Abstract

There is a substantial body of literature that demonstrates that substance use and lower educational attainment are associated with poorer antiretroviral (ART) adherence, however, the nature of these relationships are not well understood. The purpose of this study was to explore whether coping styles mediate the relationship between substance use and educational attainment and ART adherence in order to better understand how these variables relate to adherence. The sample consisted of 192 HIV-positive patients (mean age = 41 years; 75.5 % male, 46.9 % heterosexual; 52.6 % with a high school/GED education or less) who were on ART. Path analysis revealed that active and avoidant coping significantly mediated the relationship between drug use and ART adherence. No form of coping was found to mediate the relationship between either binge drinking or educational attainment and adherence. Findings suggest that a focus on coping skills should be included in any multimodal intervention to increase ART adherence among HIV-positive drug using patients.

Keywords: Substance use, Educational attainment, Coping, ART adherence

Introduction

Numerous controlled clinical trials of intensive antiretroviral (ART) therapy have demonstrated that adherent patients can achieve durable viral load suppression with sustained increases in CD4 lymphocyte counts [1–4] and reduced morbidity and mortality [5–8]. The benefits of ART are clear, however its initial success and long-term effectiveness requires near perfect adherence (80–95 %) [9–11]. Not surprisingly, patients struggle to achieve these high levels of adherence [12, 13] and several studies have documented less than optimal adherence rates among patients ranging from 33 to 88 % [14–18].

There is a substantial body of literature that demonstrates that substance use (i.e., use of alcohol and other drugs) [10, 19–21] and lower educational attainment [22–24] are associated with poorer ART adherence. However, the nature of these relationships is not well understood. There is some evidence that active alcohol and drug use may interfere with individuals’ ability to regularly obtain their ART medications and that complicated ART regimens may be a poor lifestyle fit for these individuals [e.g., 21]. Even less is known about how educational attainment impacts ART adherence, however there is some evidence that adherence self-efficacy might moderate the relationship between educational attainment and ART adherence [23]. Specifically, a study by Arnsten et al. [24] found that as adherence self-efficacy increased in patients with lower educational attainment (less than a high school degree) viral failure (which was used as a proxy for behavioral adherence) also decreased. While this study highlights the important variable of adherence self-efficacy which has previously been demonstrated to directly impact adherence and mediate the relationships between other key variables and adherence [e.g., 25], it did not explore other potential mediators of the effect of education attainment on adherence behaviors. Understanding the mechanism(s) through which substance use and lower educational attainment impact adherence is important as it could contribute to the development of effective intervention programs.

One way that both substance use and lower educational attainment might impact adherence is through their association with particular types of coping strategies that positively or negatively impact ART adherence. For example, studies have shown that substance users tend to use more avoidant forms of coping (e.g., self-blame, avoidance, anger) and less active forms of coping (e.g., use of emotional support, planning) [26, 27]. Numerous studies of HIV-positive individuals (regardless of substance use status) have demonstrated that patients who rely more heavily on avoidant forms of coping evidence poorer adherence [28–34]. However, no studies have examined whether reliance on avoidant forms of coping is one of the reasons that HIV-positive substance using individuals consistently evidence lower adherence.

Similarly, while we were unable to identify any studies that have directly explored the relationship between educational attainment and coping styles in HIV-positive individuals, lower levels of education have been linked to use of avoidant styles of coping in patients with diabetes [35], cancer [36], lower back pain [37], other types of chronic pain [38], and spinal cord injury [39]. It is also known that lower levels of education are highly related to lower socioeconomic status (SES) [40, 41] and there is evidence of an association between SES and coping. Fleishman and Fogel [42] explored the relationship between income levels and coping styles in HIV/AIDS patients and found that people with lower income levels tend to utilize more avoidant coping compared to those with higher income levels. Additionally, people with higher SES (higher income and educational attainment) tend to employ more active forms of coping and less avoidant coping [40, 41]. Taken together, these findings provide some evidence that HIV-positive people with lower SES (a proxy for lower educational attainment) tend to use more avoidant forms of coping and those with higher levels of education and income tend to use more active forms of coping. Understanding the mediational role that coping styles might play in these relationships is important as it would provide clear targets for intervention and further our understanding of a theoretically grounded stress and coping model of ART adherence [e.g., 43, 44].

In addition to exploring more traditional active and avoidant coping styles, we also examined the role of religious/spiritual coping which is frequently employed by HIV-positive individuals [45, 46]. Different types of religious/spiritual coping have been described in the literature [e.g., 47], but less attention has been paid to these specific forms of religious/spiritual coping among HIV-positive individuals. One study of individuals with HIV/AIDS identified four coping patterns: deferral, collaboration, religion/spirituality seeking, and self-direction [31]. Deferral coping was defined as deference to God to provide a solution whereas collaborative coping was characterized as working together with God to cope with HIV. Religion/ spirituality seekers were defined as those who consider themselves religious/spiritual but were unfulfilled by the church, and self-directing individuals tend to rely solely on themselves to cope although they may have endorsed the idea of a higher power [31]. How these specific coping styles relate to ART adherence is still unclear, however deferral coping is a passive coping style that may be associated with poorer adherence whereas collaborative coping is active and may be associated to better adherence. Understanding the role that religious/spiritual coping might play in the association between substance use and educational attainment and ART adherence is important.

