Abstract

This study demonstrated that extracellular membrane vesicles are involved with the development of resistance to fluoroquinolones by mycoplasmas (class Mollicutes). This study assessed the differences in susceptibility to ciprofloxacin among strains of Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8. The mechanisms of mycoplasma resistance to antibiotics may be associated with a mutation in a gene related to the target of quinolones, which could modulate the vesiculation level. A. laidlawii extracellular vesicles mediated the export of the nucleotide sequences of the antibiotic target gene as well as the traffic of ciprofloxacin. These results may facilitate the development of effective approaches to control mycoplasma infections, as well as the contamination of cell cultures and vaccine preparations.

1. Introduction

The suppression of mycoplasmas that infect humans, animals, and plants, as well as contaminating cell cultures and vaccines, is a serious problem [1–3]. This is because mycoplasmas rapidly acquire resistance to antibiotics. However, antibiotic therapy remains the primary tool used for the treatment of mycoplasma infections and the decontamination of cell cultures. The most widely used fluoroquinolones, which are synthetic antibacterials, are enrofloxacin, sparfloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin [3–5]. The mechanisms that facilitate the rapid development of resistance to fluoroquinolones in mycoplasmas remain unclear [6, 7]. The development of resistance to quinolones is associated with mutations in genes that encode antibiotic-targeted proteins, and a limitation is that the antibiotics used to treat microbial cells are not considered to be effective against mycoplasmas [4, 8]. Thus, it would be beneficial to elucidate the mechanisms that facilitate the rapid development of antibiotic resistance to allow the treatment of mycoplasma infections, which appear to be associated with the adaptation of mycoplasmas to stress conditions [9, 10]. The successful implementation of genome projects for a number of mycoplasmas has opened up the possibility of using postgenomic technologies to study their antibiotic resistance processes [11, 12].

A unique species of mycoplasma with adaptive properties is Acholeplasma laidlawii, which is a causative agent of phytomycoplasmoses and the main contaminant of cell cultures and vaccines [2, 13, 14]. In our study [9, 10], transcriptome-proteome analysis and nanoscopy were identified as the stress-reactive proteins and genes of Acholeplasma laidlawii, which showed that the adaptation of this mycoplasma to stressful factors was related to the production of extracellular vesicles (EVs). The EVs of bacteria are spherical nanostructures surrounded by a membrane (20–200 nm in diameter), which mediate the traffic of a wide variety of compounds that participate in signaling, intercellular interactions, and pathogenesis [15, 16]. Recent studies suggest the possible involvement of EVs in the development of resistance to antibiotics in bacteria [17, 18]. However, there are no previous studies of the roles of EVs in antibiotic resistance in mycoplasmas. Thus, the present study demonstrated the participation of A. laidlawii EVs in the development of resistance to fluoroquinolones (ciprofloxacin).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Strain and Plasmids

Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8 (from the N.F. Gamalei Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology, Moscow, Russia), clinical isolate of Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli NovaBlue strain, and plasmid vector pGEM-T Easy Vector Systems (Promega) were used in this work.

2.2. Cultivation of A. laidlawii

A. laidlawii PG8 cells were cultivated for 1 day at 37°C in Edward's medium (tryptose, 2% (w/v); NaCl, 0.5% (w/v); KCl, 0.13% (w/v); Tris base, 0.3% (w/v); serum of horse blood, 10% (w/v); fresh yeast extract, 5% (w/v); glucose solution, 1% (w/v); benzylpenicillin (500,000 IE mL−1), 0.2% (w/v)) to obtain the control cells. To obtain ciprofloxacin-resistant clones, a mycoplasma culture was grown from a single colony of the laboratory A. laidlawii PG8 strain and sequentially inoculated in a broth medium that contained increasing concentrations of the antibiotic. To determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of cells, A. laidlawii PG8R was subcultured into Edward's medium containing an appropriate concentration of ciprofloxacin. Resistant cultures of A. laidlawii PG8R were plated onto solid agar that contained appropriate concentrations of ciprofloxacin and individual colonies were analyzed.

2.3. Determination of the MIC

To determine the MIC, the original mycoplasma cell culture was passaged in broth medium with different concentrations of ciprofloxacin: 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, 1.0, and 1.5 μg mL−1. The MIC values were determined based on three independent replicates.

