Abstract

Islet transplantation is a promising therapy for type I diabetes mellitus, with both islet yield and islet size playing important roles in transplant outcomes. Some key factors influencing islet yield have been identified, but with conflicting results. In this study, we analyzed 276 islet isolations performed at a single center to identify variables that influence islet yield, and additionally, influence islet size and size distribution. Pearson correlation analyses demonstrated that donor BMI had a positive correlation with pancreas size, actual islet count (AIC), and islet equivalent (IEq)/g (all p ≤ 0.009), while CIT had a negative correlation with AIC and IEq/g (all p ≤ 0.003). However, neither BMI nor CIT had any correlation with islet size or islet size distribution. Donor age, sex, and organ preservation solutions were shown to have no correlation with islet yields and size distribution. Finding a balance between digestion time and digestion rate is important for islet yield and size distribution this is demonstrated when an isolation is overdigested (median split: >74%) there is an increase in islet counts, however there is also an increase in smaller islets produced. Of the three collagenases analyzed, Sigma V had the lowest digestion rate, (mean=65%), approximately 5% and 10% lower than Roche Liberase HI (p = 0.04) and Serva NB1(p = 0.0003), respectively; however the Sigma V group showed better islet size preservation than the other two enzymes. Yet, overall the enzymes resulted in similar IEq/g digested tissue. Among 276 isolations, 70.2% of the isolated islets were smaller than 150 μm, the average in situ size, and contributed only 20.4% to total IEq, while 7.4% of islets were larger than 250 μm, but contributed 42.4% to total IEq. In summary, BMI and CIT are the most useful donor variables for predicting islet yield, but selection of enzyme and balancing digestion time and digestion rate are also important for isolation success.

Keywords: Pancreatic Islet of Langerhans, Islet Isolation, Human Islet Transplantation, AIC, IEq/g, Islet Size, and Size Distribution

INTRODUCTION

Islet transplantation has become a promising alternative therapy for type I diabetes mellitus since the introduction of the Edmonton protocol in 2000 (1). Two key findings were introduced with the Edmonton protocol: first, islet mass is an important factor for the success of islet transplantation in that a total of ~12,000 islet equivalents (IEq)/kg recipient body weight are required to achieve insulin independence; and second, the Edmonton protocol demonstrated success of a steroid-free immunorepression regimen for human islet transplantation. Researchers continue to improve upon the Edmonton protocol; however, there are still inconsistent short and long-term success rates between centers. Therefore, in order to attain widespread clinical application, current organ preservation and isolation techniques need to be improved to consistently achieve the necessary high islet quality and quantity. In addition, careful selection of immunosuppressive regimen with limited β-cell toxicity, and the discovery of new transplant sites with a better microenvironment for achieving long-term islet grafting and survival are important.

Pancreatic islets of Langerhans are a well-defined 3-dimentional cluster, consisting of 1500–2000 cells, with an average diameter of 150 μm (range of 50–500 μm). A healthy adult human pancreas contains approximately one million islets, with a total islet mass equal to 1–2% of the total pancreas weight. In vitro, islet yields are measured as either actual islet count (AIC) or islet equivalent (IEq), a volumetric quantification of islet mass. An islet with a diameter of 150 μm is considered the standard to convert islet mass into IEq (2). Therefore, a larger islet contributes to the IEq more than a smaller islet. The overall mass of the isolated islet population and the size distribution of the individual islets are mainly influenced by three categories of factors: donor factors (age, sex, and body mass index [BMI]); pre-isolation and isolation factors (quality of the pancreas flush and preservation, cold ischemia time, pancreas size, enzyme used for digestion, digestion time and rate, purification medium, and protocol), and post-isolation factors (culture medium type, temperature, and length).

Clinical studies have produced inconsistent results regarding whether transplanted IEq is correlated with the probability of attaining insulin independence (3, 4). The inaccuracy of manual quantification of islet mass, with its subjectivity and potential for error, may be one reason for the inconsistent results. Vigorous efforts have been made to overcome the disadvantage of the standard manual evaluation of islet mass (5–8) through the use of computer or digital-assisted approaches. However, no accurate method currently exists.

Recent evidence also suggests that small islets are superior for human islet transplantation. This has been observed clinically in that patients that received smaller islets needed fewer islets to achieve the same C-peptide production as patients who received a greater number of larger islets (3). Similar results have also been demonstrated in a rodent model by MacGregor et al. In these studies, all animals failed to achieve normoglycemia when larger islets were transplanted in a minimal mass model, whereas 80% of the animals reversed diabetes when smaller islets were transplanted in the same model (9). In addition, glucose-stimulated insulin secretions of smaller rodent and human islets in vitro are superior to larger islets (10, 11).

