Abstract

Objectives. We examined the impact of Arizona’s “Supporting Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act” (SB 1070, enacted July 29, 2010) on the utilization of preventive health care and public assistance among Mexican-origin families.

Methods. Data came from 142 adolescent mothers and 137 mother figures who participated in a quasi-experimental, ongoing longitudinal study of the health and development of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their infants (4 waves; March 2007–December 2011). We used general estimating equations to determine whether utilization of preventive health care and public assistance differed before versus after SB 1070’s enactment.

Results. Adolescents reported declines in use of public assistance and were less likely to take their baby to the doctor; compared with older adolescents, younger adolescents were less likely to use preventive health care after SB 1070. Mother figures were less likely to use public assistance after SB 1070 if they were born in the United States and if their post–SB 1070 interview was closer to the law’s enactment.

Conclusions. Findings suggest that immigration policies such as SB 1070 may contribute to decreases in use of preventive health care and public assistance among high-risk populations.

Psychosocial stressors adversely affect health, are socially patterned, and contribute to health disparities.1–3 Most research on stress has focused on exposure to individual stressors, but evidence is growing that macro stressors—large-scale events such as disasters, economic recessions, military conflict, and terrorist events—can also adversely affect health.4,5 A growing body of research has suggested that public policies that reflect macro-level exclusion can also harm the health of stigmatized populations. For example, state-level policies that discriminate against lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations have been associated with increased risk of psychiatric disorders and suicide among those populations.6–8 Research has also suggested that policies that discriminate against immigrant groups can adversely affect their mental health.9,10

According to social stress theory,11 a minority group’s disadvantaged social position in dominant society exposes its members to more stressful conditions and events (e.g., discrimination, macro-level exclusion), and this resultant stress contributes to disparate health risks. Research on exposure to stressors and health has indicated that stress can affect health not only by leading to negative emotions and subsequent physiological changes, but also by changing health behaviors, including the utilization of health care.11 Recent research on discrimination and health, for example, has documented that perceived discrimination by health care providers is associated with delays in seeking treatment, lower adherence to medical regimens, and lower rates of follow-up.12 However, relatively little attention has been given to the impact that recent state-level immigration laws have had on the utilization of health care services among Latino populations, with the exception of a recent study that documented changes in health-seeking behaviors among Latinos in northern Arizona.13 Research on the impact of such state-level policies on public health for Latino individuals living in the United States is particularly important given that Latinos represent a significant portion of the uninsured population and are more likely to be hospitalized for preventable causes than non-Latino Whites.14 Furthermore, a recent study found that by reducing the number of preventable hospitalizations among Latinos to the rates of non-Latino Whites, the United States could have saved approximately $900 million.14

Arizona Senate Bill 1070,15 the Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act, was state legislation that empowered police to detain individuals who were not able to prove their citizenship on request. Opponents of the law argued that it essentially legalized racial and ethnic profiling by law enforcement in the state of Arizona. Since the enactment of SB 1070 in Arizona, other state legislatures have passed similar policies.16 Furthermore, the US Supreme Court upheld a key portion of the law, enabling police officers to request proof of legal immigration status of someone they suspect is undocumented.16

Some research has suggested that although the stated intentions of policies such as SB 1070 are to increase the general feeling of safety among citizens, they actually increase fear among Latino and other minority populations because of racial profiling and harassment from authorities within their communities.10,13,17 One recent study of Arizona’s SB 1070 documented that participants in a predominately Latino community in northern Arizona perceived that their communities were less safe, and health care and community service providers reported a drop in services immediately after the passage of SB 1070.13 Moreover, in a separate study of young adolescents in Arizona, Santos et al.18 documented that awareness of SB 1070 was related to diminished self-esteem via a weaker sense of an American identity. Thus, the potential negative effects of these laws are not restricted to adults.

An example of an immigration policy similar to Arizona’s SB 1070 is California’s Save Our State Initiative (Proposition 187), which passed in 1994 (but was ruled unconstitutional in 1997) and required teachers, medical professionals, and welfare office workers to report individuals suspected of being undocumented to authorities.19 One study of Proposition 187 suggested that prejudice against Mexican-origin individuals was 1 factor that significantly predicted whether White, non-Latino participants favored Proposition 187, independent of (1) their desire for this policy to fully adhere to federal laws about immigration and (2) concerns about economic costs related to undocumented immigrants.20 Thus, social policies such as these may be interpreted as macro forms of discrimination. Additionally, Berk and Schur17 found that the fear of deportation among undocumented Latino families after Proposition 187 resulted in a reduction and, in some cases, cessation of health care utilization.

