Abstract

Objectives

Chronic constipation in diabetes mellitus is associated with colonic motor dysfunction and is managed with laxatives. Cholinesterase inhibitors increase colonic motility. This study evaluated the effects of a cholinesterase inhibitor on gastrointestinal and colonic transit and bowel function in diabetic patients with constipation.

Design

After a 9-day baseline period, 30 patients (mean±SEM age 50±2 years) with diabetes mellitus (18 type 1, 12 type 2) and chronic constipation without defaecatory disorder were randomised to oral placebo or pyridostigmine, starting with 60 mg three times a day, increasing by 60 mg every third day up to the maximum tolerated dose or 120 mg three times a day; this dose was maintained for 7 days. Gastrointestinal and colonic transit (assessed by scintigraphy) and bowel function were evaluated at baseline and the final 3 and 7 days of treatment, respectively. Treatment effects were compared using analysis of covariance, with gender, body mass index and baseline colonic transit as covariates.

Results

19 patients (63%) had moderate or severe autonomic dysfunction; 16 (53%) had diabetic retinopathy. 14 of 16 patients randomised to pyridostigmine tolerated 360 mg daily; two patients took 180 mg daily. Compared with placebo (mean±SEM 1.98±0.17 (baseline), 1.84±0.16 (treatment)), pyridostigmine accelerated (1.96±0.18 (baseline), 2.45±0.2 units (treatment), p<0.01) overall colonic transit at 24 h, but not gastric emptying or small-intestinal transit. Treatment effects on stool frequency, consistency and ease of passage were significant (p≤0.04). Cholinergic side effects were somewhat more common with pyridostigmine (p=0.14) than with placebo.

Conclusions

Cholinesterase inhibition with oral pyridostigmine accelerates colonic transit and improves bowel function in diabetic patients with chronic constipation.

Clinical trial registration number

TrialRegNo (NCT 00276406).

INTRODUCTION

Community surveys suggest that chronic constipation is the most common gastrointestinal (GI) symptom of diabetes mellitus (DM).1–3 To date, there are no controlled therapeutic trials for this disorder. Potential mechanisms for diabetic enteric dysfunction include extrinsic denervation or enteric neuropathy. The former are manifest in the observation of autovagotomy and gastric acid hyposecretion,4 the association of impaired gastric emptying in patients with vagal dysfunction,5 and external anal sphincter weakness, which results in faecal incontinence in patients with longstanding DM.6 Enteric neural degeneration has been described in animal models of diabetes7; this dysfunction probably occurs independently of the process of extrinsic denervation, since there is no evidence of trans-synaptic degeneration in the nervous system. Both types of neural mechanism may involve loss of the excitatory transmitter, acetylcholine. By increasing the availability of acetylcholine in the myenteric plexus and at the synapse between extrinsic and intrinsic or enteric nerves, the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, neostigmine, administered intravenously increased colonic motor activity in healthy subjects and diabetic patients with constipation.8,9 Neostigmine is also effective in reducing colonic distention in acute colonic pseudo-obstruction.10 Uncontrolled studies suggest that the longer-acting acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, pyridostigmine, improved constipation in Parkinson’s disease11 and autonomic neuropathy.12,13 It is conceivable that, because extrinsic denervation is associated with denervation sensitivity,14–16 the GI effects of cholinesterase inhibitors may be more pronounced in patients with autonomic (parasympathetic) neurological involvement. In a trial of 126 patients with post-polio syndrome, 55% of patients treated with a relatively low dose of pyridostigmine (60 mg three times a day orally) developed diarrhoea, compared with 19% of patients treated with placebo.17 However, the effects of pyridostigmine on symptoms and colonic transit in patients with DM and chronic constipation have not been systematically evaluated. Our hypothesis was that pyridostigmine improves GI symptoms and colonic transit in patients with DM and constipation. The aim of this study was to assess the effects of pyridostigmine on symptoms and GI and colonic transit in constipated patients with DM.

METHODS

This was a single-site, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised clinical trial comparing the pharmacodynamic effects of pyridostigmine at a maximum dose of 120 mg three times a day and placebo administered orally in diabetic patients with chronic constipation. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave informed consent. This study was registered on Clinical Trials.gov (NCT 00276406).

Participants

We enrolled 30 diabetic patients with chronic constipation (22 women) aged 18–70 years (mean±SEM 50±2 years), based on Rome II criteria,18 who were referred for consideration for participation in this study or responded to a public advertisement. Exclusion criteria included any structural disorder affecting the GI tract or an evacuation disorder, as documented by a careful history of bowel habits, digital rectal examination, and a rectal balloon expulsion test in all patients.19 Patients with abdominal surgery (other than appendectomy, cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, tubal ligation or inguinal hernia repair), ECG abnormalities (ie, second or third degree AV block, prolonged QT interval, or resting heart rate <45/min) or clinically significant cardiovascular, respiratory or renal disease were not eligible to participate. With the exception of dietary fibre supplements, medication used to treat constipation was discontinued before the study. Stimulant laxatives (eg, bisacodyl or glycerol) and enemas were only permitted as ‘rescue agents’—that is, if subjects did not have a bowel movement for two consecutive days during the study. Drugs permitted during the study were: aspirin, warfarin, thyroid or oestrogen replacement therapy, low-dose aspirin (81 mg/day), oral contraceptives, antihypertensive agents (eg, adrenergic α or β2 antagonists, calcium channel blockers, ACE inhibitors), Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-co enzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase inhibitors, antidepressants (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRIs) or low-dose tricyclic agents up to 50 mg/day), and drugs for DM. All women with childbearing potential had to have a negative pregnancy test within 48 h of the study.