2.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy and Atomic Force Microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy was performed according to the method of Cole [19]. Samples were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (“Fluka,” Germany) in 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.2) for 2 h. The fixed samples were then dehydrated using an acetone, ethanol, and propylene series, before postfixing in 0.1% OsO4 with 25 mg mL−1 of saccharose. After treatment with epoxy resin (“Serva,” Switzerland), ultrathin sections were cut using an LKB-III ultramicrotome (Sweden), which were stained with uranyl acetate for 10 min and lead citrate for 10 min. The stained samples were examined using a JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope (“Joel,” Japan).

To prepare samples for atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis, 1 mL aliquots of the A. laidlawii PG8 cells and EVs were centrifuged at 12000 rpm for 20 min at room temperature. The pellets were resuspended in 1 mL of PBS × 1 (pH 7.2). The cells were centrifuged once more at 12000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature and repeatedly resuspended in 0.5 mL of the same buffer. The prepared cells were placed onto mica (Advanced Technologies Center, Moscow, Russia) where the upper layer was removed. The cells were air-dried and washed twice with redistilled water. The samples were air-dried after each wash.

AFM imaging was performed using a Solver P47H atomic force microscope (NT-MDT, Moscow, Russia), which operated in the tapping mode with fpN11S cantilevers (r ≤ 10 nm, Advanced Technologies Center, Moscow, Russia). The height, Mag (signal from lock-in amplifier), RMS (signal from RMS detector), and phase (signal from the phase detector) were set using the Nova 1.0.26 RC1 software (NT-MDT). The scan rate was 1 Hz and the image resolution was 512 × 512 pixels. Numerical data were expressed as the mean ± SE.

2.5. Accumulation of Ciprofloxacin

The presence of antibiotics in the EVs was determined using a fluorimetric method [20, 21]. The fluorescence was measured with a Fluorolog 3 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon SAS, France) at an excitation wavelength of 282 nm and an emission wavelength of 442 nm. A blank sample that contained an equivalent amount of cells without the addition of ciprofloxacin was used as a control. The results were expressed as nanograms of ciprofloxacin per milligram of protein. All of the experiments were performed at least three times to ensure reproducibility. The mean and standard error were calculated.

2.6. Antimicrobial Activity

The Kirby-Bauer disc diffusion method with a ciprofloxacin-sensitive test strain of Staphylococcus aureus was used to evaluate the bacteriostatic effects of A. laidlawii EVs [22].

2.7. Isolation of EVs

EVs were isolated from A. laidlawii cultures (logarithmic growth phase) according to the method of Kolling and Matthews, with some modifications [9, 14, 23]. The cells were precipitated by centrifugation at 5000 g for 20 min. The supernatant was filtered through a 0.10 µm filter (Sartorius Minisart, France), and the filtrate was concentrated 20-fold by ultrafiltration (Vivacell 100, 100000 MWCO, “Sartorius Stedim Biotech GmbH”, Germany). Vesicles were collected by ultracentrifugation (100000 g, 1 h, 8°C) with a MLA-80 rotor (Beckman Coulter Optima MAX-E), twice washed, resuspended in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH = 7, 4; 150 mM NaCl; 2 mM MgCl2) and filtered through a sterile filter (Sartorius Minisart, France) with a pore size of 200 nm.

2.8. Isolation of DNA from Cells and EVs

DNA was isolated from mycoplasma cells according to the method of Maniatis [24]. DNA was isolated from EVs using a commercial DNA-express kit (“Litekh,” Moscow). Before extracting the nucleic acids, the EV samples were treated with DNAse I and RNase (at 37°C for 30 min).

2.9. Sequencing

The PCR primers were constructed by NSF Litekh (Moscow, Russia) using the nucleotide sequences of A. laidlawii PG8A genes (GenBank accession number NC_010163): ftsZ (Ala1F 5′-ggtttttggatttaacgatg-3′ Ala1R 5′-gcttccgcctcttttattt-3′); spacer 16S-23S of ribosome operon (A16LF 5′-ggaggaaggtggggatgacgtcaa-3′ A23LR 5′-ccttaggagatggtcctcctatcttcaaac-3′); and parC (GenBank accession number NC_010163) (AqF15: 5′-ata cgc aat ggg aca aat g-3′; AqR15: 5′-ggt tct tgt tcc tca tca tca-3′). PCR was performed in the following regime: for primers Ala1, 95°C, 3 min (95°C, 20 sec; 52°C, 20 sec; 72°C, 20 sec) (30 cycles); 72°C, 10 min. For primers A23LR, 95°C, 3 min (95°C, 5 sec; 63°C, 5 sec; 72°C, 20 sec) (30 cycles); 72°C, 5 min. For primers Aq15, 95°C, 3 min (95°C, 5 sec; 63°C, 5 sec; 72°C, 5 sec) (35 cycles); 72°C, 5 min.

