Abstract

The purpose of this study is to utilize the Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM) to expand the construct of efficacy in the adolescent substance use context. Using survey data collected from 2,129 seventh-grade students in 39 rural schools, we examined the construct of drug refusal efficacy and demonstrated relationships among response efficacy (RE), self-efficacy (SE), and adolescent drug use. Consistent with the hypotheses, confirmatory factor analyses of a 12-item scale yielded a three-factor solution: refusal RE, alcohol-resistance self-efficacy (ASE), and marijuana-resistance self-efficacy (MSE). Refusal RE and ASE/MSE were negatively related to alcohol use and marijuana use, whereas MSE was positively associated with alcohol use. These data demonstrate that efficacy is a broader construct than typically considered in drug prevention. Prevention programs should reinforce both refusal RE and substance-specific resistance SE.

Adolescent substance use, which includes illicit use of alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs (ATOD), has been associated with numerous deleterious outcomes for teens, families, and communities (e.g., Bachman et al., 2008; Hingson & Wenxing, 2009). In order to achieve public health priorities for reducing adolescent substance use, which is one of the nation’s highest public health priorities (Healthy People 2020, n.d.), it is important to identify constructs that are associated with reduced levels of illicit adolescent substance use.

One theory that is particularly useful for understanding the likelihood of an individual engaging in a behavior such as substance use is the Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM; Witte, 1992). Although the EPPM has rarely been applied in the context of adolescent substance use (for a notable exception, see Allahverdipour et al., 2007a), it has substantially contributed to understanding of how individuals’ perceptions of threat and efficacy influence intentions to engage in health behaviors. For example, the EPPM has been used to design effective health messages in various health contexts such as hand washing (Botta, Dunker, Fenson-Hood, Maltarich, & McDonald, 2008), hearing protection (Smith et al., 2008), HIV/AIDS prevention (Chib, Lwin, Lee, Ng, & Wong, 2010), health literacy education (Gossey et al., 2011), promotion of cancer screening (Jones & Owen, 2006), and influenza vaccination (Cameron et al., 2009).

Using the EPPM to understand predictors of adolescent substance use has the potential to expand the utility of the theory as well as reconcile a major gap in the prevention literature. The goal of the current study is to achieve this aim by focusing on the concept of efficacy. Although the prevention literature has long considered self-efficacy (e.g., Carpenter & Howard, 2009), these studies lack the sophisticated EPPM conceptualization of efficacy that considers both response efficacy (RE) and self-efficacy (SE). The EPPM argument is that to perform a behavior such as refusing drug offers, one has to believe one can turn down the offer (SE) and that one’s repertoire of refusal strategies is likely to be effective (RE). One goal of the current study, then, is to extend EPPM’s conceptualization of SE and RE to adolescent substance use.

At the same time, the substance use and social cognitive literature can inform the EPPM by calling into question the unidimensional conceptualization and measurement of SE for complex health behaviors (e.g., Miles, Voorwinden, Chapman, &Wardle, 2008) such as substance use. Studies of adolescent substance use (e.g., Allahverdipour et al., 2007b), for example, have considered SE to resist offers of various substances as unidimensional construct without statistically testing the validity of that assumption using factor analysis. Although it is illegal for youth to drink alcohol or smoke tobacco or marijuana, confidence in one’s ability to refuse offers may vary by substance. For instance, a youth is likely to encounter many more offers of alcohol as compared to marijuana. Since it is possible that some individuals have strong SE for a certain behavior but weak SE for another behavior (Bandura, 2006), drug-specific SE should carefully considered. EPPM may benefit from a prevention science approach that advocates multiple dimensions of efficacy for distinct yet related behaviors such as resisting offers of illicit substances. Thus, the second purpose of this study is to examine the dimensionality of the EPPM construct of SE and refusal RE in the adolescent substance use context.

EXTENDED PARALLEL PROCESS MODEL

The Extended Parallel Process Model or EPPM (Witte, 1992, 1994) was developed based on the Parallel Process Model (Leventhal, 1970) to provide a more elaborate theoretical explanation for fear appeals. The EPPM extends the previous model by explicating two distinct appraisals (e.g., fear vs. danger control) arising from fear appeals (Witte, 1992, 1994). Witte draws on Protection Motivation Theory (PMT; Roger, 1975, 1983) to argue that the success of fear appeals can be explained through danger control appraisals and draws on the Fear-As-Acquired Drive Model (Janis, 1967) to explain the failure of fear appeals through fear control appraisals. Combining these approaches, EPPM explains that individuals respond to fear appeals messages through these appraisals.

In EPPM (Witte, 1992, 1994), two key constructs explain the acceptance or rejection of health messages: perceived threat and efficacy. Threat consists of two subcomponents, severity or one’s perception of the seriousness of the threat (e.g., using an illegal drug is a serious threat to my quality of life) and susceptibility or the perceived probability of experiencing a threat (e.g., I am likely to use an illegal drug due to peer pressure). Efficacy also consists of two underlying components, RE and SE. RE refers to the perceived effectiveness of alternative responses to a threat while SE is one’s belief about one’s ability to perform a behavior. EPPM theorizes that a message with a fear appeal is evaluated with these two components (threat and efficacy). That is, when a message on threat is greater than efficacy beliefs, individuals tend to avoid the message. On the other hand, when perceived efficacy is higher than perceived threat, messages are likely to be accepted and behaviors changed as recommended. Empirical studies support these hypothesized processes, with findings that individuals who have high efficacy and threat are more likely to accept messages while those who have low efficacy and high threat reject messages (e.g., Witte & Allen, 2000). In sum, the EPPM (Witte, 1992) proposes that perceived threat and efficacy predict responses to fear appeal messages. In other words, if individuals fail to recognize information regarding efficacy, they are motivated to avoid or deny message to eliminate fears induced by threats. In contrast, individuals are motivated to control the danger of threat when they perceive enough efficacy.

The EPPM distinction between RE and SE has been examined in a variety of health domains. Both were found to be important factors for forming behaviors and intentions in cancer prevention (Krieger, Kam, Katz, & Roberto, 2011; Krieger, Katz, Kam, & Roberto, 2012), exercise and diet promotion (e.g., McAuley, Courneya, Rudolph, & Lox, 1994), condom use (e.g., Bogale, Boer, & Seydel, 2010), osteoporosis prevention (Wurtele, 1988), and many other issues (Botta, Dunker, Fenson-Hood, Maltarich, & McDonald, 2008; Gossey et al., 2011; Smith et al., 2008). In addition, meta-analyses reveal that RE has a moderate effect and SE has a large effect on behavioral change and/or intentions (Casey, Timmbermann, Allen, Krahn, & Turkiewicz, 2009; Floyd, Prentice-Dunn, & Rogers, 2000).

Although these studies illustrate how the EPPM is useful for designing health risk messages, EPPM studies typically share several limitations. First, many studies using this framework focused on the factors that produce successful persuasive messages rather than predicting health behaviors (e.g., Gore & Bracken, 2005; Hong, 2011). In other words, most EPPM studies have investigated which manipulated components in EPPM (e.g., high efficacy/low threat or high efficacy/high threat) influence message acceptance and/or behavioral intentions, rather than modeling which components in EPPM predict health behaviors (e.g.,Maguire et al., 2010; Wong & Cappella, 2009). Moreover, EPPM research tends to rely on college student or adult samples (e.g., LaVela, Smith, & Weaver, 2007). Only a few studies (e.g., Allahverdipour et al., 2007a) have examined whether EPPM predictions hold among adolescent populations when health behaviors, particularly risky behaviors, tend to emerge (Steinberg, 2008). Finally, EPPM research has mainly focused on threat and how different types of threat can be expanded in the EPPM (e.g., Lindsey, 2005; Morrison, 2005; Nestler & Egloff, 2010; Roberto & Goodall, 2009), with less attention to the efficacy construct.

