Abstract

Background

In a population-based setting, we aimed to measure the incidence trends of ischemic stroke (IS) thrombolysis, thrombolysis times, proportion of symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH), 30-day case fatality and functional outcomes. We also compared the 12-month functional status between thrombolyzed and nonthrombolyzed patients.

Methods

Using data from the Joinville Population-Based Stroke Registry, we prospectively ascertained a cohort of all thrombolyses done in Joinville citizens, Southern Brazil, from 2005 to 2011. For the definition of sICH we used European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) II criteria.

Results

Over 7 years, 6% (220/3,552) of all IS were thrombolyzed. The thrombolysis incidence increased from 1.4 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.6-2.9] in 2005 to 9.8 (7.3-12.9) per 100,000 population in 2011 (p < 0.0001). The thrombolysis incidence age-adjusted to the world population in 2011 was 11 (8.2-14.3) per 100,000. Only 30% (50/165) were thrombolyzed within 1 h of arrival at hospital. In 7 days, 6.4% (14/220) had sICH and 57% (8/14) of those died. In the 2009-2011 period, a favorable functional outcome [modified Rankin scale (mRS) 0-1] at 12 months among patients who received thrombolysis was more frequent [mRS 0-1; 36% (38/107)] than among patients who did not receive thrombolysis [mRS 0-1; 24% (131/544); p = 0.016]. The logistic regression showed that thrombolyzed IS patients had a more favorable outcome (mRS 0-1; HR 2.13; 95% CI, 1.2-3.7; p < 0.016) than nonthrombolyzed patients.

Conclusion

In a population setting of a middle income country, the thrombolysis incidence and outcomes were similar to those of other well-structured services. After 1 year, patients thrombolyzed in the 4.5-hour time window had a better outcome. More than proportions, rates provide additional information and could be used to benchmark services against others.

Key Words : Ischemic stroke, Thrombolysis, Population-based study, Incidence, Outcome, Middle income country, Epidemiology

Background

In many countries, stroke units and ischemic stroke (IS) thrombolysis have been changing the case fatality, the functional status and, in fact, have created a new paradigm of stroke care [1]. In Brazil, a country where stroke is the second most common cause of death, IS mortality has been decreasing over the last 3 decades [2]. In 2012 the Brazilian Health Ministry launched a National Stroke Policy Act encompassing new policies for hyperacute stroke care which should lead to additional improvement [3]. However, so far only scarce data have been available about the rate and efficacy of thrombolysis in Brazil.

Many reports present the proportion of patients admitted with IS who receive thrombolysis [4,5]. This gives some measure of activity and efficiency of prehospital and hospital triage. Some stroke centers have reported rates of thrombolysis as high as 20%, but without knowing which populations these services serve, these proportions do not indicate how well or equitably the treatment is being delivered [6]. The Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis for Stroke provided lysis rates (number treated per million population) for each participating country [7]. As far as we know, the first population data came from Lothian, Scotland, which reported a thrombolysis rate of 5.3 per 100,000 population in 2007-2008 [6].

In Brazil, by law, all citizens have free access to the National Health System whose organizational principles include universality and equity [8]; however, very few citizens have access to ideal stroke care [9,10]. In fact, in 2013, only 1.2% of all Brazilian hospitals had the infrastructure to receive hyperacute stroke patients (82 stroke centers/6,690 hospitals) [9,11]. Using population data from the Joinville Population-Based Stroke Registry [12], we aim to describe the trends of thrombolysis over 7 years. We ascertained proportions, incidence rates, thrombolysis times and symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage (sICH) proportions after thombolysis as well as case fatalities. We also compared the 12-month functional outcomes between thrombolyzed and nonthrombolyzed patients when 4.5 h became the new time window.

Methods

Study Population

In the 2010 Brazilian census, the Joinville population included 515,288 inhabitants in an area of 1,130 km2. The city has 2 stroke centers and 3 general hospitals, all with 24-hour computed tomography (CT) services, and 1 public institutional care facility, totaling 1,078 beds [13]. Since 2005, stroke patients have been treated by the national emergency medical service [Serviço de Atendimento Móvel de Urgência (SAMU)] [14], which uses a standard checklist based on the Cincinnati Stroke Scale [15].

Method and Collection Period Data

From the Joinville population-based stroke registry, we prospectively ascertained a cohort of all cases of IS, including first-ever and recurrent events, occurring from 2005 to 2007 and from 2009 to 2011. The Joinville Population-Based Stroke Registry is an ongoing stroke data bank initiated in 2005. The registry used the ideal methodology proposed by Sudlow and Warlow [16] as well as the Stroke-Steps modular program proposed by the WHO (first step for all hospital cases, second step for checking of death certificates and third step for the hot pursuit of mild events) [17]. In 2008, we could not ascertain the total number of IS which had occurred in Joinville, except the data of thrombolyzed patients. So, for this year, the number of IS was an average of the 2 years before and after 2008. The detailed methods of cohort recruitment have been described elsewhere [12]. In brief, using multiple overlapping sources, two study nurses registered, on a daily basis, all stroke subtype cases confirmed by a neurologist in all city emergency rooms. A brain CT scan was obtained following a concise clinical and neurological examination by a neurologist certified in NIHSS examination, and eligibility for thrombolytic treatment was individually determined based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Diagnostic Criteria and Outcome Measures

