Abstract

We have developed an efficient transformation system for Tribulus terrestris L., an important medicinal plant, using Agrobacterium rhizogenes strains AR15834 and GMI9534 to generate hairy roots. Hairy roots were formed directly from the cut edges of leaf explants 10–14 days after inoculation with the Agrobacterium with highest frequency transformation being 49 %, which was achieved using Agrobacterium rhizogenes AR15834 on hormone-free MS medium after 28 days inoculation. PCR analysis showed that rolB genes of Ri plasmid of A. rhizogenes were integrated and expressed into the genome of transformed hairy roots. Isolated transgenic hairy roots grew rapidly on MS medium supplemented with indole-3-butyric acid. They showed characteristics of transformed roots such as fast growth and high lateral branching in comparison with untransformed roots. Isolated control and transgenic hairy roots grown in liquid medium containing IBA were analyzed to detect ß-carboline alkaloids by High Performance Thin Layer Chromatograghy (HPTLC). Harmine content was estimated to be 1.7 μg g−1 of the dried weight of transgenic hairy root cultures at the end of 50 days of culturing. The transformed roots induced by AR15834 strain, spontaneously, dedifferentiated as callus on MS medium without hormone. Optimum callus induction and shoot regeneration of transformed roots in vitro was achieved on MS medium containing 0.4 mg L−1 naphthaleneacetic acid and 2 mg L−1 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) after 50 days. The main objective of this investigation was to establish hairy roots in this plant by using A. rhizogenes to synthesize secondary products at levels comparable to the wild-type roots.

Keywords: Agrobacterium rhizogenes, Hairy roots, Harmine, Secondary metabolite, Transformation, Tribulus terrestris

Introduction

Tribulus terrestris L. is a well-known plant which grows in subtropical areas around the world and is widely used for isolation of pharmacologically active compounds such as saponins, flavonoids, β-carboline alkaloids, phytosteroids and other nutrients (Xu et al. 2001). The fruits have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of eye trouble, edema, abdominal distention, emission, morbid leucorrhea, sexual dysfunction, and veiling. Also, its roots and fruits are useful in rheumatism, piles, renal and vesical calculi, menorrhagia, impotency, premature ejaculation, general weakness etc. Its leaves purify blood and are used as aphrodisiac while its roots are used as stomachic and appetizer. Its components are also used as a tonic crude drug (Sarwat et al. 2008; Selvam 2008).

Generally, T. terrestris has a considerable seed dormancy lasting over fall and winter months (Washington State Noxious Weed Control Board 2001) with some seeds staying dormant for longer periods of time. Recently, a study has showed that germination of around 28 % the seeds of T. terrestris is normally delayed and takes upto 10 to 14 days to germinate (Sharifi et al. 2012). Also, the growth of this plant is very slow and it produces scanty biomass. Being a medicinal plant, T. terrestris is available only during a short period of growing season. Thus, the techniques of plant tissue culture and biotechnological intervention have augmented the production and availability of such plants throughout the year for meeting the growing industrial demand (Chaudhury and Pal 2010).

Hairy roots offer opportunities for stable (compared to undifferentiated cultures) and wide-range production of plant secondary metabolites (Giri and Narasu 2000; Hu and Du 2006; Georgiev et al. 2007). They also present a potential for the production of valuable secondary metabolites by obtaining high-yield lines developed via optimization of the inoculums conditions and nutrient medium compounds, elicitation, permeabilization and cultivation of hairy roots in two phase systems, large scale cultivation in bioreactor systems, and using genetic engineering technology (Georgiev et al. 2007). Many reviews have been published over the last decade on hairy root cultures which have provided with valuable knowledge to the scientific community working in the field (Toivonen 1993; Shanks et al. 1999; Giri and Narasu 2000; Kino-oka et al. 2001; Kim et al. 2002; Eibl and Eibl 2008; Mishra and Ranjan 2008). The phenotypic characteristics of transformed roots include: rapid growth, hormone autotrophy, reduced apical dominance, high branching and root plagiotropism (Tepfer and Tempe 1981) and one of the unique characteristics of hairy roots is their enhanced, stable production of secondary metabolites (Bourgaud et al. 2001). The sucrose level, exogenous growth hormone, the nature of the nitrogen source and their relative amounts, light, temperature and the presence of chemicals can all affect growth, total biomass yield, and secondary metabolite production (Rhodes et al. 1994; Nussbbaumer et al. 1998).

Despite the occurrence of medicinal and pharmaceutical importance of secondary metabolites, there are few reports of significant cultivation of this plant. There are few early reports of production of secondary metabolites from callus cultures of Tribulus (Jit and Nag 1985; Erhun and Sofowora 1986; Zafar and Hague 1990). The potential of callus culture of T. terrestris as a source of saponin and alkaloids was investigated by Nikam et al. (2009).

No investigation so far has been conducted on genetic transformation of T. terrestris with the soil-borne bacterium A. rhizogenes, which is responsible for the development of hairy root disease in a range of dicots (Tepfer 1984), and utilization of hairy roots or its regenerated plants to produce the secondary metabolites.

Transgenic hairy root culture has served as a useful model system to investigate the biosynthesis of a variety of secondary metabolites. This study is the first report of Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated genetic transformation of Tribulus terrestris L. using wild-type strain AR15834 while conditions have been optimized for induction of hairy root cultures as well as induction of harmine production.

Materials and methods

Growth of Agrobacterium rhizogenes

Two wild-type A. rhizogenes strains, AR15834 and GMI9534 were used in this study, both harboring Ri-plasmid (Root- inducing), namely. The Ri-plasmid contains genes like vir and rol which are essential for plant transformation. A. rhizogenes was cultured on liquid Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (Brown 1998) until mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.5–1) was achieved at 28 °C with shaking (180 rpm) in dark.

Young leaves and stem (0.5–1 cm) of in vivo grown 21 days and old plants of T. terrestris were surface sterilized for 3 min with 0.1 % (w/v) aqueous HgCl2, and then rinsed five times with sterile distilled water, then maintained on Murashige and Skoog medium (1962) and used as explants for A. rhizogenes transformation. Callus, epicotyls and leaves were used as explant for co-cultivation with A. rhizogenes strains AR15834 and GMI9534.

Leaves were wounded using a scalpel and were immersed in the A. rhizogenes suspensions and swirled in liquid inoculation medium for 3 to 5 min. The explants were blotted dry on sterile filter paper to remove excess of bacterial inoculum and incubated in the dark on cocultivation medium (MS medium). After 2 days of cocultivation, all the explants were washed thoroughly in 350 mg L−1 cefotaxime for 15 min. Then, they were transferred to hormone-free MS medium and MS supplemented with NAA, BAP, 3 % (w/v) sucrose, 7 g L−1 agar and 350 mg L−1 cefotaxime for 28 days, then sub-cultured on to fresh medium every two weeks. Numerous roots had emerged from the wound sites. Also, un-inoculated explants were used as a control. The rate of produced roots on selective medium to the number of cultured explants was determined. Roots formed at the wound sites of the infected explants were excised and cultured in the dark in Petridishes containing 25 ml MS supplemented with 350 mg L−1 cefotaxime to establish axenic transformed root cultures. The amount of cefotaxime in the culture medium was gradually reduced to 100 mg L−1. Each excised primary root was propagated as a separate clone and sub-cultured at 4-week intervals on cefotaxime-free MS medium supplemented with 1 mg L−1 and 2 mg L−1 IBA.

