Abstract

♦ Background: Hospitalization rates are a relevant consideration when choosing or recommending a dialysis modality. Previous comparisons of peritoneal dialysis (PD) and hemodialysis (HD) have not been restricted to individuals who were eligible for both therapies.

♦ Methods: We conducted a multicenter prospective cohort study of people 18 years of age and older who were eligible for both PD and HD, and who started outpatient dialysis between 2007 and 2010 in four Canadian dialysis programs. Zero-inflated negative binomial models, adjusted for baseline patient characteristics, were used to examine the association between modality choice and rates of hospitalization.

♦ Results: The study enrolled 314 patients. A trend in the HD group toward higher rates of hospitalization, observed in the primary analysis, became significant when modality was treated as a time-varying exposure or when the population was restricted to elective outpatient starts in patients with at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care. Cardiovascular disease, infectious complications, and elective surgery were the most common reasons for hospital admission; only 23% of hospital stays were directly related to complications of dialysis or kidney disease.

♦ Conclusions: Efforts to promote PD utilization are unlikely to result in increased rates of hospitalization, and efforts to reduce hospital admissions should focus on potentially avoidable causes of cardiovascular disease and infectious complications.

Keywords: Hemodialysis, hospitalization

People with kidney failure have a high burden of comorbid illness (1) and consume a disproportionate share of resources (2,3), including hospital beds (4-14). Hospitalization rates are a relevant consideration when choosing or recommending a dialysis modality, because those rates affect quality of life for patients (15,16), inform resource allocation (for example, the number of inpatient beds earmarked for a dialysis program), and influence the cost of caring for the dialysis population (2).

The data about relative rates of hospitalization for people treated with peritoneal dialysis (PD) and hemodialysis (HD) are conflicting (4-14). Given that many jurisdictions around the world are promoting PD and that a randomized comparison is not likely to be successful, efforts to reduce bias in observational studies are important. Previous analyses have not been restricted to individuals who are eligible for both PD and HD, and yet those patients are the ones who face a choice between the two modalities in clinical practice. In addition, although studies have reported the diagnoses most responsible for hospital stays (the conditions that contribute most to the length of stay), that parameter does not necessarily reflect the reason for admission to hospital and might not inform efforts to prevent hospitalizations. Finally, patients who start dialysis urgently in hospital are treated preferentially with HD. Inclusion of the initial hospitalization may bias analyses against HD (17).

The primary objective of the present study was to compare rates of hospitalization in incident dialysis patients treated with PD or with HD who were eligible for both therapies. Secondary objectives included describing the reasons for admission to hospital and determining the proportions of admissions that were dialysis-related, related to complications of kidney disease, and unrelated to dialysis or to complications of kidney disease. In addition, to further isolate the impact of modality on outcomes and to minimize bias, the analysis was restricted to patients who started dialysis electively as outpatients.

Methods

Design and Setting

Our multicenter prospective cohort study enrolled patients new to dialysis at facilities in Canada (Manitoba Renal Program, Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, London Health Sciences Centre, and Halton Healthcare Services). Research ethics board approval was obtained at all participating sites, and the reporting of the study follows published guidelines (18).

Data Management

All data were collected prospectively using a common, centrally hosted, web-based data collection platform. All users underwent a training program, and data elements were explicitly defined. Two experts (RRQ, MJO) reviewed all data for accuracy and consistency in coding. Queries were resolved before data analysis.

Patient Population

All individuals 18 years of age and older who started outpatient dialysis between 1 July 2007 and 30 April 2010 were captured across the four Canadian dialysis facilities, and all patients were followed for a minimum of 6 months. The study population was restricted to patients who were considered eligible for both HD and PD as determined by a multidisciplinary team at each program [detailed in a previous publication (19)].

Dialysis Treatment Modality

For the primary analysis, patients were assigned to the PD or the HD group based on the treatment modality in use at the time they initiated outpatient dialysis. When patients started dialysis in hospital, they were assigned to a group based on the first outpatient treatment modality at the time of discharge, and they were followed from that point forward. In the secondary, as-treated analysis, time at risk and outcomes were assigned to the current treatment modality. In that analysis, patients could contribute time to both the PD and the HD groups over the course of follow-up (dialysis modality treated as a time-varying exposure).

Outcomes

The data collected for all hospital admissions included admission date, discharge date, reason for admission, and length of stay. Two reviewers blinded to the dialysis modality (RRQ, MJO) used the primary reason for admission to classify the hospitalizations as dialysis-related, related to a complication of kidney disease but not to dialysis, or unrelated to dialysis or kidney disease. Hospitalizations were further classified as a complication of dialysis access, an urgent surgical intervention, or an admission resulting in death.

