Abstract

Purpose

A study was conducted to compare minimum 15-year survivorship and outcome of the Genesis I and II implants for total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed 245 consecutive TKA implanted between January 1995 and October 1997. Genesis I was implanted in 156 knees and Genesis II in 89 knees.

Results

At 15–17 years, 75 patients (31 %) had died, 28 patients (11 %) were lost to follow-up and 11 TKA were revised (4.6 %), including ten Genesis I (6.4 %) and one Genesis II (1.1 %); 131 TKA (53 %) were available for follow-up. Cumulative survivorship was 92.4 % at 15.7 years. Survival in patients <69 years at surgery was lower (88.0 %) compared with patients ≥69 years (98.5 %; p = 0.023). In patients <69 years, Genesis I survival (84.3 %) was worse compared with Genesis II (97.1 %) (p = 0.018). Polyethylene (PE) Insert thickness ≤11 mm had significantly better survivorship (97.1 %) compared with PE >11 mm (56.7 %) (p < 0.0001)

Conclusions

At a minimum of 15 years, the overall (92.4 %) survivorship of Genesis TKA was good, with excellent (98.1 %) survivorship of the Genesis II design. Revision rates were higher with Genesis I in the younger age group and with insert thickness >11 mm, possibly due to longer shelf life of less frequently used sizes.

Keywords: Total knee arthroplasty, Long-term outcome, Implant design, Polyethylene thickness

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is a common orthopaedic procedure performed with increasing frequency [1]. Outcome is described as the function of several variables, including survival [2], kinematics [3], function [4] and patient satisfaction [5]. None of these approaches covers the full spectrum of reality. Historic papers reporting long-term results are still used as benchmarks in the orthopaedic literature [6, 7] but often deal with obsolete implants and outdated patient selection criteria, large dropout numbers and changes in patient function and activity over 15–20 years. The current patient profile for TKA in terms of age and disease progression is quite different from historic publications [8]. In the United States, the demand for primary TKA among patients <65 years is predicted to exceed 50 % of TKA patients by 2016 [8]. For arthritic patients with 20–40 years remaining life expectancy, reliable long-term follow-up data on TKA are a sound basis for decision making. Therefore, studies on longer-term follow-up after TKA performed in the past decade [7, 9–18] deserve further attention, despite the logistic problems and limitations. Besides, reliable long-term data on implants still in use can serve to evaluate quality and performance of new devices.

In this study, we analysed two different TKA designs: Genesis I and Genesis II (Smith & Nephew, Memphis, TN, USA) at 15–17 years follow-up. Genesis I is no longer commonly implanted, whereas Genesis II is still widely used. Despite the similarity in name, the two implants have different geometry. Genesis I was one of the first modular implants with a built-up module to convert the device from a cruciate-retaining (CR) to a posterior stabilised (PS) design by resecting an additional extra 4 mm from the distal femur on top of the regular 9-mm resection. The polyethylene (PE) post was tall, and accommodation of the femoral box required significant bone removal. In comparison, the Genesis II implant has a nonmodular, distinct CR and PS component, with a more rounded and less prominent post. Also, tibial coverage and the trochlear groove on the femoral component are more anatomic. Hence our research questions were: (1) What is the survivorship and clinical outcome of a consecutive series of TKA at 15–17 years of follow-up? (2) Is there a difference in outcome between the two TKA designs? (3) Can determinant implant and patient factors be established?

Patients and methods

Between January 1995 and October 1997, 245 consecutive primary TKA were performed on 220 patients by a single surgeon (JV). Cohort 1 consisted of 156 Genesis I knees and cohort 2 of 89 Genesis II knees. Patients were operated through a standard anteromedial approach. The patella was everted and resurfaced in all cases. Femoral alignment was guided by an intramedullary rod and tibial alignment by an extramedullary rod. Knees were implanted with a measured resection technique and standard instrumentation. The choice for a CR or PS implant was made after assessment of deformity and ligament status. All tibial and patellar components were cemented. Femoral fixation included both uncemented and cemented cases.