DNA sequencing was performed using BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kits (“Applied Biosystems,” USA) and a 3130 Genetic Analyzer (“Applied Biosystems,” USA). The nucleotide sequences were analyzed using the Sequencing Analysis 5.3.1 program (“Applied Biosystems,” USA) and the NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) database.

3. Results and Discussion

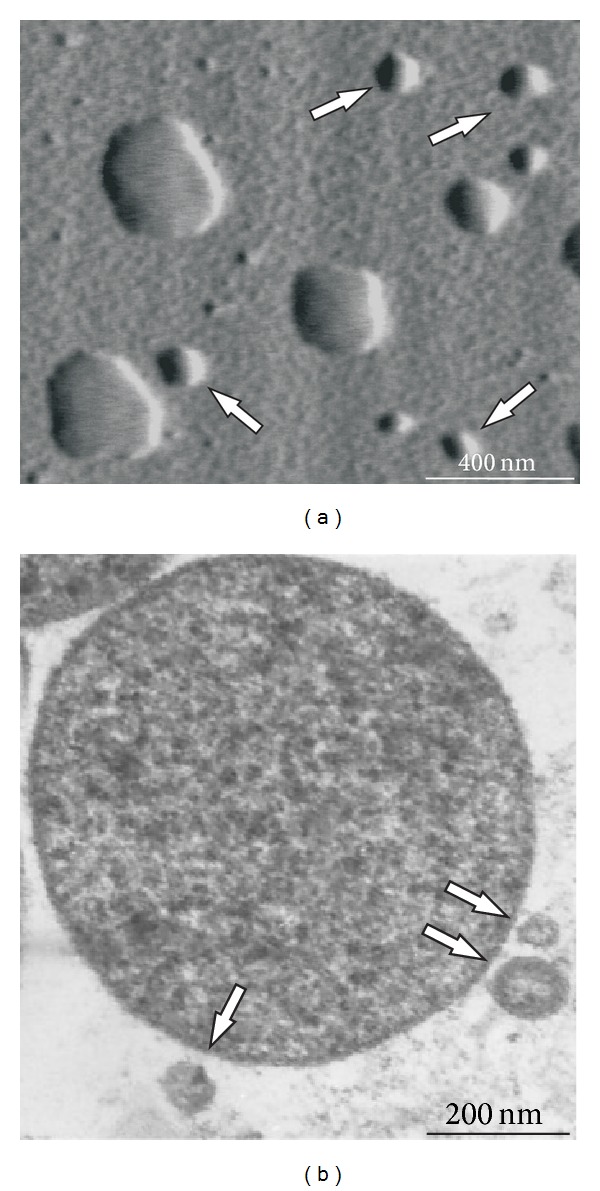

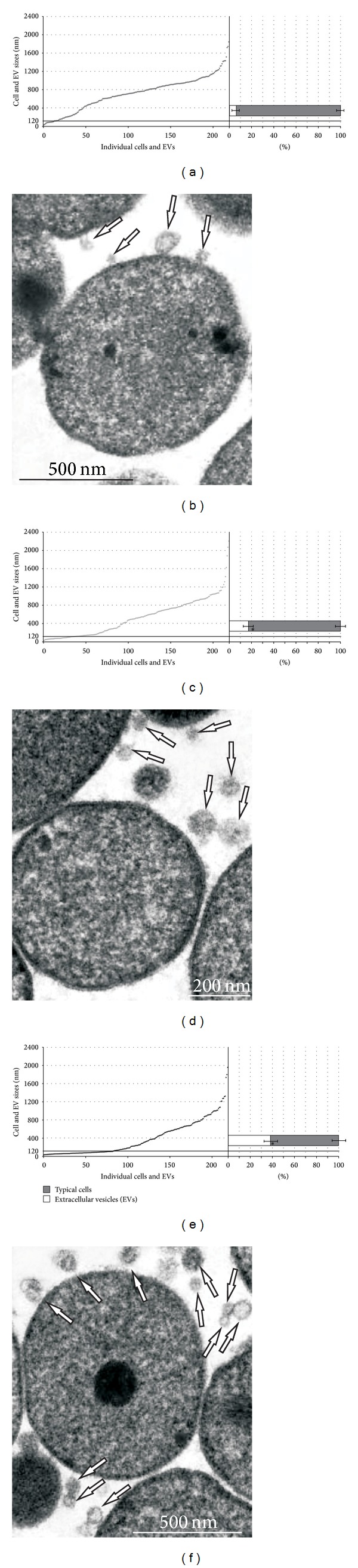

To determine the role of membrane EVs in the development of resistance to fluoroquinolones in A. laidlawii, this study used mycoplasma strains with different levels of susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, that is, PG8 (MIC 0.5 μg/mL) and PG8R (MIC 1 μg/mL). A. laidlawii strain PG8R was obtained by stepwise selection from A. laidlawii PG8. The analysis of micrographs obtained using variants of transmissive and probe microscopy showed that the mycoplasma cells secreted EVs in normal conditions (Figures 1 and 2(a)). The treatment of the mycoplasma culture with ciprofloxacin elicited a significant increase in the level of vesiculation (sixfold) (Figure 2(b)). The level of vesiculation in A. laidlawii PG8R was significantly higher than that in A. laidlawii PG8. Recently, similar results were obtained with Pseudomonas aeruginosa [25] in another study, which also showed that EVs were involved with the traffic of antibiotics, because the EVs produced by the bacterial cells contained gentamicin [26].

Figure 1.

Atomic force microscopy (a) and transmission electron microscopy (b) images of Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8 cells and extracellular vesicles (indicated by arrows).

