Abstract

Background: People with chronic heart failure (HF) suffer from numerous symptoms that worsen quality of life. The CASA (Collaborative Care to Alleviate Symptoms and Adjust to Illness) intervention was designed to improve symptoms and quality of life by integrating palliative and psychosocial care into chronic care.

Objective: Our aim was to determine the feasibility and acceptability of CASA and identify necessary improvements.

Methods: We conducted a prospective mixed-methods pilot trial. The CASA intervention included (1) nurse phone visits involving structured symptom assessments and guidelines to alleviate breathlessness, fatigue, pain, or depression; (2) structured phone counseling targeting adjustment to illness and depression if present; and (3) weekly team meetings with a palliative care specialist, cardiologist, and primary care physician focused on medical recommendations to primary care providers (PCPs, physician or nurse practioners) to improve symptoms. Study subjects were outpatients with chronic HF from a Veteran's Affairs hospital (n=15) and a university hospital (n=2). Measurements included feasibility (cohort retention rate, medical recommendation implementation rate, missing data, quality of care) and acceptability (an end-of-study semi-structured participant interview).

Results: Participants were male with a median age of 63 years. One withdrew early and there were <5% missing data. Overall, 85% of 87 collaborative care team medical recommendations were implemented. All participants who screened positive for depression were either treated for depression or thought to not have a depressive disorder. In the qualitative interviews, patients reported a positive experience and provided several constructive critiques.

Conclusions: The CASA intervention was feasible based on participant enrollment, cohort retention, implementation of medical recommendations, minimal missing data, and acceptability. Several intervention changes were made based on participant feedback.

Introduction

Chronic heart failure (HF) is a leading cause of death, hospitalizations, health care costs, and disability in the United States, yet palliative care is poorly integrated into HF care.1 People with HF suffer from numerous symptoms, such as breathlessness, fatigue, and pain that worsen quality of life.2,3 These symptoms tend to persist despite optimal guideline-based HF management, and a symptom-oriented approach offered by palliative care may be beneficial. Despite many persuasive calls for palliative care in HF,4–6 HF patients are generally not seen by palliative care specialists in the outpatient setting, and the number of palliative care specialists is limited. Additional evidence is needed to guide how the palliative care needs in HF should be addressed and how palliative goals and expertise can be integrated into the care of patients with HF.

We previously found that HF patients and their informal caregivers desire support adjusting to illness, relief of symptoms, and a team approach to provide care early in the course of illness.7 Ideally, this care would be integrated into the ongoing chronic care of HF patients. To accomplish this, we developed a new intervention, Collaborative Care to Alleviate Symptoms and Adjust to Illness (CASA), with the ultimate goal of improving symptoms and quality of life in patients with HF. The CASA intervention was developed based on (1) evidence showing potentially modifiable contributors to quality of life2; (2) patient and informal caregiver major concerns and needs and preferences for palliative care7; and (3) a successful model of health care delivery: collaborative care. Symptoms and depression, or difficulty adjusting to illness, are important, potentially modifiable contributors to quality of life. Depression also increases the intensity of other symptoms.8 The conceptual framework for the CASA intervention is based on this evidence and elements of the theory of unpleasant symptoms9 integrated into an adaptation of the Wilson and Cleary model of health-related quality of life.10

The CASA intervention uses a collaborative care model, a successful care delivery model that improves depression (more than 40 randomized, controlled trials),11 with a recent study showing improvement in blood pressure, hemoglobin A1C, and lipids.12 The model offers advantages, including cost-effectiveness, leveraging allied health professionals such as nurses and social workers to assess and coordinate management of specific problems, and consultation with specialists who provide caseload supervision, particularly with patients who are not improving as expected. We conducted a pilot study to determine the feasibility and acceptability of CASA, which adapts this model of care to integrate palliative care into chronic care.

