Patients

Of the 721 patients with LR-MDS referred to our institution, 356 patients had only one cytogenetic analysis and were removed from the study. Rest of the 365 patients (51%) had cytogenetic test done at least twice and therefore eligible for this study. Compared to the 356 patients who only had one cytogenetic analysis, the study group patients (n=365) were younger with more high-risk disease features, including higher rates of refractory anemia with excess blasts, higher rates of intermediate-1 risk MDS, and, higher rates of chromosome 5 and 7 abnormalities. Patients in the study group also had more neutropenia and thrombocytopenia and had higher rate of previous history of malignancy (data not shown).

Clinical characteristics of the study group (N = 365) at initial diagnosis are detailed in Table 1. Further risk stratification by IPSS-R and MDALRM (Garcia-Manero, et al 2008, Greenberg, et al 2012) revealed that a significant number of patients with LR-MDS by conventional IPSS were filtered into the higher risk group by either IPSS-R or MDALRM (Table 1). Our study cohort also included significant numbers of patients with t-MDS (26%, Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (Study group, N=365)

| Characteristics | (%) Total | (%) ACA | (%) No ACA | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=365 | N=107 | N=258 | ||

| Age ≥ 60 years | 66 | 71 | 64 | NS |

| Sex (Male) | 61 | 50 | 66 | 0.004 |

| Dx (WHO) | ||||

| RA | 28 | 21 | 30 | |

| RAEB | 35 | 38 | 34 | NS |

| t-MDS | 26 | 40 | 21 | <0.001 |

| IPSS | ||||

| Low | 24 | 21 | 26 | NS |

| Int-1 | 76 | 79 | 74 | |

| IPSS-R | ||||

| Very Low | 14 | 12 | 15 | |

| Low | 37 | 34 | 38 | |

| Intermediate | 26 | 30 | 33 | NS |

| High | 16 | 22 | 13 | |

| Very High | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| MDALRM | ||||

| Category 1 | 16 | 13 | 17 | |

| Category 2 | 44 | 43 | 44 | NS |

| Category 3 | 40 | 44 | 39 | |

| Cytogenetic | ||||

| Diploid | 60 | 51 | 60 | |

| Chromosomes 5/7 abnormalities | 16 | 21 | 13 | 0.05 |

| Others | 24 | 28 | 27 | |

| Hgb<10 g/dL | 48 | 44 | 50 | NS |

| PLT <100 ×109/L | 54 | 59 | 52 | NS |

| WBC ≥10 ×109/L | 8 | 5 | 9 | NS |

| ANC <1.5 ×109/L | 42 | 45 | 41 | NS |

| BM BL (%) | ||||

| 0–4 | 72 | 73 | 71 | |

| 5–10 | 28 | 27 | 29 | NS |

| Prior malignancy | 36 | 47 | 32 | 0.007 |

| Prior chemotherapy | 23 | 39 | 16 | <0.001 |

| Prior radiation | 14 | 19 | 12 | NS |

| SCT | 9 | 8 | 9 | NS |

* Cytogenetic risk stratification is based on the IPSS-R category.1

ACA=acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities; Dx=diagnosis; WHO=World Health Organization; RA=refractory anemia; RAEB=refractory anemia with excess blasts; t-MDS = therapy related MDS; IPSS=International Prognostic Scoring System; NS=not significant; Int-1=intermediate-1; Hgb=hemoglobin; PLT=platelets; WBC=white blood cell; ANC=absolute neutrophil count; BM BL=bone marrow blasts; SCT=stem cell transplantation.

After a median follow-up of 34 months (range, 3–127), 107 patients (29%) developed ACA. Patients who experienced ACA had slightly more bone marrow exams compared to non-ACA group (median [range], 6 [2–23] vs. 5 [2–29], P = 0.02). Distribution of IPSS-R classification and MDALRM category was not different between 2 groups. (P = 0.24 for IPSS-R, and P = 0.56 for MDALRM, Table 1). Initial cytogenetics result and hematologic parameters including bone marrow blast count were not significantly different among patients with ACA and non-ACA (Table 1). The ACA group had a significantly higher rate of prior history of malignancy (P = 0.007) or prior chemotherapy exposure (P < 0.001) than patients without ACA and thus had more patients with t-MDS (P < 0.001, Table 1). In the entire cohort, 32 patients underwent stem cell transplant (SCT). The number of patients who underwent SCT was not significantly different between ACA group and non-ACA group (Table 1).

