Abstract

Background

Few useful patient-reported outcomes scales for functional dyspepsia exist in China.

Aims

The purpose of this work was to translate and cross-culturally adapt the Functional Digestive Disorders Quality of Life Questionnaire (FDDQL) from the English version to Chinese (in Mandarin).

Methods

The following steps were performed: forward translations, synthesis of the translations, backward translations, pre-testing and field testing of FDDQL. Reliability, validity, responsiveness, confirmatory factor analysis, item response theory and differential item functioning of the scale were analyzed.

Results

A total of 300 functional dyspepsia patients and 100 healthy people were included. The total Cronbach’s alpha was 0.932, and split-half reliability coefficient was 0.823 with all test–retest coefficients greater than 0.9 except Coping With Disease domain. In construct validity analysis, every item correlated higher with its own domain than others. The comparative fit index of FDDQL was 0.902 and root mean square error of approximation was 0.076. Functional dyspepsia patients and healthy people had significant differences in all domains. After treatment, all domains had significant improvements except diet. Item response theory analysis showed the Person separation index of 0.920 and the threshold estimator of items was normally distributed with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.27. The residuals of each item were between −2.5 and 2.5, without statistical significance. Differential item functioning analysis found that items had neither uniform nor non-uniform differential item functioning in different genders and age groups.

Conclusions

The Chinese version of FDDQL has good psychometric properties and is suitable for measuring the health status of Chinese patients with functional dyspepsia.

Keywords: Functional dyspepsia, Quality of life, Translations, Validation studies, Cross-cultural comparison, Health outcomes

Introduction

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is characterized by symptoms including bothersome postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain and scorching heat with no evidence of organic damage [1]. FD is a common condition with a high prevalence throughout the world; according to research it has affected up to 29.2 % of the global population [2, 3]. FD symptoms often impact aspects of the patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQL), these including abdominal pain and indigestion, emotional distress, problems with food and drink, impaired vitality, and heavy economic burdens [4, 5]. Consequently, the HRQL endpoint is critical in assessing the clinical outcomes of FD.

Numerous disease-specific scales have been developed for FD, a few include quality of life in duodenal ulcer patients (QLDUP) [6], quality of life in reflux and dyspepsia (QOLRAD) [7], functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) [8, 9], quality of life in peptic disease (QPD) [10], Nepean dyspepsia index (NDI) [11], and severity of dyspepsia assessment (SODA) [12], etc. So far, no Chinese version of these scales has been translated and validated. Considering that FD is also a very common disease in China, with a high prevalence of up to 18.92 % [13], and also, few useful HRQL instruments for FD exist in clinical research and practice, the introduction of a Chinese FD HRQL instrument is urgent and necessary.

Functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) is a disease specific scale originally developed in French and validated by Chassany Olivier et al. in 1998 [8, 9]. It aims to measure the specific physical, psychological, and perpetual impacts of FD and irritable bowel syndrome. The 5-point Likert scale contains 43 items under eight subheadings, which are activities (8 items), anxiety (5 items), diet (6 items), sleep (3 items), discomfort (9 items), health perceptions (6 items), coping with disease (3 items) and impact of stress (3 items). A higher overall score indicates a better HRQL status. With the validity and reliability being evaluated, it has further been translated into Italian, Hungarian and Spanish, adapted for US, English, French and Canadian patients [8, 14], and applied in many clinical trials [15–17]. This study aims to translate and cross-culturally adapt the English version of FDDQL into Chinese (in Mandarin).

Methods

Participants

Expert Panel

The study group included one coordinator, four translators, three gastroenterologists, two nurses, two HRQL experts and one secretary. The group aimed to conduct and participate in each research stage, with the guidance of moderator (Prof. Liu Feng-bin) during the overall research process and translation procedures.

Patients

According to Rome III diagnostic criteria, functional dyspepsia (FD) must include one or more of the following: (a) bothersome postprandial fullness, (b) early satiation, (c) epigastric pain, and (d) epigastric burning, as well as no evidence of structural tissue damage (including upper endoscopy level) that is likely to explain the symptoms. The FD patients were divided into Postprandial Distress Syndrome (PDS) and Epigastric Pain Syndrome (EPS) as Rome III defined.

The inclusion criteria were: (a) the existence of FD defined by Rome III, (b) age range between 18 and 70 years, and (c) Chinese literate. The following were excluded: pregnant or lactating women, FD patients with disturbance of consciousness, mental illness or other specific diseases who cannot comprehend the scale. The diagnostic, inclusion and exclusion criteria applied for every step in the study.

Permissions for the Use and Translation of FDDQL

The User Agreement (see Appendix 1) and Translation Agreement (see Appendix 2) of English version of FDDQL (see Appendix 3) from MAPI RESEARCH TRUST were obtained by the corresponding author (Prof. Liu Feng-bin) on December 23rd 2008. Meanwhile, permission for the study from the Research Ethics Committees in Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine was also obtained.

Forward Translations

Two Chinese translators (A and B) proficiently fluent in English translated the complete English version of FDDQL, including item content, response options and instructions, into Chinese independently (FWT-A and FWT-B). Translator A was a physician and researcher. His work was intended to produce a translation providing a more reliable equivalence from a measurement perspective. Translator B (naive translator) has no medical background. His task was more focused on highlighting ambiguous meanings in the original questionnaire. They produced written reports summarizing all difficulties encountered, choices made and remaining uncertainties.

Synthesis of the Translations

The aim was to come up with one single version which is accepted by most participators. Coordinated by Prof. Liu Feng-bin, two translations (FWT-A and FWT-B) were merged into one single forward translation (FWT-A/B). The agreements and differences, even if they were very tiny, such as one word or punctuation marks, etc., were identified. The agreements were accepted for further processing, conversely, the differences were discussed item by item by the study group and three FD patients in multi-wave focus group meetings. If the disagreements were too difficult to resolve, alternative wording was suggested in the provisional forward translation for resolution through the backward translation process.