An admission was considered dialysis-related if it was a direct consequence of dialysis treatment or the need for dialysis access. This category also included hospitalizations for access-related complications and surgeries and for hypotension or dysrhythmias that occurred during or immediately after dialysis. Admissions related to complications of kidney disease included those for volume overload, electrolyte disturbances, and parathyroidectomy. The primary outcome of interest was the rate of hospitalization expressed as the number of hospital days per patient-year of follow-up. Patients were followed from the start of outpatient dialysis until death, kidney transplantation, loss to follow-up, or the end of the study period (4 November 2010).

Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient characteristics were compared between the PD and HD groups using the Fisher exact test for categorical variables and two-sided independent-sample t-tests or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables, as appropriate.

In the primary analysis, regression models for count outcomes were used to compare rates of hospitalization in the PD and HD groups, incorporating an offset variable to account for varying lengths of follow-up. The primary analysis reflected the impact of the initial outpatient treatment modality on rates of hospitalization. To address the excess of zero counts and the presence of overdispersion in the data, we used a zero-inflated negative binomial model. In that model, the probability of zero counts beyond the Poisson distribution was assumed to follow the binomial distribution (zero vs non-zero count), and the extra-Poisson variation was modeled assuming a negative binomial distribution (20). We assessed goodness of fit using information criteria, formal tests (likelihood ratio test and Vuong test), and checks of the agreement between observed and expected counts (20).

Zero-inflated models produce two estimates: an odds ratio for the likelihood of remaining hospitalization-free and a rate ratio for the count portion of the model. To present this information as a single estimate of effect that is comparable to a Poisson or negative binomial model, we used the final models to calculate the expected hospitalization rates for each individual: one assuming treatment with HD, and the other assuming treatment with PD. The mean value obtained assuming treatment with HD was divided by the mean value obtained assuming treatment with PD to produce an estimate of the rate ratio. Standard errors were estimated using bootstrapping techniques (21).

Predictor variables were screened for multi-collinearity, and all analyses were adjusted for known predictors of hospitalization rates: age, sex, the presence of diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate, serum albumin, history of gastrointestinal bleeding, receipt of at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care, and hospital start of dialysis (before a first outpatient dialysis treatment) (4-14). We accounted for clustering of patients within programs by using robust variance in our final models (20). We screened for outliers and repeated the analyses without them to see if the change materially affected our conclusions. To exclude urgent dialysis starts and to further isolate the influence of treatment modality on outcomes, the analysis was then repeated with the population restricted to people who had started dialysis electively, as outpatients, with at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care (17).

In a secondary, “as-treated” analysis, we used the same approach, but defined treatment modality as a time-varying exposure. This analysis reflected the impact of dialysis treatment modality on rates of hospitalization. Patients could contribute to both treatment groups if they spent time on both PD and HD. Robust variance was used to account for clustering of treatment periods within individual patients, and dialysis program was included as a covariate in the models.

Rates of hospitalization, expressed as the number of admissions per patient-year of follow-up, were also calculated according to modality and reason for admission. Finally, the daily expected hospital beds for every 100 patients who chose HD or PD was calculated by summing the expected number of hospital days per year in each group and dividing by 365.