Limited access to health and public assistance also poses risks to Latino children. It is important to note that Latino children represent the largest group of children of immigrants in the United States, and the population of Latino children is growing at a rapid rate.21 Among children, Mexican-origin youths are less likely than White youths and children of other Latino origins (e.g., Puerto Rican) to have access to and to utilize health care, including preventive well-child visits.22

In response to a documented urgent need for continued research on policies such as SB 1070,13 we examined how the enactment of Arizona SB 1070 on July 29, 2010, was prospectively associated with access to health care and public assistance in a sample from a large metropolitan area in Arizona. We examined the impact of SB 1070 among a high-risk sample of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their mother figures. Mexican-origin adolescent mothers are an important subpopulation to study given that they are at even greater risk for poverty and poor health outcomes than Mexican-origin youths in general23; moreover, their children are at high risk for poor developmental and health outcomes.24

METHODS

We drew data from an ongoing, longitudinal quantitative study of 204 dyads of Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and their mother figures (e.g., mother, grandmother, aunt). The original study purpose was to understand the associations among adolescent mothers’ well-being, cultural processes related to their Mexican-origin ethnicity, and family processes. Although the original intent of the research was not to study the impact of Arizona’s SB 1070, it is consistent with the overall goal of the study to understand the complex interplay of context and well-being, with specific attention to the role of ethnicity at multiple levels of an individual’s experience (e.g., micro-level contexts, such as family, to macro-level contexts, such as policies). We recruited adolescents from schools and community agencies in a large metropolitan city in Arizona. Adolescents were eligible for participation if they identified as being of Mexican origin, were pregnant, were not legally married, were aged 15 to 18 years, and had a mother figure willing to participate in the study. Interviews, consisting primarily of closed-ended survey questions, lasted approximately 2.5 hours; each participant was interviewed separately in either Spanish or English. A rolling data collection strategy was used, with wave 1 (W1) interviews occurring when the adolescent was in her 3rd trimester of pregnancy (March 2007–August 2008); wave 2 (W2), when the adolescent’s child was aged 10 months (February 2008–September 2009); wave 3 (W3), when the child was aged 24 months (April 2009–October 2010); and wave 4 (W4), when the child was aged 36 months (March 2010–December 2011). Each participant received $25 at W1, $30 at W2, $35 at W3, and $40 at W4.

Because of our rolling data collection design, some participants experienced the enactment of SB 1070 (i.e., July 29, 2010) between W2 and W3, and others experienced the enactment of SB 1070 between W3 and W4. As a result, the analytic sample for this study included 142 adolescents and 137 mother figures who were interviewed consistently between W2 and W4, allowing us to identify a clear pre–SB 1070 score (i.e., W2 or W3) and a clear post–SB 1070 score (i.e., W3 or W4).

At W1, adolescent mothers were on average aged 16.85 years (SD = 1.03), and mother figures ranged in age from 24 to 78 years (mean = 41.35; SD = 6.99). The majority of adolescents were US-born (62%), whereas only 28% of mother figures were US-born. The average time between the enactment of SB 1070 and the postinterview for adolescents was 164.34 days (SD = 114.34; range = 1–475 days); for mother figures, the average was 163.39 days (SD = 117.57; range = 0–475 days).

Measures

We assessed three measures of public assistance and health care utilization. First, we measured access to public assistance for both adolescents and mother figures with 1 question at W2, W3, and W4: “In the last 12 months, did (you/your family) receive public assistance or welfare payments?” (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Second, we measured access to routine medical care for the adolescent at W2 (i.e., 10 months postpartum) by asking, “Since your baby was born, have you had a routine physical examination other than pregnancy/delivery related?” (0 = no, 1 = yes). At W3 and W4, adolescents were asked the same question, but in reference to the past year. Third, access to routine medical care for the baby was measured using adolescent reports at W2, W3, and W4 of whether she had taken her child to the doctor for routine medical care since the prior wave (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Data Analysis

Before analysis, we restructured data on the basis of the date of the participant’s interview and the date on which SB 1070 went into effect as law in Arizona (i.e., July 29, 2010) to identify whether W2 data or W3 data would be considered the pre–SB 1070 observation and, likewise, whether W3 or W4 data would be identified as the post–SB 1070 observation. We used general estimating equations in PASW version 18 (PASW Statistics, Chicago, IL) to examine change in the dichotomous outcomes (i.e., public assistance access, adolescent medical care access, and medical care access for baby) over time as a result of SB 1070. This method is an extension of logistic regression that takes into account the nonindependent nature of longitudinal data.25

