Abstract

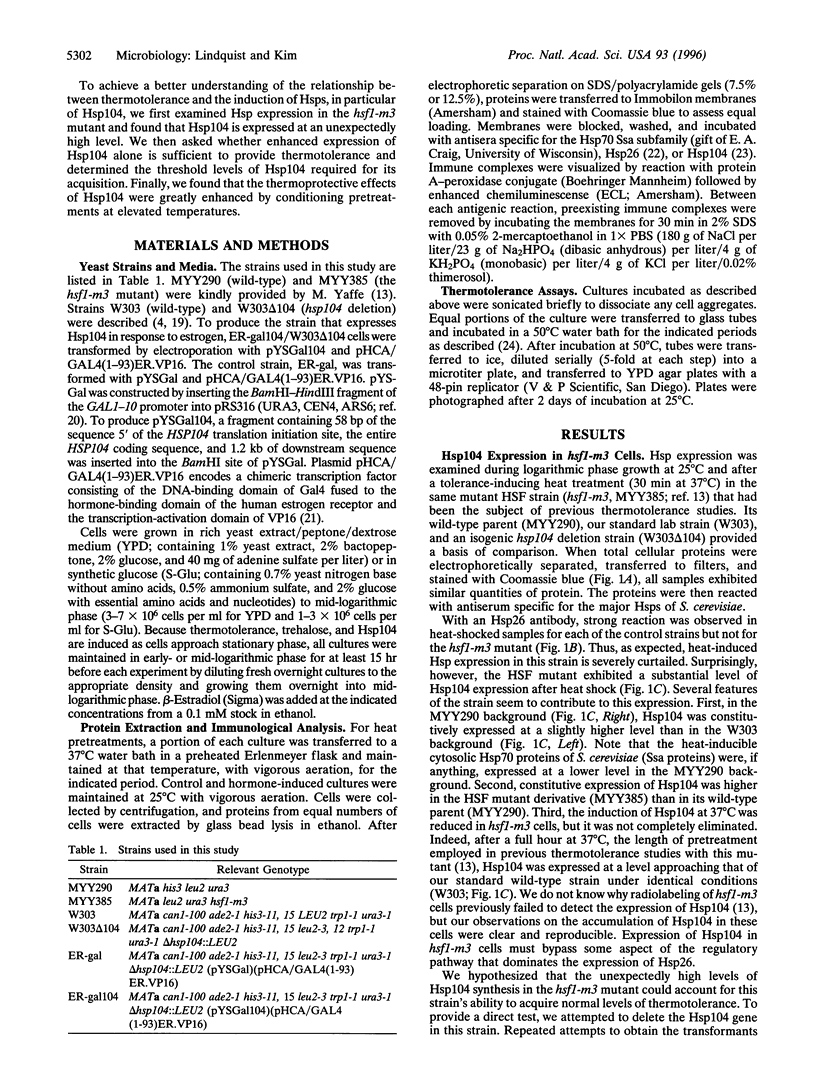

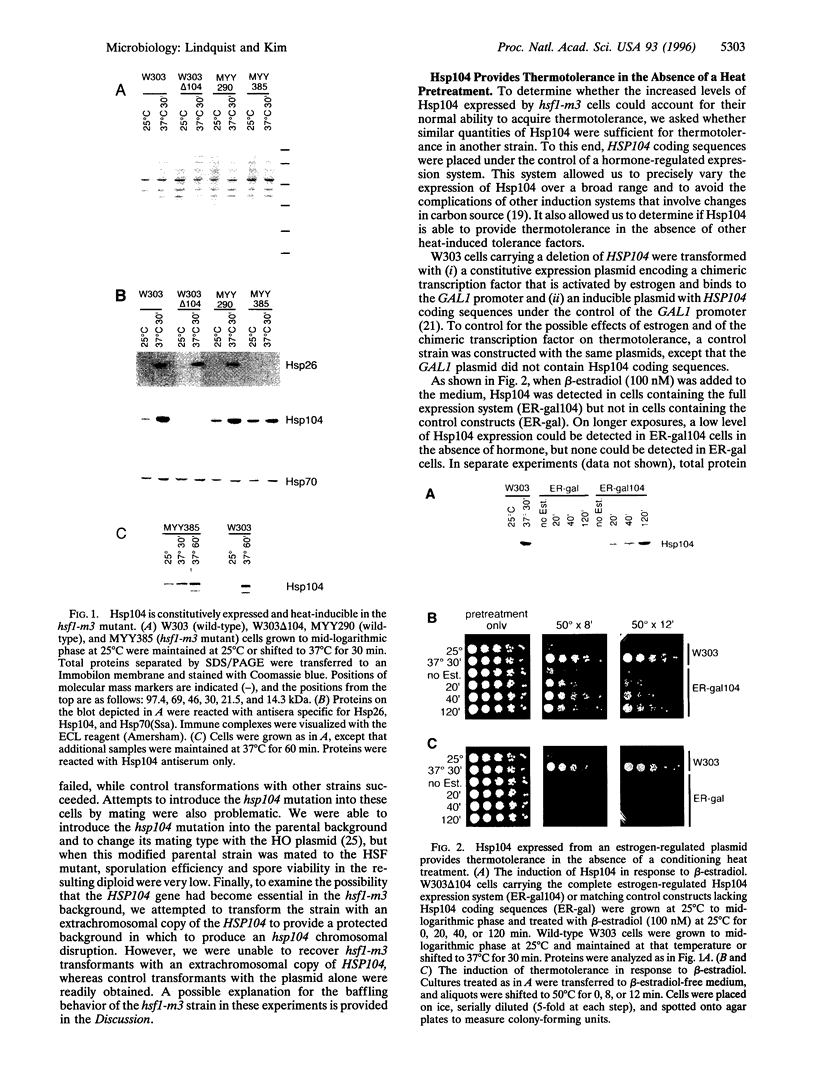

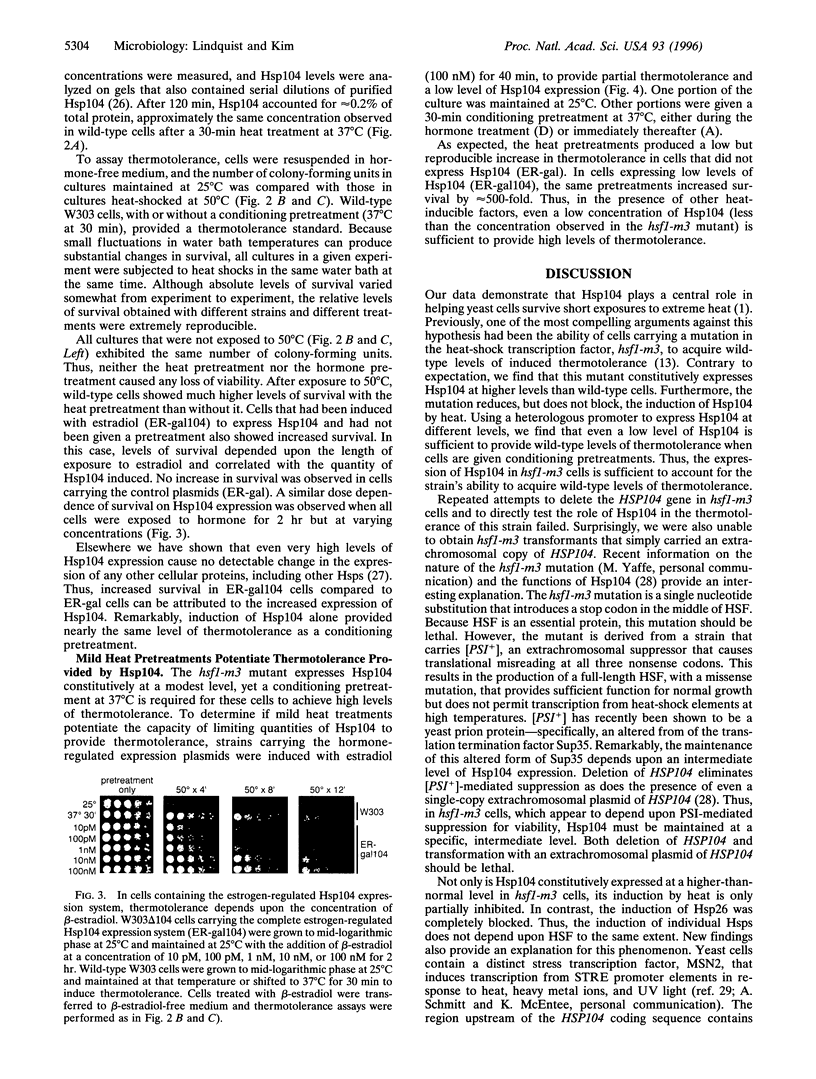

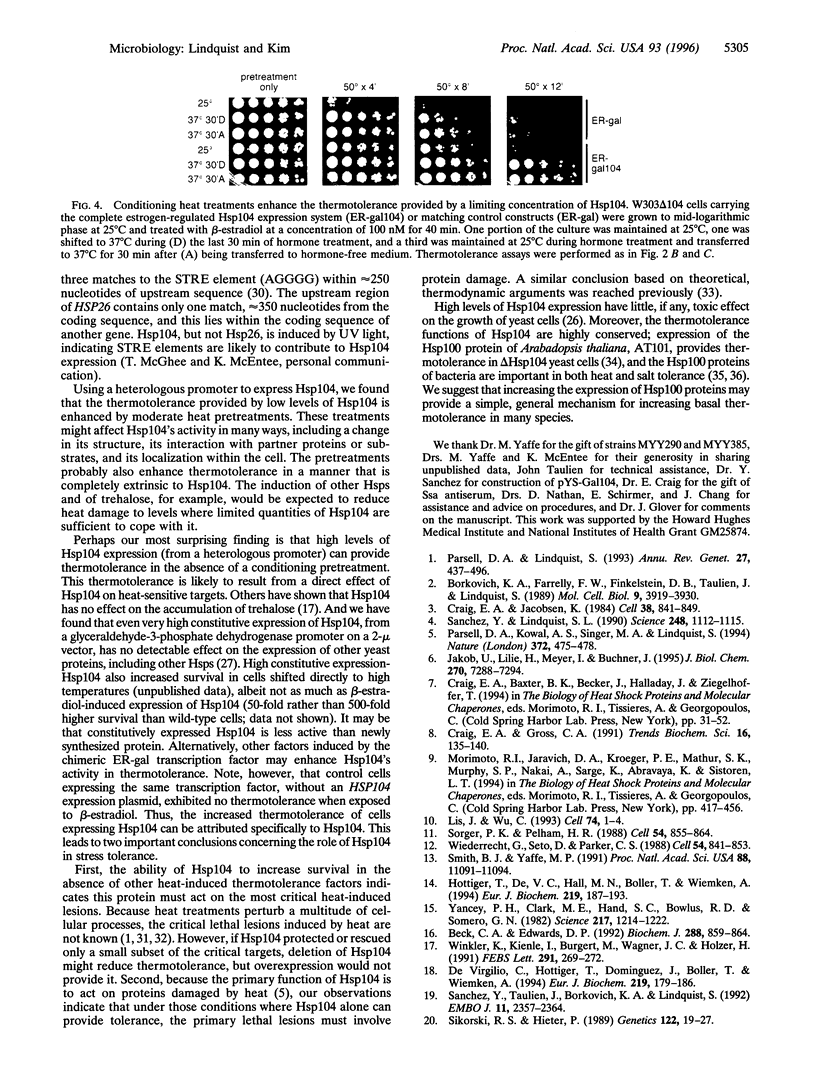

In all organisms, mild heat pretreatments induce tolerance to high temperatures. In the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, such pretreatments strongly induce heat-shock protein (Hsp) 104, and hsp104 mutations greatly reduce high-temperature survival, indicating Hsp1O4 plays a critical role in induced thermotolerance. Surprisingly, however, a heat-shock transcription factor mutation (hsf1-m3) that blocks the induction of Hsps does not block induced thermotolerance. To resolve these apparent contradictions, we reexamined Hsp expression in hsf1-m3 cells. HsplO4 was expressed at a higher basal level in this strain than in other S. cerevisiae strains. Moreover, whereas the hsf1-m3 mutation completely blocked the induction of Hsp26 by heat, it did not block the induction of Hsp1O4. HSP104 could not be deleted in hsf1-m3 cells because the expression of heat-shock factor (and the viability of the strain) requires nonsense suppression mediated by the yeast prion [PSI+], which in turn depends upon Hsp1O4. To determine whether the level of Hsp1O4 expressed in hsf1-m3 cells is sufficient for thermotolerance, we used heterologous promoters to regulate Hsp1O4 expression in other strains. In the presence of other inducible factors (with a conditioning pretreatment), low levels of Hsp1O4 are sufficient to provide full thermotolerance. More remarkably, in the absence of other inducible factors (without a pretreatment), high levels of Hsp1O4 are sufficient. We conclude that Hsp1O4 plays a central role in ameliorating heat toxicity. Because Hsp1O4 is nontoxic and highly conserved, manipulating the expression of Hsp1OO proteins provides an excellent prospect for manipulating thermotolerance in other species.