In summary, there is evidence that substance use and educational attainment are associated with poorer adherence, that coping styles are related to ART adherence, and that substance use and educational attainment are associated with coping styles. This study sought to extend the existing research by formally examining whether coping acts as a mediator. We hypothesized that coping styles (active, avoidant, religious) would mediate the relationships between substance use (binge drinking and drug use) and educational attainment on the one hand and ART adherence on the other. And more specifically that individuals who report higher levels of substance use and lower educational attainment would report higher levels of avoidant coping styles, which in turn would be associated with lower levels of ART adherence. We also hypothesized that individuals with higher levels of substance use and lower educational attainment would report higher levels of passive religious deferral coping (PRDC) and lower levels of collaborative religious coping (CRC), which in turn would be associated with lower levels of adherence.

Methods

Participants

Data for this secondary data analysis were drawn from participants enrolled in Project MOTIV8, a 3-arm randomized controlled trial to test the efficacy of novel behavioral adherence interventions for ART adherence [48]. Eligible participants were either: starting ART for the first time, making a change to their regimen or experiencing adherence problems (confirmed by provider documentation and/or HIV RNA>1000 copies/mL). Participants were also HIV-positive, ≥18 years of age, and English speaking. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, had an acute illness that would interfere with their ability to participate, did not self-administer their ART, lacked the cognitive capacity to consent, or lived outside the defined study area (70-mile radius surrounding the project offices). A total of 192 participants who completed the baseline and week 1 assessments were included in this secondary data analysis.

Procedure

Data for this secondary data analysis were collected from June 2004 to August 2009 at four HIV outpatient clinics and two private group practices in Kansas City. Clinic charts were reviewed to identify potentially eligible patients. Clinic providers introduced the study by asking patients whether they were interested in participating in an ART medication adherence study and directing interested patients to recruitment staff who explained all aspects of the study and gained informed consent. After providing informed consent, participants were randomized to one of two interventions or standard care and followed for 48 weeks. Participants provided self-reported and objective data on ART adherence as well as potential mediators and moderators at baseline and 1, 12, 24, 36, and 48 week follow-up assessment visits. Approval for the study was obtained from the appropriate Institutional Review Boards at each clinic and university setting.

Measures

Background Information

Participants provided demographic information which included educational attainment, age, gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, and SES. In order to simplify analyses we created dichotomous groups for educational attainment. After examining the distribution of educational attainment for appropriate cut-points, patients were categorized as having low educational attainment (some high school or less) or high educational attainment (high school degree/ GED or higher).

Alcohol and Drug Use

To measure substance use, participants were asked to complete an Alcohol/Substance Use Inventory that measured both the frequency and quantity of use of alcohol and drugs. For this study, we used data from the baseline administration of this measure. This measure was adapted from previously published studies [49] and asked participants to report their frequency of binge drinking over the past 30 days and their use of drugs (i.e., illicit, prescription or over the counter drugs taken in excess of the directions) from seven specific drug classifications (e.g., marijuana, cocaine, opiates, and amphetamines) over the past 3 months. Binge drinking was defined as having six or more alcoholic drinks during a single drinking occasion and response options were 0 = “did not have more than six drinks at a time,” 1 = “once during the past 30 days,” 2 = “two to three times in the past 30 days,” 3 = “one to two times a week,” 4 = “three to four times per week,” 5 = “five to six times a week,” 6 = “nearly every day,” and 7 = “every day.” Participants’ scores were recoded to represent either (0) non-binge drinking (scores of 0), (1) infrequent binge drinking (scores of 1–2), or (2) frequent binge drinking (scores of ≥3) during the past 30 days.

For drug use, response options were 1 = “never used,” 2 = “I have used, but not in the past 3 months,” 3 = “one to three times in the past 3 months,” 4 = “once a month,” 5 = “two to three times a month,” 6 = “once a week,” 7 = “two to three times a week,” 8 = “four to five times a week,” and 9 = “every day.” In order to create a summary drug use score, we first categorized participants’ responses to questions for each drug as representative of (0) non-users (scores 1–2), (1) infrequent users (scores 3–5), or (2) frequent users (scores ≥5). Scores for all substances were then summed to create a summary drug use score for each participant that could range from 0 to 14.