The first model (model 1) for each outcome examined the main effects of SB 1070 (i.e., time), controlling for age, nativity (0 = born outside of the United States, 1 = US-born), and the number of days between the enactment of SB 1070 and the postinterview (W3 or W4, depending on date of interview). The second model for each outcome (model 2) examined the interactions between SB 1070 (i.e., time) and the 3 covariates to test for moderation and assess whether the effect of SB 1070 was dependent on age, nativity, and recency of SB 1070. We mean centered variables before the creation of interaction terms. Significant interactions and their simple slopes were probed at the mean and at 1 standard deviation above and below the mean of the moderator. Moreover, we graphed these interactions to aid in interpretation.

RESULTS

Percentages of adolescents and mother figures who reported accessing public assistance (adolescent and mother figure reports) and routine medical care for themselves (adolescent reports only) and for the baby (adolescent reports only) are displayed in Table 1. Cramer ϕ effect sizes are shown to reflect the differences in percentages pre– and post–SB 1070 and are interpreted as Pearson correlation coefficient effect sizes (i.e., 0.1 = small, 0.3 = moderate, 0.5 = large). Descriptive statistics suggested small to moderate significant decreases in both adolescent and mother figure access of public assistance after the enactment of SB 1070. Moreover, we found moderate significant decreases in adolescent access to routine medical care (e.g., yearly physicals) and small significant decreases in accessing routine care for the baby.

TABLE 1—

Percentage of Participants Who Reported Utilizing Public Assistance or Medical Care Pre– and Post–SB 1070: Arizona, March 2007–December 2011

| Receipt of Services | Pre–SB 1070, % | Post–SB 1070, % | Cramer ϕ |

| Adolescent reports | |||

| Received public assistance | 68 | 56 | 0.37 |

| Accessed routine medical care for self | 51 | 47 | 0.34 |

| Accessed routine medical care for baby | 97 | 90 | 0.24 |

| Mother figure reports receiving public assistance | 45 | 34 | 0.20 |

Note. SB 1070 = Arizona’s “Supporting Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act” (SB 1070, enacted July 29, 2010).

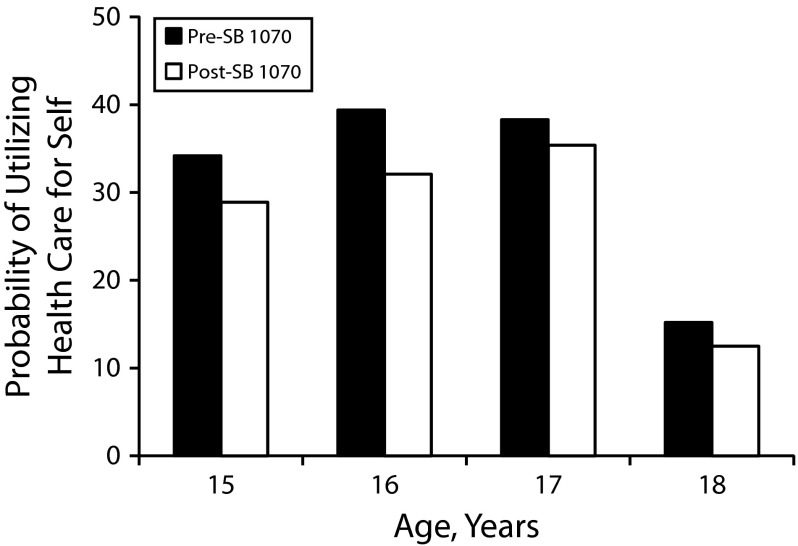

Adolescents

Findings from general estimating equations (Table 2, model 1a) indicated a significant decrease in the receipt of public assistance after the enactment of SB 1070 for Mexican-origin adolescent mothers (b = −0.51; odds ratio [OR] = 0.60; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.39, 0.92). We found no moderation of this effect by age, nativity, or the number of days between the enactment of SB 1070 and the postinterview (model 2a). Although we found no direct effect of SB 1070 on the utilization of preventive health care for the adolescent (model 1c), we found a significant interaction between age and time (model 2c; b = 4.43; P < .05). As shown in Figure 1, younger adolescents experienced a decline in preventive medical care utilization after SB 1070, whereas this decline was not present for older adolescents. Finally, we found a significant decline in adolescents taking the child to receive preventive health care after SB 1070 (model 1d; b = −1.41; OR = 0.24; 95% CI = 0.08, 0.70); this effect was not moderated by age, nativity, or the length of time between SB 1070 and the postinterview (model 2d).