Intravenous thrombolysis was administered in accordance with an institutional protocol, which was based on the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) trial and the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study (ECASS) III trial [18,19]. The symptom time was ascertained by history, the door time as time of hospital arrival and the needle time as starting tPA bolus infusion. Patients who awoke with stroke symptoms were excluded from the symptom-to-door time calculation. To evaluate the extension of ischemic lesions in the intracranial CT scan, we used the ASPECTS (Alberta Stroke Program Early CT score) [20]. To measure functional dependency, we adopted the modified Rankin scale (mRS) [21] which ranges from 0 (no symptoms) to 6 (death). Patients with 0-2 were classified as independent and 3-5 as dependent. A favorable thrombolysis was considered when the outcome was an mRS of 0 or 1. The functional outcomes were measured during the first month (face to face) and at 12 months (by telephone) [12]; however, these data were available only for patients cared for after 2008 (rtPA 4.5-hour time window) [19]. To quantify clinical severity, we used four categories (0-8, 9-13, 14-22, >22) of the NIHSS scale as proposed by the Canadian Stroke Network [22]. To ascertain any intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), all who received rtPA must have had a second brain CT within 24 h after admission. During the hospital stay, if the patient had a clinical deterioration a third brain CT was done. For nonlysed cases a second brain CT was also done when necessary. All images and medical records were reviewed. As our analysis started in 2005, we considered an sICH when the patient had any neurological clinical worsening or NIH decline ≥4 and any cerebral hemorrhage in the control brain CT as proposed in ECASS II in the following 7 days [23,24]. A cutoff of 5 thrombolyses per 100,000 population for the thrombolysis rate was used as proposed by National Services Scotland (QIS standards 2009) [5,6,25] as well as the proportion of patients with door-to-needle time below or equal to 1 h.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All eligible cases of hyperacute IS of residents of Joinville above 18 years old were included. Patients above 80 years old were thrombolyzed according to the judgment of the stroke neurologist. From 2005 to 2008, patients who arrived within 3 h after symptoms had become apparent were eligible for tPA as published by the NINDS study [18]. After 2008, this time period was extended to 4.5 h after the publication of ECASS III [19]. In all periods, only patients with NIH above 3 points were thrombolyzed except when patients had language disturbances or isolated homonymous hemianopia (NIH 2-3) [19]. To compare the 12-month functional outcome (mRS) between thrombolyzed (n = 107) versus nonthrombolyzed patients (n = 544), we pooled the patients from 2009 to 2011 (4.5-hour time window). In this comparison, patients with recurrent stroke, NIH scale <4 and age <18 years were excluded in both groups.

Routine Investigation

After having obtained written informed consent from all patient or their relatives, biochemical, electrocardiographic and radiological tests in all patients were performed and the research nurses obtained information about demographics and risk factors. A neurologist was responsible for the NIH score, Bamford (Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project) and TOAST classification [18,26,27]. The routine of stroke thrombolysis and stroke investigation followed the guidelines proposed by the Brazilian Society of Cerebrovascular Diseases [28].

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the 95% confidence interval (CI) assuming a Poisson distribution for the number of events [29]. Incidence rates were calculated using national census for 2010 as denominators and intercensal data for the other years [30]. The incidence rates were age-adjusted to the Brazil population (2010) and the world SEGI population (2000) by the direct method [31]. Differences among patient subgroups were evaluated by using the χ2 test, the t test or the Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate. To identify the predictors of a favorable outcome (mRS 0-1) at 12 months, a multivariate logistic regression model was used. Baseline characteristics that showed an association with this outcome (p < 0.2) at univariate analysis were selected for the multivariate logistic model. The multivariate logistic model was adjusted for gender, age (grouped as 54 years or younger, 55-74 years and 75 years or older), NIH scale (assumed as 4 categories: 4-8 or mild, 9-13 or moderate, 14-22 or severe and >22 or coma), hypertension, diabetes, smoking, coronary heart disease, years of education, TOAST classification and lysis assignment. Statistical analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill., USA). The study was approved by the Ethics in Research Committees of all involved hospitals and universities. The reporting of this study conforms to the STROBE statement [32].