Patterns of cytogenetic abnormalities

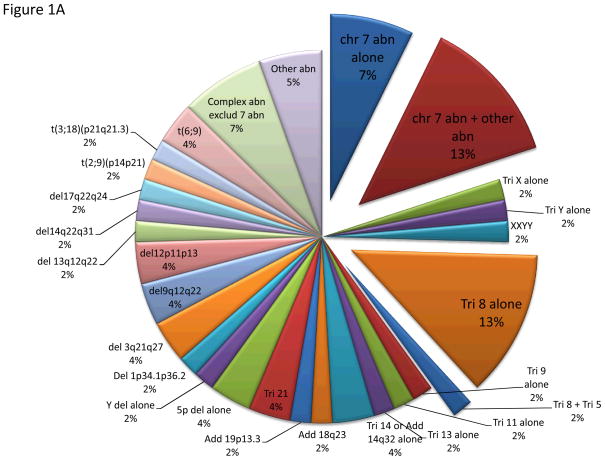

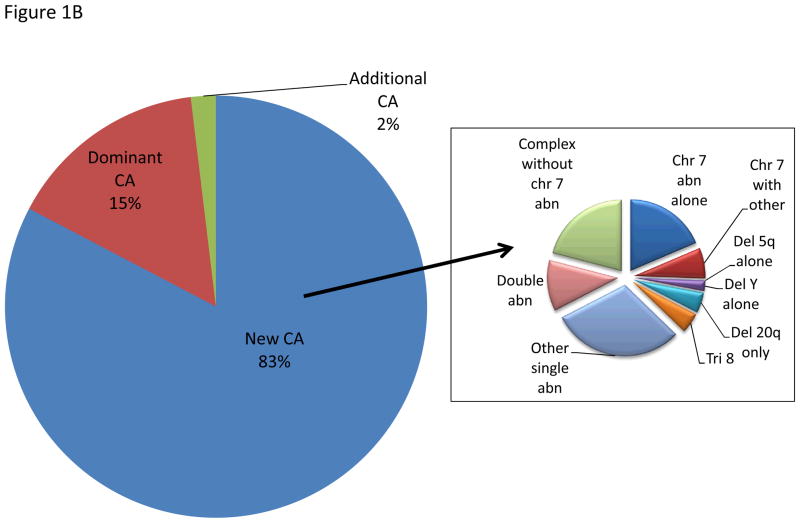

ACA was detected within a median of 8 (range, 1–77) and 7 (range, 1–64) months from diagnosis and date of referral to our institution, respectively. ACA was observed in a median number of 4 metaphases (range, 2–30 metaphases) and occurred in 55 (51%) and 52 (49%) patients with diploid and abnormal karyotype at diagnosis, respectively. The most common ACA in patients with diploid karyotype included chromosome 7 abnormality in 20% of them (as sole abnormality in 7%), followed by trisomy 8 in 15% (as a sole abnormality in 13%), and complex karyotype, excluding chromosome 7 abnormality in 6% (Figure 1A). Among the 52 patients with abnormal karyotype at diagnosis (Figure 1B), 43 (83%) acquired completely new CA, different from the original abnormalities, with single abnormality being the most common one (30%) followed by chromosome 7 abnormality in 25% (as a sole abnormality in 18%), and complex karyotype, excluding chromosome 7 abnormality in 21% (Figure 1B). Seventeen percent of patients with abnormal karyotype acquired additional abnormality, with the original clone remaining predominant in 15%.

Figure 1.

Figure 1A. Pattern of ACA in patients with diploid karyotype. This chart represents CA acquired in patients with baseline diploid karyotype.

Figure 1B. Pattern of ACA in patients with abnormal karyotype. The left chart represents CA acquired in patients with abnormal baseline karyotype. The right chart represents the new abnormalities acquired replacing the baseline clone.

Patient characteristics at the time of acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities

At the time of ACA, the median percentage of bone marrow blasts was 4% (range, 0–89%), the median WBC, hemoglobin and platelets were 3.1 × 109/L, 9.5 g/dL, and 65 × 109/L, respectively. In the fitted univariate logistic regression model (Supplemental Table 1), ACA was more frequently observed in female patients, and complex cytogenetics, with history of prior malignancy and prior chemotherapy. Based on the fitted multiple logistic regression model (Supplemental Table 2), the effect of prior chemotherapy on the ACA differs between male and female patients. Among female patients, those who received prior chemotherapy had an increased risk of developing ACA (OR= 5.26; p-value <0.0001); while in male patients, the effect of prior chemotherapy on ACA was not statistically significant (OR=1.59; p-value =0.25). For females, patients with prior chemotherapy had a higher rate of ACA (57% vs. 43%; p<0.0001); while in males this phenomenon was not observed (14% vs. 24%; p=0.25) (Supplemental Table 3).