There were seven fully consistent items (Q17, Q19, Q20, Q31, Q33, Q39, Q40) in this step. The other 36 items had differences more or less. Of those, many were distributed on the synonyms, adjectives, prepositions, punctuations, word order, attributive adjuncts, etc. For example, as for Q2 ‘have you had to disrupt your daily activities?’, the FWT-A described as “您的消化问题会影响日常活动吗?”, and FWT-B as “您的消化问题会扰乱您的日常活动吗?”. The words “影响” and “打扰” were synonyms in Chinese, and “您的” additionally defined “日常活动” in FWT-B. The two translations were highly similar. Two-wave focus groups meetings were performed and no disagreements were too difficult to resolve (see Table 1, the FWT-A, FWT-B and FWT-A/B are available by request).

Table 1.

The qualitative research procedure for functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) translation and the results

| Step | Comparisons | Qualitative research | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Versions | Agreements | Disagreements | Methods | Waves | Participants | |

| Synthesis of the translations | FWT-A and FWT-B | 7 items | 36 items | Focus groups | 2 | The study group and three patients |

| Backward translations | a) BWT-C and Original FDDQL | 10 items | 33 items | Expert review | 2 | Seven experts |

| b) BWT-D and Original FDDQL | 15 items | 28 items | ||||

| Pilot testing | BWT-C/D and patients’ advice | 32 items | 11 items | Patients interview | 2 | The study group and 30 patients |

There was no unsolved problem in each step

Backward Translations

Totally blinded to the original English version of FDDQL, two translators (C and D) with a high level of fluency in English translated the single forward translation (FWT-A/B) back into English independently (BWT-C and BWT-D). Translator C was a physician and researcher with the objective to provide equivalency from a more clinical perspective. Translator D (naive translator) has no medical background. His work aimed to detect the more subtle differences in meaning of the original and offer a translation that reflects common Chinese used.

With the help of a translation coordinator, the agreements and differences between backward English translations and the original questionnaire were identified. Then, multi-wave discussions were performed until one single version (BWT-C/D) accepted by most participants was approved for pilot-testing. Challenging phrases, uncertainties and rationale of final decisions were recorded. An expert review (coordinated by Prof. Liu Feng-bin) was conducted to discuss and resolve any ambiguities in each translation version, and then the pilot testing of FDDQL was produced. The results were shown in Table 1. The BWT-C, BWT-D and BWT-C/D are available upon request.

Pilot Testing

The study group interviewed 30 FD patients with different educational levels individually by using a semi-structured questionnaire. The interview focused on items which are difficult, confusing, offensive and alternative questions. Then, the study group discussed the disagreements, comprehension, interpretability and suggestions for improvement, and the field testing for the Chinese version of FDDQL was produced (see Table 1). All the modified versions are available upon request.

Field Testing

Field testing was conducted to collect answers to each question for psychometric validation. A total of 327 consecutive adult patients diagnosed with FD were asked to participate in the study, 300 of them completed the survey. Enrolment started in November 2009 and ended in April 2010 among patients who were attended at the In- and Out-Departments of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine. All the participators had to complete the Chinese version of FDDQL and demographic questionnaire (which contains age, gender, residence, highest education level, disease duration, and disease subtype) once they were enrolled. The reliability, validity, responsiveness, individual items property with item response theory (IRT) and differential item functioning (DIF) analysis of the Chinese version of FDDQL were then psychometrically tested using the collected questionnaires.

Of these, 100 FD patients were asked to answer the questionnaire for a second time, after an interval of 1 or 2 days, to assess the test–retest reliability of the FDDQL. Also, 100 participants who had not previously received therapy and who were to start therapy were asked to answer the questionnaire twice—before replacement therapy, and again 2 weeks after beginning the therapy, to assess the responsiveness of FDDQL. All the patients received the same therapeutic regimen. The 2-week period was adopted because clinical experience has demonstrated that the patients’ health status usually improved significantly with correct interventions in this interval.

In order to assess the criterion validity of FDDQL, the Chronic Gastritis Subscale in Gastroenteric Disease Patient-Reported Outcome Scale (GEDPRO-CG, Chinese Version) would also be completed in the first interview simultaneously by at least 100 FD patients. GEDPRO-CG was a 31-item self-administered instrument to assess the health status of chronic gastritis and FD patients. The 5-point Likert scale contains four domains: physical (19 items), psychological (4 items), independent (4 items) and environment (4 items). Each item scored from 1 (best) to 5 (worst), with higher scores indicating worse health status. The previous studies showed it had good reliability, validity, responsiveness and item properties [18]. Furthermore, 110 healthy people were asked to answer FDDQL to assess its discriminant validity, of those, 100 completed the survey.

Data Analysis

Demographic and clinical variables of the participants were summarized using descriptive analyses. For reliability, the internal consistency reliability, test–retest reliability and split-half reliability were examined. A Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of ≥ 0.70 was considered acceptable for internal consistency. The correlation coefficient of ≥ 0.70 was considered acceptable for test–retest reliability. The half-tests were created by splitting out the odd-numbered items as one half and the even-numbered items as another half. The correlation of scores between the two halves was calculated by using the Spearman-Brown formula. The coefficient of ≥ 0.70 was considered acceptable for split-half reliability [19].

Validity, the construct validity, criterion validity and discriminant validity were examined. For construct validity, correlation analysis and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were performed to test the hypothesized domain structure. Higher correlation coefficient with its own domain rather than other domains indicates good construct validity. Overall and every domain's model fit statistics were examined in CFA, as well as standardized regression coefficients (factor loadings) for each item. Good model fit is indicated when the Bentler comparative fit index (CFI) is above 0.90. In addition, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) should be below 0.05 as an indication of good model fit, or below 0.08 as acceptable model fit [20]. Criterion validity was calculated with Pearson correlation coefficients among all domains of FDDQL and GEDPRO-CG. The correlation values between 0.10 and 0.29 are considered weak, between 0.30 and 0.49 are considered moderate, and between 0.50 and 1.00 are considered strong. Discriminant validity was measured by the between-groups comparison of FD patients and healthy people. Responsiveness was measured by the within-groups comparison of before- and after-treatment in FD patients.