Consequently, the main purpose of this study is to utilize EPPM to expand the construct of efficacy in adolescent substance use context. Although threat assessment is considered one of the key components of the EPPM, the current context is somewhat unique in that the most salient threat to adolescents is peer pressure to use substances (Allen, Chango, Szwedo, Schad, & Marston, 2012). Accordingly, efficacy in resisting this pressure (i.e., refusal skills) has become of the focus of research attempting to understand the social processes of adolescent drug use and prevention (Hecht et al., 2008). In addition, previous studies showed that efficacy may have more influence on behavior than threat (Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., 2004; Tay, 2005; Witte, 1998). As a result, the current study focuses on efficacy. Drawing on EPPM, we examine the relationship between both SE and RE in substance use behaviors. Thus, this article is conceptually framed by EPPM, applying it to enhance our understanding of the role different types of efficacy play in resisting drug offers. We focus specifically on adolescents because this tends to be the age of substance use initiation (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012), and thus it is considered crucial to understand how youth respond to substance offers during this crucial developmental stage.

EFFICACY AND SUBSTANCE USE

We start by examining existing research on SE and adolescent substance use. Previous research demonstrates that SE in refusing substance offers and substance use are negatively associated with each other. Several studies demonstrated this negative relationship including those focusing on drinking (Annis & Davies, 1988; McKay, Maisto, & O’Farell, 1993) and smoking (Condiotte & Lichtenstein, 1981). Barkin, Smith, and DuRant (2002) showed that SE was negatively related to current substance use and to youths’ anticipated substance use of the following year. In addition, Masten, Best, and Garmezy (1990) reported that SE is a protective factor that encourages adaption of recommended behaviors (e.g., “avoiding drug use”) among high-risk adolescents.

As yet, however, substance use research has barely considered RE. While many evidence-based prevention interventions are based on a social influence model (Flay, 2009; Tobler et al., 2000) that focuses on teaching resistance skills, little is known about whether youth become convinced that these skills will actually be effective in resisting substance offers from peers, family, and others. It may be that merely believing one can resist (SE) is adequate, although EPPM would suggest otherwise.

Based on this literature review and EPPM-based theorizing, we reasoned that SE and RE should influence drug use decisions. As already noted, both forms of efficacy are influential in determining other health behaviors. Adolescents, faced with drug offers, must feel that they are capable of resisting (SE) and that their refusal strategies will be effective (refusal RE). Although SE and RE are theorized as distinct constructs, most substance research based on EPPM (e.g., Moscato et al., 2001; Shahab, Hall, & Marteau, 2007) has not reported whether these two types of efficacy are statistically distinguishable. For example, Allahverdipour et al. (2007a) reported the internal consistency of both the SE and RE scales, but did not report confirmatory factor analysis to examine the predicted two-dimensional structure. Furthermore, the developmental literature suggests that age should be considered to test theoretical concepts (Byrne, Davenport, Mazanov, 2007; Wolfe et al., 2001). Thus, it is important to examine whether youth can distinguish between SE and RE in the substance domain. Consequently, the following hypothesis is posed:

-

H1

Refusal response efficacy and self-efficacy are separate dimensions in substance domains.

According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1989), individuals who believe they have low ability to perform certain behavior (e.g., self-efficacy) are less likely to engage in the behavior. Furthermore, EPPM (Witte, 1992) and Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers, 1983) hypothesized that people who believe they can perform a behavior confidently (i.e., refusing drug offers) and also see those behaviors (i.e., refusal strategies) as effective tend to enact the behavior. That is, youth who possess both SE and refusal RE for refusing offers are less likely to use substances. Thus, H2 predicts:

-

H2

Refusal response efficacy and self-efficacy are negatively related to substance use.

DOMAIN SPECIFICITY AND SELF-EFFICACY

Recently, Bandura (2006) argued that domain-specific SE is more relevant to any specific behavior than global efficacy. He reasoned that we cannot do everything well but, rather, selectively cultivate SE in certain domains. For example, we may have high SE in starting relationships but be less certain in our ability to maintain them. As a result, SE is likely to differ depending on the domain. In other words, youth may have different levels of drug resistance SE depending on the type of substance that is offered. This makes sense since youth initiate substances at different rates (Kosterman et al., 2000) and thus have more or less experience with various substances. One recent factor-analytic study supports this conceptualization, finding drug-specific SE for alcohol and marijuana resistance (e.g., Carpenter & Howard, 2009).

We propose, then, that feeling efficacious in resisting alcohol offers may not mean feeling efficacious in resisting marijuana offers. Although it is illegal for youth to consume both alcohol and marijuana, the acceptability, prevalence, and accessibility of both drugs vary (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012). Kosterman et al. (2000) showed that adolescents commonly reported initiating alcohol use before age 13 years, but the initiation of marijuana use occurred later. Due to these reasons, youths are more likely to encounter offers of alcohol as compared to offers of marijuana. Since SE develops from past performance and intentional effort (Kanfer, 1987), drug-specific-resistance SE is likely to be differentiated based on past experience with offers of a particular substance. Similarly, youth with specific drug-resistance SE are less likely to use a specific drug because they can easily resist the specific drug offer. However, it is unknown if one specific drug-resistance SE predicts resistance to offers of other types of drugs because SE in one specific domain can influence behavior in similar domain (Bandura, 2006). Based on this literature, we hypothesize that SE will differ based on the substance offered and pose these sub-hypotheses for H2 and RQ1.

-

H2a

Refusal response efficacy and alcohol-resistance self-efficacy are negatively related to alcohol use.

-

H2b

Refusal response efficacy and marijuana-resistance self-efficacy are negatively related to marijuana use.

-

RQ1

What is the relationship between (a) alcohol-resistance self-efficacy and marijuana use and (b) marijuana-resistance self-efficacy and alcohol use?

The Relationship Between Self-Efficacy and Response Efficacy

Finally, it is unclear how SE and RE relate to each other. The EPPM argues that both elements are needed for effective messages, but, as yet, we do not know if both are needed for effective health behaviors. It is possible that the two components, refusal RE and SE, have an interaction effect beyond their own unique effects. That is, combining both strong SE and strong RE enhances or strengthens attitudes or behavior change, while combining both weak SE and weak RE decreases individuals’ intentions and behavior change. Research examining these effects is mixed. On the one hand, Wurtele and Maddux (1987) experimentally induced both types of efficacy. Their findings demonstrate that individuals’ intentions to exercise were significantly lower in the SE and RE absent condition compared with the only SE present condition, whereas the conditions in which only one or the other type of efficacy was induced produced nonsignificant findings. Similarly, Catania, Kegeles, and Coates (1990) claimed that individuals changed their behaviors only when they reported both high RE and SE, suggesting an interaction. However, other studies failed to produce a significant interaction effect when considering other health behaviors (e.g., Longshore, Anglin, & Hsieh, 1997).

We posit that refusal RE moderates the relationship between SE and behavior. Generally, people perform a certain behavior when they believe they have a strong ability to do so (Bandura, 1982). However, this relationship can change when individuals consider the effectiveness of behavior to achieve a specific goal (Keller, 2006). That is, individuals who perceive a low likelihood that certain behaviors will overcome threats may not engage in those behaviors even though they believe that they are able to do so. In contrast, individuals who believe that a certain behavior is effective to overcome threats are more likely to perform the behavior when they have strong ability to do so. Thus, the following research questions are posed:

-

RQ2

Does refusal response efficacy moderate (a) the association between alcohol-resistance self-efficacy and alcohol use or (b) the association between marijuana-resistance self-efficacy and marijuana use?