In spite of the emerging evidence demonstrating that islet size may play an important role in transplant outcomes in addition to islet mass, factors that potentially impact islet size and size distribution in islet preparations have not been systematically analyzed. In the current study, we retrospectively examined a large sample of human islet isolation preparations performed at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) with the aim to determine whether donor and isolation factors influence islet size. Our results may help improve pancreas preservation and islet isolation techniques with the goal of achieving a more consistent islet product for transplantation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pancreas procurement and isolation activities

The pancreata were provided by organ procurement organizations (OPO) with consent from donors. The organs were cold flushed with either University of Wisconsin (UW) or Histidine-Tryptophan-Ketoglutarate (HTK), depending upon the protocol used by the individual OPO, and stored at 4 °C before transport to UIC for islet isolation. The pancreatic islets were isolated according to previously described procedures (1, 2, 12). In brief, pancreata weights were quantified after the initial surface decontamination and excess fat trimming. One of three different types of collagenase (Roche Liberase HI, Serva NB1, and Sigma V) was then infused into the pancreata via the pancreatic duct. The inflated pancreata were then cut into 10–12 pieces and placed in a Ricordi chamber with a close-loop circulation system equipped with a heating controller, tissue sampling port, and tissue collection outlet (13). The pancreatic tissue digestion and islet dissociation were maintained at 35–37 °C and digestion efficacy was determined by microscopic observation of islet cleavage (degree of islets released from exocrine tissue) and tissue volume. The dilution phase started when the digestion was stopped and maintained for an additional 30–60 minutes.

After the dilution phase, the digested tissue was washed to remove traces of enzyme and incubated in UW solution on ice for 30 minutes. A refined UIC-UW/Biocoll (UIC-UB) continuous density gradient (14), consisting of a mixture of a high density solution (1.078 g/mL: 40% Biocoll (Cedarlane) and 51% UW) and a low density solution (1.068 g/mL: 30% Biocoll and 70% UW), was used for the separation of islets from exocrine tissues in a COBE 2991 Cell Separator (CARIDIAN BCT). Following the centrifugation process, the separated tissues were collected in 12 fractions. The first two fractions were discarded because the tissue volume is minimal (often less than 0.01 mL) and consists mostly of ductal and adipose cells. For the remaining 10 fractions, corresponding to the aforementioned continuous gradient from 1.068 g/mL to 1.078 g/mL, 30 mL of fluid volume were collected in each fraction and then the fractions were recombined based on the percentage of islet purity.

Assessment of islet yields in AIC and IEq

Final islet yields were measured both in AIC and IEq according to previously described methods. In brief, 30 μL of 1% Dithizone (DTZ) solution was added into 1.0 mL of islet sample (250 X dilution factor), for 1–2 minutes at room temperature to stain for Zinc. Red DTZ-stained islets were counted using a reticle certified to a correction factor of 0.98 to 1.02 in the eyepiece of a light microscope at 40 X. The distance across the two spaces on the calibrated reticle in the eyepiece equals 50 μm. The islets smaller than 50 μm were not counted since their contribution to IEq was not substantial. Total AIC were then calculated by multiplying by a dilution factor of 250. Eight discrete categories were designated for islet size quantification: 50 – 100, 100 – 150, 150 – 200, 200 – 250, 250 – 300, 300 – 350, 350 – 400, and > 400 μm. By multiplying AIC in each size category by an IEq conversion factor (0.167, 0.648, 1.685, 3.500, 6.315, 10.352, 15.833, and 32.500, respectively) and summing, the total IEq was then determined.

Data analysis criteria

Any isolation needing more than one purification process was excluded from this analysis because a prolonged exposure of islets to UW from a second or third purification may cause changes in islet size. There were 276 human islet isolations with complete data, which were therefore appropriate for the analysis.

STASTISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 (Cary, NC), and R Project for Statistical Computing, version 2.13.1. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.01 to minimize type 1 error from the multiple comparisons. Data were checked for normality and log transformed when necessary (e.g. AIC, IEQ/g pancreas).

Sample characteristics are presented as means ± standard deviations (SD), medians, or frequencies. Pearson correlations were calculated to determine associations between donor and isolation characteristics and islet yields to utilize the data as continuous variables; biserial correlations were calculated when a binary variable (sex, preservation solution) was one of the variables. The magnitude of the coefficients were categorized as no correlation (0–0.1), small correlation (0.1–0.3), medium correlation (0.3–0.6), large correlation (0.6–0.8), and measuring the same characteristic (0.8–1.0).

Associations of collagenase with donor and isolation characteristics and islet yields were determined using the overall F-tests and t-tests from regression models with collagenase as a dummy variable and Sigma as the reference group for continuous variables, and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. Frequencies and cumulative frequencies of AIC and IEq were also determined across eight islet size categories.

The data was then stratified into two groups (median splits for age, BMI, pancreas size, CIT, digestion time or digestion rate; sex or preservation solution). Multi-variable mixed linear regression models were used to determine whether the AIC distributions across islet size categories differed between the two levels of these factors (e.g. sex). These mixed models incorporated the correlation due to clustering by specifying the unique isolation identification number as the unit of cluster, and specified the autoregressive covariance structure with empirical standard errors.

Lastly, AIC frequencies within the eight islet size categories were compared between collagenase type using t-tests from mixed regression models with collagenase as a dummy variable and the Sigma as the reference group. Modification of the effect of collagenase on islet size distribution was tested by stratifying into two groups (median splits for age, BMI, pancreas size, CIT, digestion time or digestion rate; sex or preservation solution) and testing for interactions; no variables were found to modify the effect of collagenase. Whether differences by collagenase were confounded by other donor or isolation characteristics was tested by entering each variable individually into each mixed model and noting any substantial change in the regression coefficients; no variables were found to confound the effect of collagenase.

