Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to analyse the results of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in stiff knees (flexion ≤90° and/or flexion contracture ≥20°). Our hypothesis was that despite having poorer results than those obtained in a “standard” population and a high rate of complications, TKA was a satisfactory treatment in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee associated with significant stiffness.

Methods

Three hundred and four consecutive primary HLS TKAs (Tornier), whose data were prospectively collected between October 1987 and October 2012, were retrospectively analysed at a mean of 60 months (range, 12–239) postoperatively. Two groups, those with a “flexion contracture” and those with a “flexion deficit”, were assessed for postoperative range of motion (as integrated to the Knee Society score [KSS]), physical activity level and patient satisfaction.

Results

At the latest follow-up, range of motion was significantly improved, as was the KSS. Ninety-four percent of patients were satisfied or very satisfied, and activity levels were increased after surgery. The complication rate, however, was high in patients with a preoperative flexion deficit (17 %). Pain and residual stiffness were the most common complications.

Conclusion

TKA provides satisfactory results in patients with knee osteoarthritis associated with significant pre-operative stiffness. The surgical plan should be adapted to anticipate complications, which are particularly frequent in the presence of a flexion deficit.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty, Stiffness, KSS, Surgical strategy

Introduction

The main objectives of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are to achieve a well-aligned, stable, mobile and painless knee. These objectives are achieved in most patients, however, what happens to patients with osteoarthritis (OA) and significant pre-operative stiffness? The postoperative range of motion correlates generally with pre-operative range of motion [1, 2]. What range may we thus hope to achieve after surgery? What technical tricks can be used during surgery to regain satisfactory postoperative mobility? Is the risk of postoperative complications increased in these patients? Mobility is the second patient’s expectation after painless knee, so are they finally satisfied with our treatment?

To investigate these questions we analysed a series of 304 TKA performed between October 1987 and October 2012 in patients who had stiffness in flexion and/or in extension. Our hypothesis was that despite varying degrees of motion restriction compared with those obtained in a normal population, and a high rate of complications, TKA was a satisfactory therapeutic solution for patients with a stiff knee.

Materials and methods

Patients

Stiffness is usually defined as knee flexion of less than 90° and/or extension less than 0°. A moderate pre-operative flexion contracture, however, does not always require additional releases during surgery compared to the standard technique. We evaluated the results of patients with pre-operative flexion ≤90°, or loss of extension with a flexion contracture ≥20°.

Between October 1987 and October 2012, 239 patients with flexion of less than 90° and 65 patients with a flexion contracture greater than 20° underwent TKA at our institution. The results were assessed at a minimum follow-up of one year. The average follow-up was 60 months (range, 12–239).

Loss of flexion and loss of extension are managed differently in the peri-operative and postoperative periods. As such we analysed the results of these two groups separately.

Patients with flexion deficit (n = 239)

This group included 185 women (77 %) and 54 men (23 %). The average age was 69 years (range, 36–89) and the mean BMI was 29 (14–54). The indication for TKA was osteoarthritis in 206 cases (86 %), chronic inflammatory arthritis such as rheumatoid arthritis in 22 (9 %), condylar necrosis in four (2 %), and chondrocalcinosis in three (1 %).

In 107 cases (34 %) the knee had undergone previous surgery such as high tibial osteotomy, arthroscopy, meniscectomy, osteosynthesis, anterior tibial tuberosity (ATT) surgery, ligament surgery, synovectomy or arthrolysis. The femoro-tibial OA was predominantly medial in 82 %. The OA was considered primary in 79 %. One hundred twenty patients considered themselves sedentary (50 %), 83 were walking outside the house (35 %) and 35 (15 %) practised sports.

The mean pre-operative flexion was 83° (SD, 13), with a total range of motion of 75°. The average KSS pre-operative score was 33 for the knee score and 48 for the functional score.

