Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to retrospectively compare the results of two matched-paired groups of patients who had undergone a medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) performed using either a conventional or a non-image-guided navigation technique specifically designed for unicompartmental prosthesis implantation.

Methods

Thirty-one patients with isolated medial-compartment knee arthritis who underwent an isolated navigated UKA were included in the study (group A) and matched with patients who had undergone a conventional medial UKA (group B). The same inclusion criteria were used for both groups. At a minimum of six months, all patients were clinically assessed using the Knee Society Score (KSS) and the Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) index. Radiographically, the frontal-femoral-component angle, the frontal-tibial-component angle, the hip-knee-ankle angle and the sagittal orientation of components (slopes) were evaluated. Complications related to the implantation technique, length of hospital stay and surgical time were compared.

Results

At the latest follow-up, no statistically significant differences were seen in the KSS, function scores and WOMAC index between groups. Patients in group B had a statistically significant shorter mean surgical time. Tibial coronal and sagittal alignments were statistically better in the navigated group, with five cases of outliers in the conventional alignment technique group. Postoperative mechanical axis was statistically better aligned in the navigated group, with two cases of overcorrection from varus to valgus in group B. No differences in length of hospital stay or complications related to implantation technique were seen between groups.

Conclusion

This study shows that a specifically designed UKA-dedicated navigation system results in better implant alignment in UKA surgery. Whether this improved alignment results in better clinical results in the long term has yet to be proven.

Keywords: Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, Computer-assisted

Introduction

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) remains a highly demanding and unforgiving surgical procedure, and the accuracy of implant alignment is an accepted prognostic factor for long-term implant survival [1–4]. Using conventional free-hand instrumentation for UKA implantation has led to rates of component malalignment as high as 30 % [5]. Authors show that coronal malalignment >3° and a tibial slope >7° increased the rate of aseptic failure in UKA more so than in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [6, 7]. Overcorrection in the coronal plane is also a well-recognised cause of UKA failure, as it can result in overloading of the contralateral compartment [3, 4]. Even the use of short, narrow intramedullary guides is ineffective in preventing UKA malalignment in different planes [8].

Many authors show that computer-assisted surgery can improve implant positioning in joint-replacement surgery without the need for intramedullary guides [9, 10]. Theoretically, this improvement in prosthesis alignment should lead to long-term reduction in the number of revisions. However, despite improved component alignment in TKA using navigation, no clear clinical advantages are demonstrated [11, 12]. More obvious clinical advantages may be expected in a more demanding surgery, such as the UKA, where traditional techniques can lead to poor alignment accuracy [13–16]. In fact, results of a recent meta-analysis suggest that despite longer surgical time, the use of a navigation system in UKA results in more accurate component positioning compared with the conventional implantation method [17]. However, the same study showed no clear clinical advantages of this improvement in component alignment [17]. The literature contains only a few studies that assess any further advantage from using computer navigation with a specifically UKA-dedicated software system in comparison with a conventional surgical technique for medial UKA [13, 18].

The aim of this matched paired study was to determine whether a purpose-designed navigation system results in better clinical and radiological outcomes at short-term follow-up than a conventional implantation technique for medial UKA.

Materials and methods

From January 2012 to May 2013, 31 patients with isolated medial-compartment knee arthritis who underwent navigated UKA were included in the study (group A). The first ten cases undertaken using this navigation technique were excluded from the study to avoid bias associated with the learning curve. Group B consisted of matched patients who had undergone a conventional UKA in our Institution for medial-compartment knee arthritis between August 2011 and May 2013. Patients were matched in terms of pre-operative arthritis grade, age (maximum difference, three years), gender and pre-operative range of motion (ROM) (maximum difference, 10°). Preoperatively, all knees were evaluated using the Knee Society Score (KSS) [20].

Inclusion criteria for both groups were the identical. Patients were eligible if they had an asymptomatic patellofemoral joint, no clear clinical evidence of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) instability and a body mass index (BMI) <35. Patients were included if they had a varus deformity <10°, a preoperative range of flexion of at least 110° and a flexion deformity <5°. Eligible patients had arthritic disease that did not exceed grade 4 in the medial compartment and grade 3 in the patellofemoral compartment according to the Älback classification [19].

