Abstract

Adiantum capillus veneris is a medicinally essential plant used for the treatment of diverse infectious diseases. The study of phytochemical and antimicrobial activities of the plant extracts against multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria and medically important fungi is of immense significance. Extracts from the leaves, stems, and roots of Adiantum capillus veneris were extracted with water, methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, and hexane and screened for their antimicrobial activity against ten MDR bacterial strains and five fungal strains isolated from clinical and water samples. Ash, moisture, and extractive values were determined according to standard protocols. FTIR (Fourier transform infrared Spectroscopy) studies were performed on different phytochemicals isolated from the extracts of Adiantum capillus Veneris. Phytochemical analysis showed the presence of flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, saponins, cardiac glycosides, terpenoids, steroids, and reducing sugars. Water, methanol, and ethanol extracts of leaves, stems, and roots showed significant antibacterial and antifungal activities against most of the MDR bacterial and fungal strains. This study concluded that extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris have valuable phytochemicals and significant activities against most of the MDR bacterial strains and medically important fungal strains.

1. Introduction

Among foremost health problems, infectious diseases account for 41% of the global disease burden along with noninfectious diseases (43%) and injuries (16%) [1]. The main reasons of these infectious diseases are the natural development of bacterial resistance to various antibiotics [2, 3]. The development of multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria takes place because of the accumulation of different antibiotic resistance mechanisms inside the same strain [2, 4]. Although, in previous decades, the pharmacological companies have produced a number of new antibiotics, but even then drug resistance has increased [5]. This situation has forced the attention of researchers towards herbal products, in search of development of better-quality drugs with improved antibacterial, antifungal, and antiviral activities [6, 7].

According to world Health Organization (WHO), 80% of the World's population is dependent on the traditional medicine [8]. Herbal plants are rich sources of safe and effective medicines [9] and are used throughout the history of human beings either in the form of plant extracts or pure compounds against various infectious diseases [10]. For the treatment of infectious diseases, different medicinal plants have been mentioned by many phytotherapy manuals because of their reduced toxicity, uncomplicated availability, and fewer side effects [11]. Various studies have been conducted worldwide to describe the antimicrobial activities of different plant extracts [12–18]. Numerous plants have been investigated for treatment of urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal disorders, and respiratory and cutaneous diseases [19].

Adiantum capillus veneris is a common fern found in pak-indian subcontinent, Mexico, western Himalaya, warmer parts of America, and other tropical and subtropical regions of the world [20, 21]. It is used as expectorant, emmenagogue, astringent, demulcent, antitussive, febrifuge, diuretic and catarrhal affections [22]. Different extracts obtained from Adiantum had shown potential antibacterial activities against Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and antifungal activity against Candida albicans [8].

For few decades, phytochemicals (secondary plant metabolites), with unidentified pharmacological activities, have been comprehensively investigated as a source of medicinal agents [23]. Thus, it is expected that phytochemicals with sufficient antibacterial efficacy will be used for the cure of bacterial infections [10]. Many phytochemicals have been found in Adiantum capillus veneris like oleananes, phenylpropanoids, flavonoids, triterpenoids, carotenoids, carbohydrates, and alicyclics [24].

The present work was therefore designed to investigate the phytochemical, antibacterial, and antifungal activities of methanol, ethanol, water, ethyl acetate, and hexane extracts of leaves, stems, and roots of Adiantum capillus veneris against MDR bacterial strains isolated from community acquired and nosocomial infections and medicinally important fungi.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material Collection and Extraction

Adiantum capillus veneris was collected from different areas of Swat and Peshawar and then identified by the Department of Botany, University of Peshawar. For the collection of different extracts, the leaves, stems, and roots were separately shadow dried by the same method of Shalini and Sampathkumar [25]. The leaves, stems, and roots were separately ground to homogenous powder. 100 g of each powder, that is, leaves, stems, and roots was soaked in 1 liter of each distilled water, methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate and hexane for 24 h at 25°C and then filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper. According to previously described methods, the filtrates were collected in separate flasks and the same process was repeated three times [26]. The filtrates, that is, crude extracts obtained were concentrated in rotary evaporator. For the isolation of pure extracts, the isolated crude extracts were resuspended in a minimum required volume of corresponding solvents and placed on the water bath (60°C) for the evaporation of extra solvents. These extracts were then preserved in separate containers for further experimentations at 5°C, according to previous methods [27].