Patients with pre-operative flexion contracture (n = 65)

This group included 41 women (63 %) and 24 men. The mean age was 68 years (40–88) and mean BMI was 28 (17–46). Indication for TKA was OA in 47 cases (72 %), chronic inflammatory arthritis in 14 (22 %), and condylar necrosis in two (3 %). In 22 cases (34 %) the knee had undergone previous surgery, the most common operation being osteosynthesis. Femoro-tibial osteoarthritis was predominantly medial in 40 cases (87 %). OA was considered primary in 37 cases (80 %) and post-traumatic in six cases (13 %), rarely after ligament injury.

The mean pre-operative flexion contracture was 25° (SD = 8). The average pre-operative range of motion averaged 69°. The average pre-operative KSS knee score was 22 and functional score was 51. Thirty three patients considered themselves sedentary (51 %), 21 were walking outside the house (32 %), and 11 practised sports (17 %).

Surgical technique

A posterior-stabilized, cobalt-chrome total knee prosthesis with patellar resurfacing was used in all cases (HLS implant, Tornier, Saint Ismier, France). The surgical technique was the standardized HLS [3]. The tibial cut was made first, followed by the posterior femoral and distal femoral cuts in an independent fashion. The incision depended on the pre-operative coronal plane alignment: para-medial incision for varus deformities, and para-lateral incision for valgus deformities. Pre existing scars were re-used. The implants were all cemented, except eight uncemented femoral components (3 %) implanted during a randomized prospective study. A tourniquet was used in 95 % of cases. The average operative time was 94 minutes (45–180).

Surgical strategy for flexion deficit

In this case, the approach is essential and must be planned according to the envisaged soft tissue release.

When the deficit of flexion was limited, a medial para-patellar approach was used in medial femoro-tibial OA (198 cases or 83 %) and a lateral para-patellar approach for lateral femoro-tibial OA (40 cases or 17 %). The approach is then completed by the release of the patellar tendon, the supra-patella pouch and the condylar recesses. When exposure is difficult after the arthrolysis, a “quad snip” may be used [4–6]. We do not perform the V-Y quadricepsplasty because of the high morbidity associated with this procedure [7, 8].

If these releases were insufficient to permit exposure, especially in case of patella infera, an ATT osteotomy was performed [9], here in 19 cases (8 %). In cases of patella infera, the osteotomy may be performed with a view to fixation in a more proximal position at the completion of surgery. If the origin of the pre-operative deficit of flexion is extra articular due to quadriceps adhesions, a release may be performed as described by Judet et al. [10] or by Lobenhoffer (resection of the vastus intermedius muscle) [11]. This is required only rarely in our experience.

The exposure can damage the tibial insertion of the patellar tendon. We insert a pin through this tendon insertion to protect it when performing this procedure; this artifice was borrowed from G Deschamps [3]. The procedure can be completed with release of the patella retinaculum medially and laterally.

Surgical strategy in flexion contracture

In our series, the surgical approach was medial in cases of medial femoro-tibial osteoarthritis (88 %) and lateral in cases of lateral femoro-tibial OA. Pre-existing scars were re-used when present. The exposure is generally easy when flexion is not significantly restricted, however, in one case of mixed stiffness an ATT osteotomy was necessary. Ligament releases were performed based on the coronal plane deformity. They must be generous enough behind the tibia to reduce the flexion contracture before performing bony cuts, including release of the semimembranosus tendon insertion medially and lateral capsular releases laterally.

Regarding the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), the presence of a pre-operative flexion contracture justifies sacrifice of the PCL and the use of a posterior-stabilized implant.

The posterior femoral release occurs after the posterior femoral cuts are made. Posterior osteophytes must be removed. We then release the posterior capsule from the condyles and the origin of the gastrocnemius on the femur with a rasp (25 cases or 38 %). The bone cuts must restore balanced and equal spaces in flexion and extension, as in any TKA. In the presence of a flexion contracture, the thickness of the bone cuts may be increased in order to recreate these spaces. This increase must be as small as possible to avoid creating laxity. In cases of flexion contracture, the extension gap is decreased, so one may begin by increasing the distal femoral cut. We rarely take more than an additional 2 mm to avoid altering the joint line. If this is inadequate, one may also increase the tibial cut, but this will also increase the flexion gap. In our series, the distal femoral cut was increased in 55 patients (85 %) and the tibial cut in 40 % of cases (26 patients).