Results

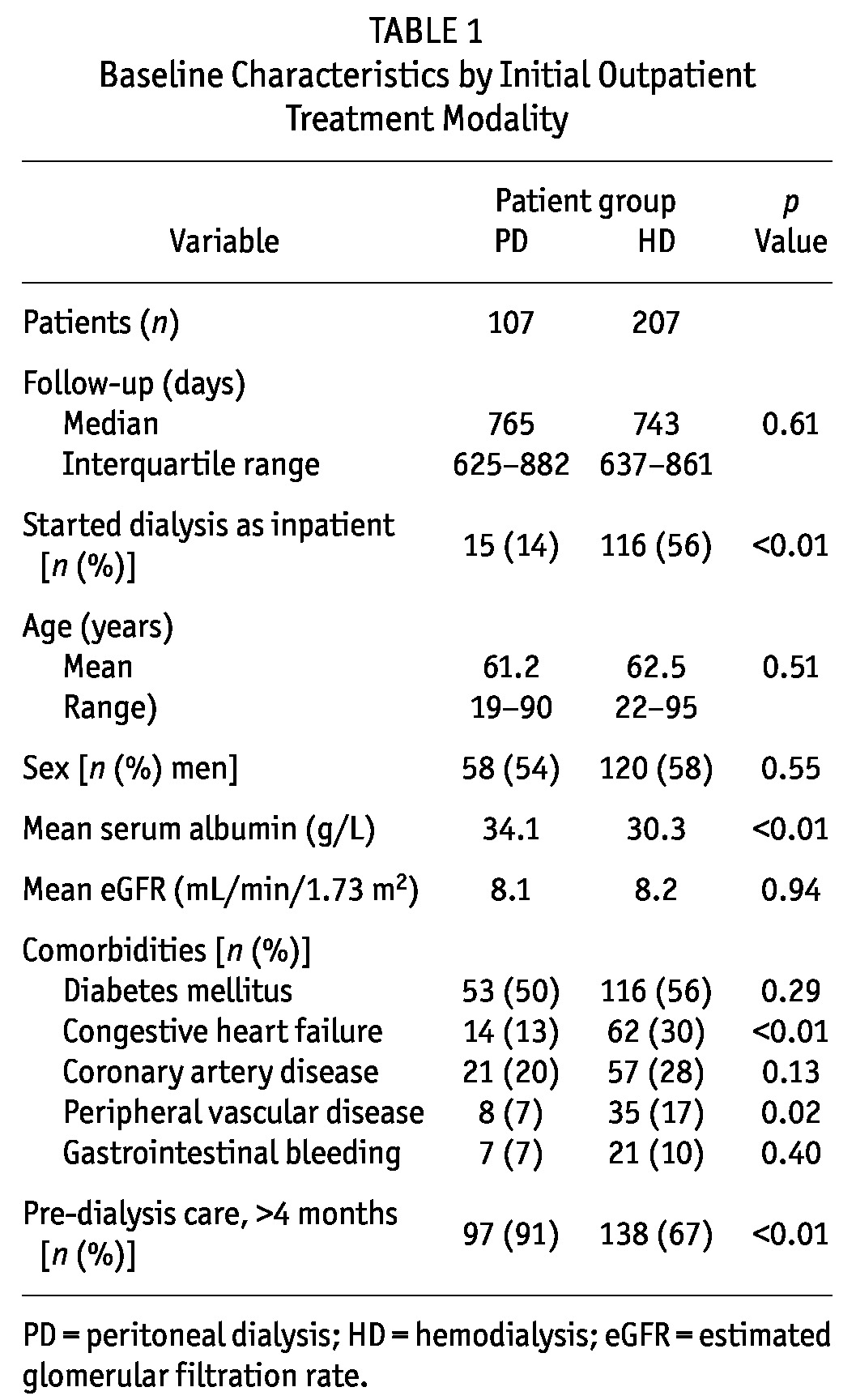

The 314 patients who met the study inclusion criteria contributed 597 patient-years of follow-up. First out-patient treatment modality was PD in 34% of patients (n = 107) and HD in 66% (n = 207). Table 1 shows baseline patient characteristics by treatment group. The patients starting with PD had higher serum albumin and were more likely to have received at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care. They were also less likely to have a history of congestive heart failure or peripheral vascular disease or to have started dialysis in hospital. Median follow-up was similar in both groups (765 days in the PD group vs 743 days in the HD group).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics by Initial Outpatient Treatment Modality