2.2. Ash, Moisture, Extractive Values, Phytochemical Screening, and FTIR Study of Plant Extracts

Ash value of whole plant was found out by the method of Premnath et al. [28]. Moisture value of whole plant was determined by the same method as of Ashutosh et al. [29]. Extractive values of all the fifteen extracts of leaves, stems, and roots were carried out separately by the method described by Singh et al. [30]. Different types of phytochemical tests were performed for the presence of alkaloids, tannins, saponins, flavonoids, steroids, terpenoids, glycosides, and reducing sugars [31–33]. The FTIR (Fourier transform infrared Spectroscopy) model used was IR Pretige-21 (Shimadzu, Japan) with IR Solutions software [34]. FTIR spectroscopy was carried out for all the extracts in dried form by the method used by Meenambal et al. [35].

2.3. Collection and Identification of Bacterial Cultures

The bacterial samples were obtained from the laboratories of Lady Reading Hospital, Peshawar, and Pakistan council of scientific and industrial research (PCSIR), Peshawar. Bacterial species, that is, Citrobacter freundii, Escherichia coli, and Providencia species were isolated from urine samples, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus vulgaris, Salmonella typhi, Shigella, and Vibrio cholerae from water sample while Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus were isolated from pus samples. The isolated bacterial species were subcultured on selective and differential media, for example, CLED agar and MacConkey, and were identified through their specific characteristics, that is, morphological, staining, and biochemical, according to previously described methods [36].

2.4. Collection and Identification of Fungal Cultures

The fungal samples, that is, Candida albicans, Pythium, Aspergillus flavis, Aspergillus niger, and Trichoderma, were obtained from the microbiology laboratory of Abasyn University Peshawar. The collected fungal species were subcultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) and were confirmed by staining and morphological characteristics according to the standard method [37].

2.5. Assessment of Drug Resistance Pattern of the Test-Bacterial Strains

Disk diffusion method was used for measurement of the antimicrobial activity on Muller Hinton agar. The sensitivity of fourteen antibiotics was tested against the previously mentioned ten bacterial strains (Table 3) and the process was repeated for three times. All the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C [38].

Table 3.

Drug resistance pattern of the test-bacterial strains.

| S. no. | Microorganisms | Antibiotic discs with ZI (mm) representing sensitivity, while (—) representing resistance | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 AMP |

2 AMX |

3 CF |

4 CPH |

5 CIP |

6 CTX |

7 CRO |

8 CZS |

9 GEN |

10 MXF |

11 NA |

12 NOR |

13 TET |

14 TS |

||

| 1 | E. coli | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 18 | 10 | — | — | 20 | — |

| 2 | C. freundii | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 10 | — |

| 3 | K. pneumonia | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 15 | 15 | — | — | — | — | — |

| 4 | S. typhi | — | — | — | — | — | 15 | — | — | — | 10 | 9 | — | 11 | — |

| 5 | Shigella | 20 | — | — | — | 28 | 30 | — | 20 | 12 | 19 | 19 | 29 | 11 | — |

| 6 | P. vulgaris | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 20 | 13 | — | — | — | 10 | — |

| 7 | Providencia | — | — | — | — | — | 22 | 18 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| 8 | P. aeruginosa | — | — | — | — | 30 | 16 | — | 30 | 14 | 28 | — | 30 | — | 12 |

| 9 | Staph. Aureus | — | — | — | — | 30 | 25 | — | 25 | 18 | 25 | — | 30 | 12 | — |

| 10 | V. cholerae | — | — | — | — | — | 21 | 21 | — | 12 | — | 21 | — | — | — |

AMX: amoxicillin, AMP: ampicillin, CF: cefaclor, CIP: ciprofloxacin, CPH: cephradine, CTX: cefotaxime, CZS: cefoperazone-sulbactam, CRO: ceftriaxone, GEN: gentamicin, MXF: moxifloxacin, NA: naladixic acid, TET: tetracycline, NOR: norfloxacin, TS: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ZI: zone of inhibition.