RESULTS

General characteristics

Donor and isolation characteristics and outcomes of 276 isolations are listed in Table 1; results are comparable to other published studies. Of particular note, Roche Liberase HI was the most common collagenase used in the current study as it was the most widely used enzyme until it was discontinued in 2007. Mean ± SD AIC was 297,891 ± 178,313 (median 257,816). Mean ± SD IEq per gram digested tissue was 2,943 ± 1,702 (median 2,684).

Table 1. Donor and isolation characteristics and islet yields.

Continuous characteristics are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and median. Categorical characteristics are expressed as frequencies. n = 276.

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| n | 276 |

| Age (years) | 48.8 ± 11.7 |

| Sex | Male: 56.5%, Female: 43.5% |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.1 ± 5.8 |

| Pancreas size (g) | 105.1 ± 30.7 |

| Preserv. soln | UW: 59.4%, HTK: 40.6% |

| CIT (hrs) | 9.2 ± 2.7 |

| Collagenase used | Roche Liberase HI: 58.7% Serva NB1: 24.3% Sigma V: 17.0% |

| Dig. time (min) | 16.4 ± 4.9 |

| Dig. rate (%) | 70.7 ± 15.5 |

| AIC | Mean: 297,891 ± 178,313, Median: 257,816 |

| IEQ/g pancreas | Mean: 2.943 ± 1.702, Median: 2.684 |

Islet size distribution and contribution to IEq

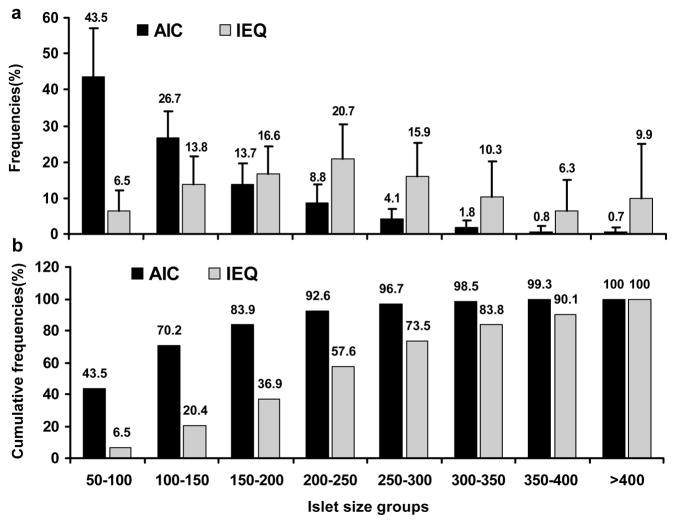

Figure 1a and 1b show the average size distribution of human islets expressed as AIC and IEq. In our isolated human islet preparations, 70.2% of the AICs were less than 150 μm (the average human islet size in situ) but contributed only 20.4% to total IEq; while 7.4% of islets were larger than 250 μm, but contributed 42.4% to total IEq.

Figure 1. Frequencies and cumulative frequencies of AIC and IEq across eight islet size categories.

(a) Frequencies of AIC and IEq across eight islet size categories. (b) Cumulative frequencies of AIC and IEq across eight islet size categories. n = 276.

Correlation analysis of key donor and isolation factors and islet yields

Pearson correlations are shown in Table 2. Donor age was negatively correlated with the digestion rate (r = −0.16, p = 0.006), indicating that older donor age was associated with a lower pancreas digestion rate. Male donors had a significantly larger pancreas size than females (p < 0.0001). Donor BMI positively correlated with pancreas size, AIC, and IEq/g (all p ≤ 0.009). Donor pancreas size had a positive correlation with AIC (r = 0.20, p = 0.001) but had a negative correlation with IEq/g (r = −0.25, p < 0.0001), indicating that a larger pancreas size yields greater AIC with a smaller IEq/g. No characteristics were associated with preservation solution.

Table 2. Pearson correlations between donor and isolation characteristics and islet yields.

n = 276. p value < 0.01 is considered statistically significant.

| Pearson Correlation Coeffient (p-value) | BMI | Pancreas size | Dig. Time | Dig. Rate | AIC (log) | IEQ/g (log) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | −0.12 (0.05) | 0.04 (0.51) | 0.06 (0.32) | −0.16 (0.006) | −0.01 (0.82) | −0.03 (0.58) |

| Sex (0=F, 1=M) | −0.07 (0.22) | 0.28 (<0.0001) | −0.03 (0.58) | 0.07 (0.26) | −0.01 (0.86) | −0.14 (0.02) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.32 (<0.0001) | −0.04 (0.55) | 0.05 (0.38) | 0.29 (<0.0001) | 0.16 (0.009) | |

| Pancreas size (g) | 0.10 (0.10) | −0.05 (0.44) | 0.20 (0.001) | −0.25 (<0.0001) | ||

| Preserv. soln (0=UW, 1=HTK) | 0.08 (0.17) | 0.07 (0.22) | 0.03 (0.60) | −0.05 (0.43) | ||

| CIT (hrs) | −0.20 (0.0007) | −0.07 (0.28) | −0.19 (0.001) | −0.18 (0.003) | ||

| Dig. time (min) | −0.04 (0.51) | −0.21 (0.0004) | −0.25 (<0.0001) | |||

| Dig. rate (%) | 0.16 (0.009) | 0.17 (0.004) | ||||

| AIC (log) | 0.90 (<0.0001) |

CIT was negatively correlated with digestion time, AIC, and IEq/g (all p ≤ 0.003). These results suggest that longer ischemia time is associated with shorter digestion time and smaller islet yields. Digestion time had a negative correlation with AIC and IEq/g (p = 0.0004 and <0.0001, respectively). However, pancreatic digestion rate had a positive correlation with both AIC and IEq/g (p =0.009 and 0.004, respectively). AIC was strongly correlated with IEq/g (r = 0.90, p < 0.0001).