Coping Styles

The Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced (Brief COPE) [50] and Religious Coping (RCOPE) [47] scales were used to measure coping strategies employed. We adapted both scales to ask participants to think about their HIV disease when responding to the items. The Religious Coping scale was included because religious/spiritual coping is often employed by HIV-positive individuals [45, 46] and because we anticipated recruiting a substantial proportion of African American participants who we thought might be particularly likely to indentify religion as an important coping mechanism. The Brief COPE scale is a theoretically based 28-item self-report measure that asks about people’s general coping strategies and produces 14 subscales [50]. The Religious Coping scale, a nine-item measure composed of three subscales, assesses positive and negative methods of religious/spiritual coping [47]. Separate confirmatory factor analysis of each, the Brief COPE and RCOPE, demonstrated expected and acceptable factor loadings (all loadings>.70). Consistent with previously published studies [32, 50], analyses demonstrated good reliability for all subscales (α = .74 – .87), with the exception of the Venting (α = .35) and Self-Distraction (α = .61) subscales. To simplify analyses and reduce the risk of a Type I error, we collapsed the Brief COPE subscales into two variables, active coping and avoidant coping. The active coping variable was comprised of scores on eight styles including: active coping, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, and religion. The avoidant coping variable was made up of scores on six styles and included: self-distraction, denial, substance use, behavioral disengagement, self-blame, and venting. We decided to include the venting and self-distraction subscale in the avoidant coping variable because the inclusion of these variable improved the model fit of our final analysis. Reliability of both active (α = .75) and avoidant (α = .67) coping summary scores was acceptable. Reliability of the RCOPE subscales was also strong: collaborative religious coping (CRC; α = .94), self-directing religious coping (SDRC; α = .78), and passive religious deferral coping (PRDC; α = .84). We used Brief COPE and RCOPE data collected at the baseline visit for this study.

ART Adherence

To measure ART adherence we used the first week of data obtained from patients’ medication events monitoring system (MEMS) bottle caps. MEMS caps record the date and time of each medication bottle opening, enabling them to provide a precise, objective assessment of the timing of each dose and the patient’s pattern of pill-taking behavior over time. Participants were responsible for obtaining their own prescriptions and agreed to keep one of their ART medications in a bottle with a MEMS cap. When participants were on more than one ART medication, we monitored adherence to the drug with the most complex dosing schedule. Data were downloaded from the MEMS bottle on a regular schedule and used to construct the adherence measure which was the “percent taken” of prescribed ART doses (number of doses taken/number of doses prescribed) over the first 7 days of the study.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to explore and describe sample characteristics (i.e., age, ethnicity, education level, SES, etc.). Before conducting the main analyses, we explored the differences between control and treatment groups on 1-week ART adherence to determine if treatment group should be included as a covariate in subsequent analyses. No significant differences between groups were observed, so treatment group was not included as a covariate.

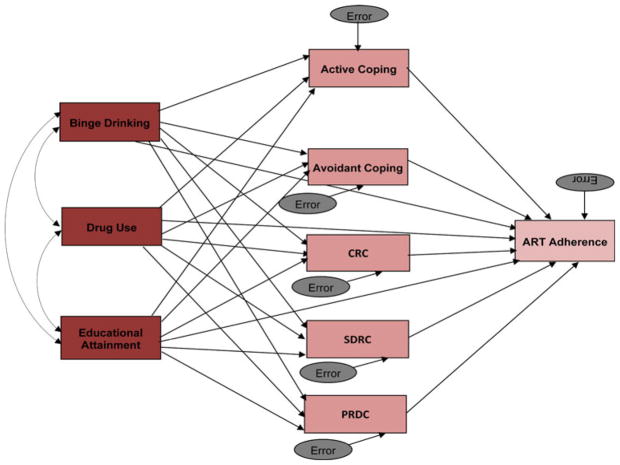

To explore the relationships between substance use, educational attainment, coping styles, and ART adherence we conducted parametric and non-parametric analyses as appropriate. We used a Path Analytic approach (a form of structural equation modeling; SEM) as outlined by MacKinnon et al. [51] to test our meditational hypothesis. Specifically, we evaluated a model in which coping (active, avoidant, religious) mediated the relationship between substance use (drug and alcohol use) and educational attainment on the one hand and adherence on the other. We used statistical software (AMOS 18) designed to test mediational models for this study. SEM models were evaluated using Chi-square values and selected alternative goodness-of-fit indices. In order to identify the most parsimonious model that explained the maximum amount of variance, we examined a variety of models using different ART adherence indicators and alternative ways of indexing substance use and coping. The original path model is displayed in Fig. 1. Consistent with other published studies, after testing the initial model non-significant paths were removed to obtain the most parsimonious model [51, 52]. Finally, given the known reciprocal relationship of substance use and coping styles and because these variables were collected at the same time point, we also examined a model in which coping styles’ relationship with adherence was mediated by binge drinking and drug use.

Fig. 1.

Initial path model: coping styles (active coping, avoidant coping, CRC, SDRC, and PRDC) as mediators of the relationship between substance use and educational attainment and ART adherence. χ2 = 153.173, df = 10, p < .05; CMIN/DF = 15.317; RMSEA = .275 (.236, .313), p < .001; CFI = .233. This model accounted for 9 % of variance

