Abstract

A species of Streptomyces, Streptomyces ginsengisoli, a river isolate, was evaluated for production of an enzyme, L-asparaginase, with multiple functions mainly anticancer activity. The actinomycete was subjected to submerged fermentation by “shake flask” method. The quantity of L-asparaginase produced was estimated as 3.23 μmol/mL/min. The effect of various culture conditions on L-asparaginase production was studied by adopting a method of variation in one factor at a time. Of the various conditions tested, glucose (followed by starch) and peptone served as good carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively, for maximal production of enzyme at pH 8. The temperature of 30°C and an incubation period of 5 days with 0.05 g% asparagine concentration were found to be optimum for L-asparaginase production.

1. Introduction

L-asparaginase (L-asparagine amido hydrolase E.C.3.5.1.1) enzyme which converts L-asparagine to L-aspartic acid and ammonia has been used as a chemotherapeutic agent in the treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia for over 30 years [1]. The clinical action of this enzyme is attributed to the reduction of L-asparagine, since tumor cells unable to synthesize this enzyme are selectively killed by L-asparagine deprivation [1–3].

Due to its prompt therapeutic potential, screening of microbial sources for asparaginase activity has been greatly intensified and well documented in filamentous fungi, yeast and bacteria like E. coli [4, 5], Vibrio succinogenes [6], Erwinia carotovora [7, 8], and Bacillus sp. [9, 10]. Among the fungi Mucor sp. [11], Penicillium sp. [12, 13], and yeast-like Candida utilis [14] have been proved to be potential producers of this enzyme.

Unfortunately the rapid development of side effects has limited the usage of currently available L-asparaginase. PEG-asparaginase, a form of Escherichia coli L-asparaginase covalently linked to polyethylene glycol, was rationally synthesized to decrease immunogenicity of the enzyme and prolong its half-life [1].

Actinomycetes are recognized as comparatively less explored source for L-asparaginase and therefore act as candidates for the production of L-asparaginase [15, 16]. Actinomycetes like S. griseoluteus [17], S. karnatakensis [18], S. venezuelae [19], S. gulbargensis [3], and Nocardia levis were reported to be potential candidates.

The present investigation deals with isolation and characterization of L-asparaginase from river sediment isolates of actinomycetes as a novel source of enzyme which is effective against leukemia. The isolate was identified as Streptomyces ginsengisoli by 16S r-DNA sequencing studies. Further analysis deals with optimization of different parameters for L asparaginase production.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Isolation and Screening of Actinomycetes for Production of L-Asparginase by Plate Assay

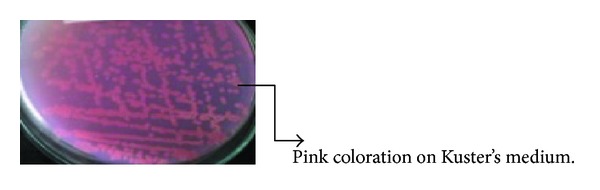

The actinomycetes were isolated from river sediment samples collected from various locations in India. Seven isolates were screened for L-asparaginase production by plate assay [20]. The medium used for screening was Kuster's medium. The principle on which this screening was based is as follows: The medium contained phenol red indicator which turns pink in colour under alkaline conditions. The enzyme L-asparaginase will act on the substrate L-asparagine leading to production of ammonia which shifts the pH towards alkaline. The pink zone around the colony indicates that the organism is able to produce L-asparaginase. Thus this qualitative method was used as a screening test for L-asparaginase production.

2.2. Identification of Selected Isolate Was Carried out by 16s r-RNA Sequencing Followed by BLAST Analysis

2.2.1. Cultivation of Actinomycetes

In order to obtain sufficient growth and maximum enzyme production from the identified strain, different media selected from the literature, that are used for cultivation of Actinomycetes were used [21–24] and the one giving maximum enzyme activity was used for further analysis.

2.3. Determination of Production Profile of L-Asparaginase

For determining the production profile of L-asparaginase, actinomycete colonies from the plate were directly inoculated into asparagine dextrose salt broth (ADS) containing 1% dextrose, 0.05% L-aspargine, 0.05% di potassium hydrogen phosphate, and 0.2% meat extract with initial pH 7. The inoculated flasks were then incubated at 30°C for 7 days in order to estimate the cell growth of the strain as well as L-asparaginase production for every 24 h interval. Cell growth was expressed in terms of dry weight of biomass (mg/mL) [18].