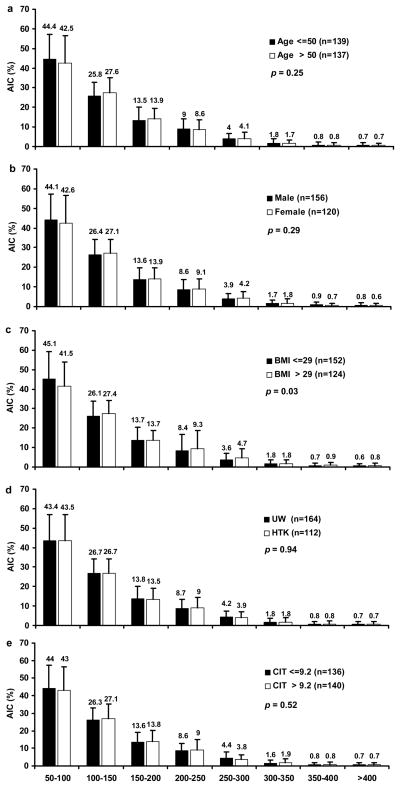

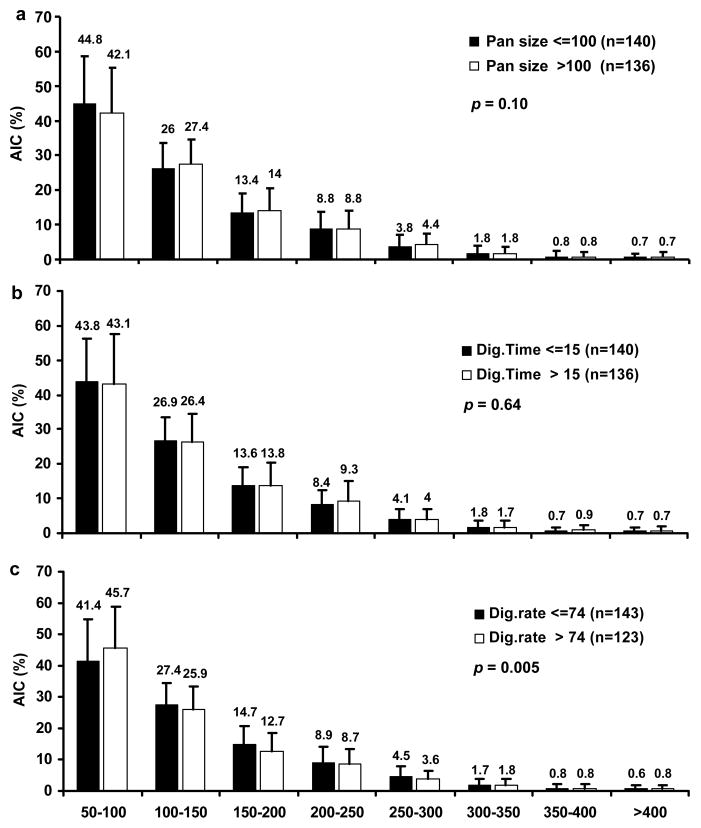

Impact of pre-isolation and isolation factors on islet size distribution

The islet size distribution across eight islet size groups were compared between two strata of key pre-isolation and isolation factors (Figures 2 and 3, respectively). None of the pre-isolation factors (age, sex, BMI, preservation solution, and CIT) altered the overall islet size distribution (p = 0.03–0.94). The isolation factors pancreas size (p = 0.10) and digestion time (p = 0.64) also did not impact the overall islet size distribution. However, a greater digestion rate (> 74%) yielded a greater proportion of islets < 100 μm and a smaller proportion of islets > 100 μm when compared with lower digestion rates (≤ 74%; p = 0.005), indicating a shift towards smaller islets when digestion rates increase.

Figure 2. AIC frequencies within eight islet size categories stratified by pre-isolation characteristics.

(a) AIC frequencies stratified by donor age > 50 and ≤ 50 years. (b) AIC frequencies stratified by sex (male vs. female). (c) AIC frequencies stratified by BMI > 29 and ≤ 29. (d) AIC frequencies stratified by preservation solution (UW vs. HTK). (e) AIC frequencies stratified CIT > 9.2 hrs and ≤ 9.2 hrs. n = 276. p value < 0.01 is considered statistically significant for comparison of AIC distributions across islet size categories between the two categories.

Figure 3. AIC frequencies within eight islet size categories stratified by isolation characteristics.