Results

We ascertained 3,552 IS from 2005 to 2011. Of those, 262 were thrombolyzed, but 31 patients moved to other cities and 11 were lost to follow-up, leaving 220 patients in the final sample. Table 1 shows a baseline overview of the sample. The mean age was 66.6 years (SD ±2.9), 50.4% were female, 15% (30/220) were more than 80 years old and 30.2% (63/220) were illiterate or had less than 4 years of education. Hypertension and diabetes were the most prevalent risk factors in 77 and 29% of the sample, respectively. On arrival at the emergency department, the median NIH was 14 (IQR 9-19), mainly at the moderate severity quartile [NIH 14-22; 36.7% (80/218)]. The mean glucose level was 7.7 mmol/l (SD ±0.5). On the Bamford classification, 41% (89/218) had total anterior circulation syndrome and on the TOAST classification, 30.9% had atherothrombotic IS. Table 2 shows that over 7 years the mean proportion of thrombolyzed patients was 6.2% (220/3,552; 95% CI, 5.4-7.0), but on a yearly basis it increased from 1% in 2005 (7/526; 95% CI, 0.5-2.7) to 11% in 2011 (60/537; 95% CI, 8.6-14.1; p < 0.0001). sICH ranged from 0% in 2005-2006, reached a peak of 11% in 2010 and fell to 2% in 2011. The overall mean proportion of sICH was 6% (14/220) and of those, 57% (8/14) died. The median symptom-to-door time was 71 min (IQR: 51-113), door-to-needle time was 79 min (IQR: 53-115) and symptom-to-needle time was 160 min (IQR: 117-210). The proportion of thrombolyzed patients within 1 h after arrival at hospital was 30.3% (50/165).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of thrombolyzed patients from 2005 to 2011 in Joinville, Brazil

| 2005 (n = 7) | 2006 (n = 18) | 2007 (n = 22) | 2008 (n = 54) | 2009 (n = 31) | 2010 (n = 37) | 2011 (n = 51) | All (n = 220) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | ||||||||

| Mean age ± SD, years | 65 ± 10.7 | 69.8 ± 13.8 | 63 ± 14.0 | 63.6 ± 12.5 | 68.5 ± 15.1 | 71.2 ± 13.1 | 65.1 ± 14.7 | 66.6 ± 2.9 |

| Females, % | 71.4 | 66.6 | 36.3 | 47.5 | 41.4 | 44.7 | 45.1 | 50.4 |

| Age >80 years, % | 0 | 22.2 | 4.5 | 1.9 | 17.3 | 40.5 | 15.7 | 14.6 |

| Years of education | ||||||||

| <4 years (illiterate) | 1 (16.7) | − | 1 (4.5) | 18 (35.3) | 13 (42) | 11 (32.4) | 19 (38.8) | 63 (30.2) |

| 4 years | 5 (83.3) | 6 (35.3) | 10 (45.5) | 17 (33.3) | 11 (35) | 17 (50) | 19 (38.8) | 83 (39.9) |

| 8 years | − | 9 (52.3) | 9 (40.9) | 9 (17.6) | 5 (16.1) | 1 (2.9) | 3 (6.1) | 36 (17.3) |

| 11 years | − | 2 (11.8) | 2 (9.1) | 7 (13.7) | 1 (3.2) | 5 (14.7) | 8 (16.3) | 25 (12) |

| >11 years | − | − | − | − | 1 (3.2) | − | − | 1 (0.5) |

| Unknown | − | 1 | − | 3 | − | 3 | 2 | 12 |

| Premorbid risk factor | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 6 (85.7) | 14 (77.7) | 12 (54.5) | 46 (85.2) | 21 (72.4) | 28 (75.6) | 41 (80.3) | 168 (77) |

| Diabetes | 1 (14.3) | 5 (27.7) | 4 (18.2) | 21 (38.9) | 6 (20.7) | 11 (28.9) | 14 (27.5) | 62 (28.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 (14.3) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (27.3) | 18 (33.4) | 5 (17.2) | 0 | 10 (19.6) | 44 (20.2) |

| Smoker (current) | 2 (28.6) | 5 (27.7) | 5 (22.7) | 5 (12.8) | 3 (10.3) | 5 (13.5) | 10 (19.6) | 35 (16.1) |

| Dyslipidemia | 2 (28.6) | 3 (16.6) | 8 (36.3) | 4 (7.4) | 5 (17.3) | 25 (67.5) | 9 (18) | 56 (25.7) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 2 (9.1) | 7 (12.9) | 2 (6.9) | 4 (10.8) | 3 (5.9) | 20 (9.2) |

| Clinical measures | ||||||||

| Admission NIHSS score | ||||||||

| 0 – 8 (mild) | 2 (28.6) | 1 (5.5) | 4 (18.2) | 7 (13.2) | 8 (28.6) | 6 (16.2) | 15 (28.3) | 43 (19.7) |

| 9 – 13 (moderate) | 1 (14.3) | 8 (44.4) | 7 (31.8) | 13 (24.5) | 3 (10.7) | 11 (29.7) | 21 (39.6) | 64 (29.4) |

| 14 – 22 (severe) | 4 (57.1) | 8 (44.4) | 9 (40.9) | 26 (49) | 3 (10.7) | 14 (37.8) | 16 (30.2) | 80 (36.7) |

| >22 (coma) | 0 | 1 (5.5) | 2 (9.1) | 7 (13) | 14 (50) | 6 (16.2) | 1 (1.8) | 31 (14.2) |

| Median (IQR) | 14 (11 – 18) | 15 (9 – 22) | 14 (8 – 17) | 15 (11 – 20) | 15 (9 – 20) | 14 (7 – 21) | 11 (9 – 15) | 14 (9 – 19) |

| Bamford classification | ||||||||

| LACS | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 2 (9.1) | 5 (9.3) | 3 (9.7) | 1 (2.7) | 3 (5.9) | 16 (7.3) |