PCR analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from transgenic and non-transgenic (control) roots, by using the cetyl-trimethyl amonium bromide (CTAB) method (Murray and Thampson 1980). Integration of the rolB gene into the plant genome was confirmed by PCR analysis using gene-specific primers, 5′ –GCTCTTGCAGTGCTAGATTT-3′ and 5′ -GAA GGT GCA AGC TAC CTC TC-3′ for the forward and reverse, respectively. In order to amplify the rolB gene sequence, PCR was initiated by a hot start at 94 °C for 10 min and amplified during 30 cycles at 94 °C for 30s, 53 °C for 30s, 72 °C for 90s and followed by a final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min. The electrophoresis of the PCR products was performed on 1.2 % agarose gel under a constant voltage of 80 V. The gel was subsequently stained with ethidium bromide solution and examined under UV light.

Effect of growth regulators

Based on published literature and evalution of different external growth regulators on bacteria-free hairy roots, IBA was added at concentrations of 1 mg L−1 and 2 mg L−1 on MS medium. The isolated roots (2 cm) from explants inoculated with Agrobacterium and as a control, adventitious roots achieved from tissue culture of T. terrestris, were excised and transferred to solid MS medium supplemented with IBA at 25 °C in the dark. Consequently, in order to provide the possibility for large-scale culture of hairy roots for production of secondary metabolite, the hairy roots were cultured in liquid MS medium. The effect of auxins on root growth was determined by subculturing 200 mg roots from 1 month-old cultures to 250 ml flask containing 50 ml MS basal liquid medium with 2 mg L−1 IBA in transformed and control roots. Flasks were placed on a horizontal shaker (90–110 rpm) in the dark at 25 °C. Growth rates of hairy roots were determined by monitoring the fresh weight for 50 days. The medium was replaced every 2 weeks. Three replicates were done for each observation. These root cultures were used for secondary metabolite analysis.

Extraction and measurement of ß- carboline alkaloids

The dried powdered natural plant material (fruit, leaves and roots), callus culture, and transgenic hairy roots were used for obtaining the crude extract by soaking 1 g of dried biomass in 50 ml methanol at 50 °C in water bath for 1 h. The extracts were combined and evaporated to dryness. The residue was dissolved in 50 ml HCl (2 %) and filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. The filtrate was extracted twice with 20 ml petroleum ether. The aqueous acid layer was then made alkaline (pH 10) using NH4OH and extracted four times with 50 ml chloroform. The resulting chloroform layer was combined and evaporated to dryness, and the residues were dissolved in 3 ml methanol (Kartal et al. 2003). The extracts obtained above were then passed through a 0.45-μm filter and 10 μl of the filtrate extract was directly injected into the HPTLC column made of aluminum sheets of silica gel 60 F254 (Merck). CAMAG analytical HPTLC system was used for estimation of ß-carboline alkaloid (Switzeland-Swiss confederation). Harmine (Sigma Chemicals) and harmaline (Sigma Chemicals) were used as standards. The chromatograms were developed in the mobile phase chloroform: methanol: 25 % ammonia—8.4:1.4:0.2. Different extracts were injected into HPTLC apparatus to determine the content of harmine and harmaline. Samples were spotted on precoated TLC plates using an applicator. The ascending mode was used for development of thin layer chromatography. TLC plates were developed up to 8 cm and then, the plate were air dried and scanned under UV319 nm and UV374 nm. The contents of harmine in the samples were determined by comparing the area of the chromatogram with calibration curve of the working standard of harmine.

Regeneration of transformed roots

To induce callus and adventitious shoot formation, 2–3 cm transgenic hairy root obtained from A. rhizogenes strain AR15834 was transferred into the MS medium with (0, 2 mg L−1) BAP and (0, 0.1 and 0.4 mg L−1) NAA in combination with 100 mg L−1 caseain hydrolysate. The flasks were then kept at 25 °C under a 16-h photoperiod with a light intensity of 40 μmol m−2 s−1.

Statistical analysis

The transformation experiments for T. terrestris were evaluated by two Agrobacterium rhizogenes strains and four culture media in a factorial arrangement based on completely randomized design. Each treatment consisted of 15 explants per Petridish with three replicates. The analysis of variance was done and means comparison was conducted by using Duncan’s multiple range test at p = 0.01. All the calculations concerning the quantitative analysis were performed, with external standardization, by the measurement of peak areas.

Results

Callus derived hypocotyl, leaf and epicotyl segments when co-cultivated with A. rhizogenes for induction of hairy root, most of the callus segments died on media with MS salt and cefotaxime within 15 days while most of the calli and epicotyl explants showed necrosis. Only explants derived from the leaves survived and did not show any visible signs of necrosis and thus were used for further study. Emerging hairy roots were not observed for the non transformed (control) explants in medium without any PGRs. But at the same condition after 10–14 days, hairy roots began appearing at the cut surface of transformed (infected) explants (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Hairy roots of T. terrestis obtained from leaf explants transformed with A. rhizogenes strain AR15834 exhibiting during growth on MS medium after 28 days

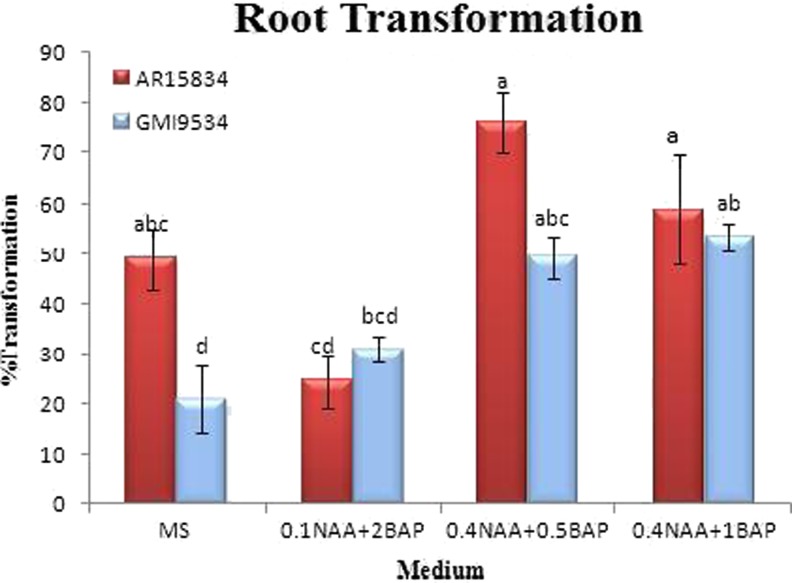

Statistical analysis using analysis of variance (ANOVA) showed a significant difference among media and strains and their interactions (P < 0.01) (Table 1). The number of roots produced on selective medium to the number of cultured explants was determined and it was found that the highest percentage of putative transformed hairy roots was achieved on (MS +350 mg L−1 cefotaxime) i.e. 49 % and 22 % for AR15834 and GMI9534 strains, respectively (Fig. 1). However, MS medium supplemented with NAA and BAP combination resulted into optimum percentage of transformation for AR15834 and GMI9534 on MS +0.4 mg L−1 NAA +0.5 mg L−1 BAP (78 %) and MS +0.4 mg L−1 NAA +1 mg L−1 BAP (53 %), respectively (Fig. 2).

|

Table 1.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for root transformation of Tribulus terrestris

| S.O.V | df | MS (mean square) |

|---|---|---|

| Medium(A) | 3 | 1654.48** |

| Strain (B) | 1 | 1080.40** |

| Medium × Strain (A × B) | 3 | 421.81* |

| Error | 16 | 111.29 |

| CV = 21.2 % |

S.O.V stands for source of variation, and df stands for degree of freedom, and CV stands for coefficient of variance

* and **Significant at the 0.05 and 0.01 probability levels, respectively

Fig. 2.

