Abstract

Midkine (MK) is a heparin-binding growth factor or cytokine and forms a small protein family, the other member of which is pleiotrophin. MK enhances survival, migration, cytokine expression, differentiation and other activities of target cells. MK is involved in various physiological processes, such as development, reproduction and repair, and also plays important roles in the pathogenesis of inflammatory and malignant diseases. MK is largely composed of two domains, namely a more N-terminally located N-domain and a more C-terminally located C-domain. Both domains are basically composed of three antiparallel β-sheets. In addition, there are short tails in the N-terminal and C-terminal sides and a hinge connecting the two domains. Several membrane proteins have been identified as MK receptors: receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase Z1 (PTPζ), low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein, integrins, neuroglycan C, anaplastic lymphoma kinase and Notch-2. Among them, the most established one is PTPζ. It is a transmembrane tyrosine phophatase with chondroitin sulfate, which is essential for high-affinity binding with MK. PI3K and MAPK play important roles in the downstream signalling system of MK, while transcription factors affected by MK signalling include NF-κB, Hes-1 and STATs. Because of the involvement of MK in various physiological and pathological processes, MK itself as well as pharmaceuticals targeting MK and its signalling system are expected to be valuable for the treatment of numerous diseases.

Linked Articles

This article is part of a themed section on Midkine. To view the other articles in this section visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bph.2014.171.issue-4

Keywords: anaplastic lymphoma kinase, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1, midkine, Notch-2, pleiotrophin, receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase Z1

Introduction

Growth factors and/or cytokines play fundamental roles in the regulation of cellular activities and in various pathological processes. One such key factor with increasing importance is midkine (MK), which is a heparin-binding growth factor or cytokine (Erguven et al., 2012). MK was found as the product of a gene up-regulated at an early stage of retinoic acid-induced differentiation of teratocarcinoma stem cells (Kadomatsu et al., 1988) and became the founding member of a small protein family, the other member of which is pleiotrophin (PTN), also called heparin-binding growth-associated molecule (Milner et al., 1989; Rauvala, 1989; Tomomura et al., 1990; Muramatsu, 2010).

MK is involved in various physiological processes, such as development, reproduction and repair (Erguven et al., 2012). Furthermore, MK plays important roles in the aetiology of inflammatory and malignant diseases (Erguven et al., 2012). Therefore, MK itself and the reagents targeting MK are expected to be valuable for the treatment of diverse diseases, as covered in this special issue. The purpose of this article is to provide concise and up-to-date information on the structure, physiological activities and signalling of MK as a basis to understand the pharmacological effects of MK and its antagonists.

In addition to articles in this special issue, readers are also referred to a book (Erguven et al., 2012) and other review articles on MK (Muramatsu, 2002; 2010;2011; Kadomatsu and Muramatsu, 2004; Weckbach et al., 2011; Kadomatsu et al., 2013). In particular, there is a recent article on drug development in relation to MK (Muramatsu, 2011) and a comprehensive review on circulating MK in patients with various diseases (Krzystek-Korpacka and Matusiewicz, 2012). Furthermore, it is appropriate to mention that occasionally citations in this introductory article refer to a review article citing the original articles in order to keep the number of references to a moderate level.

MK protein

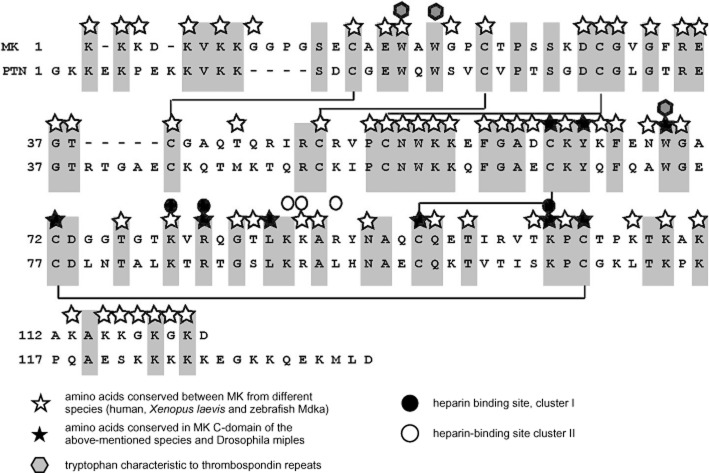

MK is rich in both basic amino acids and cysteine. Human MK is composed of 121 amino acids with a molecular mass of 13 kDa after cleaving off the signal sequence (Tsutsui et al., 1991) (Figure 1). An isoform with two extended amino acids (valine-alanine or other amino acids) at the N-terminal is present in MK preparations from different species due to a difference in the cleavage of the signal sequence (Raulais et al., 1991; Muramatsu et al., 1993; Novotny et al., 2013; Ohyama et al., 1994). This point is described in more detail at the end of this section in relation to the production of MK for pharmaceutical purposes.

Figure 1.

Structure of human MK and PTN. Amino acids shared by them are shaded, and disulfide bridges are shown by solid lines.

No phosphorylation or glycosylation has been detected so far in MK protein produced by baculovirus (Kaneda et al., b1996) or human hepatoma cells (M. Oda et al., unpubl. data).

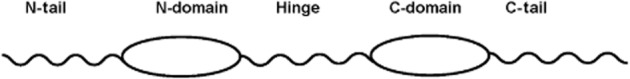

Disulfide linkages form two domains in the MK molecule, the more N-terminally located N-domain (amino acids 15–52) and the more C-terminally located C-domain (amino acids 62–104) (Fabri et al., 1993) (Figure 2). N-domain is held by three disulfide bridges, while C-domain by two disulfide bridges. In addition, there are short tails in the N-terminal region (amino acids 1–14) and the C-terminal region (amino acids 105–121), called N-tail and C-tail respectively. A hinge (amino acids 53–61) connects N-domain and C-domain (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic drawing of MK and its segments.

MK and PTN have about 50% sequence identity, cysteine and tryptophan residues being conserved between human MK and PTN (Figure 1). MK and PTN are found in all species of vertebrates so far examined (Muramatsu, 2002; 2010). Zebrafish have two different molecular species of MK called Midkine-a (Mdka) and Midkine-b (Mdkb), which are likely to be generated by gene duplication (Winkler et al., 2003). Many amino acid residues in MK are conserved between species. Human and mouse MK have 87% identity (Tsutsui et al., 1991), and 55% of amino acids are identical in MK from human, Xenopus laevis and zebrafish Mdka (Svensson et al., 2010) (Figure 1). Interestingly, a high degree of conservation is observed in the hinge region. Drosophila melanogaster lacks MK or PTN but has two molecules called miple (miple-1) and miple-2, which have duplicated domains resembling C-domains of MK and PTN (Englund et al., 2006). A mollusc, Patella caerulea, also has a related molecule (Vanucci et al., 2005). Amino acids characteristically conserved in the C-domain of MK and miples (Figure 1) are mostly conserved in the MK-like protein from P. caerulea. An MK-related protein has not been described in Caenorhabditis elegans. It is an interesting subject to pinpoint the evolutional event associated with the emergence of an MK-related protein.

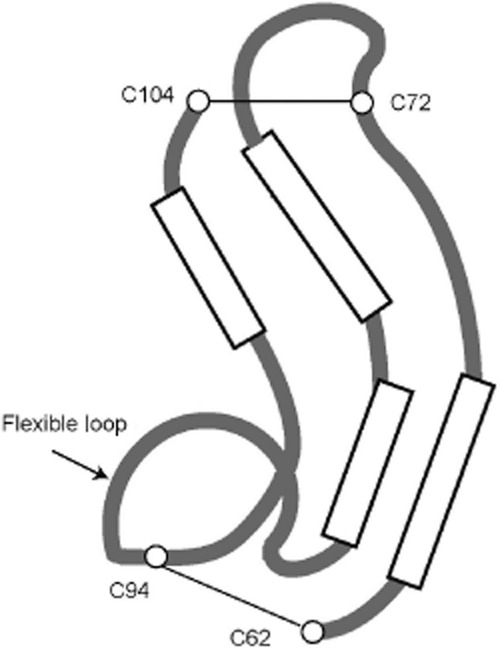

The three-dimensional structure of human MK has been studied by NMR spectroscopy (Iwasaki et al., 1997). Analysis of the spectrum of the whole molecule suggested that the two domains are relatively independent of each other because no specific interactions are detectable between them. Furthermore, it has been shown that the two tails do not have stable structures. Then, the structure of N-domain and C-domain has been clarified by using the N-terminal half molecule and truncated C-terminal half molecule (Iwasaki et al., 1997). The half molecule consists of the tail, domain and a part of the hinge. Both N-and C-domains are basically composed of three antiparallel β-sheets. The structure of C-domain is more complex than that of N-domain. In particular, there is a flexible loop in the middle of the C-domain (amino acids 86–93), and a pocket is created in the domain (Figure 3). Recently, detailed analysis of the whole molecule of zebrafish Mdkb has been performed and has revealed the whole structure of MK, including the hinge region, which has an extended structure (Lim et al., 2013).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the steric structure of MK C-domain. Long boxes are emphasized portions of β-sheets as illustrated in the protein structure database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/structure/mn).