Results

Preliminary Analyses

As can be seen in Table 1, the sample consisted of 192 HIV-positive patients on ART. Participants’ average age was 41 (SD = 9.2), 75.5 % (n = 143) were male, 56.5 % (n = 108) African American, and 46.9 % (n = 90) heterosexual. Most participants, (80.7 %, n = 155) reported no binge drinking in the past 30 days and 70.8 % (n = 136) denied drug use in the past 3 months. Nearly a quarter of the sample (22.4 %) reported low (some high school or less) and 77.6 % reported high educational attainment (high school diploma/GED or higher). Overall adherence was good with 69.6 % of the sample demonstrating ≥90 % adherence to all doses over the first week of the study.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| N = 192 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 41 | 9.2 |

| 1 week ART adherence | 90.06 | 18.05 |

| Proportion ≥90 % adherence | 69.60 % | |

|

| ||

| n | % | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 143 | 75.5 |

| Female | 49 | 24.5 |

| Sexual orientation | ||

| Bi-sexual | 19 | 9.9 |

| Heterosexual | 90 | 46.9 |

| Homosexual | 74 | 38.5 |

| Decline to answer/other | 9 | 4.7 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 17 | 8.9 |

| African American | 108 | 56.5 |

| White | 45 | 23.7 |

| American Indian | 5 | 2.5 |

| More than one race/other | 16 | 8.4 |

| Education | ||

| Some high school or lower | 43 | 22.4 |

| High school degree/GED | 58 | 30.2 |

| Post high school technical training | 11 | 5.7 |

| Some college | 56 | 29.2 |

| College degree or higher | 24 | 12.6 |

| Binge drinking | ||

| Non-users | 155 | 80.7 |

| Infrequent users | 23 | 12 |

| Frequent users | 14 | 7.3 |

| Drug use | ||

| Non-users | 136 | 70.8 |

| Infrequent users | 28 | 14.6 |

| Frequent users | 28 | 14.6 |

As seen in Table 2, bivariate analyses revealed that all significant associations between binge drinking, drug use and educational attainment and Brief COPE subscales were in the expected direction (i.e., binge drinking and drug use were negatively related to active coping sub-scales and positively related to avoidant-coping sub-scales, whereas educational attainment was positively related to active coping sub-scales and negatively related to avoidant coping sub-scales). As seen in Table 3, bivariate analysis showed that binge drinking was related to ART adherence (r = −.156, p < .05) in that people with higher frequencies of binge drinking had lower levels of ART adherence. Unexpectedly, drug use was not significantly related to ART adherence (r = .021) or educational attainment (r = −.043). Table 3 also shows that participants with better ART adherence were more likely to use active coping and less likely to use avoidant coping than patients with poor adherence. None of the religious coping sub-scales evidenced significant relationships with ART adherence, however the relationship between PRDC and adherence approached significance (r = −.137, p = .06).

Table 2.

Correlations between Brief COPE subscales and binge drinking, drug use, educational attainment, and 1 week adherence

| Active coping

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | EM | IS | PR | PL | HM | AE | RE | |

| Binge drinking | −.087 | −.064 | −.036 | −.152 | −.070 | .007 | −.169 | −.035 |

| Drug use | −.154 | −.190 | −.131 | −.068 | −.142 | .001 | −.053 | −.098 |

| Educational attainment | .157 | .57 | −.019 | .139 | .090 | .172 | .000 | −.005 |

| 1 week adherence | .156 | .086 | .050 | .196 | .168 | .116 | .176 | .089 |

| Avoidant coping

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SU | SB | DN | VT | SD | BD | |

| Binge drinking | .402 | .052 | .091 | .048 | −.129 | .242 |

| Drug use | .491 | .187 | .025 | .057 | −.069 | .079 |

| Educational attainment | −.105 | −.115 | −.208 | .055 | .086 | −.152 |

| 1 week adherence | −.047 | −.038 | −.069 | −.105 | −.095 | −.179 |

Significant correlations shown in bold (p <.05)

AC = active coping, EM = use of emotional support, IS = use of instrumental support, PR = positive reframing, PL = planning, HM = humor, AE = acceptance, RE = religion, SU = substance use, SB = self-blame, DN = denial, VT = venting, SD = self-distraction, BD = behavioral disengagement

Table 3.

Correlation between binge drinking, drug use, educational attainment, active coping, avoidant coping, CRC, SDRC, PRDC, and adherence

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Binge drinking | – | |||||||

| 2. Drug use | .177* | – | ||||||

| 3. Educational attainment | −.169* | −.043 | – | |||||

| 4. Active coping | −.117 | −.172* | .120 | – | ||||

| 5. Avoidant coping | .086 | .221** | −.121 | .044 | – | |||

| 6. CRC | .127 | .127 | −.121 | .410** | −.033 | – | ||

| 7. SDRC | −.057 | .082 | .105 | −.200** | −.152* | −.516** | – | |

| 8. PRDC | .069 | −.022 | −.231** | −.037 | .211* | .386** | −.041 | – |

| 9. 1 week adherence | −.156* | .021 | .092 | .207** | −.140* | .060 | −.094 | −.137 |