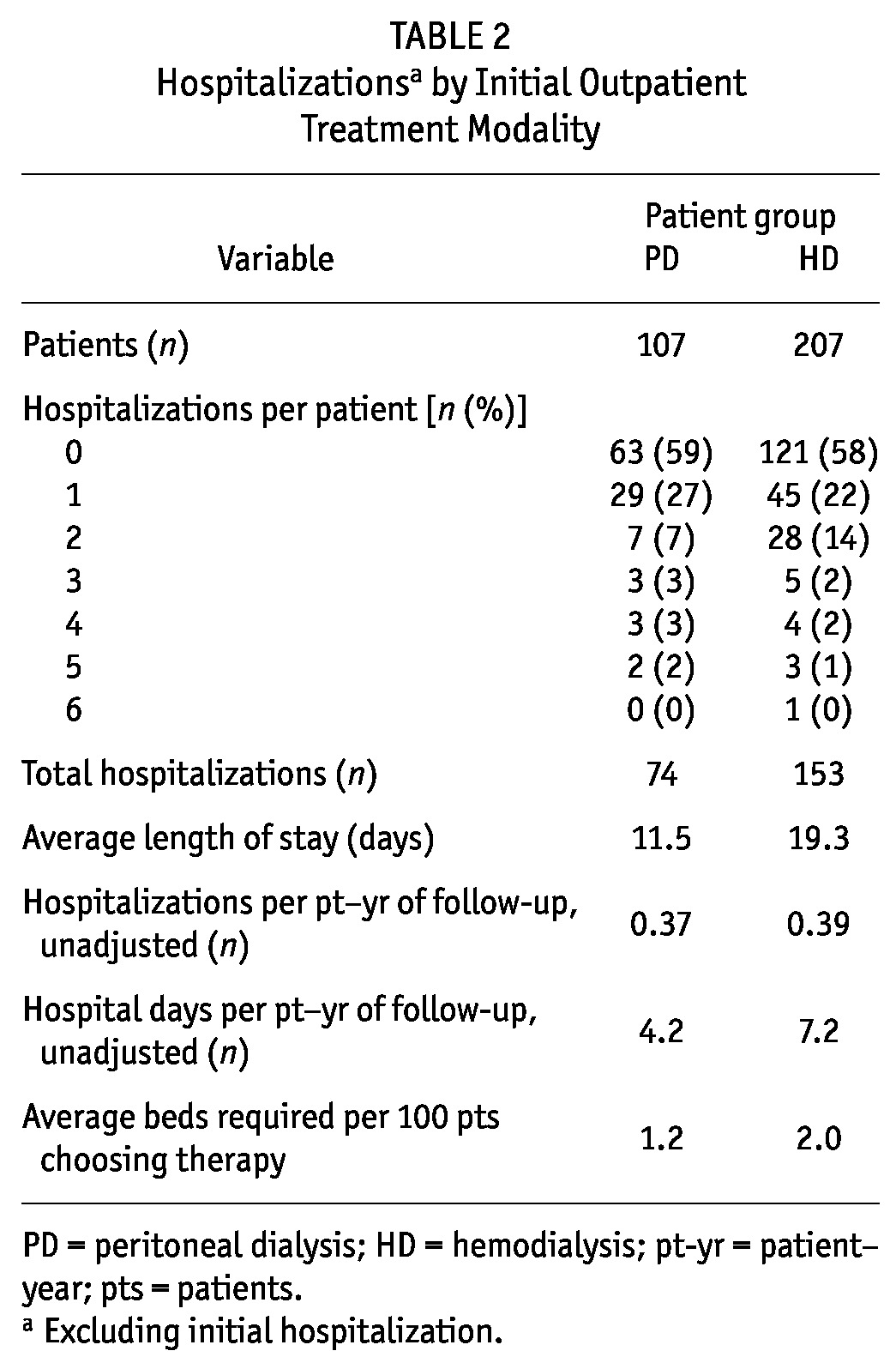

Of the 314 patients, 184 (59%) experienced at least 1 hospitalization during follow-up. The PD patients experienced a mean of 0.4 hospitalizations, for an average of 4.2 days in hospital per patient-year of follow-up. The HD patients also had a mean of 0.4 hospitalizations, but averaged 7 days in hospital per patient-year of follow-up. Average length of stay was 12 days in the PD group compared with 19 days in the HD group (p = 0.13, Table 2). Based on crude hospitalization rates for individuals eligible for both therapies, we estimated that 1.2 beds would be required for every 100 incident patients who chose PD and 2.0 beds would be required for every 100 incident patients who chose HD.

TABLE 2.

Hospitalizationsa by Initial Outpatient Treatment Modality

During follow-up, 20% of the cohort died (18% in the HD group, 22% in the PD group), and 23 hospitalizations ended in death (6% of all admissions). Transfers to another program, kidney transplantation, and recovery of kidney function occurred in 3%, 3%, and 1% of patients respectively.

In the primary intention-to-treat analysis, the rate of hospitalization was not statistically different in patients treated with HD and with PD (adjusted rate ratio: 1.21; 95% confidence limits: 0.55, 2.66), although the hospitalization rate trended higher in the HD group. In the secondary, as-treated, analysis, the rate of hospitalization was nonsignificantly higher for HD patients than for PD patients (adjusted rate ratio: 1.28; 95% confidence limits: 0.63, 2.61). When the analysis was restricted to elective outpatient dialysis starts in patients who had received at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care, the rate of hospitalization was significantly higher for those on HD than for those on PD in the intention-to-treat (adjusted rate ratio: 2.22; 95% confidence limits: 1.09, 4.53), but not in the as-treated analysis (adjusted rate ratio: 2.25; 95% confidence limits: 0.85, 5.97).