The unicompartmental implant used in both groups was UC Sigma DePuy (Warsaw, IN, USA) with a flat, fixed, metal-backed tibial component. An anteromedial parapatellar approach using a 12-cm incision was used in all cases. All implants were cemented using the same technique. Postoperatively, all patients underwent the same standardised rehabilitation protocol, with full weight bearing as soon as tolerated. All UKAs in both groups were performed by two surgeons experienced in both navigation and UKA surgery (NC and AM).

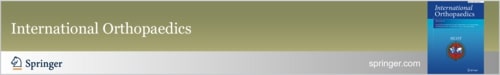

At latest follow-up, the clinical outcome was evaluated using both the KSS and Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) index [21]. The minimum follow-up for both groups was six months. All radiographs were performed using a standardised protocol to ensure correct magnification and rotation. Radiographs were repeated if any malrotation was detected. We painstakingly educated and communicated with our radiographers in order to obtain consistent films before embarking on this trial. Standing radiographs were obtained with the knee in maximum extension, the patella pointing forward and both hips and ankles visible on the film. Lateral radiographs were taken with the knee in 30° of flexion on a radiographic film 20 × 40 cm. An independent radiologist blinded to the implantation technique used assessed the radiographs. The mechanical axis of the limb [hip-knee-ankle angle (HKA)] was measured with a dedicated software application (IMPAX, Agfa-Gevaert, NV, USA) and used as the primary outcome measure. The frontal femoral component angle (FFC), the frontal tibial component angle (FTC) and the sagittal orientation (slope) of both femoral and tibial components were also determined. The FFC was determined as the angle between the mechanical axis of the femur and the transverse axis of the femoral component. The FTC was determined as the angle between the mechanical axis of the tibia and the transverse axis of the tibial component. The slope of the femoral component was evaluated by measuring the angle formed between a line drawn perpendicular to the two-peg tangentials and the anterior femoral cortex, whereas the tibial slope was evaluated by measuring the angle formed between a line drawn tangential to the baseplate (surface in contact with bone) of the respective components or posterior tibial cortex (Fig. 1). The ideal alignment in both groups was determined as a neutral mechanical axis with an HKA angle of 180°, FFC and FTC angles both of 90° and femoral and tibial slopes of 90° and 85°, respectively. Two independent orthopaedic surgeons not involved in the original surgery evaluated all patients.

Fig. 1.

Nominal femoral and tibial slopes, along with acceptance range

Statistical analysis of results was performed with a (nonparametric) Wilcoxon/Mann–Whitney test using Statistica software (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, AZ, USA), with significantly different threshold set at p ≤ 0.05.