Evaluation method

Range of motion was measured clinically pre- operatively and integrated to the KSS [12] (knee score and function score). Patients were then reassessed after surgery at two months, six months, one year and then every two years. A minimum of one year of follow-up was required to assess the final mobility. We clinically measured flexion, extension and total range of motion. Patient satisfaction was assessed subjectively, with patients self describing as very satisfied, satisfied, dissatisfied or disappointed. The type and the frequency of complications were collected, with and without revision. Radiographs were made at two months, one year and then every two years. All results were collected prospectively and analyzed retrospectively. Pre and postoperative values were compared using the Student t-test with a significant threshold defined at 0.05.

Results

The rate of intra-operative complications was relatively high in our series in the flexion deficit group (11 cases or 4.6 %) with six fractures of the tibia, two ruptures of the patellar tendon, one division of the popliteus tendon, one ATT fracture, and one case of impingement between the polyethylene and the patella after surgery. The intra-operative complication rate was low in the flexion contracture group with one tibial fracture and one division of the medial collateral ligament.

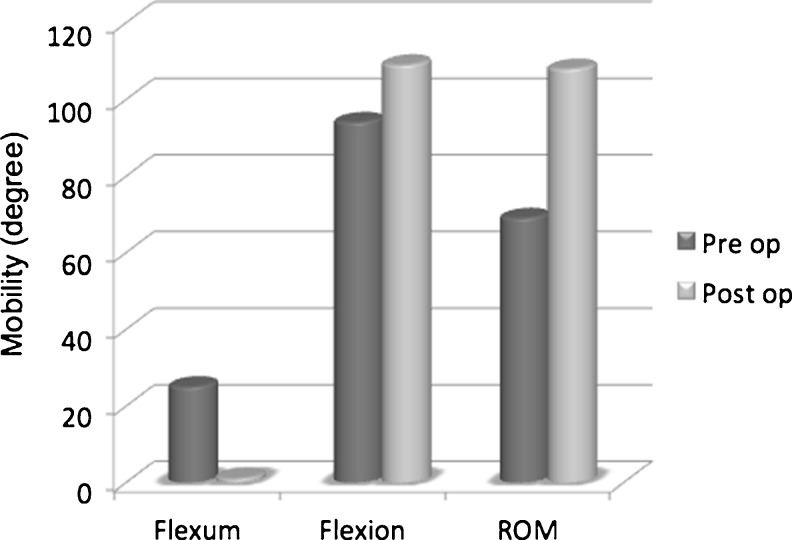

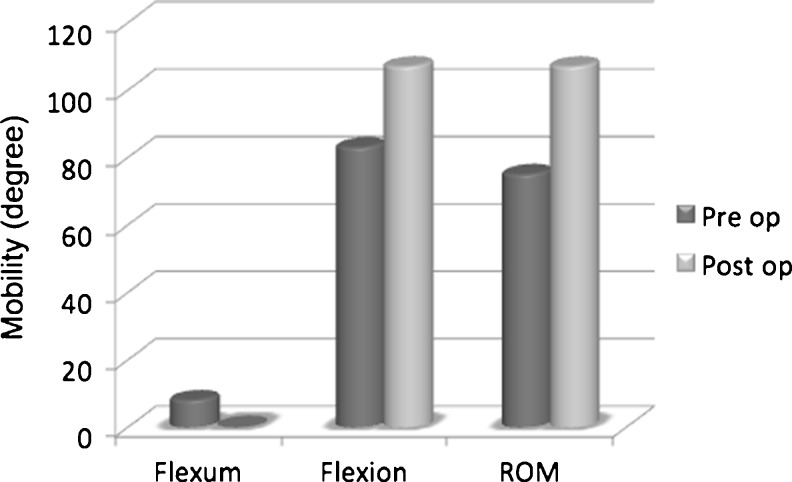

In both groups, range of motion was significantly improved with an average gain of 39° in the flexion contraction group (n = 65) and 32° in the flexion deficit group (n = 239) (p < 0.05) (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 1.