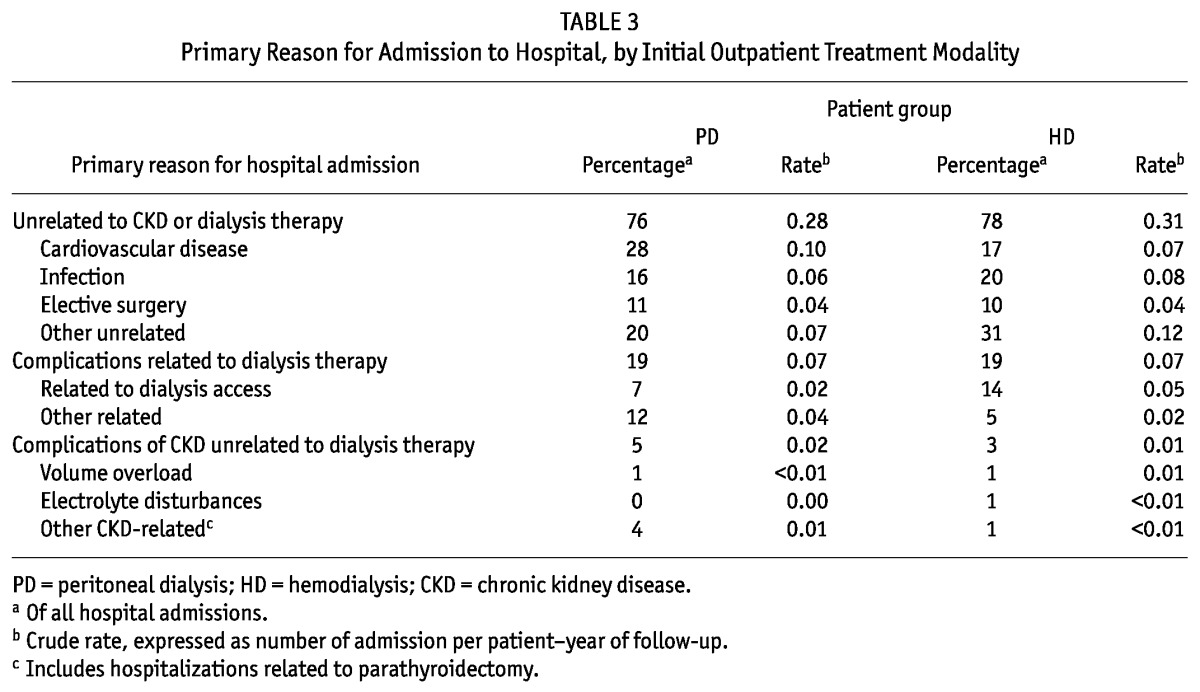

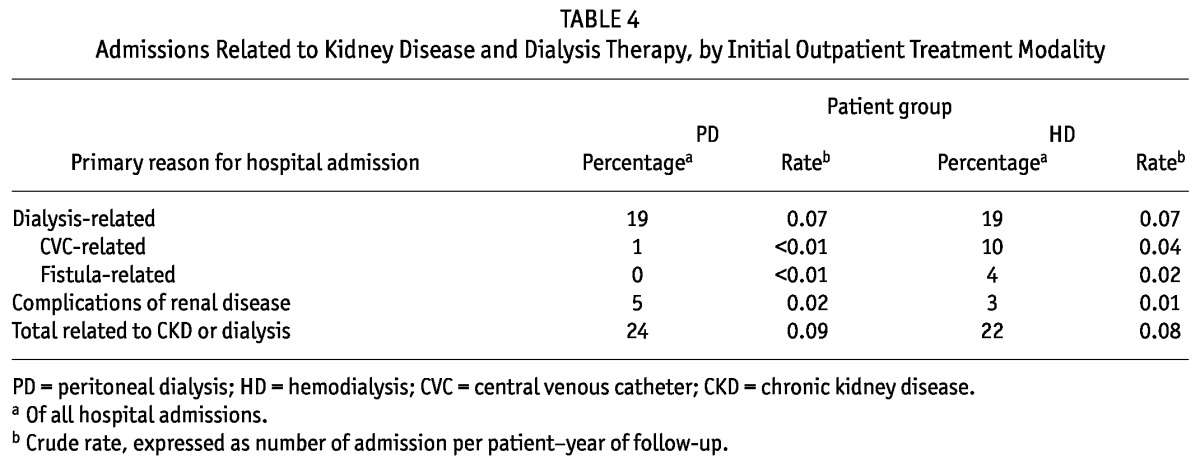

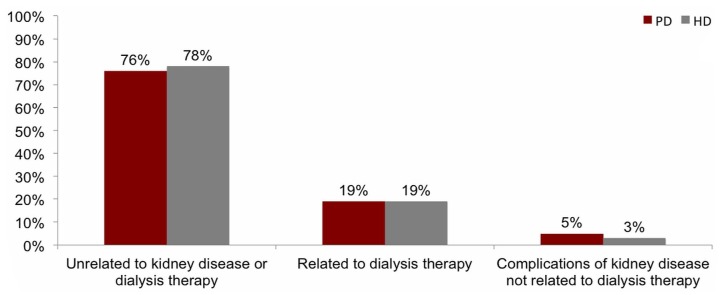

Tables 3 and 4 present the most common reasons for admission to hospital and the annualized admission rates by treatment modality. Most hospital admissions (77%) were for reasons unrelated to dialysis or complications of kidney disease (Figure 1). Dialysis-related admissions and complications of kidney disease unrelated to dialysis accounted for 19% and 4% of hospital stays respectively. Cardiovascular complications (coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease, stroke and transient ischemic attacks, and other cardiac disorders) were responsible for 21% of admissions overall (28% in the PD group and 17% in HD group). At 19%, infectious complications unrelated to dialysis were the second most common reason for admission to hospital overall (16% in the PD group and 20% in HD group). Access-related infections (PD peritonitis and HD catheter-related bacteremia) were responsible for 7% of hospital admissions in both groups. Elective (11%) or urgent (4%) surgical intervention accounted for 14% of admissions.

TABLE 3.

Primary Reason for Admission to Hospital, by Initial Outpatient Treatment Modality

TABLE 4.

Admissions Related to Kidney Disease and Dialysis Therapy, by Initial Outpatient Treatment Modality

Figure 1 —

Primary reason for hospital admission, by initial outpatient dialysis treatment modality. Hospitalizations were classified based on the primary reason for admission: related to dialysis therapy, complications of kidney disease unrelated to dialysis therapy, or unrelated to kidney disease or dialysis therapy. In patients treated with peritoneal dialysis (PD) and hemodialysis (HD), most hospitalizations were unrelated to kidney disease or dialysis therapy. We observed no significant differences by modality in the proportion of admissions that fell into each category.

Discussion

Our study found no difference in the rates of hospitalization for incident PD and HD patients who had been eligible for both therapies and who were followed from initiation of outpatient dialysis. There was, however, a trend toward an increased rate of hospitalization in the HD group that became significant when the population was restricted to elective outpatient starts in patients who had received at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care. Of all hospital stays, most (77%) were unrelated to dialysis or complications of kidney disease. The most common reasons for admission were cardiovascular disease, infectious complications, and elective surgery. Finally, a significant proportion of patients were not hospitalized during follow-up, a finding that has implications for the statistical approach to analyzing hospitalization data.