Methods

Design

We used a prospective clinical trial design with quantitative and qualitative methods to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of CASA. Patients were randomly allocated to CASA or a psychospiritual intervention that was also being pilot tested. Only patients allocated to the CASA intervention are described here. All patients provided informed written consent and the study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Subjects

Patients were recruited from outpatient clinics and inpatient hospital medical units at the Denver VA Medical Center from November 2011 to May 2012. University of Colorado Hospital recruitment was added near the end of the study period to examine feasibility in a different health system. Patients were eligible to participate if they had a diagnosis of HF, were 18 years of age or older, were able to read and speak English, had consistent telephone access, had a primary care provider (PCP), and met at least one additional criterion: (1) a hospitalization primarily for HF in the year prior; (2) taking at least 80 mg oral furosemide (or equivalent) daily in a single or divided dose for at least 2 weeks; (3) B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP)≥250 or amino-terminal pro BNP (NT-pro BNP) ≥1000; (4) creatinine clearance <60 mg/dL; or (5) Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ, a HF-specific health status measure) score ≤60.13 Patients were excluded from the study for any of the following: (1) previous diagnosis of dementia; (2) active substance abuse or dependence, as defined by a diagnosis in the medical record, an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Consumption (AUDIT-C) score ≥8,14 or at least one positive response on a two-item conjoint screen for substance abuse, “In the last year, have you ever drank or used drugs more than you meant to?” or “Have you felt you wanted or need to cut down on your drinking or drug use in the last year?”15; (3) metastatic cancer; (4) nursing home resident; or (5) bipolar affective disorder or schizophrenia.

Procedures

The PCPs of eligible patients were asked to approve their patients' enrollment in the study. If patients did not have PCPs, approval was obtained from their cardiologist. Participants were randomly allocated to the intervention arm after completion of baseline measures. Self-report measures assessed symptom severity (Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale-Revised),16,17 symptom distress and ability to manage symptoms (General Symptom Distress Scale, GSDS),18 heart failure specific quality of life (KCCQ),13 spiritual well-being (Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual),19 overall quality of life (Quality of Life At the End of Life),20 depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-9, PHQ-9),21 and anxiety symptoms (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7).22 After the 3-month period, participants completed the same survey measures again and participated in a qualitative interview.

CASA intervention

Symptom management

A registered nurse provided evidence-based, algorithm-guided management of breathlessness,23–25 fatigue,23,26 pain,27 and depression.28 Study nurses attended two half-day trainings with DB, a palliative care specialist, to learn and practice the symptom management algorithms and helping communication techniques. At an initial in-person visit, the nurses reviewed the baseline symptom measures with patients and they jointly decided on a primary symptom to target. Nurses presented assessment information at the collaborative care team meeting so that the team could consider recommendations for testing or treatment. Six to eight nurse visits primarily by phone, each occurring every 1 to 2 weeks were planned to reassess the target symptom and evaluate other symptoms using a structured symptom survey and to communicate team recommendations to the participants.

Psychosocial care

A psychologist or social worker provided participants with six structured telephone counseling visits, one every other week. The psychologist and social worker attended one and a half days of training and participated in biweekly supervision with Dr. Carolyn Turvey, the clinical psychologist who originally developed the psychosocial intervention. The counseling protocol was fully manualized and designed to help patients with chronic illness, particularly HF or chronic lung disease, adjust to living with illness and to alleviate depressive symptoms if present.29 After an initial in-person visit, four modules were covered by phone: grief and loss, role transition, behavioral activation (“getting active”), and pacing (balancing activity and rest). An additional pilot module called “Where am I going?” sought participants' reactions to different stages of adjustment to illness.7

Collaborative care

The nurse and the social worker or psychologist met weekly with a PCP, cardiologist, and palliative care specialist to discuss care changes to improve symptoms, guided by the symptom algorithms. Collaborative care team recommendations were entered into a progress note in the electronic medical record for review and co-signature by the patients' PCP. Unsigned orders were placed for PCPs to review and sign at their discretion. This methodology was successfully used in a study of collaborative care for patients with angina.30