Item response theory (IRT) was a mathematical model-based approach used to understand the relationships between individuals’ HRQL (trait latent) and their response patterns [21]. In IRT, the number of item parameters to be estimated determines which IRT statistical model will be used. IRT models can be divided into two families: unidimensional and multidimensional. Of those, multidimensional IRT models model response data hypothesized to arise from multiple traits. The FDDQL data were fitted to the partial credit model (PCM). Person separation index (PSI) values of 0.90 or greater indicate excellent property, and individual item fit residual statistics were acceptable when the value ranged from −2.5 to +2.5. The item fit residual statistics (short for Fit Resid) was analyzed by chi square with Bonferroni correction [22].

Differential item functioning (DIF) of each item was also evaluated. For a certain item, if distributions of the response from different people with the same HRQL (trait latent) were different, then the item was regarded as having DIF. If the item displayed a constant difference between groups through the whole range of HRQL, then the item was considered displaying a uniform DIF. When the differences occurred only at a certain level, the item displayed a non-uniform DIF. Both uniform DIF and non-uniform DIF were checked.

Data description, reliability, validity and responsiveness of FDDQL were analyzed by SPSS 11.0. CFA was conducted by using Lisrel software (version 8.7) [23]. IRT and DIF analysis was performed with the Rasch Unidimensional Measurement Model software 2020 (RUMM) [24]. All statistical tests were two-tailed, and the level of significance was set at 5 %.

Results

Socio-Demographic and Disease Characteristics

A total of 327 FD patients and 110 healthy people were enrolled in the field study. Of those, 27 patients and ten healthy people who didn’t complete the survey due to inadequate time were excluded. Finally, 300 FD patients and 100 healthy people were engaged in total data analysis. Of those, 100, 100, and 100 patients were included for test–retest reliability, criterion validity and responsiveness analysis, respectively. The socio-demographic and disease characteristics of different group participators are shown in Table 2. There is no missing data in item response. The average completion time of FDDQL was 12.45 ± 3.13 min.

Table 2.

The socio-demographic and disease characteristics of participators in field testing

| Characteristics | Total patients (N = 300) | Test–retest reliability (N = 100) | Criterion validity (N = 100) | Responsiveness (N = 100) | Healthy people (%) (N = 100) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ages (years) | 31.83 ± 27.00 | 32.75 ± 27.00 | 32.81 ± 28.50 | 31.37 ± 27.50 | 30.48 ± 26.76 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 160 (53.3) | 52 (52.0) | 53 (53.0) | 60 (60.0) | 51 (51.0) |

| Female | 140 (46.7) | 48 (48.0) | 47 (47.0) | 40 (40.0) | 49 (49.0) |

| Residence | |||||

| City or town | 267 (89.0) | 87 (87.0) | 87 (87.0) | 87 (87.0) | 85 (85.0) |

| Rural | 33 (11.0) | 13 (13.0) | 13 (13.0) | 13 (13.0) | 15 (15.0) |

| Highest education levels | |||||

| Less than high education | 79 (26.3) | 28 (28.0) | 29 (29.0) | 27 (27.0) | 31 (31.0) |

| High education or above | 221 (73.7) | 72 (72.0) | 71 (71.0) | 73 (73.0) | 69 (69.0) |

| Disease duration (weeks) | 6.89 ± 8.00 | 6.76 ± 8.00 | 6.62 ± 8.00 | 6.81 ± 8.00 | – |

| Functional dyspepsia subtype | |||||

| Postprandial distress syndrome | 178 (59.3) | 55 (55.0) | 58 (58.0) | 60 (60.0) | – |

| Epigastric pain syndrome | 122 (40.7) | 45 (45.0) | 42 (42.0) | 40 (40.0) | – |

Values given as functional dyspepsia patients, n (%)

Reliability

Three hundred patients’ data were used for internal consistency reliability and split-half reliability analysis, and 100 were used for test–retest reliability analysis. The global Cronbach’s α of the Chinese version of FDDQL was 0.932, and coefficients of eight domains ranged from 0.676 to 0.817. The global split-half reliability coefficient was 0.823 and coefficients of eight domains ranged from 0.703 to 0.820. As for test–retest reliability, all domains’ coefficients were greater than 0.9 except the health perceptions domain (r = 0.738) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Scale reliability of Chinese version of functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) (43 items, 8 domains)

| Domains | Cronbachs’ α (N = 300) | Split-half reliability coefficient (N = 300) | Test–retest reliability coefficient (N = 100) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activities (8 items) | 0.806 | 0.820 | 0.980 |