In our study, the HD group showed a trend toward a higher relative rate of hospitalization, and the crude hospitalization rate was lower in both groups—7 days per patient-year in the HD group and 4 days per patient-year in the PD group—than had previously been described (4-7,9-14,22). We lacked information about the availability of inpatient beds and the threshold for admitting patients to hospital (or how the threshold varied by region and over time in our study and others). All of those factors might contribute to the observed differences. In addition, many earlier studies and reports included the initial hospitalization if patients started dialysis in hospital, which probably inflated hospitalization rates. The inclusion of a prevalent patient population may have had a similar effect, given that, as dialysis vintage increases, the burden of comorbidities and the likelihood of hospitalization could very well increase. Finally, no previous analyses have restricted the patient population to individuals who were eligible for both PD and HD. Such a population may be healthier and less likely to be hospitalized.

It is not clear why restricting the analysis to patients who started dialysis electively as outpatients and who had at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care led to a much higher adjusted relative rate of hospitalization among HD patients. Our initial hypothesis was that the inclusion criteria would tend to bias our results toward a finding of no difference between dialysis modalities, rather than an accentuated difference. One potential explanation is that, in the adjusted analyses, starting dialysis in hospital was protective. In other words, patients who started dialysis in hospital and survived to hospital discharge had a lower likelihood of subsequent hospitalization compared with patients who started as outpatients. It may be that, in reaching discharge after an urgent start, patients who had issues with dialysis access were more likely to have those issues addressed before leaving hospital and to have the opportunity for an in-depth review of other medical issues, reducing the need for hospitalization in the ensuing months. Confirmation of that hypothesis in a larger cohort is required.