Feasibility and acceptability outcome measurement

Feasibility

Feasibility was assessed by measuring (1) trial enrollment and retention rates; (2) whether the nurse and social worker/psychologist made the protocol-specified number, duration, and type (phone or in-person) visits; (3) percent of medical recommendations made by the collaborative care team implemented by PCPs; (4) missing data on self-report measures; (5) whether the CASA intervention addressed symptoms that participants ranked as “most bothersome” on the self-report symptom measures; and (6) whether basic quality of care was provided for depression, including assessment/management of positive screens for depression, potential suicidal thoughts, and target symptoms rated ≥7 in severity.

Acceptability

To assess acceptability, participants were interviewed after completion of the study by a qualitative researcher who was not a member of the intervention team. Digitally recorded interviews took place in person or by telephone and ranged from 35 to 105 minutes. Patients were asked their opinions about the intervention, such as what was helpful and not helpful, and their advice for changes. We asked for specific feedback on the following: timing and number of phone sessions, psychosocial care topics, expectations about the intervention, and how the intervention affected quality of life.

Data analysis

Enrollment, retention, and medical recommendation implementation rates were calculated. Pre-planned assessments of quality of care included determining whether depression, suicidality, and severe symptoms (≥7/10 in severity) were assessed and treated. We examined whether the symptoms targeted by the intervention were rated as “most bothersome” by participants on baseline measures. The percent missing data from baseline and follow-up self-report measures was calculated. As the study objective was to evaluate the feasibility and not the effect of the intervention, change scores and tests for significance were not done. Quantitative analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Qualitative analysis involved an iterative team-based process beginning with transcribing the interview data in spreadsheet format. One team member (CN) served as primary coder, with a sample of interviews also coded by another member (DB) until consensus was reached. A third team member (DM) also reviewed interview data and served as mediator of the team-based consensus process. A priori codes centered on the domains of the interview guide; subsequent codes emerged as the team discussed themes and concepts, confirming and disconfirming cases, and reached consensus on patterns and key findings. Once key findings were agreed upon, we conducted a participant member check to confirm validity.

Results

Feasibility

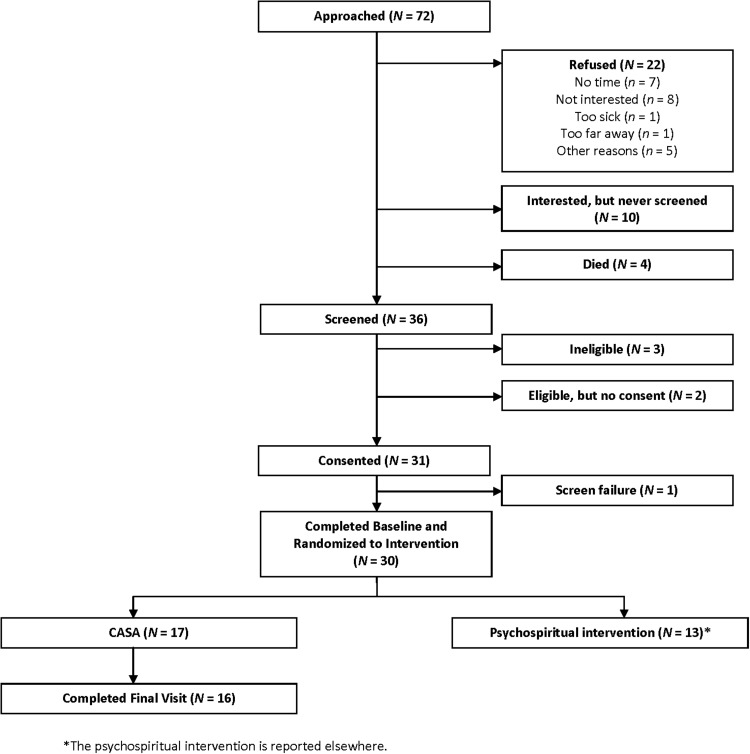

Of 72 patients approached, 30 were randomized for a participation rate of 42% (Fig. 1). Of the 17 participants randomized to the CASA intervention, one dropped out prior to the final visit saying he was too busy to participate, for a completion rate of 94%. All participants were male and the majority were white, with diversity in New York Heart Association class and etiology of HF (Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Study enrollment.