Both domains of MK and the corresponding domains of PTN have weak homology to thrombospondin type-1 repeats, which are present in thrombospondin-1, F-spondin and many other proteins, including circumsporozoite protein from malaria paracytes (Kilpelainen et al., 2000). Thrombospondin type-1 repeats are composed of three antiparallel β-sheets, which are generally held by three disulfide bridges (Tan et al., 2002). In this respect, N-domains of MK and PTN are more closely related to thrombospondin type-1 repeats as compared with the C-domains, which are held by two disulfide bridges. Furthermore, domains of MK and PTN, especially N-domains, are truncated. Consequently, domains of MK and PTN lack the core structure of thrombospondin repeats, namely a CWR-layered structure, which has repeated tryptophan and arginine arrangements sandwiched by cysteine, and contributes to the stability of thrombospondin repeats (Tan et al., 2002). Two tryptophan residues, which are located in the first β-sheets of thrombospondin type-1 repeats, are present in the N-domain of human MK and PTN (closed hexagon, Figure 1). However, W20 in human MK is not conserved throughout MK of different species. Furthermore, only one such tryptophan residue is present in the C-domain of MK and PTN (Figure 1). As above, MK and PTN domains are only distantly related to thrombospondin type-1 repeats.

The evolutional origin of the two domains in MK remains to be clarified. Considering the structural resemblance of the N-and C-domains, it is reasonable to consider that a primordial molecule common to MK and PTN emerged by intra chromosome duplication of a primordial gene encoding the primordial domain, and then the two proteins, MK and PTN, emerged as the result of duplication of a segment of a chromosome. From the homology to thrombospondin type-1 repeats, N-and C-domains can be considered to have evolved independently from the primordial domain related to thrombospondin repeats, while the presence of Drosophila miples is consistent with the view that the C-domain is more related to the primordial domain.

Among the two domains, C-domain has been considered to play more important roles in MK function as neurite-promoting activity of MK is observed in the C-terminal half molecule, and to a lesser extent, also by the C-domain (Muramatsu et al., 1994; Akhter et al., 1998). Furthermore, an MK receptor, receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase Z1 (PTPζ), binds to the C-terminal half but not to the N-terminal half (Maeda et al., 1999). Two heparin-binding sites are present in the C-domain of human MK. The site present in β-sheets called cluster 1 (K79, R81, K102) (Iwasaki et al., 1997) is conserved in MK of different species and also in PTN (closed circle, Figure 1). The other site in the flexible loop called cluster 2 (K86, K87, R89) is conserved only partly (open circle, Figure 1). However, in zebrafish Mdkb, which has only two basic amino acids in cluster 2, the cluster still functions as a heparin-binding site (Lim et al., 2013). Cluster 1 appears to be important not only to heparin binding but also to MK function because a mutation in cluster 1 reduces neurite-promoting activity (Asai et al., 1997) and binding to PTPζ (Maeda et al., 1999).

N-domain has functions different from those of C-domain. Firstly, another heparin-binding site has been identified in the N-domain of Mdkb (Lim et al., 2013). The key residue of the new binding site is R36, corresponding to R35 in human MK (Lim et al., 2013). Secondly, K46/K48 in Mdkb, which corresponds to R45/R47 in human MK, is required for perturbation of zebrafish embryogenesis upon Mdkb injection into the embryos at the blastocyst stage (Lim et al., 2013).

Furthermore, N-domain appears to be important for the stability of MK as the C-terminal half of MK is more susceptible to chymotrypsin digestion than intact MK (Matsuda et al., 1996). N-domain is also involved in dimerization. MK forms a dimer by spontaneous association, and the dimer is stabilized via cross linking by transglutaminase (Kojima et al., 1997). Dimerization is essential for some MK activity, such as activation of fibrinolytic activity by endothelial cells. Q42 or Q44 in N-domain and Q95 in C-domain serve as amine acceptors in the reaction. A peptide fragment, A41-P51, containing the amine acceptor site inhibits MK activity for activation of fibrinolysis (Kojima et al., 1997).

N-tail and C-tail appear to function to keep the two domains independent based on the following observation. Although removal of either tail from intact MK strongly suppresses neurite-promoting activity, isolated C-domain retains a moderate level of activity (Akhter et al., 1998). However, bacteriocidal activity is observed in a peptide containing C-tail and another peptide containing part of the hinge and N-domain (Svensson et al., 2010).

The conserved hinge is likely to have functions other than domain orientation as a mutant Mdkb called MdkbG, in which the hinge is exchanged with oligo-glycine, exhibits the overall structure indistinguishable from that of wild-type Mdkb (Lim et al., 2013). Indeed, another new heparin-binding site has been found in the hinge. The binding site consists of K56 and K57, corresponding to K55 and K56 in human MK (Lim et al., 2013). Furthermore, upon injection into zebrafish embryos, MdkbG mutant exhibits abnormality different from that observed upon injection with wild-type Mdkb (Lim et al., 2013).

MK proteins have been produced by various means and even chemically synthesized (Muramatsu, 2010; 2011). The choice of organisms to produce recombinant MK has been reviewed, and the most important aspect is to avoid the formation of aberrant disulfide linkages (Muramatsu, 2011). In addition, practical information for handling MK protein has been described (Muramatsu et al., 2003; Muramatsu, 2011). Notably, it is important to prevent from MK sticking to the vessel.

Finally, to produce MK with a longer half-life, the extended form, which has a VA extended sequence on the N-terminal side due to differential cleavage of the signal sequence, is of significant interest. In mouse MK produced by L cells and purified by heparin-agarose column chromatography, 5% is the VA extended isoform, and the rest is the conventional form (Muramatsu et al., 1993), while heparin-released MK in human plasma is the VA extended form (Novotny et al., 2013). In MK purified from bovine follicular fluid, 30% is the extended form, and the rest is the conventional form (Ohyama et al., 1994). Chicken MK called RI-HB (retinoic acid-induced heparin-binding protein) purified from chicken embryo is the corresponding alanine-lysine extended form (Raulais et al., 1991).

Oda et al. separated the two isoforms produced by human hepatoma cells using a poly-sulfoethyl A column (M. Oda et al., unpublished results). About 60% was the extended form, and the rest was the conventional form. The extended form bound to heparin more weakly and was more resistant to chymotrypsin digestion, while no difference was found in neurite-promoting activity. They also developed a specific immunoassay procedure to detect the extended form and found that the extended form was more readily released into blood by heparin administration and stayed longer in blood, probably due to less affinity to heparin and relative resistance to protease. Their result is consistent with the finding of Novotny et al. (2013). In sera from cancer patients, the conventional form was always detected, and the extended form was detected in restricted cases, while in amniotic fluid, the extended form was found in most cases (M. Oda et al., unpubl. data). Thus, the VA extended form constitutes a significant portion of naturally occurring MK in humans. Although chymotrypsin cleaves MK only at the hinge region (Matsuda et al., 1996), alteration of interactions of the N-and C-domains due to VA extension is expected to result in chymotrypsin resistance. The same consideration is applicable to the weaker heparin-binding activity of the extended form. The relative resistance of the extended form to proteolysis is of significant interest, and further alteration in the N-terminal sequence might be attempted to create MK with a longer half-life.

MK gene

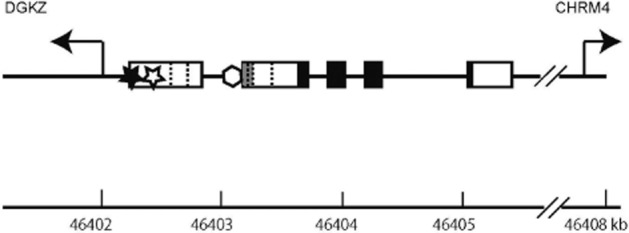

The human MK gene (MDK) is located on chromosome 11 at p11.2 (Kaname et al., 1993) and is flanked by the diacylglycerol kinase ζ gene and the muscarinic cholinergic receptor 4 gene (Muramatsu, 2002). MDK has four coding exons (Figure 4). Due to differential splicing and differences in the transcription initiation site, there are seven isoforms in MK mRNA. Five different non-coding sequences are present in the 5′ ends of the isoforms. Two isoforms are generated by skipping a coding exon and yield truncated MK. A truncated MK derived from mRNA without the second coding exon is apparently tumour-specific and might be of diagnostic value (Kaname et al., 1996; Paul et al., 2001; Muramatsu, 2010).