Mobility in the flexion contracture group

Fig. 2.

Mobility in the flexion deficit group

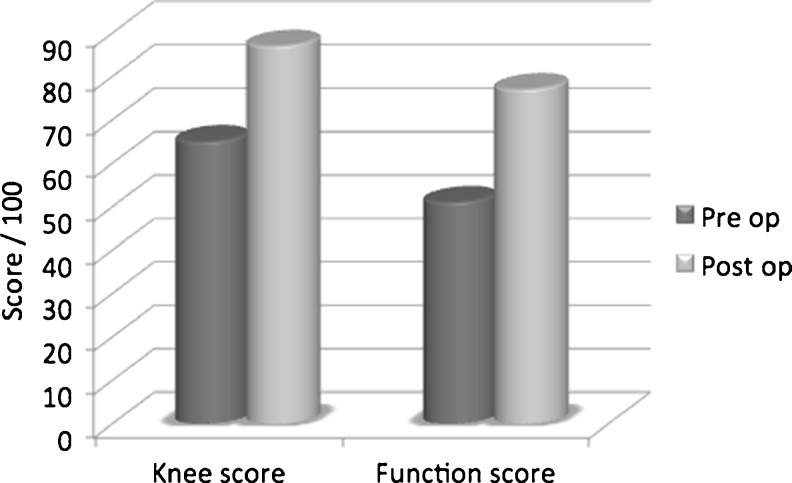

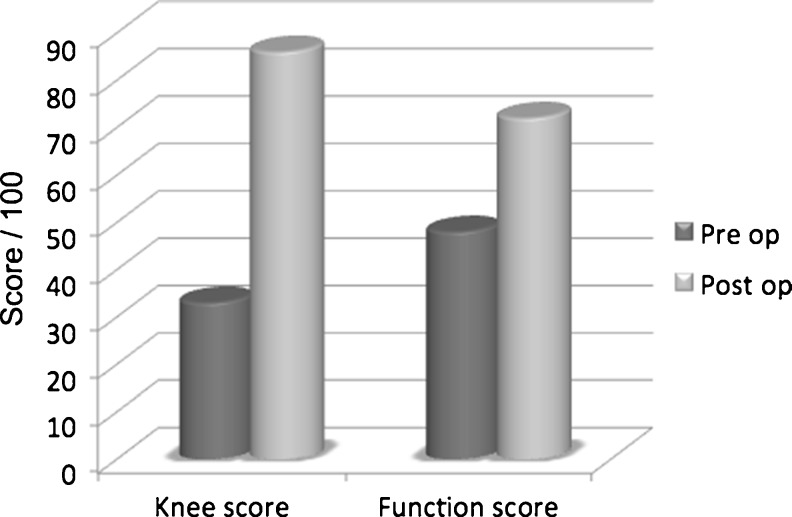

Regarding the KSS in the flexion contraction group, the knee score improved from 65 to 87 and the functional score from 51 to 77, which was significant (p < 0.05). In the flexion deficit group, the knee score improved from 33 to 86 and the functional score from 48 to 72, which was significant (p < 0.05) (Figs. 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

KSS in the flexion contracture group

Fig. 4.