TABLE 2—

Results From General Estimating Equations With Dichotomous Outcomes: Study of Impact of SB 1070 on Utilization of Public Assistance and Preventive Health Care Among Mexican-Origin Families, Arizona, March 2007–December 2011

| Received Public Assistance (AR), b (SE) |

Received Public Assistance (MFR), b (SE) |

Utilized Medical Care for Self (AR), b (SE) |

Utilized Medical Care for Child (AR), b (SE) |

|||||

| Variable | Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 1b | Model 2b | Model 1c | Model 2c | Model 1d | Model 2d |

| Time | −0.51* (0.22) | −0.58 (0.41) | −0.47* (0.24) | −0.18 (0.27) | −0.16 (0.21) | −0.06 (0.39) | −1.41** (0.54) | −1.31 (0.72) |

| Age | 1.37 (1.31) | 1.94 (1.76) | −0.02 (0.20) | 0.02 (0.30) | 2.77* (1.31) | 0.56 (1.73) | −2.71 (2.79) | 0.93 (3.89) |

| Nativity | −0.54 (0.31) | −0.61 (0.41) | −0.67 (0.35) | −0.16 (0.44) | 1.04*** (0.29) | 1.12** (0.37) | 0.58 (0.55) | 0.58 (1.02) |

| Duration | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | −0.01 (0.02) | −0.05* (0.02) | −0.04 (0.03) |

| Time × age | NA | −1.05 (2.28) | NA | −0.09 (0.41) | NA | 4.43* (2.09) | NA | −4.66 (4.31) |

| Time × nativity | NA | 0.11 (0.48) | NA | −1.22* (0.59) | NA | −0.16 (0.46) | NA | 0.05 (1.10) |

| Time × duration | NA | 0.001 (0.02) | NA | 0.05* (0.02) | NA | −0.01 (0.02) | NA | −0.01 (0.03) |

Note. AR = adolescent report; MFR = mother figure report; NA = not applicable; SB 1070 = Arizona’s “Supporting Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act” (SB 1070, enacted July 29, 2010). Time was coded 0 = pre–SB 1070 and 1 = post–SB 1070. Nativity was coded 0 = Mexico-born and 1 = US-born. Duration is the number of days between the enactment of SB 1070 and the postinterview. Age and duration variables were rescaled for analysis by dividing each data point by 10.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

FIGURE 1—

Time × age interaction predicting Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ utilization of medical care for self pre– and post–SB 1070: Arizona, March 2007–December 2011.

Note. SB 1070 = Arizona’s “Supporting Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act” (SB 1070, enacted July 29, 2010). Follow-up analyses revealed a significant decline for younger adolescents (−1 SD; b = 1.05; SE = 0.53; P < .05), but not for older adolescents (+1 SD; b = 0.01; SE = 0.43; P = .99).