Figure 4.

Genomic organization of the human midkine gene (MDK). Coding exons are shown by closed boxes, and non-coding exons are shown by open or grey boxes. There are five different structures in the upstream non-coding exons in MK mRNA. When a portion of an exon is shared by different structures, the boundaries are shown by dotted vertical lines. The full information on all MK mRNA isoforms is available (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/4192). The first exon shared by three isoforms is shown by a grey box. DGKZ, diacylglycerol kinase ζ gene; CHRM4, muscarinic cholinergic receptor 4 gene; closed star, a retinoic acid responsive element; open star, a binding site for NF-κB; open hexagon, a binding site for the product of Wilms' tumour suppressor gene.

In the promoter region of MDK, there are functional binding sites for retinoic acid receptor (Pedraza et al., 1995) (closed star, Figure 4) and for the product of Wilms' tumour suppressor gene (Adachi et al., 1996) (open hexagon, Figure 4). They are regarded to be important for retinoic acid-induced expression of MK and up-regulation of MK in Wilms' tumour cells respectively. There is also a hypoxia responsible element in the promoter region; this element is expected to be involved in the induction of MK upon ischaemia and possibly in the increased expression of MK in various tumours (Reynolds et al., 2004). A binding site for NF-κB in the promoter region (Uehara et al., 1992) (open star, Figure 4) might participate in the induction of MK upon inflammation and tumourigenesis.

Glucocorticoid receptor plays a role in the down-regulation of MK expression (Kaplan et al., 2003). In mice deficient in the glucocorticoid receptor, robust expression of MK in the lung is continued in the neonatal stage. Further studies have revealed that glucocorticoids indeed down-regulate MK expression in fetal lung cells (Kaplan et al., 2003). This activity of glucocorticoids is interesting as they are potent anti-inflammatory compounds, and MK is involved in inflammation; MK gene might be a target of glucocorticoids.

Concerning SNP, a variant in an intron is correlated with about a fivefold increase in the risk of colorectal carcinoma (Ahmed et al., 2002). To the best of my knowledge, this is the only SNP with known physiological or pathological impacts. However, it is quite possible that other SNPs, which serve as valuable biomarkers in other diseases, remain to be reported.

Finally, the human PTN gene is very large and is located at a location unrelated to MDK, namely 7q33. However, the number of coding exons, sequences around the intron/exon boundaries and gene families flanking PTN are shared with MDK (Muramatsu, 2002), consistent with the view that both genes evolved from a common ancestral gene (Winkler et al., 2003).

MK in development and reproduction

MK is involved in development, reproduction, repair, inflammation, innate immunity, control of blood pressure and angiogenesis (Erguven et al., 2012). The mode of MK expression is consistent with the view that MK plays a role in both development and repair. Thus, MK is strongly expressed during embryogenesis, especially in the mid-gestation period (Kadomatsu et al., 1990; Mitsiadis et al., 1995b). In adults, significant MK expression is observed only in restricted sites such as the kidney (Kadomatsu et al., 1990), gut (Aridome et al., 1995), epidermis (Inazumi et al., 1997), bronchial epithelium (Nordin et al., 2013), lymphocytes (Cohen et al., 2012) and macrophages (Inoh et al., 2004), while MK expression is induced in many tissues after injury (Yoshida et al., 1995; Obama et al., 1998; Horiba et al., 2000; Sato et al., 2001).

In spite of robust expression of MK in embryos, mice deficient in the MK gene are born without any major morphological defects and reproduce apparently normally (Muramatsu, 2010). The same is true for mice deficient in the PTN gene. However, when mice doubly deficient in both genes are generated by crossing the respective heterozygously deficient mice, they are born only with one-third of the frequency expected by Mendelian segregation (Muramatsu et al., 2006). Furthermore, double-deficient mice are small (Muramatsu et al., 2006) and frequently die before reaching adulthood (H. Muramatsu et al., unpublished observation). MK/PTN double-deficient mice also exhibit severe female infertility. About 80% of double-deficient mice remained infertile even after repeated trials (Muramatsu et al., 2006). The principal reason of the infertility has been concluded to be impaired follicular maturation. MK and PTN expressed in follicular epithelium and granulosa cells in the ovary are considered to be required for follicular maturation. Consistent with this view, MK promotes the maturation of isolated bovine oocytes, and subsequent fertilization and development to blastocysts (Ikeda et al., 2000).

The above results established the importance of the MK/PTN family in development and reproduction, and illustrate that the defect of MK is largely compensated by PTN. This compensation can occur even in tissue with only slight PTN expression, because in some organs, MK suppresses the expression of PTN (Herradon et al., 2005). Thus, in MK-deficient mice, PTN expression is strikingly increased in organs such as the heart, spinal cord, eye and aorta (Herradon et al., 2005).

In addition to defects in development and reproduction, double-deficient mice also exhibit auditory deficit (Zou et al., 2006b; Sone et al., 2011). Although mice deficient in only MK or PTN show an auditory deficit, that in double-deficient mice is severer. The deficit in these mice is considered to be due to a deficit of intermediate cells in the stria vascularis of the cochlear duct (Sone et al., 2011).

The role of MK in development needs a more detailed review. During mouse embryogenesis, MK becomes expressed on embryonic day 5.5 in the embryonic ectoderm (Fan et al., 2000). Consistent with the mode of its expression, MK is expressed in embryonic stem cells, and its role in their survival has been described (Lee et al., 2012).

MK is intensely expressed in the mid-gestation stage, and from the mode of its distribution, MK has been proposed to play roles in neurogenesis, epithelial-mesenchymal interactions and mesoderm remodelling (Kadomatsu et al., 1990).

Concerning neurogenesis, studies using the zebrafish system have revealed that Mdka is involved in the final stage of the fate decision of precursor cells to become either medial floor plate cells constituting the ventral portion of the spinal cord or notochord cells (Schafer et al., 2005). However, Mdkb is required for the development of neural crest cells and sensory neurons (Liedtke and Winkler, 2008). In X. laevis, MK enhances neurogenesis and suppresses mesoderm differentiation in the presence of activin (Yokota et al., 1998). Furthermore, MK appears to be involved in dopaminergic development by enhancing the survival of mesencephalic neurons, and Parkinson-like syndrome is observed in MK-deficient mice (Ohgake et al., 2009; Muramatsu, 2011; Prediger et al., 2011).

In the cerebral cortex of the embryonic rat brain, MK is located in both the basal layer where neural stem cells are located and along radial glial processes, which are derived from the stem cells and serve as guides for the migration of differentiated neurons (Matsumoto et al., 1994). This mode of location is consistent with the multiple roles of MK in neurogenesis. As a basis of MK activity in neurogenesis, MK enhances the growth and survival of neural precursor cells, including neural stem cells (Zou et al., 2006a). MK also promotes the survival, migration and neurite outgrowth of embryonic neurons (Michikawa et al., 1993; Muramatsu et al., 1993; Kaneda et al., b1996; Maeda et al., 1999; Owada et al., 1999; Muramatsu, 2011). In relation to the MK activity to neural precursor cells, MK also enhances growth and survival of primordial germ cells (Shen et al., 2012).

MK is generally more strongly expressed in epithelial tissues than in mesenchymal tissues in embryonic organs where epithelial-mesenchymal interactions are taking place, such as the intestine, pancreas and lung (Kadomatsu et al., 1990; Mitsiadis et al., 1995b). The role of MK in epithelial-mesenchymal interactions has been verified by inhibition of the development of the tooth germ using anti-MK antibodies (Mitsiadis et al., 1995a). The mode of action of MK during epithelial-mesenchymal interactions appears to be complex, as revealed by a study using an artificial blood vessel model, in which collagen gels with smooth muscle cells are covered by endothelial cells (Sumi et al., 2002). In this system, endothelial cells secrete MK, which stimulates smooth muscle cells to secrete IL-8. IL-8 then acts on endothelial cells to promote their growth. Thus, MK is apparently in a central position among the complex interactions of the two cell layers.

Concerning mesoderm remodelling, MK stimulates adipocyte differentiation (Cernkovich et al., 2007), chondrogenesis (Ohta et al., 1999) and osteoclast differentiation (Maruyama et al., 2004), and promotes the differentiation and suppresses the proliferation of osteoblasts (Liedert et al., 2011).

MK in repair and inflammation

MK expression is increased in a number of injured tissues, such as the brain (Yoshida et al., 1995), blood vessels (Horiba et al., 2000), kidney (Sato et al., 2001) and heart (Obama et al., 1998; Horiba et al., 2006). The role of MK in the repair of damaged tissue was demonstrated by the effects of administered MK in reducing light-induced degeneration of the retina (Unoki et al., 1994) and ischaemic brain injury (Yoshida et al., 2001). Then, ischaemic injury of the heart has also been attenuated by MK administration (Horiba et al., 2006). Consistent with the effect of externally administered MK, mice deficient in the MK gene exhibit severer heart damage after ischaemia (Horiba et al., 2006). The basis of this MK activity is anti-apoptotic activity, leading to survival of the affected cells (Horiba et al., 2006).