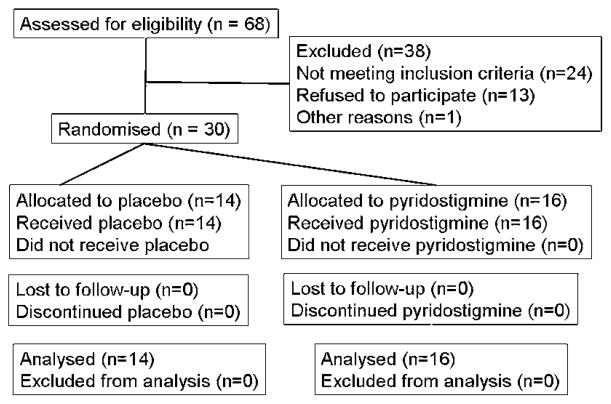

Study design and medication

Patients who satisfied eligibility criteria and provided informed consent during a screening visit proceeded to baseline (pretreatment) and treatment periods (figure 1). During the baseline period (9 days), baseline GI and colonic transit, autonomic functions, and bowel symptoms (ie, daily diaries) were assessed. During the treatment period, participants were evenly randomised to placebo or pyridostigmine; randomisation was balanced by age, gender, presence of autonomic neuropathy, and baseline colonic transit time, categorised as a geometric centre for colonic transit at 24 h (GC24) of <1.7 or ≥1.7. All clinical and laboratory study personnel were blinded throughout the study until all data were analysed.

Figure 1.

Study design. Bowel habits and gastrointestinal (GI) transit was recorded during the baseline (B) and medication (M) phases. tid, three times a day.

Pyridostigmine is a quaternary ammonium compound, has an oral bioavailability of 11.5–18.9%, and is primarily excreted by the kidneys.13 For myasthenia gravis and orthostic hypertension, the pyridostigmine dose varies from 60 to 1500 mg/day17,20; the medication is administered three times a day, because its average Tmax is 1–2 h and duration of action is 3–6 h. Because the optimum dose of oral pyridostigmine required to manage GI symptoms is unknown, pyridostigmine (Mayo Pharmacy) and matching placebo (Mayo Pharmacy) were started at 60 mg three times a day and increased by 60 mg every third day (ie, over 10 days) up to the maximum tolerated dose or 120 mg three times a day. Thereafter, this dose was maintained for 7 days. The randomisation schema provided by ARZ was loaded into Mayo Research Pharmacy’s Electronic Randomisation Access Database. Research pharmacy staff entered patient information into the database, including patient identifiers and stratification variables. The electronic database generated a randomisation confirmation sheet listing the assigned treatment. Research pharmacists dispensed the assigned treatment in a blinded manner. Active and placebo treatments were identical in appearance and dispensed in identical containers.

The study was conducted between May 2006 and October 2010. Patients were monitored for side effects by phone calls throughout the study and in person during the GI transit study.

GI and colonic transit measurements

An established and validated scintigraphic method was used to measure GI and colonic transit on days 7 to 9 of the baseline period and 14 to 17 of the treatment period.21–23 For each study, a delayed-release capsule containing 111In was administered in the early morning after at least 8 h fasting. After the capsule emptied from the stomach, as documented by its position relative to radioisotopic markers placed on the anterior iliac crests, a radiolabelled meal comprising two scrambled eggs labelled with technetium-99m (99mTc)-sulphur colloid, one slice of whole wheat bread, and one glass of skim milk was given (315 kcal). This meal was used to measure gastric and small-bowel transit. Subjects ingested standardised meals for lunch (450 kcal) and dinner (510 kcal) at 4 and 8 h after the radiolabelled meal, respectively. Abdominal scans were obtained every hour for the first 6 h (the first 4 h for the assessment of gastric emptying) and at 8, 24 and 48 h after ingestion of the 111In capsule.

Transit data were analysed by quantifying counts in the stomach, the ascending, transverse, descending, and combined sigmoid colon, and the rectum using a variable region-of-interest program. These counts were corrected for isotope decay, tissue attenuation, and down scatter of 111In counts in the 99mTc window. Gastric emptying half-time (t1/2) is a measure of the time for 50% of the radiolabelled meal (identifiable by radio-labelled tracer) to empty from the stomach. Colonic filling at 6 h (ie, the proportion of the radiolabelled meal in the colon at 6 h) is an indirect measurement of small-bowel transit time. Ascending colon (AC) emptying was summarised by the t1/2 calculated by linear interpolation of values on the AC emptying curve. Overall colonic transit was summarised as the colonic geometric centre (GC) at specified times: the GC is the weighted average of counts in the different colonic regions (AC, transverse (TC), descending (DC), rectosigmoid (RS)) and stool, respectively, 1 to 5. Thus, at any time, the proportion of counts in each colonic region is multiplied by its weighting factor as follows:

Thus a higher GC reflects a faster colonic transit. The mean normal colonic transit at 24 h is 2.65 (range 1.7–3.8).21 The primary end points were the AC emptying t1/2 and the colonic GC at 24 h (GC24). The colonic GC24 end point is responsive to treatment with secretagogues or prokinetics such as linaclotide, tegaserod and renzapride in previous pharmacodynamic studies using the same methods in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-C) or functional constipation.24–26 Further scintigraphic assessments were the GC at 48 h (GC48), the gastric emptying t1/2, and colonic filling at 6 h.

Daily stool diaries

During 9 days of the baseline period and during 17 days of the treatment period, each patient noted each bowel movement with the exact time and with the description of stool consistency according to the Bristol Stool Form Scale (ranging from 1 (hard lumps) to 7 (watery))27 and the ease of passage (ranging from 1 (manual disimpaction) to 7 (incontinence)) and answered whether or not they felt they had completely emptied their bowels (1, ‘yes’; 0, ‘no’).26 The diaries therefore contained the values for the time to first bowel movement after first drug intake (defined as the number of hours between administration of the first dose of study medication and occurrence of the first bowel movement thereafter), stool consistency, stool frequency, ease of passage and sense of completely emptying their bowels.

