Abstract

The goal of this study was to determine which cocaine dependent patients engaged in an intensive outpatient program (IOP) were most likely to benefit from extended continuing care (24 months). Participants (N=321) were randomized to: IOP treatment as usual (TAU), TAU plus Telephone Monitoring and Counseling (TMC), or TAU plus TMC plus incentives for session attendance (TMC+). Potential moderators examined were gender, stay in a controlled environment prior to IOP, number of prior drug treatments, and seven measures of progress toward IOP goals. Outcomes were: (1) abstinence from all drugs and heavy alcohol use, and (2) cocaine urine toxicology. Follow-ups were conducted at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months post baseline. Results indicated there were significant effects favoring TMC+ over TAU on the cocaine urine toxicology outcome for participants in a controlled environment prior to IOP and for those with no days of depression early in IOP. Trends were obtained favoring TMC over TAU for those in a controlled environment (cocaine urine toxicology outcome) or with high family/social problem severity (abstinence composite outcome), and TMC+ over TAU for those with high family/social problem severity or high self-efficacy (cocaine urine toxicology outcome). None of the other potential moderator effects examined reached the level of a trend. These results generally do not suggest that patients with greater problem severity or poorer performance early in treatment on the measures considered in this report will benefit to a greater degree from extended continuing care.

Keywords: cocaine dependence, continuing care, adaptive treatment, incentives, moderators

1. Introduction

Continuing care interventions that extend initial, acute episodes of care are often recommended for individuals receiving treatment for substance use disorders. The provision of continuing care is seen as important because substance use disorders are often chronic, at least in some individuals (Dennis & Scott, 2007; Hser, Longshore, & Anglin, 2007; McLellan, Lewis, O'Brien, & Kleber, 2000). Controlled studies have provided evidence of the effectiveness of continuing care, particularly with interventions that feature longer durations and active efforts to deliver care (McKay, 2009b; McKay et al., 2010; Scott & Dennis, 2009).

It does not appear, however, that all patients with substance use disorders benefit to the same degree from continuing care interventions. In a study of Recovery Management Checkups, which provided monitoring and linkage back to treatment over four years, the intervention was more effective for participants with earlier onset of substance use disorders and higher scores on a measure of criminal and violent behavior (Dennis & Scott, 2012). Positive effects on drinking outcomes in a study of a behavioral marital therapy continuing care intervention persisted for an additional 12 months in alcoholics with more severe drinking and marital problems at the start of treatment (O'Farrell, Choquette, & Cutter, 1998).

In our own work, patients' initial response to treatment has been a good indicator of continuing care needs. Patients who continued to use cocaine during a 4-week intensive outpatient program (IOP) had worse outcomes over 24 months than those who were cocaine abstinent during IOP, but benefited to a greater degree from individualized relapse prevention relative to standard group continuing care (McKay et al., 1999). In a second study, patients who made poor progress toward achieving the primary goals of a 4-week IOP had worse substance use outcomes over 24 months than those who achieved IOP goals, but benefited to a greater degree from more intensive clinic-based continuing care relative to a less intensive telephone intervention. Conversely, those who achieved IOP goals did better in the telephone condition (McKay et al., 2005). In a third study, patients who were less committed to change or had less social support for recovery by the fourth week of IOP benefited from extended telephone-based continuing care relative to IOP only, whereas patients who had made more progress in these areas did not. Women and those with prior treatment experiences also benefited from telephone continuing care, whereas men and those with no prior treatments did not (McKay et al., 2011).

We recently conducted a study that evaluated the effectiveness of two extended continuing care interventions that combined telephone and clinic-based sessions provided over 24 months. The participants were patients enrolled in publicly-funded IOPs; all were cocaine dependent and the majority were also alcohol dependent. One of the two continuing care interventions provided incentives for each session completed in the first year, whereas the other did not. Findings from this study indicated that there were no significant main effects for any of the continuing care group comparisons. However, patients who used any cocaine or alcohol in the week prior to IOP or during the first three weeks of IOP had significantly better substance use outcomes over 24 months if they were randomized to extended continuing care (McKay et al., 2013). Conversely, there were no treatment effects in patients who were cocaine and alcohol abstinent during this period. Incentivizing continuing care attendance increased the number of sessions received, but did not further improve outcomes (McKay et al., in press; Van Horn et al., 2011).