| PACS | 1 (14.3) | 8 (44.4) | 8 (36.4) | 14 (25.9) | 14 (45.2) | 10 (27) | 35 (68.6) | 90 (40.9) |

| TACS | 6 (78.6) | 8 (44.4) | 11 (50) | 28 (51.9) | 12 (38.7) | 21 (56.8) | 11 (21.6) | 89 (40.5) |

| POCS | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 7 (13) | 2 (6.5) | 5 (13.6) | 2 (3.9) | 17 (7.7) |

| TOAST classification | ||||||||

| Lacunar | 0 | 2 (11.1) | 2 (9.1) | 2 (3.7) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (8.1) | 9 (17.6) | 20 (9.1) |

| Atherothrombotic | 3 (42.8) | 5 (27.7) | 5 (22.7) | 21 (38.9) | 5 (16.1) | 16 (43.2) | 13 (25.5) | 68 (30.9) |

| Cardioembolic | 3 (42.8) | 6 (33.3) | 7 (31.8) | 17 (31.5) | 11 (35.5) | 10 (27) | 20 (39.2) | 67 (30.5) |

| Undetermined | 1 (14.3) | 4 (22.2) | 7 (31.8) | 14 (26) | 16 (52) | 7 (18.9) | 3 (5.9) | 52 (23.6) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (5.5) | 1 (4.5) | 2 (3.7) | − | 1 (2.7) | 6 (11.8) | 11 (5.0) |

| Mean admission glucose ± | ||||||||

| SD, mmol/1 | 8.2 ± 2.2 | 7.3 ± 2.6 | 7.2 ± 1.9 | 8.1 ± 3.1 | 7.1 ± 2.4 | 7.9 ± 4.2 | 8.1 ± 2.4 | 7.7 ± 0.5 |

Data are number (%), unless otherwise indicated. The Bamford classification is the clinical classification of the IS subtype, and the TOAST classification is the mechanism of disease for IS subtypes. n = Number of patients lysed; LACS = lacunar syndrome; PACS = partial anterior circulation syndrome; TACS = total anterior circulation syndrome; POCS = posterior circulation syndrome.

Table 2.

Thrombolysis proportions, sICH, thrombolysis times and 30-day case fatality from 2005 to 2011 in Joinville, Brazil

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS, n | 526 | 469 | 402 | 498a | 524 | 596 | 537 | 3,552 |

| IS lysed, n | 7 | 18 | 22 | 54 | 31 | 37 | 51 | 220 |

| IS lysed (95% CI), % | 1.3 (0.5 – 2.7) | 3.8 (2.3 – 6.6) | 5.5 (3.5 – 8.2) | 10.8 (8.3 – 13.9) | 5.9 (4.1 – 8.3) | 6.1 (4.2 – 8.5) | 11.2 (8.6 – 14.2) | 6.2 (5.4 – 7.0) |

| 7-day ICH after lysis, % (n) | 0 | 0 | 9.1 (2/22) | 9.3 (5/54) | 6.5 (2/31) | 10.8 (4/37) | 1.7 (1/60) | 6.4 (14/220) |

| Death with sICH, % (n) | 0 | 100 (1/1) | 50 (1/2) | 40 (2/5) | 100 (2/2) | 25 (1/4) | 100 (1/1) | 57 (8/14) |

| Median thrombolysis time (IQR), min | ||||||||

| Symptom-to-door | 86 (33 – 129) | 101 (66 – 118) | 60 (37 – 96) | 117 (97 – 131) | 96 (71 – 122) | 60 (38 – 85) | 91 (60 – 128) | 71 (51 – 113) |

| Door-to-needle | 67 (54– 127) | 50 (27 – 69) | 64 (50 – 112) | 83 (68 – 108) | 74 (59 – 89) | 83 (68 – 108) | 80 (54 – 120) | 79 (53 – 115) |

| Lysed within 1 h after | ||||||||

| hospital arrivala, % (n) | 28.6 (2/7) | 16.6 (3/18) | 30.9 (9/22) | 45 (19/42) | 24 (7/29) | 15.6 (5/32) | 33.4 (5/15) | 30.3 (50/165) |

| 30-day case fatality, % (n) | 29 (2/7) | 28 (5/18) | 14 (3/22) | 31 (17/54) | 42 (13/31) | 32 (12/37) | 32 (16/51) | 29 (64/220) |

Data available in 75% (165/220).