Computer-assisted technique

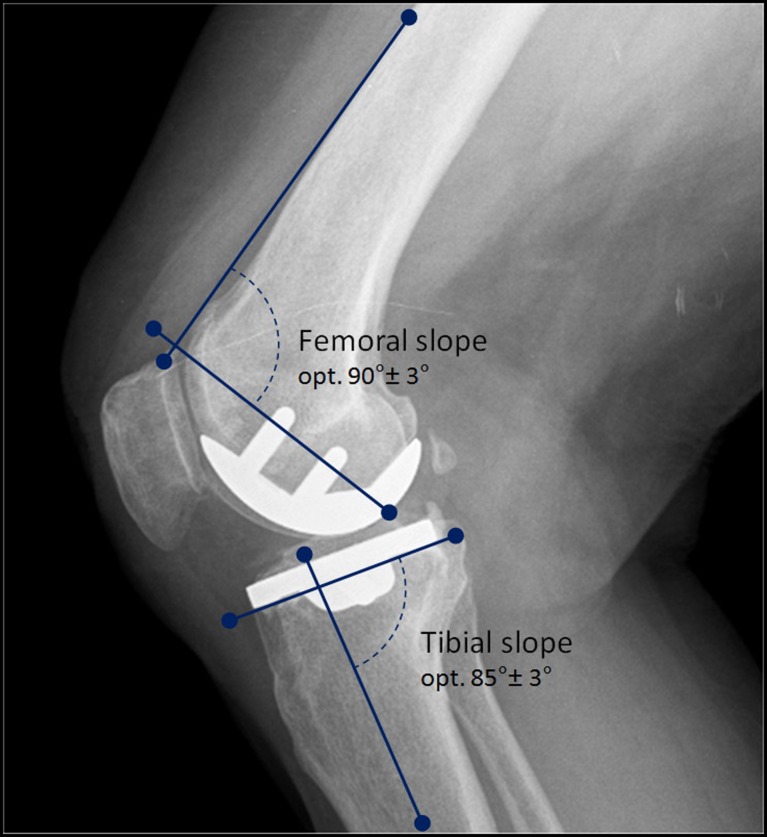

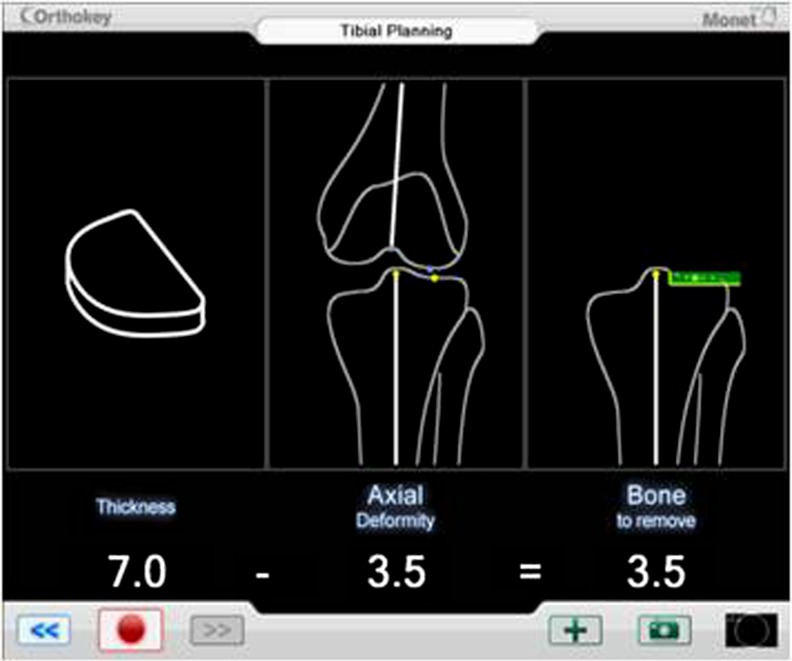

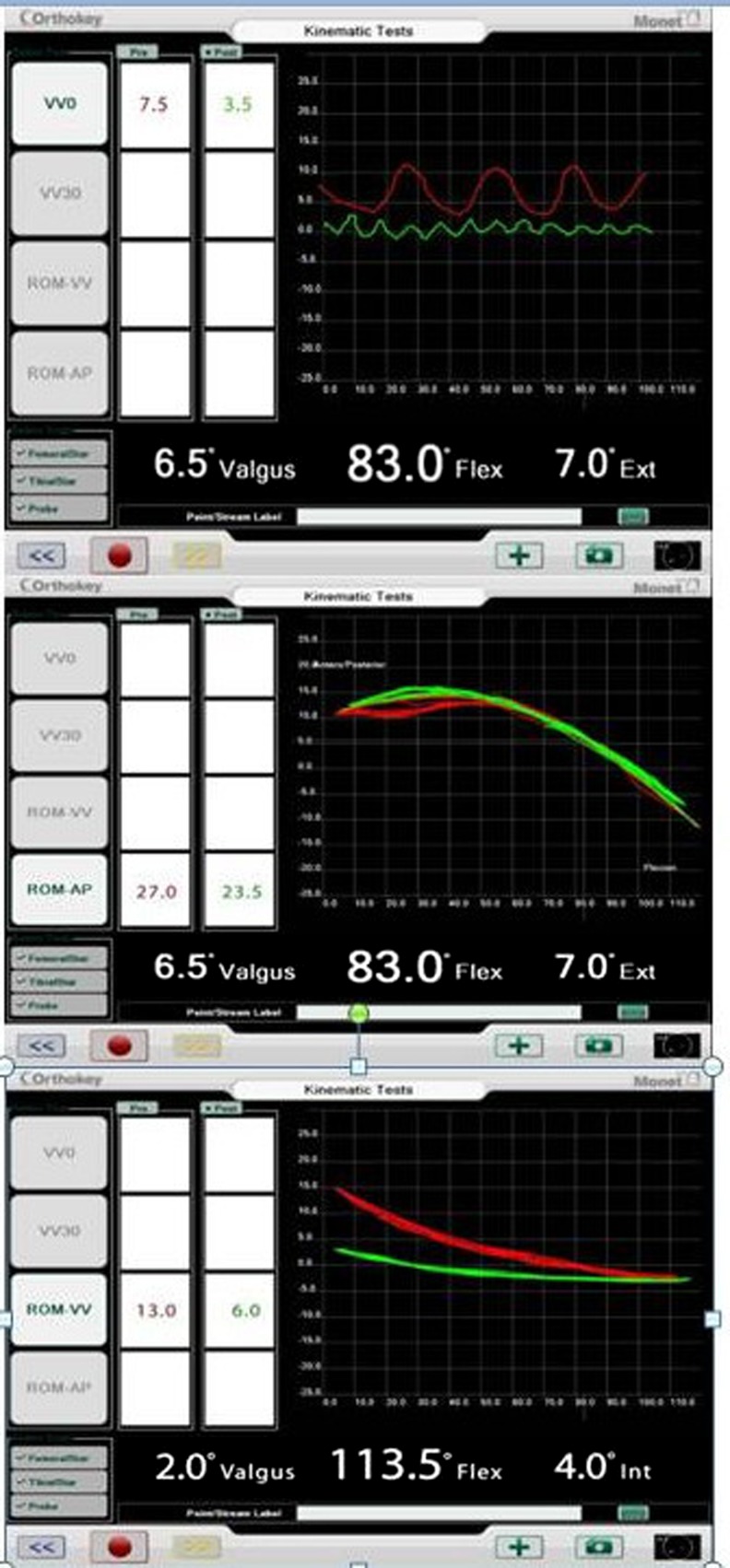

In group A, an imageless optical navigation system with dedicated software was used for UKA navigation (Monet, Orthokey, Florence, Italy). The navigation kit included two bony references for the tibia and femur and a special pointer designed for the registration phase and execution and control of bone cuts. Two 3-mm-diameter bicortical pins ensured stability and reduced morbidity. The navigated surgical tools were designed to integrate seamlessly with the conventional surgical set and reduce production and sterilisation costs as well as the number of disposables used in each surgery. Implant planning is based on the desired level of correction starting from the pathological state and taking into account bone-tissue sparing (Fig. 2). The slope can be compared with pre-operative image-based planning (Fig. 3), and the software provides the opportunity to evaluate knee kinematics during different surgical steps (Fig. 4) of the navigation process, which are based on the patient’s anatomy registration and preoperative assessment of limb alignment.

Fig. 2.

Navigated intraoperative planning showing the desired level of correction, taking into account bone-tissue sparing starting from the pathological grade

Fig. 3.

Navigated intraoperative assessment of the intraoperative “natural” slope

Fig. 4.

Navigated kinematic pre- and postassessment measurements of varus–valgus stability, femoral translation during flexion and varus–valgus deformity during flexion

The software is able to establish the minimal tibial bone resection to restore final limb alignment based on the recorded deformity. Tibial navigation and verification provides the height and slope of the bone cut, whereas planning for distal and posterior femoral shims is reduced to one single screen, allowing the ability to control limb alignment during femoral resection. Final limb alignment can be assessed with both trial and final implants.