Figure 2.

Relationships between typical cells and extracellular vesicles (EVs) (a, c, e) and transmission electron microscopy images (b, d, f) (extracellular vesicles (indicated by arrows)) of Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8 without ciprofloxacin (a, b), in the presence of antibiotic **(c, d) and A. laidlawii PG8R (e, f) (according to transmission electron microscopy). Each point corresponds to the linear size of individual cells or EVs. *P < 0.05. **Treatment with ciprofloxacin for 80 min.

The present study showed that after A. laidlawii was cultured in a medium that contained ciprofloxacin, the EVs produced by the mycoplasma contained the antibiotic (0.66 ± 0.15 ng/mg of protein). The EVs that contained ciprofloxacin also exhibited bacteriostatic effects against a clinical isolate of ciprofloxacin-sensitive S. aureus (Table 1). These results suggest that the EVs of A. laidlawii may be involved with the export of ciprofloxacin and possibly with the mechanism of mycoplasma adaptation to antibiotics.

Table 1.

Ciprofloxacin content and bacteriostatic activities of the extracellular vesicles of Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8R.

| Test samples | Ciprofloxacin (5 g/mL) | Extracellular vesicles of A. laidlawii PG8R* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native | Destroyed | ||

| Ciprofloxacin content, ng/mg of protein | — | — | 0.66 ± 0.15 |

| Lysis area (mm)** | 21.2 ± 0.3 | 3.4 ± 0.21 (P < 0.05) |

8.8 ± 0.16 (P < 0.05) |

*Mean ± standard deviation.

**Native extracellular vesicles of A. laidlawii PG8R were used as a control to estimate the bacteriostatic effects of the vesicle components.

