Editor:

A 48-year-old woman came for evaluation of abdominal pain with fever. She was a sausage factory employee, and her work involved stuffing raw pork into sausages. She had started automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) 2 years earlier for diabetic nephropathy. At presentation, she had diffuse abdominal pain, with turbid dialysate for 1 day.

Effluent leukocyte count was 8910/μL with 85% neutrophils. Intraperitoneal cefazolin and ceftazidime were given. The effluent culture finally grew Leclercia adecarboxylata, susceptible to all tested cephalosporins. Intraperitoneal ceftazidime was discontinued.

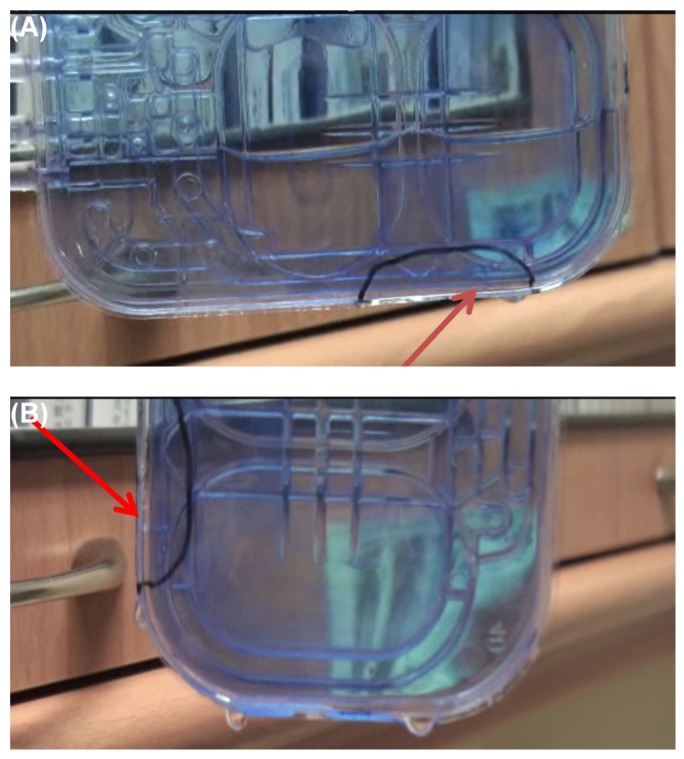

On further questioning, this patient reported intermittent observations of dialysate leakage from her cycler within the past 4 months. We discovered a hair-thin crack in the lower part of the cassette [Figure 1(A,B)]. On testing, the instilled fluid leaked slowly but continuously from the crack site. After exchange of the APD cassette, no further episodes of dialysate leakage occurred. Functional testing performed by the manufacturer on the cycler was normal, and the bacterial culture obtained from the cassette was persistently negative. We re-educated the patient about hand hygiene. She was discharged after a complete antibiotic course.

Figure 1 —

(A) Horizontal view of the cassette, lower part. The leakage site (hair-thin crack indicated by the arrow) is marked with a circle. (B) Vertical view of the cassette.

Leclercia adecarboxylata, a ubiquitous gram-negative rod, reportedly exists in the gut of animals (1-3). Infections caused by Leclercia adecarboxylata started to be recognized by microbiologists with advances in DNA hybridization techniques (2). However, the epidemiology of Leclercia adecarboxylata infections is still poorly defined because of the rarity of clinical reports (3). Most cases have been described in patients with post-traumatic wound infections or bacteremia (1,3,4) who were relatively immunosuppressed (5). In that sense, the immunosuppression conferred by end-stage renal disease might render peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients susceptible to Leclercia adecarboxylata infections.

Previous reports of PD peritonitis caused by Leclercia adecarboxylata did not describe the route of entry (2,6). In light of our patient’s job, her workplace and her main duty might expose her to cutaneous contamination with animal feces. We propose that this Leclercia adecarboxylata PD peritonitis is likely the result of a break in sterile exchange technique, with contamination of the dialysate. This is an important clinical finding that warrants further attention.

In this patient, we suspect that the peritonitis resulted from two components. First, a break in sterility is a concern, as already described. We thought that a review and re-education in exchange technique would be helpful in preventing a subsequent peritonitis episode. Second, the cassette leak might also play a role. Cycler cassette rupture is very rare in PD practice, and to the best of our knowledge, no such case has been reported in the literature. Most cases of device problems in PD patients involve catheter rupture (7-9), and the cassette is often ignored. Such a leak is an under-recognized cause of PD peritonitis, and in patients who develop PD peritonitis, it is important to seek unidentified mechanical factors as well as to provide education about proper hand hygiene.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Temesgen Z, Toal DR, Cockerill FR., 3rd Leclercia adecarboxylata infections: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1997; 25:79–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fattal O, Deville JG. Leclercia adecarboxylata peritonitis in a child receiving chronic peritoneal dialysis. Pediatr Nephrol 2000; 15:186–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hess B, Curchett A, Huntington MK. Leclercia adecarboxylata in an immunocompetent patient. J Med Microbiol 2008; 57:896–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fernández-Ruiz M, López-Medrano F, García-Sánchez L, García-Reyne A, Ortuño de Solo T, Sanz-Sanz F, et al. Successful management of tunneled hemodialysis catheter related bacteremia by Leclercia adecarboxylata without catheter removal: report of two cases. Int J Infect Dis 2009; 13:e517–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Longhurst CA, West DC. Isolation of Leclercia adecarboxylata from an infant with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Infect Dis 2001; 32:1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rodríguez JA, Sánchez FJ, Gutiérrez N, García JE, García-Rodríguez JA. Bacterial peritonitis due to Leclercia adecarboxylata in a patient undergoing peritoneal dialysis [Spanish]. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2001; 19:237–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Agarwal S, Gandhi M, Kashyap R, Liebman S. Spontaneous rupture of a silicone peritoneal dialysis catheter presenting outflow failure and peritonitis. Perit Dial Int 2011; 31:204–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rao SP, Oreopoulos DG. Unusual complications of a polyurethane PD catheter. Perit Dial Int 1997; 17:410–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weaver ME, Dunbeck DE. Mupirocin (Bactroban) causes permanent structural changes in peritoneal dialysis catheters [Abstract]. Perit Dial Int 1994; 14(Suppl 1):S20 [Google Scholar]