| Anxiety (5 items) | 0.805 | 0.713 | 0.968 |

| Diet (6 items) | 0.817 | 0.781 | 0.967 |

| Sleep (3 items) | 0.676 | 0.735 | 0.961 |

| Discomfort (9 items) | 0.812 | 0.744 | 0.905 |

| Health perceptions (6 items) | 0.751 | 0.703 | 0.738 |

| Coping with disease (3 items) | 0.818 | 0.733 | 0.972 |

| Impact of stress (3 items) | 0.722 | 0.705 | 0.957 |

| Total (43 items) | 0.932 | 0.823 | 0.976 |

Validity

Construct Validity

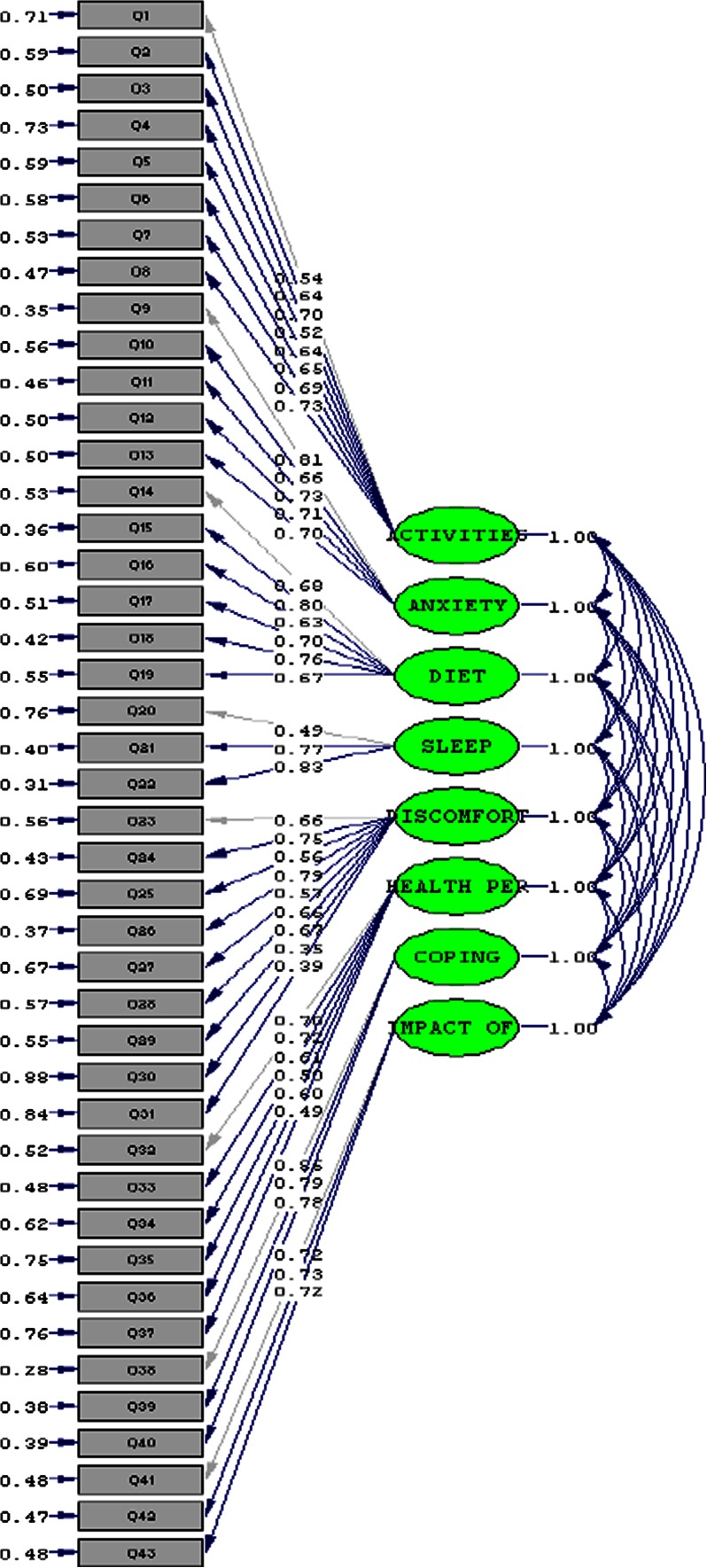

Items–domains correlation analysis showed that all items correlated more strongly with their own domains than with other domains (Table 4). CFA analysis showed the CFI of global FDDQL was 0.902 and RMSEA was 0.076, and the CFI values of activities (0.950), anxiety (0.970), diet (0.960), sleep (0.965), discomfort (0.910), health perceptions (0.940), coping with disease (0.920) and impact of stress (0.905) domains were all greater than 0.9 (see Fig. 1, and the complete CFA results are available upon request).

Table 4.

Items–domains correlation analysis of Chinese version of functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) (43 items, 8 domains, N = 300)

| Questions | Activities (8 items) | Anxiety (5 items) | Diet (6 items) | Sleep (3 items) | Discomfort (9 items) | Health perceptions (6 items) | Coping with disease (3 items) | Impact of stress (3 items) | Total (43 items) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | −0.565** | −0.314** | −0.290** | −0.294** | −0.257** | −0.302** | −0.323** | −0.130* | −0.445** |