METHOD

The current study was conducted as part of a larger evaluation of a middle school prevention intervention trial. Even though the data are from an evaluation of a school-based substance-prevention program, only pretest data were used for the study and thus all participants are included regardless of experimental condition.

Participants

The participants in this study were 2,129 seventh-grade students who participated in the Drug Resistance Strategies project in 39 rural Pennsylvania and Ohio schools in the fall of 2009. Of the 2,129 students, 1,078 were male, 1,041 were female, 1,937 were White, 40 were Native American, 32 were African American, 52 were Hispanic, and the remaining 68 student were of other ethnic backgrounds. The average age of the students was 12.3 years (SD = 0.50, range: 11–14).

Procedures

The Penn State University (PSU) Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures. The Survey Research Center at PSU administrated a 45-minute questionnaire during regular school hours in science, health, or homeroom classes. The administrators were trained by one of the principal investigators. Prior to the main study, a pilot study was performed to determine if there were any instrumental issues in the survey. All participants had both passive parental consent and participant assent.

Measures

Refusal response efficacy

Refusal RE was measured by four items derived and modified from Witte, Cameron, McKeon, and Berkowitz (1996) to examine efficacy in resisting substance offers. The students responded to the four items by indicating the degree to which each statement was true based on a 4-point scale ranging from completely true (1) through false (4). The items stated that (a) simply saying no would be an effective way to resist alcohol and other drug use, (b) offering an explanation would be an effective way to resist alcohol and other drug use, (c) avoiding the situation would be an effective way to resist alcohol and other drug use, and (d) leaving would be an effective way to resist alcohol and other drug use. Items were recoded such that higher scores indicated higher refusal response efficacy.

Alcohol/marijuana resistance self-efficacy

Items for alcohol/marijuana-resistance self-efficacy were measured using a 4-point response format ranging from very easy (scored as 1) to very hard, respectively. After recoding items, higher values indicated greater substance-resistance SE. Alcohol resistance self-efficacy was measured using the following scenario (Hansen & McNeal, 1997): “Suppose someone you know offered you a drink of alcohol, and you did not want it.” Marijuana resistance self-efficacy was measured using a similar scenario, with “some marijuana” replacing “a drink of alcohol.” Resistance self-efficacy was measured for both alcohol and marijuana using the following four items: “How easy would it be for you (1) to refuse it, (2) to explain why you didn’t want it, (3) to avoid the situation in the first place, and (4) to just to leave the situation?” These four possible descriptions (e.g., refuse, explain, avoid, and leave) have been found in drug resistance across age groups, geographic areas, and ethnicities (Hecht & Miller-Day, 2009; Pettigrew, Miller-Day, Hecht, & Krieger, 2011).

Alcohol/marijuana use

Measurement of substances use was modified based on previous studies (Hansen & Graham, 1991). The seventh graders were asked to report on cumulative lifetime consumption and use during the 30 days prior to the survey. Responses for these items were rated on a 10-point scale for alcohol and a 7-point scale for marijuana ranging from “none” (1) to “more than 100 drinks” (10) for alcohol use and “more than 30 times” (7) for marijuana use. Students also reported the number of days they had drunk alcohol and used marijuana during the past 30 days, respectively. Table 1 shows these responses.

TABLE 1.

Summary Statistics and Correlation Among Dependent and Independent Variables (n = 2129)

| M | SD | Cronbach’s alpha | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Refusal response efficacy | 3.21 | 0.02 | 0.77 | — | ||||

| 2. Alcohol-resistance self-efficacy | 3.57 | 0.02 | 0.83 | .37*** | — | |||

| 3. Marijuana-resistance self-efficacy | 3.8 | 0.01 | 0.86 | .30*** | .66*** | — | ||

| 4. Alcohol use | 2.05 | 0.03 | 0.79 | −.21*** | −.35*** | −.16*** | — | |

| 5. Marijuana use | 1.06 | 0.01 | 0.90 | −.14*** | −.20*** | −.28*** | .42*** | — |

p < .001.

Data Analysis Strategy

To assess the dimensionality of the efficacy scales, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was implemented using LISREL 8.72 (Joreskog & Sorbom, 1998). In order to deal with missingness, the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) method was used (Graham, Cumsille, & Elek-Fisk, 2003). Many studies (e.g., Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Schafer & Graham, 2002) have demonstrated that FIML generates unbiased estimates with data missing at random (MAR) and provides robust estimates even though the MAR assumption is not completely met.

Because a large sample size influences the significance of the χ2 test, three indices of practical fit for model evaluation were employed: the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Browne & Cudeck, 1993), the non-normed fit index (NNFI) (Bentler & Bonett, 1980), and the comparative fit index (CFI) (Bentler, 1990; McDonald & Marsh, 1990). For RMSEA, a smaller value indicates a better fit, while a greater value indicates a better fit for CFI and NNFI. Following the convention of Hu and Bentler (1998), RMSEA < .06, CFI > .95, and NNFI > .95 were considered to be a “good fit.”

In order to address the components of hypothesis 2 and research question 1, structural equation modeling (SEM) was implemented with LISREL 8.72. Interaction terms between two continuous variables also were included in SEM using an orthogonalizing approach (Little, Bovaird, & Widaman, 2006) because it handles the presence of measurement error within the statistical model (Little, Card, Bovaird, Preacher, & Crandall, 2007). Furthermore, an orthogonalizing approach for interactions in SEM has several merits, such as (1) reducing unnecessary multicollinearity and (2) providing stable estimates and direct interpretations of the dependent variable (Little, Bovaird, & Widaman, 2006).

Separate models were run for the two outcomes (e.g., alcohol use and marijuana use). Three types of efficacies were entered as exogenous variables, while the type of self-reported substance use was entered as the endogenous variable in each case. Preliminary research showed that there were no significant demographic effects (age, gender, and ethnicity) on the relationship between substance use and the three efficacies. Thus, we excluded demographic characteristics in the further analysis. Due to the nested data, intraclass correlations (ICC) were examined across all variables used (e.g., alcohol use, refusal self-efficacy). Across all variables, the ICC was less than 0.03. According to Heck (2001), a small ICC (e.g., < .05) does not result in biased parameter estimations. Consequently, we used SEM without accounting for intraclass correlation.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the means, related standard deviations for each of the factors, and the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients along with the correlations between factors.