CRC = collaborative religious coping, SDRC = self-directing religious coping, PRDC = passive religious deferral coping

p < .005;

p < .05

Main Analysis

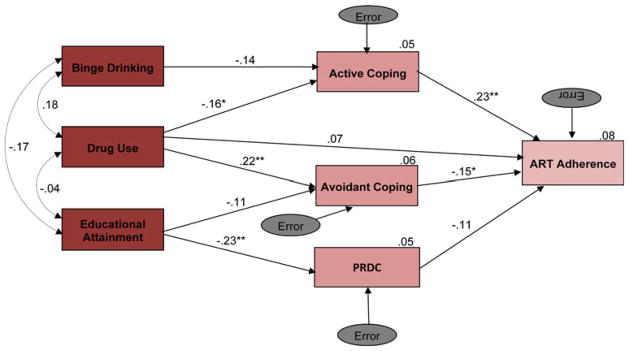

Path analysis was used to examine whether coping styles (active, avoidant, and religious coping) mediated the relationships between binge drinking, drug use, and educational attainment and ART adherence. The saturated path model (Fig. 1) did not result in a good fit (χ2 = 153.173, df = 10, p < .05), but accounted for nine percent of the variance. Following the path modeling procedures [51, 52], we removed the non-significant paths from this initial model to obtain a more parsimonious model. The final model resulted in good model fit and explained 8 % of the overall variance. The final model is displayed in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Final path model: coping styles as mediators of the relationship between substance use and educational attainment and ART adherence. Fit indices indicate good model fit: χ2 = 15.629, df = 9, p > .05; CMIN/DF = 1.737; RMSEA = .062 (.000, .112), p > .05; CFI = .855. ** p < .005; * p < .05. PRDC = passive religious deferral coping

In the final model, drug use was a significant predictor of active coping (β = −.16, p < .05) and active coping was a significant predictor of ART adherence (β = .23, p < .005). Drug use also significantly predicted avoidant coping (β = .22, p < .005) and avoidant coping significantly predicted ART adherence (β = −.15, p < .05). Binge drinking did not significantly predict active coping nor avoidant coping. The non-significant path between binge drinking and avoidant coping was removed from the final model. The non-significant path between binge drinking and active coping (β = −.14, p < .13) was retained because it improved the overall fit of the final model. Educational attainment also did not significantly predict active coping or avoidant coping, but the path to avoidant coping (β = −.11, p < .11) was retained to improve model fit.

With respect to the RCOPE, educational attainment significantly predicted PRDC (β = −.23, p < .005), but PRDC did not significantly predict ART adherence (β = −.11, p = .17). Neither binge drinking nor drug use predicted PRDC. All paths of the remaining religious coping subscales (CRC and SDRC) were not significant and their exclusion did not impact model fit, so they were removed.

Overall, results indicated that both active and avoidant coping mediated the effect of drug use (but not binge drinking or educational attainment) on ART adherence.

Additional Exploratory Analyses

Because the percentage of variance accounted for in the final model was low we also explored a variety of alternative models in which we used different ART adherence variables. Specifically, we examined models using both the total percent taken/total prescribed and percent taken within the therapeutic dose coverage window for the specific medication/total prescribed over the first 12 weeks, the 30 days prior to the 12 week assessment, and the 30 days subsequent to the 12 week data collection point. Analyses revealed adequate to good model fit, the same pattern of inter-relationship between variables, and a comparable total percent of variance accounted for each of the full models tested (range 4–8 %). We also examined models in which we combined binge drinking and substance use into a single substance use variable and active and avoidant coping into a single indicator of coping. Again we observed similar results without improvement in the percent of variance explained. Finally, due to the complicated, often reciprocal, relationship between substance use and coping we also tested an alternative path model in which avoidant and active coping were used as the predictors, binge drinking and drug use were used as mediating variables, and ART adherence was the outcome variables. This path model demonstrated poor fit and only predicted three percent of the variance (χ2 = 13.776, df = 3, p < .05, RMSEA = .133 [.068, .208], p < .05; CFI = .522).

Discussion

The main purpose of the study was to explore whether coping styles mediate the relationship between substance use (binge drinking and drug use), educational attainment, and ART adherence. A thorough understanding of the nature of the relationships among these variables is important as it could guide the development of effective interventions that target mutable variables that can assist individuals in maintaining optimal ART adherence.

Our results partially supported our hypothesis that the association between substance use (binge drinking and drug use), educational attainment, and ART adherence would be mediated by coping. Our final path model revealed that active coping was positively related to ART adherence while avoidant coping was negatively related to ART adherence. These results are consistent with prior studies that have demonstrated a link between active coping and stronger adherence [28, 33, 34]. Our results extend these prior findings to ART adherence among a diverse sample that includes a substantial proportion of African American women.

With respect to mediation, our strongest finding was that drug use was associated with less active coping, which was in turn related to poorer ART adherence. Drug use was also associated with greater use of avoidant coping, which was again associated with poorer ART adherence. Taken together these results present the first evidence that coping may mediate the association between drug use and ART adherence.

The pattern for binge drinking was quite similar to drug use with binge drinking having a negative association with active coping. Although the path from binge drinking to active coping did not reach significance, this non-significant path was retained because it improved model fit. The weaker results for binge drinking relative to drug use may be due to the low number of frequent binge drinkers in our sample (<15 %). Additional studies that purposely recruit samples with a larger percentage of substance using/abusing individuals are needed to further clarify these findings.