| Q2 | −0.638** | −0.297** | −0.452** | −0.328** | −0.481** | −0.328** | −0.228** | −0.139* | −0.538** |

| Q3 | −0.682** | −0.383** | −0.379** | −0.292** | −0.335** | −0.253** | −0.114* | −0.117* | −0.473** |

| Q4 | −0.591** | −0.243** | −0.203** | −0.183** | −0.203** | −0.280** | −0.276** | −0.304** | −0.373** |

| Q5 | −0.656** | −0.376** | −0.297** | −0.251** | −0.321** | −0.301** | −0.332** | −0.282** | −0.489** |

| Q6 | −0.654** | −0.410** | −0.322** | −0.315** | −0.321** | −0.258** | −0.283** | −0.204** | −0.483** |

| Q7 | −0.690** | −0.373** | −0.353** | −0.260** | −0.325** | −0.324** | −0.281** | −0.226** | −0.500** |

| Q8 | −0.746** | −0.487** | −0.415** | −0.355** | −0.391** | −0.374** | −0.337** | −0.240** | −0.597** |

| Q9 | −0.486** | −0.785** | −0.447** | −0.310** | −0.392** | −0.331** | −0.339** | −0.326** | −0.597** |

| Q10 | −0.303** | −0.728** | −0.396** | −0.348** | −0.324** | −0.296** | −0.258** | −0.184** | −0.502** |

| Q11 | −0.441** | −0.772** | −0.421** | −0.425** | −0.400** | −0.382** | −0.341** | −0.261** | −0.606** |

| Q12 | −0.399** | −0.736** | −0.508** | −0.374** | −0.373** | −0.395** | −0.303** | −0.273** | −0.582** |

| Q13 | −0.438** | −0.732** | −0.458** | −0.421** | −0.396** | −0.448** | −0.382** | −0.283** | −0.617** |

| Q14 | −0.406** | −0.548** | −0.649** | −0.316** | −0.393** | −0.175** | −0.260** | −0.135* | −0.528** |

| Q15 | −0.381** | −0.526** | −0.781** | −0.336** | −0.391** | −0.321** | −0.277** | −0.248** | −0.583** |

| Q16 | −0.416** | −0.347** | −0.712** | −0.296** | −0.419** | −0.240** | −0.225** | −0.141* | −0.517** |

| Q17 | −0.287** | −0.353** | −0.742** | −0.295** | −0.295** | −0.285** | −0.189** | −0.111 | −0.472** |

| Q18 | −0.349** | −0.358** | −0.782** | −0.316** | −0.398** | −0.404** | −0.234** | −0.190** | −0.556** |

| Q19 | −0.435** | −0.490** | −0.673** | −0.424** | −0.408** | −0.371** | −0.300** | −0.183** | −0.593** |

| Q20 | −0.351** | −0.287** | −0.259** | −0.720** | −0.394** | −0.331** | −0.338** | −0.135* | −0.471** |

| Q21 | −0.290** | −0.416** | −0.406** | −0.811** | −0.366** | −0.341** | −0.312** | −0.175** | −0.532** |

| Q22 | −0.376** | −0.480** | −0.397** | −0.810** | −0.411** | −0.372** | −0.351** | −0.171** | −0.583** |

| Q23 | −0.410** | −0.415** | −0.530** | −0.284** | −0.666** | −0.279** | −0.263** | −0.071 | −0.564** |

| Q24 | −0.274** | −0.360** | −0.375** | −0.340** | −0.679** | −0.289** | −0.281** | −0.191** | −0.520** |

| Q25 | −0.280** | −0.355** | −0.322** | −0.343** | −0.591** | −0.311** | −0.305** | −0.172** | −0.490** |

| Q26 | −0.310** | −0.327** | −0.304** | −0.383** | −0.713** | −0.243** | −0.283** | −0.157** | −0.512** |

| Q27 | −0.292** | −0.355** | −0.360** | −0.330** | −0.601** | −0.215** | −0.296** | −0.234** | −0.480** |

| Q28 | −0.328** | −0.291** | −0.253** | −0.314** | −0.652** | −0.204** | −0.224** | −0.136* | −0.453** |

| Q29 | −0.268** | −0.359** | −0.346** | −0.388** | −0.644** | −0.191** | −0.278** | −0.176** | −0.488** |

| Q30 | −0.359** | −0.213** | −0.255** | −0.223** | −0.581** | −0.390** | −0.326** | −0.149** | −0.452** |

| Q31 | −0.347** | −0.214** | −0.283** | −0.266** | −0.583** | −0.379** | −0.322** | −0.132* | −0.458** |

| Q32 | −0.508** | −0.402** | −0.426** | −0.291** | −0.456** | −0.685** | −0.484** | −0.384** | −0.644** |

| Q33 | −0.330** | −0.391** | −0.305** | −0.379** | −0.359** | −0.722** | −0.497** | −0.358** | −0.579** |

| Q34 | −0.181** | −0.287** | −0.292** | −0.341** | −0.247** | −0.659** | −0.370** | −0.318** | −0.465** |

| Q35 | −0.282** | −0.238** | −0.103 | −0.200** | −0.220** | −0.602** | −0.419** | −0.225** | −0.411** |

| Q36 | −0.296** | −0.377** | −0.342** | −0.291** | −0.304** | −0.704** | −0.309** | −0.264** | −0.521** |

| Q37 | −0.251** | −0.279** | −0.173** | −0.286** | −0.176** | −0.634** | −0.326** | −0.209** | −0.413** |

| Q38 | −0.355** | −0.339** | −0.264** | −0.369** | −0.377** | −0.545** | −0.868** | −0.532** | −0.597** |

| Q39 | −0.370** | −0.362** | −0.282** | −0.326** | −0.439** | −0.483** | −0.844** | −0.450** | −0.592** |

| Q40 | −0.351** | −0.410** | −0.322** | −0.401** | −0.355** | −0.506** | −0.857** | −0.441** | −0.601** |

| Q41 | −0.274** | −0.246** | −0.187** | −0.171** | −0.225** | −0.378** | −0.437** | −0.798** | −0.380** |

| Q42 | −0.281** | −0.266** | −0.223** | −0.093 | −0.201** | −0.282** | −0.383** | −0.800** | −0.360** |

| Q43 | −0.218** | −0.332** | −0.154** | −0.219** | −0.176** | −0.386** | −0.505** | −0.814** | −0.410** |

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01

Fig. 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis of global functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) (43 items, question 1–43)

Criterion Validity

The criterion validity of the Chinese version of FDDQL was assessed by the correlations with GEDPRO-CG. It should be noted that higher scores on FDDQL indicate better quality of life, while higher scores on GEDPRO-CG indicate worse health status. Consequently, strong negative correlations indicate good criterion validity. Almost all the Spearman rank correlation coefficients (86.11 %) were statistically significant (p < 0.05). The two most strongly correlated FDDQL with GEDPRO-CG were those for activities and psychological domains (r = −0.73), and the two weakest correlated domains were impact of stress in FDDQL and psychological in GEDPRO-CG (r = −0.13) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Criterion validity analysis between the Chinese version of the functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) and chronic gastritis subscale in the gastroenteric disease patient-reported outcome scale (GEDPRO-CG, Chinese version, 31 items, 4 domains) (N = 100)

| Domains | Chronic gastritis subscale in the gastroenteric disease patient-reported outcome scale (GEDPRO-CG) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical (19 items) | Psychological (4 items) | Independent (4 items) | Environmental (4 items) | |

| FDDQL | ||||

| Activities (8 items) | −0.60† | −0.73† | −0.38† | −0.43† |

| Anxiety (5 items) | −0.49† | −0.66† | −0.29† | −0.47† |

| Diet (6 items) | −0.46† | −0.50† | −0.17 | −0.26† |

| Sleep (3 items) | −0.48† | −0.39† | −0.37† | −0.39† |

| Discomfort (9 items) | −0.46† | −0.55† | −0.33† | −0.38† |

| Health perceptions (6 items) | −0.35† | −0.37† | −0.16 | −0.24† |

| Coping with disease (3 items) | −0.40† | −0.46† | −0.30† | −0.33† |

| Impact of stress (3 items) | −0.24† | −0.13 | −0.16 | −0.14 |

| Total (43 items) | −0.65† | −0.75† | −0.39† | −0.49† |

* Higher scores on the FDDQL indicate better quality of life, while higher scores on the GEDPRO-CG indicate worse health status. Consequently, strong negative correlations indicate good criterion validity