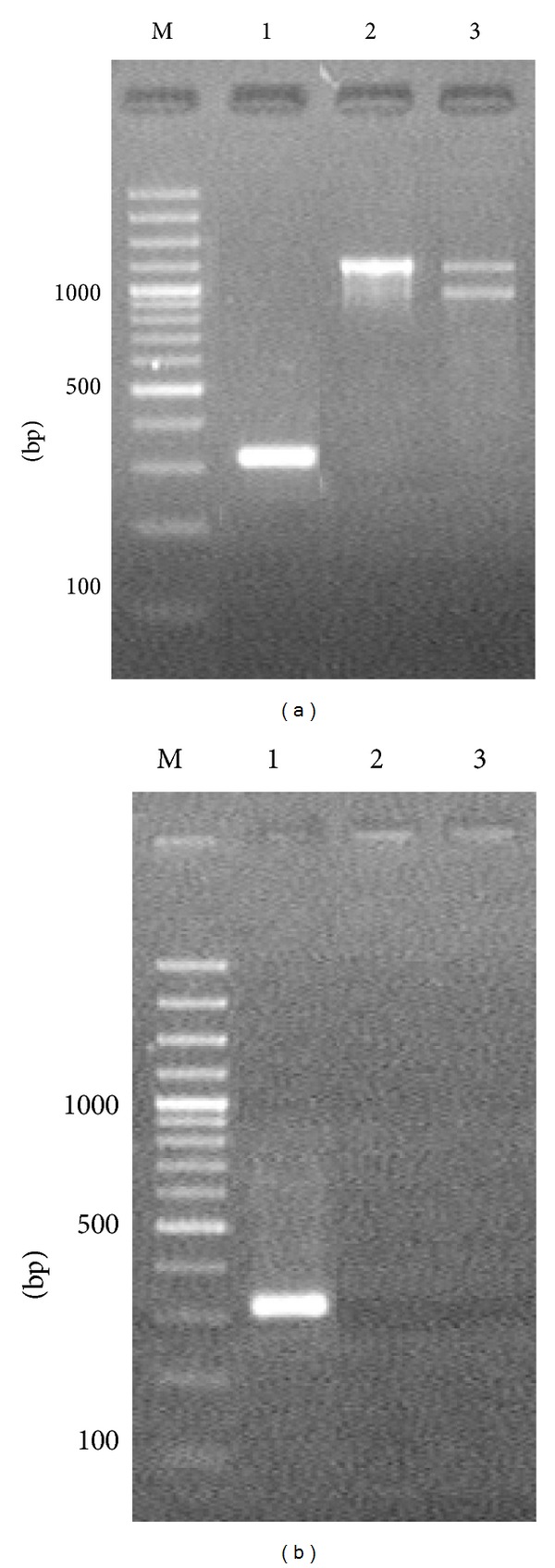

The main mechanisms that facilitate the development of resistance to quinolones in bacteria are considered to be associated with mutations in specific loci, that is, the quinolone-resistance-determining regions (QRDRs) of genes that encode antibiotic-targeted proteins [7, 27, 28]. The most significant locus is the QRDR in parC of DNA topoisomerase IV [7, 29]. To determine whether this locus was involved with the increased resistance to ciprofloxacin in A. laidlawii PG8R, the parC QRDRs of the mycoplasma strains were amplified, cloned, and sequenced. The DNA was extracted from mycoplasmas cultivated in broth culture, which were obtained from a single colony grown on solid medium. The DNA sequences isolated from the cells of A. laidlawii PG8 and A. laidlawii PG8R were not identical (Figure 3(a)). The nucleotide sequence of parC QRDR from A. laidlawii PG8R contained a C → T transition at position 272, which caused a serine to leucine (Ser (91) Leu) replacement in the amino acid sequence of the antibiotic-targeted protein (Figure 3(b)). Previously, this mutation was found in a strain of A. laidlawii PG8B, which was characterized by its elevated resistance to quinolones (6–10 μg/mL) [27]. Thus, the nucleotide sequence of the QRDR in the gene encoding the C subunit of DNA topoisomerase IV in A. laidlawii PG8R contained a sense mutation.

Figure 3.

Results of the alignments of the nucleotide (a) and amino acid (b) sequences of the parC gene of Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8 cells (1), cells of A. laidlawii PG8R (2), and the extracellular vesicles of A. laidlawii PG8R (3). Italics indicate the sequences of the forward and reverse primers. Nucleotide substitutions and amino acid replacements are enclosed in rectangles, the active site.

The development of resistance to quinolones in bacterial populations associated with point mutations in the QRDR of parC should lead to the rapid spread of the corresponding nucleotide sequences in bacterial communities. The main means of spreading antibiotic resistance genes in bacteria is horizontal transfer [30]. Recently, it was shown that the EVs of some bacteria may allow the traffic of genes that encode antibiotic-targeted proteins, thereby mediating the horizontal transfer of nucleotide sequences that determine antibiotic resistance in bacterial populations [31, 32].

Thus, to estimate the potential participation of the mycoplasma EVs in the traffic of the mutant gene that encoded the fluoroquinolone-targeted protein, the EVs of A. laidlawii PG8 and A. laidlawii PG8R were tested to determine the presence of the nucleotide sequences of parC QRDR. Previously [9, 14], we reported that the EVs of A. laidlawii PG8 contained the nucleotide sequences of several genes, which can be used as specific markers of the mycoplasma EVs, thereby allowing the detection of EVs and providing a control to detect the absence of bacterial cells in EV preparations. These data were considered when conducting this study.