Mean comparison among medium and Agrobacterium strain interaction on percentage of root transformation of T. terrestris which analyzed by Duncan’s multiple range test. Each value represents the mean±SE from three independent experiments which carried out with three replication, each using 15 explants (Leaves). Mean values within a column followed by a different letters are significantly different at p≤0.01 probability level

One of the important results of the present study was the emergence of hairy roots on medium without adding PGRs, most of the isolated putative transformed roots showed vigorous elongation with lateral roots on hormone-free medium.

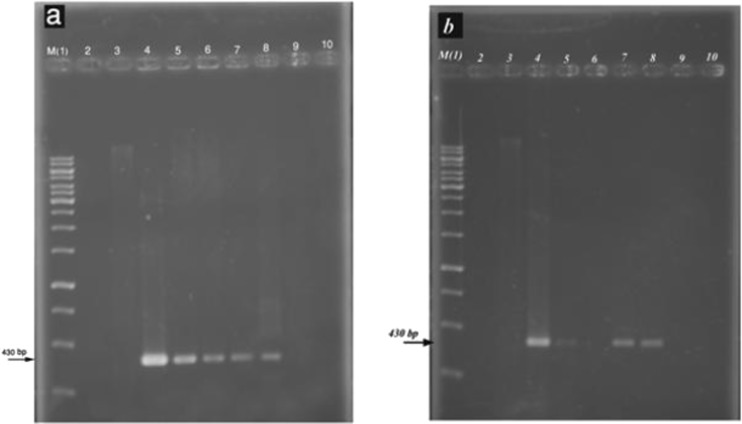

Furthermore, the appearance of hairy roots at the site of inoculation was the first sign of successful infection by A. rhizogenes although some of hairy roots might have escaped and probably remained non-transformed and thus, we confirmed the transformants by PCR using gene-specific primers also. Hairy roots were made bacteria-free by transferring them to fresh medium containing the antibiotics mentioned above for every 2 weeks. Also, all hairy root clones were checked for Agrobacterium contamination by culturing hairy root sample on LB medium. The putative transgenics which were grown on selectable medium containing antibiotic was first checked for the presence of Ri plasmid (escaped bacteria) with PCR via vir C gene primers. Then, the putative lines with no positive band were screened and checked by PCR for presence of rolB gene. Genomic DNA of putative transgenic and non-transgenic (control) roots were analyzed by PCR for the presence of rolB gene using gene-specific primers. The rolB gene was amplified using specific primers yielded fragments of 430 bp, using DNA of transgenic hairy roots as template. The putative transgenic were screened and checked by PCR for specific rolB gene. However, no amplification was observed in the control hairy roots, with the primers (Fig. 3a and b). The presence of sharp bands in positive control confirmed that the specific primers were annealed with our construct properly (Fig. 3a and b Lane 4). PCR analysis of roots for AR15834 and GMI9534 strains showed that the roots contained the rol B gene with 430 bp fragment (Fig. 3a and b). To optimize the growth of transgenic hairy roots, different concentrations of IBA were added to solid and liquid medium. The untransformed roots were used as a control, and were cultured on the same strength MS medium containing 2 mg L−1 IBA and 30 g L−1 sucrose.

Fig. 3.

PCR analysis of genomic DNA from hairy roots of Tribulus terrestris on a 1.2% agarose gel a and b. Amplification of a 430 bp rolB gene fragments transformed with AR15834 and GMI9534 strains, respectively. Lane 1: DNA size marker (1Kbp ladder), Lane 2: negative control (Water), Lane 3 negative control (DNA from non-transformed plant), Lane 4: positive control (plasmid containing rolB gene), Lanes 5 to 9 DNA from roots that survived infection, respectively

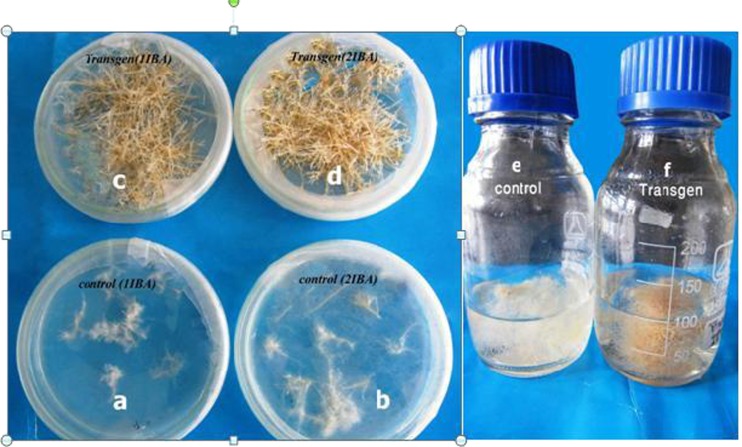

Pretreatment with IBA caused root formation in all transgenic and control roots on solid MS medium and root number and branching in the rolB lines significantly increased compared to untransformed roots (Fig. 4c, d). Control (Non-transformed roots) samples showed very slow growth, reduced elongation and rapidly turned brown (Fig. 4a, b). Also, supplementation of exogenous auxins into liquid MS medium accelerated the growth of hairy roots. A 17–18 fold increase in transgenic root biomass, (3.8 g fresh tissue) from the initial inoculum (0.2 g fresh weight) was achieved on the MS medium containing 2 mg L−1 IBA compared to the biomass of control roots (1.5 g) (Table 2 and Fig. 4e, f).

Fig. 4.

Induction and growth of transgenic hairy and control root cultures of T. terrestris on solid MS medium supplemented with different concentrations of IBA after 45 days. a 1mg L-1 IBA Control root, b 2mg L-1 IBA Control root, c 1mg L-1 IBA Transgenic root and d 2mg L-1 IBA e 2mg L-1 Control root f 2mg L-1 IBA Transgenic root

Table 2.