KSS in the flexion deficit group

At most recent follow-up, 94 % were satisfied or very satisfied with the results of their TKA. Regarding activity levels, patients were significantly more active after surgery (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Activity levels before and after surgery

| Activity | Flexion contracture group | Flexion deficit group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre op | Post op | Pre op | Post op | |

| Sedentary | 51 % | 22 % | 50 % | 27 % |

| Walking | 32 % | 35 % | 35 % | 36 % |

| Sport | 17 % | 28 % | 15 % | 37 % |

Manipulation under anaesthesia was required in 4 % of cases in the flexion deficit group, at an average of 25 days postoperatively (ten to 50), and in one patient in the flexion contracture group 33 days after surgery. The postoperative complication rate was 6 % in the flexion contracture group (four cases) and 17 % in the flexion deficit group (40 cases) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Postoperative complications

| Complication | Flexion contraction group | Flexion deficit group | Revision |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stiffness | - | 16 | 7 |

| Pain | - | 4 | 1 |

| Sepsis | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| Skin necrosis | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Polyethylene wear | - | 1 | 1 |

| Patella fracture | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| ATT fracture | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Femoral fracture | - | 1 | 1 |

| Clunk | - | 2 | 2 |

| Laxity | - | 1 | 1 |

| Bone conflict | - | 1 | 1 |

| Implant fracture | - | 1 | 1 |

| Extensor mechanism rupture | - | 1 | 1 |

| Haematoma | - | 2 | - |

| Loosening | - | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 4 | 40 | 25 |

Discussion

The results of our analysis, one of the largest series in the literature with a significant follow-up, allows us to confirm that TKA performed in the setting of the stiff knee improves mobility, pain and patient satisfaction, as evidenced by the difference between pre and postoperative KKS scores, patient satisfaction after surgery and the resumption of sporting activities.

Regarding the follow-up, we decided to define the shorter follow-up at 12 months because we found that range of motion can be improved during the first postoperative year, but rarely after one year.

Regarding range of motion, the improvement observed in our series is similar to that reported in other series in the literature [13–17]. These ranges are lower than those that can be expected in a population with osteoarthritis of the knee without significant associated stiffness. Indeed, a study of our database in 2012, which analyzed the results of TKA by gender, showed an average flexion of 125° [18]. The mean flexion in our “flexion deficit” group reached 107°. Patient satisfaction in this group, however, is excellent and reflects a significant gain. Patient satisfaction is comparable to our overall series of 3,285 TKA reviewed in October 2012, with 94 % satisfied or very satisfied. These excellent results are moderated by a postoperative complication rate which remains high, especially in cases of limited pre-operative flexion. This observation is found in other series in the literature, focusing on the results of TKA in stiff or ankylosed knees [19–21]. Patients should be informed of these risks before the surgery in order to match their expectations and their satisfaction after surgery.

TKA in the stiff knee requires preoperative surgical planning and the use of a specific surgical strategy according to the type and the degree of stiffness. Our strategy includes pre-operative physiotherapy, use of a constrained implant in large deformities and a posterior-stabilized implant in all cases of flexion contracture, and finally the choice of approach. During the procedure, the surgical strategy depends on the kind of stiffness, e.g. in flexion deficits, it is the soft tissue releases during the approach and of the extensor mechanism which are essential, while in flexion contracture it is soft tissue releases and subsequent consideration of increased bone cut thicknesses. Some authors suggest increasing the thickness of the bone cuts with flexion contracture of 30° [22–24]; however, in our experience we do not hesitate to increase the thickness with flexion contractures of 10°, a strategy similar to that described by Bellemans [25]. Some procedures allow better exposure but increase the risk of postoperative complications (quads snip , ATT osteotomy, VY quadricepsplasty, Judet arthrolysis). Postoperatively, careful and prolonged rehabilitation is essential, as well as surveillance to detect complications. Manipulation under anaesthesia must be discussed in postoperative flexion deficits and performed with caution, as these patients are at increased risk of rupture of the extensor mechanism.