Results

Demographic and pre-operative data are shown in Table 1. There were 18 women and 13 men in each group. Mean preoperative age was 70.9 (range 56–85) years for group A and 71.3 (range 58–83) years for group B. Mean pre-operative flexion was 118.4° (range 110°–130°) and 117.5° (range 110°–135°) for groups A and B, respectively. Mean pre-operative HKA angle was 173.8° (range 170°–179°) and 174.1° (range 171°–179°) for groups A and B, respectively. Pre-operatively, mean KSS was 44.5 (range 39–50) in group A and 43.7 (range 38–51) in group B. Pre-operative functional score was 48.4 (range 45–55) in group A and 47.6 (range 45–55) in group B. There were no statistically significant differences in pre-operative data between groups. Length of hospital stay was a mean of 5.5 (range four to nine) days in group A and 5.9 (range four to nine) days in group B. Difference in duration of patient hospital stay was not statistically significant. In the conventional UKA group, mean surgical time was statistically shorter at 35.4 min (range 26–45) compared with 47.4 min (range 43–62) in the navigated group.

Table 1.

Patient demographic data reported as mean (M), standard deviation (SD) and range (R)

| Group A, bi-UKA (18 F; 13 M) | Group B, TKA (18 F; 13 M) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | M 70.9 | M 71.3 |

| SD 7.8 | SD 6.8 | |

| R 56–85 | R 58–83 | |

| Preoperative flexion (degrees) | M 118.4° | M 117.5° |

| SD 6.2 | SD 6.3 | |

| R 110–130° | R 110–135° | |

| Preoperative HKA angle (degrees) | M 173.8° | M 174.1° |

| SD 2 | SD 2.1 | |

| R 170–179 | R 171–179° | |

| Preoperative IKS score | M 44.5 | M 43.7 |

| SD 3.4 | SD 3.1 | |

| R 39–50 | R 38–51 | |

| Preoperative functional score | M 48.4 | M 47.6 |

| SD 3.33 | SD 2.54 | |

| R 44–55 | R 45–55 |

HKA hip-knee-ankle, IKS International Knee Society, UKA unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, TKA total knee replacement

Postoperative KSS, functional scores, WOMAC indices and radiological parameters are presented in Table 2. At the latest follow-up, no statistically significant differences were found in the KSS and function scores between groups. The WOMAC Arthritis Index showed there was no statistical difference between groups for pain, function and stiffness. At the latest follow-up, no implant had been revised, and no intra-operative or postoperative complications related to implant selection was seen.

Table 2.

Postoperative results for the 31 patients in each study group. Data are reported as mean (M), standard deviation (SD) and range (R)

| Group A, bi-UKA (18 F; 13 M) | Group B, TKA (18 F; 13 M) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical time (minutes) | M 47.4 | M 36.4 | <0.0001 |

| SD 6.1 | SD 4.4 | ||

| R 43-62 | R 26-45 | ||

| Hospital stay (days) | M 5.5 | M 5.9 | 0.23 |

| SD 1.3 | SD 1.6 | ||

| R 4-9 | R 4-9 | ||

| HKA angle | M 178.4° | M 177.1° | <0.0006 |

| SD 1.1 | SD 1.7 | ||

| R 176–180° | R 175–182° | ||

| FFC angle | M 88.7° | M 89.2° | 0.21 |

| SD 1.5 | SD 1.3 | ||

| R 86–91 | R 86–91° | ||

| FTC angle | M 88.7° | M 87.1° | <0.0001 |

| SD 1.1 | SD 1.6 | ||

| R 87–90° | R 84–91° | ||

| Femoral slope | M 90.1° | M 89.7° | 0.41 |

| SD 1.6 | SD 1.7 | ||

| R 87–93° | R 86–94° | ||

| Tibial slope | M 86.1° | M 87.4° | 0.008 |

| SD 1.9 | SD 1.8 | ||

| R 83–90° | R 84–91° | ||

| IKS score | M 79.9 | M 79 | 0.51 |

| SD 5.1 | SD 4.6 | ||

| R 74-88 | R 73-88 | ||

| Functional score | M 83.7 | M 82.9 | 0.67 |

| SD 8 | SD 9.1 | ||

| R 70-100 | R 69-95 | ||

| WOMAC pain | M 4.9 | M 4.1 | 0.71 |

| SD 1.7 | SD 1.7 | ||

| R 1-7 | R 1-7 | ||

| WOMAC function | M 8.8 | M 9.2 | 0.46 |

| SD 1.5 | SD 2.2 | ||

| R 6-12 | R 6-13 | ||

| WOMAC stiffness | M 1.9 | M 2.2 | 0.12 |

| SD 0.9 | SD 0.7 | ||

| R 0-4 | R 1-4 |

HKA hip-knee-ankle, FFC frontal femoral component, FTC frontal tibial component, IKS International Knee Society, UKA unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, TKA total knee replacement, WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index