Clinical and radiographic data were documented in a prospective database. Pre-operative and six week postoperative imaging included full-leg, standing X-rays and standing anteroposterior (AP), lateral and skyline views. At 15–17 years of follow-up, patients were examined by an independent study nurse. Range of motion (ROM), stability and swelling were noted. Knee Society Score (KSS) [19] and Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) [20] were computed. Radiolucent lines were documented on AP and lateral views, according to the Knee Society scoring system [21]. Alignment was measured on full-leg views, represented as the hip-knee-ankle (HKA) angle (angle formed between the tibial and femoral mechanical axes in the coronal plane). PE thickness was measured on AP views of the medial and lateral compartment (Fig. 1). The estimated amount of linear wear was calculated by deducting the measured thickness, corrected for magnification, from the initial PE thickness, as disclosed by the manufacturer.

Fig. 1.

Polyethylene (PE) thickness of medial and lateral compartments measured on anteroposterior radiographs. The estimated amount of linear wear was calculated by deducting the measured thickness, corrected for magnification, from the initial PE thickness, as disclosed by the manufacturer

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS Statistics 21 (SPSS, an IBM Company, Chicago, IL, USA). Level of statistical significance was 0.05. Research questions were examined as follows: (1) Kaplan-Meier survivorship analysis was performed for the total cohort; clinical and radiographic outcome were analysed for the nonrevised knees available at the 15- to 17-year follow-up. (2) Comparison of survival of the two TKA designs was performed using the log rank (Mantel-Cox) test. (3) In order to establish determinant patient and implant factors, subanalysis was performed by gender, age at surgery, body mass index (BMI), femoral fixation mode and PE insert thickness using parametric or nonparametric tests, as appropriate. Log-rank test was used to establish the difference in implant survivorship between subgroups.

Results

Pre-operative demographic distribution of the two cohorts was comparable in terms of gender, BMI, clinical scores, varus/valgus distribution and amount of pre-operative coronal deformity (p > 0.1) (Table 1). Mean age at surgery was significantly lower in the Genesis II cohort (p = 0.016). Distribution of femoral component fixation mode and PE insert thickness was similar.

Table 1.

Demographics of the study cohort and group comparison

| Genesis I | Genesis II | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 156 | 89 | |