However, ischaemic injury in the kidney is severer in wild-type mice than in MK-deficient mice (Sato et al., 2001). This is because MK induced by ischaemia recruits inflammatory leukocytes to the injured renal epithelium. In the case of partial hepatectomy, induced MK enhances tissue repair as well as inflammation, and the balance is slightly in favour of repair: the reparative process is slightly more enhanced in wild-type mice than in MK-deficient mice (Ochiai et al., 2004).

In the brain, MK does not appear to play important roles in neuroinflammation because MK does not activate astrocytes or microglias (Muramoto et al., 2013). Generally, MK exerts protective roles in the brain (Muramatsu, 2011). As an example, MK-deficient mice exhibit increased amphetamine-induced astrocytosis (Gramage et al., 2011). Furthermore, MK enhances migration of microglias and is likely to contribute to the clearance of amyloid β-peptide (Muramatsu, 2011).

MK participates in inflammatory processes by exerting two different activities. Firstly, MK enhances the migration of neutrophils and macrophages both by direct action of MK and by inducing chemokine expression (Takada et al., 1997; Horiba et al., 2000; Sato et al., 2001). Secondly, MK suppresses differentiation of regulatory T-cells partly by inhibiting the development of tolerogenic dendric cells, which are essential for the differentiation (Wang et al., 2008; Sonobe et al., 2012). Inflammation, which is enhanced by MK, is part of the immune system. MK also has anti-microbial activities and is regarded as a component of the innate immune system (Svensson et al., 2010; Nordin et al., 2013). Furthermore, MK has been found to enhance the survival of B cells (Cohen et al., 2012). Thus, MK plays diverse roles in counteracting infection upon injury.

MK is also known to have angiogenic activity (Choudhuri et al., 1997; Weckbach et al., 2008). We can regard these different activities of MK mentioned in this section are all aimed at promoting the repair of injured tissue, while excessive action of some activities leads to tissue damage.

MK in diseases

The diverse activities of MK described in the previous sections form the basis of its involvement in the pathogenesis of various diseases. As this subject will be fully explained in subsequent articles, only a brief summary is described here.

Consistent with the important role of MK in inflammation, MK deficiency attenuates various inflammation-related diseases, namely neointima formation upon ischaemia (a model of restenosis) (Horiba et al., 2000), ischaemic renal injury (Sato et al., 2001), drug-induced renal injury (Muramatsu, 2010; Kadomatsu et al., 2013), antibody-induced arthritis (a model of rheumatoid arthritis) (Maruyama et al., 2004), adhesion after surgery (Inoh et al., 2004) and experimental autoimmune encephalitis (a model of multiple sclerosis) (Wang et al., 2008), raising the possibility of drug development targeting MK for treatment of the above-mentioned diseases. Drugs targeting MK include antibodies, aptamers, low molecular weight compounds and nucleic acid reagents suppressing the formation and/or action of MK mRNA (Muramatsu, 2011; Kadomatsu et al., 2013).

MK is also up-regulated in the majority of human malignant tumours and contributes to tumour development and progression by enhancing the growth, survival, migration, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and angiogenic activity of these cells (Tsutsui et al., 1993; Aridome et al., 1995; Kadomatsu and Muramatsu, 2004; Muramatsu, 2010, 2011; Erguven et al., 2012). Strong MK expression in the tumour is correlated with the poor prognosis of patients and resistance to chemotherapy (Muramatsu, 2010; 2011,; Kadomatsu et al., 2013). Thus, anti-MK reagents are expected to be effective in the treatment of malignant diseases (Takei et al., 2001; Muramatsu, 2010; 2011,; Erguven et al., 2012; Kadomatsu et al., 2013). In addition, the promoter region of MK can be used to express toxic genes in tumour cells (Tagawa et al., 2012). Furthermore, circulating MK is a promising tumour marker (Krzystek-Korpacka and Matusiewicz, 2012).

MK also plays important roles in the regulation of blood pressure via the renin-angiotensin system (Ezquerra et al., 2005; Hobo et al., 2009). Partial nephrectomy induces MK expression in the lung, and the induced MK acts on endothelial cells to promote the expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme, leading to hypertension (Hobo et al., 2009). Therefore, MK appears to be a key molecule in the aetiology of hypertension upon chronic nephritis.

MK signalling

Consistent with the various in vivo activities of MK mentioned above, MK exerts many in vitro activities. Prominent activities fall into the following three categories: (i) enhancement of the survival of target cells such as embryonic neurons (Michikawa et al., 1993; Owada et al., 1999), neural precursor cells (Zou et al., 2006a) and B cells (Cohen et al., 2012); (ii) promotion of the expression of other cytokines by MK in renal epithelial cells (Sato et al., 2001), endothelial cells (Sumi et al., 2012) and bone marrow cells (Sonobe et al., 2012); and (iii) promotion of the migration of embryonic neurons (Maeda et al., 1999), macrophages (Horiba et al., 2000), neutrophils (Takada et al., 1997; Horiba et al., 2000) and osteoblast-like cells (Qi et al., 2001). Promotion of migration is mainly performed by substratum-bound MK, while other activities are mainly performed by soluble MK. In addition to the promotion of migration, MK has the following activities with potential involvement of the cytoskeleton, namely promotion of neurite outgrowth, clustering of ACh receptor in the neuromuscular junction and induction of collagen gel contraction by fibroblasts (Muramatsu et al., 1993; Kaneda et al., b1996; Muramatsu, 2010; 2011,). Besides cytokines, MK induces the expression of molecules in extracellular matrices (Muramatsu, 2010) and angiotensin-converting enzyme (Hobo et al., 2009). MK activities related to cell differentiation include enhanced differentiation of regulatory T-cells via tolerogenic dendritic cells (Wang et al., 2008; Sonobe et al., 2012), induction of adipocyte differentiation (Cernkovich et al., 2007) and induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Huang et al., 2008a).

Other activities are enhancement of growth (Muramatsu et al., 1993; Zou et al., 2006a; Muramatsu, 2010; Reiff et al., 2011; Shen et al., 2012), fibrinolytic activity (Kojima et al., 1997), angiogenic activity Weckbach et al. (2012) and anti-microbial activity (Svensson et al., 2010). Some of these activities have been used to analyse the signalling system of MK.

MK signalling is largely mediated by cell surface receptors, and several membrane proteins have been identified as MK receptors. Among them, the most established is PTPζ.

PTPζ is a transmembrane protein with intracellular tyrosine phosphatase domain and extracellular chondroitin sulfate chain and also serves as a PTN receptor (Maeda et al., 1999). Chondroitin sulfate portion of PTPζ is important for binding to MK as after enzymatic removal of chondroitin sulfate, the high-affinity binding site to MK (Kd, 0.58 nM) disappears, and only the low-affinity binding site (Kd, 8.8 nM) remains (Maeda et al., 1999).

As an MK receptor, PTPζ has been shown to be involved in migration of embryonic neurons (Maeda et al., 1999) and UMR106 osteoblast-like cells (Qi et al., 2001), survival of embryonic neurons (Sakaguchi et al., 2003) and B cells (Cohen et al., 2012), and suppression of the proliferation of osteoblasts (Liedert et al., 2011). Consistent with the important role of PTPζ in MK signalling, genetic analysis suggests that Drosophila miple functions also through PTPζ (Munoz-Soriano et al., 2013).

After ligand receptor interactions of PTPζ with MK or PTN, tyrosine phosphorylation is increased in cytoplasmic signalling molecules such as β-catenin, (Meng et al., 2000; Liedert et al., 2011), β-adducin (Pariser et al., 2005a), Fyn (Pariser et al., 2005b), Syk (Cohen et al., 2012) and Akt (Qi et al., 2001; Cohen et al., 2012). It is likely that after ligand stimulation, PTPζ is dimerized, leading to inactivation of the intracellular phosphatase domain, and results in increased tyrosine phosphorylation. The finding that oligomerization of PTPζ by antibodies or an artificial dimerizer leads to its inactivation (Fukada et al., 2006) is consistent with this view.

There are two isoforms of PTPζ, the full-length form and the short form. They are functionally different, and the full-length form appears to mediate the action of PTN in hippocampal neurons. PTN increases the density of hippocampal dendritic synapses, and overexpression of the full-length form decreases the density (Asai et al., 2009). This observation is consistent with the action mechanism of PTPζ described above. Finally, it is proper to mention that another mechanism has been proposed for the action of PTPζ, namely PTPζ dephosphorylates Src, leading to its activation (Polykratis et al., 2005).