Prognostic relevance of cytogenetic abnormalities and impact on outcome: transformation-free and overall survival

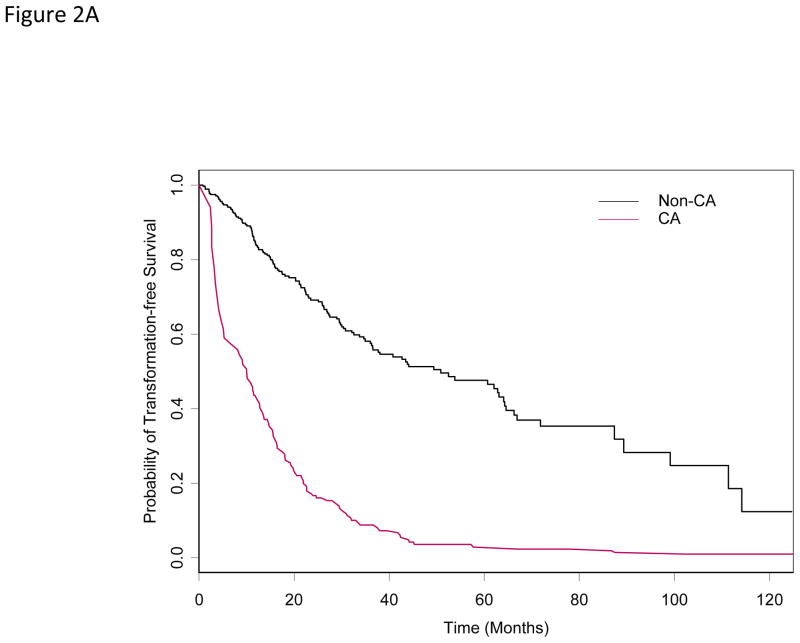

With a median follow-up of 34 months from the date of diagnosis, 216 (59%) among the 365 patients had transformation or died (N =46; 13%). Median TFS in the entire cohort was 31 months (95% CI: 27– 37). Median TFS for patients with and without ACA was13 and 52 months (P =0.01), respectively. Of the 107 patients who had ACA, 24 (22%) transformed into AML, while 22 (9%) of the 258 patients without ACA had leukemic transformation (P =0.009). Of the 24 patients who had both experienced ACA and leukemic transformation, 16 patients had ACA prior to transformation, while the rest of the 8 patients had ACA and transformation at the same time. In patients who had ACA prior to transformation, the median time from ACA to transformation into AML was 7 months (range, 1–14). In the univariate cox proportional hazards model for TFS, older patients, abnormal karyotype, higher percentage of bone marrow blasts, anemia and thrombocytopenia at diagnosis, and having received prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy had a higher risk of transformation or death (Table 2). Based on the multivariable Cox model for TFS, older patients with higher percentage of bone marrow blasts, anemia and thrombocytopenia at diagnosis and having received prior chemotherapy had a higher risk of transformation or death. After adjusting for effects of these covariates, patients with ACA had an increased risk of transformation or death with hazard ratio of 1.40 (P = 0.03) (Table 4 and Figure 2A).

Table 2.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards model for TFS

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | HR | P-value | TOTAL | EVENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Novo =No (vs. Yes) | 0.46 | 0.15 | 1.59 | 0.002 | 365 | 216 |

| Diploid = No (vs. Yes) | 0.20 | 0.14 | 1.22 | 0.15 | 365 | 216 |

| Sex = Male (vs. Female) | 0.13 | 0.14 | 1.14 | 0.35 | 365 | 216 |

| Prior Malignancy = Yes (vs. No) | 0.46 | 0.14 | 1.58 | 0.001 | 365 | 216 |

| Prior Chemo = Yes (vs. No) | 0.51 | 0.16 | 1.67 | 0.001 | 365 | 216 |

| Prior Radiation = Yes (vs. No) | 0.48 | 0.19 | 1.61 | 0.01 | 365 | 216 |

| BM Blast at Dx 5–10% (vs. 0–4) | 0.11 | 0.02 | 1.12 | <0.001 | 365 | 216 |

| WBC ≥10 ×109/L (vs. <10 ×109) | −0.05 | 0.11 | 0.95 | 0.62 | 365 | 216 |

| PLT ≥100 ×109/L (vs. <100 ×109) | −0.20 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.001 | 365 | 216 |

| HGB ≥10 g/dL (vs. < 10) | −0.10 | 0.04 | 0.90 | 0.01 | 365 | 216 |

| ANC <1.5 ×109/L (vs. ≥1.5 ×109) | −0.08 | 0.06 | 0.93 | 0.24 | 365 | 216 |

| Age ≥60 (vs. < 60) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.02 | <0.001 | 365 | 216 |

| SCT Yes (vs. No) | −0.61 | 0.30 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 365 | 216 |

Hgb=hemoglobin; PLT=platelets; WBC=white blood cell; ANC=absolute neutrophil count; chemo=chemotherapy; Dx=diagnosis; SCT=stem cell transplant

Table 4.