Most earlier studies did not explicitly report the proportion of hospital admissions related to the dialysis procedure, the need for dialysis access, or complications of kidney disease. Murphy et al. reported that dialysis-related hospitalizations were responsible for 10 hospital days per 1000 patient-days of follow-up, or 23% of time in hospital (12). In a report from the Scottish Renal Registry, Metcalfe et al. reported that 46% of hospitalizations in the first year of dialysis were for dialysis-related reasons (23). Creation of an access for dialysis and PD training made up 17% of the admissions, procedures that typically occur on an outpatient basis in Canada. If those admissions are omitted from the analysis, 29% of admissions were for dialysis-related reasons. We found that dialysis-related complications were responsible for 19% of admissions. If complications of kidney disease such as volume overload and hyperkalemia were to be included, that proportion would increase to 23%. The proportion of hospitalizations for dialysis-related reasons appears to be relatively consistent across studies.

Our study has several strengths. First, we restricted the cohort to people who were eligible for both PD and HD as determined by a multidisciplinary team. That restriction makes our results better suited to informing modality selection than those coming from analyses that include the 30% - 35% of patients who may not be eligible for both therapies. Second, high-quality data and detailed information about admissions allowed us to identify the reason that a person was hospitalized, rather than the diagnosis most responsible. The most responsible diagnosis is the condition that contributes most to length of stay and is not necessarily the reason that a patient was admitted to hospital. If the ultimate goal is to prevent hospitalizations, it is important to understand the reason that the patient initially presented. Third, our primary analysis focused on the rate of hospitalization in patients who were starting outpatient dialysis. Patients who start dialysis in hospital for urgent indications tend to be sicker and are preferentially treated with HD. By excluding the initial hospital stay, we attempted to level the playing field. In a further sensitivity analysis, we restricted the cohort to those starting dialysis electively as outpatients, with at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care (17).

Our study also has several limitations. First, although a focus on the eligible population better informs modality selection, observed hospitalization rates were lower than would be expected in the broader dialysis population. As a consequence, studies of prevalent patients probably provide a more accurate estimate of the total number of hospital days or hospital beds required by a typical dialysis program. Second, eligibility is subjective, and rates vary from center to center. However, no criteria for eligibility have been universally accepted, which reflects real-world practice. Third, the people who adjudicated the reason for admission were not blinded to treatment assignment, and the process was somewhat subjective. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to regions or countries in which PD utilization or the availability of inpatient beds differs from that in the programs participating in our study.

The findings of the present study have important clinical, research, and policy implications. From a clinical perspective, the results inform decision-making for modality selection and the likely impact of efforts to expand PD utilization in dialysis programs. It appears that promoting PD would not result in an increase in rates of hospitalization; in fact, use of PD might be associated with fewer hospital days. It has previously been shown that PD is associated with a lower risk of invasive, access-related procedures (24) and that mortality is not different between HD and PD (17). The fact that most hospitalizations were unrelated to dialysis or renal disease suggests that strategies to prevent hospitalizations or to reduce the length of stay should probably focus on the prevention and management of cardiovascular disease and infections. It is not clear how many hospital admissions in dialysis patients are potentially avoidable or where efforts to reduce the burden of hospitalization should be focused. In addition, hospitalization rates as a measure of the quality of care in dialysis programs should be interpreted with caution because admissions for elective surgery and illnesses unrelated to dialysis are common.

Conclusions

In summary, rates of hospitalization in our primary analysis were not different for incident PD and HD patients who had been eligible for both therapies. However, among patients treated with HD, we did observe a trend toward higher rates of hospitalization that became significant when the population was restricted to elective outpatient starts in patients who had received at least 4 months of pre-dialysis care. Most hospital stays were unrelated to complications of the dialysis procedure, dialysis access, or underlying renal disease. Efforts to reduce hospitalization should focus on potentially avoidable causes of cardiovascular disease and on infection-related illness. Because the study population was restricted to patients eligible for both HD and PD, the results are better able to inform modality selection in individuals who are faced with a choice between those modalities in clinical practice.

Disclosures

AXG was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Clinician-Scientist Award and received an unrestricted research grant from Fresenius Medical Care Canada. RRQ and MJO are co-inventors of the Dialysis Measurement, Analysis, and Reporting (DMAR) system. The DMAR platform was used to collect data for this study. RRQ was supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research during the study. PCA is the recipient of a Career Investigator Award from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario.