Autonomic functions

Postganglionic sudomotor, cardiovagal and adrenergic functions were evaluated by validated techniques.28 Postganglionic sympathetic sudomotor axons were evaluated by the quantitative sudomotor axon reflex test at four sites (forearm, proximal lateral leg, medial distal leg and proximal foot).29 This test measures the sweat output in response to iontophoresis of acetylcholine; the stimulus and response were recorded in different compartments of a multicompartmental sweat cell. Cardiovagal functions were evaluated by heart-rate responses to deep breathing and the Valsalva ratio. Heart-rate response to deep breathing was the heart-rate range with the subject supine and breathing at 6 breaths per minute. For the Valsalva manoeuvre, the subject was rested and recumbent and was asked to maintain a column of mercury at 40 mm Hg for 15 s. The Valsalva ratio is the ratio of maximal-to-minimal heart rate.30 Adrenergic function was evaluated by blood pressure and heart-rate responses, monitored continuously (Finapres monitor; Ohmeda, Englewood, Colorado, USA), to a Valsalva manoeuvre and head-up tilt. The results of the autonomic battery of tests were corrected for confounding effects of age and gender. The Composite Autonomic Severity Score (CASS) consists of three subscores: sudomotor (CASS-sudo; 0–3); cardiovagal (CASS-vag; 0–3); and adrenergic (CASS-adr; 0–4).29 The total score and subset scores provide an evaluation of the severity and distribution of autonomic failure.

Statistical analysis

The intent-to-treat analysis used all randomised patients. An analysis of covariance was used to compare treatment groups incorporating the baseline value (for all end points), gender (for gastric emptying, colonic filling at 6 h) and body mass index (colonic transit) as covariates. Bowel diaries were analysed by computing the mean scores for the 9-day baseline period and separately for the last 7 days of the treatment period (ie, when pyridostigmine dose was stable) in each subject. Individual subject treatment period mean bowel function scores were then compared using a similar analysis of covariance model, with the corresponding individual subject baseline mean bowel function score and gender as covariates. The analysis incorporated Bonferroni corrections for two comparisons pertaining to colonic transit (ie, GC24 and GC48). After institutional review board approval, interim analyses were performed to demonstrate progress for a grant-renewal application. Thus there was no intent to stop the trial early, and this analysis was performed by the study statistician without unblinding other investigators. Data is expressed as mean ± SEM.

Sample size estimate

In previous studies from our laboratory, the mean GC24 for colonic transit in diabetic patients was 2.50 with a SD of 0.6.31 A sample size of 15 subjects per group provided 80% power (based on a two-sample t test and two-sided α level of 0.05) to identify a difference of 0.64 unit in GC24 between placebo and pyridostigmine. The proposed analysis of variance should have similar power to detect somewhat smaller differences between groups by incorporating corresponding baseline values as a covariate. Differences >1 GC24 unit are generally considered to be clinically relevant.

RESULTS

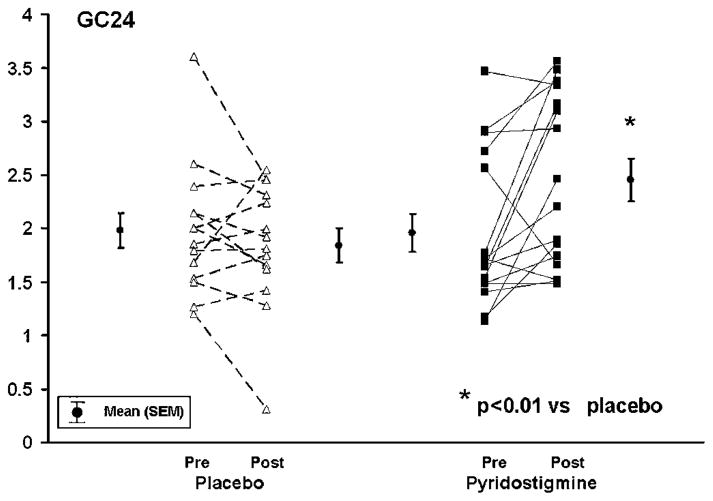

Participants, study conduct and completion

Sixty-eight patients were assessed for eligibility to participate in the study, as shown in figure 2. Twenty-four were ineligible because they were older than 70 years, were taking non-permissible medication (eg, narcotics), had significant coexistent medical conditions, or a rectal evacuation disorder. Thirteen subjects were eligible but declined to participate in the study. One patient consented but was withdrawn because of severe hyperglycaemia during the baseline period. Hence 30 patients were enrolled in the study, and all 30 completed all study procedures.

Figure 2.

Consort diagram. All randomised patients completed studies and were included in the analysis.