Multiple kinases, that is, PI3K, MAPK, a Src family kinase and PKC, appear to be involved in signalling downstream from PTPζ, as revealed by their inhibitors (Qi et al., 2001). MK-induced phosphorylation of Akt in these cells has verified the role of PI3K in the signalling system (Qi et al., 2001). In the promotion of survival of B lymphocytes by MK, increased phosphorylation of Syk and Akt via PTPζ leads to increased Bcl-2 expression (Cohen et al., 2012).

Dephosphorylation of β-catenin is a critical step in canonical Wnt signalling. In osteoblasts, MK has been shown to inhibit osteoblast proliferation by interfering in Wnt signalling by inhibiting PTPζ-mediated dephosphorylation of β-catenin (Liedert et al., 2011).

DNER, a Notch-related receptor, forms a complex with PTPζ (Fukazawa et al., 2008). After PTN stimulation, tyrosine phosphorylation of DNER is increased, probably by the inhibition of PTPζ activity, leading to the inhibition of DNER endocytosis, and results in the promotion of neurite outgrowth in neuroblastoma cells. A similar mechanism can be considered upon MK-induced neurite outgrowth in embryonic neurons.

New classes of MK receptors, namely low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1 (LRP-1) (Muramatsu et al., 2000), α4β1-integrin and α6β1-integrin (Muramatsu et al., 2004) have been identified by analysing MK-binding proteins from day 13 mouse embryos. LRP-1 is a member of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family and binds to MK with a Kd of 3.5 nM (Muramatsu et al., 2000). Among the family members, megalin (Muramatsu et al., 2000) and ectodomains of LRP-6 and apo-E receptor-2 (Sakaguchi et al., 2003) also bind to MK, but with less affinity than that of LRP-1. LRP-1 serves as an MK receptor upon survival of embryonic neurons (Muramatsu et al., 2000) and prevention of hypoxic injury in mouse embryonic stem cells (Lee et al., 2012). In the latter system, MK signal is transmitted through Akt and hypoxia-induced factor (HIF)1α.

α4β1-integrin serves as an MK receptor upon migration of UMR-106 osteoblastic cells, and α6β1-integrin for neurite outgrowth of embryonic neurons (Muramatsu et al., 2004). Furthermore, these integrins, LRP-6 ectodomain and PTPζ form a molecular complex, and MK promotes complex formation (Muramatsu et al., 2004). As the result of MK action, tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin, which is downstream in the integrin signalling system, is increased in UMR-106 cells (Muramatsu et al., 2004). In human head and neck carcinoma cells, MK binds to tetraspanin and α6β1-integrin and enhances their association, leading to activation of focal adhesion kinase, paxillin and STAT1α pathway, resulting in enhanced migration and invasiveness of these cells (Huang et al., 2008b). αVβ3-integrin and PTPζ are receptors for PTN upon migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (Mikelis et al., 2009). PTN binds directly to both receptors, which interact mutually. Interestingly, MK does not bind to αVβ3-integrin and does not enhance the migration of these cells (Mikelis et al., 2009). All these results indicate that integrins are components of MK and PTN receptors to enhance cell migration and function in a molecular complex.

Neuroglycan C is a brain-specific chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan and serves as an MK receptor upon process elongation of CG-4 oligodendroglial precursor-like cells (Ichihara-Tanaka et al., 2006). MK can bind to neuroglycan C devoid of chondroitin sulfate, but the presence of chondroitin sulfate increases binding affinity (Ichihara-Tanaka et al., 2006). The Kd value of MK to recombinant neuroglycan C fusion protein without chondroitin sulfate is 51.8 nM (Ichihara-Tanaka et al., 2006). Further studies revealed that neuroglycan C also functions in a molecular complex (K. Ichihara-Tanaka et al., unpublished results).

Anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase involved in the tumourigenesis of at least several malignant tumours, such as anaplastic large cell lymphoma (Kadomatsu et al., 2013). ALK has been shown to be a receptor of MK (Stoica et al., 2002) and PTN. MK-dependent growth of SW-13 cells in soft agar requires ALK (Stoica et al., 2002). Furthermore, ALK plays the central role in MK-dependent proliferation of immature sympathetic neurons (Reiff et al., 2011) and MK-dependent resistance to cannabinoid of glioblastoma cells (Lorente et al., 2013).

After stimulation by MK, ALK phosphorylates insulin receptor substrate-1, leading to activation of MAPK, PI3K and NF-κB (Kuo et al., 2007). The apparent Kd value between MK and ALK was estimated to be 170 pM, based on the binding to ALK-expressing cells (Stoica et al., 2002). However, it is not established whether ALK directly binds to MK with high affinity. Furthermore, ALK formed a complex with LRP-6 ectodomain and integrins (H. Muramatsu et al. unpublished results). Therefore, ALK may work in the receptor complex for MK. Indeed, PTN-induced activation of ALK is mediated by PTPζ in MCF-7 cells (Perez-Pinera et al., 2007).

Notch-2, a transmembrane protein belonging to the Notch family, is an MK receptor inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition of immortalized HaCaT keratinocytes (Huang et al., 2008a). Direct binding of MK and Notch-2 has been shown by yeast 2-hybrid analysis and co-immunoprecipitation. After MK stimulation, JAK2 and STAT3 are recruited to hairy and enhancer of split-1 (Hes1), a transcription factor of the Notch signalling system, resulting in increased phosphorylation and activation of STAT3 (Huang et al., 2008a). Notch-2 also serves as an MK receptor in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cells to drive epithelial-mesenchymal transition and chemoresistance (Gungor et al., 2011). In these cells, MK induces cleavage of the Notch-2 cytoplasmic domain and stimulates the expression of Hes1 and NF-κB. Furthermore, Notch-2 participates in MK signalling upon development of neuroblastoma (Kishida et al., 2012). The Notch signalling system might also be involved in MK-induced production of chemokines because IL8 gene is activated after MK stimulation in keratinocytes (Huang et al., 2008a). The possibility that Notch-2 acts in the receptor complex is not excluded because DNER, a Notch-related transmembrane protein, forms a complex with PTPζ (Fukazawa et al., 2008).

Most MK activities are inhibited by heparin or digestion with heparitinase or chondroitinase, indicating the importance of carbohydrate recognition in MK signalling (Muramatsu, 2010). Two oligomeric carbohydrate structures, namely heparan sulfate trisulfated units and chondroitin sulfate E units, have been shown to bind to MK strongly (Kaneda et al., a1996; Ueoka et al., 2000; Muramatsu et al., 2003; Zou et al., 2003; Muramatsu, 2010). Chondroitin sulfate chains are present in PTPζ and neuroglycan C, as mentioned above. Furthermore, versican, another chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan, also binds to MK (Zou et al., 2000). Although versican is not a transmembrane protein, but a pericellular protein, it can function in the delivery of MK to the receptor.

Syndecans and glypican-2 are heparan sulfate proteoglycans with MK binding activity (Muramatsu, 2010). Kd of syndecan-4 to MK is 0.30 nM (Kojima et al., 1996). Transfection of syndecan-3 or glypican-2 cDNA to neurobalstoma cells results in extension of neurites on the MK-coated substratum (Kurosawa et al., 2001).

Although several transmembrane proteins have been identified as MK receptors, as mentioned above, none has very high affinity to MK or is specific only to the MK/PTN family. Therefore, it might be reasonable to assume that MK frequently binds to more than one component in the receptor complex to exert its function. That MK can form a dimer (Kojima et al., 1997) is important as dimeric MK is suitable for enhancing the association of different components in the receptor complex.

The signalling systems downstream from the MK receptors are diverse, as mentioned above, while the PI3K/Akt system and MAPK appear to play central roles in many cases. Notably, the PI3K /Akt system is involved in the survival of embryonic neurons (Owada et al., 1999) and B cells (Cohen et al., 2012), prevention of hypoxic injury in embryonic stem cells (Lee et al., 2012), and migration of osteoblast-like cells (Qi et al., 2001). Upon promotion of survival by MK, suppression of caspase and activation of Bcl-2 are observed after signalling (Owada et al., 1999; Qi et al., 2000; Muramatsu, 2010; Cohen et al., 2012).

Transcriptional factors, whose activities are regulated by signalling cascades triggered by MK, include NF-κB (Kuo et al., 2007; Gungor et al., 2011), Hes-1 (Gungor et al., 2011), HIF-1α (Lee et al., 2012) and STATs (Cernkovich et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2008a; b2008b; Sonobe et al., 2012).