T-test for growth of transgenic hairy and untransformed roots of Tribulus terrestris

| Mean | N | df | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable1 (control root) | 1.5 | 6 | 5 | 3.92* |

| Variable2 (Transgenic root) | 3.8 | 6 |

* Significant at the 0.05 probability levels, and df: Stands for degree of freedom

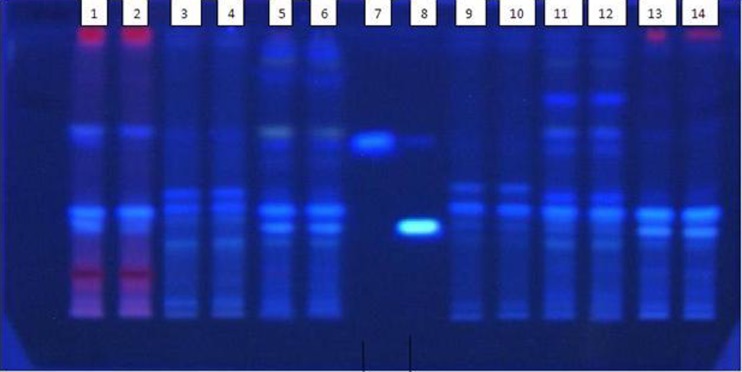

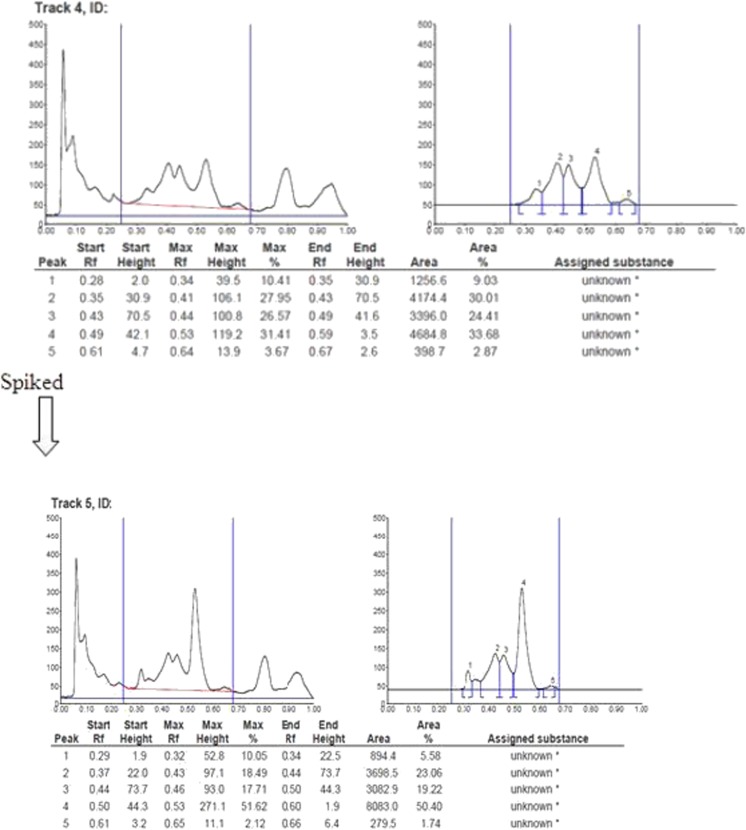

ß- Carboline alkaloid composition of the hairy root clone and a wild variety were compared by HPTLC. This includes developing TLC fingerprint profiles and estimation of chemical markers and biomarkers. The major advantage of HPTLC is that several samples can be analyzed simultaneously using a small quantity of mobile phase (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

HPTLC fingerprint profile and densitometric scanning of different parts of natural plant and transgenic hairy roots of Tribulus terrestris L. on MS medium containing IBA (Lane1 and 2 Leaves, Lane 3 and 4 Seeds, Lane 5 and 6 Natural roots, Lane7 Harmine, Lane8 Harmaline , Lane 9 and 10 Control root, Lane11 and 12 Transgenic roots, Lane 13 and 14 Callus)

In this study standards of harmaline and harmine were detected with 0.36 and 0.56 retardation factor (Rf), respectively and the peak obtained with standard harmine was used to identify the corresponding peaks in root extracts. In addition, the root extracts were spiked with standard of harmine to confirm the peaks corresponding to harmine (Fig. 6). However, the presence of harmaline in extract of different parts of natural plant and transgenic roots was not detectable by HPTLC.

Fig. 6.

Peak response of HPTLC chromatogram of extract of hairy root culture of T. terrestris spiked with standard of harmine (Peak4). Retardation factor (Rf) of harmine was 0.56 at 319nm

It was found that the content of harmine in dry samples of two month old natural plant (sample of dried roots, leaves and fruits) (in vivo condition) and extracts of 6 weeks old transgenic hairy roots were statistically significant (Table 3). The analysis of extracts showed that the maximum content of harmine was 9.7 μg/g in leaves. The transgenic hairy roots showed similar concentration of harmine (1.7 μg/g dry weight of root powder) in comparison with control roots (1.21 μg/g dry weight of root powder) (Table 4). However no statistical difference was found between (p ≤ 0.05).

Table 3.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) for harmine content of extract of different parts and transgenic hairy roots of Tribulus terrestris

| S.O.V | df | MS (mean square) |

|---|---|---|

| Within group | 5 | 94.36* |

| Eror | 12 | 0.326 |

| (CV) = 21.17 % |

*Significant at the 0.05 probability levels, and df: Stands for degree of freedom and CV: Stands for coefficient of variance

Table 4.

Comparison mean of harmine content of different parts and transgenic hairy roots of Tribulus terrestris by Duncan’s multiple range test at the 0.05 probability level

| Sample | Harmine Concentration (μg/g) | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Natural roots | 1.6 | 1.7bc |

| 1.76 | ||

| 1.8 | ||

| Leaves | 9.1 | 9.78a |

| 8.96 | ||

| 11.3 | ||

| Fruits | 1.74 | 1.73b |

| 1.84 | ||

| 1.61 | ||

| Transgenic Roots | 1.36 | 1.21b |

| 1.12 | ||

| 1.29 | ||

| Callus | 0.86 | 1.34bc |

| 1.42 | ||

| 1.73 | ||

| Root of tissue culture | 0.39 | 0.36c |

| 0.38 | ||

| 0.31 |

Value within a column followed by different letters are significantly different at the 0.05 probability level