Demographic and baseline colonic transit data of all randomised patients are shown in table 1. Patients had DM for 23±2 years. In 23 patients, constipation symptoms began after DM was diagnosed. In the remaining seven patients, constipation symptoms predated the diagnosis of DM but had worsened since that diagnosis. Patients were unsatisfied with their bowel habits and current treatment of constipation. Twenty-six patients were taking oral agents, suppositories and/or enemas for constipation; the remaining four were receiving fibre supplements but had tried other agents previously. The distribution of patients with type 1 and 2 DM, haemoglobin A1C (HbA1c), autonomic neuropathy, and baseline colonic transit were similar in the two treatment groups. HbA1c was abnormally high (>7%) in 22 patients; of these patients, 10 received placebo and 12 received pyridostigmine. Six patients, evenly split between placebo and pyridostigmine, had HbA1c ≥9%, indicative of markedly suboptimal glycaemic control. Sixteen patients (53%) had diabetic retinopathy; nine had background and seven had proliferative retinopathy. Twenty-five patients were receiving insulin, eight one or more oral hypoglycaemic agents, and two were taking exenatide. Four patients each were taking metformin in the pyridostigmine and placebo groups, and two were taking a calcium channel blocker (diltizem, amlodipine), which did not affect the severity of the constipation symptoms. No patients were receiving opiates, colesevelam, α-glucosidase inhibitors or dipeptidel peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-IV) inhibitors; one used tramadol intermittently. The CASS score indicated no (CASS=0, five patients), mild (CASS 1–3; 14 patients), moderate (CASS 4–6; nine patients) or severe (CASS 7–10, two patients) autonomic failure. Nineteen patients, including nine of 14 patients with overall mild autonomic dysfunction, had moderate or severe dysfunctions affecting one or more components (eg, vagal dysfunction). Thus nine, 12, and six patients had moderate or severe sudomotor, vagal or adrenergic dysfunction, respectively. However, moderate-severe autonomic dysfunctions were not associated with baseline delayed colonic transit.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline clinical features

| Feature | Placebo | Pyridostigmine |

|---|---|---|

| No of patients | 14 | 16 |

| Age (years) | 52±3.1 | 48±2.8 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.65±1.6 | 27.94±1.1 |

| No of patients with type I DM | 8 | 10 |

| Duration of DM (years) | 22±3 | 25±4 |

| HbA1c (%) | 7.7±0.3 | 8.1±0.4 |

| No of patients with moderate or severe overall autonomic dysfunction | 5 | 6 |

| No of patients with diabetic retinopathy | 7 | 9 |

| Baseline colonic transit | ||

| GC24 | 1.98±0.16 | 1.96±0.18 |

| GC48 | 2.97±0.27 | 2.92±0.22 |

Unless otherwise indicated, values are mean±SEM.

BMI, body mass index; DM, diabetes mellitus; GC24 or GC48, geometric centre for colonic transit at 24 or 48 h; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c.

At baseline, no clinically important differences in gastric emptying, colonic filling at 6 h, and colonic transit were observed for the two treatment groups. Specifically, four patients randomised to placebo and five randomised to pyridostigmine had delayed gastric emptying at baseline, as evidenced by a t1/2 > 90th centile (148 min in men and 160 min in women). Similarly, five in the placebo group and eight in the pyridostigmine group had delayed colonic transit (ie, GC24 <1.7) (table 1).

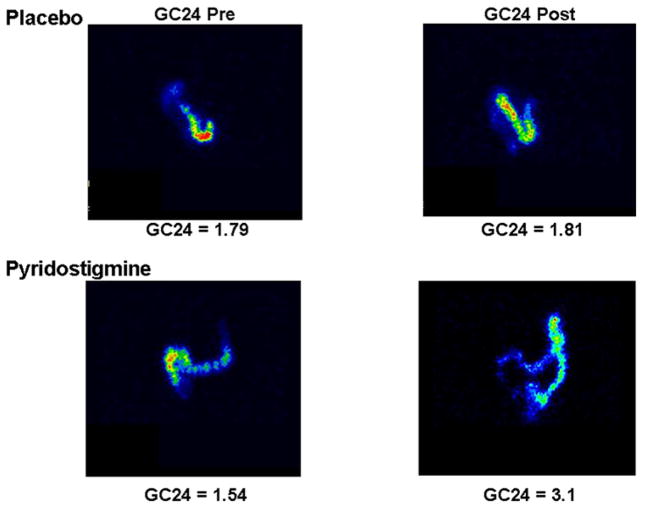

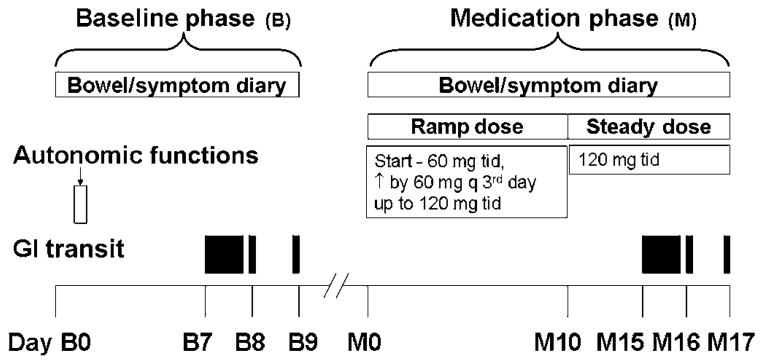

Effects on gastric emptying and small-intestinal and colonic transit

While pyridostigmine accelerated gastric emptying t1/2 and colonic filling at 6 h (%), drug effects were not significant compared with placebo (table 2, figure 3). Pyridostigmine increased the colonic transit GC24 from 1.96±0.18 units at baseline to 2.45±0.2 units during treatment; drug effects were different (p<0.01) relative to placebo (table 2, figures 4 and 5). This difference was significant after adjustment for two comparisons (ie, GC24 and GC48). Among 13 patients with delayed colonic transit (GC24) at baseline, the GC24 normalised in two of five patients treated with placebo and seven of eight patients treated with pyridostigmine. The GC24 increased by 0.6 unit, which is regarded as clinically significant, in six of 15 patients receiving pyridostigmine and one patient treated with placebo.

Table 2.