† p < 0.05

Discriminant Validity

The discriminant validity was assessed by comparing FDDQL scores between FD patients and healthy people. There were no significant differences on the age (p = 0.766), gender (p = 0.686), residence (p = 0.286) and highest education levels (n = 0.365) between the FD patients and healthy people. Scores for each domain ranged from 0 (poor quality of life) to 100 (good quality of life), and the healthy people have higher scale mean scores. All the domains’ differences between FD patients and healthy people were significant (p < 0.001) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Discriminant validity analysis of the Chinese version of the functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) (43 items, 8 domains) with functional dyspepsia patients and healthy people (N = 100)

| Domains | Scores | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional dyspepsia patients | Healthy people | |||

| Activities | 75.4 ± 11.7 | 93.6 ± 3.2 | 24.21 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 58.0 ± 15.7 | 91.6 ± 4.9 | 32.63 | <0.001 |

| Diet | 61.4 ± 16.2 | 86.8 ± 5.9 | 22.91 | <0.001 |

| Sleep | 66.5 ± 17.8 | 90.4 ± 8.2 | 18.21 | <0.001 |

| Discomfort | 63.3 ± 13.9 | 90.7 ± 4.0 | 30.41 | <0.001 |

| Health perceptions | 46.1 ± 17.6 | 91.3 ± 5.2 | 39.61 | <0.001 |

| Coping with disease | 50.9 ± 22.5 | 91.4 ± 7.4 | 27.04 | <0.001 |

| Impact of stress | 45.9 ± 19.8 | 91.7 ± 6.0 | 35.53 | <0.001 |

| Total | 60.8 ± 11.7 | 91.0 ± 2.3 | 41.64 | <0.001 |

Responsiveness

The mean change in FDDQL domain scores from baseline to 2 weeks indicates statistically significant changes (p < 0.05) (Table 7). Of those, the SLEEP domain demonstrated the greatest change in patient-perceived quality of life, with mean change scores of 10.42 ± 1.19 (p < 0.001). The effect sizes (ES) of FDDQL from baseline to 2 weeks was 0.49 and the standardized response mean (SRM) was 1.04.

Table 7.

Responsiveness analysis of the Chinese version of the functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) (43 items, 8 domains) (N = 100)

| Domains | ±s | t | p | SEM | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activities | 6.66 ± 0.56 | 11.973 | <0.001 | 1.189 | 0.569 |

| Anxiety | 9.95 ± 0.89 | 11.192 | <0.001 | 1.118 | 0.634 |

| Diet | −2.67 ± 0.75 | −3.565 | 0.001 | 0.356 | 0.165 |

| Sleep | 10.42 ± 1.19 | 8.778 | <0.001 | 0.876 | 0.585 |

| Discomfort | 8.22 ± 0.88 | 9.314 | <0.001 | 0.934 | 0.591 |

| Health perceptions | 2.33 ± 1.12 | 2.076 | 0.041 | 0.208 | 0.132 |

| Coping with disease | 7.83 ± 1.48 | 5.298 | <0.001 | 0.529 | 0.348 |

| Impact of stress | 4.25 ± 1.37 | 3.094 | 0.003 | 0.310 | 0.215 |

| Total | 5.74 ± 0.55 | 10.39 | <0.001 | 1.044 | 0.491 |

SEM standardized response means, ES effect sizes

Item Response Theory and Differential Item Functioning Analysis

All the items fitted for the IRT analysis and partial credit model (PCM) were used. The PSI was equal to 0.920. The threshold estimator of the items showed in the third column of Table 8 was normally distributed with a mean of 0 and SD of 1.27. The threshold estimator of item 31 was minimum (Q31 = −2.04), which meant that “have you been satisfied with your digestion?” was the most easy item for FD patients to get a high score. The threshold estimator of item 3 was maximum (Q3 = 2.30), which meant that FD patients had the greatest difficulty in getting a high score for “have you had any difficulties carrying out your leisure activities”. The residuals of each item were between −2.5 and 2.5, with no statistical significance, which also meant the model was consistent with the theoretical model (the fourth and fifth column of Table 7). All the factor loadings of items were statistically significant, and almost all of them were greater than 0.4 (see the second column of Table 8). The structural plot of observed variables and latent variables are shown in Fig. 1. As we all know, DIF contains uniform and non-uniform DIF. The analysis in this study found that the items of the Chinese version of FDDQL had neither uniform nor non-uniform DIF in different genders and age groups (≤30, 31–44, ≥45 years).

Table 8.