Plant regeneration from hairy roots

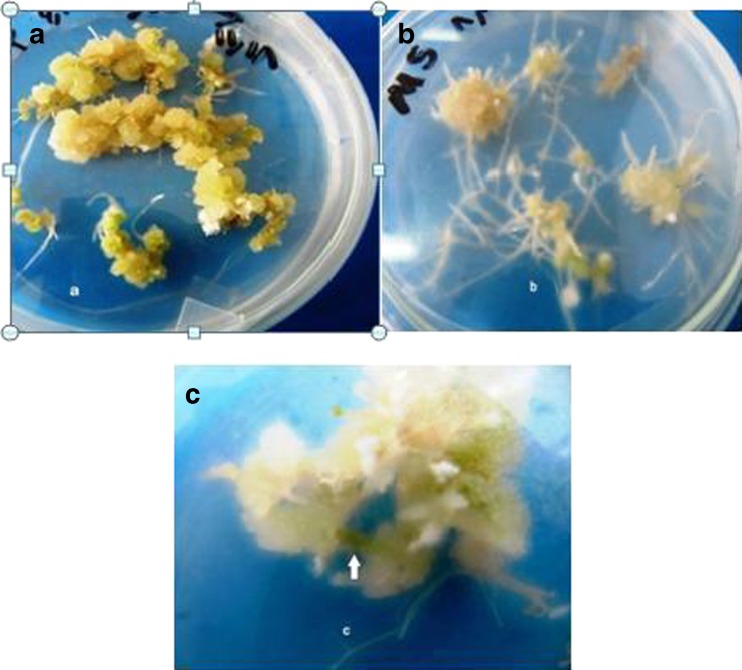

When 2–3 cm root segments excised from the positive transformed hairy root line were transferred into the callus induction medium supplemented with different concentrations of BAP and NAA, the segments of hairy roots began thickening and swelling. They formed small green calli from the cut ends after 30–40 days (Fig. 7a). A few root segments still produced new lateral roots. It was also found that hairy roots, after being cultured in growth regulator-free MS medium, continued to elongate and gradually formed new lateral roots and small white callus but untransformed (control) roots could not grow on MS medium without plant growth regulator and could not develop callus (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7.

a Callus induction and shoot regeneration from transgenic roots of T. terrestris on MS medium supplemented with 0.4mg L-1 NAA+ 2 mg L-1 BAP after 40 days. b Root induction from callus achieved from transgenic roots on MS medium without PGR. c Shoot regeneration from transgenic calii on MS medium supplemented with 0.4 mg L-1 NAA+ 2 mg L-1 BAP after 40 days

The calli induced spontaneously on 6 weeks-old root cultures transformed with A. rhizogenes strain AR15834, were excised, cultured and maintained on MS and MS supplemented with NAA and BAP under 16/8 h (light/dark) photoperiod at 25 °C.

Unorganized callus mass originated from transformed roots upon transfer to MS medium without phytohormone showed the emergence of a plenty of hairy roots and high potential of rooting. Shoots regeneration from callus of transformed roots obtained on MS medium containing 0.1 mg L−1 NAA +2 mg L−1 BAP and 0.4 mg L−1 NAA +2 mg L−1BAP through infection with Agrobacterium strain AR15834 after 40–50 days but could not develop to mature shoot and plantlet (Fig. 7c).

Discussion

Alternative methods of in vitro production of medicinal plants, such as hairy root cultures (HRC) from several important species have been developed (Guillon et al. 2006; Savitha et al. 2006). Major factors that affect on the efficiency of genetic transformation include transformation procedure, as well as Agrobacterium strain, plant species, the co-culture conditions, the genotype and explant types, hormonal state of the tissue and culture conditions were also reported (Gaudin et al. 1994; Cheng et al. 2004).

In this study, we evaluated the influence of cocultivation duration, explant types, Agrobacterium strains to optimize the root transformation. First attempts failed as the explants ceased and didn’t survive after 3 days of co-cultivation. During co-cultivation an excessive number of bacteria impose stress on plant cells, negatively affecting their regeneration potential, while use of lower number of bacteria reduce the frequency of T-DNA transfer (Montoro et al. 2003; Folta et al. 2006).

Also the choice of appropriate explants type appears to be the most important factor in enhancing transformation frequency. In several studies of gene transformation leaf explant was more suitable than other explants as we found in our case also (Wang et al. 2006; Sivanesan and Ryong Jeong 2009; Chaudhury and Pal 2010). Also, explants capable of auxin synthesis (intact shoots with shoot tips and young leaves) are expected to show higher transformation rates (Cardarelli et al. 1987).

In the present study, we observed superiority of AR15834 strain for transferring of rolB gene to Tribulus compared with GMI9534 strain in all explants. Reports are available from earlier studies also that A. rhizogenes strain 15834 is most effective strain for hairy root development in Rubia tinctorum and Catharanthus roseus. (Brillanceau et al. 1989; Ercan et al. 1999).

One of the important findings of the current study was the emergence of hairy roots from transgenic explants on medium without adding PGRs. Many reports have supported the accuracy of this result in other medicinal plants (Lu et al. 2008; Peng et al. 2008).

In this study, when we used high concentrations of NAA with BAP, the percentage of root transformation increased in comparison with MS medium without PGRs. It seems that applying higher concentrations of exogenous auxins in medium leads to the increase of adventitious hairy roots by inducing cell division in the surrounding area of the roots. Some previous reports showed that it can be the result of reduced activity of apical dominance due to high accumulation of auxins (Finlayson et al. 1996).

To confirm transformation events, putative transgenic lines were screened by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the presence of the rolB gene (Sevón and Oksman-Caldentey 2002).

The growth rate of transgenic hairy roots was very slow and low in light (data not shown) and so as to solve this problem, we transferred these cultures to dark conditions based on previous reports indicating incubation in the dark may delay degradation of endogenous and/or exogenous plant growth regulators (Rusli and Pierre 2001). In addition, dark treatment may reduce the levels of cell wall thickness and cell wall deposits, facilitating translocation of plant growth regulators in plant cells (Herman and Hess 1963).

Our findings showed that the addition of IBA into the medium increased the growth of transgenic hairy root cultures of T. terrestris. Previous findings have showed that the addition of IBA at optimum levels enhanced the growth of hairy root culture of Echinacea but had no effect on the production of secondary metabolites (Choffe et al. 2000; Koroch et al. 2002; Staniszewska et al. 2003; Washida et al. 2004). The TL-DNA rolB gene does not increase auxin levels (Nilsson et al. 1993) but increases the sensitivity of plant cells to the growth regulator (Cardarelli et al. 1987; Shen et al. 1988; Spanó et al. 1988; Maurel et al. 1991; Welander et al. 1998), probably by enhanced binding of the auxin to plant cell membranes (Filippini et al. 1994), consequently increasing the rooting efficiency. The changes in sensitivity and content of endogenous growth regulators in plant cells undoubtedly affected the response effect of plant cells to exogenous growth regulators (He-Ping et al. 2011).

The hairy root cultures established in liquid MS medium showed high growth rates as compared to non-transformed roots and could prove to be a useful system for production of secondary metabolites present in this important medicinal Tribulus species. Similarly, several workers have also used the liquid medium to establish the hairy root growth (He-Ping et al. 2011; Pavlov et al. 2005; Romero et al. 2009; Sivanesan and Ryong Jeong 2009). Few previous studies support this idea that IBA could positively affect growth and secondary metabolism of various medicinal plants (Kim et al. 2003; Baque et al. 2010).

In the last two decades, (HPTLC) has emerged as an important tool for the qualitative, semi-quantitative and quantitative phytochemical analysis of herbal drugs and formulations. The presence of harmaline in the extract of different parts of natural plant and transgenic roots was not detectable. Even if harmaline existed in extracts, it’s content was lower than the detection limit which was used in this method. The study of HPTLC method by Madadkar Sobhani et al. (2001) showed the presence of minor amount of harmine in pure sample of harmaline prepared from Sigma company. These findings suggested the hypothesis that in normal environment condition, harmaline can convert progressively to harmine.