Effects of pyridostigmine on gastrointestinal transit, bowel symptoms and ECG parameters

| Parameter | Placebo

|

Pyridostigmine

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treatment | Baseline | Treatment | |

| t1/2 for GE (min) | 141±12 | 121±13.42 | 142±19 | 122±13 |

| Colonic filling at 6 h (%) | 41±10 | 48±9 | 37±9 | 53±7 |

| GC24‡ | 1.98±0.17 | 1.84±0.16 | 1.96±0.18 | 2.45±0.20 |

| GC48 | 2.97±0.27 | 3.26±0.27 | 2.92±0.22 | 3.59±0.25 |

| t1/2 for AC emptying (h) | 20.59±3.29 | 18.77±3.23 | 16.73±2.30 | 10.44±1.40 |

| Stool frequency per day (number)† | 1.2±0.2 | 1.4±0.2 | 0.95±0.2 | 1.5±0.2 |

| Stool consistency (BSFS 1–7)§ | 2.8±0.5 | 2.6±0.4 | 2.5±0.3 | 3.4±0.2 |

| Ease of passage (scale 1–7)* | 3.6±0.2 | 3.5±0.2 | 3.5±0.2 | 3.8±0.5 |

| Incomplete evacuation (% bowel movements) | 74±8 | 66±8 | 86±6 | 73±8 |

| Complete spontaneous bowel movements/week | 2.1±0.8 | 3.1±0.9 | 2.1±0.9 | 4.0±1.2 |

| Heart rate/min | 76±4 | 75±3 | 74±3 | 66±2 |

| QTc interval (ms) | 420±8 | 421±4 | 428±6 | 415±18 |

Values are mean±SEM.

p<0.04,

p=0.02,

p<0.01,

p=0.005, for pyridostigmine (during – before treatment) versus placebo (during – before treatment).

AC, ascending colon; BSFS, Bristol Stool Form Scale; GC24 or GC48, geometric centre for colonic transit at 24 or 48 h; GE, gastric emptying.

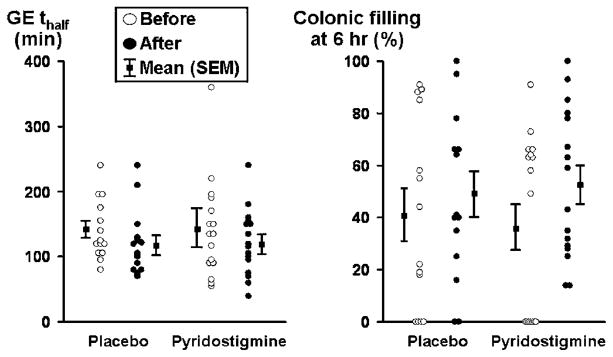

Figure 3.

Effects of pyridostigmine on gastric emptying (GE) and small intestinal transit in diabetes mellitus and constipation. While the gastric emptying half time was shorter after pyridostigmine, differences versus placebo were not significant.

Figure 4.

Effects of pyridostigmine on colonic transit in diabetes mellitus and constipation. Pyridostigmine accelerated (p<0.01) GC24 (geometric centre for colonic transit at 24 h) relative to placebo.

Figure 5.

Scintigraphic images comparing colonic transit before (GC24 (geometric centre for colonic transit at 24 h) Pre) and after (GC24 Post) placebo or pyridostigmine in diabetes mellitus and constipation.

Treatment effects on GC48 were not significant (p=0.096), probably because of a type II error. The ascending colonic emptying t1/2 after treatment was also shorter (p=0.02) for pyridostigmine; however, after adjustment for baseline values, treatment effects were not significantly different compared with placebo.

There were no significant differences between fasting blood glucose concentrations on day 1 of the pre- and post-treatment transit studies. For placebo, blood glucose concentrations were 179±21 mg/dl during the pretreatment study and 177±17 mg/dl during the post-treatment study. For pyridostigmine, corresponding values were 200±20 mg/dl and 184±18 mg/dl, respectively. Similarly, blood glucose concentrations concurrent with 24 and 48 h scans were not significantly different between baseline and medication phases (data not shown).

Influence of presence of autonomic neuropathy on treatment effects

In the pyridostigmine group, treatment effects for GC24 were somewhat larger in patients with (1.6 (mean baseline) vs 2.5 (mean treatment)) than without (2.1 (mean baseline) vs 2.4 (mean treatment)) autonomic neuropathy; however, the interaction term was not significant (p>0.15).

Effects of treatment on bowel functions

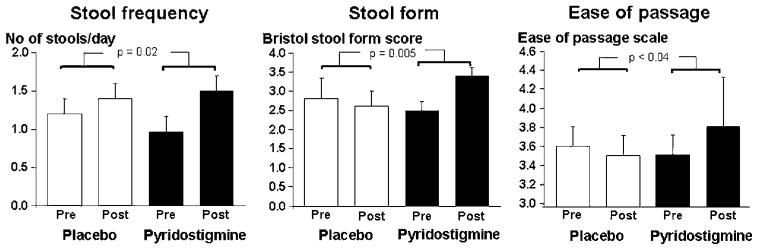

Compared with placebo, pyridostigmine increased stool frequency (p=0.02), decreased stool consistency (p=0.005), and improved ease of stool passage (p<0.04) (figure 6, table 2). The proportions of bowel movements associated with sense of incomplete evacuation declined modestly (<10%) with both treatments and were not significantly different.

Figure 6.

Effects of pyridostigmine on bowel symptoms in diabetes mellitus and constipation. Pyridostigmine improved stool frequency, consistency and ease of passage compared with placebo.

The number of weekly complete spontaneous bowel movements (CSBMs) increased to a greater extent after pyridostigmine (2.1±0.9 (baseline), 4.0±1.2 (treatment)) than after placebo (2.1±0.8 (baseline), 3.1±0.9 (treatment)); the on-treatment numbers of weekly CSBMs (with baseline number as covariate) were not significant, but the increase of 1 CSBM per week on pyridostigmine treatment compared with placebo is clinically relevant. There was a significant correlation between treatment-associated change in stool frequency and GC48 (rs=0.41, p=0.025).