| Gender | M 26.9 %, F 73.1 % | M 25 %, F 75 % | 0.417 |

| Age at surgery |

Mean 69.3 years (SD 9.45) Median 69.4 years (27–89) |

Mean 66.0 years (SD 9.61) Median 67.9 years (27–84) |

0.016 |

| BMI |

Mean 28.5 (SD 4.77) Median 27.5 (18.7–42.3) |

Mean 28.4 (SD 5.03) Median 28.7 (17.5–42.5) |

0.811 |

| Femoral component |

Cemented 75 (48 %) Uncemented 81 (52 %) |

Cemented 42 (47 %) Uncemented 47 (53 %) |

0.894 |

| Insert size |

Median 10 mm 10 (83 %); 12 (15 %); 15 (2 %) |

Median 11 mm 9 (41 %); 11 (51 %); 13 (7 %); 15 (1 %) |

0.956 |

| Varus/valgus | 98/48 | 62/25 | 0.172 |

BMI body mass index, SD standard deviation

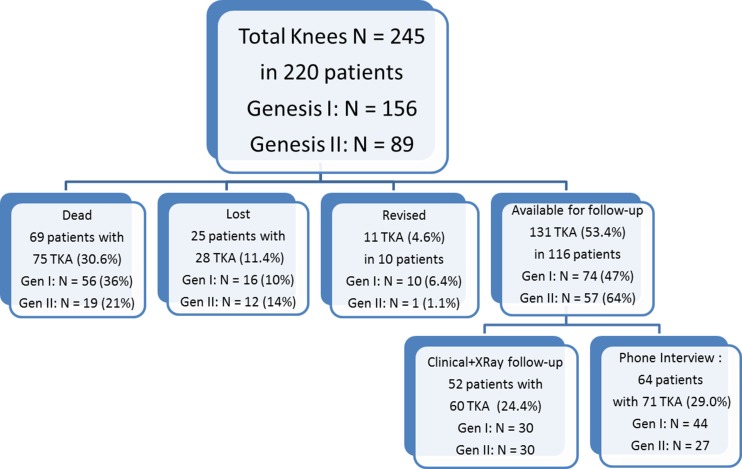

At 15–17 years, 69 patients with 75 TKA (30.6 %) had died, and 25 patients with 28 TKA (11.4 %) were lost to follow-up (Fig. 2). Overall, mean follow-up was 11.0 (0.5–16) years. In all but two lost patients, files indicated an uneventful course at last follow-up. One patient (Genesis I, PS), lost at 11 years, complained of mild pain. He had undergone TKA after a complex tibial fracture. The tibial component displayed 4° varus without radiolucent lines. The other symptomatic patient (Genesis II, PS) was lost after three years, with mild complaints related to the extensor mechanism. Patellar tracking and fixation was fine. All patients in the lost cohort would presently be at least 80 years old (mean age 87, range 80–105), hence, most are probably deceased. Eleven TKA (in ten patients) were revised, including ten Genesis I for infection (1), recurrent dislocation (1), femoral component loosening (1), patella loosening (2) or PE wear (5), and one Genesis II for PE wear (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

All patients: dead, lost, revised and available for 15–17 years’ follow-up in the global population and in the Genesis I (Gen I) and Genesis II (Gen II) cohorts

Table 2.

Details of revised cases of Generation (Gen) I and II total knee arthroplasty (TKA)

| Patient | Age at surgery | BMI | TKA type | Constraint/ fixation | Insert size | PE sterilisation | Revised at | Failure mode | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 66 | 25 | Gen I | PS/C | 12 | Gamma | 1 year | Infection |

| 2 | F | 67 | 36 | Gen I | PS/C | 12 | Gamma | 1 year | Dislocation |

| 3 | F | 64 | 35 | Gen I | CR/UC | 10 | EtO | 9 years | Patella loosening |

| 4 | M | 63 | 27 | Gen I | PS/C | 15 | Gamma | 10 years | Patella loosening |

| 5 | F | 68 | 25 | Gen I | CR/UC | 12 | Gamma | 12 years | PE wear /instability |

| 6 | M | 64 | 27 | Gen I | PS/C | 15 | Gamma | 13 years | PE wear /infection |

| 7 | F | 71 | 41 | Gen I | CR/UC | 12 | EtO | 11 years | Femoral loosening |

| 8 | F | 60 | 32 | Gen I | PS/C | 10 | EtO | 15 years | PE wear |

| 9 | F | 62 | 37 | Gen I | PS/C | 12 | Gamma | 13 years | PE wear/loosening |

| 61 | Gen I | CR/UC | 12 | Gamma | 15 years | PE wear | |||

| 10 | F | 27 | 30 | Gen II | PS/C | 11 | EtO | 15 years | PE wear/Instability |

BMI body mass index, PS posterior stabilized, CR cruciate retaining, C cemented, UC uncemented, PE polyethylene, EtO ethylene oxide

The remaining 116 patients with 131 TKA (53.4 %) could be contacted for the 15- to 17-year follow-up. In 64 patients who were unfit to come to the clinic because of advanced age (mean 83 years) or disease, data were gathered via a telephone interview (71 TKA). Clinical and radiological examination was obtained in 52 patients (60 TKA) (Fig. 2).

Outcome at 15–17 years

KSS improved from 39 [standard deviation (SD 16.5)] to 81 (SD 9.2) in Genesis I and from 41 (SD 14.1) to 83 (SD 10.3) in Genesis II. Postoperative KOOS scores for symptoms, pain, daily activity and quality of life were similar in both groups (mean total KOOS Genesis I, 86 (SD 33), Genesis II 89 (SD 40); p > 0.1). Radiographs six weeks postoperatively revealed varus deformity (HKA > 3°) in 26 knees (range 4–5.5°) and valgus deformity (HKA < −3°) in 13 knees (range −3.5° to −5°). At 15–17 years postoperatively, 60 TKA (30 in each cohort) were analysed. Radiolucencies of 1 mm were noted in two cases on the tibial side and one case on the femoral side. No patellar radiolucencies were observed. In Genesis I, wear on the medial side averaged 0.76 mm (SD 0.53) versus 0.89 (SD 0.52) on the lateral side; in Genesis II, these values were 0.82 (SD 0.52) and 0.79 (SD 0.50), respectively. There was no difference between groups (p > 0.1) .