Dimensionality of Efficacy

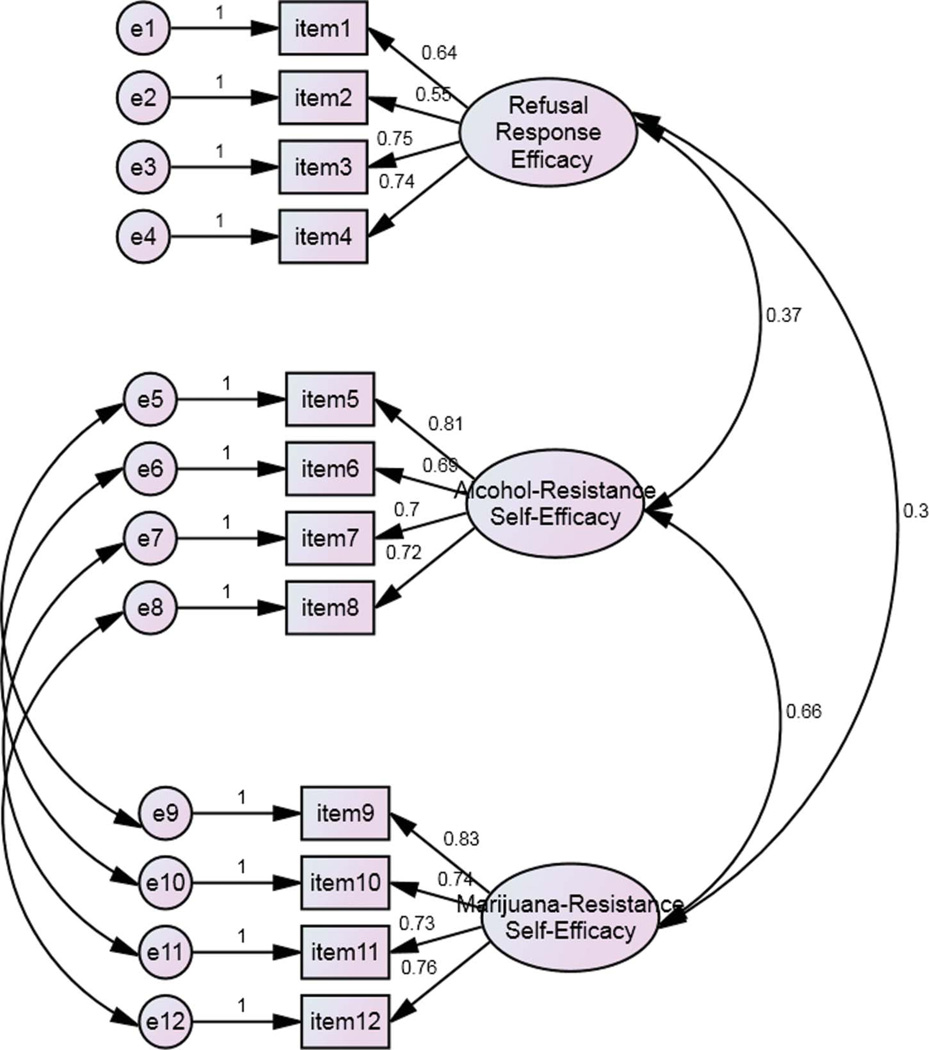

In order to answer H1—the dimensionality of perceived efficacy— the predicted three-factor CFA consisting of refusal RE, alcohol-resistance self-efficacy (ASE), and marijuana-resistance self-efficacy (MSE) was examined. First, we tested a three-factor model that did not estimate residual covariances. The model was statistically significant, χ2(47) = 336.2, p < .001, because of the large sample size of the study (n = 2129) and sensitivity of the sample size on the chi-square test. The practical model fit indices revealed that the three-factor model was not acceptable, χ2(51) = 1864.4, RMSEA = .130, NNFI = .805, CFI = .849.

Because the correlation between ASE and MSE was reasonably high (r = .74 in three-factor-I model) while the correlations between refusal RE and ASE (r = .38) and MSE (r = .30) were low, a two-factor model (i.e., refusal RE and drug resistance SE) was tested next. The two-factor model, however, was a bad fit to the data given the overall pattern of fit indices, χ2(53) = 2744.7, RMSEA = .155, NNFI = .721, CFI = .776.

Theoretically and practically, youth are expected to use similar strategies to refuse drug offers across substance-use domains. That is, the same strategies would work regardless of the substance offered. For example, youth may use the same refusal strategies across substance (e.g., “saying no” strategy to resist alcohol and marijuana). As such, we allowed for estimates of residual covariances between each strategy of each substance (e.g., “saying no” to alcohol and “saying no” to marijuana). The model-fit indices showed that the three-factor models estimating residual covariances (see Figure 1) appeared to be a good fit to the data given the overall pattern of practical fit indices, χ2(47) = 336.2, RMSEA = .054, NNFI = .966, CFI = .976. In addition, the factor loadings on each factor appeared to be acceptable (Byrne, 1994; Kline, 2005), ranging from .55 to .75 for refusal RE, from .69 to .72 for ASE, and from .73 to .83 for MSE. Thus, as predicted, we found that efficacy has three dimensions.

FIGURE 1.

Factor structure of efficacy (color figure available online).

Relationship Between Substance Use and Dimensions of Efficacy

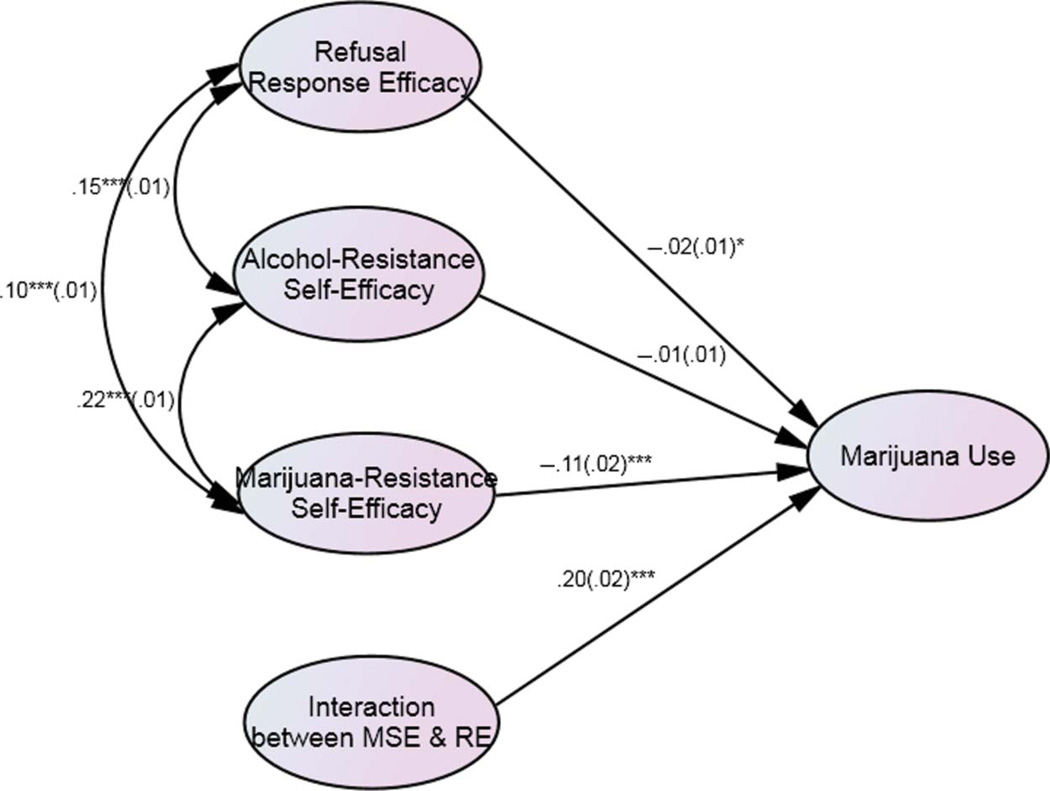

SEM was conducted to test H2. H2a and H2b, which predicted that both SE and RE would be negatively associated with alcohol and marijuana use, as well as to answer RQ1, which questioned the relationships (a) between MSE and alcohol use and (b) between ASE and marijuana use. As Figure 2 shows, the alcohol-use model including the interaction between refusal RE and ASE yielded a good fit, χ2(401) = 1601.7, CFI = .966, NNFI = .961, RMSEA = .038, 90% confidence interval (CI) = .036, .04. Refusal RE (b [unstandardized estimates] = −.13, β [standardized estimates] = −.10, t = −3.26, p < .01) and ASE (b = −.51, β = −.39, t = −10.47, p < .001) both were negatively related to alcohol use. Unexpectedly, MSE (b = .20, β = .12, t = 3.48, p < .001) was a significant but positive predictor of alcohol use. For marijuana use (see Figure 3), the overall model also revealed a good fit to the data, χ2(401) = 1563.4, CFI = .972, NNFI = .968, RMSEA = .037, 90% CI = .035, .039. As predicted, refusal RE (b = −.02, β = −.06, t = −2.17, p < .05) and MSE (b = −.11, β = −.25, t = −7.63, p < .001) were negatively related to marijuana use but ASE (b = −.01, β = −.02, t = −0.44, p > .05) was not significantly related.