L-asparaginase activity was measured by following method [23, 25]. The cultures in ADS broth were centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 30 mins and the resultant supernatant, that is, the crude extract, was used to determine the L-asparaginase activity. Reaction was started by adding 0.5 mL of crude cell free extract into 0.5 mL of 0.04 M L-asparagine solution and 0.5 mL of 0.05 M Tris HCL buffer pH 8 and incubated at 37°C for 30 mins in water bath. The reaction was stopped by addition of 0.5 mL of 1.5 M TCA (trichloroacetic acid). Precipitated proteins were removed by centrifugation at 8000 rpm for 15 mins at 4°C, and the ammonia released was determined spectrometrically at 425 nm by nesslerization (by Nessler's method). Tubes kept at zero time incubation served as control. Enzyme activity was determined on the basis of liberation of ammonia calculated with reference to a standard curve of ammonium sulphate. In the concentration range of 0.1 mL of supernatant was added to 3.75 mL of distilled water, followed by addition of 0.2 mL of Nessler's reagent and was incubated at room temperature for 10 mins after which the absorbance was taken at 425 nm.

Enzyme Unit.One unit of asparaginase is the amount of enzyme which catalyzed the formation of 1 umol of ammonia per minute at 37°C [23].

The cell dry weight was recorded simultaneously at the interval of 24 hrs by drying the cell debris collected after centrifugation in an oven at 90°C for 24 h.

2.4. Effect of Sonication

100 mL of ADS broth was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 20 minutes followed by separation of cell pellets, to which 0.05 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.8) (5 mL) was added. Sonication was carried out with 30 pulses for 6 minutes at 4°C. The lysed cell pellet was then centrifuged at 47,000 g for 12 min and enzyme activity of the cell-free supernatant after sonication and that of a cell pellet after sonication were determined [26].

2.5. Optimization of L-Asparaginase Production (One Factor at a Time)

2.5.1. Initial pH and Temperature Optimization

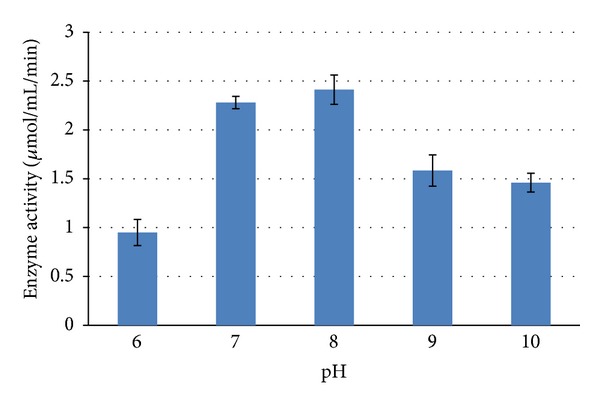

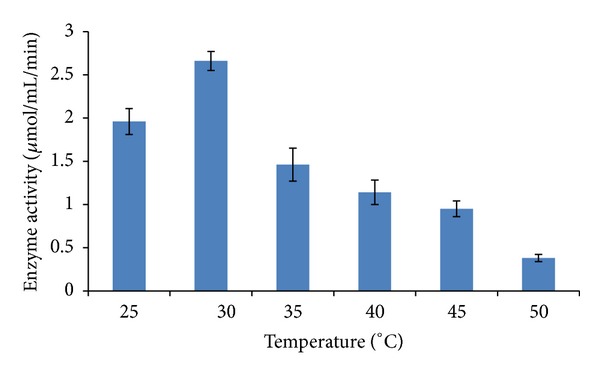

Impact of pH on the production of L-asparaginase was examined by culturing the strain in ADS broth adjusted to various pH levels ranging from 4.0 to 10.0. The optimal pH achieved at this step was used for further study. To determine the optimum temperature for L-asparaginase production, the strain was cultured in ADS broth at different temperatures ranging from 25 to 50°C for an incubation period of 5 days [2].

2.5.2. Carbon Source

To investigate the effect of carbon sources on L-asparaginase production by the strain, ADS broth was supplemented with different carbon sources such as starch, mannitol, lactose, sucrose, and glucose each at a concentration of 1% (w/v) [3, 27] keeping other components constant.

2.5.3. Nitrogen Source

Different nitrogen sources, namely, beef extract, yeast extract, and peptone, were added at a concentration of 0.2% (w/v) to ADS broth keeping other ingredients constant except meat extract [3]. Inorganic nitrogen source was not tried as it would interfere in enzyme assay.