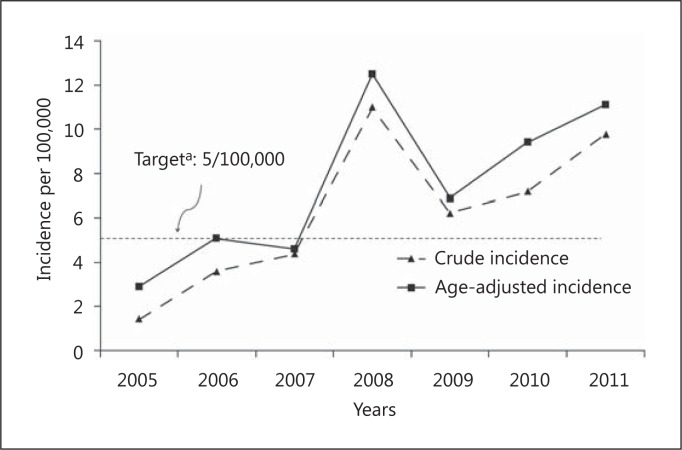

Figure 1 shows the evolution of crude incidence trends of IS age-adjusted to the world population which had been thombolyzed over 7 years. The crude incidence increased 7-fold between 2005 and 2011, ranging from 1 (95% CI, 0.6-3) per 100,000 population in 2005 to 10 (7-13) per 100,000 population in 2011 above the equity cutoff proposed by the National Services Scotland (UK) [6,28]. The overall crude mean incidence was 6 (5-7) per 100,000 population (220/3,513,703).

Fig. 1.

Age-adjusted IS thrombolysis incidence in Joinville, Brazil, 2005-2011: a 7-year population-based study.

We compared the 1-year functional status (mRS) between patients who were thrombolyzed and nonthrombolyzed in the 2009-2011 period (4.5-hour time window). In both groups only first-ever strokes and NIH ≥4 were included. We identified 544 patients in the nonthrombolyzed group and 107 patients in the thrombolyzed group. In this group, 4 patients with NIH <3 were excluded from the analysis (3 had aphasia and 1 vertebrobasilar symptoms). The median NIH was not different between the groups; however, the NIH categories were not homogenous, with more patients with NIH 4-8 and >22 in the nonthrombolyzed group. This group also had more hypertension and diabetes and a lower level of education (table 3). After 12 months, there were more independent patients in the thrombolyzed group [mRS 0-1; 36% (38/107)] than in the nonthrombolyzed group [mRS 0-1; 24% (131/544); p = 0.016] as well as less dependent patients [mRS 3-5; 15% (16/107) vs. 24% (132/544); p = 0.04].

Table 3.

Functional outcome after 12 months between first-ever IS thrombolyzed in 4.5 h and not throm-bolyzed in Joinville, 2009 – 2011

| No lysis (n = 544) | Lysis (n = 107) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

|

69.3 ± 14.0 | 68.8± 13.3 | 0.608 |

|

290 (53.3) | 50 (46.7) | 0.244 |

|

|||

|

87 (16.0) | 14 (13.1) | 0.460 |

|

240 (44.1) | 54 (50.5) | |

|

217 (39.9) | 39 (36.4) | |

| NIH scale | |||

|

12 (7 – 22) | 12 (9 – 20) | 0.731 |

|

<0.001 | ||

|

194 (35.7) | 25 (23.4) | |

|

109 (20.0) | 32 (29.9) | |

|

108 (19.9) | 37 (34.6) | |

|

133 (24.4) | 13 (12.1) | |

| CV risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 441 (81.1)a | 73 (68.2)b | 0.012 |

| Diabetes | 199 (36.6)c | 25 (23.4) | 0.027 |

| Smoking | 105 (19.3) | 16 (15.0) | 0.409 |

| yocardial infarction | 62 (11.4)d | 11 (10.3)e | 0.878 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 77 (14.2)f | 17 (15.9)g | 0.134 |

| TOAST classification | 0.033 | ||

| Atherothrombotic | 122 (22.4) | 23 (21.5)h | |

| Lacunar | 70 (12.9) | 9 (8.4) | |

| Cardioembolic | 199 (36.6) | 39 (36.4) | |

| Undetermined | 101 (18.6) | 22 (20.6) | |

| Other | 52 (9.6) | 12 (11.2) | |

| Bamford classification | 0.064 | ||

| LACS | 78 (14.3)i | 7 (6.5) | |

| PACS | 239 (43.9) | 56 (52.3) | |

| TACS | 188 (34.6) | 41 (38.3) | |

| POCS | 32 (5.9) | 3 (2.8) | |

| Years of education | <0.001 | ||

| Unknown | 7 (1.3) | 15 (14.0) | |

| Illiterate (<4 years) | 223 (41.0) | 33 (30.8) | |

| 4 years | 212 (39.0) | 41 (38.3) | |

| 8 years | 39 (7.2) | 6 (5.6) | |

| 11 years | 46 (8.5) | 11 (10.3) | |

| >11 years | 17 (3.1) | 1 (0.9) | |

| mRS at 12 months | 0.116 | ||

| 0 | 41 (7.5) | 13 (12.1) | |

| 1 | 90 (16.5) | 25 (23.4) | |

| 2 | 41 (7.5) | 4 (3.7) | |

| 3 | 48 (8.8) | 7 (6.5) | |

| 4 | 65 (11.9) | 7 (6.5) | |

| 5 | 19 (3.5) | 2 (1.8) | |

| 6 | 240 (44.1) | 49 (45.8) | |

| 0 – 1 | 131 (24.1) | 38 (35.5) | 0.016 |

| 0 – 2 | 172 (31.6) | 42 (39.3) | 0.143 |

| 3 – 5 | 132 (24.3) | 16 (15.0) | 0.043 |

| 3 – 6 | 372 (68.4) | 65 (60.7) | 0.143 |

Data are number (%), unless otherwise indicated. CV = Cardiovascular; LACS = lacunar syndrome; PACS = partial anterior circulation syndrome; TACS = total anterior circulation syndrome; POCS = posterior circulation syndrome. Unavailable: hypertension 3 cases

1 case

diabetes 1 case

myocardial infarction 19 cases

3 cases

atrial fibrillation 29 cases

1 case

TOAST 2 cases

Bamford 7 cases.