FIGURE 2.

The relationship between efficacies and alcohol use. The path weights in the graph are unstandardized. RE, refusal response efficacy; ASE, alcohol-resistance self-efficacy (color figure available online).

FIGURE 3.

The relationship between efficacies and marijuana use. The path weights in the graph are unstandardized. RE, refusal response efficacy; MSE, marijuana-resistance self-efficacy (color figure available online).

RQ2a and RQ2b asked whether refusal RE moderates the relationship between ASE and alcohol use as well as the relationship between MSE and marijuana use, respectively. For alcohol use (RQ2a), refusal RE moderated the relationship between ASE and alcohol use, (b = .15, β = .09, t = 3.30, p < .05). In all, 14% of the variance in alcohol use (R2 = .14) was explained by all of the factors including the interaction, while the main effects explained 13% of the variance. As Figure 4 shows, the slope for seventh graders with higher refusal RE was less steep compared with the one for youth with lower refusal RE. In other words, the relationship between ASE and alcohol use for youths with higher refusal RE was less negative than for youth with lower refusal RE. RE was a significant moderator of relationship between ASE and alcohol use

FIGURE 4.

The interactive effect of refusal response efficacy and alcohol-resistance self-efficacy on alcohol use. RE, refusal response efficacy; ASE, alcohol-resistance self-efficacy (color figure available online).

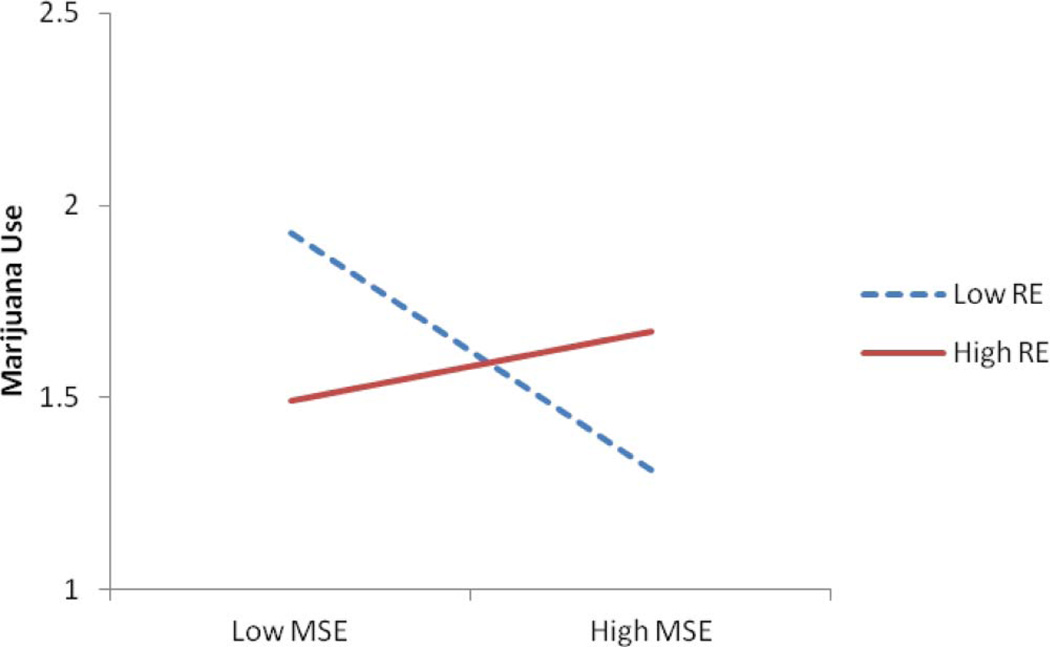

For marijuana use (RQ2b), when the interaction involving refusal RE as a moderator of relationship between MSE and marijuana use was entered in the model, together they explained an additional 13% of the variance in marijuana use (R2 = .21). That is, refusal RE significantly moderated the association between MSE and marijuana use, b = .20, β = .36, t =13.18, p<.001. As shown in Figure 5, for youth with high refusal RE, the relationship between MSE and marijuana use was positive whereas for youth with low refusal RE, the association between MSE and marijuana use was negative. Again, there was an interaction, and this anomalous finding is discussed in the next section.

FIGURE 5.

The interactive effect of refusal response efficacy and marijuana-resistance self-efficacy on marijuana use. RE, refusal response efficacy; MSE, marijuana-resistance self-efficacy (color figure available online).

DISCUSSION

The primary purpose of this study was to explicate a more elaborate conceptualization of adolescents’ efficacy in refusing substance offers. We argued based on previous theory and research that there are two types of efficacy: refusal response efficacy and substance-specified resistance self-efficacy (e.g., ASE and MSE). Consistent with our predictions, multidimensionality was found in these data based on confirmatory factor analysis, with separate factors emerging for drug-specific resistance SEs and refusal RE.

Next we examined the relationship between these forms of efficacy and adolescent substance use. Controlling for substance-specific resistance SE, refusal RE was a significant predictor for alcohol use and marijuana use. That is, participants believe that there is a common and effective way of refusing drug offers. Also, consistent with previous theorizing, there were separate SEs for resisting marijuana and alcohol offers. Moreover, consistent with predictions, these forms of efficacy are related to substance use, although the pattern was complicated by the breakdown of resistance SE by substance.

In the current study, the REAL (refuse, explain, avoid, and leave) refusal strategies were examined. Since these strategies are used across substances, age cohorts, and cultural groups (Miller, Alberts, Hecht, Trost, & Krizek, 2000; Pettigrew, Miller-Day, Hecht, & Krieger, 2011), it is not surprising that respondents find them efficacious across substances in this study. Consistent with previous literature (Bandura, 2006; Carpenter & Howard, 2009), individuals perceive differential SEs across drug domains (i.e., separate marijuana and alcohol SEs) even though drug-specific SEs are associated with one another. In other words, youth perceive ASE and MSE as separate but positively correlated constructs.

Overall, the greater the ASE and MSE individuals had, the less likely they were to drink alcohol and use marijuana, respectively (see Figures 2 and 3). At the same time, there were some variations in the relationships between ASE/MSE and alcohol/marijuana use. More specifically, the magnitude of the relationship between alcohol use and ASE was greater than the magnitude of the relationship between alcohol use and MSE. That is, having drug-specific SE prevents youth from using a specific substance, which is consistent with previous efficacy literature (e.g., Bandura, 2006).

The unexpectedly positive relationship between MSE and alcohol use should be carefully discussed. This anomalous relationship may be explained by differential experiences with these substances. Alcohol use is much more common (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012), and the illicit nature of marijuana makes use more deviant (although both substances are, of course, illegal for this age group). Thus, youth who use marijuana are more likely to be offered and to experience a wider range of substances such as alcohol and tobacco (Pacula, 1998). Assuming that previous exposure to a substance is related to developing drug-resistance SE, experiencing marijuana offers can possibly enhance these youths’MSE.Meanwhile, these youth can engage in drinking alcohol regularly because it is a relatively common illegal behavior for them compared with smoking marijuana, and thus there is the positive connection between their MSE and alcohol use. We should approach this interpretation with caution because overall use rates were quite low for all substances in this sample, especially marijuana, and these findings may reflect only a small, high-risk subgroup in the overall population that has experienced multiple substance use. Our cross-section design also suggests caution in interpretation of these findings. Thus, this conclusion is speculative and awaits further research.