Conclusion

TKA is a therapeutic option that provides satisfactory results in patients with knee osteoarthritis associated with severe pre-operative stiffness in flexion or extension. It requires adaptation of the surgical strategy to anticipate complications, which are frequent, particularly in case of flexion deficit.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Frédéric Marcelli for his contribution in carrying out the statistical analysis.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Gatha NM, Clarke HD, Fuchs R, Scuderi GR, Insall JN. Factors affecting postoperative range of motion after total knee arthroplasty. Am J Knee Surg. 2004;17:196–202. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi MG, Lü HS, Guan ZP. Influence of preoperative range of motion on the early clinical outcome of total knee arthroplasty. Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2006;44(16):1101–1105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Neyret P, Demey G, Servien E, Lustig S. Traité de chirurgie du genou. Issy les Moulineaux: Elsevier Masson; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coonse K, Adams JD. A new operative approach to the knee joint. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1943;77:344–347. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garvin KL, Scuderi GS, Insall JN. Evolution of the quadriceps snip. Clin Orthop. 1995;321:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Insall JN. Chapter 3. Surgical approaches to the knee. In: Insall JN, editor. Surgery of the Knee. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1984. pp. 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trousdale RT, Hanssen AD, Rand JA, Cahalan TD. V-Y quadricepsplasty in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1993;286:48–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu CH, Lin PC, Chen WS, Wang JW. Total knee arthroplasty in patients with stiff knees. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(2):286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiteside LA. Exposure in difficult total knee arthroplasty using tibial tubercle osteotomy. Clin Orthop. 1995;321:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Judet R, Judet J, Lord G. Results of treatment of stiffness of the knee caused by arthrolysis and disinsertion of the quadriceps femoris. Mem Acad Chir (Paris) 1959;85:645–654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freiling D, Galla M, Lobenhoffer P. Arthrolysis for chronic flexion deficits of the knee. An overview of indications and techniques of vastus intermedius muscle resection, transposition of the tibial tuberosity and z-plasty of the patellar tendon. Unfallchirurg. 2006;109(4):285–296. doi: 10.1007/s00113-005-1039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop. 1989;248:13–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim Y-H, Kim J-S. Does TKA improve functional outcome and range of motion in patients with stiff knees ? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1348–1354. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0445-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhan S, Malhotra R, Kiran EK. Comparison of total knee arthroplasty in stiff and ankylosed knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;451:87–95. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000229313.20760.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winemaker M, Rahman WA, Petrucelli D, De Beer J. Preoperative knee stiffness and total knee arthroplasty outcomes. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8):1437–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montgomery WH, 3rd, Insall JN, Haas SB, Becker MS, Windsor RE. Primary total knee arthroplasty in stiff and ankylosed knees. Am J Knee Surg. 1998;11(1):20–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massin P, Lautridou C, Cappelli M. Total knee arthroplasty with limitations of flexion. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(suppl1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demey G, Hobbs H, Lustig S, Servien E, Trouillet F, Magnussen RA, et al. Influence of gender on the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. Eur Orthop Traumatol. 2013;3:11–16. doi: 10.1007/s12570-012-0094-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Massin P, Bonnin M, Paratte S, Vargas R, Piriou P, Deschamps G, The French Hip Knee Society (SFHG) Total knee replacement in post-traumatic arthritic knees with limitation of flexion. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2011;97:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bae DK, Yoon KH, Kim HS, Song SJ. Total knee arthroplasty in stiff knees after previous infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:333–336. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B3.15457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McAuley JP, Harrer MF, Ammeen D, Engh GA. Outcome of knee arthroplasty in patients with poor preoperative range of motion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:203–207. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schurman JR, Wilde AH. Total knee replacement after spontaneous osseus ankylosis. J Bone Joint Surg (A) 1990;72:455–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tew M, Forster IW. Effects of knee replacement on flexion deformity. J Bone Joint Surg (B) 1987;69:395–399. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.69B3.3584192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Judet H (2001) Prothèse sur genou raide: table ronde SOFCOT. Revue de Chirurgie Orthopédique 2001

- 25.Bellemans J, Vandenneucker H, Victor J, Vanlauwe J. Flexion contracture in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:78–82. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238791.36725.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]