The univariate analysis for the outcome mRS 0-1 at 12 months showed significant differences for age, gender NIH scale, presence of hypertension, diagnosis of diabetes, smoking status, atrial fibrillation, years of education, TOAST classification and lysis assignment (online suppl. table S1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000356984). Previous coronary heart disease was included in the logistic model, once it showed p = 0.158. After correcting for the baseline variables, lysis was strongly associated with a better 12-month outcome, as were also age, NIH and the presence of diabetes. When only those variables were included in a regression model, thrombolysis was associated with an additional 113% chance for a favorable outcome (HR 2.13; 95% CI, 1.23 – 3.67; online suppl. table S2).

Discussion

We showed, in a population-base setting of a middle income country, a progressive increase lysis rate over 7 years, and also thrombolysis times and a proportion of symptomatic ICH. Furthermore, we showed that lysis for stroke patients was associated with a significant better functional outcome after 12 months of follow-up. The Joinville Stroke Registry is an ongoing population-based data bank initiated in 1995, which allows us to calculate our incidence rate and compare it with other populations [12].

Our study has some limitations: in 2008, in the Joinville Stroke Register only lysis data were available. So, for this year the number of IS was an average of the number of IS in 2006-2007 plus 2009-2010. The functional assessment was obtained by telephone. Some argue that the reliability of this method is low and cannot be recommended [33]. However, a trained nurse was in charge of all the phone contacts, which was most probably a nondifferential information bias. The main strengths of our study are to show the effectiveness of IS thrombolysis in a medium-sized city of a middle income country and to report the number of IS thrombolysis by rates, which can allow better planning of public policies [6].

sICH is the most feared complication after thrombolysis. It ranged considerably between studies which may be related to the differences in the criteria used to define sICH [32]. In the small numbers of our cohort, it ranged from 0% in 2005 to 11% in 2010 and the overall proportion was 6.4% (14/220). In a critical review of 7 randomized clinical trials (2,124 patients), 7 stroke registries (15,054 patients) and 10 cohort studies (4,455 patients), the overall mean sICH was 5.6% (SD 2.3) [35]. In studies that also used the ECASS II criteria, such as the SITS-MOST (Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study) registry and a cohort study by Strbian et al. [35], the proportion of SIH was 4.6 and 7%, respectively [36].

After 1 year, 36% (95% CI, 27-46) of all patients had a favorable outcome (mRS 0-1). This result was similar to patients lysed in 4.5 h in the last report from SITS-ISTR (Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-International Stroke Thrombolysis Register) where 39% (95% CI, 30-49; 42/107) were functionally independent (mRS 0-1) after 3 months [36]. However, our sample is population-based and the SITS registry includes a broad range of hospitals. Nevertheless, our results were the same as reported in a population study conducted in 2007-2008 among 18 primary care hospitals of the canton of Bern [37]. In this study, 107 patients thrombolyzed within 4.5 h were compared with 700 without thrombolysis. The mRS was also assessed by telephone. After 1 year, 45% (40-49) were independent (mRS 0-2) [37], a result that overlaps with the confidence intervals in our sample.

In our study, only 30.3% (50/165) were thrombolyzed within 1 h after arrival at hospital, which is far from the proposed ideal of an 80% cutoff [38]. However, according to recent data from the Get With the Guidelines-Stroke Program, of the acute IS patients treated with tPA within 3 h of symptom onset, fewer than one third had door-to-needle times of ≤60 min [38]. Our thrombolysis times, which did not change after extension of the tPA time to 4.5 h, were similar to two other national cohorts [39,40] as well as the last SITS-ISTR [36].

Hospital-based series have shown that thrombolysis rates in IS patients vary between 5.7 and 21.7% [6,36]. Scarce incidence data are available in the literature, and reporting the number of patients treated per 100,000 population provides additional information that can be used to benchmark services against others [5,6,37]. For example, in 2011, according to the stroke services in Scotland, UK (a population of 5,222,100), 644 of 8,187 IS were thrombolyzed. This means a proportion of 8% and an incidence of 12 per 100,000 population [25]. In a centralized model in the north of the Netherlands, 4 hospitals had a single stroke center for rtPA treatment, reaching a lysis proportion of 22% (95% CI, 17-27). With a population under care of 577,081, their lysis incidence was 11 per 100,000 (95% CI, 8-14 per 100,000) [37]. Online supplementary table S3 displays the incidence and proportion of lysis in the different centers. One third of our sample had <4 years of formal education or was illiterate. Only 1 patient had a college education. This finding confirms our previous impression that the first-ever incidence in Joinville is inversely proportional to the educational level. The stroke incidence was inversely correlated with years of education (r = −0.532; p < 0.001) [41]. Despite these data, the lysis rate increased over the years. It is possible that campaigns to increase stroke awareness, such as World Stroke Day [9], regular lectures to the local emergency medical service [Serviço de Atendimento Móvel de Urgência (SAMU)] [14] and the continuous education program (4 times per month since 2006) for patients and relatives at the stroke unit also might raise the public awareness.