The goal of the this article was to determine if the factors found to predict response to telephone continuing care in our prior study (McKay et al., 2011)—gender, readiness to change, social support for recovery, and prior treatments for substance use disorders—would also moderate outcomes in the cocaine study described above (McKay et al., in press). In addition, other measures of progress toward IOP goals— commitment to abstinence, self-efficacy, days with depression, overall psychiatric severity, and family/social problem severity—were also examined to determine if scores on these measures moderated response to continuing care. Finally, the potential moderating effects of whether the patient had been in a controlled environment immediately prior to IOP were also considered.

Specifically, we hypothesized that larger treatment effects favoring extended continuing care would be found in women, and in participants who had more prior drug treatments or had been in a controlled environment prior to IOP, as these factors were indicators of greater addiction severity. Participants who had made poorer progress toward the goals of IOP, as indicated by lower readiness to change, poorer social support for recovery, lack of a commitment to abstinence, low self-efficacy, more days of depression, and higher psychiatric symptoms severity at the end of IOP, were also expected to derive greater benefit from extended continuing care.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The participants were 321 adults enrolled in two publicly funded IOPs in Philadelphia who met criteria for lifetime DSM-IV cocaine dependence (SCID; First et al., 1996) and had used cocaine in the 6 months prior to entering treatment. The other criteria for eligibility were a willingness to participate in research and be randomly assigned to a treatment condition; completion of two weeks of IOP; no psychiatric or medical condition that precluded outpatient treatment (i.e., severe dementia, current hallucinations); between the ages of 18 and 65; and no regular IV heroin use within the past 12 months. Additional inclusion criteria are described elsewhere (McKay et al., in press).

The participants were on average 43.2 (sd= 7.4) years old and had 11.6 (sd= 1.8) years of education. The majority of participants were male (76%) and African American (89%). The participants used cocaine on an average of 42.2% (sd=30.7) of the days in the six months prior to baseline, and drank alcohol on 32.0% (sd= 32.8) of the days. They averaged 4.5 (sd= 5.6) prior treatments for drug problems.

2.2. Intensive Outpatient Treatment

The IOP programs provided approximately 9 hours of group-based treatment per week, and patients could typically attend for up to 3–4 months (McKay et al., 2010). Patients who completed the IOP at these programs were typically offered 2 months of standard outpatient treatment (i.e., one group counseling session per week) for a total of up to 6 months of treatment.

2.3. Continuing Care Treatment Conditions

2.3.1. Telephone monitoring and counseling (TMC)

Participants had a face-to-face session to orient them to the protocol, and then received brief telephone calls for up to 24 months. These 20 minute calls were offered weekly for the first 8 weeks, every other week for the next 44 weeks, once per month for 6 months, and every other month for the final 6 months. Each call began with a structured 13-item assessment of current substance use, HIV risk behaviors, IOP attendance, risk factors for relapse, and protective factors, which was referred to as the progress assessment. CBT-based counseling was linked to the results of the progress assessment and also addressed any anticipated risky situations. Potential coping strategies and behaviors were identified and briefly rehearsed during the remainder of the session. Participants could complete some of sessions in person, rather than over the telephone, if they had difficulty in getting private access to a telephone or preferred to attend the session at the clinic. The intervention is fully described elsewhere (McKay et al., in press; 2010).

2.3.2. Telephone monitoring and counseling plus incentives (TMC+)

This intervention was the same as TMC, with the addition of incentives for attending sessions. Participants received a $10 gift coupon for each regularly scheduled or step care session attended in the first year, and bonus $10 gift coupons every time 3 consecutively scheduled sessions were completed. The coupons were for department stores and a local grocery store chain.

2.3.3. Therapists

Seven therapists delivered both TMC and TMC+. All therapists had prior experience with providing outpatient treatment for substance use disorders, and four had provided telephone-based continuing care in a prior study (McKay et al., 2010). Five of the therapists had MA-level degrees in psychology or social work, one had a BA, and one had a Ph.D. in clinical psychology.

2.3.4. Adherence to treatment protocols

The TMC and TMC+ sessions were audiotaped to facilitate supervision and monitor adherence to the protocol as described in the manuals. Individual supervision was provided weekly by the study clinical coordinator, and one group supervision session was also held per week. Any deviations from the treatment protocol identified by the clinical coordinator were immediately addressed in the weekly supervision meetings. Ratings of audio recordings of the sessions indicated high adherence to the manual in both TMC and TMC+ (see McKay et al., in press).