Our findings also show that refusal RE moderates the relationship between ASE and alcohol use and MSE and marijuana use, respectively. However, the role of refusal RE as a moderator differs for each substance. For alcohol use, as predicted, the relationship between ASE and alcohol use was negative and refusal RE efficacy weakened the strength of this relationship (see Figure 4). In other words, for youth with low refusal RE, ASE had a stronger negative relationship to alcohol use compared to the relationship among youth with high refusal RE. Youth who have low refusal RE (i.e., do not believe that the refusal strategies are likely to be effective) are more likely to drink unless they also have high level of SE (i.e., believe strongly in their own ability to refuse alcohol offers). On the other hand, youth with higher levels of refusal RE rely less on their own ASE to avoid drinking because they are aware that their refusal strategies are effective.

On the other hand, compared with alcohol use, refusal RE plays a more complex role for marijuana use. For youth with high refusal RE, the relationship between MSE and marijuana use was positive, but for youth with low refusal RE the relationship was negative (see Figure 5). In other words, if youth have low refusal RE, MSE makes them less likely to engage in smoking marijuana. However, if youth have high refusal RE, MSE is positively related to marijuana use. This appears counterintuitive (i.e., why would MSE increase marijuana use among this group?) but may be explained by their past experience. Youth who strongly believed their refusal strategies were effective probably recognized that effectiveness through their past experiences with offers. Because of their experiences with past marijuana offers, they were confident they possessed effective strategies to resist offers if they wanted to do so (i.e., have high RE and high MSE). This is consistent with the literature that argues that efficacy is formed through experience (e.g., Bandura, 1986; Bandura & Wood, 1989). Possibly, adolescents with high refusal RE perceived that they could refuse marijuana offers if they wanted to, yet this small subpopulation was generally disinclined to want to refuse.

It may be useful for future studies to examine these complex findings by drawing on additional behavior health theories, such as the theory of planned behavior (TPB; Ajzen, 1985). The TPB would advocate the importance of assessing student’s attitudes and subjective norms regarding marijuana use in addition to perceptions of efficacy (or perceived behavior control). In other words, it is likely that although students had high resistance efficacy, they may have had positive attitudes toward marijuana use and perceptions that marijuana use was socially normative.

Theoretical implications

The findings demonstrate that, consistent with EPPM-derived predictions, drug-specific resistance SE and refusal RE are generally protective factors in substance use among adolescence. This finding is consistent with previous literature for other health behaviors (Stephens et al., 2009). Also, the finding is consistent with Bandura’s (2006) theorizing that a global conceptualization of efficacy does not capture differences in one’s sense of SE across domains.

However, in most previous EPPM studies, what we are calling drug-specific resistance SE (SE in other EPPM studies) is seen as a single dimension and researchers assumed that RE does not differentially influence the relationship between SE and psychological factors (Cismaru & Lavack, 2007; Roger, 1983). For example, PMT, one of the forerunners of EPPM, views SE as an additional effect on RE, operationalizing “efficacy” as the sum of SE and RE (Cismaru & Lavck, 2007; Floyd, Prentice-Dunn, & Rogers, 2000). In other words, PMT assumed that there was no interaction between RE and SE. However, other empirical studies have found interactions between RE and SE (e.g., Wurtele & Maddux, 1987). Thus, our finding shows that refusal RE moderated the relationship between drug-specific resistance SE and the specific substance use, at least in the adolescent substance use domain. As demonstrated in this study, the relationship between SE and RE may vary depending on the risk level of the behavioral domain (i.e., different substances). Thus, further research should examine how and why RE acts as a moderator not only for youths’ drug resistance domain but also other health behaviors.

As noted earlier, additional theories maybe needed to explain the complex patterns of mediation and moderation reported in this study. Further investigation should be conducted to find out how and when these relationships differ.

Practical Implications

The findings may have important implications for designing substance use prevention interventions. These findings are qualified by the limitations noted in the next section, although they suggest future directions in prevention practices. Based on the current findings, it appears that interventions should target a variety of drug-specific SEs. Even though individuals might develop alcohol-resistance SE, this may only helpful in refusing alcohol offers but not marijuana offers. Thus, practitioners should design antidrug messages that target SE related to a variety of substances in universal interventions.

Second, our findings suggest that RE also is crucial for teaching youth to refuse drug offers. Unfortunately, most drug-prevention programs for youth focus on teaching and evaluating only SE (e.g., Botvin, 2000; Cujpers, 2002). The inclusion of refusal RE in drug-prevention program curriculum may enable youth to be more capable of resisting drug offers and decreasing substance use. Individuals seem to employ similar evidence-based strategies (REAL) in refusing various substances (Miller, et al., 2000), and their confidence in these strategies effectiveness is related to decreased use. Thus, individuals not only must be trained how to use the REAL strategies when receiving both alcohol and marijuana offers but also must be convinced by the prevention intervention that this strategy works equally well for both or even either substance. So, while prevention interventions teach resistance strategies, they may want to do a better job convincing the target audience members that the strategies they are being taught will actually work when faced with substance offers they wish to turn down.

It is possible that youth with high MSE are more likely to use substances in some situations. As noted earlier, this anomalous finding requires further investigation before altering our approach to implementation. It may be, for example, that youth who have highly positive attitudes toward substance use and experience with offers and refusals engage in substance use in spite of high refusal skills. It is unlikely that youth use substances every time they are offered and thus these users are likely to have efficacy but still use on certain occasions. This implies that refusal skills are only one of factors to include in interventions. Hecht and Miller-Day (2009), for example, utilized Communication Competence Theory to design their intervention, calling upon knowledge and motivation in addition to skills to intervene in adolescent drug use. This approach is consistent with prevention research suggesting a shift from refusal skills to one emphasizing life skills, social influence, and/or socioemotional learning (Tobler, 2000).

Limitations and Future Research

Although this study provides support for our hypotheses and generated a number of theoretical and practical implications, there are several limitations in this study and suggestions for future directions regarding RE and SE in refusing substance offers. One limitation is the use of cross-sectional data. As a result, we caution interpreting the findings of the current study to suggest that increasing MSE in prevention programs increases alcohol use for youth. In prevention programs, most youth learn refusal skills regardless of previous substance experiences and many findings support the conclusion that teaching refusal skills is helpful for this population (Tobler, et al., 2000). In addition, future research should examine how youth’s SE can develop through other sources (e.g., prior exposure to substances, previous experience successfully refusing a drug offer) and how naturally developed SE is associated with changes in substance use over time. This will require longitudinal data and an examination of developmental processes.

Second, rural, predominantly white adolescents participated in this study. Thus, we cannot generalize the findings in the study beyond rural areas or to other ethnic groups, as different results may be found with an urban or suburban samples. For example, rural youth may have more similar levels of RE and SE than urban youth because rural youth are more likely to be homogeneous and to have strong social networks (Sampson & Groves, 1989). Besides, rural and urban youth may have difference experiences regarding substance use (Martino, Ellickson, & McCaffrey, 2008) that influences the relationships between RE/SE and substance use.

Third, this study did not include cigarette-resistance SE, for a number of reasons. Primarily, we were limited in the length of the survey for practical reasons (i.e., developmental stage of participants). We included alcohol because it is the most commonly used substance in this age group (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2012) and marijuana because it is the most commonly used illicit substance for adults (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011). Given the complexity of perceived efficacy and the usefulness of substance-specific resistance SE, cigarette-resistance SE also should be studied.