Acknowledgments

The Physician Services Foundation, Incorporated, funded the Ontario portion of this study.

References

- 1. Quinn RR, Laupacis A, Hux JE, Oliver MJ, Austin PC. Predicting the risk of 1-year mortality in incident dialysis patients: accounting for case-mix severity in studies using administrative data. Med Care 2011; 49:257–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee H, Manns B, Taub K, Ghali WA, Dean S, Johnson D, et al. Cost analysis of ongoing care of patients with end-stage renal disease: the impact of dialysis modality and dialysis access. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 40:611–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Vecchi AF, Dratwa M, Wiedemann ME. Healthcare systems and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) therapies—an international review: costs and reimbursement/funding of ESRD therapies. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14(Suppl 6):31–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bovbjerg RR, Diamond LH, Held PJ, Pauly MV. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis: preliminary evidence in the debate over efficacy and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 1983; 2:96–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carlson DM, Duncan DA, Naessens JM, Johnson WJ. Hospitalization in dialysis patients. Mayo Clin Proc 1984; 59:769–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gokal R, Jakubowski C, King J, Hunt L, Bogle S, Baillod R, et al. Outcome in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis: 4-year analysis of a prospective multicentre study. Lancet 1987; 2:1105–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burton PR, Walls J. A selection adjusted comparison of hospitalization on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1989; 42:531–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Williams AJ, Nicholl JP, el Nahas AM, Moorhead PJ, Plant MJ, Brown CB. Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis in the elderly. Q J Med 1990; 74:215–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singh S, Yium J, Macon E, Clark E, Schaffer D, Teschan P. Multicenter study of change in dialysis therapy-maintenance hemodialysis to continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 1992; 19:246–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Habach G, Bloembergen WE, Mauger EA, Wolfe RA, Port FK. Hospitalization among United States dialysis patients: hemodialysis versus peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995; 5:1940–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Charytan C, Spinowitz BS, Galler M. A comparative study of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis and center hemodialysis. Efficacy, complications, and outcome in the treatment of end-stage renal disease. Arch Intern Med 1986; 146:1138–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Murphy SW, Foley RN, Barrett BJ, Kent GM, Morgan J, Barré P, et al. Comparative hospitalization of hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients in Canada. Kidney Int 2000; 57:2557–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris SA, Lamping DL, Brown EA, Constantinovici N. on behalf of the North Thames Dialysis Study (NTDS) Group. Clinical outcomes and quality of life in elderly patients on peritoneal dialysis versus hemodialysis. Perit Dial Int 2002; 22:463–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. United States, Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, US Renal Data System (USRDS). 2008 Annual Data Report. 2 vols. Bethesda, MD: USRDS; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Evans RW, Manninen DL, Garrison LP, Jr, Hart LG, Blagg CR, Gutman RA, et al. The quality of life of patients with end-stage renal disease. N Engl J Med 1985; 312:553–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bremer BA, McCauley CR, Wrona RM, Johnson JP. Quality of life in end-stage renal disease: a reexamination. Am J Kidney Dis 1989; 13:200–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quinn RR, Hux JE, Oliver MJ, Austin PC, Tonelli M, Laupacis A. Selection bias explains apparent differential mortality between dialysis modalities. J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 22:1534–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. on behalf of the STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370:1453–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oliver MJ, Garg AX, Blake PG, Johnson JF, Verrelli M, Zacharias JM, et al. Impact of contraindications, barriers to self-care and support on incident peritoneal dialysis utilization. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2010; 25:2737–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Long JS, Freese J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata. 2nd ed. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Albert JM, Wang W, Nelson S. Estimating overall exposure effects for zero-inflated regression models with application to dental caries. Stat Methods Med Res 2011;:[Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Serkes KD, Blagg CR, Nolph KD, Vonesh EF, Shapiro F. Comparison of patient and technique survival in continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) and hemodialysis: a multicenter study. Perit Dial Int 1990; 10:15–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Metcalfe W, Khan IH, Prescott GJ, Simpson K, MacLeod AM. Can we improve early mortality in patients receiving renal replacement therapy? Kidney Int 2000; 57:2539–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oliver MJ, Verrelli M, Zacharias JM, Blake PG, Garg AX, Johnson JF, et al. Choosing peritoneal dialysis reduces the risk of invasive access interventions. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:810–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]