The overall pattern of results is consistent with previous studies linking binge drinking and drug use to less active and more avoidant coping [40, 42, 48, 53] and demonstrates that these coping patterns may lead to poorer ART adherence at least among drug users. It is possible that substance use itself is a form of avoidant coping, which in turns negatively impacts ART adherence. It is also likely that individuals with higher levels of substance use simultaneously engage in multiple forms of avoidant coping (e.g., denial, behavioral disengagement), which results in poorer adherence. For example, by employing avoidant coping styles, like denial, HIV-positive individuals may seek to avoid any reminder of their disease and therefore inconsistently take their medication or even stop ART treatment altogether. Future research should utilize larger samples to examine specific forms of avoidant coping that substance users typically employ to further elucidate their impact on ART adherence. Our findings point to the potential value of addressing coping strategies to improve ART adherence among those with drug and alcohol problems. This is important because not all treatments for substance use or adherence problems focus on coping skills training, [e.g., 54, 55] and most HIV-positive populations include a sizeable number of individuals who use/abuse substances. For example, interventions could assist HIV-positive drug using patients in developing active coping strategies such as planning, by assisting individuals to develop and execute a personalized plan for regularly obtaining medication refills. These skills have the potential to be very helpful as an inability to regularly obtain refills emerged in our pilot work and has been noted in other research as a consistent barrier for drug using patients [21]. Similarly, assisting individuals in identifying and enlisting the support of others would address the active coping strategy of Emotional Support given that previous stress and coping research has demonstrated that individuals with lower levels of social support tend to employ higher levels of avoidant coping, which in turn negatively impacts ART adherence [44]. Increasing the supportive network around HIV-positive drug using patients has the potential to not only increase adherence but will likely have secondary positive benefits in terms of stress reduction, adherence to medical regime and even mood management [e.g., 56].

With respect to educational attainment our final model revealed a significant association between lower educational attainment and greater use of PRDC, however PRDC was not significantly associated with ART adherence. Although the lack of a significant path from PRDC to adherence limits the strength of the conclusions we can draw, results do indicate increased use of this passive form of religious coping among individuals with less educational attainment. Given that the inclusion of the path from PRDC to ART adherence improved overall model fit and approached significance, and that our group has previously demonstrated a significant negative association between baseline levels of PRDC and likelihood of obtaining ≥90 % ART adherence at 12 weeks [57], future research should continue to explore this potentially important variable. Until more research is conducted, interventions that increase use of known adaptive coping skills (e.g., stress management [58] or problem-solving therapy [59]) may be particularly helpful for these individuals.

Although the results of this study provide some support for a conceptual model that helps to explain how substance use (specifically drug use) impacts adherence behavior and suggests directions for treatment, it should be acknowledged that the final model accounted for a small percent of the variance in adherence. The most likely explanation for this problem is the low percentage of substance using individuals in the sample. Unlike other research samples that focused on active substance using individuals [e.g., 20, 60], ours was a community sample which did not exclude drug using individuals, but did not selectively recruit for them either. The resulting sample was comprised of a majority of African American (57 %) who reported no binge drinking (81 %) or drug use (71 %) in the past 3 months. Of the women included in this study (n = 49), 71 % were African American. While this is a representative community sample of HIV-positive individuals in care in the local area and consistent with prior research that demonstrates that African Americans and especially African American women use less substance than other groups (e.g., Whites) [61, 62], it likely hampered our ability to demonstrate the full magnitude of the relationships of interest in this study. Despite these limitations, this study is the first to demonstrate that one way drug use negatively impacts ART adherence is likely through its association with specific coping styles.

Other limitations of this research include our use of data for the independent variables and hypothesized mediators that were collected at the same time point which prevented us from drawing conclusions regarding causality. Although a model in which we reversed the direction of the paths so that coping was used to predict substance use evidenced poor model fit, future studies should utilize longitudinal data to more fully examine these important relationships. Further, as some studies have found that effective coping is dependent on the demands of the situation [43, 63] and an individuals’ ability to be flexible in their application of coping styles to fit the situation at hand is more important than using one particular type of coping style. Exploring how coping changes over time and how those changes affect the relationships explored in this study is also important. Given the number of parameters tested in the initial path model (Fig. 1; number of parameters = 44) it is likely that our sample size was too small and may have negatively impacted model fit. However, following the guidelines of mediational analysis, we removed several non-significant paths, which resulted in good model fit. Future studies with a larger sample size should be conducted to address this limitation. Lastly, our lack of a theoretical rationale for the exploratory analyses is an additional limitation.