(a) AIC frequencies stratified by donor pancreas size > 100 g and ≤ 100 g. (b) AIC frequencies stratified by digestion time > 15 min and ≤ 15 min. (c) AIC frequencies stratified by digestion rate > 74% and ≤ 74%. n = 276. p value < 0.01 is considered statistically significant for comparison of AIC distributions across islet size categories between the two categories.

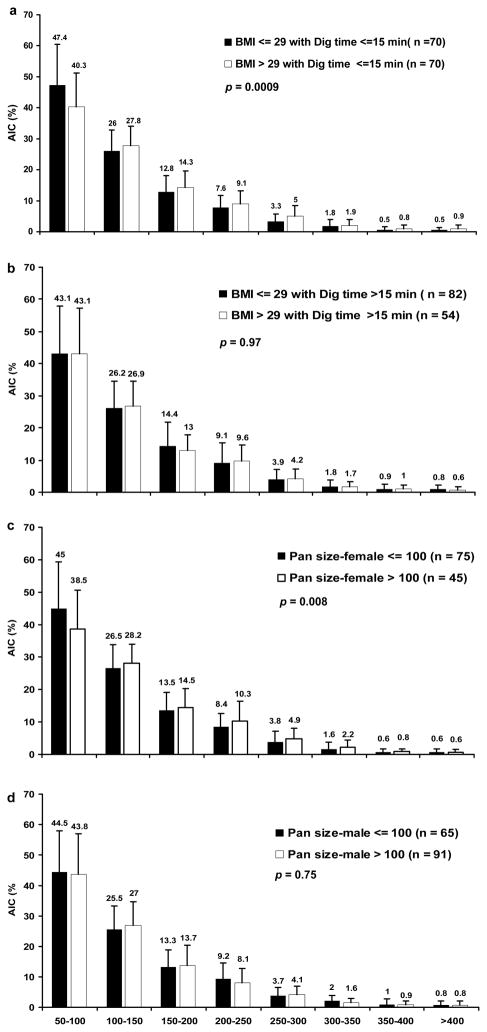

Association analysis of the impact of BMI with digestion time on islet size distribution was also conducted (Figure 4a and b), showing that when digestion time less than 15 min, donor BMI has significant impact on islet size distribution with an overall p value of 0.0009 while when digestion time more than 15 min, the BMI impact on islet size was not significant (p = 0.97). For female donors with pancreas size more than 100 g, isolated islet sizes were significant bigger than the female donors with pancreas size less than 100 g (p = 0.008). However, size distribution differences were not observed in male donors (p = 0.75) (Figure 4c and d).

Figure 4. Modification of the distribution of AIC frequencies within eight islet size categories stratified by isolation characteristics.

(a and b) AIC frequencies stratified by donor BMI > 29 and ≤ 29 for digestion time >15 min and ≤ 15 min. (c and d) AIC frequencies stratified by donor pancreas size > 100 g and ≤ 100 g for females and males. p value < 0.01 is considered statistically significant for comparison of AIC distributions across islet size categories between the two categories.

Impact of collagenase used in digestion phase on islet size distribution

Donor and isolation characteristics and islet yields were compared among the three enzymes used in Table 3. Donor age, sex, BMI, and preservation solution were not found to significantly differ between the three collagenase groups. Collagenase used was associated with the following variables: pancreas size (Roche Liberase HI: 112.3 g ± 30.1, Serva NB1: 95.1 g ± 29.3, and Sigma V: 94.6 g ± 28.2; overall F-test p<0.0001); ischemia time (Roche Liberase HI: 8.8 hrs ± 2.5, Serva NB1: 9.3 hrs ± 2.9, and Sigma V: 10.7 hrs ± 2.5;); digestion time (Roche Liberase HI: 17.6 min ± 5.2, Serva NB1: 14.4 min ± 4.5, and Sigma V: 15.2 min ± 2.6;); digestion rate (Roche Liberase HI: 70.3% ± 15.3, Serva NB1: 75.8% ± 13.0, and Sigma V: 65.0% ± 17.5;); AIC (log) (Roche Liberase HI: 12.5 ± 0.6, Serva NB1: 12.2 ± 0.7, and Sigma V: 12.3 ± 0.6;). However, there was no significant difference of IEq/g pancreas among the three groups.

Table 3. Comparison of donor and isolation characteristics and islet yields by collagenase.

n = 276. p value < 0.01 is considered statistically significant.

| Roche | Serva | Sigma | p-value Roche vs. Sigma | p-value Serva vs. Sigma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 162 | 67 | 47 | ||

| Age (years) | 48.5 ± 11.6 | 49.8 ± 12.5 | 48.6 ± 11.1 | 0.96 | 0.59 |

| Sex | Female: 43.2% Male: 56.8% |

Female: 41.8% Male: 58.2% |

Female: 46.8% Male: 53.2% |

0.66 | 0.60 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.9 ± 6.1 | 27.9 ± 5.4 | 28.1 ± 4.9 | 0.06 | 0.85 |

| Pancreas size (g) | 112.3 ± 30.1 | 95.1 ± 29.3 | 94.6 ± 28.2 | 0.0004 | 0.93 |

| Preserv. soln | UW: 56.8% HTK: 43.2% |

UW: 59.7% HTK: 40.3% |

UW: 68.1% HTK: 31.9% |

0.17 | 0.36 |

| CIT (hrs) | 8.8 ± 2.5 | 9.3 ± 2.9 | 10.7 ± 2.5 | <0.0001 | 0.005 |

| Dig. time (min) | 17.6 ± 5.2 | 14.4 ± 4.5 | 15.2 ± 2.6 | 0.002 | 0.41 |

| Dig. rate (%) | 70.3 ± 15.3 | 75.8 ± 13.0 | 65.0 ± 17.5 | 0.04 | 0.0003 |

| AIC (log) | 12.5 ± 0.6 | 12.2 ± 0.7 | 12.3 ± 0.6 | 0.006 | 0.67 |

| IEQ/g pancreas (log) | 7.9 ± 0.6 | 7.7 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 0.6 | 0.29 | 0.66 |