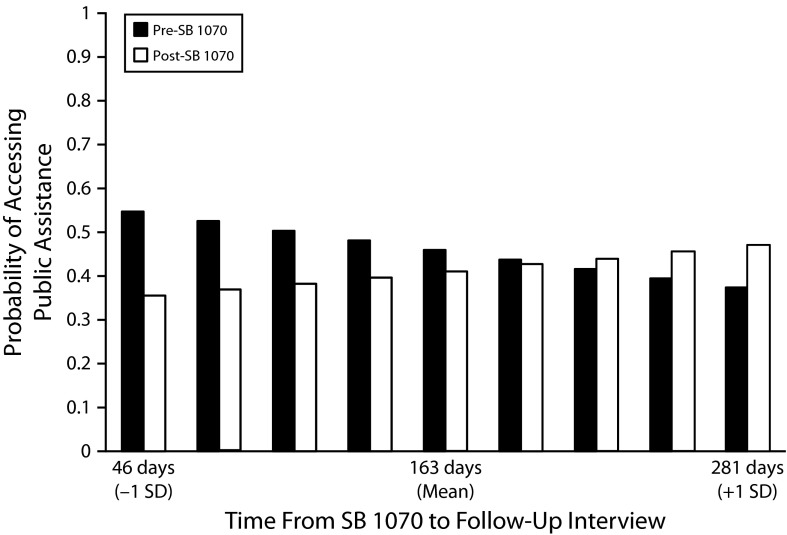

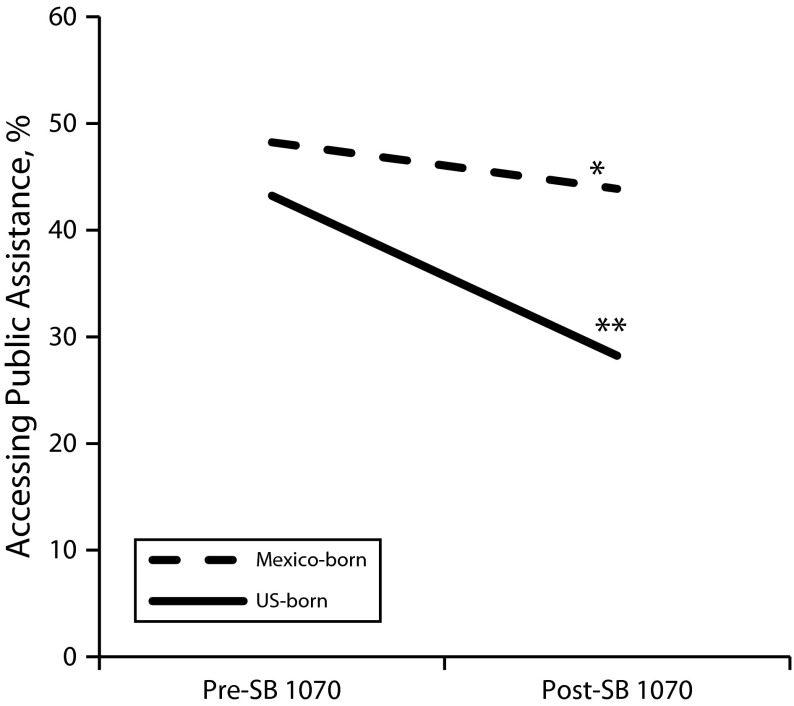

Mother Figures

Similar to findings for adolescents, mother figures’ reports of accessing public assistance significantly decreased after the enactment of SB 1070 (model 1b; b = −0.47; OR = 0.63; 95% CI = 0.39, 0.99). However, as shown in model 2b, this effect was moderated by both nativity (b = −1.22; P < .05) and the number of days between the enactment of SB 1070 and the postinterview (b = 0.05; P < .05). As shown in Figure 2, those interviewed more closely to the enactment of SB 1070 reported a significant decrease in use of public assistance, whereas those interviewed a longer time after the enactment of the legislation reported no change in use of public assistance. As shown in Figure 3, mother figures who were born in the United States reported a steeper decrease in use of public assistance in response to SB 1070 than those who were born outside the United States.

FIGURE 2—

Time × duration interaction predicting mother figures’ utilization of public assistance pre- and post-SB 1070: Arizona, March 2007–December 2011.

Note. SB 1070 = Arizona’s “Supporting Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act” (SB 1070, enacted July 29, 2010). Follow-up analyses revealed a significant decline for mother figures who experienced SB 1070 closer to their postinterview (−1 SD; b = −1.68; SE = 0.53; P < .01), but not for mother figures whose interviews were conducted a longer time after SB 1070 was enacted (+1 SD; b = 0.06; SE = 0.51; P = .91).

FIGURE 3—

Time × nativity interaction predicting mother figures’ utilization of public assistance pre– and post–SB 1070: Arizona, March 2007–December 2011.

Note. SB 1070 = Arizona’s “Supporting Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act” (SB 1070, enacted July 29, 2010). Simple slopes analyses revealed a significant decline for both Mexico-born mother figures (b = −0.63; SE = 0.28; P < .05) and US-born mother figures (b = −1.41; SE = 0.48; P < .01).

*P < .05; **P < .01.

Post Hoc Analyses

To rule out the possibility that participants in our sample simply used fewer services over time, we examined the change in all of our dependent variables from W1 to W2 (before the enactment of SB 1070), with the exception of adolescent reports of taking the child to the doctor (because the child was not yet born at W1). We used the same methods (i.e., general estimating equations, controlling for age and nativity), and we found that adolescents actually reported an increase in use of public assistance (from 63.2% to 80.5%; b = 0.91; SE = 0.21; P < .001) and routine, preventive health care (from 30.9% to 43.0%; b = 0.54; SE = 0.20; P < .01) from W1 to W2, before the enactment of SB 1070. Similarly, mother figures reported an increase in use of public assistance from W1 to W2 (from 51.5% to 68.5%; b = 0.72; SE = 0.21; P < .001). These findings show that decreases in utilization were not characteristic of the sample before the enactment of SB 1070.