2.4. Procedures

2.4.1. Recruitment

Potential participants were screened during their first two weeks in the two IOPs by the study research technicians. Those who appeared eligible and were interested in participating were informed that they would be given a full screening if they completed two weeks of the IOP. Informed consent procedures were completed for those who appeared eligible after completing 2 weeks of IOP. The study was conducted in compliance with the policies of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania. Participants were recruited between July 2007 and November 2009.

2.4.2. Representativeness of the study sample

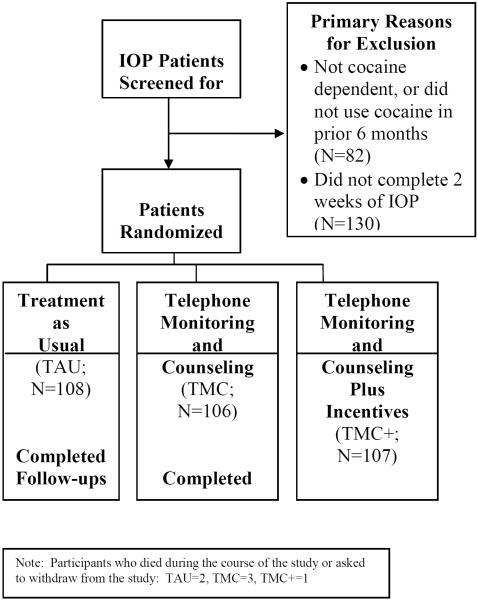

A total of 773 patients were screened at the two IOPs, and of these, 321 were eligible and willing to participate and were enrolled in the study (see Figure 1). The primary reasons for failure to enter the study were as follows: did not have lifetime cocaine dependence or had no cocaine use in the prior 6 months (82 of 452 not eligible, or 18%), stopped coming to IOP during the first two weeks of treatment (130, or 29%), had no contacts (67, or 15%), and had regular IV opiate use in the prior 12 months (61, or 13%).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram

2.4.3. Randomization procedures

Separate randomized allocation schemes were used at each site. Blocked randomization schemes, using blocks of size 30, were used to yield a balanced allocation of participants to the three treatment conditions at each site.

2.4.4. Assessments

Baseline assessments were completed in week 3 of IOP. Follow-up assessments were conducted at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months post baseline. Participants received $50 for the baseline assessment, and $50 each for the six follow-up sessions. All study interviews were conducted by research personnel who were blind to the study hypotheses, but not to treatment condition. The nature of material gathered at follow-ups, informal comments made by participants, and the length of the follow-up precluded maintaining a cadre of interviewers unaware of treatment condition assignment.

2.5. Moderator Measures

2.5.1. Demographic treatment variables

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan, Luborsky, Woody, & O'Brien, 1980; McLellan et al., 1985) was used to gather demographic data, and information on prior treatments for substance use disorders and problem severity levels during IOP, and drug use at each follow-up. ASI variables included in the moderator analyses that assessed pre-treatment factors were gender, number of treatments for substance use disorders (0–2 vs. 3 or more), and whether in a controlled environment immediately prior to IOP.

2.5.2. Cognitive and motivational variables

Readiness to change was assessed with the University of Rhode Island Change Assessment Questionnaire (URICA; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1984). A total score was calculated as the sum of the contemplation, action, and maintenance scores divided by the pre-contemplation score. Degree of commitment to abstinence was assessed with the Thoughts About Abstinence Scale (Hall et al. 1991), a single-item measure with 6 response options that delineate different abstinence goals. As in the Hall et al. (1991) study, the measure was dichotomized (absolute abstinence vs. less stringent goals). The Drug-Taking Confidence Questionnaire (DTCQ; Annis & Martin 1985) was used to assess self-efficacy in 8 domains. Scores on the 8 subscales were averaged to produce one predictor variable.

2.5.3. Psychiatric variables

Two ASI variables assessed psychiatric symptom severity: the psychiatric composite score and days of depression in the prior 30 days

2.5.4. Family-social variables

Social support for substance use was assessed with the Important People and Activities (IPA) interview (Zywiak et al., 2009). Participants nominate up to 10 people in their social network, and indicate how many support or encourage continued substance use. Participants were categorized into two groups: 0 vs. 1 or more people who support continued use. Family-social problem severity in the prior 30 days was assessed with the ASI composite score, with higher scores indicating greater problem severity. Therefore, higher scores on each of these two measures were indicative of greater family/social problems (i.e., poorer social support).