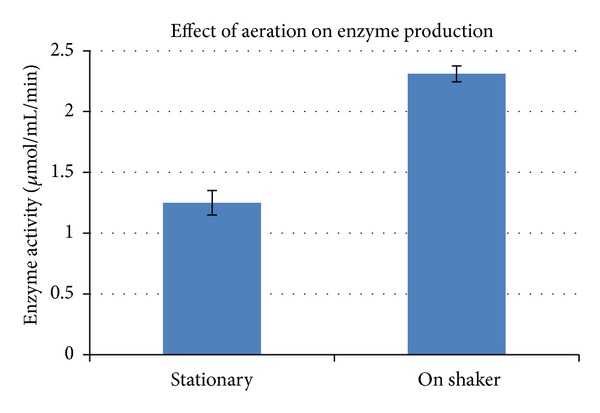

2.5.4. Effect of Aeration

To study the effect of aeration, two sets of flasks were incubated; one flask was incubated under stationary conditions and another was kept on shaker at 120 rpm for 5 days using ADS broth.

All the experiments were performed in triplicates and results were expressed as an average value with standard deviation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Enrichment, Isolation, and Screening for L-Asparaginase Production by Plate Assay

Isolates obtained were screened for the production of the enzyme L-asparaginase by using plate assay method (qualitative method). Results obtained showed higher intensity of pink coloration for three out of seven cultures tested (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The results of plate assay method for qualitative determination of enzyme production by the isolate.

Cultures giving positive test with plate assay method were then checked for enzyme activity quantitatively. Results obtained showed that one of the three tested cultures gave higher enzyme activity and therefore it was selected for further optimization studies on L-asparaginase production.

3.2. Identification of the Selected Strain of Actinomycetes

Identification of the selected strain was carried out by 16s r-RNA sequencing and the isolate was identified as Streptomyces ginsengisoli. (GenBank Accession number KF649337).

3.3. Use of Different Media for Growth and Production of Enzyme

Comparative analysis was carried out by inoculating the culture in different media in order to obtain increased growth and production of the enzyme. Results revealed that higher enzyme activity was observed in ADS broth as compared to other media used (Table 1). ADS broth was selected for all further experiments.

Table 1.

L-asparaginase enzyme activity by Streptomyces ginsengisoli on different media.

| Name of the medium | Enzyme activity (μmoles/mL/min) |

|---|---|

| Bennett's broth | 1.04 ± 0.04 |

| Yeast extract malt extract | 0.92 ± 0.06 |

| Asparagine dextrose salt broth (ADS) | 2.53 ± 0.12 |

| Bennett's broth + 0.05 L-asparagine | 1.268 ± 0.07 |

| Bennett's broth + 0.05 L-asparagine (casein hydrolysate replaced) | 1.712 ± 0.09 |

| Bennett's broth + 0.2 L-asparagine (casein hydrolysate replaced) | 1.206 ± 0.25 |

Values are the mean of three replicates ± SD.

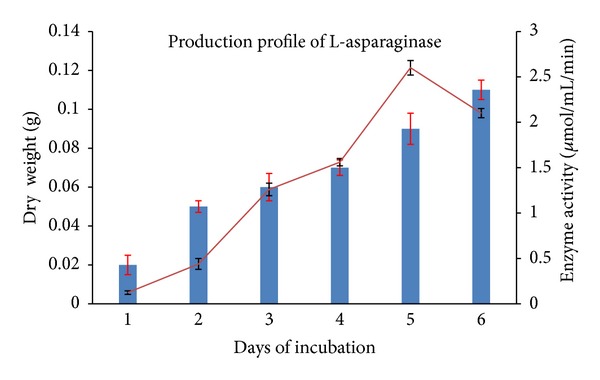

3.4. Production Profile of L-Asparaginase

Production of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces ginsengisoli started after 24–32 h of cell growth. Good correlation between cell growth and enzyme activity was observed when daywise analysis of dry weight and enzyme activity was carried out. Maximum activity was observed on the fifth day of incubation from the day of inoculation of the culture (Figure 2). A positive correlation between enzyme activity and cell mass over a time period of 24–120 hours has also been reported by Priya et al., in their work on Streptomyces sp. (TA22) isolated from Western Ghats, lndia [24].

Figure 2.