PCR using primers that amplified the nucleotide sequences of marker genes in the EVs of A. laidlawii PG8 and parC QRDR from the mycoplasmas detected the parC QRDR-specific PCR signal, where DNA obtained from the EVs of A. laidlawii PG8 and A. laidlawii PG8R were used as templates (Figure 4). The sequencing data indicated that the PCR signals corresponded to parC QRDR from the mycoplasmas. The C → T transition at position 272 was also detected with A. laidlawii PG8R (Figure 3). Thus, this study demonstrated that A. laidlawii PG8 and A. laidlawii PG8R produced EVs that contained parC QRDR nucleotide sequences, which were copies of the gene sequences from the respective mycoplasma strains.

Figure 4.

Electrophoregrams of the amplification products of the nucleotide sequences of parC (1), ftsZ (2), and A23LR (3) of Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8, which were obtained by PCR using the total DNA (as a template) isolated from the cells (a) and extracellular vesicles (b) of A. laidlawii PG8R. M: molecular weight marker.

A. laidlawii PG8R EVs mediated the export of a parC QRDR sequence with a C → T transition at position 272, which produced a substitution in the amino acid sequence of the antibiotic-targeted protein. This suggests the possibility that EVs can spread the mutant gene in bacterial communities via horizontal transfer. This capacity was demonstrated recently in E. coli and P. aeruginosa model systems [33]. A study of similar processes in A. laidlawii model systems has yet to be made.