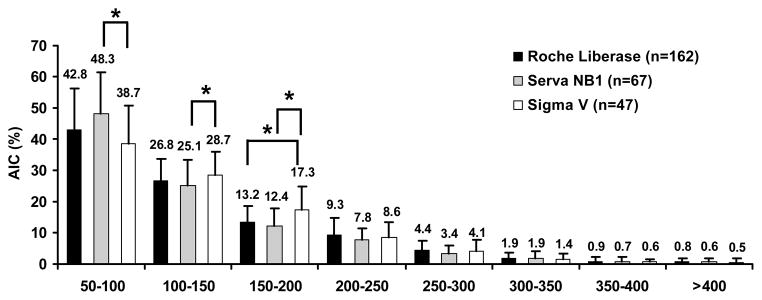

We further analyzed the impact of the three enzymes on the AIC frequencies within the eight islet size categories (Figure 4). The Sigma V had a significantly higher AIC frequency in the 100 – 150 μm and 150 – 200 μm size groups, and a significantly lower AIC frequency in the 50–100 μm size group. There were no significant differences in AIC frequencies among the three enzymes for the size groups larger than 200 μm. Adjusting the models for digestion rate, did not substantially change the differences between collagenase in the three smallest islet size groups.

DISCUSSION

One of the limiting factors to the widespread application of islet transplantation is the need for a large numbers of islets, from one or multiple pancreata, per recipient. Previous studies have demonstrated that a number of key determining factors are associated with islet yield (15–18), such as donor age, BMI, pancreas size, pancreatic quality, enzymes, and digestion duration. These are often considered during organ screening prior to islet isolation, and are used as predictors of isolation success. However, these studies only analyzed the impact on overall islet yield in terms of AIC, IEq, or AIC/IEq. To the best of our knowledge, no analysis has been conducted to determine the impact of these factors on islet size and size distribution across discrete size categories.

Theoretically, all the aforementioned pre-isolation and isolation factors could influence islet yield and size distribution in a given islet preparation. However, human islet isolations consist of multiple harsh physical and chemical processes, such as long ischemia times, enzymatic digestion and dissociation, and islet purification. Therefore, the contribution of each factor to islet yield and size could be unchanged, increased or decreased during each step of the isolation process.

Our analysis of 276 isolations demonstrated that, on average, 70.2% of AICs are smaller than a standard IEq (less than 150 μm) and contribute to only 20.4% of the total IEq (Figure 1), indicating that a significant amount of islets are fragmented or damaged during the isolation process. In a previous study, it was also shown that the average in situ insulin positive cross-sectional area, a measure of islet size prior to digestion, has no correlation with the proportion of small islets of given isolated islet products, but has a correlation with collagenase used for tissue digestion, suggesting the yields comprised of small islets are a direct result of the isolation itself (19). In addition, our analysis showed that larger islets (> 250 μm) make up only 7.4% of the AIC but contribute to 42.4% of the total IEq (Figure 1).

Donor age did not have any significant association with either AIC, IEq/g (Table 2) or islet size (Figure 2a). Male donors were found to have a larger pancreas size than female donors, however donor sex had no significant correlation with AIC, IEq/g, or islet size distribution (Table 2 and Figure 2b), suggesting that any influence of donor sex on final islet yield is not decisive and is probably out-weighed by other factors, such as BMI and CIT.

Because the quality of the pancreas preservation is a critical factor associated with islet isolation success, the solutions used for pancreas flush and storage have drawn much attention. UW has been considered the gold standard for pancreata intended for islet isolation. In this analysis, HTK solution was found to have similar effects as UW on digestion time, digestion rate, AIC, and IEq/g (Table 2) and minimal impact on islet size and size distribution (Figure 2d). These results are consistent with our previous study (20).

Donor BMI had a significant positive correlation with pancreas size, AIC, and IEq/g (Table 2), which is consistent with other studies (19, 21). It has been suggested previously that increased fat infiltration in the pancreas may facilitate islet release during the collagenase digestion (21). However, this analysis showed that donor BMI had no correlation with either digestion time or digestion rate (Table 2), indicating that the positive correlation of donor BMI with AIC and IEq/g are more likely a function of the greater number of islets in pancreata from individuals with higher BMI. This is indirectly supported by Figure 2c, which shows that the overall size distribution did not differ between groups stratified by BMI.