2.6. Evaluation of Antimicrobial Activity of Extracts

For the assessment of antimicrobial activities of all the fifteen extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris, the well diffusion method of Janovska et al. [39] was followed with some modifications. One mg of plant extract was dissolved in 1 mL of DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide). Preautoclaved Muller Hinton agar plates were inoculated with a 10−5 dilution of bacterial cultures with sterile cotton swabs, for uniform growth. To test the activity of plant extracts, sterile cork borer was used to bore wells in the agar. 60 μL of each extract, that is, LW (leaves water), LM (leaves methanol), LE (leaves ethanol), LEA (leaves ethyl acetate), LH (leaves hexane), SW (stem water), SM (stem methanol), SE (stem ethanol), SEA (stem ethyl acetate), SH (stem hexane), RW (root water), RM (root methanol), RE (root ethanol), REA (root ethyl acetate), and RH (root hexane), was introduced through micropipette aseptically into distinctively marked wells in the agar plates. All the plates were incubated for 24 h at 37°C and the process was repeated thrice.

2.7. Antifungal Activity of Plant Extracts

Well diffusion method of Mbaveng et al. [40] was used for the evaluation of antifungal activities of plant extracts. Preautoclaved PDA plates were inoculated with dilution of fungal cultures. 60 μL of each extract, that is, SWE, SME, SEE, SEAE, SHE, LWE, LME, LEE, LEAE, LHE, RWE, RME, REE, REAE, and RHE was introduced through micropipette aseptically into distinctively marked wells in the agar plates. All the plates were incubated for 72 h at 37°C and the process was repeated in triplicate.

3. Results

3.1. Ash, Moisture, and Extractive Value

The ash value of the whole plant was 7.81% and moisture value was 10% while extractive values were separately calculated for all the 15 extracts. LM extract had a greater percentage of extractive value (35%) followed by REA (23.6%), SM (20%), LE (20%), RE (18%), RW (17.72%), SE (16.2%), RM (16%), SEA (12%), LW (12%), LEA (10.7%), LH (8%), RH (4.32%), SW (4%), and SH (2.75%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Ash, moisture, and extractive values of fifteen extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris.

| Plant part | Solvent | Extractive value (%) | Moisture value (%) | Ash value of whole plant (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Water | 12 | 10 | 7.81 |

| Methanol | 35 | |||

| Ethanol | 20 | |||

| E. acetate | 10.7 | |||

| Hexane | 8 | |||

| Stems | Water | 4 | ||

| Methanol | 20 | |||

| Ethanol | 16.2 | |||

| E. acetate | 12 | |||

| Hexane | 2.75 | |||

| Roots | Water | 17.72 | ||

| Methanol | 16 | |||

| Ethanol | 18 | |||

| E. acetate | 23.6 | |||

| Hexane | 4.32 |

3.2. Phytochemical Screening

It is evident from Table 2 that many phytochemicals were present in Adiantum capillus veneris.

Table 2.

Phytochemicals detected in different extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris.

| Plant part | Solvent | Alkaloids | Flavonoids | Tannins | Saponins | Terpenoids | Steroids | Glycosides | Reducing sugar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Water | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Methanol | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Ethanol | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| E. acetate | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | |

| Hexane | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

|

| |||||||||

| Stems | Water | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Methanol | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Ethanol | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| E. acetate | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| Hexane | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | |

|

| |||||||||

| Roots | Water | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Methanol | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Ethanol | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| E. acetate | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | |

| Hexane | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | |

3.3. FTIR Spectroscopy

FTIR spectroscopy was used for the compound identification and run under IR region between the ranges of 400 and 4000 cm−1. The peaks (see Figures 1 to 15 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/269793) showed that the plant has compounds such as aldehyde, amides, alcohol, carboxylic acid, ketone and ethers, and so forth.