Table 1.

Collaborative Care to Alleviate Symptoms and Adjust to Illness (CASA) Participant Characteristics (n=17)

| Characteristic | N (%) or median [IQR] |

|---|---|

| Age | 63 [58–71] |

| Male | 17 (100%) |

| Ethnicity, white | 10 (58.8%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 8 (47.1%) |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 6 (35.4%) |

| Other | 3 (17.7%) |

| Education | |

| High school or GED | 2 (11.8%) |

| Some college | 11 (64.7%) |

| College graduate or postgraduate education | 3 (17.7%) |

| Unknown | 1 (5.9%) |

| NYHA class | |

| I | 2 (11.8%) |

| II | 8 (47.1%) |

| III | 6 (35.3%) |

| IV | 1 (5.9%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Diabetes | 6 (35.3%) |

| Hypertension | 12 (70.6%) |

| COPD | 4 (23.5%) |

| Sleep apnea | 5 (29.4%) |

| History of depression | 3 (17.7%) |

| History of alcohol abuse | 4 (23.5%) |

| History of other substance abuse | 3 (17.7%) |

| Etiology of heart failure | |

| Ischemic | 6 (35.3%) |

| Hypertension | 3 (17.7%) |

| Alcohol induced | 2 (11.8%) |

| Unknown | 6 (35.3%) |

| Medications | |

| Beta blocker | 12 (70.6%) |

| ACE or ARB | 10 (58.8%) |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 8 (47.1%) |

| Loop diuretic | 11 (64.7%) |

| Vasodilators | 4 (23.5%) |

| Digoxin | 6 (35.3%) |

| Antidepressants | 7 (41.2%) |

| Opiates | 5 (29.4%) |

| Nonopioid analgesic | 4 (23.5%) |

| Neuropathic pain medications | 4 (25.5%) |

ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

On average, the nurse made just under eight 30-minute visits with patient participants, 80% of which were by phone (Table 2). Around half of participants chose pain as the target symptom, and the other half chose fatigue or breathlessness. There was an average of between four and five 28-minute psychosocial visits per patient, 79% of which were by phone.

Table 2.

Intervention Process

| Process | Mean (SD) | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Nurse visits | ||

| Visits per patient | 7.88 (3.5) | |

| Time per visit (minutes) | 27.7 (21.2) | |

| Target symptom | ||

| Pain | 9 (53.0%) | |

| Fatigue or breathlessnessa | 8 (47.0%) | |

| Psychosocial care | ||

| Visits per patient | 4.4 (1.70) | |

| Time per visit (minutes) | 27.9 (10.8) | |

| Recommendations | N (%) recommended | N (%) completed |

| Add, change, or discontinue medication | 44 (50.6%) | 40 (90.9%) |

| Order test (e.g., imaging, ECG, pulmonary function tests) or lab (e.g., metabolic panel, TSH, testosterone) | 22 (25.3%) | 17 (77.3%) |

| Consult another service (physical or occupational therapy, mental health, nutrition) | 21 (24.1%) | 17 (81.0%) |

| Overall | 87 (100%) | 74 (85.1%) |

| Reasons recommendations were not completed | ||

| Study ended prior to getting consult/test (e.g., still on waitlist for physical therapy) | 6 (46.2%) | |

| Patient did not complete recommendation | 3 (23.1%) | |

| Primary care provider did not complete recommendation | 4 (30.7%) | |

| Quality of care | ||

| PHQ-9 score ≥10 addressed with treatment plan (n=4) | 2 treated for depression 2 for fatigue | |

| PHQ-9 item “thought you'd be better off dead” addressed with treatment plan (n=2) | Both were reassessed and neither were suicidal | |

| Address target symptoms ≥7 in severity (n=18) | 17/18 severe target symptoms addressed | |

The breathlessness and fatigue algorithms were combined as they had similar assessments.