DISCUSSION

Many adolescent mothers, particularly those of Mexican origin, experience life stressors and barriers that place them at significant risk for poverty and poor health outcomes.23 Furthermore, given that their children are at high risk for developmental delays and poor health outcomes,24 it is critically important that they be able to access public assistance and routine medical care in an effort to prevent, detect, and intervene in these problematic outcomes. In our multigenerational sample, we found that the enactment of Arizona’s SB 1070 was associated with decreases in the utilization of public assistance and routine, preventive health care, and these effects sometimes varied by age, nativity, and time between the enactment of SB 1070 and the follow-up interview. Consistent with prior research,13 these findings highlight that state-level immigration policies, such as Arizona’s SB 1070, may contribute to decreases in health care and public assistance access and utilization by Mexican-origin families.

We found that utilization of public assistance by Mexican-origin adolescent mothers and preventive, routine health care for the adolescents’ young children decreased after the enactment of SB 1070, regardless of age, nativity, and time between the enactment of the law and the follow-up interview. These findings suggest that SB 1070 is associated with reductions in Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ utilization of public assistance, which is particularly problematic given their disproportionate risk for poor health and poverty.23 We found no difference by nativity, suggesting that although the law was designed to reduce the number of undocumented Mexican immigrants in the state of Arizona, it was equally associated with the health and economic stability of adolescent mothers who were born in the United States. Thus, as was found in a previous study of SB 1070,13 this law is likely associated with heightened perceptions of fear and lack of community safety, even among Mexican-origin adolescent mothers who are US citizens. Moreover, we documented a negative association between SB 1070 on Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ utilization of preventive health care for their young children, which is particularly problematic given that children of adolescent mothers are at risk for poor developmental and health outcomes.24

Age differences also emerged, such that only younger adolescents experienced a decrease in utilization after SB 1070. Health care for adolescents, regardless of age, is critically important, given that preventive, routine care can increase health-promoting behaviors and decrease detrimental behaviors that are often initiated during this developmental period.26 For adolescent mothers, routine preventive health care is critically important, given that some studies have suggested that health maintenance visits can reduce and postpone repeat adolescent pregnancies.27,28 Furthermore, although the participants in our study had already given birth, research has indicated that younger maternal age is associated with greater health risks,29 suggesting the importance of young women receiving regular health care. Perhaps because they are younger, access to health care is managed by a parental figure. As such, given other work that suggests that Mexican-origin adults did not perceive their communities to be safe after the passage of SB 1070,13 it may be the case that Mexican-origin parents who reacted with fear to SB 1070 may limit their younger adolescents’ access to the community, including access to health care.

Among mother figures in the sample, US-born mother figures reported a steeper decline in use of public assistance than foreign-born mother figures. This result is compelling given that it suggests that SB 1070 was more strongly associated with US-born mother figures’ decisions to seek public assistance, even though they are US citizens by birthright. The reasons for this pattern are unclear and deserving of careful investigation in future research. Perhaps the enactment of SB 1070 was more strongly associated with decreased use of public assistance among US-born mother figures because this policy elevated their awareness and fear of deportation and lack of community safety to the already existing high levels among those who were born outside of the United States. This notion is consistent with prior research, which has found that SB 1070 was detrimental to well-being and perceived community safety for all community individuals, not only those who lacked citizenship documentation.13 A second plausible explanation is that the finding reflects group differences in the levels and consequences of the perception of SB 1070 as discriminatory. Studies on the subjective experience of discrimination reveal that victims often have a profound sense of moral violation.30 Because US-born mother figures are likely to have a greater socialization to US norms of justice and equity than those who are foreign-born, the likelihood that they perceived SB 1070 as discriminatory and unfair may be increased, potentially leading to the stronger impact of SB 1070 evidenced for them compared with their Mexico-born counterparts. Indeed, prior research has indicated that foreign-born Latinos tend to report lower levels of perceived discrimination than US-born Latinos.3

Moreover, we found a recency effect for mother figures, such that the decrease in public assistance after SB 1070 was stronger for mothers whose follow-up interviews were conducted more closely to the enactment of the law. It may be the case that the heightened media attention to SB 1070 resulted in more fear and lower perceptions of community safety for mother figure participants, which is similar to findings from another study of SB 1070.13 Additionally, it may be that the negative impact of SB 1070 merely dissipated over time, which is similar to the results of another event-related research study that found that the positive impact of Barack Obama’s election as US president in 2008 for African American college students dissipated over time.31