Nonparametric statistical analysis was performed using a Wilcoxon/Mann–Whitney test

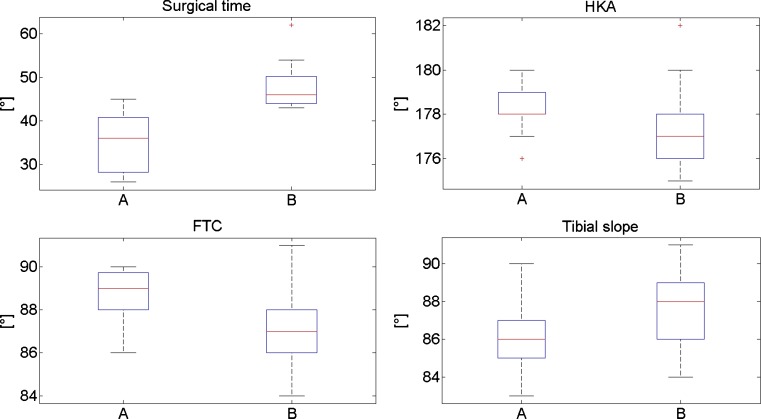

Radiological assessment at latest follow-up showed no statistically significant difference in FFC angle and femoral slope. The FTC angle was statistically better aligned (p < 0.0001) in the navigated group, with five cases of outliers (tibial component with an alignment <3° compared with the ideal alignment of 90°) in the conventional group. A significantly better tibial slope (p < 0.0008) was seen in the navigated group. The final HKA angle was statistically better aligned in the navigated group (p < 0.0006), with two cases of overcorrection from varus to valgus in the conventional group (respectively, 181° and 182°) (Fig. 5). No major signs of radiological loosening were seen in either group.

Fig. 5.

Distributions of surgical time, hip-knee-ankle angle (HKA), frontal tibial component angle (FTC) and tibial slope across the two patient groups, displayed in terms of median and quartile values. Crosses indicate outlier values; p values were <0.0001, <0.0006, <0.001 and <0.008, respectively

Discussion

UKA represents a valuable surgical option for the treatment of isolated tibiofemoral-compartment arthritis [22, 23]. Several authors document UKA survivorship similar to that for current TKA at less than ten year follow-up. Despite the potential advantages of UKA, several authors show that a substantial proportion of patients suitable for this type of prosthesis undergo knee arthroplasty [24–26]. As a result, the use of UKA has not been increasing despite a functionally superior outcome and reduced costs to health services [27]. Prime et al. report an unchanged incidence of ∼8 % for UKA among all primary knee replacements in the National British and Welsh Joint Registry over the last six years [28].

Several explanations are suggested to account for the reluctance of surgeons to use unicompartmental prostheses. Markel et al., in 2005, and Mercier et al., in 2010, pointed out that implantation of a UKA compared with TKA was more demanding and less forgiving [29, 30]. The technically challenging nature of UKA surgery and difficulties in achieving accurate implant placement may lead to a preference for TKA. There is no general agreement on the ideal UKA implant alignment, and positioning often depends only on the surgeon’s experience and skill level. Even intramedullary guiding systems do not offer optimal reproducible implantation techniques for UKA [29, 30]. During UKA implantation, special attention must be paid to avoiding overcorrection, which results in a valgus deformity and may lead to rapid progression of osteoarthritis in the lateral compartment [3, 4]. In addition, undercorrection <10° in a varus knee should be avoided because of a higher rate of polyethylene wear. Therefore, improved alignment after UKA is associated with better function and longevity [3, 4]. In 2001, Robertsson et al. pointed out that many cases of UKA failure might be related to surgeon inexperience, with better results being reported in high-volume centres [31].