Side effects of pyridostigmine

Fourteen of 16 patients randomised to pyridostigmine reached the maximum dose of 360 mg daily, and two patients reached the ‘entry’ dose of 180 mg daily. There were no serious adverse events (AEs), and no patient had to stop treatment because of an AE. Recorded AEs occurring in more than one patient are shown in table 3. There were no differences detected among the treatment groups in the proportions of subjects with any AEs (p=0.14, Fisher exact test). Side effects predominantly reflected the expected cholinergic actions of pyridostigmine, including lower heart rate (mean change 8/min for pyridostigmine compared with 1/min for placebo, p=0.06) and QTc on ECG (mean −13 ms for pyridostigmine, and +1 ms for placebo (p=ns)) (table 3). Use of rescue agents as permitted for constipation included bisacodyl suppositories (two subjects) and sodium phosphate enemas (four patients); specifically, these patients used enemas on 1 day (two patients), 2 days (one patient) or 3 days (one patient) during the study.

Table 3.

Adverse effects recorded in the entire study population

| Side effect | Placebo (n=14) | Pyridostigmine (n=16) |

|---|---|---|

| None | 9 | 5 |

| Increased salivation and/or sweating | 2 | 3 |

| Muscle twitching | 1 | 3 |

| Gastrointestinal (abdominal discomfort, nausea) | 2 | 4 |

| Fatigue, lightheadedness | 0 | 2 |

| Other/unrelated (pruritus, bluish discoloration of urine, cellulitis) | 0 | 3 |

DISCUSSION

In this controlled therapeutic study, the cholinesterase inhibitor, pyridostigmine, accelerated colonic transit and increased stool frequency, consistency and ease of evacuation in patients with DM and chronic constipation. While the symptomatic observations need to be confirmed by larger studies preferably comparing pyridostigmine with other osmotic stimulant laxatives (eg, bisacodyl) Kamm, 2011 #1632),32 the data suggest that pyridostigmine may be useful for managing constipation in DM.

Pyridostigmine accelerated colonic transit (GC24) by an average of 0.5 unit. This increase is comparable to the acceleration of colonic transit induced by the secretagogue, linaclotide (mean GC24 increase of 0.4 unit), and serotonin 5-HT4 agonists (tegaserod (mean GC24 increase of 0.4 unit) and renzapride (mean GC24 increase of 0.6 unit)) in chronic constipation or IBS-C.24–26 In contrast, lubiprostone did not accelerate colonic transit in IBS.33 Pyridostigimine loosened stool consistency by an average of 0.8 unit on the Bristol Stool Form Scale, which is comparable to the observed 0.9-unit change with renzapride, but smaller than the increment with linaclotide, which is a secretagogue.25,26 Nonetheless, the reduction in stool consistency was sufficient to improve the ease of passage. It is important to note that the sample size was based on the pharmacodynamic end point rather than symptoms. Thus the weekly increase in CSBMs was not statistically significant; however, the increase of 1 CSBM per week relative to placebo is clinically relevant, but smaller than the corresponding mean difference with prucalopride treatment for chronic constipation (ie, 1.4 CSBM for 2 mg and 1.8 CSBM for 4 mg).34

Similarly to previous studies, patients had a spectrum of complications of DM, type and severity of autonomic dysfunctions, and disturbances of GI and colonic transit.9,31,35,36 In this study using a potential colokinetic, patients with defaecatory disorders, which can also occur in DM, were excluded.31 At baseline, 43% of patients had delayed colonic transit, which suggests colonic motor dysfunction, and 57% had normal transit constipation. This is not surprising, since many patients had dominant adrenergic autonomic neuropathy rather than evidence of parasympathetic denervation; adrenergic failure would not be expected to cause slow transit. The mechanism of constipation in these patients is unknown; similarly to the stomach and small intestine, intrinsic motor dysfunction due to loss of nerves and/or loss of interstitial cells of Cajal may also (ie, in addition to autonomic neuropathy) contribute to colonic motor dysfunction.37,38 Because idiopathic chronic constipation is a common symptom, we cannot exclude the possibility that constipation was partly due to medication or otherwise unrelated to DM in some patients. However, all patients reported that the symptoms of constipation began or worsened after the diagnosis of DM, and the proportion of patients with slow colonic transit (43%) is about twice the observed proportion in patients with IBS-C or functional constipation.39,40

Nearly two-thirds of the patients with diabetes randomised in our study had moderate-severe autonomic dysfunctions affecting one or more components of the autonomic nervous system, which is very similar to the prevalence of autonomic dysfunction in a cohort of patients with DM and upper GI motility disorders previously reported.35 In patients with an autonomic neuropathy and constipation, the acute effects of intravenous neostigmine on colonic transit and separately on colonic motility predicted the effect of oral pyridostigmine on colonic transit, suggesting that cholinesterase inhibitors accelerate colonic transit by their colonic motor effects.13 In the present study, the effects of pyridostigmine on colonic transit were more pronounced in patients with than without an autonomic neuropathy; however, differences were not significant, probably because of a type II error. It is important to note that the study was not powered to address the impact of autonomic dysfunction on the effects of treatment on colonic transit. If confirmed, these observations would be consistent with the concept of denervation sensitivity resulting from extrinsic denervation. Pyridostigmine also improves orthostatic intolerance, which is a manifestation of autonomic insufficiency in DM.20

Neostigmine has several other effects on GI function: it increased gastric fundic phasic contractility in humans41 and also improved gastric fundic responses to neural stimulation in Sl/Sl(d) mice, which lack intramuscular interstitial cells of Cajal.42 The cholinesterase inhibitor, acotiamide, increased gastric antral and colonic motor activity at similar doses in dogs.43 If true for pyridostigmine, it seems unlikely that a higher pyridostigmine dose is required to increase antral than colonic motor activity. In this study, gastric emptying was faster after treatment in both groups (placebo and pyridostigmine); hence differences were not significant. Another possibility is that pyridostigmine increased both gastric antral and duodenal phasic contractility; hence the pressure gradient necessary for gastric emptying did not increase.