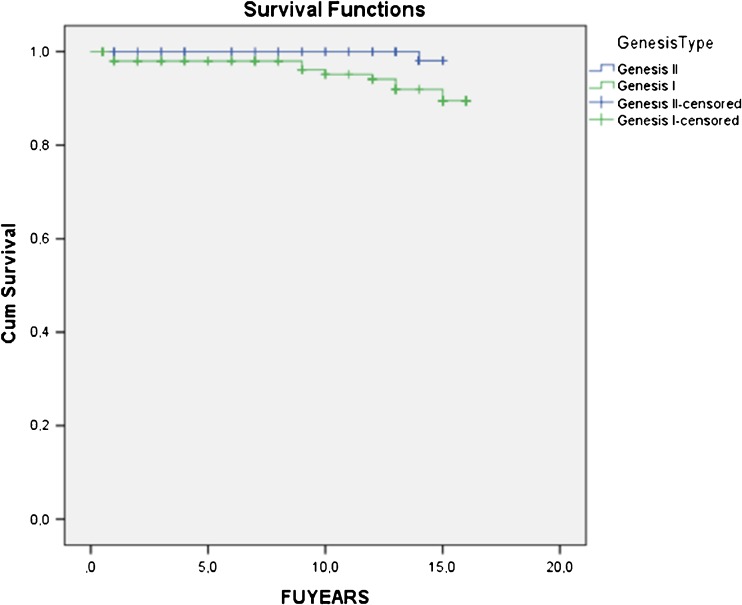

Survivorship

Overall Kaplan-Meier cumulative survivorship was 92.4 % at 15.7 years [95 % confidence interval (CI) 91.0–93.7]. Survivorship in the Genesis I group was 90.1 % at 15.5 years (95 % CI 88.0–92.2) and in Genesis II 98.1 % at 15.0 years (95 % CI 97.8–98.3) (Fig. 3). The difference was not statistically significant (Log rank 3.136; p = 0.077).

Fig. 3.

Survivorship in the Genesis I group was 90.1 % at 15.5 years [95 % confidence interval (CI) 88.0 – 92.2) and in the Genesis II group 98.1 % at 15.0 years (95 % CI 97.8 – 98.3). The difference was not statistically significant (Log rank 3.136; p = 0.077)