As previously demonstrated, prolonged cold ischemia time is detrimental to islet yield. In this study, we also found that CIT had a significant negative correlation with AIC and IEq/g, as well as digestion time (Table 2). However, the impact of CIT on islet size and size distribution was minimal (Figure 2e,). Both results suggest that the impact of ischemia-associated islet cell injury is more detrimental to islet yield than islet size distribution.

Finding the appropriate balance between the pancreas digestion time and digestion rate, which has been found to be operator dependent, is essential to the human islet isolation process. Our results demonstrated that digestion time was not associated with digestion rate (Table 2). However, digestion time had a significant negative correlation with AIC and IEq/g, while digestion rate had a positive correlation with AIC and IEq/g. Digestion times < 15 mins did not have a significant impact on overall size and size distribution (Figure 3b). In comparison, when the digestion rate was > 74%, there was a greater percentage of small islets and a smaller percentage of large islets (Figure 3c), indicating that pancreatic overdigestion can fragment islets.

Because digestion time and rate are primarily influenced by the collagenase used in the digestion phase, we further compared the three different collagenases utilized in our isolations. Sigma V had the lowest digestion rate, 5–10% less than both Roche Liberase HI and Serva NB1, while Roche Liberase HI had the longest digestion time and highest AIC. However, all three enzymes had similar IEq/g (Table 3). Sigma V preserved islet size better than Roche Liberase HI and Serva NB1, showing a significantly higher number of islets in the larger size groups (Figure 4). Together, these data indicate that Sigma V has an effect equal to that of purified enzymes on islet yield, but more efficiently releases islets from pancreatic tissue, while better preserving islet size. This is consistent with our previous study showing that the Sigma V has similar human islet isolation and clinical outcomes compared to highly purified enzymes, such as Serva NB1, with little lot-to-lot variation (22).

There are several conclusions derived from this study worth emphasizing. First, donor BMI is an important factor for determining isolation success, with a significant positive association with islet yield (AIC and IEq/g), but not islet size. Second, it is important to reduce cold ischemia time and prevent ischemia-reperfusion associated islet cell injury. It has been shown that UW and HTK have comparable efficacy for preserving pancreata intended for islet isolation, however, for organs with prolonged ischemia time, the efficacy of both solutions is diminished. While both solutions show similar effectiveness, it is necessary to find alternatives or to improve these existing preservation methods to enhance islet function. Lastly, a systematic analysis of the essential components of collagenase is necessary to ultimately deliver a well-defined enzyme blend that can provide a reliable and consistent islet product. This is particularly significant in the case of research pancreata, where the implementation of a low-cost collagenase would increase the amount of isolations performed for the purpose of research.

There are limitations to this study, mainly the imprecise assessment techniques that are commonly employed during the islet isolation procedure. Subjectivity is inherent in the established methods for islet yield and size. However, we believe that variation due to user error and subjectivity did not substantially affect this analysis because all isolations were performed by experienced isolation technicians, according to a standardized islet isolation protocol. A second limitation is that post-digestion islet size and size distribution were not included. It would be ideal to analyze islet size distribution in both the post-digestion and post-purification products, as the islet purification process can potentially change islets size through cellular edema and purification media toxicity. We believe that due to the impurity (1–2%) of the post-digestion sample, it is prone to islet counting errors and sampling bias, therefore it was not included in the analysis.

To our knowledge this is the first analysis of factors that impact islet size distribution in addition to islet yield. We used an analytical method new to the field and found that donor BMI, CIT, and collagenase were the most significant factors in determining islet outcomes.

Figure 5. AIC frequencies within eight islet size groups stratified by collagenase used.

n = 276. p value < 0.01 is considered statistically significant, with Sigma as the reference group.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank the UIC-COM (University of Illinois at Chicago College of Medicine) human islet team for providing technical assistance and the Chicago Diabetes Project (CDP; http://www.chicagodiabetesproject.org).

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CIT

Cold ischemia time

- Preserv.soln

Preservation solution

- Dig.time

Digestion time

- Dig.rate

Digestion rate

- AIC

Actual islet count

- AIC (log)

AIC log transformed

- IEq/g

IEq per gram digested pancreas tissue

- IEq/g (log)