While hyperglycaemia may contribute to colonic motor dysfunction in DM, the effects of acute hyperglycaemia on colonic sensorimotor functions are variable and relatively modest.44,45 Moreover, the mean fasting blood glucose concentration before the start of the transit study was 190 mg/dl, which is lower than the concentration (270 mg/dl) in studies evaluating the effect of acute hyperglycaemia on colonic sensorimotor functions. Hence, it is unlikely that delayed colonic transit in this study was primarily attributable to hyperglycaemia. Finally, since blood glucose concentrations were not significantly different between baseline and medication phase transit studies, the pyridostigmine-induced acceleration in colonic transit cannot be attributed to improved glycaemic control.

Fourteen of 16 patients who were randomised to pyridostigmine tolerated the maximum dose of 360 mg daily. This dose was higher than the dose used to treat orthostatic hypotension in patients with autonomic neuropathy,20,46 but lower than the maximum dose in our previous uncontrolled study (ie, 540 mg daily) and the maximum recommended dose of 120 mg every 3 h.47 Cholinergic side effects were generally modest in severity and no clinically significant cardiovascular side effects were observed. Muscarinic actions were the most common side effect in myasthenia gravis, and GI symptoms were the most common complaint.48 Moreover, in that study, the presence of daily muscarinic effects correlated with baseline cholinesterase activity, which in turn was related to the dose of pyridostigmine, and more pronounced for doses higher than 400 mg daily. In patients who do not respond to a dose less than 360 mg daily, a higher dose can be considered, but may be associated with other muscarinic and nicotinic side effects.

It has been suggested that exposure to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors contributes to illness in Gulf-War veterans, manifested as multiple or at least moderately severe symptoms in three or more of six symptom groups: fatigue/sleep, pain, neurological/cognitive/mood, and GI, respiratory and skin problems.49 In animals, exposure to acetylcholinesterase inhibitors alters regulation of cholinergic function, which affects domains affected in Gulf-War veterans (eg, muscle function, cognition). Illness was more likely in veterans who had low concentrations and activity levels of enzymes (eg, butyrylcholinesterase) that clear acetyl-cholinesterase inhibitors. However, these findings have not affected the use of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors for managing myasthenia gravis.

In summary, these observations suggest that pyridostigmine improves bowel symptoms and accelerates colonic transit in patients with DM and constipation. If confirmed in larger studies of longer duration, they may provide a new approach for managing this understudied, underappreciated and sometimes refractory symptom.

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

-

Constipation in diabetes mellitus

is managed with laxatives, but there are no controlled clinical trials

may be attributable to extrinsic or enteric neuropathy.

Cholinesterase inhibitors increase gastrointestinal motility and cause diarrhoea.

What are the new findings?

Pyridostigmine, which is a cholinesterase inhibitor, accelerated colonic transit and improved bowel symptoms in diabetic patients with constipation.

Pyridostigmine was well tolerated; cholinergic side effects were more common with pyridostigmine than with placebo.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

While the data need to be confirmed by larger studies, pyridostigmine may be a useful treatment for diabetic patients with constipation, particularly as it also improves orthostatic hypotension in this disorder.

Acknowledgments

Funding This study was supported by USPHS NIH Grant P01 DK068055 and UL1 RR024150-01* from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. PL’s contribution was supported in part by the NIH (NS 44233). The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Reengineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00276406

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

Ethics approval The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

Contributors AEB: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, important intellectual content, statistical analysis, obtained funding, technical or material support, study supervision. PAL and MC: critical revision of the manuscript, important intellectual content. EV: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis. DB: acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript, technical or material support. YK and PS: critical revision of the manuscript, technical or material support. TLG: acquisition of data, critical revision of the manuscript. ARZ: drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript, statistical analysis.