Computer-assisted surgical navigation has the potential to improve the accuracy of implant positioning; however, its effect on clinical outcome is still not conclusive. The short- to mid-term results for computer-navigated versus conventional alignment techniques in TKA and UKA show no statistically significant clinical differences [13, 15, 17]. However, a limitation of the original UKA studies was the use of a software application intended for TKA navigation. Subsequently, Perlick et al., in 2004, reported that in navigated UKA, the danger of overcorrection is diminished by real-time information about the leg axis at each step during the operation [16].

In 2013, Weber et al., in a meta-analysis, compared 258 UKA prostheses implanted using a navigated technique and 295 using a conventional one in ten eligible studies [17]. Radiological alignment of both femoral and tibial components, limb mechanical axis and surgical time were assessed. The authors showed that despite a significantly longer surgical time, navigation permits a more precise component alignment but without proven clinical advantages. Valenzuela et al., in a recent study, reported a possible discrepancy between lower-limb mechanical axes assessed intra-operatively using the navigation and the final radiological assessment on weight bearing [18]. However, an almost identical implant posterior slope was seen in the navigated and weight-bearing radiological assessment. The authors reported a trend towards a more accurate restoration of limb alignment and implant positioning in the computer-assisted group and recommended the use of navigation in UKA, particularly for less experienced surgeons.

In our study, we matched two groups of patients who had undergone UKA using either specifically designed UKA navigation software or a conventional alignment technique. Clinical outcomes at short-term follow-up were compared using the KSS and WOMAC index. No advantage in clinical outcome was seen in the navigation group. In addition, UKA implantation using computer navigation resulted in a significant increase in surgical time and, as a result, in higher healthcare costs. Length of hospital stay was similar for both study groups, and no complications directly related to the navigation process were seen.

Our study also assessed the accuracy of implant positioning for the two alignment techniques. At final radiological assessment, a significantly better alignment of the lower-limb mechanical axis (HKA angle) was seen in the computer-navigated UKA group. In addition, a statistically significant improvement in the coronal (FTC angle) and sagittal alignment (slope) of the tibial component was seen in the navigated group. No incidence of overcorrection of mechanical axes from varus to valgus was seen with navigated UKA alignment but did occur in two cases using the conventional technique. There was no significant difference in coronal femoral alignment between groups. However, this axis was determined by the proximal femoral cut in both groups rather than directly using the navigation software.

Despite all surgeries in this study being performed by the same two experienced surgeons in an orthopaedic department performing a large number of UKA, the use of the specifically designed navigation software helped during all phases of the surgery. The navigation system provided the surgeons with instantaneous intra-operative feedback about implant placement. As such, this navigated alignment technique was deemed particularly useful in teaching hospitals and in low-volume centres.

Limitations of this study are a lack of blinding of individuals assessing clinical outcomes, and also that it was a retrospective analysis. In addition, measuring the effect of intra-observer or interobserver errors in the radiological assessment was not undertaken. However, a strength of this matched-paired study is the strict criteria used for patient selection and matching, which resulted in two homogeneous patient groups. Inclusion criteria included arthritis grade, patient age and gender and preoperative ROM.

In conclusion, accurate alignment of UKA components is technically demanding, and improvements have been shown with the use of computer navigation and dedicated software. The authors believe that computer navigation with dedicated software is capable of increasing the accuracy of implant alignment and should be considered to increase the reproducibility of the UKA surgical technique.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of interest

Alfonso Manzotti, Chris Pullen and Pietro Cerveri have no conflict of interest. Norberto Confalonieri has a financial relationship with DePuy (Warsaw, IN, USA) to develop the Monet software for UKA navigation.