2.6. Substance Use Measures

2.6.1. Self-reported cocaine and alcohol use

Time-line follow-back (TLFB) (Sobell, Maisto, Sobell, & Cooper, 1979) calendar assessment techniques were used to gather self-reports of cocaine and alcohol use during the 6 months preceding the baseline assessment and the 24 month follow-up period. In validity studies with drug abusers, TLFB reports of days of cocaine use were highly correlated with urine toxicology results (Ehrman & Robbins, 1994; Fals-Stewart et al., 2000). In alcoholic samples, TLFB reports of percent days abstinent have generally correlated .80 or better with collateral reports (Maisto, Sobell, & Sobell, 1979; Stout, Beattie, Longabaugh, & Noel, 1989). In cases where participants missed one or more follow-ups but then completed a subsequent follow-up, data from the missing follow-ups were obtained at the next follow-up via the TLFB calendar method. Data on use of other drugs prior to each follow-up were obtained from the ASI.

2.6.2. Urine toxicology

Urine samples were obtained at baseline and at each follow-up point to provide a more objective measure of cocaine and other drug use (e.g., amphetamines, opiates, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, and THC). The samples were tested with a homogenous enzyme immunoassay method, with established cutoffs for drug positive results.

2.6.3. Outcome measures

Two primary outcomes were included: cocaine urine toxicology, and a dichotomous measure of good overall substance use outcomes (i.e., “abstinence composite”). To be considered abstinent on this measure in a given segment of the follow-up (3 month periods in months 1–12, 6 month periods in months 13–24), the participant had to have (1) no cocaine use, as indicated by self-report on the TLFB and urine toxicology; (2) no use of other drugs of abuse, as indicated by self-report on the ASI and urine toxicology; and (3) no heavy alcohol use as reported on the TLFB (i.e., 5 or more drinks/day for men, 4 or more drinks/day for women). A description of how the measure was operationalized is presented elsewhere (McKay et al., 2013).

2.7. Follow-Up Rates

The follow-up rates at each follow-up point were as follows: 3 months, 79.4%; 6 months, 76.9%; 9 months, 71.7%; 12 months, 72.9%; 18 months, 71.0%; and 24 months, 74.8%. When TLFB data from subsequent follow-up points were used to backfill prior missing follow-ups, the TLFB follow-up rates were: 3 months, 91.6%; 6 months, 90.0%; 9 months, 86.9%; 12 months, 85.0%; 18 months, 77.9%; and 24 months, 74.8%. The three treatment conditions did not differ significantly on follow-up rates at any point.

2.8. Data Analyses

Differences between the three conditions at baseline were evaluated with one-way ANOVAs (continuous measures) and chi-square tests (categorical measures). Treatment differences in number of days on which intensive outpatient treatment sessions were received were also evaluated with one-way ANOVAs.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE; SAS PROC GENMOD) were used to compare the continuing care conditions on the binary abstinence composite and urine toxicology outcome measures at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, and 24 months in intent-to-treat analyses. Time was modeled as a categorical factor with six levels. Preliminary analyses indicated site did not interact with treatment condition or the moderator variables, but it did predict both outcomes and so was included as a covariate in all analyses.

The moderator analyses included the moderator variable, moderator × treatment interactions, moderator × time interactions, and moderator × treatment × time interactions. However, the moderator × time and 3-way interactions did not approach significance in any of these analyses, and were therefore removed. Focused contrasts were used to compare the three treatment conditions at each level of the moderators. For continuous variables, analyses were done both with continuous scores and with dichotomous scored generated with median splits. Analyses with continuous and dichotomous versions of the moderators generated very similar results; results with the dichotomous versions are presented for ease of interpretation. For the four variables associated with larger treatment effects favoring TMC in a prior study (McKay et al., 2011), data plots were examined in the absence of statistically significant results to determine if the non-significant differences were in the same direction as in the prior study.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of Treatment Conditions on Moderators at Baseline