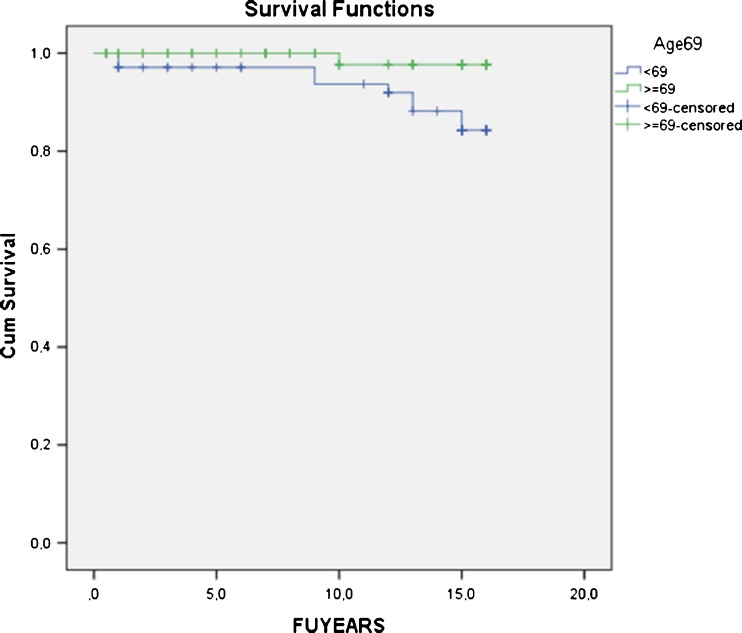

There was no difference in survivorship between genders (Log rank 0.184; p = 0.668) or femoral component fixation (Log rank 1.315; p = 0.251). No difference in postoperative coronal alignment between revised and nonrevised patients was observed ( p < 0.1); although revised patients had a mean BMI of 31.5 (25–41), there was no difference in survivorship between BMI <30 and ≥30 (Log rank 1.403; p = 0.236). TKA survival in patients <69 years (overall median age) at surgery was significantly worse (88.0 % at 15.4 years; 95 % CI 85.8–90.4) compared with patients of ≥69 years at surgery (98.5 % at 15.9 years; 95 % CI 97.4–99.6; Log rank 5.135; p = 0.023) (Fig. 4). In patients <69 years, survivorship of Genesis II was significantly better (97.1 %; 95 % CI 96.7–97.5) compared with 84.3 % (95 %; CI 80.5–88.1) for Genesis I (Log rank 5.598; p = 0.018). The odds ratio (OR) for revision of a Genesis I implant was 12.2 compared with a Genesis II.

Fig. 4.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) survival in patients <69 years (overall median age) at surgery was significantly worse [88.0 % at 15.4 years; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 85.8 – 90.4] compared with patients ≥69 years at surgery (98.5 % at 15.9 years; 95 % CI 97.4 – 99.6); p = 0.023

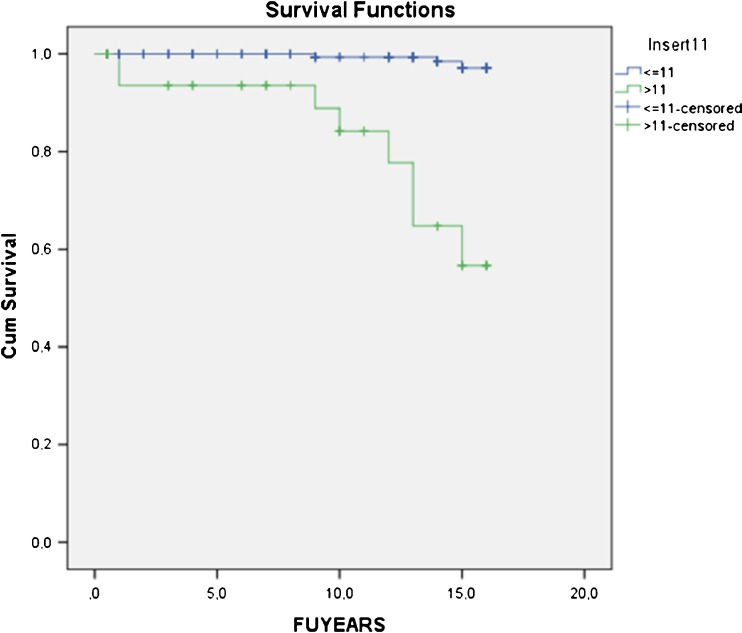

Analysis of different insert size groups revealed significantly worse implant survival with PE thickness >11 mm (56.7 % at 14.0 years; 95 % CI 49.5–62.9), which were less frequently used (13.9 % of inserts) compared with PE thickness ≤11 mm (97.1 % at 15.9 years; 95 % CI 96.5–97.7) (Log rank 45.657; p < 0.0001) (Fig. 5). The OR for revision of a PE insert >11 mm was 35.3.

Fig. 5.

Survival with polyethylene (PE) thickness >11 mm [56.7 % at 14.0 years; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 49.5–62.9] was significantly worse compared with PE thickness ≤11 mm (97.1 % at 15.9 yearsl; 95 % CI 96.5 –97.7); p < 0.0001

Discussion

This study describes the long-term outcome of a consecutive series of 245 TKA in 220 patients consisting of two cohorts of different Genesis implants. Overall, the 92.4 % survivorship at 15.7 years is good, with excellent 98.1 % survivorship of the Genesis II design. The main weakness of the study is the number of dropouts. At 15–17 years, 69 patients had died and 25 were lost to follow-up. Lost patients were >80 years at the time of evaluation; hence, it is logical to assume that many of them had died. In addition, only two of these patients were symptomatic at last follow-up. Advanced age in the majority of patients is a typical phenomenon of long-term joint replacement studies, reducing function scores as a discriminative parameter [17]. Callaghan et al. reported on 26 living patients remaining from an initial cohort of 86 patients. Despite the excellent KSS of 89, the function score dropped to 67. [17]