Production profile of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces ginsengisoli grown in asparagine dextrose salt Broth. A positive correlation between cell dry weight (bar chart) and enzyme activity (line) was observed.

There are few reports on actinomycetes producing predominantly extracellular L-asparaginase, while majority of bacterial species and few actinomycetes like Streptomyces. karnatakensis [18], and Streptomyces albidoflavus [27] are reported to be cell bound [1]. Comparison of extracellular and intracellular enzyme activity of Streptomyces ginsengisoli revealed that enzyme produced by the culture is predominantly extracellular. (Table 2).

Table 2.

66% of the enzyme activity was found to be extracellular when compared with intracellular enzyme activity.

| Streptomyces ginsengisoli | Enzyme activity (μmol/mL/min) |

Enzyme activity (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular | Cell-free supernatant (before sonication) | 2.412 ± 0.19 | 66 |

| Intracellular | Supernatant (after sonication) | 0.888 ± 0.03 | 25 |

| Precipitate (after sonication) | 0.316 ± 0.12 | 9 |

For optimization of enzyme production, extracellular enzyme activity was considered.

3.5. Optimization of L-Asparaginase Production

3.5.1. Initial pH and Temperature Optimization

A study of initial pH levels (6–10) of ADS broth on production of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces ginsengisoli indicated an optimal enzyme activity at pH 8.0 (Figure 3). Optimum pH for production of L-Asparaginase by Streptomyces albidoflavus has been reported to be with the range of 7.5–8 which was found to be in accordance with our work [27].

Figure 3.

Effect of initial pH levels of the medium on production of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces ginsengisoli.

Impact of temperature on L-asparaginase production was studied over a temperature range of 25°C to 50°C where maximum enzyme production was observed at 30°C (Figure 4). Actinomycetes like Streptomyces albidoflavus have been reported to produce L-asparaginase within the temperature range of 30–35 [6]. The present study revealed that L-asparaginase production was high when the culture was grown in ADS broth with an initial pH 8.0 and 30°C incubation.

Figure 4.

Effect of different levels of incubation temperature on production of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces ginsengisoli. Values are the means of three replicates ± SD.

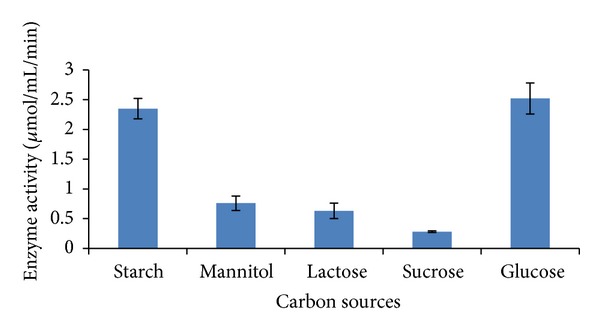

3.5.2. Carbon Sources

Different carbon sources like starch, mannitol, lactose, sucrose, and glucose were amended in asparagine dextrose salt broth to determine their impact on L-asparaginase production (Table 3) (Figure 5). As compared to other carbon sources tested, L-asparaginase production was high in presence of glucose. Comparable results were also obtained when starch was used as a carbon source. Maximum L-asparaginase production has been reported by Amycolatopsis CMU-H002 when ADS broth was amended with starch as the carbon source [23]. Biosynthesis of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces albidoflavus has been reported to be higher when the basal medium was supplemented with starch [27]. Sucrose, when added to the basal medium, served as a good carbon source for L-asparaginase production by actinomycetes isolated from estuarine fishes [25].

Table 3.

L-asparaginase production by Streptomyces ginsengisoli grown in asparagine dextrose salt broth amended with different carbon sources.

| Carbon source | Enzyme activity (μmol/mL/min) |

|---|---|

| Starch | 2.348 ± 0.17 |

| Mannitol | 0.76 ± 0.12 |

| Lactose | 0.632 ± 0.13 |

| Sucrose | 0.28 ± 0.015 |

| Glucose | 2.52 ± 0.26 |

Values are the means of three replicates ± SD.

Figure 5.

L-asparaginase production by Streptomyces ginsengisoli grown in asparagine dextrose salt broth amended with different carbon sources.