Multivariable Cox model for TFS and OS where CA was fitted as a time-dependent covariate

| TFS | OS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | P-value | HR | Coefficient | SE | P-value | HR |

| Age ≥ 60 (vs. < 60) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.002 | 1.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.0009 | 1.02 |

| BM Blast at Dx 5–10% (vs. 0–4) | 0.14 | 0.02 | <.0001 | 1.15 | 0.14 | 0.03 | <0.0001 | 1.16 |

| PLT ≥100 × 109/L (vs. <100 × 109) | −0.23 | 0.06 | 0.0001 | 0.79 | −0.27 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | 0.77 |

| HGB ≥10 g/dL (vs. < 10) | −0.12 | 0.04 | 0.004 | 0.89 | −0.15 | 0.04 | 0.0004 | 0.86 |

| Prior Chemo = Yes (vs. No) | 0.67 | 0.17 | <.0001 | 1.96 | 0.68 | 0.18 | 0.0001 | 1.97 |

| Diploid = No (vs. Yes) | NA | NA | NA | NA | 0.40 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 1.49 |

| SCT = Yes (vs. No) | −0.56 | 0.31 | 0.07 | 0.57 | −0.35 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.71 |

| CA=Yes (vs. No) | 0.34 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 1.40 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 1.45 |

Hgb=hemoglobin; PLT=platelets; WBC=white blood cell; ANC=absolute neutrophil count; chemo=chemotherapy; Dx=diagnosis; CA=cytogenetic abnormalities; NA=not applicable; TFS=transformation-free survival; OS=overall survival

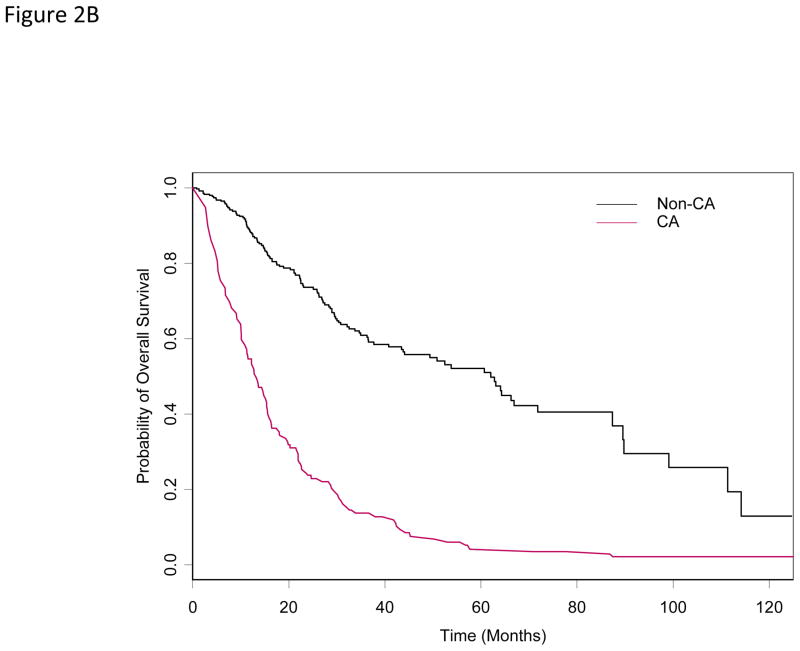

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. Transformation-free survival by ACA status (time-dependent covariate)

Figure 2B. Overall survival by ACA status (time-dependent covariate)

At last follow-up, 201 (55%) patients died. The median OS was 34 months (95% CI: 30 – 44). The median OS for patients with and without ACA were 17 and 62 months (P =0.01), respectively. In the univariate Cox proportional hazards model for OS, older patients with secondary MDS, abnormal karyotype, higher percentage of bone marrow blasts, anemia and thrombocytopenia at diagnosis, and having received prior chemotherapy or radiation therapy had a higher risk of death (Table 3) Based on the multivariable Cox model, older patients with complex cytogenetics, higher percentage of bone marrow blasts, anemia and thrombocytopenia at diagnosis, and having received prior chemotherapy had a higher risk of death. Also, after adjusting for effects of these covariates, patients with ACA had an increased risk of death (HR=1.45; P = 0.02) (Table 4 and Figure 2B).

Table 3.