IEq/g log transformed

References

- 1.Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, Korbutt GS, Toth E, Warnock GL, Kneteman NM, Rajotte RV. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med; 2000;343(4):230–238. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ricordi C, Gray DW, Hering BJ, Kaufman DB, Warnock GL, Kneteman NM, Lake SP, London NJ, Socci C, Alejandro R, et al. Islet isolation assessment in man and large animals. Acta Diabetol Lat; 1990;27(3):185–195. doi: 10.1007/BF02581331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lehmann R, Zuellig RA, Kugelmeier P, Baenninger PB, Moritz W, Perren A, Clavien PA, Weber M, Spinas GA. Superiority of small islets in human islet transplantation. Diabetes; 2007;56(3):594–603. doi: 10.2337/db06-0779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keymeulen B, Gillard P, Mathieu C, Movahedi B, Maleux G, Delvaux G, Ysebaert D, Roep B, Vandemeulebroucke E, Marichal M, In ‘t Veld P, Bogdani M, Hendrieckx C, Gorus F, Ling Z, van Rood J, Pipeleers D. Correlation between beta cell mass and glycemic control in type 1 diabetic recipients of islet cell graft. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A; 2006;103(46):17444–17449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608141103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lembert N, Wesche J, Petersen P, Doser M, Becker HD, Ammon HP. Areal density measurement is a convenient method for the determination of porcine islet equivalents without counting and sizing individual islets. Cell Transplant; 2003;12(1):33–41. doi: 10.3727/000000003783985214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchwald P, Wang X, Khan A, Bernal A, Fraker C, Inverardi L, Ricordi C. Quantitative assessment of islet cell products: estimating the accuracy of the existing protocol and accounting for islet size distribution. Cell Transplant; 2009;18(10):1223–1235. doi: 10.3727/096368909X476968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Niclauss N, Sgroi A, Morel P, Baertschiger R, Armanet M, Wojtusciszyn A, Parnaud G, Muller Y, Berney T, Bosco D. Computer-assisted digital image analysis to quantify the mass and purity of isolated human islets before transplantation. Transplantation; 2008;86(11):1603–1609. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31818f671a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kissler HJ, Niland JC, Olack B, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, Naji A, Kandeel F, Oberholzer J, Fernandez L, Contreras J, Stiller T, Sowinski J, Kaufman DB. Validation of methodologies for quantifying isolated human islets: an Islet Cell Resources study. Clin Transplant. 24(2):236–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01052.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacGregor RR, Williams SJ, Tong PY, Kover K, Moore WV, Stehno-Bittel L. Small rat islets are superior to large islets in in vitro function and in transplantation outcomes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290(5):E771–779. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00097.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fujita Y, Takita M, Shimoda M, Itoh T, Sugimoto K, Noguchi H, Naziruddin B, Levy MF, Matsumoto S. Large human islets secrete less insulin per islet equivalent than smaller islets in vitro. Islets. 3(1):1–5. doi: 10.4161/isl.3.1.14131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nam KH, Yong W, Harvat T, Adewola A, Wang S, Oberholzer J, Eddington DT. Size-based separation and collection of mouse pancreatic islets for functional analysis. Biomed Microdevices. 12(5):865–874. doi: 10.1007/s10544-010-9441-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gangemi A, Salehi P, Hatipoglu B, Martellotto J, Barbaro B, Kuechle JB, Qi M, Wang Y, Pallan P, Owens C, Bui J, West D, Kaplan B, Benedetti E, Oberholzer J. Islet transplantation for brittle type 1 diabetes: the UIC protocol. Am J Transplant; 2008;8(6):1250–1261. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ricordi C, Lacy PE, Finke EH, Olack BJ, Scharp DW. Automated method for isolation of human pancreatic islets. Diabetes; 1988;37(4):413–420. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.4.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbaro B, Salehi P, Wang Y, Qi M, Gangemi A, Kuechle J, Hansen MA, Romagnoli T, Avila J, Benedetti E, Mage R, Oberholzer J. Improved human pancreatic islet purification with the refined UIC-UB density gradient. Transplantation; 2007;84(9):1200–1203. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000287127.00377.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ponte GM, Pileggi A, Messinger S, Alejandro A, Ichii H, Baidal DA, Khan A, Ricordi C, Goss JA, Alejandro R. Toward maximizing the success rates of human islet isolation: influence of donor and isolation factors. Cell Transplant; 2007;16(6):595–607. doi: 10.3727/000000007783465082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nano R, Clissi B, Melzi R, Calori G, Maffi P, Antonioli B, Marzorati S, Aldrighetti L, Freschi M, Grochowiecki T, Socci C, Secchi A, Di Carlo V, Bonifacio E, Bertuzzi F. Islet isolation for allotransplantation: variables associated with successful islet yield and graft function. Diabetologia; 2005;48(5):906–912. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1725-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsumoto S, Zhang G, Qualley S, Clever J, Tombrello Y, Strong DM, Reems JA. Analysis of donor factors affecting human islet isolation with current isolation protocol. Transplant Proc; 2004;36(4):1034–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briones RM, Miranda JM, Mellado-Gil JM, Castro MJ, Gonzalez-Molina M, Cuesta-Munoz AL, Alonso A, Frutos MA. Differential analysis of donor characteristics for pancreas and islet transplantation. Transplant Proc; 2006;38(8):2579–2581. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanley SC, Paraskevas S, Rosenberg L. Donor and isolation variables predicting human islet isolation success. Transplantation; 2008;85(7):950–955. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181683df5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salehi P, Hansen MA, Avila JG, Barbaro B, Gangemi A, Romagnoli T, Wang Y, Qi M, Murdock P, Benedetti E, Oberholzer J. Human islet isolation outcomes from pancreata preserved with Histidine-Tryptophan Ketoglutarate versus University of Wisconsin solution. Transplantation; 2006;82(7):983–985. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000232310.49237.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brandhorst H, Brandhorst D, Hering BJ, Federlin K, Bretzel RG. Body mass index of pancreatic donors: a decisive factor for human islet isolation. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1995;103(Suppl 2):23–26. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1211388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Paushter D, Wang S, Barbaro B, Harvat T, Danielson K, Kinzer K, Zhang L, Qi M, Oberholzer J. Highly Purified versus Filtered Crude Collagenase: Comparable Human Islet Isolation Outcomes. Cell Transplant. doi: 10.3727/096368911X564994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]