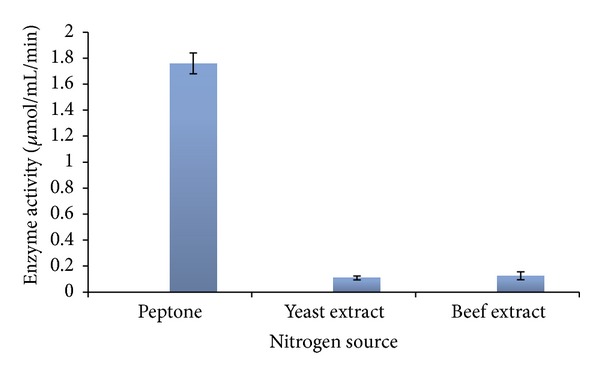

3.5.3. Nitrogen Sources

Effect of nitrogen compounds on production of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces ginsengisoli was studied by incorporating different nitrogen sources to ADS Broth containing 1% glucose. L-asparaginase production varied with the three nitrogen sources tested. Among them culture medium amended with peptone favored maximum enzyme production by this strain (Table 4) (Figure 6). For production of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces albidoflavus, yeast extract has been reported as a good nitrogen source [27]. Similar results have been reported by Khamna et al. in their studies associated with production of L-asparaginase from isolates obtained from rhizosphere soil of Thai medicinal plant [23].

Table 4.

L-asparaginase production by Streptomyces ginsengisoli grown in asparagine dextrose salt broth amended with different nitrogen sources.

| Nitrogen source | Enzyme activity (μmol/mL/min) |

|---|---|

| Peptone | 1.76 ± 0.13 |

| Beef extract | 0.126 ± 0.15 |

| Yeast extract | 0.1904 ± 0.015 |

Values are the means of three replicates ± SD.

Figure 6.

L-asparaginase production by Streptomyces ginsengisoli grown in asparagine dextrose salt broth amended with different nitrogen sources.

3.5.4. Effect of Aeration

Considerable decrease in enzyme activity was observed when culture was allowed to grow under stationary conditions as compared to the one kept on shaker at 120 rpm (Figure 7). Enzyme activity of the optimized media was found to be 28% more than the unoptimized media (Table 5). A correlation between agitation speed and enzyme production has still been reported by Jain et al. in their work on Streptomyces gulbargensis [16].

Figure 7.

Effect of agitation on L-asparaginase production by Streptomyces ginsengisoli. Values are the means of three replicates ± SD.

Table 5.

Comparison of enzyme activity obtained before and after optimization where 28% higher activity was obtained for optimized asparagine dextrose salt broth.

| Before optimization | After optimization | |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme activity (μmol/mL/min) |