Univariate Cox proportional hazards model for OS

| Variable | Coefficient | SE | HR | P-value | TOTAL | EVENT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denovo =No (vs. Yes) | 0.52 | 0.15 | 1.67 | 0.001 | 365 | 201 |

| Diploid = No (vs. Yes) | 0.33 | 0.14 | 1.39 | 0.02 | 365 | 201 |

| Sex = Male (vs. Female) | 0.07 | 0.15 | 1.07 | 0.62 | 365 | 201 |

| Prior Malignancy = Yes (vs. No) | 0.49 | 0.14 | 1.63 | 0.001 | 365 | 201 |

| Prior Chemo = Yes (vs. No) | 0.54 | 0.16 | 1.72 | 0.001 | 365 | 201 |

| Prior Radiation = Yes (vs. No) | 0.56 | 0.19 | 1.75 | 0.003 | 365 | 201 |

| BM Blast at Dx 5–10% (vs. 0–4) | 0.10 | 0.02 | 1.10 | <0.001 | 365 | 201 |

| WBC ≥10 ×109/L (vs. <10 ×109) | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.97 | 0.78 | 365 | 201 |

| PLT ≥100 ×109/L (vs. <100 ×109) | −0.23 | 0.06 | 0.80 | <0.001 | 365 | 201 |

| HGB ≥10 g/dL (vs. < 10) | −0.13 | 0.04 | 0.88 | 0.003 | 365 | 201 |

| ANC <1.5 ×109/L (vs. ≥1.5 ×109) | −0.06 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 0.34 | 365 | 201 |

| Age ≥60 (vs. < 60) | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.02 | <0.001 | 365 | 201 |

| SCT Yes (vs. No) | −0.49 | 0.30 | 0.62 | 0.10 | 365 | 201 |

Hgb=hemoglobin; PLT=platelets; WBC=white blood cell; ANC=absolute neutrophil count; chemo=chemotherapy; Dx=diagnosis; SCT=stem cell transplant

Impact of cytogenetic acquisition on transformation and overall survival: a landmark analysis

To further confirm the impact of ACA on prognosis in lower risk MDS, we repeated the analysis using a landmark approach. For this analysis, we selected 8 months from diagnosis as the landmark, which is close to the median time to ACA development in the patient population studied. The landmark analysis confirmed the initial results. Among the total of 365 patients, 59 patients had transformation, died, or were lost to follow-up before 8 months; thus, these 59 patients were excluded from the following landmark analysis. Among the remaining 306 patients, 170 (56%) had transformation or died. The median TFS was 30 months (95% CI: 23.5 – 37.6). Based on the multivariable Cox model, older patients with higher percentage of bone marrow blasts, anemia and thrombocytopenia at diagnosis and having received prior chemotherapy had a higher risk of transformation. After adjusting for effects of these covariates, patients who had ACA tended to have an increased risk of transformation or death (HR=2.02; P = 0.002). Among the total 365 patients, 55 patients died or were lost to follow-up before 8 months; thus, these 55 patients were excluded from the following landmark analysis. Among the remaining 310 patients, 162 (53%) died. The median OS was 34 months (95% CI: 25.7 – 49.3). Based on the multivariable Cox model for OS, older patients with complex cytogenetics, higher percentage of bone marrow blasts, anemia and thrombocytopenia at diagnosis, and having received prior chemotherapy tend to have a higher risk of death. Also, after adjusting for effects of these covariates, patients who had ACA tend to have an increased risk of death (HR=2.02; P = 0.002).

We also performed a sensitivity analysis. We fitted the same multivariable Cox models for TFS and OS using 3.7 months (25th percentile) and 17.1 months (75th percentile) as the landmark for ACA, respectively. While using 3.7 months as the landmark, the P-values for ACA were 0.10 and 0.007, respectively, in the fitted multivariable Cox models for TFS an OS. While using 17.1 months as the landmark, the HRs (p-values) for ACA were 1.69 (0.03) and 1.60(0.07), respectively, in the fitted multivariable Cox models for TFS an OS. These results are comparable to those of the initial landmark.

Prognostic impact of ACA in therapy-related MDS (t-MDS)

Because of the distinct biological and clinical characteristics between de novo MDS and t-MDS, we next evaluated prognostic impact of ACA in each subgroup of patients with de novo MDS and t-MDS.

In de novo MDS (N = 269), univariate analysis followed by multivariate Cox regression showed that initial bone marrow blasts more than 5%, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and older age were significantly associated with worse TFS and OS (Supplemental Table 4 and 5). After adjusting for effects of these covariates, having ACA was significantly associated with worse TFS (HR = 1.51, P = 0.02) and had strong trend with worse OS (HR = 1.44, P = 0.06).