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Borkovich K. A., Farrelly F. W., Finkelstein D. B., Taulien J., Lindquist S. hsp82 is an essential protein that is required in higher concentrations for growth of cells at higher temperatures. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Sep;9(9):3919–3930. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.9.3919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernoff Y. O., Lindquist S. L., Ono B., Inge-Vechtomov S. G., Liebman S. W. Role of the chaperone protein Hsp104 in propagation of the yeast prion-like factor [psi+]. Science. 1995 May 12;268(5212):880–884. doi: 10.1126/science.7754373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig E. A., Gross C. A. Is hsp70 the cellular thermometer? Trends Biochem Sci. 1991 Apr;16(4):135–140. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90055-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig E. A., Jacobsen K. Mutations of the heat inducible 70 kilodalton genes of yeast confer temperature sensitive growth. Cell. 1984 Oct;38(3):841–849. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Virgilio C., Hottiger T., Dominguez J., Boller T., Wiemken A. The role of trehalose synthesis for the acquisition of thermotolerance in yeast. I. Genetic evidence that trehalose is a thermoprotectant. Eur J Biochem. 1994 Jan 15;219(1-2):179–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hottiger T., De Virgilio C., Hall M. N., Boller T., Wiemken A. The role of trehalose synthesis for the acquisition of thermotolerance in yeast. II. Physiological concentrations of trehalose increase the thermal stability of proteins in vitro. Eur J Biochem. 1994 Jan 15;219(1-2):187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb19929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob U., Lilie H., Meyer I., Buchner J. Transient interaction of Hsp90 with early unfolding intermediates of citrate synthase. Implications for heat shock in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1995 Mar 31;270(13):7288–7294. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N., McEntee K. Evidence for a heat shock transcription factor-independent mechanism for heat shock induction of transcription in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(17):6550–6554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krüger E., Völker U., Hecker M. Stress induction of clpC in Bacillus subtilis and its involvement in stress tolerance. J Bacteriol. 1994 Jun;176(11):3360–3367. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3360-3367.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo A. The effects of hyperthermia on mammalian cell structure and function. Cell Prolif. 1992 Mar;25(2):59–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.1992.tb01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis J., Wu C. Protein traffic on the heat shock promoter: parking, stalling, and trucking along. Cell. 1993 Jul 16;74(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louvion J. F., Havaux-Copf B., Picard D. Fusion of GAL4-VP16 to a steroid-binding domain provides a tool for gratuitous induction of galactose-responsive genes in yeast. Gene. 1993 Sep 6;131(1):129–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90681-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mager W. H., De Kruijff A. J. Stress-induced transcriptional activation. Microbiol Rev. 1995 Sep;59(3):506–531. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.506-531.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves M. J., François J. On the mechanism by which a heat shock induces trehalose accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem J. 1992 Dec 15;288(Pt 3):859–864. doi: 10.1042/bj2880859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell D. A., Kowal A. S., Lindquist S. Saccharomyces cerevisiae Hsp104 protein. Purification and characterization of ATP-induced structural changes. J Biol Chem. 1994 Feb 11;269(6):4480–4487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell D. A., Kowal A. S., Singer M. A., Lindquist S. Protein disaggregation mediated by heat-shock protein Hsp104. Nature. 