References

- 1.John J, Kuiper JH, May PC. Age at follow-up and mechanical axis are good predictors of function after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. An analysis of patients over 17 years follow-up. Acta Orthop Belg. 2009;75(1):45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kennedy WR, White RP. Unicompartmental arthroplasty of the knee. Postoperative alignment and its influence on overall results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;221:278–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ridgeway SR, McAuley JP, Ammeen DJ, Engh GA. The effect of alignment of the knee on the outcome of unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:351–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.84B3.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarangi PP, Karachalios T, Jackson M, Newman JH. Patterns of failed internal unicompartmental knee prostheses, allowing persistence of undercorrection. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1994;80:217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Voss F, Sheinkop MB, Galante JO, Barden RM, Rosenberg AG. Miller-Galante unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at 2- to 5-year follow-up evaluations. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:764–71. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(05)80072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernigou P, Deschamps G. Alignment influences wear in the knee after medial unicompartmental arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;423:161–5. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000128285.90459.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernigou P, Deschamps G. Posterior slope of the tibial implant and the outcome of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:506–11. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200403000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kort NP, van Raay JJ, Thomassen BJ. Alignment of the femoral component in a mobile-bearing unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a study in 10 cadaver femora. Knee. 2007;14:280–3. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bae DK, Song SJ. Computer assisted navigation in knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg. 2011;3:259–67. doi: 10.4055/cios.2011.3.4.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zamora LA, Humphreys KJ, Watt AM, Forel D, Cameron AL. Systematic review of computer-navigated total knee arthroplasty. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:22–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakano N, Matsumoto T, Ishida K, Tsumura N, Kuroda R, Kurosaka M. Long-term subjective outcomes of computer-assisted total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;37:1911–5. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-1978-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaffe M, Chan P, Goyal N, Luo M, Cayo M, Stulberg SD. Computer-assisted versus manual TKA: no difference in clinical or functional outcomes at 5-year follow-up. Orthopedics. 2013;36:e627–32. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20130426-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenny JY, Boeri C. Accuracy of implantation of a unicompartmental total knee arthroplasty with 2 different instrumentations: a case-controlled comparative study. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:1016–20. doi: 10.1054/arth.2002.34524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Keene G, Simpson D, Kalairajah Y. Limb alignment in computer-assisted minimally-invasive unicompartmental knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:44–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B1.16266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim MH, Tallay A, Bartlett J. Comparative study of the use of computer assisted navigation system for axial correction in medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17:341–6. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0655-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perlick L, Bathis H, Tingart M, et al. (2004) Minimally invasive unicompartmental knee replacement with a nonimage-based navigation system 28:193–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Weber P, Crispin A, Schmidutz F, Utzschneider S, Pietschmann MF, Jansson V, Müller PE (2013) Improved accuracy in computer-assisted unicondylar knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Valenzuela GA, Jacobson NA, Geist DJ, Valenzuela RG, Teitge RA. Implant and limb alignment outcomes for conventional and navigated unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:463–8. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahlbäck S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1968;277:7–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, Scott WN. Rationale of the Knee Society Clinical Rating System. Clin Orthop. 1998;248:13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manzotti A, Confalonieri N, Pullen C. Unicompartmental versus computer-assisted total knee replacement for medial compartment knee arthritis: a matched paired study. Int Orthop. 2007;31:315–9. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Confalonieri N, Manzotti A, Pullen C. Navigated shorter incision or smaller implant in knee arthritis? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;463:63–7. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31811f3a30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berger RA, Meneghini RM, Jacobs JJ, Skeinkop MB, Della Valle CJ, Rosenberg AG, Galante JO. Results of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty at a follow-up of ten-years follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87A:999–1006. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.00568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman JH, Ackroyd CE, Shah NA. Unicompartmental or total knee replacement ? J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;80B:862–865. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.80b5.8835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman J, Pydisetty RV, Ackroyd C. Unicompartmental or total knee replacement: the 15-year results of a prospective randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:52–7. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B1.20899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willis-Owen CA, Brust K, Alsop H, Miraldo M, Cobb JP. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty in the UK National Health Service: an analysis of candidacy, outcome and cost efficacy. Knee. 2009;16:473–8. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prime MS, Palmer J, Khan WS (2011) The National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Orthopedics [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Mercier N, Wimsey S, Saragaglia D. Long-term clinical results of the Oxford medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2010;34:1137–43. doi: 10.1007/s00264-009-0869-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Markel DC, Sutton K. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: trouble shooting implant positioning and technical failures. J Knee Surg. 2005;18:96–101. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, Lidgren L. The routine of surgical management reduces failure after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:45–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B1.10871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]