In patients with t-MDS (N = 96), univariate analysis followed by multivariate Cox regression showed that initial bone marrow blasts more than 5% and neutropenia were significantly associated with worse TFS and IPSS Int-1 risk and neutropenia were associated with worse OS, respectively (Supplemental Table 6 and 7). After adjusting effects from these covariates, having ACA did not show a statistically significant association between TFS and OS (Supplemental Table 7).

DISCUSSION

Patients with IPSS defined lower risk MDS constitute a very heterogeneous group of patients. Experience from MDACC has indicated that median survival of this group of patients is very heterogeneous (Garcia-Manero, et al 2008). Patients with lower risk MDS are commonly offered a “watch and wait” strategy and are considered at low risk of transformation into AML. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic analysis of the acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities in a significant number of patients with IPSS defined lower-risk MDS. In this study, after a median follow-up of 34 months, ACA occurred in 29% of patients with low and intermediate-1 risk disease. These patients have been cytogenetically analyzed at least twice before MDS/AML evolution. Our study indicates that the ACA is associated with poor outcome, including higher risk of transformation and worse survival. Patients, particularly female, with previous malignancy treated with chemotherapy were at higher risk of developing ACA. Although, ACA was detected more frequently in t-MDS cases, our subgroup analysis indicates that prognostic impact of ACA is not evident in t-MDS and was only apparent in de novo MDS cases. Possible explanation for this observation is that t-MDS has more higher risk cytogenetics already at time of diagnosis and the impact of acquiring additional cytogenetic abnormalities is less prominent than that of de novo MDS. In support of this, t-MDS had more high risk cytogenetics (defined by IPSS-R cytogenetic risk)(Greenberg, et al 2012) at diagnosis (Supplemental Table 8).

Cytogenetic evolution in MDS has been studied by several other groups. Haferlach and colleagues have recently reported an incidence of “clonal evolution” of 17% among 988 patients with MDS of all stages. Similarly to our findings, clonal evolution was significantly associated with transformation to AML and shorter OS. (Haferlach, et al 2011) Wang and colleagues, have also reported a shorter survival for 18 patients among 85 patients with primary MDS with cytogenetic evolution of 25.8 months, compared with 45.4 months for patients without cytogenetic evolution. The same result was also found for time to progression. (Wang, et al 2010) Previous studies, which have included small numbers of patients with short follow-up periods, have suggested that cytogenetic evolution occurs during the course of the disease in about 14–46% of MDS patients, more commonly in those with sudden transformation to AML. (Bernasconi, et al 2010, Ghaddar, et al 1994, Suciu, et al 1990, Tricot, et al 1985, White, et al 1994) Our results have significant implications for the understanding of MDS and clinical management of patients with this disease. First, we observed that the rate of ACA was similar between patients with diploid versus other cytogenetic patterns at baseline. This is of importance as it suggests that a secondary event controls this process or that alternatively, patients with baseline abnormal karyotypes are at a different earlier temporal stage of the disease. As expected, the most common cytogenetic abnormality acquired was deletion 7, reinforcing the importance of this genomic region in the biology of MDS. Second, it is of interest that females with therapy related disease are at higher risk for developing ACA than males. This was not due to a higher incidence of patients with ovarian or breast cancer. In the future it will be important, if confirmed, to understand sex differences in the context of genetic instability. From a clinical perspective, if this data is validated it will allow the identification of a group of patients at very high risk of progression that may require closer cytogenetic follow up. The third observation that we believe is critical is the fact that we observed a median latency period of 7 months between ACA and transformation to AML. This has several implications. Analysis of molecular alterations detected at the time of ACA are likely to represent major molecular determinants of progression to AML. Also, patients in whom ACA is detected should be considered at very high risk for complications from MDS and treated as such. Conceptual model of ACA in management of MDS is shown in Figure 3. There are several limitations to our study. Due to the retrospective nature of the study design, schedule and frequency of bone marrow exams are not controlled throughout the cohort. We carefully investigated the confounding effect on outcome from the number of bone marrow exams. The number of bone marrow exams in the ACA arm was slightly higher than that of the non-ACA arm (median 6 vs. 5, P = 0.02); however, the difference was very small and we do not believe that median number difference of bone marrow exams could truly alter the incidence of detecting ACA. In fact, in patients with ACA, median BME to detect ACA was 3 (range, 2–14), which is smaller than BME performed for patients without ACA. Furthermore, patients who had more bone marrow exams (≥ 6 marrow exams, N = 185) had better OS than patients with less bone marrow exams (≤ 5 marrow exams, N = 180) (45 vs. 31 months, P = 0.02). Therefore, we concluded that a confounding effect from random bone marrow exams is minimal. Second, our model did not take into account the increasingly identified molecular alterations and somatic point mutations. (Bejar, et al 2011, Bejar, et al 2012) It is of great interest to investigate association between ACA and certain somatic mutations in the context of genetic instability in MDS and subsequent disease progression. Finally, other than SCT, our model did not take treatment effect into consideration. With all these limitations, the data presented here indicate that development of ACA is a poor prognostic feature and that patients at risk should be followed with sequential analysis. In conclusion, the acquisition of cytogenetic abnormalities occurs in close to a third of patients with IPSS defined lower-risk MDS, more common among patients with therapy related disease, although its prognostic impact is more evident in de novo MDS. Sequential cytogenetic analyses may allow the identification of subsets of patients with MDS at higher risk for transformation to AML and thus might guide treatment decisions in the future.