Confirmatory factor analysis, item response theory and differential item functioning analysis of the Chinese version of the functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (FDDQL) (43 items, 8 domains) (N = 300)

| Questions | Factor loading of CFA | Threshold | Fit Resid | p value | DIFa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Gender | |||||

| Q1 | 0.54 | 1.45 | 0.66 | 0.723 | – | – |

| Q2 | 0.64 | 1.10 | 0.44 | 0.769 | – | – |

| Q3 | 0.70 | 2.30 | 0.92 | 0.541 | – | – |

| Q4 | 0.52 | 1.96 | 0.74 | 0.491 | – | – |

| Q5 | 0.64 | 1.85 | 0.35 | 0.249 | – | – |

| Q6 | 0.65 | 1.77 | 0.24 | 0.329 | – | – |

| Q7 | 0.69 | 1.99 | 0.19 | 0.811 | – | – |

| Q8 | 0.73 | 1.33 | −0.12 | 0.998 | – | – |

| Q9 | 0.81 | −1.55 | −0.81 | 0.384 | – | – |

| Q10 | 0.66 | −0.24 | 0.26 | 0.514 | – | – |

| Q11 | 0.73 | 1.03 | −0.53 | 0.462 | – | – |

| Q12 | 0.71 | −1.00 | −0.80 | 0.040 | – | – |

| Q13 | 0.70 | −0.60 | −1.00 | 0.034 | – | – |

| Q14 | 0.68 | −0.73 | 0.08 | 0.086 | – | – |

| Q15 | 0.80 | −0.72 | −0.78 | 0.359 | – | – |

| Q16 | 0.63 | 0.24 | 1.98 | 0.170 | – | – |

| Q17 | 0.70 | −0.85 | 1.43 | 0.151 | – | – |

| Q18 | 0.76 | −1.03 | 0.22 | 0.504 | – | – |

| Q19 | 0.67 | 1.42 | −0.10 | 0.147 | – | – |

| Q20 | 0.49 | −0.18 | −0.77 | 0.367 | – | – |

| Q21 | 0.77 | −0.38 | 0.13 | 0.409 | – | – |

| Q22 | 0.83 | 0.70 | −0.81 | 0.255 | – | – |

| Q23 | 0.66 | 1.32 | 0.00 | 0.070 | – | – |

| Q24 | 0.75 | −0.48 | 0.24 | 0.961 | – | – |

| Q25 | 0.56 | 1.45 | −0.26 | 0.423 | – | – |

| Q26 | 0.79 | −0.78 | 1.14 | 0.355 | – | – |

| Q27 | 0.57 | 1.35 | 1.48 | 0.452 | – | – |

| Q28 | 0.66 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.182 | – | – |

| Q29 | 0.67 | 1.34 | 1.30 | 0.393 | – | – |

| Q30 | 0.35 | −1.79 | −1.44 | 0.155 | – | – |

| Q31 | 0.39 | −2.04 | −0.23 | 0.733 | – | – |

| Q32 | 0.70 | −1.18 | −1.29 | 0.130 | – | – |

| Q33 | 0.72 | −1.32 | −0.33 | 0.131 | – | – |

| Q34 | 0.61 | −1.65 | −0.18 | 0.692 | – | – |

| Q35 | 0.50 | −0.71 | 1.18 | 0.008 | – | – |

| Q36 | 0.60 | −1.24 | 0.81 | 0.294 | – | – |

| Q37 | 0.49 | −0.06 | 2.20 | 0.212 | – | – |

| Q38 | 0.65 | −0.81 | 0.27 | 0.349 | – | – |

| Q39 | 0.79 | −0.68 | −0.07 | 0.263 | – | – |

| Q40 | 0.78 | −0.92 | 0.19 | 0.043 | – | – |

| Q41 | 0.72 | 0.83 | −0.23 | 0.152 | – | – |

| Q42 | 0.73 | −1.89 | 0.37 | 0.425 | – | – |

| Q43 | 0.72 | −1.60 | 0.62 | 0.041 | – | – |

DIF differential item functioning, Fit Resid indicates the residual of the item

p value means the p value for the residual of the item; it was compared with 0.05/n

a Absence of uniform DIF and non-uniform DIF

Discussion

The abdominal pain or discomfort caused by functional dyspepsia (FD) results in interference of daily activities and brings considerable anxiety and depression to patients. The assessment of HRQOL of FD patients is essential. The FDDQL scale was developed by a collaboration of French, English and German researchers, and has been widely used in many countries. To date, it has already been translated into English (for Canada, UK, USA), French (for Canada), German (for Germany), Hungarian, Italian (for Italy), Russian (for Russia) and Spanish (for Spain). Due to the growing number of FD patients, it has become an absolute necessity to develop or introduce a scale with adequate psychometric characteristics for the quality of life measurement. So, the development of the Chinese version of the FDDQL was necessary. Self-evaluation of the QOL by the patients might provide insight into appropriate measures for patient treatment and care. Also, this study describes a translation and validation process of FDDQL to Chinese (see Appendices 4 and 5).

Psychometric Properties

The Chinese version of the FDDQL has good reliability. Internal reliability analysis showed the Cronbachs’ α of global FDDQL was excellent (0.932), with each domain greater than 0.7 except sleep (0.676). This may be caused by the fewer number of items (3 items). The results were consistent with previous studies in which Cronbachs’ α ranged from 0.69 to 0.89 [3]. The split-half reliability coefficient of the Chinese version of FDDQL was 0.823 with each domain greater than 0.7. As for test–retest reliability analysis, all the coefficients of FDDQL domains were greater than 0.9 except coping with disease (0.738).

In validity analysis, the correlation coefficients of all the items with their own domains were significantly higher than the others. In addition, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) model was used to reflect the relationship between latent variable and items. The CFA showed the determination coefficient was 0.42 which means the structure model explained 42 % variation of the dependent variable. CFI of the overall model was 0.902 and RMSEA was 0.076, which indicated the model was consistent with the theoretical construct. As for criterion validity, it was mainly supported by the pattern of correlation between FDDQL and GEDPRO-CG. The GEDPRO-CG scale was developed in standard procedure which contains physical, psychological, independent and environment domains. The physiology and psychology domains of FDDQL had significant high correlation coefficients with the physical and psychological domains of GEDPRO-CG, in contrast to independent and environmental domains of GEDPRO-CG. This was consistent with the original research [3]. Also, the discriminant capacity of the FDDQL questionnaire was excellent because the patients reported significantly lower scores than healthy people.

The responsiveness of FDDQL was also confirmed. After FD patients received treatments, their symptoms and psychological status were improved, and almost all domain scores increased significantly. The result was similar with the previous study in which people had significantly increased scores in most FDDQL domains after 7 days intervention [25].