Finally, threat associated with substance use (i.e., severity and susceptibility) was not included in this study. Previous research suggests efficacy is the stronger factor (Roskos-Ewoldsen et al., 2004; Tay, 2005; Witte, 1998), and we were interested in focusing on the interactions among RE, MSE, and ASE. However, these two-way interactions may change if threat is included. As a result, now that these relationships have been described, it would be interesting to test the role that threat plays along with these forms of efficacies in adolescent drug use. More specifically, research should examine how social threats (e.g., losing friends) can differentiate the relationship between efficacy and behavior because youth may use substances due to fear of disconnection from peer network even though they have strong efficacy. Similarly, the severity of threat may alter these relationships, as well.

CONCLUSION

This article’s findings indicate that, consistent with EPPM-based predictions, efficacy in refusing substance offers is more complex than the unidimensional construct found in most previous drug prevention studies. Consistent with theory, refusal RE and drug-resistance SE were successfully differentiated. In addition, drug-resistance SE appears to differ in terms of the type of substance offered. Both types of efficacy are related to substance use, although the interaction patterns indicate that this relationship is also complex. At the same time, the study extends EPPM by examining health behaviors rather than health messages, studying a younger population than is typical, and demonstrating differential efficacies for different substance domains.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This publication was supported by grant number R01DA021670 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Pennsylvania State University (Michael Hecht, principal investigator). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contributor Information

Hye Jeong Choi, Department of Communication Arts and Sciences Pennsylvania State University.

Janice L. Krieger, School of Communication Ohio State University

Michael L. Hecht, Department of Communication Arts and Sciences Pennsylvania State University

REFERENCES

- Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Action control: From cognition to behavior. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1985. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdipour H, MacIntyre R, Hidarnia A, Schafii F, Kzamnegade A, Ghaleiha A, Emami A. Assessing protective factors against drug abuse among high school students: Self-control and the extended parallel process model. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2007a;18:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Allahverdipour H, Farhadinasab A, Galeeiha A, Mirzaee E. Behavioral intention to avoid drug abuse works as a protective factor among adolescent. Journal of Research on Health Sciences. 2007b;7:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Chango J, Szwedo D, Schad M, Marston E. Predictors of susceptibility to peer influence regarding substance use in adolescence. Child Development. 2012;83:337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01682.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annis HM, Davis CS. Self-efficacy and the prevention of alcoholic relapse: Initial findings from a treatment trial. In: Baker TB, Cannon DS, editors. Assessment and treatment of addictive disorders. New York, NY: Praeger; 1988. pp. 88–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O’Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Johnston LD, Freedman-Doan P, Messersmith EE. The education-drug use connection: How successes and failures in school relate to adolescent smoking, drinking, drug use and delinquency. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist. 1982;37:122–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social-cognitive view. Engle-wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Humana agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist. 1989;44:1175–1184. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.44.9.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan T, editors. Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents. Greenwich, CT: Information Age; 2006. pp. 307–337. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Wood RE. Effect of perceived controllability and performance standards on self-regulation of complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:805–814. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkin SL, Smith KS, DuRant RH. Social skills and attitudes associated with substance use behaviors among young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30:448–454. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bogale GW, Boer H, Seydel ER. Condom use among low-literature, rural females in Ethiopia: The role of vulnerability to HIV infection, condom attitude, and self-efficacy. ADIS Care. 2010;22:851–857. doi: 10.1080/09540120903483026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botta RA, Dunker K, Fenson-Hood K, Maltarich S, McDonald L. Using a relevant threat, EPPM and interpersonal communication to change hand-washing behaviours on campus. Journal of Communication in Healthcare. 2008;1:373–381. [Google Scholar]

- Botvin GJ. Preventing drug abuse in schools: Social and competence enhancement approaches targeting individual-level etiological factors. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25:887–897. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with EQS and EQS/Windows. London, UK: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne DG, Davenport SC, Mazanov J. Profiles of adolescent stress: The development of the adolescent stress questionnaire (ASQ) Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:393–416. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron KA, Rintamaki LS, Kamanda-Kosseh M, Noskin GA, Baker DW, Makoul G. Using theoretical constructs to identify key issues for targeted message design: African American seniors’ perceptions about influenza and the influenza vaccination. Health Communication. 2009;24:316–326. doi: 10.1080/10410230902889258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catania JA, Kegeles S, Coates T. Toward an understanding of risk behavior: An AIDS risk reduction model. Health Education Quarterly. 1990;17:53–92. doi: 10.1177/109019819001700107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey MK, Timmermann LT, Allen M, Krahn S, Turkiewicz KL. Response and self-efficacy of condom use: A meta-analysis of this important element of AIDS education and prevention. Southern Communication Journal. 2009;74:57–78. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter CM, Howard D. Development of a drug use resistance self-efficacy scale. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2009;33:147–157. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.33.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cismaru M, Lavack AM. Interaction effects and combinatorial rules governing protection motivation theory variables: A new model. Marketing Theory. 2007;7:249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Condiotte MM, Lichtenstein E. Self-efficacy and relapse in smoking cessation programs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1981;49:648–658. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.49.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chib AI, Lwin MO, Lee Z, Ng VW, Wong PHP. Learning AIDS in Singapore: Examining the effectiveness of HIV/AIDS efficacy messages for adolescents using ICTs. Knowledge Management & E-Learning: An International Journal. 2010;2:169–187. [Google Scholar]

- Cujpers P. Effective ingredients of school-based drug prevention programs: A systematic review. Addictive Behavior. 2002;27:1009–1023. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00295-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK, Bandalos DL. The relative performance of full information maximum likelihood estimation for missing data in structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling. 2001;8:430–457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR. The promise of long-term effectiveness of school-based smoking prevention programs: A critical review of reviews. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2009;5:1185–1187. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd DL, Prentice-Dunn S, Rogers RW. A meta-analysis of research on protection motivation theory. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2000;30:407–429. [Google Scholar]

- Feigelman S, Li X, Stanton B. Perceived risks and benefits of alcohol, cigarette, and drug use among urban low-income African-American early adolescents. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1995;72:57–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore TD, Bracken CC. Testing the theoretical design of a health risk message: Reexaming the major tenets of the Extended Parallel Process Model. Health Education & Behavior. 2005;32:27–41. doi: 10.1177/1090198104266901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gossey JT, Whitney SN, Crouch MA, Jibaja-Weiss ML, Zhang H, Volk RJ. Promoting knowledge of statins in patients with low health literacy using an audio booklet. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2011;5:397–403. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S19995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Cumsille PE, Elek-Fisk E. Methods of handling missing data. In: Schinka JA, Velicer WF, editors. Research methods in psychology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2003. pp. 87–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, Graham JW. Preventing alcohol, marijuana, and cigarette use among adolescents: Peer pressure resistance training versus establishing conservative norms. Preventive Medicine. 1991;20:414–430. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(91)90039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen WB, McNeal RB. How D.A.R.E. works: An examination of program effects on mediating variables. Health Education Behavior. 1997;24:165–176. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthy People (n.d.) Adolescent health. Retrieved from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicId=2.