4. Conclusions

This study showed that the EVs secreted by A. laidlawii cells are involved with the development of the resistance to ciprofloxacin. The results also indicate that the mechanism of antibiotic resistance in this mycoplasma was associated with a mutation in a gene that encoded a quinolone-targeted protein, while the vesiculation level was also modulated. Furthermore, the EVs of A. laidlawii mediated the export of the nucleotide sequences of the gene that encoded the ciprofloxacin-targeted protein, as well as the antibiotic. These results demonstrate the necessity of applying appropriate approaches to the development of effective methods for controlling mycoplasma infections, as well as contamination of cell cultures and vaccines.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grant of the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (the 8048 Agreement), Russian Foundation for Basic Research 11-04-01406a, and 12-04-01052a, 12-04-31396, the Grant of President of Russian Federation (MK-3823.2023.4), and the Grant for state support of leading scientific schools of the Russian Federation (no. NSH-825.2012.4). The authors are grateful to G. F. Shaimardanova (PhD) for her help in the transmissive electron microscopy.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Folmsbee M, Howard G, Mcalister M. Nutritional effects of culture media on mycoplasma cell size and removal by filtration. Biologicals. 2010;38(2):214–217. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Windsor HM, Windsor GD, Noordergraaf JH. The growth and long term survival of Acholeplasma laidlawii in media products used in biopharmaceutical manufacturing. Biologicals. 2010;38(2):204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uphoff CC, Drexler HG. Detection of mycoplasma contaminations. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2013;946:1–13. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-128-8_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bébéar C, Pereyre S, Peuchant O. Mycoplasma pneumoniae susceptibility and resistance to antibiotics. Future Microbiology. 2011;6(4):423–431. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mariotti E, D’alessio F, Mirabelli P, di Noto R, Fortunato G, del Vecchio L. Mollicutes contamination: a new strategy for an effective rescue of cancer cell lines. Biologicals. 2012;40(1):88–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raherison S, Gonzalez P, Renaudin H, Charron A, Bébéar C, Bébéar CM. Evidence of active efflux in resistance to ciprofloxacin and to ethidium bromide by Mycoplasma hominis . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2002;46(3):672–679. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.672-679.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamaguchi Y, Takei M, Kishii R, Yasuda M, Deguchi T. Contribution of topoisomerase IV mutation to quinolone resistance in Mycoplasma genitalium . Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(4):1772–1776. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01956-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Couldwell DL, Tagg KA, Jeoffreys NJ, Gilbert GL. Failure of moxifloxacin treatment in Mycoplasma genitalium infections due to macrolide and fluoroquinolone resistance. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2013;24(10):822–828. doi: 10.1177/0956462413502008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chernov VM, Chernova OA, Mouzykantov AA, et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2011;11:1120–1130. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2011.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chernov VM, Chernova OA, Medvedeva ES, et al. Unadapted and adapted to starvation Acholeplasma laidlawii cells induce different responses of Oryza sativa, as determined by proteome analysis. Journal of Proteomics. 2011;74(12):2920–2936. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolás MF, Barcellos FG, Hess PN, Hungria M. ABC transporters in Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and Mycoplasma synoviae: insights into evolution and pathogenicity. Genetics and Molecular Biology. 2007;30(1):202–211. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Razin S, Hayflick L. Highlights of mycoplasma research-an historical perspective. Biologicals. 2010;38(2):183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scripal IG. Microorganisms—Agents of the Plant Diseases. Kiev, Ukraine: Naukova Dumka; 1989. (Edited by V. I. Bilay ). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chernov VM, Chernova OA, Mouzykantov AA, et al. Extracellular membrane vesicles and phytopathogenicity of Acholeplasma laidlawii PG8. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:6 pages. doi: 10.1100/2012/315474.315474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulp A, Kuehn MJ. Biological functions and biogenesis of secreted bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Annual Review of Microbiology. 2010;64:163–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schertzer JW, Whiteley M. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles in trafficking, communication and the host-pathogen interaction. Journal of Molecular Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2013;23:118–130. doi: 10.1159/000346770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ciofu O, Beveridge TJ, Kadurugamuwa J, Walther-Rasmussen J, Hoiby N. Chromosomal β-lactamase is packaged into membrane vesicles and secreted from Pseudomonas aeruginosa . Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2000;45(1):9–13. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Lee EY, Kim SH, et al. Staphylococcus aureus extracellular vesicles carry biologically active β-lactamase. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013;57:2589–2595. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00522-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole RM. Methods in Mycoplasmology. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1983. (Edited by S. H. Razin, J. G. Tully ). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chapman JS, Georgopapadakou NH. Fluorometric assay for fleroxacin uptake by bacterial cells. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1989;33(1):27–29. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Y, Dai M, Hao H, et al. The role of RamA on the development of ciprofloxacin resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023471.e23471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CLSI Approved Standard. M100-S15. Wayne, Pa, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2005. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolling GL, Matthews KR. Export of virulence genes and Shiga toxin by membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1999;65(5):1843–1848. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.5.1843-1848.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maniatis T, Fritsch EE, Sabrook J. Molecular Cloning. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maredia R, Devineni N, Lentz P, et al. Vesiculation from Pseudomonas aeruginosa under SOS. The Scientific World Journal. 2012;2012:8 pages. doi: 10.1100/2012/402919.402919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kadurugamuwa JL, Beveridge TJ. Bacteriolytic effect of membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on other bacteria including pathogens: conceptually new antibiotics. Journal of Bacteriology. 1996;178(10):2767–2774. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2767-2774.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taganov KD, Gushchin AE, Abramycheva NI, Govorun VM. Role of mutations in the a-subunit of Acholeplasma laidlawii PG-8B topoisomerase IV in formation of resistance to fluoroquinolones. Molekuliarnaia Genetika, Mikrobiologiia I Virusologiia. 2000;(2):30–33. (Rus). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruiz J. Mechanisms of resistance to quinolones: target alterations, decreased accumulation and DNA gyrase protection. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 2003;51(5):1109–1117. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bébéar C, Renaudin H, Charron A, Bové JM, Bébéar C, Renaudin J. Alterations in topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase in quinolone-resistant mutants of Mycoplasma hominis obtained in vitro. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1998;42(9):2304–2311. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.9.2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ip M, Chau SSL, Chi F, Tang J, Chan PK. Fluoroquinolone resistance in atypical pneumococci and oral streptococci: evidence of horizontal gene transfer of fluoroquinolone resistance determinants from Streptococcus pneumoniae . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2007;51(8):2690–2700. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00258-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaron S, Kolling GL, Simon L, Matthews KR. Vesicle-mediated transfer of virulence genes from Escherichia coli O157:H7 to other enteric bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2000;66(10):4414–4420. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.10.4414-4420.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rumbo C, Fernández-Moreira E, Merino M, et al. Horizontal transfer of the OXA-24 carbapenemase gene via outer membrane vesicles: a new mechanism of dissemination of carbapenem resistance genes in Acinetobacter baumannii . Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2011;55(7):3084–3090. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00929-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manning AJ, Kuehn MJ. Contribution of bacterial outer membrane vesicles to innate bacterial defense. BMC Microbiology. 2011;11, article 258 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]