3.4. Drug Resistance Pattern of the Test-Bacterial Strains

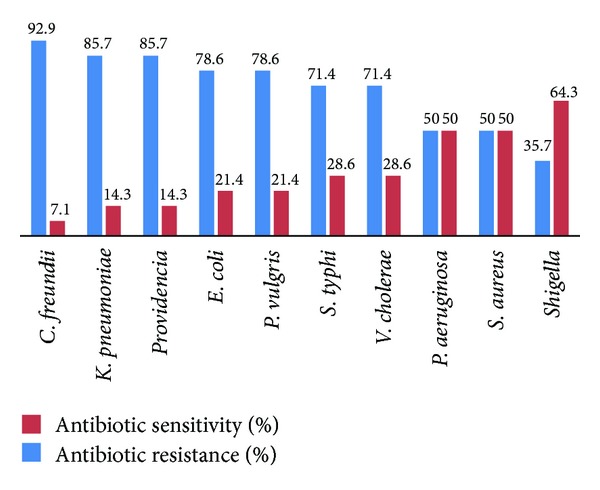

The MDR bacterial strains were tested for antibiotic sensitivity against 14 frequently used antibiotics. Most of the tested bacterial strains were found to be resistant to the used antibiotics. Citrobacter freundii was the most resistant strain (92.8%) that showed relatively low sensitivity only to tetracycline (TET) (10 mm), among all the tested organisms. Second most resistant strain (85.7%) was Klebsiella pneumoniae which showed sensitivity only to gentamicin (GEN) (15 mm) and cefoperazone-sulbactam, (CZS) (15 mm) followed by Providencia (85.7%), which showed sensitivity to cefotaxime (CTX) (22 mm) and ceftriaxone (CRO) (18 mm). Proteus vulgaris and Escherichia coli were 78.6% resistant while vibrio cholera and Salmonella typhi were 71.4% resistant to all tested antibiotics. Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus were found 50% resistant while Shigella was 35.8% resistant against all 14 test- antibiotics (Table 3).

3.5. Assessment of Antibacterial Activity of Plant Extracts

The leaves, stems and root extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris were tested against ten MDR bacterial strains. 60 μL (1 mg/1 mL) of each extract was used for antimicrobial activity estimation through well diffusion method. LM, LE, LW, SM, SE, SW, RM, RE, and RW extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris showed significant antibacterial activity against all the test bacterial strains (Table 4).

Table 4.

Antibacterial activity of fifteen extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris against various MDR bacterial strains.

| Plant part | Solvent | E. coli | Pseudomonas | Citrobacter | Klebsiella | Proteus | Vibrio | Shigella | Salmonella | S. aureus | Providencia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Water | 20 | 25 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 22 | 20 | 20 |

| Methanol | 18 | 15 | 22 | 30 | 25 | 30 | 30 | 25 | 28 | 30 | |

| Ethanol | 16 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 25 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 22 | 25 | |

| E. acetate | 15 | 15 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 15 | 20 | 0 | 15 | |

| Hexane | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Stems | Water | 20 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 12 | 15 |

| Methanol | 30 | 20 | 20 | 25 | 20 | 20 | 18 | 25 | 18 | 20 | |

| Ethanol | 30 | 25 | 18 | 25 | 25 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 18 | 20 | |

| E. acetate | 20 | 20 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 10 | 0 | |

| Hexane | 20 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Roots | Water | 25 | 22 | 25 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 18 | 10 |

| Methanol | 25 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 15 | 20 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 15 | |

| Ethanol | 25 | 20 | 20 | 16 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 20 | 15 | |

| E. acetate | 20 | 25 | 14 | 20 | 15 | 18 | 15 | 10 | 14 | 10 | |

| Hexane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Extracts with zone of inhibition (ZI) representing sensitivity in millimeter (mm).

The results were recorded after a 24-hour incubation, according to the ZI of each antibiotic for all tested bacterial strains.