Minimum 15-year follow-up reports after TKA are not abundant, and several publications deal with implants no longer commonly used. Van Loon et al. followed 102 cemented Kinematic TKA (Howmedica, Rutherford, NJ, USA) at ten to 15 years after surgery and reported 62 % survival at 14 years, with deep infection and wear being the main reasons for revision [10]. Buechel reported 83 % survival of the meniscal-bearing PC-retaining LCS prosthesis (DePuy Warsaw, IN, USA) at 16 years [11]. Ito et al. examined a cohort of 36 Kinematic knees in 25 patients with rheumatoid arthritis and reported 93.7 % survival at 15 years [12]. Dixon et al. found 95.6 % survival at 15 years in 139 PC-retaining press-fit condylar (PFC) prostheses (DePuy), with PE wear as the leading cause for reoperation [13]. Less-favourable results of this implant (85 % survivorship at 15 years) were reported by Duffy et al. due to PE wear and osteolysis from ten years onwards [14]. Baker et al. confirmed these relatively high failure rates at 15-years’ follow-up in 501 primary PFC TKA. Survivorship for cemented implants was 80.7 % and for cementless implants 75.3 % [15]. Paratte et al. studied a cohort of different implants and assessed coronal alignment as a predictive parameter for implant survival. They reported overall survival of 86 % at 15 years [16].

In contrast to the latter findings, we were unable to detect a correlation between postoperative alignment or femoral component fixation and odds for failure. On the other hand, we found a significant difference in survivorship between thinner and thicker PE inserts. Insert sizes >11 mm had a low survival of 56.7 % at 14 years. As these sizes were used less frequently (13.9 % of total), their shelf life may have been longer. Especially in the Genesis I cohort, where gamma radiation in air was still in use as a sterilisation method, this may have caused PE degradation and increased wear, leading to implant failure [22].

Long-term comparative studies of different TKA implant designs are scarce. Kim et al. compared long-term follow-up between two different implants in 108 patients who <51 years at the time of surgery. The patients received an AMK fixed-bearing knee on one side and an LCS mobile-bearing TKA (both DePuy) on the other side. Survivorship at 16.8 year was 95 % for the fixed-bearing knees and 97 % for the mobile-bearing implants [18]. In our comparative study, the Genesis I is no longer commonly in use, but the implant in Genesis II is still widely used. Genesis II TKA with the more anatomic tibial coverage and trochlear design demonstrated superior survival rates compared with Genesis I, but the difference was only statistically significant in the younger age group (<69 at surgery). In the surviving TKA, there was no difference in clinical (KOOS) or radiographic outcome between cohorts. Several reports on the Genesis II implant are available but none with a 15-year follow-up [23–25]. Two prospective, randomized studies compared cruciate-retaining and substituting TKA with this implant and detected no significant difference in function between groups [23, 24]. Bourne et al. [25] reported 98 % survival at a mean of 9.5 (five to 11) years’ follow-up , supporting data obtained in our study. With regard to patient-related factors, in our study, implant survival was worse in women (91.6 % versus 94.8 % in men) and individuals with BMI ≥30 (83.5 % versus 93.5 % with BMI <30); those differences were not statistically significant. Only younger age (<69 years) at surgery significantly increased the revision risk. A recent report from the Finnish Arthroplasty Registry on 32019 TKA confirms the higher revision risk in patients <65 at surgery [26].

In conclusion, we reported good (92.4 %) survivorship in a group of 245 Genesis TKA at 15–17 years’ follow-up and superior (98.3 %) survival of the Genesis II design. Revision risk was significantly increased with younger age (<69 years) at surgery and with PE thickness >11 mm, possibly related to longer shelf life in less frequently used insert sizes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Stephanie Desutter for her help with data collection and input.