Most of the works on alkaloid production have been carried out in cell suspension and hairy root culture (Berlin et al. 1989; Kim et al. 1994; Bhadra et al. 1993; Batra et al. 2004). In our experiments, Tribulus hairy roots induced by A. rhizogenes showed vigorous growth and produced equal amounts or more harmine than non-transformed roots and they may have a better root yield than the roots of non-transformed plants. Increasing root yield is of special importance in Tribulus terrestris because root growth is very slow and consequently highly expensive to maintain. In addition, plant regeneration from hairy roots may be a means for producing transformed Tribulus plants, in particular with respect to increasing the root yield. However, there has been no report till now on plant regeneration from hairy roots of T. terrestris. One explanation for the fact that transformed roots of T. terrestris exhibited low harmine contents is that these roots were unable to interact with other plant tissues/organs leading to the biosynthesis of harmine. The production of certain secondary metabolites requires participation of roots and leaves. Metabolic precursors produced by organ-specific enzymes in roots are presumed to be translocated to aerial parts of the plant for conversion to another product by the leaves. A solution to this problem is the root-shoot co-culture using hairy roots and their genetically transformed shoot counterparts shooty teratomas (Subroto et al. 1996; Mahagamasekera and Doran 1998).

Hairy root cultures of Oxalis tuberose transformed with A. rhizogenes (ATCC-15834) showed better growth and exudation of harmine and harmaline in comparison to untransformed control roots. Harmine and Harmaline showed wide constitutive antimicrobial activity against soil-borne microorganisms (Bais et al. 2003), anti-leishmanial activity (Di Giorgio et al. 2004), bioinsecticidal activity (Rharrabe et al. 2007), and cytotoxic to cancer cells (Rivas et al. 1999). HPLC analysis of hairy roots clones of Hyoscyamus and Persian poppy of Papaver bracteatum L. showed that the relative concentration of alkaloids were virtually identical in wild-type and transgenic roots. But the transgenic roots grew faster than wild type (Flores et al. 1987; Park and Facchini 2000). In our study, the content of harmine in the transformed roots is identical to natural roots, but the production of secondary metabolite may have increased due to rapid accumulation of a considerable root mass by continuous and active growth of roots in in vitro condition.

We have observed spontaneous dedifferentiation of transformed roots to callus on phytohormone free basal media which is similar to reports available from several species of Solanaceae (Jaziri et al. 1994; Moyano et al. 1999, 2003; Batra et al. 2004). Bandyopadhyay et al. (2007) have reported spontaneous dedifferentiation in LBA9402-transformed hairy roots of Withania somnifera. The probable cause of dedifferentiation could be the combined effective increase of plant growth regulators auxin and cytokinin in transformed roots of such species (Pitta-Alverez and Giulietti 1995). A previous study by Sharifi et al. (2012) showed optimum shoot regeneration obtained from epicotyl and hypocotyl explants of T. terrestris on MS medium supplemented with 0.1 mg L−1 NAA +2 mg L−1 BAP and 0.4 mg L−1 NAA +2 mg L−1 BAP respectively. Upon transfer to the mentioned medium, shoot regeneration from callus of transformed roots were obtained in these cultures after 40–50 days but they could not develop to mature shoots. It seems that the concentration of cefotaxime is not toxic to the explants, there might be an interaction between the explant and the bacteria which negatively affects shoot regeneration (Maurel et al. 1991; Welander et al. 1998).

Thus, plants can be regenerated from hairy root cultures either spontaneously (directly from roots) or by transferring roots to hormone-containing medium. The successful regeneration of transgenic plants requires two major factors: an efficient regeneration system and an effective method for the integration of genes into the DNA of plant cells (Hansen and Wright 1999).

Conclusion

The present study is the first report on the genetic root transformation of T. terrestris. There is variability in transformation percentages due to differences in Agrobacterium strains and medium composition. In both liquid and solid media, transgenic hairy root cultures exhibited vigorous growth in compared with control roots and accumulated harmine at the same levels as the control roots. These transgenic hairy roots can be taken for bioreactor cultures, thus favorable for production of specific medicinal products (Design of a large-scale bioreactor) for harmine production should be feasible based on these results. In the present experiments the plant regeneration from hairy roots was a limiting factor of the transformation method and could be improved in future experiments. An improved understanding of the biochemical pathways leading alkaloides synthesis will, in turn, be exploitable in manipulating and maximizing product synthesis under tissue culture and, ultimately, bioreactor conditions. Increase in product content of hairy roots by manipulation of the culture medium as well as precursor additions or elicitation would be experimented for increasing harmine content in hairy root cultures of T. terrestris. The present study also opens up a way to isolate and characterize other compounds present in T. terrestris roots and to determine their biological activity using suitable assay systems.

Abbreviations

- BAP

6-Benzylaminopurine

- IBA

Indol-3-Butyric Acid

- NAA

Naphthaleneacetic Acid

- rolB

Root locus B

- PCR

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- Rf

Retardation factor

- HPTLC

High Performance Thin Layer Chromatograghy

References

- Bais HP, Vepachedu R, Vivanco JM. Root specific elicitation and exudation of fluorescent β-carbolines in transformed root cultures of Oxalis tuberosa. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2003;41:345–353. doi: 10.1016/S0981-9428(03)00029-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay M, Jha S, Tepfer D. Changes in morphological phenotypes and withanolide composition of Ri-transformed roots of Withania somnifera. Plant Cell Rep. 2007;26:599–609. doi: 10.1007/s00299-006-0260-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baque MA, Hahn EJ, Paek KY. Growth, secondary metabolite production and antioxidant enzyme response of Morinda citrifolia adventitious root as affected by auxin and cytokinin. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2010;4:109–116. doi: 10.1007/s11816-009-0121-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batra J, Dutta A, Singh D, Kumar S, Sen J. Growth and terpenoid indole alkaloid production in Catharanthus roseus hairy root clones in relation to left- and right- termini- linked Ri T-DNA gene integration. Plant Cell Rep. 2004;23:148–154. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0815-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin J, Martin B, Nowak J, Witte L, Wray V, Strack D. Effect of permeabilization on the biotransformation of phenylalanine by immobilized tobacco cell cultures. Z Naturforsch N Sect C Biosci. 1989;44c:249–254. [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra R, Vani S, Shanks JV. Production of indole alkaloids by selected hairy root lines of Catharanthus roseus. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1993;41:581–592. doi: 10.1002/bit.260410511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgaud F, Gravot A, Milesi S, Gontier E. Production of secondary metabolites: a historical perspective. Plant Sci. 2001;161:839–851. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9452(01)00490-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brillanceau MH, David C, Tempe J. Genetic transformation of Catharanthus roseus G. Don by Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Plant Cell Rep. 1989;8:63–66. doi: 10.1007/BF00716839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA (1998) Gene Cloning. Blackwell Science LTD. 3rd edition:50–56