3.6. Assessment of Antifungal Activity of Plant Extracts

Water, methanol, and ethanol extracts of leaves, stems, and roots of Adiantum capillus veneris showed maximum ZI against tested fungal strains while hexane extract of leaves, stems and, roots has shown no activity. LM extract has shown highest zone against Candida albicans (30 ± 1.00 mm), Aspergillus flavis (30 ± 1.00 mm), Aspergillus niger (30 ± 1.00 mm), Pythium (28 ± 1.00 mm), and Trichoderma (28 ± 1.00 mm). Similarly, LW, LE, LE, LEA, SW, SM, SEA, RW, RM, RE, and REA were also very active against most the test-fungal strains as evident from Table 5.

Table 5.

Antifungal activity of Adiantum capillus veneris extracts.

| Plant part | Solvent | Candida albicans | Trichoderma | Pythium | Aspergillus flavis | Aspergillus niger |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaves | Water | 20 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 25 |

| Methanol | 30 | 28 | 28 | 30 | 30 | |

| Ethanol | 25 | 25 | 25 | 28 | 28 | |

| E. acetate | 15 | 14 | 20 | 20 | 16 | |

| Hexane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

| ||||||

| Stems | Water | 18 | 15 | 20 | 18 | 20 |

| Methanol | 20 | 18 | 22 | 20 | 18 | |

| Ethanol | 20 | 16 | 20 | 20 | 18 | |

| E. acetate | 0 | 10 | 12 | 10 | 12 | |

| Hexane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

|

| ||||||

| Roots | Water | 25 | 22 | 25 | 20 | 22 |

| Methanol | 20 | 20 | 20 | 22 | 25 | |

| Ethanol | 20 | 18 | 18 | 25 | 20 | |

| E. acetate | 0 | 10 | 14 | 12 | 10 | |

| Hexane | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Extracts with zone of inhibition (ZI) representing sensitivity in millimeter (mm).

4. Discussion

The attention of researchers has been deviated by the increasing emergence of antibiotic resistance towards the medicinal plants in search of new, less toxic, and useful drugs. Plants are the reservoirs of valuable phytochemicals. Many plants have been investigated worldwide for their antimicrobial and phytochemical activities. Therefore, this study has been carried out to evaluate the phytochemical and antimicrobial activities of water, methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, and hexane extracts of leaves, stems, and roots of Adiantum capillus veneris.

Ash, moisture, and extractive values of all fifteen extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris were determined. Except for the ash value of whole plant which is in accordance with the study of Ahmad et al. [22], the moisture and extractive values reported in our study have not been investigated before, to the best of our knowledge.

The result of phytochemical screening of all extracts of leaves, stems, and roots of Adiantum capillus veneris showed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoides, tannins, saponins, terpenoids, steroids, glycosides, and reducing sugars (Table 2) which is in line with many other studies conducted worldwide [25, 41, 42]. FTIR results of our study have showed the presence of many new compounds, that is, aldehyde, amides, alcohol, carboxylic acid, ketone, and ethers (Figures 1–15, supplementary data), most of which are not reported previously.

In the present study, 10 bacterial strains were used which were MDR to most of the given antibiotics (Table 3). Our results showed that Citrobacter freundii was the most resistant strain (92.8%) among all the tested bacterial strains. Our findings are in line with the studies conducted in other areas of Pakistan where 100% MDR Citrobacter has been reported [43]. Additionally, 92.8% MDR Citrobacter seen in the present study is also observed in Ethiopia (100% MDR) [44] and Nepal (86.95%) [45]. Similarly, 85.7% MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae found in this study is almost in agreement with 81.8% MDR investigated locally [46] in early 2013. We investigated 85.7% MDR Providencia, almost similar to the study of Tumbarello et al. (75%) [47]. We have also investigated that Escherichia coli, P. vulgaris, Salmonella typhi, V. cholera, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Shigella are rather more MDR (Figure 1) than what was found in other regions of the world, as evident from various studies [48–50] on these bacterial strains.