In spite of these limitations this study breaks new ground in providing evidence to support a meditational role for active and avoidant coping in the well established relationships between substance use on the one hand, and ART adherence on the other. Studies like this one, which help to explain the underlying mechanisms linking individual characteristics to predictors of adherence, have the potential to help identifying ways in which adherence interventions can be improved.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Mental Health (RO1 MH68197) and made possible by the participants of Project MOTIV8. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the clinicians in our participating clinics: Kansas City Free Health clinic (Sally Neville, Brooke Patterson, Craig Dietz, Edie Toubes-Klingler), Truman Medical Center (James Stanford, David Bamberger, Maithe Enriquez, Sharon Kathrens, Alan Salkind), Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center—Kansas City (Arundhati Desai, Vinutha Kumar), Kansas University Medical Center (Broderick Crawford, Himal Bajracharya, Lisa Clough, Dan Hinthorn, Michael Luchi, Stephen Waller), and Infectious Disease Specialist (Michael Driks, David McKinsey, Joe McKinsey). We also acknowledge the extraordinary efforts of our MOTIV8 team (Andrea Bradley-Ewing, Tara Carruth, Kristine Clark, Kirsten Kakolewski, Domonique Malomo Thomson, Megan Pinkston-Camp, Bradley Clark, Anthony Firner, & Robin Liston). We also acknowledge Jose Moreno for his help on the back-translation of the abstract of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Gulick RM, Mellors JW, Havlir D, et al. Treatment with indinavir, zidovudine, and lamivudine in adults with human immunodeficiency virus infection and prior antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:734–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMahon D, Lederman M, Haas DW, et al. Antiretroviral activity and safety of abacavir in combination with selected HIV-1 protease inhibitors in therapy-naïve HIV-1 infected adults. Antivir Ther. 2001;6(2):105–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saag MS, Tebas P, Sension M, et al. Randomized, double-blind comparison of two nelfinavir doses plus nucleosides in HIV-infected patients (Agouron study 511) AIDS. 2001;15(15):1971–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200110190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staszewski S, Morales-Ramirez J, Tashima KT, et al. Efavirenz plus zidovudine and lamivudine in the treatment of HIV-1 infection in adults. New Engl J Med. 1999;341(25):1865–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron DW, Heath-Chiozzi M, Danner S, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of ritonavir in advanced HIV-1 disease. Lancet. 1998;351(9102):543–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(11):725–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mocroft A, Vella S, Benfield TL, et al. Changing patterns of mortality across Europe in patients infected with HIV-1. Lancet. 1998;352(9142):1725–30. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)03201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palella FJ, Delaney KM, Moorman AC, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiIorio C, McCarty F, DePadilla L, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral medication regimens: a test of a psychosocial model. AIDS Behav. 2007;13(1):10–22. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nischal KC, Khopkar U, Saple DG. Improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2005;71(5):316–20. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.16780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson MO, Catz SL, Remien RH, et al. Theory-guided, empirically supported avenues for intervention on HIV medication nonadherence: findings from the healthy living project. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17(12):645–56. doi: 10.1089/108729103771928708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Read T, Mijch A, Fairley CK. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy: are we doing enough? Intern Med J. 2003;33(5–6):254–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-5994.2003.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Altice FL, Friedland GH. The era of adherence to HIV therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(6):503–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartlett JA. Addressing the challenges of adherence. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29(Suppl 1):S2–10. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200202011-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Halkitis PN, Parsons JT, Wolitski RJ, Remien RH. Characteristics of HIV antiretroviral treatments, access and adherence in an ethnically diverse sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2003;15(1):89–102. doi: 10.1080/095401221000039798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh N, Squier C, Sivek C, Wagener M. Determinants of compliance with antiretroviral therapy in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: prospective assessment with implications for enhancing compliance. AIDS Care. 1996;8(3):261–9. doi: 10.1080/09540129650125696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weidle PJ, Ganea CE, Irwin KL, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral medications in an inner-city population. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;22(5):498–502. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199912150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinkin CH, Barclay TR, Castellon SA, et al. Drug use and medication adherence among HIV-1 infected individuals. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):185–94. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9152-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim TW, Palepu A, Cheng DM, Libman H, Saitz R, Samet JH. Factors associated with discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients with alcohol problems. AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):1039–47. doi: 10.1080/09540120701294245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tucker JS, Orlando M, Burnam MA, Sherbourne CD, Kung FY, Guifford AL. Psychosocial mediators of antiretroviral nonadherence in HIV-positive adults with substance use and mental problems. Health Psychol. 2004;23(4):363–70. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, et al. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active anti-retroviral treatment. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):1013–21. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marc LG, Testa MA, Walker AM, et al. Educational attainment and response to HAART during initial therapy for HIV-1 infection. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(2):207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnsten JH, Li X, Mizuno Y, Knowlton AR, Gourevitch MN, Handley K, Metsch LR. Factors associated with antiretroviral therapy adherence and medication errors in HIV-infected injection drug user. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46(Suppl 2):S64–71. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31815767d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kennedy S, Goggin K, Nollen N. Adherence to HIV medications: utility of self-determination theory. Cognit Ther Res. 2004;28(5):611–28. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staiger PK, Melville F, Hides L, Kambouropoulos N, Lubman DI. Can emotion-focused coping help explain the link between posttraumatic stress disorder severity and triggers for substance use in young adults? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(2):220–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ouimette PC, Finney JW, Moos RH. Two-year posttreatment functioning and coping of substance use patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Addict Behav. 