2.52 | 3.23 |

The present study revealed that all the selected parameters examined showed a considerable impact on L-asparaginase production by the novel isolate Streptomyces ginsengisoli. High activity of the enzyme was obtained at pH 8 and temperature 30°C. Maximum enzyme production was achieved when asparagine dextrose salt broth was supplemented with glucose and peptone as carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively. Optimization of growth parameters showed significant effect on production of enzyme L-asparaginase from 2.52 to 3.23 μmol/mL/min. Thus, use of optimized asparagine dextrose salt broth increased enzyme activity by 28%. To the best of our knowledge this is the first report on production of L-asparaginase enzyme by Streptomyces ginsengisoli. The present work was aimed at evaluation of the parameters for its production and not at isolation and characterization of the enzyme. Moreover the work does not include investigation of the anticancer effect of L- Asparaginase.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Savitri S, Asthana N, Azmi W. Microbial L-asparaginase: a potent antitumour enzyme. Indian Journal of Biotechnology. 2003;2(2):184–194. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poorani E, Saseetharan MK, Dhevagi P. L-asparaginase production and molecular identification of marine Streptomyces sp strain EPD 27. International Journal of Integrative Biology. 2009;7(3):150–155. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amena S, Vishalakshi N, Prabhakar M, Dayanand A, Lingappa K. Production, purification and characterization of L-asparaginase from Streptomyces gulbargensis . Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 2010;41(1):173–178. doi: 10.1590/S1517-838220100001000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrulis IL, Barrett MT. DNA methylation patterns associated with asparagine synthetase expression in asparagine-overproducing and -auxotrophic cells. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1989;9(7):2922–2927. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.7.2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verma N, Kumar K, Kaur G, Anand S. L-asparaginase: a promising chemotherapeutic agent. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology. 2007;27(1):45–62. doi: 10.1080/07388550601173926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Distasio JA, Salazar AM, Nadji M, Durden DL. Glutaminase-free asparaginase from Vibrio succinogenes: an antilymphoma enzyme lacking hepatotoxicity. International Journal of Cancer. 1982;30(3):343–347. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910300314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maladkar NK, Singh VK, Naik SR. Fermentative production and isolation of L-asparginase from Erwinia caratovora EC-113. Bioscience Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 1995;59(4):749–750. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deokar VD, Vetal MD, Lambert R. Production of intracellular L-asparginase from Erwinia caratovora and its statistical optimization using response surface methodology. International Journal of Chemical Sciences and Application. 2010;1(1):25–26. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph B, Rajan SS. L-lysine alpha oxidase from fungi as an anti tumor enzyme agent. Advanced Biotechnology. 2011;10(8):27–30. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher SH, Wray LV., Jr. Bacillus subtilis 168 contains two differentially regulated genes encoding L-asparaginase. Journal of Bacteriology. 2002;184(8):2148–2154. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.8.2148-2154.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohapatra BR, Sani RK, Banerjee UC. Characterization of L-asparaginase from Bacillus sp. isolated from an intertidal marine alga (Sargassum sp.) Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1995;21(6):380–383. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patro KR, Gupta N. Extraction, purification and characterization of L-asparginase from Penicillium sp. by submerged fermentation. International Journal of Biotechnology and Molecular Biology Research. 2012;3(3):30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soniyambi AR, Lalitha S, Pravesh BV, Priyadarshini V. Isolation, production and anti tumor activity of L-asparginase of Penicillium sp . International Journal of Microbiological Research. 2011;2(1):38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kil JO, Kim GN, Park I. Extraction of extracellular L-asparaginase from Candida utilis . Bioscience, biotechnology, and biochemistry. 1995;59(4):749–750. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhevagi P, Poorani E. Isolation and characterization of L-asparaginase from marine actinomycetes. Indian Journal of Biotechnology. 2006;5(4):514–520. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain R, Zaidi KU, Verma Y, Saxena P. L-Asparginase: a promosing enzyme for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. People's Journal of Scientific Research. 2012;5(1):29–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumar KPV, Girija SG, Prabhakar T. Optimization of L-asparginase production by Streptomyces griseoluteus WS3/1 using experimental methods. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences. 2011;10(10):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mostafa SA. Activity of L-Asparaginase in cells of Streptomyces karnatakensis . Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde, Infektionskrankheiten und Hygiene: Zweite Naturwissenschaftliche. 1979;134(4):343–351. doi: 10.1016/s0323-6056(79)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mostafa SA. Production of L-asparaginase by Streptomyces karnatakensis and Streptomyces venezuelae . Zentralblatt für Bakteriologie, Parasitenkunde, Infektionskrankheiten und Hygiene: Zweite Naturwissenschaftliche. 1979;134(5):429–436. doi: 10.1016/s0323-6056(79)80096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gulati R, Saxena RK, Gupta R. A rapid plate assay for screening L-asparaginase producing micro-organisms. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 1997;24(1):23–26. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albanese E, Kafkewitz K. Effect of medium composition on the growth and asparaginase production of Vibrio succinogenes . Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1978;36(1):25–30. doi: 10.1128/aem.36.1.25-30.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Porter JN, Wilhem JJ, Tresner HD. Method for the preferential isolation of Actinomycetes from soils. Applied Microbiology. 1960;8(3 ):174–178. doi: 10.1128/am.8.3.174-178.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khamna S, Yokota A, Lumyong S. L-Asparaginase production by actinomycetes isolated from some Thai medicinal plant rhizosphere soils. International Journal of Integrative Biology. 2009;6(1):22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Priya PM, Radhakrishnan M, Balagurunathan R. Production and optimization of L-asparaginase from Streptomyces sp (TA22) isolated from Western Ghats, India. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research. 2011;3(4):618–624. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sahu MK, Sivakumar K, Poorani E, Thangaradjou T, Kannan L. Studies on L-asparaginase enzyme of actinomycetes isolated from estuarine fishes. Journal of Environmental Biology. 2007;28(2):465–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saptarshi SD, Lele SS. Application of evolutionary optimization technique in maximizing the recovery of L-asparginase from E. caratovora MTCC, 1428. Global Journal of Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2010;5(2):97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Narayana KJP, Kumar KG, Vijayalakshmi M. L-asparaginase production by Streptomyces albidoflavus . Indian Journal of Microbiology. 2008;48(3):331–336. doi: 10.1007/s12088-008-0018-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]