Figure 1.

Percentage of antibiotic resistance and sensitivity of MDR bacterial strains.

Numerous studies on Adiantum capillus veneris showed its potency against MDR bacterial strains. For example, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Klebsiella Pneumoniae were sensitive to LW, LM, SW, and SM extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris in our study which proved to be almost in accordance with the findings of Mahboubi et al. [51] and kumar and Nagarajan [8] from Iran and India, respectively. We have found out that most of the extracts of Adiantum capillus veneris were very effective against the MDR bacterial strains as compared to other studies [52, 53] which might be due to the variation in procedures, geographical conditions, and so forth. In comparison to the antibiotics used, the plants extracts were very active against the test bacterial strains, which is evident from the comparison of Tables 3 and 4. Likewise, as compared to other studies [22, 54], all extracts except hexane used in our studies were far more effective against test-fungal strains.

The present study confirms that fractions of Adiantum capillus veneris have significant antibacterial and antifungal activity along with valuable phytochemicals. Different fractions have different antibacterial and antifungal activities against MDR bacterial and fungal strains. It is recommended that further research should be conducted for more effective outcomes.

Supplementary Material

FTIR spectroscopy was used for the compound identification and run under infra red (IR) region between the ranges of 400-4000 cm−1. The phytochemical constituents were confirmed by FTIR. The peaks showed that the plant have compounds such as Aldehyde, ketone, alcohol, carboxylic acid, amides and ethers etc. (Figures 1 to 15)