- Hecht ML, Elek E, Wagstaff DA, Kam JA, Marsiglia F, Dustman P, Harthun M. Immediate and short-term effects of the 5th grade version of the Keepin’it Real substance use prevention intervention. Journal of Drug Education. 2008;38:225–251. doi: 10.2190/DE.38.3.c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht ML, Miller-Day M. The Drug Resistance Strategies Project: Using narrative theory to enhance adolescents’ communication competence. In: Frey L, Cissna K, editors. Routledge handbook of applied communication. New York, NY: Routledge; 2009. pp. 535–557. [Google Scholar]

- Heck RH. Multilevel modeling with SEM. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, editors. New developments and techniques in structural equation modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.; 2001. pp. 89–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Wenxing Z. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1477–1478. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong H. An extension of the Extended Parallel Process Model in television health news: The influence of health consciousness on individual message processing and acceptance. Health Communication. 2011;26:343–353. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.551580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Janis IL. Effects of fear arousal on attitude change: Recent developments in theory and experimental research. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 3. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1967. pp. 166–225. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SC, Owen N. Using fear appeals to promote cancer screening-are we scaring the wrong people? International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing. 2006;11:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2011. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with SIMPLIS command language. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kanfer R. Task-specific motivation: An integrative approach to issues of measurement, mechanisms, processes and determinants. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 1987;5:237–264. [Google Scholar]

- Keller PA. Regulatory focus and efficacy of health messages. Journal of Consumer Research. 2006;33:109–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R, Hawkins D, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: Patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90:360–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger JL, Kam JA, Katz ML, Roberto AJ. Does mother know best? An actor-partner model of college-age women’s human papillomavirus vaccination behavior. Human Communication Research. 2011;37:107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger JL, Katz ML, Kam JA, Roberto A. Appalachian and non-Appalachian pediatricians’ encouragement of human papillomavirus vaccine: Implications for health disparities. Women’s Health Issues. 2012;22:e19–e26. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVela SL, Smith B, Weaver FM. Perceived risk for influenza in Veterans with spinal cord injuries and disorders. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2007;52:458–462. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H. Findings and theory in the study of fear communication. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 5. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1970. pp. 119–186. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey LLM. Anticipated guilt as behavioral motivation: An examination of appeals to help unknown others through bone marrow donation. Human Communication Research. 2005;31:453–481. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Bovaird JA, Widaman KF. On the merits of orthogonalizing powered and product terms: Implications for modeling interactions among latent variables. Structural Equation Modeling. 2006;13:497–519. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Card NA, Bovaird JA, Preacher KJ, Crandall CS. Structural equation modeling of mediation and moderation with contextual factors. In: Little TD, Bovaird JA, Card NA, editors. Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.; 2007. pp. 207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Longshore D, Anglin MD, Hsieh S. Intended sex with fewer partners: An empirical test of the AIDS risk reduction model among injection drug users. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1997;27:187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire KC, Gardner J, Sopory P, Jian G, Amschlinger MRJ, Moreno M, Piccone G. Formative research regarding kidney disease health information in a Latino American sample: Associations among message frame, threat, efficacy, message effectiveness, and behavioural intention. Communication Education. 2010;59:344–359. [Google Scholar]

- Martino SC, Ellickson PL, McCaffrey DF. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early to late adolescence: A comparison of rural and urban youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69:430–440. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- McAuley E, Courneya KS, Rudolph DL, Lox CL. Enhancing exercise adherence in middle-aged males and females. Preventive Medicine. 1994;23:498–506. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald RP, Marsh HW. Choosing a multivariate model: Noncentrality and goodness of fit. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:247–255. [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Maisto SA, O’Farrell TJ. End-of-treatment self-efficacy, aftercare, and drinking outcomes of alcoholic men. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:1078–1083. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles A, Voorwinden S, Chapman S, Wardle J. Psychological predictors of cancer information avoidance among older adults: The role of cancer fear and fatalism. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2008;17:1872–1879. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MA, Alberts JK, Hecht ML, Trost M, Krizek RL. Adolescent relationships and drug use. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison K. Motivating women and men to take protective action against rape: Examining direct and indirect persuasive fear appeals. Health Communication. 2005;18:237–256. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1803_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moscato S, Black DR, Blue CL, Mattson M, Galer-Unti RA, Coster DC. Evaluating a fear appeal message to reduce alcohol use among “Greeks”. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2001;25:481–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler S, Egloff B. When scary messages backfire: Influence of dispositional cognitive avoidance on the effectiveness of threat communications. Journal of Research in Personality. 2010;44:137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Pacula RL. Adolescent alcohol and marijuana consumption: Is there really a gateway effect? Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1998. Working paper no. 6348. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew J, Miller-Day M, Hecht ML, Krieger J. Alcohol and other drug resistance strategies employed by rural adolescents. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2011;39:103–122. doi: 10.1080/00909882.2011.556139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberto AJ, Goodall CE. Using the extended parallel process model to explain physicians’ decisions to test their patients for kidney disease. Journal of Health Communication. 2009;14:400–412. doi: 10.1080/10810730902873935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. Journal of Psychology. 1975;91:93–114. doi: 10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roger RW. Cognitive and physiological processes in fear appeals and attitude change: A revised theory of protection motivation. In: Cacioppo JT, Petty RE, editors. Social psychophysiology. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1983. pp. 153–176. [Google Scholar]

- Roskos-Ewoldsen DR, Yu HJ, Rhodes N. Fear appeal messages affect accessibility of attitudes toward the threat and adaptive behaviours. Communication Monographs. 2004;71:49–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Groves WB. Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. American Journal of Sociology. 1989;94:774–802. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahab L, Hall S, Marteau T. Showing smokers with vascular disease images of their arteries to motivate cessation: A pilot study. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2007;12:275–283. doi: 10.1348/135910706X109684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SW, Rosenman KD, Kotowski MR, Glazer E, McFeters C, Keesecker NM, Law A. Using the EPPM to create and evaluate the effectiveness of brochures to increase the use of hearing protection in farmers and landscape workers. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2008;36:200–218. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. A social neuroscience perspective on adolescent risk-taking. Developmental Review. 2008;28:78–106. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens P, Sloboda Z, Stephens RC, Marquette JC, Hawthorne RD, Williams JE. Universal school-based substance abuse prevention programs: Modeling targeted mediators and outcomes for adolescent cigarette, alcohol and marijuana use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;102:19–29. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. (NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658). [Google Scholar]

- Tay R. The effectiveness of enforcement and publicity campaigns on serious crashes involving young male drivers: Are drinking driving and speeding similar? Accident Analysis and Prevention. 2005;37:922–929. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler N. Lessons learned. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;20:261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler NS, Roona MR, Ochshorn P, Marshall DG, Streke AV, Stackpole KM. School-based adolescent drug prevention programs: 1998 meta-analysis. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2000;20:275–336. [Google Scholar]

- Witte K, Cameron KA, McKeon JK, Berkowitz JM. Predicting risk behaviors: Development and validation of a diagnostic scale. Journal of Health Communication. 1996;1:317–341. doi: 10.1080/108107396127988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte K. Putting the fear back into fear appeals: The extended parallel process model. Communication Monographs. 1992;59:329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Witte K. Fear control and danger control: A test of the Extended Parallel Process Model (EPPM) Communication Monographs. 1994;61:113–134. [Google Scholar]

- Witte K. Fear as motivator, fear as inhibitor: Using the extended parallel process model to explain fear appeal successes and failures. In: Andersen PA, Guerrero LK, editors. Handbook of communication and emotion: Research, theory, applications, and contexts. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1998. pp. 424–451. [Google Scholar]

- Witte K, Allen M. A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Education & Behavior. 2000;27:591–615. doi: 10.1177/109019810002700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong NCH, Cappella JN. Antismoking threat and efficacy appeals: Effects on smoking cessation intentions for smokers with low and high readiness to quit. Journal of Applied Communication Research. 2009;37:1–20. doi: 10.1080/00909880802593928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe DA, Scott K, Reitzel-Jaffe D, Wekerle C, Grasley C, Straatman A. Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:277–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele SK, Maddux JE. Relative contributions of protection motivation theory components in predicting exercise intentions and behavior. Health Psychology. 1987;6:453–466. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.6.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurtele SK. Increasing women’s calcium intake: The role of health beliefs, intentions, and health value. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1988;18:627–639. [Google Scholar]