1999;33:105–14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balfour L, Kowal J, Silverman A, et al. A randomized controlled psycho-education intervention trial: improving psychological readiness for successful HIV medication adherence and reducing depression before initiating HAART. AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):830–8. doi: 10.1080/09540120500466820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grassi L, Righi R, Sighinolfi L, Makoui S, Ghinelli F. Coping styles and psychosocial-related variables in HIV-infected patients. Psychosomatics. 1998;39(4):350–9. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(98)71323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hobfoll SE, Schröder KE. Distinguishing between passive and active prosocial coping: bridging inner-city women’s mental health and AIDS risk behavior. J Soc Pers Relat. 2001;18(2):201–17. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacobson CJ, Luckhaupt SE, Delaney S, Tsevat J. Religio-biography, coping, and meaning-making among persons with HIV/ AIDS. J Sci Study Relig. 2006;45(1):39–56. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vosvick M, Koopman C, Gore-Felton C, Thoresen C, Krumboltz J, Spiegel D. Relationship of functional quality of life to strategies for coping with the stress of living with HIV/AIDS. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(1):51–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.44.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gore-Felton C, Koopman C. Behavioral mediation of the relationship between psychosocial factors and HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):569–74. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177353e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ironson G, Friedman A, Klimas N, et al. Distress, denial, and low adherence to behavioral interventions predict faster disease progression in gay men infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Int J Behav Med. 1994;1(1):90–105. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0101_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richardson A, Ander N, Nordstrom G. Persons with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: acceptance and coping ability. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(6):758–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chao HL, Tsai TY, Livneh H, Lee HC, Hsieh PC. Patients with colorectal cancer: relationships between demographic and disease characteristics and acceptance of disability. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(10):2278–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janowski K, Steuden S, Kurylowicz J. Factors accounting for psychosocial functioning in patients with low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(4):613–23. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1151-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li L, Moore D. Acceptance of disability and its correlates. J Soc Psych. 1998;138(1):13–25. doi: 10.1080/00224549809600349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodrich F, Patterson JB. Variables related to acceptance of disability in persons with spinal cord injuries. J Rehabil. 1983;49(3):26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aspinwall LG, Taylor SE. Modeling cognitive adaptation: a longitudinal investigation of the impact of individual differences and coping on college adjustment and performance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1992;63(6):989–1003. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Billings AG, Moos RH. The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. J Behav Med. 1981;4(2):139–57. doi: 10.1007/BF00844267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fleishman JA, Fogel B. Coping and depressive symptoms among people with AIDS. Health Psychol. 1994;13(2):156–69. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weaver KE, Llabre MM, Durán RE, et al. A stress and coping model of adherence and viral load in HIV-positive men and women in highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) Health Psychol. 2005;24(4):385–92. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bader A, Kremer H, Erlich-Trungenberger I, et al. An adherence typology: coping, quality of life, and physical symptoms of people with HIV/AIDS and their adherence to antiretroviral treatment. Med Sci Monit. 2006;12(12):CR493–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cotton S, Puchalski CM, Sherman SN, et al. Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(Suppl 5):S5–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pargament KI. A Report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging Working Group. Kalamazoo: 1999. Religious/spiritual coping. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goggin K, Gerkovich M, Williams K, et al. Outcomes of project MOTIV8: a RCT of novel behavioral interventions for ART adherence. Presented at the proceedings of NIMH/IAPAC international conference on HIV treatment; Miami. May 23–25, 2010; (abstract no. 62097) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Grant KA, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. Comparison of three alcohol consumption measures: a concurrent validity study. J Stud Alcohol. 1995;56(2):168–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the Brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: The Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ickovics JR, Forsyth B, Ethier KA, Harris P, Rodin J. Delayed entry into health care for women with HIV: implications of time of diagnosis for early medical intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 1996;10(1):21–4. doi: 10.1089/apc.1996.10.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miller NS, Ninonuevo FG, Klamen DL, Hoffman NG, Smith DE. Integration of treatment and posttreatment variables in predicting results of abstinence-based outpatient treatment after one year. J Psychoactive Drugs. 1997;29(3):239–48. doi: 10.1080/02791072.1997.10400197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From in-session behaviors to drinking outcomes: a casual chain for motivational interviewing. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77(6):1113–24. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koenig L, Pals SL, Bush T, Pratt Palmore M, Stratford D, Ellerbock TV. Randomized controlled trial of an intervention to prevent adherence failure among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral therapy. Health Psychol. 2008;27(2):159–69. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Finocchario-Kessler S, Catley D, Berkley-Patton J, et al. Baseline predictors of ninety percent or higher antiretroviral therapy adherence in a diverse urban sample: the role of patient autonomy and fatalistic religious beliefs. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(2):103–11. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Monti PM, Rohsnow DJ. Coping-skills training and cue-exposure therapy in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23(2):107–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chang EC, Downey CA, Salata JL. Social problem solving and positive psychological functioning: looking at the positive side of problem solving. In: Chang EC, D’Zurilla TJ, Sanna LJ, editors. Social problem solving: theory, research, and training. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henrich TJ, Lauder N, Desai MM, Sofair AN. Association of alcohol and injection drug use with immunologic and virologic responses to HAART with HIV-positive patients from urban community health clinics. J Commun Health. 2008;33(2):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cook BL, Alegria M. Racial-ethnic disparities in substance abuse treatment: the role of criminal history and socioeconomic status. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(11):1273–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.62.11.1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Turner WL, Wallace B. African American substance use: epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Violence Against Women. 2003;9(5):576–89. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vyavaharkar M, Moneyham L, Tavakoli A, et al. Social support, coping, and medication adherence among HIV-positive women with depression in rural areas of the southeastern United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(9):667–80. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]