ECG, electrocardiogram; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9; SD, standard deviation; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

The collaborative care team met weekly, with the majority attending in-person meetings with occasional attendance by phone. The team made an average of 10 recommendations per patient over the 3-month intervention period (Table 2). The most common recommendations targeted pain (25.3%) and fatigue (20.6%). Medication changes, further evaluation, and consultations were recommended. By the end of the intervention period, 85.1% of the collaborative team recommendations were followed. Reasons recommendations (14.9%) were not completed are described in Table 2.

All participants who screened positive for depression on the PHQ-9 (n=4) were either treated for depression or thought not to have a depressive disorder and treated for fatigue. Both participants who endorsed thoughts of dying on the PHQ-9 (n=2) were reassessed and found not to be suicidal. Seventeen of 18 severe target symptoms were addressed with a treatment plan.

Several of the symptoms rated “most bothersome” on the GSDS were not the symptoms targeted by the algorithms, such as sexual issues (three participants, 17.7%), numbness/tingling (two participants, 11.8%), and cough (two participants, 11.8%). There was <5% missing data on baseline and follow-up surveys.

Acceptability

Content

All but two patients reported a positive experience with the CASA intervention. Most felt the nursing component was “a good source of information” about diet, exercise, and self-monitoring of weight and blood pressure. Many said it helped with self-care. For example, one patient said, “I had made up my mind to change my life habits but didn't know how to do it.” Another said CASA was “a wake-up call to help me focus on myself.” Another described a change in behavior, “Before [CASA], I would go to [local grocery store] and get fish sticks. Now I take a bus across town to get fresh seafood.” Most perceived the nurse as “an advocate,” “someone in my corner,” or “someone watching over me.” Regarding the psychosocial component, many thought the “getting active” and pacing modules were helpful.

Structure

Almost all patients were satisfied with the frequency and phone format of CASA visits. For example, one said, “I began to look forward to the calls”; others mentioned being “sad” or that they “missed getting calls” after the program ended. Many praised the flexibility that staff offered in scheduling phone visits. Most thought that CASA should ideally be provided shortly after diagnosis.

Recommendations for changes

Several critiques emerged from the qualitative interviews. First, the phone symptom surveys (part of the nurse intervention) were perceived as repetitive and burdensome. Second, several participants thought the grief and loss module did not apply to them as they were not depressed. None of these participants appeared to have a current depressive disorder based on the PHQ-9.

Discussion

The CASA intervention was conceptually driven and aimed to improve symptoms and quality of life in patients with HF by integrating palliative and psychosocial care into chronic care using a collaborative care model of health care delivery. Both the nursing and psychosocial components of CASA provided the expected number of visits and time per visit, and the collaborative care team was able to meet and provide recommendations, 81.6% of which were completed. Based on the enrollment and intervention completion rates, intervention process data, and participant qualitative feedback, CASA was feasible and perceived as helpful. This is important because the study population was different compared with many other palliative care intervention studies. The CASA study population was a group of outpatients with symptomatic chronic illness, in contradistinction to other palliative care interventions that target a population with limited prognosis who are often inpatients or homebound.31

Changes were made to the protocol and intervention based on the self-report surveys and qualitative interviews (Table 3). The phone symptom surveys were shortened by assessing the target symptom and symptoms that had changed, not assessing every symptom during every call. The psychosocial module language was revised to be less focused on depression. As participants reported that symptoms other than the target symptoms were “most bothersome,” we decided to allow the team to target symptoms besides the four target symptoms. This created a more patient-centered intervention, but adds to its complexity. There is a balance between structuring interventions so they can be replicable and allowing flexibility to address patients' diverse needs.