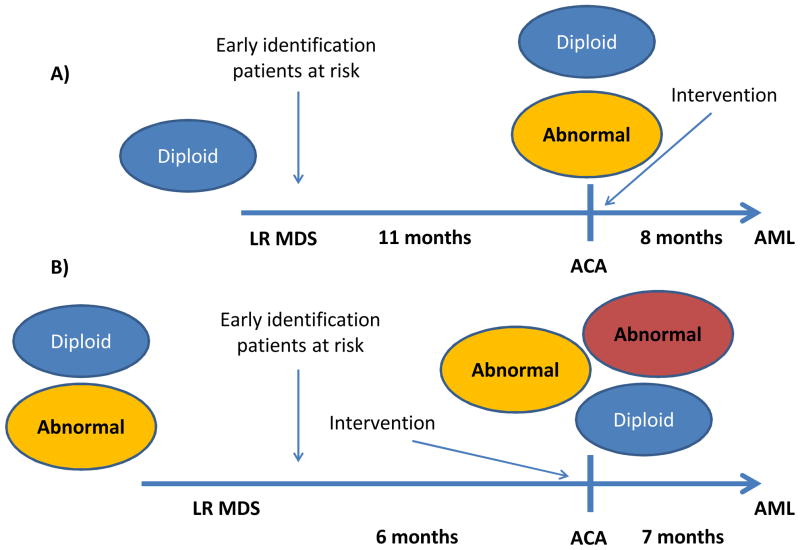

Figure 3. A model of ACA in MDS.

At baseline patients with lower risk MDS can be diploid (A) or have additional cytogenetic alterations (B). In a third of patients, additional/s cytogenetic clones (ACA or acquisition of cytogenetic alterations) are detected by conventional cytogenetic analysis. This phenomenon, in general, precedes development of acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) by a median time of 7 months. Molecular drivers of ACA are likely to be important determinants of AML transformation. The identification of patients at higher risk of ACA development may require closer follow up and more frequent cytogenetic analysis. Once patients develop ACA they should be considered for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grant RP100202 from the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, the Ruth & Ken Arnold Fund and the Edward P. Evans Foundation (GGM), Celgene Future Leaders in Hematology Award (KT), and the MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant (CCSG) CA016672

Footnotes

Contribution: EJ*and KT* collected and analyzed data and wrote manuscript; XW analyzed data and wrote manuscript; AMC, SP collected data; LA analyzed data; TK, GB, ZE, SOB,MM, WW, FS, HK provided patient material and helped write manuscript; YW and RC helped with data analysis; GGM designed study, analyzed data and wrote manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