Taken together, these findings have strong implications for public health practice and future research, given the significant reductions in use of preventive health care and public assistance in response to SB 1070 for the participants in our study. Access to health care, such as preventive routine visits to a primary care practitioner, is critical for public health for all individuals. Yet, studies have documented persistent ethnic and racial disparities in access to medical care, a finding that is particularly true for Mexican-origin children.22 Thus, consistent with other research,11,13 our findings suggest that policies such as Arizona’s SB 1070 may exacerbate the already existing disparities specific to use of preventive health care and public assistance. Our findings also parallel research that has documented an association between ethnic discrimination and poorer health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority youths and adults,12,32 suggesting that individuals may interpret these types of social policies as a macro-level form of discrimination. Nonetheless, future research needs to examine the complex associations among state-level immigration policies, daily experiences of ethnic discrimination, and health and well-being to parcel out the unique influences of each ethnicity-related stressor and make recommendations to policymakers and health care providers.

Limitations

Although this study has several unique strengths (e.g., quasi-experimental, prospective design), it is not without limitations. First, we relied on participants’ self-reported information, which could be informed by social desirability of health care and service utilization behaviors.33 Despite this potential for social desirability, our findings were robust at the bivariate and multivariate level in showing declines in preventive health care and public assistance use after the enactment of SB 1070. Future research could use records from health care and social service providers to address this limitation. Second, the measures used in this study limit its generalizability and our ability to draw strong conclusions about the impact of SB 1070 on health-related behaviors. Nonetheless, our findings still make a useful contribution to the literature given that few studies have empirically examined SB 1070, and prior work has emphasized the critical need for routine care for adolescent mothers, particularly in terms of reducing or postponing repeat adolescent pregnancies.27,28

Third, we could not account for the effects of a 2004 law (Proposition 200, Protect Arizona Now) and a 2007 immigration law (the Legal Arizona Works Act) in our analyses. Although it is only conjecture, it is possible these laws had already reduced Mexican-origin individuals’ use of governmental services and medical care in Arizona, given that these laws require individuals to provide documentation to be eligible to receive public assistance and to work, respectively. Thus, although we did find significant decreases in use of public assistance and routine medical care, the effects might have been stronger had we been able assess the impacts of the 2 previous laws. Similarly, we were unable to account for the effects of specific health policies that were enacted in Arizona in 2010 that may have affected participant’s utilization of public assistance and routine medical care, such as the elimination of coverage of preventive services for adults on Medicaid in Arizona34 and the introduction of a shared family cost plan (previously 100% funded) for Arizona’s Early Intervention Program that provides services to infants and toddlers with developmental delays or disabilities and their families.35 Finally, our quasi-experimental design does not allow us to infer causality because we did not conduct a randomized, controlled evaluation of SB 1070, which would have been impossible.

Conclusions

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this study documents that social policies such as SB 1070 may provide the impetus for Mexican-origin individuals to avoid contact with public providers, such as medical or governmental professionals, perhaps as a result of fear of deportation or perceived lack of safety. More importantly, we documented that the associations between SB 1070 and health care and service utilization were largely robust across participant nativity, suggesting that these types of social policies (aimed at undocumented individuals) have a negative impact on those who are US citizens and all of the privileges associated with citizenship.

These findings have significant implications for public health policy, given that several states are adopting immigration laws similar to Arizona’s SB 1070. As states continue to adopt these policies, more prospective research is needed to examine the holistic impact on the public’s health and well-being. In sum, this study suggests that social policies, such as Arizona’s SB 1070, may further exacerbate the already existing health disparities of ethnic minority individuals in the United States. Thus, social policymakers should consider the negative effects of such policies and reevaluate the effectiveness of these policies in promoting safe and healthy communities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD061376; Principal Investigator: A. J. U.), the US Department of Health and Human Services (APRPA006001; Principal Investigator: A. J. U.), and the Cowden Fund to the School of Social and Family Dynamics at Arizona State University. Additional support for R. B. Toomey was provided by a National Institute of Mental Health National Research Service Award training grant (T32 MH018387).

Human Participant Protection

The study protocol was approved by Arizona State University’s institutional review board.