In conclusion, cohort studies, randomized clinical trials and stroke registries have reported IS thrombolysis outcomes; however, scarce data are available from population-based studies. In the population of a Brazilian city, we reported a 7-year learning curve of hyperacute stroke care. In fact, as only 1.2% of Brazilian hospitals have rtPA in their emergency units, the challenge of ideal acute stroke care in Brazil is huge. The main thrombolysis indicators such as lysis proportions, sICH, 30-day case fatality and functional outcome were similar to other registries and cohorts around the world. Moreover, we also have shown the effectiveness of thrombolysis on a long-term basis. Finally, in our opinion the thrombolysis incidence seems to be a better way of benchmarking services, especially for planners, providing better equity care.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary methods

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysis, n | 7 | 18 | 22 | 54 | 31 | 37 | 51 |

| Population, n | 487,047 | 496,050 | 504,893 | 492,101 | 497,329 | 515,288 | 520,905 |

| Crude | 1.4 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 11.0 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 9.8 |

| incidence | (0.6 – 2.9) | (2.2 – 5.7) | (2.7 – 6.6) | (8.3 – 14.4) | (4.2 – 8.8) | (5.1 – 9.9) | (7.3 – 12.9) |

| Age-adjusted | 2.9 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 12.5 | 6.9 | 9.4 | 11.0 |

| incidenceb | (1.2 – 6.0) | (3.0 – 8.1) | (2.9 – 7.0) | (9.4 – 16.3) | (4.7 – 9.8) | (6.6 – 13.0) | (8.2 – 12.9) |

Values in parentheses represent 95% CI.

aTarget in Scottish Stroke Audit 2012 [25].

bAge-adjusted to the world population of 2010 (SEGI).

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to Martin Dennis, Edinburgh University, UK and Daniel C. Bezerra, FIOCRUZ, Brazil who did a critical review of the manuscript. This work was supported by the University of Joinville Region, Clinica Neurológica de Joinville and Joinville Health Secretary.

References

- 1.Langhorne P, Cadilhac D, Feigin V, Grieve R, Liu M. How should stroke services be organised? Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:62–68. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00011-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lotufo PA, Goulart AC, Fernandes TG, Benseñor IM. A reappraisal of stroke mortality trends in Brazil (1979-2009) Intern J Stroke. 2013;8:155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministério da Saúde Protocolos clínicos e diretrizes terapêuticas. http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/arquivos/pdf/pcdt_trombolise_avc_isq_agudo.pdf (accessed July 14, 2012).

- 4.Schumacher HC, Bateman BT, Boden-Albala B, Berman MF, Mohr JP, Sacco RL, Pile-Spellman J. Use of thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: analysis of the nationwide inpatient sample 1999 to 2004. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;50:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lahr MM, Luijckx GJ, Vroomen PC, van der Zee DJ, Buskens E. Proportion of patients treated with thrombolysis in a centralized versus a decentralized acute stroke care setting. Stroke. 2012;43:1336–1340. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.641795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kerr E, Dennis M, Keir S. Thrombolysis: attempting to reduce postcode prescribing in Scotland? Int J Stroke. 2010;5:486–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wahlgren N, Ahmed N, Dávalos A, SITS-MOST investigators Thrombolysis with alteplase for acute ischaemic stroke in the Safe Implementation of Thrombolysis in Stroke-Monitoring Study (SITS-MOST): an observational study. Lancet. 2007;369:275–282. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Azevedo e Silva G, Menezes AM, Monteiro CA, Barreto SM, Chor D, Menezes PR. Chronic non-communicable diseases in Brazil: burden and current challenges. Lancet. 2011;377:1949–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martins SC, Pontes-Neto OM, Alves CV, de Freitas GR, Filho JO, Tosta ED, Cabral NL, Brazilian Stroke Network Past, present, and future of stroke in middle-income countries: the Brazilian experience. Int J Stroke 2013, E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Rolim CLRC, Martins M. Qualidade do cuidado ao acidente vascular cerebral isquêmico no SUS. Cad Saúde Pública. 2011;27:2106–2116. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2011001100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federação Brasileira de Hospitais. http://fbh.com.br/2011/06/06/hospitais-no-pais/ (accessed August 2013).

- 12.Cabral NL, Gonçalves A, Longo A, Moro C, Costa G, Amaral C, et al. Trends in stroke incidence, mortality and case-fatality rates in Joinville, Brazil: 1995-2006. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:749–754. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.164475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE), 2010. http://www.ibge.gov.br/cidadesat/topwindow.htm?1 (accessed September 2012).

- 14.Ministério da Saúde, Portal da Saúde. http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/saude/visualizar_texto.cfm?idtxt=30273&janela=1 (accessed May 2013).