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Noumedem JAK, Mihasan M, Lacmata ST, et al. Antibacterial activities of the methanol extracts of ten Cameroonian vegetables against Gram-negative multidrug-resistant bacteria. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;13, article 26 doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chopra I. New drugs for superbugs. Microbiology Today. 2000;47:4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westh H, Zinn CS, Rosdahl VT, et al. An international multicenter study of antimicrobial consumption and resistance in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from 15 hospitals in 14 countries. Microbial Drug Resistance. 2004;10(2):160–168. doi: 10.1089/1076629041310019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harbottle H, Thakur S, Zhao S, White DG. Genetics of antimicrobial resistance. Animal Biotechnology. 2006;17(2):111–124. doi: 10.1080/10495390600957092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nascimento GGF, Locatelli J, Freitas PC, Silva GL. Antibacterial activity of plant extracts and phytochemicals on antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2000;31(4):247–256. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maiyo ZC, Ngure RM, Matasyoh JC, Chepkorir R. Phytochemical constituents and antimicrobial activity of leaf extracts of three Amaranthus plant species. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2010;9(21):3178–3182. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benkeblia N. Antimicrobial activity of essential oil extracts of various onions (Allium cepa) and garlic (Allium sativum) Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft & Technologie. 2004;37(2):263–268. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar SS, Nagarajan N. Screening of preliminary phytochemical constituents and antimicrobial activity of Adiantum capillus veneris . Journal of Research in Antimicrobial. 2012;1(1):56–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tiwari S. Plants: a rich source of herbal medicine. Journal of Natural Products. 2008;1:27–35. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parekh J, Chanda SV. In vitro antimicrobial activity and phytochemical analysis of some Indian medicinal plants. Turkish Journal of Biology. 2007;31(1):53–58. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khan R, Islam B, Akram M, et al. Antimicrobial activity of five herbal extracts against Multi Drug Resistant (MDR) strains of bacteria and fungus of clinical origin. Molecules. 2009;14(2):586–597. doi: 10.3390/molecules14020586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonjar S. Evaluation of antibacterial properties of some medicinal plants used in Iran. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2004;94(2-3):301–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam B, Khan SN, Haque I, Alam M, Mushfiq M, Khan AU. Novel anti-adherence activity of mulberry leaves: inhibition of Streptococcus mutans biofilm by 1-deoxynojirimycin isolated from Morus alba . Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2008;62(4):751–757. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almagboul AZ, Bashir AK, Farouk A, Salih AKM. Antimicrobial activity of certain Sudanese plants used in folkloric medicine. Screening for antibacterial activity (IV) Fitoterapia. 1985;56(6):331–337. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(01)00310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sousa M, Pinheiro C, Matos MEO, et al. Constituintes Químicos de Plantas Medicinais Brasileiras. Fortaleza, Brazil: Universidade Federal do Ceará; 1991. (pp. 385–388). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Artizzu N, Bonsignore L, Cottiglia F, Loy G. Studies on the diuretic and antimicrobial activity of Cynodon dactylon essential oil. Fitoterapia. 1995;66(2):174–176. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schapoval EES, Silveira SM, Miranda ML, Alice CB, Henriques AT. Evaluation of some pharmacological activities of Eugenia uniflora L. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 1994;44(3):136–142. doi: 10.1016/0378-8741(94)01178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikram M, Inamul H. Screening of medicinal plants for antimicrobial activities. Fitoterapia. 1984;55(1):62–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Somchit MN, Reezal I, Elysha Nur I, Mutalib AR. In vitro antimicrobial activity of ethanol and water extracts of Cassia alata . Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;84(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badillo VM. Lista actualizada de las especies de la familia Compuestas (Asteraceae) de Venezuela. Ernstia. 2002;11:147–215. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy BU. Enumeration of antibacterial activity of few medicinal plants by bioassay method. E-Journal of Chemistry. 2010;7(4):1449–1453. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmad A, Jahan N, Wadud A, et al. Physiochemical and biological properties of Adiantum capillus veneris: an important drug of unani system of medicines. International Journal of Current Research and Review. 2012;4(21):70–75. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krishnaraju AV, Rao TVN, Sundararaju D, et al. Assessment of bioactivity of Indian medicinal plants using Brine shrimp (Artemiasalina) lethality assay. International Journal of Applied Science and Engineering. 2005;3(2):125–134. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ansari R, Ekhlasi-Kazaj K. Adiantum capillus-veneris. L: phytochemical constituents, traditional uses and pharmacological properties: a review. Journal of Advanced Research. 2012;3(4):15–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shalini S, Sampathkumar P. Phytochemical screening and antimicrobial activity of plant extracts for disease management. International Journal of Current Science. 2012:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gracelin DHS, Britto ADJ, Kumar PBJR. Antibacterial screening of a few medicinal ferns against antibiotic resistant phytopathogen. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Research. 2012;3(3):868–873. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cannell RJP. How to approach the isolation of a natural product. Natural Products Isolation Methods in Biotechnology. 1990;4:1–52. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Premnath D, Priya JV, Ebilin SE, Patric GM. Antifungal and anti bacterial activities of chemical constituents from Heliotropium indicum Linn. Plant. Drug Invention Today. 2012;4(11):564–568. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashutosh M, Kumar PD, Ranjan MM, et al. Phytochemical screening of Ichnocarpus Frutescens plant parts. International Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemical Research. 