Table 3.

Protocol or Intervention Changes Made

| Protocol or intervention change made | Rationale |

|---|---|

| 1. Symptom survey shortened | Phone symptom surveys were repetitive and burdensome. |

| 2. Occasional home visit allowed | Some participants requested an occasional home visit |

| 3. Module language changed to be less focused on depression | Some participants felt certain modules “didn't apply,” such as grief and loss and depression “because I'm not depressed.” |

| 4. Allowed more flexibility with modules; individually tailor so that some modules are briefly presented as “refreshers” | Some participants felt some of the modules were things they already knew and too much time was spent on them, such as pacing their energy during the day. |

| 5. Created a “menu” of available resources, such as weight loss programs, caregiver support | One participant wanted to know what other resources exist for symptoms. |

| 6. Allowed team to target symptoms besides the four target symptoms | On baseline self-report measures, symptoms besides those targeted by the intervention were rated as “most bothersome” such as cough and numbness/tingling in hands/feet. |

CASA differs from other HF disease management and palliative care interventions by integrating a structured, manualized psychosocial care protocol, using a collaborative care model, and focusing on symptoms and quality of life. HF disease management interventions have been variously defined and implemented, and although some have found reduced rates of hospitalization and mortality, the association between disease management and improved outcomes has been inconsistent.32–35 These interventions have not included psychosocial care or attempted to alleviate the diverse symptoms experienced by HF patients. In contrast, palliative care interventions have focused on improving symptoms and quality of life in HF, but have mixed results. Symptoms worsened in the intervention arm of one trial,36 and in another, common symptoms including depression and pain did not improve.37 By including structured psychosocial care to improve depression and help patients adjust to the limitations that accompany HF, and integrating psychosocial and symptom-focused care into chronic care using collaborative care, the CASA intervention aims to address the limitations of prior interventions.

Several considerations and limitations should be noted. CASA was designed as a structured intervention in order to ease dissemination if it is effective. However, as patients had various patterns of symptoms and levels of depression, changes were made to the protocol to accommodate this variability. It may be challenging to replicate a flexible intervention in which different patients have different “doses” of the intervention based on their needs. However, flexible interventions can be implemented and disseminated.38 CASA focuses primarily on symptoms and quality of life. Other components of palliative care, such as advance care planning and spiritual care, are not structured into the intervention. However, these components can still be addressed by the nurse and social worker, by discussion with PCPs, or by referral to a chaplain or community faith provider. Finally, as the majority of recruitment took place at a Veterans Affairs hospital, all the participants were male, and we did not learn if females might respond differently to the intervention.

The data from this pilot study imply that CASA is a feasible and acceptable intervention to improve symptoms and quality of life in patients with HF with a variety of backgrounds and clinical characteristics. Funding has been obtained from the National Institutes of Health for a multi-site efficacy trial (R01-NR013422) in which we plan to evaluate cost and cost-effectiveness if the intervention is successful.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolyn Turvey, PhD, who developed the original, manualized counseling intervention that we adapted for use in our trial. We would like to thank the collaborative care team members, including Priscilla Ingebrigsten, LCSW, Aaron Murray-Swank, PhD, Jamie Peterson RN, MPH, and Barbara Watson, RN.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. This study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, RRP 11-239. Dr. Bekelman is also funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs, CDA 08-022.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