References

- 1.Janatuinen E, Pikkarainen P, Laakso M, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms in middle-aged diabetic patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1993;28:427–32. doi: 10.3109/00365529309098244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maleki D, Locke GR, 3rd, Camilleri M, et al. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms among persons with diabetes mellitus in the community. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2808–16. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Hammer J, et al. GI symptoms in diabetes mellitus are associated with both poor glycemic control and diabetic complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:604–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasler WL, Coleski R, Chey WD, et al. Differences in intragastric pH in diabetic vs. idiopathic gastroparesis: relation to degree of gastric retention. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1384–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00023.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buysschaert M, Donckier J, Dive A, et al. Gastric acid and pancreatic polypeptide responses to sham feeding are impaired in diabetic subjects with autonomic neuropathy. Diabetes. 1985;34:1181–5. doi: 10.2337/diab.34.11.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caruana BJ, Wald A, Hinds JP, et al. Anorectal sensory and motor function in neurogenic fecal incontinence. Comparison between multiple sclerosis and diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:465–70. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90217-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashyap P, Farrugia G. Diabetic gastroparesis: what we have learned and had to unlearn in the past 5 years. Gut. 2010;59:1716–26. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.199703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Law NM, Bharucha AE, Undale AS, et al. Cholinergic stimulation enhances colonic motor activity, transit, and sensation in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1228–37. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.281.5.G1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Battle WM, Snape WJ, Jr, Alavi A, et al. Colonic dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:1217–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ponec RJ, Saunders MD, Kimmey MB. Neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:137–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907153410301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadjadpour K. Pyridostigmine bromide and constipation in Parkinson’s disease. JAMA. 1983;249:1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasha SF, Lunsford TN, Lennon VA. Autoimmune gastrointestinal dysmotility treated successfully with pyridostigmine. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1592–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bharucha AE, Low PA, Camilleri M, et al. Pilot study of pyridostigmine in constipated patients with autonomic neuropathy. Clin Auton Res. 2008;18:194–202. doi: 10.1007/s10286-008-0476-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Osinski MA, Bass P. Chronic denervation of rat jejunum results in cholinergic supersensitivity due to reduction of cholinesterase activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:1684–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inoue T, Okasora T, Okamoto E. Effect on muscarinic acetylcholine receptors after experimental neuronal ablation in rat colon. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:G940–4. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.6.G940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leelakusolvong S, Bharucha AE, Sarr MG, et al. Effect of extrinsic denervation on muscarinic neurotransmission in the canine ileocolonic region. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:173–86. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2003.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trojan DA, Collet JP, Shapiro S, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blinded trial of pyridostigmine in postpolio syndrome. Neurology. 1999;53:1225–33. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45:1143–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bharucha AE, Wald AM. Anorectal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:786–94. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Low PA, Singer W. Management of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension: an update. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:451–8. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70088-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cremonini F, Mullan BP, Camilleri M, et al. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic transit measurements for studies of experimental therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1781–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bharucha AE, Ravi K, Zinsmeister AR. Comparison of selective M3 and nonselective muscarinic receptor antagonists on gastrointestinal transit and bowel habits in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G215–19. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00072.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deiteren A, Camilleri M, Bharucha AE, et al. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic colon transit measurement in health and irritable bowel syndrome and relationship to bowel functions. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:415–23. e95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prather CM, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Tegaserod accelerates orocecal transit in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:463–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Camilleri M, McKinzie S, Fox J, et al. Effect of renzapride on transit in constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:895–904. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andresen V, Camilleri M, Busciglio IA, et al. Effect of 5 days linaclotide on transit and bowel function in females with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:761–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intestinal transit time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:920–4. doi: 10.3109/00365529709011203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Low PA. Autonomic nervous system function. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;10:14–27. doi: 10.1097/00004691-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Low PA. Composite autonomic scoring scale for laboratory quantification of generalized autonomic failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:748–52. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Low PA, Denq JC, Opfer-Gehrking TL, et al. Effect of age and gender on sudomotor and cardiovagal function and blood pressure response to tilt in normal subjects. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:1561–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4598(199712)20:12<1561::aid-mus11>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maleki D, Camilleri M, Burton DD, et al. Pilot study of pathophysiology of constipation among community diabetics. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:2373–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1026657426396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Camilleri M, Bharucha AE. Behavioural and new pharmacological treatments for constipation: getting the balance right. Gut. 2010;59:1288–96. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.199653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Gangarosa L, et al. Lubiprostone does not influence visceral pain thresholds in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:944–e400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01776.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Camilleri M, Kerstens R, Rykx A, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of prucalopride for severe chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2344–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bharucha AE, Camilleri M, Low PA, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in gastrointestinal motility disorders. Gut. 1993;34:397–401. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung H-K, Kim D-Y, Moon I-H, et al. Colonic transit time in diabetic patients—comparison with healthy subjects and the effect of autonomic neuropathy. Yonsei Med J. 2003;44:265–72. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2003.44.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He CL, Soffer EE, Ferris CD, et al. Loss of interstitial cells of cajal and inhibitory innervation in insulin-dependent diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:427–34. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.26264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakahara M, Isozaki K, Hirota S, et al. Deficiency of KIT-positive cells in the colon of patients with diabetes mellitus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:666–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Camilleri M, McKinzie S, Busciglio I, et al. Prospective study of motor, sensory, psychologic, and autonomic functions in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:772–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.02.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manabe N, Wong BS, Camilleri M, et al. Lower functional gastrointestinal disorders: evidence of abnormal colonic transit in a 287 patient cohort. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:293–e82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01442.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Stefano M, Vos R, Klersy C, et al. Neostigmine-induced postprandial phasic contractility in the proximal stomach and dyspepsia-like symptoms in healthy volunteers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2797–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beckett EAH, Horiguchi K, Khoyi M, et al. Loss of enteric motor neurotransmission in the gastric fundus of Sl/Sl(d) mice. J Physiol. 2002;543:871–87. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.021915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nagahama K, Matsunaga Y, Kawachi M, et al. Acotiamide, a new orally active acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, stimulated gastrointestinal motor activity in conscious dogs. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01912.x. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maleki D, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Effect of acute hyperglycemia on colorectal motor and sensory function in humans. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G859–64. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.4.G859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sims MA, Hasler WL, Chey WD, et al. Hyperglycemia inhibits mechanoreceptor-mediated gastrocolonic responses and colonic peristaltic reflexes in healthy humans. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:350–9. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singer W, Opfer-Gehrking TL, McPhee BR, et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibition: a novel approach in the treatment of neurogenic orthostatic hypotension. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1294–8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daube JMrF. Clinical Neurophysiology of Disorders of Muscle and Neuromuscular Junction, Including Fatigue. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Punga AR, Sawada M, Stalberg EV. Electrophysiological signs and the prevalence of adverse effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors in patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:300–7. doi: 10.1002/mus.20935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Golomb BA. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and Gulf War illnesses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4295–300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711986105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]