2009;1(1):5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh S, Khatoon S, Singh H, et al. A report on pharmacognostical evaluation of four Adiantum species, Pteridophyta, for their authentication and quality control. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia. 2013;23(2) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kayani SA, Masood A, Achakzai AKK, Anbreen S. Distribution of secondary metabolites in plants of Quetta-Balochistan. Pakistan Journal of Botany. 2007;39(4):1173–1179. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Khan AM, Qureshi RA, Ullah F, et al. Phytochemical analysis of selected medicinal plants of Margalla hills and surroundings. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research. 2011;5(25):6017–6023. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayoola GA, Coker H, Adesegun SA, et al. Phytochemical screening and antioxidant activities of some selected medicinal plants used for malaria therapy in South Western Nigeria. Tropical Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2008;7(3):1019–1024. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu H, Sun S, Guang-Hua L, Kelvin KC. Study on Angelica and its different extracts by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy and two-dimensional correlation IR spectroscopy. Spectrochimica Acta A. 2006;64(2):321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meenambal M, Pughalendy K, Vasantharaja C, et al. Phytochemical information from FTIR and GC-MS studies of methol extract of Delonix elat leaves. International Journal of Chemical and Analytical Science. 2012;3(6):1446–1448. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Collee JG, Marr W. Mackie & McCartney, Practical Medical Microbiology. 14th edition. New York, NY, USA: Charchill Living Stone; 1996. Specimen collection, culture containers and media; pp. 95–111. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ainsworth GC, Sparrow FK, Sussman AC. The Fungi. An Advanced Treatise. Vol. 4. London, UK: Academic Press; 1973. (A Taxonomic Review with Keys). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ushimaru PI, da Silva MTN, di Stasi LC, Barbosa L, Fernandes A., Jr. Antibacterial activity of medicinal plant extracts. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2007;38(4):717–719. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Janovska D, Kubikova K, Kokoska L. Screening for antimicrobial activity of some medicinal plants species of traditional Chinese medicine. Czech Journal of Food Sciences. 2003;21(3):107–110. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mbaveng AT, Ngameni B, Kuete V, et al. Antimicrobial activity of the crude extracts and five flavonoids from the twigs of Dorstenia barteri (Moraceae) Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;116(3):483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajurkar NS, Gaikwad K. Evaluation of phytochemicals, antioxidant activity and elemental content of Adiantum capillus veneris leaves. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research. 2012;4(1):365–374. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakane T, Maeda Y, Ebihara H, et al. Fern constituents: triterpenoids from Adiantum capillus-veneris . Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 2002;50(9):1273–1275. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaikh D, Zaidy SAH, Shaikh K, et al. Post surgical wound infections: a study on threats of emerging resistance. Pakistan Journal Of Pharmacology. 2003;20(1):31–41. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Biadglegne F, Abera B, Alem A, Anagaw B. Bacterial isolates from wound infection and their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern in Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, North West Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Health Sciences. 2009;19:173–177. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thapa B, Karn D, Mahat K. Emerging trends of nosocomial Citrobacter species surgical wound infection: concern for infection control. Nepal Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 2010;9(1):10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hannan A, Qamar MU, Usman M, et al. Multidrug resistant microorganisms causing neonatal septicemia: in a tertiary care hospital Lahore, Pakistan. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2013;7(19):1896–1902. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tumbarello M, Citton R, Spanu T, et al. ESBL-producing multidrug-resistant Providencia stuartii infections in a university hospital. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2004;53(2):277–282. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Amaya E, Reyes D, Vilchez S, et al. Antibiotic resistance patterns of intestinal Escherichia coli isolates from Nicaraguan children. Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2011;60(2):216–222. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.020842-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimizu K, Kumada T, Hsieh W-C. Comparison of aminoglycoside resistance patterns in Japan, Formosa, and Korea, Chile, and the United States. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1985;28(2):282–288. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.2.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mirza SH, Beeching NJ, Hart CA. The prevalence and clinical features of multi-drug resistant Salmonella typhi infections in Baluchistan, Pakistan. Annals of Tropical Medicine and Parasitology. 1995;89(5):515–519. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1995.11812984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mahboubi A, Kamalinejad M, Shalviri M, et al. Evaluation of antibacterial activity of three Iranian medicinal plants. African Journal of Microbiology Research. 2012;6(9):2048–2052. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Parihar P, Parihar L, Bohra A. In vitro antibacterial activity of fronds (leaves) of some important pteridophtes. Journal of Microbiology and Antimicrobials. 2010;2(2):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bukhari I, Hassan M, Abassi FM, et al. Antibacterial spectrum of traditionally used medicinal plants of Hazara, Pakistan. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2012;11(33):8404–8406. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh M, Singh N, Khare PB, Rawat AKS. Antimicrobial activity of some important Adiantum species used traditionally in indigenous systems of medicine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2008;115(2):327–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FTIR spectroscopy was used for the compound identification and run under infra red (IR) region between the ranges of 400-4000 cm−1. The phytochemical constituents were confirmed by FTIR. The peaks showed that the plant have compounds such as Aldehyde, ketone, alcohol, carboxylic acid, amides and ethers etc. (Figures 1 to 15)