1994 Dec 1;372(6505):475–478. doi: 10.1038/372475a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell D. A., Lindquist S. The function of heat-shock proteins in stress tolerance: degradation and reactivation of damaged proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1993;27:437–496. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.27.120193.002253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsell D. A., Sanchez Y., Stitzel J. D., Lindquist S. Hsp104 is a highly conserved protein with two essential nucleotide-binding sites. Nature. 1991 Sep 19;353(6341):270–273. doi: 10.1038/353270a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petko L., Lindquist S. Hsp26 is not required for growth at high temperatures, nor for thermotolerance, spore development, or germination. Cell. 1986 Jun 20;45(6):885–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90563-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg B., Kemeny G., Switzer R. C., Hamilton T. C. Quantitative evidence for protein denaturation as the cause of thermal death. Nature. 1971 Aug 13;232(5311):471–473. doi: 10.1038/232471a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi J. M., Lindquist S. The intracellular location of yeast heat-shock protein 26 varies with metabolism. J Cell Biol. 1989 Feb;108(2):425–439. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.2.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y., Lindquist S. L. HSP104 required for induced thermotolerance. Science. 1990 Jun 1;248(4959):1112–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.2188365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez Y., Taulien J., Borkovich K. A., Lindquist S. Hsp104 is required for tolerance to many forms of stress. EMBO J. 1992 Jun;11(6):2357–2364. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05295.