Among them, STATs require further description. Activation of STAT1α is involved in the migration of head and neck carcinoma cells (Huang et al., 2008b), while activation of STAT3 is important in epithelial-mesenchymal transition of keratinocytes (Huang et al., 2008a) and the proliferation and adipogenesis of 3T3-L1 cells (Cernkovich et al., 2007). However, in bone marrow cells containing tolerogenic dendritic cells, MK activates SHP-2 (src homology region 2 domain-containing phosphatase-2) (Sonobe et al., 2012). This effect leads to decreased phosphorylation of STAT3α upon IL-10 stimulation and to increased production of IL-12.

In addition to receptor-mediated signalling, a portion of MK has been shown to exert its effect directly in the nucleus. MK is internalized after binding to LRP-1 and is then transported to the nucleus by binding to nucleolin (Shibata et al., 2002) or to laminin-binding protein precursor (Salama et al., 2001), and is involved in the promotion of cell survival (Shibata et al., 2002). Furthermore, MK transferred to the nucleolus enhances the synthesis of ribosomal RNA (Dai et al., 2008).

In conclusion, various aspects of MK signalling have been clarified in detail, while further efforts are required to reveal the complete image of MK signalling. Thus, there remain possibilities that new targets will emerge for suppression of the MK signalling system.

Glossary

- ALK

anaplastic lymphoma kinase

- Hes-1

hairy and enhancer of split-1

- HIF

hypoxia-induced factor

- LRP

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein

- Mdka

Midkine-a

- Mdkb

Midkine-b

- MK

midkine

- PTN

pleiotrophin

- PTPζ

receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase Z1

Conflict of interest

None declared.