- Cardarelli M, Spano L, Mariotti D, Mauro ML, Slyus V, Constantino P. The role of auxin in hairy root induction. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;208:457–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00328139. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury A, Pal M. Induction of shikonin production in hairy root cultures of Arnebia hispidissima via Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated genetic transformation. J Crop Sci Biotechnol. 2010;13(2):99–106. doi: 10.1007/s12892-010-0007-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M, Lowe BA, Spencer TM, Ye X, Armstrong CL. Factors influencing Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of monocotyledonous species. In Vitro Cell Dev Plant. 2004;40:31–45. doi: 10.1079/IVP2003501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choffe KL, Murch SJ, Saxena PK. Regeneration of Echinacea purpurea: induction of root organogenesis from hypocotyl and cotyledon explants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2000;62:227–234. doi: 10.1023/A:1006444821769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giorgio C, Delmas F, Ollivier E, Elias R, Balansard G, Timon Davida P. In vitro activity of the β-carboline alkaloids harmane, harmine, and harmaline toward parasites of the species Leishmania infantum. Exp Parasitol. 2004;106:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eibl R, Eibl D. Design of bioreactors suitable for plant cell and tissue cultures. Phytochem Rev. 2008;7:593–598. doi: 10.1007/s11101-007-9083-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ercan AG, Taskin KM, Turget K, Yuce S. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated hairy root formation in some Rubia tinctorum L. populations grown in Turkey. Turk J Bot. 1999;23:373–377. [Google Scholar]

- Erhun WO, Sofowora A. Callus induction and detection of metabolites in Tribulus terrestris L. J Plant Physiol. 1986;123:181–186. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(86)80139-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filippini F, Lo Schiavo F, Terzi M, Constantino P, Trovato M. The plant oncogene rolB alters binding to auxin to plant cell membranes. Plant Cell Physiol. 1994;35:767–771. [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson SA, Liu JH, Reid DM. Localization of ethylene biosynthesis in roots of sunflower seedlings. Physiol Plant. 1996;96:36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1996.tb00180.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flores HE, Hoy MW, Pickard JJ. Secondary metabolites from root culture. Trends Biotechnol. 1987;5:67–69. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(87)80013-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Folta KM, Dhingra A, Howard L, Stewart P, Chandler CK. Characterization of LF9, an octoploid strawberry genotype selected for rapid regeneration and transformation. Planta. 2006;224:1058–1067. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0278-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudin V, Varin T, Jouanin L. Bacterial genes modifying hormonal balances in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 1994;32:11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Georgiev MI, Pavlov AI, Bley T. Hairy root type plant in vitro systems as sources of bioactive substances. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74:1175–1185. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-0856-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giri A, Narasu ML. Transgenic hairy roots: recent trends and applications. Biotechnol Adv. 2000;18:1–22. doi: 10.1016/S0734-9750(99)00016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillon S, Trémouillaux-Guiller J, Pati PK, Rideau M, Gantet P. Hairy root research: recent scenario and exciting prospects. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2006;9:341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen G, Wright MS. Recent advances in the transformation of plants. Trends Plant Sci. 1999;4:226–231. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(99)01412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He-Ping S, Yong-Yue L, Tie-Shan S, Eric TPK. Induction of hairy roots and plant regeneration from the medicinal plant Pogostemon cablin. Plant Cell Tiss Org. 2011;107:251–260. doi: 10.1007/s11240-011-9976-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herman DE, Hess CE. The effect of etiolation upon the rooting of cuttings. Proc Int Plant Propag Soc. 1963;13:42–62. [Google Scholar]

- Hu ZB, Du M. Hairy root and its application in plant genetic engineering. J Integr Plant Biol. 2006;48(2):121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2006.00121.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaziri M, Homes J, Shimomura K. An unusual root tip formation in hairy root tip culture of Hyoscyamus muticus. Plant Cell Rep. 1994;13:349–352. doi: 10.1007/BF00232635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jit S, Nag TN. Antimicrobial principles from in vitro tissue culture of Tribulus alatus. Indian J Pharm Sci. 1985;47:101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kartal M, Altun ML, Kurucu S. HPLC method for the analysis of harmol, harmalol, harmine and harmaline in the seeds of Peganum harmala. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2003;31(2):263–269. doi: 10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00568-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SW, Jung KH, Kwak SS, Liu JR. Relationship between cell morphology and indole alkaloid production in suspension cultures of Catharanthus roseus. Plant Cell Rep. 1994;14:23–26. doi: 10.1007/BF00233292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Wyslouzil BE, Weathers PJ. Secondary metabolism of hairy root cultures in bioreactors. In Vitro Cell Dev Plant. 2002;38:1–10. doi: 10.1079/IVP2001243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS, Hahn EJ, Yeung EC, Paek KY. Lateral root development and saponin accumulation as affected by IBA or NAA in adventitious root cultures of Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer. In Vitro Cell Dev Plant. 2003;39:245–249. doi: 10.1079/IVP2002397. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kino-oka M, Nagatome H, Taya M. Characterization and application of plant hairy roots endowed with photosynthetic functions. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2001;72:183–218. doi: 10.1007/3-540-45302-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koroch A, Juliani HR, Kapteyn J, Simon JE. In vitro regeneration of Echinacea purpurea from leaf explants. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2002;69:79–83. doi: 10.1023/A:1015042032091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HY, Liu JM, Zhang HC, Yin T, Gao SL (2008) Ri-mediated transformation of Glycyrrhiza uralensis with a squalene synthase gene (GuSQS1) for production of glycyrrhizin. Plant Mol Biol Rep 26:1–11

- Madadkar Sobhani A, Rahbar Roshandel N, Ebrahimi SA, Hoormand M, Mahmudian M. Cytotoxicity of Peganum harmala L. seeds extract and its relationship with contents of β-carboline alkaloids. J Iran Univ Med Sci. 2001;8(26):432–438. [Google Scholar]