References

- 1.Thoits PA. Stress and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1 suppl):S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1685–1687. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sternthal MJ, Slopen N, Williams DR. Racial disparities in health: How much does stress really matter? Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):95–113. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharyya MR, Steptoe A. Emotional triggers of acute coronary syndromes: strength of evidence, biological processes, and clinical implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2007;49(5):353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H et al. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(13):982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatzenbuehler ML. The social environment and suicide attempts in lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Pediatrics. 2011;127(5):896–903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. The impact of institutional discrimination on psychiatric disorders in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: a prospective study. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(3):452–459. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.168815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Poverty, migration, and health. In: Lin AC, Harris DR, editors. The Colors of Poverty. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia AS, Keyes DG. Life as an undocumented immigrant: how restrictive local immigration policies affect daily life. 2012. Available at: http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2012/03/pdf/life_as_undocumented.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2012.

- 11.Cohen S, Kessler RC, Gordon LU. Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hardy LJ, Getrich CM, Quezada JC, Guay A, Michalowski RJ, Henley E. A call for further research on the impact of state-level immigration policies on public health. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1250–1254. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frieden TRCenters for Disease Control and Prevention CDC health disparities and inequalities report—United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 201160suppl1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. SB 1070 (Support Our Law Enforcement and Save Our Neighborhoods Act), 49th Leg, 2 Reg. Sess. (Ariz 2010)

- 16. National Council of State Legislatures. U.S. Supreme Court rules on Arizona’s immigration enforcement law. Available at: http://www.ncsl.org. Accessed July 31, 2012.

- 17.Berk ML, Schur CL. The effect of fear on access to care among undocumented Latino immigrants. J Immigr Health. 2001;3(3):151–156. doi: 10.1023/A:1011389105821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos C, Menjivar C, Godfrey E. Effects of SB 1070 on children. In: Magaña L, Lee E, editors. The Case of Arizona’s Immigration Law SB 1070. New York, NY: Springer; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.California: Proposition 187 unconstitutional. Migr News. 1997;4(12) Available at: http://migration.ucdavis.edu/mn/comments.php?id=1391_0_2_0. Accessed July 31, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee Y-T, Ottati V, Hussain I. Attitudes toward “illegal” immigration into the United States: California Proposition 187. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2001;23(4):430–443. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fortney K, Chaudry A. Children of Immigrants: Growing National and State Diversity. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perez VH, Fang H, Inkelas M, Kuo AA, Ortega AN. Access to and utilization of health care by subgroups of Latino children. Med Care. 2009;47(6):695–699. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318190d9e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman SD. Updated estimates of the consequences of teen childbearing for mothers. In: Hoffman SD, Maynard RA, editors. Kids Having Kids: Economic Costs and Social Consequences of Teen Pregnancy. Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borkowski JG, Bisconti T, Weed K, Willard C, Keogh DA, Whitman TL. The adolescent as parent: influences on children’s intellectual, academic, and socioemotional development. In: Borkowski JG, Ramey SL, Bristol-Power M, editors. Parenting and the Child’s World: Influences on Academic, Intellectual, and Social-Emotional Development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall DB, Bailey RL. Modeling and prediction of forest growth variables based on multilevel nonlinear mixed models. For Sci. 2001;47(3):311–321. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozer EM, Irwin CE., Jr . Adolescent and young adult health: from basic health status to clinical interventions. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Sullivan AL, Jacobsen BS. A randomized trial of a health care program for first-time adolescent mothers and their infants. Nurs Res. 1992;41(4):210–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elster AB, Lamb ME, Tavare J, Ralston CW. Medical and psychosocial impact of comprehensive care on adolescent pregnancy and parenthood. JAMA. 1987;258(9):1187–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Vienne CM, Creveuil C, Dreyfus M. Does young maternal age increase the risk of adverse obstetric, fetal and neonatal outcomes: A cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;147(2):151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feagin JR. The continuing significance of race: antiblack discrimination in public places. Am Sociol Rev. 1991;56(1):101–116. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuller-Rowell TE, Burrow AL, Ong AD. Changes in racial identity among African American college students following the election of Barack Obama. Dev Psychol. 2011;47(6):1608–1618. doi: 10.1037/a0025284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA. Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the role of discrimination, ethnic identity, acculturation, and self-esteem. J Adolesc. 2007;30(4):549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulhus DL. Measurement and control of response bias. In: Robison JP, Shaver PR, Wrightsman LS, editors. Measures of Personality and Social Psychological Attitudes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. AHCCCS benefit changes. 2010. Available at: http://www.azahcccs.gov. Accessed March 26, 2013.

- 35.Arizona Department of Economic Security. Family cost participation. Available at: http://www.azdes.gov/AzEIP. Accessed March 26, 2013.