- 15.Kothari RU, Pancioli A, Liu T, Brott T, Broderick J. Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale: reproducibility and validity. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:373–378. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(99)70299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Comparing stroke incidence worldwide: what makes studies comparable? Stroke. 1996;27:550–558. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The WHO STEPwise Approach to Stroke Surveillance. Overview and Manual (Version 2.0). Noncommunicable Diseases and Mental Health. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/entity/ncd_surveillance/steps/en (accessed December 7, 2013).

- 18.The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Dávalos A, Guidetti D, et al. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barber PA, Demchuk AM, Zhang J, Buchan AM, ASPECTS Study Group Validity and reliability of a quantitative computed tomography score in predicting outcome in hyperacute stroke before thrombolytic therapy. Lancet. 2000;355:1670–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02237-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sulter G, Steen C, De Keyser J. Use of the Barthel index and modified Rankin scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 1999;30:1538–1541. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.8.1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saposnik G, Fang J, Kapral MK, Tu JV, Mamdani M, Austin P, Johnston SC, Investigators of the Registry of the Canadian Stroke Network (RCSN) and the Stroke Outcomes Research Canada (SORCan) Working Group The iScore predicts effectiveness of thrombolytic therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:1315–1322. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.646265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berger C, Fiorelli M, Steiner T, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic brain tissue. Asymptomatic or symptomatic? Stroke. 2001;32:1330–1335. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hacke W, Kaste M, Fieschi C, von Kummer R, Dávalos A, Meier D, Larrue V, Bluhmki E, Davis S, Donnan G, Schneider D, Diez-Tejedor E, Trouillas P. Randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial of thrombolytic therapy with intravenous alteplase in acute ischaemic stroke (ECASS II). Second European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study Investigators. Lancet. 1998;352:1245–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)08020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scottish Stroke Audit 2012 Annual Report. http://www.strokeaudit.scot.nhs.uk/Downloads/2012_report/SSCA-annual-report-2012-web.pdf (accessed May 9, 2013).

- 26.Adams HP, Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Love BB, Gordon DL, Marsh EE, III, TOAST Investigators Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. Stroke. 1993;24:35–41. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bamford P, Sandercock M, Dennis J, Burn C, Warlow CP. Classification and natural history of clinically identifiable subtypes of cerebral infarction. Lancet. 1991;337:1521–1526. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93206-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sociedade Brasileira de Doenças Cerebrovasculares (SBDCV) Primeiro Consenso Brasileiro para trombólise no acidente vascular cerebral isquêmico agudo. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2002;60:675–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keyfitz N. Sampling variance of standardized mortality rates. Hum Biol. 1966;38:309–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DATASUS, Ministerio da Saúde. http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?ibge/cnv/popsc.def (accessed August 2012).

- 31.Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Murray CJL, Lozano R, Inogue M.Age standardisation of rates: a new WHO world standard. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/paper31.pdf (accessed August 2012).

- 32.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasner SE. Clinical interpretation and use of stroke scales. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:603–612. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70495-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Seet RCS, Rabinstein AA. Symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage following intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: a critical review of case definitions. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:106–114. doi: 10.1159/000339675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strbian D, Sairanen T, Meretoja A, Pitkaniemi J, Putaala J, Salonen O, et al. Patient outcomes from symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after stroke thrombolysis. Neurology. 2011;77:341–348. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182267b8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahmed N, Wahlgren N, Grond M, Hennerici M, Lees KR, Mikulik R, Parsons M, Roine RO, Toni D, Ringleb P, SITS investigators Implementation and outcome of thrombolysis with alteplase 3-4.5 h after an acute stroke: an updated analysis from SITS-ISTR. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:866–874. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70165-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer U, Mono M-L, Zwahlen M, et al. Impact of thrombolysis on stroke outcome at 12 months in a population: the Bern stroke project. Stroke. 2012;43:1039–1045. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.630384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Saver JL. Timeliness of tissue-type plasminogen activator therapy in acute ischemic stroke: patient characteristics, hospital factors, and outcomes associated with door-to-needle times within 60 minutes. Circulation. 2011;123:750–758. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.974675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lange MC, Zétola VF, Parolin MF, Zamproni LN, Fernandes AF, Piovesan EJ, Nóvak EM, Werneck LC. Curitiba acute ischemic stroke protocol: a university hospital and EMS initiative in a large Brazilian city. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2011;69:441–445. doi: 10.1590/s0004-282x2011000400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cougo-Pinto PT, Santos BL, Dias FA, Fabio SRC, Werneck IV, Camilo MR, Abud DG, Leite JP, Pontes-Neto OM. Frequency and predictors of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage after intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke in a Brazilian public hospital. Clinics. 2012;67:739–743. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(07)06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cabral NL, Longo AL, Moro C, Ferst P, Oliveira FA, Vieira CV, Eluf-Neto J, Fonseca LAM, Gonçalves ARR. Education level explains differences in stroke incidence among city districts in Joinville, Brazil: a three-year population-based study. Neuroepidemiology. 2011;36:258–264. doi: 10.1159/000328865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary methods