- Mahagamasekera MGP, Doran PM. Intergeneric co-culture of genetically transformed organs for the production of scopolamine. Phytochem. 1998;47:17–25. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00551-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel C, Barbier-Brygoo H, Spena A, Tempe J, Guern J. Single rol genes from the Agrobacterium rhizogenes TL-DNA alter some of the cellular responses to auxin in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Physiol. 1991;97:212–216. doi: 10.1104/pp.97.1.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra BN, Ranjan R. Growth of hairy-root cultures in various bioreactors for the production of secondary metabolites. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2008;49:1–10. doi: 10.1042/BA20070103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoro P, Rattana W, Pujade-Renaud V, Michaux-Ferrieere N, Monkolsook Y, Kanthapura R, Adunsadthapong S. Production of Hevea brasiliensis transgenic embryogenic callus lines by Agrobacterium tumefaciens: roles of calcium. Plant Cell Rep. 2003;21:1095–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00299-003-0632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano E, Fornale S, Palazon J, Cusido RM, Bonfill M, Morales C, Pinol MT. Effect of Agrobactrium rhizogenes T-DNA on alkaloid production in Solanaceae plants. Phytochem. 1999;52:1287–1292. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(99)00421-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moyano E, Jouhikainen K, Tammela P, Palazòn J, Cusidò RM, Piñol MT, Teeri TH, Oksman-Caldentey KM. Effect of pmt gene overexpression on tropan alkaloid production in transformed root culture of Datura metel and Hyoscyamus muticus. J Exp Bot. 2003;54(381):203–211. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erg014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15:473–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MG, Thampson WF. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucl Acid Res. 1980;8:4321–4325. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.19.4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikam TD, Ebrahimi MA, Patil VA. Embryogenic callus culture of Tribulus terrestris L. a potential source of harmaline, harmine and diosgenin. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2009;3:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s11816-009-0096-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson O, Crozier A, Schmlling G, Olsson O. Indole-3-acetic acid homeostasis in transgenic tobacco plants expressing the Agrobacterium rhizogenes rolB gene. Plant J. 1993;3:681–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.1993.00681.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbbaumer P, Kapetanidis I, Christen P. Hairy roots of Datura candida × D. aurea: effect of culture medium composition on growth and alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant Cell Rep. 1998;17:405–409. doi: 10.1007/s002990050415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SU, Facchini PJ. Agrobacterium rhizogenes-mediated transformation of opium poppy, Papaver somniferum L., and California poppy, Eschscholzia californica Cham., root cultures. J Exp Bot. 2000;347:1005–1016. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/51.347.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov A, Georgiev V, Ilieva M. Betalain biosynthesis by red beet (Beta vulgaris L.) hairy root culture. Process Biochem. 2005;40:1531–1533. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2004.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng CX, Gong JS, Zhang XF, Zhang M, Zheng SQ. Production of gastrodin through biotransformation of P-hydroxybenzyl alcohol using hairy root cultures of Datura tatula L. Afr J Biotechnol. 2008;7(3):211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Pitta-Alverez SI, Giulietti AM. Advantages and limitations in the use of hairy root cultures for the production of tropane alkaloids: use of anti auxins in the maintenance of normal root morphology. In Vitro Cell Dev Plant. 1995;31:215–220. doi: 10.1007/BF02632025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rharrabe K, Bakrim A, Ghailani N, Sayah F. Bioinsecticidal effect of harmaline on Plodia interpunctella development (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2007;98:137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2007.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes MJC, Parr AJ, Giulietti A, Aird ELH. Influence of exogenous hormone on the growth and secondary metabolite formation in transformed root cultures. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 1994;38:143–151. doi: 10.1007/BF00033871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas P, Cassels BK, Morello A, Repetto Y. Effects of some β-carboline alkaloids on intact Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes. Comp Biochem Physiol C. 1999;122:27–31. doi: 10.1016/s0742-8413(98)10069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero FR, Delate K, Kraus GA, Solco AK, Murphy PA, Hannapel DJ. Alkamide production from hairy root cultures of Echinacea. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2009;45:599–609. doi: 10.1007/s11627-008-9187-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rusli I, Pierre CD. Factor controlling high efficiency adventitious bud formation and plant regeneration from in vitro leaf explants of roses (Rose hybrida L.) Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 2001;88:41–57. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4238(00)00189-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarwat M, Das S, Srivastava PS. Analysis of genetic diversity through AFLP, SAMPL, ISSR and RAPD markers in Tribulus terrestris, a medicinal herb. Plant Cell Rep. 2008;27:519–528. doi: 10.1007/s00299-007-0478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitha BC, Thimmaraju R, Bhagyalakshmi N, Ravishankar GA. Different biotic and abiotic elicitors influence betalain production in hairy root cultures of Beta vulgaris in shake-flask and bioreactor. Process Biochem. 2006;41:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2005.03.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Selvam ABD. Inventory of vegetable crude drug samples housed in Botanical Survey of India, Howrah. Pharmacogn Rev. 2008;2(3):61–94. [Google Scholar]

- Sevón N, Oksman-Caldentey KM. Agrobacterium rhizogenes- mediated transformation: root cultures as a source of alkaloids. Planta Med. 2002;68:859–868. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-34924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks JV, Bhadra R, Morgan J, Rijhwani S, Vani S. Quantification of metabolites in the indole alkaloid pathways of Catharanthus roseus: implications for metabolic engineering. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;58:333–338. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19980420)58:2/3<333::AID-BIT35>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi S, Nejad Sattari T, Zebarjadi AR, Majd A, GHasempour HR. Enhanced callus induction and high-efficiency plant regeneration in Tribulus terrestris L., an important medicinal plant. J Med Plant Res. 2012;6(27):4401–4408. [Google Scholar]

- Shen WH, Petitt A, Guem J, Tempe J. Hairy roots are more sensitive to auxin than normal roots. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1988;85:3417–3421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.10.3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivanesan I, Ryong Jeong B. Induction and establishment of adventitious and hairy root cultures of Plumbago zeylanica L. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8(20):5294–5300. [Google Scholar]

- Spanó L, Mariotti D, Cardarelli M, Branca C, Constantino P. Morphogenesis and auxin sensitivity of transgenic tobacco with different complements of Ri T-DNA. Plant Physiol. 1988;87:479–483. doi: 10.1104/pp.87.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staniszewska I, Królicka A, Malinski E, Lojkowska E, Szafranek J. Elicitation of secondary metabolites in in vitro cultures of Ammi majus L. Enzym Microb Technol. 2003;33:565–568. doi: 10.1016/S0141-0229(03)00180-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subroto MA, Kwok KH, Hamill JD, Doran PM. Co-culture of genetically transformed roots and shoots for synthesis, translocation and biotransformation of secondary metabolites. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1996;49:481–494. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19960305)49:5<481::AID-BIT1>3.3.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepfer D. Genetic transformation of several species of higher plants by Agrobacterium rhizogenes: phenotypic consequences and sexual transmission of the transformed genotype and phenotype. Cell. 1984;37:959–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90430-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepfer D, Tempe J. Production d’agropine par des raciness transformees sousl’action d’ Agrobacterium rhizogenes soucheA44. C R Acad Sci III (sciences de la vie) 1981;292:153–156. [Google Scholar]

- Toivonen L. Utilization of hairy root cultures for production of secondary metabolites. Biotechnol Prog. 1993;9:12–20. doi: 10.1021/bp00019a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Zhang G, Zhu L, Chen L, Zhang Y. Genetic transformation of Echinacea purpurea with Agrobacterium rhizogenes and bioactive ingredient analysis in transformed cultures. Colloid Surf. 2006;53:101–104. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washida D, Shimomura K, Takido M, Kitanaka S. Auxin affected ginsenoside production and growth of hairy roots of Panax hybrid. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27:657–660. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington State Noxious Weed Control Board (2001) Puncturevine (Tribulus terrestris L.). Website: http://www.wa.gov/agr/weedboard/weed_info/puncturevine.html

- Welander M, Pawlicki N, Holefors A, Wilson F. Genetic transformation of the apple rootstock M26 with the rolB gene and its influence on rooting. J Plant Physiol. 1998;153:371–380. doi: 10.1016/S0176-1617(98)80164-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YJ, Xie SX, Zhao HF, Han D, Xu TH, Xu DM. Studies on chemical constituents of Tribulus terrestris. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2001;36:750–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafar R, Hague J. Tissue culture studies on Tribulus terrestris L. Indian J of Pharm Sci. 1990;52:102–103. [Google Scholar]