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schirmer E. C., Lindquist S., Vierling E. An Arabidopsis heat shock protein complements a thermotolerance defect in yeast. Plant Cell. 1994 Dec;6(12):1899–1909. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.12.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989 May;122(1):19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith B. J., Yaffe M. P. Uncoupling thermotolerance from the induction of heat shock proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Dec 15;88(24):11091–11094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorger P. K., Pelham H. R. Yeast heat shock factor is an essential DNA-binding protein that exhibits temperature-dependent phosphorylation. Cell. 1988 Sep 9;54(6):855–864. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires C. L., Pedersen S., Ross B. M., Squires C. ClpB is the Escherichia coli heat shock protein F84.1. J Bacteriol. 1991 Jul;173(14):4254–4262. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4254-4262.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel J. L., Parsell D. A., Lindquist S. Heat-shock proteins Hsp104 and Hsp70 reactivate mRNA splicing after heat inactivation. Curr Biol. 1995 Mar 1;5(3):306–317. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederrecht G., Seto D., Parker C. S. Isolation of the gene encoding the S. cerevisiae heat shock transcription factor. Cell. 1988 Sep 9;54(6):841–853. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler K., Kienle I., Burgert M., Wagner J. C., Holzer H. Metabolic regulation of the trehalose content of vegetative yeast. FEBS Lett. 1991 Oct 21;291(2):269–272. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)81299-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancey P. H., Clark M. E., Hand S. C., Bowlus R. D., Somero G. N. Living with water stress: evolution of osmolyte systems. Science. 1982 Sep 24;217(4566):1214–1222. doi: 10.1126/science.7112124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]