References

- Adachi Y, Matsubara S, Pedraza C, Ozawa M, Tsutsui J, Takamatsu H, et al. Midkine as a novel target gene for the Wilms' tumor suppressor gene (WT1) Oncogene. 1996;13:2197–2203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed KM, Shitara Y, Takenoshita S, Kuwano H, Saruhashi S, Shinozawa T. Association of an intronic polymorphism in the midkine gene with human sporadic colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2002;180:159–163. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(02)00040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter S, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Kojima S, Muramatsu H, Inui T, Kimura T, et al. Clusters of basic amino acids in midkine: roles in neurite-promoting activity and plasminogen activator-enhancing activity. J Biochem. 1998;123:1127–1136. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aridome K, Tsutsui J, Takao S, Kadomatsu K, Ozawa M, Aikou T, et al. Increased midkine gene expression in human gastrointestinal cancers. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995;86:655–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb02449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai H, Yokoyama S, Morita S, Maeda N, Miyata S. Functional difference of receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase ζ/β isoforms in neurogenesis of hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2009;164:1020–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai T, Watanabe K, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Kaneda N, Kojima S, Iguchi A, et al. Identification of heparin-binding sites in midkine and their role in neurite-promotion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;236:66–70. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernkovich ER, Deng J, Hua K, Harp JB. Midkine is an autocrine activator of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 in 3T3-L1 cells. Endocrinology. 2007;148:1598–1604. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhuri R, Zhang HT, Donnini S, Ziche M, Bicknell R. An angiogenic role for the neurokines midkine and pleiotrophin in tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1814–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Shoshana OY, Zelman-Toister E, Maharshak N, Binsky-Ehrenreich I, Gordin M, et al. The cytokine midkine and its receptor RPTPζ regulate B cell survival in a pathway induced by CD74. J Immunol. 2012;188:259–269. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai LC, Shao JZ, Min LS, Xiao YT, Xiang LX, Ma ZH. Midkine accumulated in nucleolus of HepG2 cells involved in rRNA transcription. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6249–6253. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englund C, Birve A, Falileeva L, Grabbe C, Palmer RH. Miple1 and miple2 encode a family of MK/PTN homologues in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Genes Evol. 2006;216:10–18. doi: 10.1007/s00427-005-0025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erguven M, Muramatsu T, Bilir A, editors. Midkine: From Embryogenesis to Pathogenesis and Therapy. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ezquerra L, Herradon G, Nguyen T, Silos-Santiago I, Deuel TF. Midkine, a newly discovered regulator of the renin-angiotensin pathway in mouse aorta: significance of the pleiotrophin/midkine developmental gene family in angiotensin II signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:636–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabri L, Maruta H, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T, Simpson RT, Burges AW, et al. Structural characterisation of native and recombinant forms of the neurotrophic cytokine MK. J Chromatogr. 1993;646:213–225. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(99)87023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan QW, Muramatsu T, Kadomatsu K. Distinct expression of midkine and pleiotrophin in the spinal cord and placental tissues during early mouse development. Dev Growth Differ. 2000;42:113–119. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2000.00497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukada M, Fujikawa A, Chow JP, Ikematsu S, Sakuma S, Noda M. Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type ζ is inactivated by ligand-induced oligomerization. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4051–4056. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukazawa N, Yokoyama S, Eiraku M, Kengaku M, Maeda N. Receptor type protein tyrosine phosphatase ζ-pleiotrophin signaling controls endocytic trafficking of DNER that regulates neuritogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4494–4506. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00074-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gramage E, Martin YB, Ramanah P, Perez-Garcia C, Herradon G. Midkine regulates amphetamine-induced astrocytosis in striatum but has no effects on amphetamine-induced striatal dopaminergic denervation and addictive effects: functional differences between pleiotrophin and midkine. Neuroscience. 2011;190:307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gungor C, Zander H, Effenberger KE, Vashist YK, Kalinina T, Izbicki JR, et al. Notch signaling activated by replication stress-induced expression of midkine drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition and chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5009–5019. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herradon G, Ezquerra L, Nguyen T, Silos-Santiago I, Deuel TF. Midkine regulates pleiotrophin organ-specific gene expression: evidence for transcriptional regulation and functional redundancy within the pleiotrophin/midkine developmental gene family. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:714–721. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobo A, Yuzawa Y, Kosugi T, Kato N, Asai N, Sato W, et al. The growth factor midkine regulates the renin-angiotensin system in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1616–1625. doi: 10.1172/JCI37249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiba M, Kadomatsu K, Nakamura E, Muramatsu H, Ikematsu S, Sakuma S, et al. Neointima formation in a restenosis model is suppressed in midkine-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:489–495. doi: 10.1172/JCI7208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiba M, Kadomatsu K, Yasui K, Lee JK, Takenaka H, Sumida A, et al. Midkine plays a protective role against cardiac ischemia/reperfusion injury through a reduction of apoptotic reaction. Circulation. 2006;114:1713–1720. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.632273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Hoque MO, Wu F, Trink B, Sidransky D, Ratovitski EA. Midkine induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition through Notch2/Jak2-Stat3 signaling in human keratinocytes. Cell Cycle. 2008a;7:1613–1622. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.11.5952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Sook-Kim M, Ratovitski E. Midkine promotes tetraspanin-integrin interaction and induces FAK-Stat1α pathway contributing to migration/invasiveness of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008b;377:474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara-Tanaka K, Oohira A, Rumsby M, Muramatsu T. Neuroglycan C is a novel midkine receptor involved in process elongation of oligodendroglial precursor-like cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30857–30864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda S, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Azuma T, Muramatsu T, Yamada M. Effects of midkine during in vitro maturation of bovine oocytes on subsequent developmental competence. Biol Reprod. 2000;63:1067–1074. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.4.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inazumi T, Tajima S, Nishikawa T, Kadomatsu K, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T. Expression of the retinoid-inducible polypeptide, midkine, in human epidermal keratinocytes. Arch Dermatol Res. 1997;289:471–475. doi: 10.1007/s004030050223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoh K, Muramatsu H, Ochiai K, Torii S, Muramatsu T. Midkine, a heparin-binding cytokine, plays key roles in intraperitoneal adhesions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;317:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki W, Nagata K, Hatanaka H, Inui T, Kimura T, Muramatsu T, et al. Solution structure of midkine, a new heparin-binding growth factor. EMBO J. 1997;16:6936–6946. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.6936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadomatsu K, Muramatsu T. Midkine and pleiotrophin in neural development and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2004;204:127–143. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(03)00450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadomatsu K, Tomomura M, Muramatsu T. cDNA cloning and sequencing of a new gene intensely expressed in early differentiation stages of embryonal carcinoma cells and in mid-gestation period of mouse embryogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;151:1312–1318. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)80505-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadomatsu K, Huang RP, Suganuma T, Murata F, Muramatsu T. A retinoic acid responsive gene MK found in the teratocarcinoma system is expressed in spatially and temporally controlled manner during mouse embryogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:607–616. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.3.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadomatsu K, Kishida S, Tsubota S. The heparin-binding growth factor midkine: the biological activities and candidate receptors. J Biochem. 2013;153:511–521. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvt035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaname T, Kuwano A, Murano I, Uehara K, Muramatsu T, Kajii T. Midkine gene (MDK), a gene for prenatal differentiation and neuroregulation, maps to band 11p11.2 by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Genomics. 1993;17:514–515. doi: 10.1006/geno.1993.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaname T, Kadomatsu K, Aridome K, Yamashita S, Sakamoto K, Ogawa M, et al. The expression of truncated MK in human tumors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;219:256–260. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda N, Talukder AH, Ishihara M, Hara S, Yoshida K, Muramatsu T. Structural characteristics of heparin-like domain required for interaction of midkine with embryonic neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:108–112. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda N, Talukder AH, Nishiyama H, Koizumi S, Muramatsu T. Midkine, a heparin-binding growth/differentiation factor, exhibits nerve cell adhesion and guidance activity for neurite outgrowth in vitro. J Biochem. 1996;119:1150–1156. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan F, Comber J, Sladek R, Hudson TJ, Muglia LJ, Macrae T, et al. The growth factor midkine is modulated by both glucocorticoid and retinoid in fetal lung development. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:33–41. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0047oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpelainen I, Kaksonen M, Kinnunen T, Avikainen H, Fath M, Linhardt RJ, et al. Heparin-binding growth-associated molecule contains two heparin-binding β-sheet domains that are homologous to the thrombospondin type I repeat. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:13564–13570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.18.13564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida S, Mu P, Miyakawa S, Fujiwara M, Abe T, Sakamoto K, et al. Midkine promotes neuroblastoma through Notch2 signaling. Cancer Res. 2012;73:1318–1327. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima S, Inui T, Muramatsu H, Suzuki Y, Kadomatsu K, Yoshizawa M, et al. Dimerization of midkine by tissue transglutaminase and its functional implication. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9410–9416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima T, Katsumi A, Yamazaki T, Muramatsu T, Nagasaka T, Ohsumi K, et al. Human ryudocan from endothelium-like cells binds basic fibroblast growth factor, midkine, and tissue factor pathway inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5914–5920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzystek-Korpacka M, Matusiewicz M. Circulating midkine in malignant, inflammatory and infectious diseases: a systematic review. In: Erguven M, Muramatsu T, Bilir A, editors. Midkine: From Embryogenesis to Pathogenesis and Therapy. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer; 2012. pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kuo AH, Stoica GE, Riegel AT, Wellstein A. Recruitment of insulin receptor substrate-1 and activation of NF-κB essential for midkine growth signaling through anaplastic lymphoma kinase. Oncogene. 2007;26:859–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosawa N, Chen GY, Kadomatsu K, Ikematsu S, Sakuma S, Muramatsu T. Glypican-2 binds to midkine: the role of glypican-2 in neuronal cell adhesion and neurite outgrowth. Glycoconj J. 2001;18:499–507. doi: 10.1023/a:1016042303253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Suh HN, Lee YJ, Seo BN, Ha JW, Han HJ. Midkine prevented hypoxic injury of mouse embryonic stem cells through activation of Akt and HIF-1α via low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein-1. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:1731–1739. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedert A, Mattausch L, Rontgen V, Blakytny R, Vogele D, Pahl M, et al. Midkine-deficiency increases the anabolic response of cortical bone to mechanical loading. Bone. 2011;48:945–951. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke D, Winkler C. Midkine-b regulates cell specification at the neural plate border in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:62–74. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Yao S, Graf M, Winkler C, Yang D. Structure-function analysis of full-length midkine reveals novel residues important for heparin-binding and zebrafish embryogenesis. Biochem J. 451:407–415. doi: 10.1042/BJ20121622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorente M, Torres S, Salazar M, Carracedo A, Hernández-Tiedra S, Rodríguez-Fornés F, et al. Stimulation of the midkine/ALK axis renders glioblastoma cells resistant to cannabinoid antitumoral action. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18:959–973. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda N, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Kimura T, Kadomatsu K, Muramatsu T, Noda M. A receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase PTPζ/RPTPβ binds a heparin-binding growth factor midkine. Involvement of arginine 78 of midkine in the high affinity binding to PTPζ. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12474–12479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama K, Muramatsu H, Ishiguro N, Muramatsu T. Midkine, a heparin-binding growth factor, is fundamentally involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1420–1429. doi: 10.1002/art.20175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda Y, Talukder AH, Ishihara M, Hara S, Yoshida K, Muramatsu T, et al. Limited proteolysis by chymotrypsin of midkine and inhibition by heparin binding. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;228:176–181. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Wanaka A, Takatsuji K, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T, Tohyama M. A novel family of heparin-binding growth factors, pleiotrophin and midkine, is expressed in the developing rat cerebral cortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1994;79:229–241. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90127-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng K, Rodriguez-Pena A, Dimitrov T, Chen W, Yamin M, Noda M, et al. Pleiotrophin signals increased tyrosine phosphorylation of β-catenin through inactivation of the intrinsic catalytic activity of the receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase β/ζ. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2603–2608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.020487997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michikawa M, Kikuchi S, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T, Kim SU. Retinoic acid responsive gene product, midkine, has neurotrophic functions for mice spinal cord and dorsal root ganglion neurons in culture. J Neurosci Res. 1993;35:530–539. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikelis C, Sfaelou E, Koutsioumpa M, Kieffer N, Papadimitriou E. Integrin αvβ3 is a pleiotrophin receptor required for pleiotrophin-induced endothelial cell migration through receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase β/ζ. FASEB J. 2009;23:1459–1469. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-117564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner PG, Li YS, Hoffman RM, Kodner CM, Siegel NR, Deuel TF. A novel 17 kD heparin-binding growth factor (HBGF-8) in bovine uterus: purification and N-terminal amino acid sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;165:1096–1103. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsiadis TA, Muramatsu T, Muramatsu H, Thesleff I. Midkine (MK), a heparin-binding growth/differentiation factor, is regulated by retinoic acid and epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the developing mouse tooth, and affects cell proliferation and morphogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1995a;129:267–281. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsiadis TA, Salmivirta M, Muramatsu T, Muramatsu H, Rauvala H, Lehtonen E, et al. Expression of the heparin-binding cytokines, midkine (MK) and HB-GAM (pleiotrophin) is associated with epithelial-mesenchymal interactions during fetal development and organogenesis. Development. 1995b;121:37–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Soriano V, Ruiz C, Perez-Alonso M, Mlodzik M, Paricio N. Nemo regulates cell dynamics and represses the expression of miple, a midkine/pleiotrophin cytokine, during ommatidial rotation. Dev Biol. 2013;377:113–125. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H, Shirahama H, Yonezawa S, Maruta H, Muramatsu T. Midkine, a retinoic acid-inducible growth/differentiation factor: immunochemical evidence for the function and distribution. Dev Biol. 1993;159:392–402. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H, Inui T, Kimura T, Sakakibara S, Song XJ, Maruta H, et al. Localization of heparin-binding, neurite outgrowth and antigenic regions in midkine molecule. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;203:1131–1139. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H, Zou K, Sakaguchi N, Ikematsu S, Sakuma S, Muramatsu T. LDL receptor-related protein as a component of the midkine receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:936–941. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H, Zou P, Suzuki H, Oda Y, Chen GY, Sakaguchi N, et al. 4β1-and α6β1-integrins are functional receptors for midkine, a heparin-binding growth factor. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:5405–5415. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu H, Zou P, Kurosawa N, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Maruyama K, Inoh K, et al. Female infertility in mice deficient in midkine and pleiotrophin, which form a distinct family of growth factors. Genes Cells. 2006;11:1405–1417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu T. Midkine and pleiotrophin: two related proteins involved in development, survival, inflammation and tumorigenesis. J Biochem. 2002;132:359–371. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu T. Midkine, a heparin-binding cytokine with multiple roles in development, repair and diseases. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2010;86:410–425. doi: 10.2183/pjab.86.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu T. Midkine: a promising molecule for drug development to treat diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17:410–423. doi: 10.2174/138161211795164167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu T, Muramatsu H, Kaneda N, Sugahara K. Recognition of glycosaminoglycans by midkine. Methods Enzymol. 2003;363:365–376. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)01065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto A, Imagama S, Natori T, Wakao N, Ando K, Tauchi R, et al. Midkine overcomes neurite outgrowth inhibition of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan without glial activation and promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Neurosci Lett. 550:150–155. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordin SL, Andersson C, Bjermer L, Bjartell A, Morgelin M, Egesten A. Midkine is part of the antibacterial activity released at the surface of differentiated bronchial epithelial cells. J Innate Immun. 5:519–530. doi: 10.1159/000346709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novotny WF, Maffi T, Mehta RL, Milner PG. Identification of novel heparin-releasable proteins, as well as the cytokine midkine and pleiotrophin, in human postheparin plasma. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1798–1805. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.12.1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obama H, Biro S, Tashiro T, Tsutsui J, Ozawa M, Yoshida H, et al. Myocardial infarction induces expression of midkine, a heparin-binding growth factor with reparative activity. Anticancer Res. 1998;18:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochiai K, Muramatsu H, Yamamoto S, Ando H, Muramatsu T. The role of midkine and pleiotrophin in liver regeneration. Liver Int. 2004;24:484–491. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgake S, Shimizu E, Hashimoto K, Okamura N, Koike K, Koizumi H, et al. Dopaminergic hypofunctions and prepulse inhibition deficits in mice lacking midkine. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:541–546. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta S, Muramatsu H, Senda T, Zou K, Iwata H, Muramatsu T. Midkine is expressed during repair of bone fracture and promotes chondrogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1132–1144. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.7.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohyama Y, Miyamoto K, Minamino N, Matsuo H. Isolation and identification of midkine and pleiotrophin in bovine follicular fluid. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1994;105:203–208. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owada K, Sanjo N, Kobayashi T, Mizusawa H, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T, et al. Midkine inhibits caspase-dependent apoptosis via the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in cultured neurons. J Neurochem. 1999;73:2084–2092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariser H, Herradon G, Ezquerra L, Perez-Pinera P, Deuel TF. Pleiotrophin regulates serine phosphorylation and the cellular distribution of β-adducin through activation of protein kinase C. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005a;102:12407–12412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505901102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pariser H, Ezquerra L, Herradon G, Perez-Pinera P, Deuel TF. Fyn is a downstream target of the pleiotrophin/receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase β/ζ signaling pathway: regulation of tyrosine phosphorylation of Fyn by pleiotrophin. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005b;332:664–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Mitsumoto T, Asano Y, Kato S, Kato M, Shinozawa T. Detection of truncated midkine in Wilms' tumor by a monoclonal antibody against human recombinant truncated midkine. Cancer Lett. 2001;163:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(00)00696-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedraza C, Matsubara S, Muramatsu T. A retinoic acid-responsive element in human midkine gene. J Biochem. 1995;117:845–849. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pinera P, Zhang W, Chang Y, Vega JA, Deuel TF. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase is activated through the pleiotrophin/receptor protein-tyrosine phosphatase β/ζ signaling pathway: an alternative mechanism of receptor tyrosine kinase activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28683–28690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704505200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polykratis A, Katsoris P, Courty J, Papadimitriou E. Characterization of heparin affin regulatory peptide signaling in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22454–22461. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prediger RD, Rojas-Mayorquin AE, Aguiar AS, Jr, Chevarin C, Mongeau R, Hamon M, et al. Mice with genetic deletion of the heparin-binding growth factor midkine exhibit early preclinical features of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:1215–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Ikematsu S, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Sakuma S, Muramatsu T, Kadomatsu K. Midkine rescues Wilms' tumor cells from cisplatin-induced apoptosis: regulation of Bcl-2 expression by midkine. J Biochem. 2000;127:269–277. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi M, Ikematsu S, Maeda N, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Sakuma S, Noda M, et al. Haptotactic migration induced by midkine. Involvement of protein-tyrosine phosphatase ζ. Mitogen-activated protein kinase, and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15868–15875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m005911200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raulais D, Lagente-Chevallier O, Guettet C, Duprez D, Courtois Y, Vigny M. A new heparin binding protein regulated by retinoic acid from chick embryo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;174:708–715. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91475-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauvala H. An 18-kd heparin-binding protein of developing brain that is distinct from fibroblast growth factors. EMBO J. 1989;8:2933–2941. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiff T, Huber L, Kramer M, Delattre O, Janoueix-Lerosey I, Rohrer H. Midkine and Alk signaling in sympathetic neuron proliferation and neuroblastoma predisposition. Development. 2011;138:4699–4708. doi: 10.1242/dev.072157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds PR, Mucenski ML, Le Cras TD, Nichols WC, Whitsett JA. Midkine is regulated by hypoxia and causes pulmonary vascular remodeling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37124–37132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405254200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakaguchi N, Muramatsu H, Ichihara-Tanaka K, Maeda N, Noda M, Yamamoto T, et al. Receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase ζ as a component of the signaling receptor complex for midkine-dependent survival of embryonic neurons. Neurosci Res. 2003;45:219–224. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(02)00226-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salama RH, Muramatsu H, Zou K, Inui T, Kimura T, Muramatsu T. Midkine binds to 37-kDa laminin binding protein precursor, leading to nuclear transport of the complex. Exp Cell Res. 2001;270:13–20. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato W, Kadomatsu K, Yuzawa Y, Muramatsu H, Hotta N, Matsuo S, et al. Midkine is involved in neutrophil infiltration into the tubulointerstitium in ischemic renal injury. J Immunol. 2001;167:3463–3469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer M, Rembold M, Wittbrodt J, Schartl M, Winkler C. Medial floor plate formation in zebrafish consists of two phases and requires trunk-derived Midkine-a. Genes Dev. 2005;19:897–902. doi: 10.1101/gad.336305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen W, Park BW, Toms D, Li J. Midkine promotes proliferation of primordial germ cells by inhibiting the expression of the deleted in azoospermia-like gene. Endocrinology. 2012;153:3482–3492. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata Y, Muramatsu T, Hirai M, Inui T, Kimura T, Saito H, et al. Nuclear targeting by the growth factor midkine. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6788–6796. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.19.6788-6796.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone M, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T, Nakashima T. Morphological observation of the stria vascularis in midkine and pleiotrophin knockout mice. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonobe Y, Li H, Jin S, Kishida S, Kadomatsu K, Takeuchi H, et al. Midkine inhibits inducible regulatory T cell differentiation by suppressing the development of tolerogenic dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2012;188:2602–2611. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoica GE, Kuo A, Powers C, Bowden ET, Sale EB, Riegel AT, et al. Midkine binds to anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) and acts as a growth factor for different cell types. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:35990–35998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumi Y, Muramatsu H, Takei Y, Hata K, Ueda M, Muramatsu T. Midkine, a heparin-binding growth factor, promotes growth and glycosaminoglycan synthesis of endothelial cells through its action on smooth muscle cells in an artificial blood vessel model. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:2659–2667. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.13.2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson SL, Pasupuleti M, Walse B, Malmsten M, Mörgelin M, Sjögren C, et al. Midkine and pleiotrophin have bactericidal properties: preserved antibacterial activity in a family of heparin-binding growth factors during evolution. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16105–16115. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.081232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagawa M, Kawamura K, Yu L, Tada Y, Hiroshima K, Shimada H. A gene medicine with the midkine-mediated transcriptional regulation as new cancer therapeutics. In: Erguven M, Muramatsu T, Bilir A, editors. Midkine: From Embryogenesis to Pathogenesis and Therapy. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer; 2012. pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Takada T, Toriyama K, Muramatsu H, Song XJ, Torii S, Muramatsu T. Midkine, a retinoic acid-inducible heparin-binding cytokine in inflammatory responses: chemotactic activity to neutrophils and association with inflammatory synovitis. J Biochem. 1997;122:453–458. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei Y, Kadomatsu K, Matsuo S, Itoh H, Nakazawa K, Kubota S, et al. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotide targeted to Midkine, a heparin-binding growth factor, suppresses tumorigenicity of mouse rectal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8486–8491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K, Duquette M, Liu JH, Dong Y, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, et al. Crystal structure of the TSP-1 type 1 repeats: a novel layered fold and its biological implication. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:373–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomomura M, Kadomatsu K, Matsubara S, Muramatsu T. A retinoic acid-responsive gene, MK, found in the teratocarcinoma system. Heterogeneity of the transcript and the nature of the translation product. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10765–10770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui J, Uehara K, Kadomatsu K, Matsubara S, Muramatsu T. A new family of heparin-binding factors: strong conservation of midkine (MK) sequences between the human and the mouse. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;176:792–797. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80255-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui J, Kadomatsu K, Matsubara S, Nakagawara A, Hamanoue M, Takao S, et al. A new family of heparin-binding growth/differentiation factors: increased midkine expression in Wilms' tumor and other human carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1281–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara K, Matsubara S, Kadomatsu K, Tsutsui J, Muramatsu T. Genomic structure of human midkine (MK), a retinoic acid-responsive growth/differentiation factor. J Biochem. 1992;111:563–567. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueoka C, Kaneda N, Okazaki I, Nadanaka S, Muramatsu T, Sugahara K. Neuronal cell adhesion, mediated by the heparin-binding neuroregulatory factor midkine, is specifically inhibited by chondroitin sulfate E. Structural and functional implications of the over-sulfated chondroitin sulfate. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:37407–37413. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002538200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unoki K, Ohba N, Arimura H, Muramatsu H, Muramatsu T. Rescue of photoreceptors from the damaging effects of constant light by midkine, a retinoic acid-responsive gene product. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:4063–4068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]