The Person separation index (PSI) of FDDQL was 0.920. The threshold estimator of items was normally distributed with a mean of 0 and SD of 1.27. The residuals of items were between −2.5 and 2.5, with no statistical significance. All the items were invariant (no item has uniform or non-uniform DIF) in different genders and age groups (≤30, 31–44, ≥45 years old). This means FD patients in different genders and age groups respond similarly when they suffer from similar severity disease.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study is that the questionnaire that was psychometric evaluated with internal consistency reliability, test–retest reliability, split-half reliability, construct validity, criterion validity, discriminant validity, responsiveness, confirmatory factor analysis, item response theory and differential item functioning analysis. The assessment aspects were comprehensive and all the results indicated the Chinese version of FDDQL has good properties. The other strength is that the questionnaire was translated with a rigorous procedure, which includes study group establishment, permissions acquisition, forward translations, synthesis of the translations, backward translations, pilot testing and field testing. The comprehensive psychometric evaluation methods and rigorous translation procedure ensured the Chinese version of FDDQL was scientific and convincing.

The main limitation of the study is that the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) patients, another intended population for FDDQL, were not included; however, further studies with IBS patients were in progress.

Conclusion

The Chinese version (in Mandarin) of functional digestive disorders quality of life questionnaire (Chi-FDDQL) was translated according to the standard process, including specifically forward-translation, backward-translation, pilot testing and field testing. The survey data indicate Chi-FDDQL has good reliability, validity, responsiveness and other psychometric characteristics with item response theory and different item function analysis. We recommend that Chi-FDDQL can be applied to measure the health status of Chinese FD patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Nelson Xie (University of Sydney, Australia) and Bobby Wong (USA) for their assistance in revising this manuscript critically. This work has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81073163).

Conflict of interest

None.

Appendix 1: The User-Agreement of the Functional Digestive Disorders Quality of Life Questionnaire

Appendix 2: The Translation-Agreement of the Functional Digestive Disorders Quality of Life Questionnaire

Appendix 3: The Original English Version of the Functional Digestive Disorders Quality of Life Questionnaire

Appendix 4: The Final Chinese Version of the Functional Digestive Disorders Quality of Life Questionnaire

Appendix 5: The User Guide for the Chinese Version of the Functional Digestive Disorders Quality of Life Questionnaire

Footnotes

Hou Zheng-kun is the co-first author.

Contributor Information

Liu Feng-bin, Phone: +86-20-36591109, Email: liufb163@163.com.

Jin Yong-xing, Email: 223042515@qq.com.

Wu Yu-hang, Email: 6079476@qq.com.

Hou Zheng-kun, Email: fenghou5128@126.com.

Chen Xin-lin, Email: chenxlsums@126.com.

References

- 1.Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1466–1479. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2661–2666. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i17.2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The prevalence and risk factors of functional dyspepsia in a multiethnic population in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2210–2216. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brun Rita, Kuo Braden. Functional dyspepsia. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2010;3:145–164. doi: 10.1177/1756283X10362639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agreus L, Borgquist L. The cost of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia and peptic ulcer disease in Sweden. Pharmacoeconomics. 2002;20:347–355. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200220050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin C, Marquis P, Bonfils S. A quality of life questionnaire adapted to duodenal ulcer therapeutic trials. Scand J Gastroenterolgy. 1994;206:40. doi: 10.3109/00365529409091420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiklund IK, Junghard O, Grace E, et al. Quality of life in reflux and dyspepsia patients. Psychometric documentation of a new disease-specific questionnaire (QOLRAD) Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998;583:41–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chassany O, Marquis P, Scherrer B, et al. Validation of a specific quality of life questionnaire for functional digestive disorders. Gut. 1999;44:527–533. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.4.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chassany O, Bergmann JF. Quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome, effect of therapy. Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998;583:81–86. doi: 10.1080/11024159850191300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bamfi F, Olivieri A, Arpinelli F, et al. Measuring quality of life in dyspeptic patients: development and validation of a new specific health status questionnaire: final report from the Italian QPD project involving 4000 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:730–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Talley NJ, Haque M, Wyeth JW, et al. Development of a new dyspepsia impact scale: the Nepean Dyspepsia Index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:225–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rabeneck L, Cook KF, Wristers K, Souchek J, Menke T, Wray NP. SODA (severity of dyspepsia assessment): a new effective outcome measure for dyspepsia-related health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:755–765. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00365-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Min-hu C, Bi-hui Z, Chu-jun L, Xiao-zhong P, Pin-jin H. An Epidemiological study on dyspepsia in Guangdong area. Chin J Intern Med. 1998;37:312–314. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buzas GM. Assessment of quality of life in functional dyspepsia. Validation of a questionnaire and its use in clinical practice. Orv Hetil. 2004;145:687–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabate JM, Veyrac M, Mion F, et al. Relationship between rectal sensitivity, symptoms intensity and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:484–490. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03759.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider A, Weiland C, Enck P, et al. Neuroendocrinological effects of acupuncture treatment in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Complement Ther Med. 2007;15:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider A, Enck P, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture treatment in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:649–654. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang YD. Development and evaluation of the chronic gastritis subscale in gastroenteric disease PRO scale (SSDPRO-CG) Guangzhou: Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown GTL, Glasswell K, Harland D. Accuracy in the scoring of writing: studies of reliability and validity using a new zeal and writing assessment system. Assess Writi. 2004;9:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.asw.2004.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct Equ Model. 2002;9:233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rasch G. Studies in mathematical psychology: probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests. Denmark: Danish Institute for Educational Research; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masters GN. A Rasch model for partial credit scoring. Psychometrika. 1982;47:149–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02296272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL 8.7 for Windows [computer software] Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrich, D. Rasch unidimensional measurement models (RUMM) 2020 (Version 4.0). Perth: Rumm Laboratory Pty Ltd; 2003.

- 25.Buzás GM. Quality of life in patients with functional dyspepsia: short- and long-term effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication with pantoprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin or cisapride therapy: a prospective, parallel-group study. Curr Ther Res. 2006;67:305–320. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]