References

- 1.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Allen LA, Shakar S, Kutner JS, Matlock DD: Outpatient palliative care for chronic heart failure: A case series. J Palliat Med 2011;14:815–821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bekelman DB, Havranek EP, Becker DM, et al. : Symptoms, depression, and quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 2007;13:643–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, Portenoy RK, Tennstedt SL: Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage 2008;35:594–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodlin SJ, Hauptman PJ, Arnold R, et al. : Consensus statement: Palliative and supportive care in advanced heart failure. J Card Fail 2004;10:200–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauptman PJ, Havranek EP: Integrating palliative care into heart failure care. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:374–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pantilat SZ, Steimle AE: Palliative care for patients with heart failure. JAMA 2004;291:2476–2482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bekelman DB, Nowels CT, Retrum JH, et al. : Giving voice to patients' and family caregivers' needs in chronic heart failure: Implications for palliative care programs. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1317–1324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin EH, Katon W, Von KM, et al. : Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290:2428–2429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lenz ER, Pugh LC, Milligan RA, Gift A, Suppe F: The middle-range theory of unpleasant symptoms: An update. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1997;19:14–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson IB, Cleary PD: Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA 1995;273:59–65 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. : Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10:CD006525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von KM, et al. : Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2611–2620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA: Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: A new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1245–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank D, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Kivlahan DR, Bradley KA: Effectiveness of the AUDIT-C as a screening test for alcohol misuse in three race/ethnic groups. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:781–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown RL, Leonard T, Saunders LA, Papasouliotis O: A two-item conjoint screen for alcohol and other drug problems. J Am Board Fam Pract 2001;14:95–106 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe SM, Nekolaichuk C, Beaumont C, Johnson L, Myers J, Strasser F: A multicenter study comparing two numerical versions of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System in palliative care patients. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:456–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nekolaichuk C, Watanabe S, Beaumont C: The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System: A 15-year retrospective review of validation studies (1991–2006). Palliat Med 2008;22:111–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Badger TA, Segrin C, Meek P: Development and validation of an instrument for rapidly assessing symptoms: The general symptom distress scale. J Pain Symptom Manage 2011;41:535–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D: Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002;24:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, Bosworth HB, et al. : Measuring quality of life at the end of life: Validation of the QUAL-E. Palliat Support Care 2004;2:3–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K: Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the patient health questionnaire-9. Med Care 2004;42:1194–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Monahan PO, Lowe B: Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:317–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. : 2009 focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: Developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation 2009;119:e391–e479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Higginson I: Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;2:CD005623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson MJ, Oxberry SG: The management of dyspnoea in chronic heart failure. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2010;4:63–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Del Fabbro E, Dalal S, Bruera E: Symptom control in palliative care—Part II: cachexia/anorexia and fatigue. J Palliat Med 2006;9:409–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. : Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:2099–2110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. : Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:2836–2845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turvey CL, Klein DM: Remission from depression comorbid with chronic illness and physical impairment. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:569–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fihn SD, Bucher JB, McDonell M, et al. : Collaborative care intervention for stable ischemic heart disease. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:1471–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zimmermann C, Riechelmann R, Krzyzanowska M, Rodin G, Tannock I: Effectiveness of specialized palliative care: A systematic review. JAMA 2008;299:1698–1709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Parker KM, et al. : Care management for low-risk patients with heart failure: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004;141:606–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galbreath AD, Krasuski RA, Smith B, et al. : Long-term healthcare and cost outcomes of disease management in a large, randomized, community-based population with heart failure. Circulation 2004;110:3518–3526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laramee AS, Levinsky SK, Sargent J, Ross R, Callas P: Case management in a heterogeneous congestive heart failure population: A randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:809–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith B, Forkner E, Zaslow B, et al. : Disease management produces limited quality-of-life improvements in patients with congestive heart failure: Evidence from a randomized trial in community-dwelling patients. Am J Manag Care 2005;11:701–713 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aiken LS, Butner J, Lockhart CA, Volk-Craft BE, Hamilton G, Williams FG: Outcome evaluation of a randomized trial of the PhoenixCare intervention: Program of case management and coordinated care for the seriously chronically ill. J Palliat Med 2006;9:111–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabow MW, Dibble SL, Pantilat SZ, McPhee SJ: The comprehensive care team: A controlled trial of outpatient palliative medicine consultation. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M: Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]