References

- Bejar R, Stevenson K, Abdel-Wahab O, Galili N, Nilsson B, Garcia-Manero G, Kantarjian H, Raza A, Levine RL, Neuberg D, Ebert BL. Clinical effect of point mutations in myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2496–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejar R, Stevenson KE, Caughey BA, Abdel-Wahab O, Steensma DP, Galili N, Raza A, Kantarjian H, Levine RL, Neuberg D, Garcia-Manero G, Ebert BL. Validation of a prognostic model and the impact of mutations in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3376–3382. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.7379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernasconi P, Klersy C, Boni M, Cavigliano PM, Giardini I, Rocca B, Zappatore R, Dambruoso I, Calvello C, Caresana M, Lazzarino M. Does cytogenetic evolution have any prognostic relevance in myelodysplastic syndromes? A study on 153 patients from a single institution. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:545–551. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-0927-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes JE, Talpaz M, Giles F, O’Brien S, Rios MB, Shan J, Garcia-Manero G, Faderl S, Thomas DA, Wierda W, Ferrajoli A, Jeha S, Kantarjian HM. Prognostic significance of cytogenetic clonal evolution in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia on imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood. 2003;101:3794–3800. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayyani F, Conley AP, Strom SS, Stevenson W, Cortes JE, Borthakur G, Faderl S, O’Brien S, Pierce S, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G. Cause of death in patients with lower-risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer. 2010;116:2174–2179. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher LD, Lin DY. Time-dependent covariates in the Cox proportional-hazards regression model. Annu Rev Public Health. 1999;20:145–157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.20.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Manero G, Shan J, Faderl S, Cortes J, Ravandi F, Borthakur G, Wierda WG, Pierce S, Estey E, Liu J, Huang X, Kantarjian H. A prognostic score for patients with lower risk myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia. 2008;22:538–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghaddar HM, Stass SA, Pierce S, Estey EH. Cytogenetic evolution following the transformation of myelodysplastic syndrome to acute myelogenous leukemia: implications on the overlap between the two diseases. Leukemia. 1994;8:1649–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg P, Cox C, LeBeau MM, Fenaux P, Morel P, Sanz G, Sanz M, Vallespi T, Hamblin T, Oscier D, Ohyashiki K, Toyama K, Aul C, Mufti G, Bennett J. International scoring system for evaluating prognosis in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 1997;89:2079–2088. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PL, Tuechler H, Schanz J, Sanz G, Garcia-Manero G, Sole F, Bennett JM, Bowen D, Fenaux P, Dreyfus F, Kantarjian H, Kuendgen A, Levis A, Malcovati L, Cazzola M, Cermak J, Fonatsch C, Le Beau MM, Slovak ML, Krieger O, Luebbert M, Maciejewski J, Magalhaes SM, Miyazaki Y, Pfeilstocker M, Sekeres M, Sperr WR, Stauder R, Tauro S, Valent P, Vallespi T, van de Loosdrecht AA, Germing U, Haase D. Revised international prognostic scoring system for myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:2454–2465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-420489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haferlach C, Zenger M, Alpermann T, Schnittger S, Kern W, Haferlach T. Cytogenetic Clonal Evolution in MDS Is Associated with Shifts towards Unfavorable Karyotypes According to IPSS and Shorter Overall Survival: A Study on 988 MDS Patients Studied Sequentially by Chromosome Banding Analysis. Blood. 2011;118:abstract 968. [Google Scholar]

- Kantarjian H, O’Brien S, Ravandi F, Cortes J, Shan J, Bennett JM, List A, Fenaux P, Sanz G, Issa JP, Freireich EJ, Garcia-Manero G. Proposal for a new risk model in myelodysplastic syndrome that accounts for events not considered in the original International Prognostic Scoring System. Cancer. 2008;113:1351–1361. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcovati L, Germing U, Kuendgen A, Della Porta MG, Pascutto C, Invernizzi R, Giagounidis A, Hildebrandt B, Bernasconi P, Knipp S, Strupp C, Lazzarino M, Aul C, Cazzola M. Time-dependent prognostic scoring system for predicting survival and leukemic evolution in myelodysplastic syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3503–3510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanz J, Tuchler H, Sole F, Mallo M, Luno E, Cervera J, Granada I, Hildebrandt B, Slovak ML, Ohyashiki K, Steidl C, Fonatsch C, Pfeilstocker M, Nosslinger T, Valent P, Giagounidis A, Aul C, Lubbert M, Stauder R, Krieger O, Garcia-Manero G, Faderl S, Pierce S, Le Beau MM, Bennett JM, Greenberg P, Germing U, Haase D. New comprehensive cytogenetic scoring system for primary myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and oligoblastic acute myeloid leukemia after MDS derived from an international database merge. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:820–829. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer L, Tommerup N. ISCN 2005: an international system for human cytogenetic nomenclature. S. Karger; Basel: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Suciu S, Kuse R, Weh HJ, Hossfeld DK. Results of chromosome studies and their relation to morphology, course, and prognosis in 120 patients with de novo myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1990;44:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(90)90193-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Myelodysplastic syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1872–1885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0902908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricot G, Boogaerts MA, De Wolf-Peeters C, Van den Berghe H, Verwilghen RL. The myelodysplastic syndromes: different evolution patterns based on sequential morphological and cytogenetic investigations. Br J Haematol. 1985;59:659–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1985.tb07361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, Harris NL, Le Beau MM, Hellstrom-Lindberg E, Tefferi A, Bloomfield CD. The 2008 revision of the WHO classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood. 2009;114:937–951. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-209262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Wang XQ, Xu XP, Lin GW. Cytogenetic evolution correlates with poor prognosis in myelodysplastic syndrome. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2010;196:159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AD, Hoy TG, Jacobs A. Extended cytogenetic follow-up and clinical progress in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) Leuk Lymphoma. 1994;12:401–412. doi: 10.3109/10428199409073781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.