References

- 1.Kurtz SM, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780–785. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray DW, Carr AJ, Bulstrode C. Survival analysis of joint replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:697–704. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B5.8376423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dennis DA, Komistek RD, Scuderi GR, Zingde S. Factors affecting flexion after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:53–60. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e31812f785d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Witvrouw E, Victor J, Bellemans J, Rock B, Van Lummel R, Vanderslikke R, Verdonk R. A correlation study of objective functionality and WOMAC in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2002;10:347–351. doi: 10.1007/s00167-002-0302-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Font-Rodriguez DE, Scuderi GR, Insall JN. Survivorship of cemented total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;345:79–86. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199712000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodriguez JA, Bhende H, Ranawat CS. Total condylar knee replacement: a 20-year followup study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;388:10–17. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Ke Z, Kelly M, Bozic KJ. Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: national projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:2606–2612. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0834-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Argenson JN, Parratte S, Bertani A, Aubaniac JM, Lombardi AV, Berend KR, Adams JB, Lonner JH, Mahoney OM, Kinsey TL, John TK, Conditt MA. The new arthritic patient and arthroplasty treatment options. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(suppl 5):43–48. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Loon CJM, Wisse MA, de Waal Malefijt MC, Jansen RH, Veth RPH. The kinematic total knee arthroplasty. A 10- to 15-year follow-up and survival analysis. Acta Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buechel FF. Long-term follow-up after mobile-bearing total knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:40–50. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ito J, Koshino T, Okamoto R, Tomoyuki S. 15-Year follow-up study of total knee arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:984–992. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00262-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon MC, Brown RR, Parsch D, Scott RD. Modular fixed-bearing total knee arthroplasty with retention of the posterior cruciate ligament. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:598–603. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.00591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duffy GP, Crowder AR, Trousdale RR, Berry DJ. Cemented total knee arthroplasty using a modern prosthesis in young patients with osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baker PN, Khaw FM, Kirk LM, Esler CN, Gregg PJ. A randomized controlled trial of cemented versus cementless press-fit condylar total knee replacement: 15-year survival analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1608–1614. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.89B12.19363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paratte S, Pagnano MW, Trousdale RT, Berry DJ. Effect of postoperative mechanical axis alignment on the fifteen-year survival of modern, cemented total knee replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2143–2149. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaghan J, Wells C, Liu S, Goetz DD, Johnston RC. Cemented rotating platform total knee replacement: a concise follow-up, at at minimum of twenty years, of a previous report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1635–1639. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim YH, Kim JS, Choe JW, Kim HJ. Long-term comparison of fixed-bearing and mobile bearing total knee replacements in patients younger than fifty-one years of age with osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:866–873. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Insall JN, Dorr LD, Scott RD, et al. Rationale of the knee society clinical rating system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:13–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Groot IB, Favejee MM, Reijman M, Verhaar JA, Terwee CB. The Dutch version of the knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score: a validation study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:16–27. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-6-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ewald FC. The Knee Society total knee arthroplasty roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohl JR, Bohl WR, Postak PD, Greenwald AS. The Coventry Award. The effects of shelf life on clinical outcome for gamma sterilized polyethylene tibial components. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;367:28–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Victor J, Banks S, Bellemans J. Kinematics of posterior cruciate-retaining versus –substituting total knee arthroplasty. A prospective randomised outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:646–655. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B5.15602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harato K, Bourne RB, Victor J, Snyder M, Hart J, Ries MD. Midterm comparison of posterior cruciate-retaining versus –substituting total knee arthroplasty using the Genesis II prosthesis. A multicenter prospective randomized clinical trial. . Knee. 2008;15:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bourne RB, Laskin RS, Guerin JS. Ten-year results of the first 100 Genesis II total knee replacement procedures. Orthopedics. 2007;30(8 suppl):83–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Julin J, Jämsen E, Puolakka T, Konttinen YT, Moilanen T. Younger age increases the risk of early prosthesis failure following primary total knee replacement for osteoarthritis. A follow-up study of 32,019 total knee replacements in the Finnish Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2010;81(4):413–419. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2010.501747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]