Participants in the three treatment conditions were compared on the 10 potential moderator variables. The groups differed on only one variable; the TAU and TMC+ conditions had higher rates of any days of depression than TMC (p= .045) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Moderator Variables

| TAU (N=108) | Treatment TMAC (N=106) | TMAC+ (N=107) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | % (N) | % (N) | % (N) | Chi-Sq | P-value |

| Gender (% male) | 75.9 (82) | 75.5 (80) | 77.6 (83) | 0.43 | .931 |

| In Controlled Environment prior to IOP | 19.4 (21) | 28.3 (30) | 26.2 (28) | 7.42 | .291 |

| Prior treatments (3 or more) | 51.9 (56) | 57.5 (61) | 55.1 (59) | 2.12 | .702 |

| High Readiness to Change | 49.1 (53) | 50.9 (54) | 51.4 (55) | 0.39 | .937 |

| Committed to Abstinence | 62.0 (67) | 66.0 (70) | 61.9 (66) | 1.51 | .777 |

| High Self Efficacy | 43.5 (47) | 50.0 (53) | 39.3 (42) | 7.58 | .283 |

| Any Days of Depression in prior 30 days | 44.4 (48) | 30.2 (32) | 44.9 (48) | 18.6 | .045 |

| High Psychiatric Problem Severity | 51.9 (56) | 43.4 (46) | 56.1 (60) | 10.6 | .170 |

| Network member encourages substance use | 17.6 (19) | 17.0 (18) | 19.6 (21) | 0.83 | .871 |

| High Family/Social Problem Severity | 47.2 (51) | 57.1 (61) | 45.3 (48) | 10.2 | .181 |

3.2. Participation in Outpatient Treatment

Over the first six months of the follow-up, participants averaged 30 days on which they received IOP or OP sessions, with no difference between the treatment conditions [mean days TAU = 30.8, TMC = 29.0, TMC+ = 30.5; F(2,281)= .38, p= .69].

3.3. Participation in TMC and TMC+

In TMC, 77 of 106 participants (72.6%) completed the orientation session and were eligible to receive continuing care sessions. In the TMC+ condition, 89 of the 107 participants (83.2%) completed orientation. The mean number of continuing care sessions received by participants who completed their orientations was 15.5 (SD= 14.1) in TMC and 26.0 (SD= 12.8) in TMC+. Participants in TMC+ who had completed an orientation earned an average of 24.7 vouchers (sd=13.7).

3.4. Moderator and Subgroup Effects with Baseline Variables

3.4.1. Gender

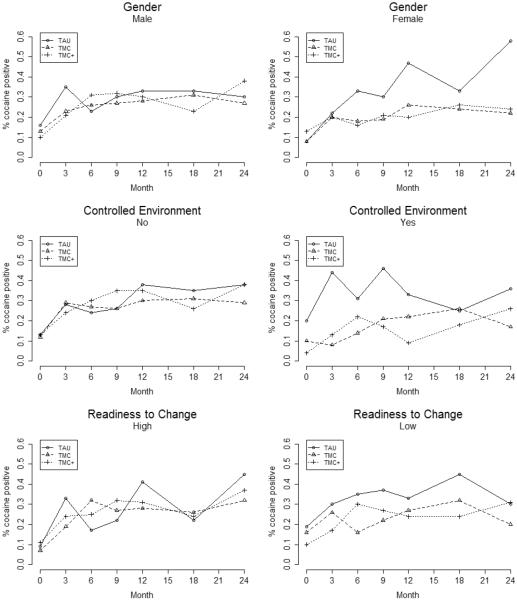

There were no significant main or moderator effects for gender with either outcome measure, and none of the treatment condition contrasts was significant. However, the size of the effects favoring extended continuing care over TAU observed on the cocaine urine toxicology outcome were somewhat larger in women than in men (TMC vs. TAU: women estimate = −.69, men estimate= −.21; TMC+ vs. TAU: women estimate= −.64, men estimate= −.11) (see Table 2). An examination of data plots indicated that rates of cocaine positive urines among women participants were about twice as high in TAU compared to the average of TMC and TMC+ at 6 months (33% vs. 17% positive), 12 months (47% vs. 23% positive), and 24 months (58% vs. 23% positive), with smaller differences in the same direction at the other follow-ups (mean of 16 percentage point difference across all follow-ups). At the final follow-up (24 months), cocaine urine positive rates in women were significantly higher in TAU than in TMC (p= .032). Conversely, the treatment conditions differed by only a few percentage points in men (see Figure 2).

Table 2.

Moderator Analyses with Demographic and Baseline Measures

| Moderator | Outcome | Moderator Main Effect | Moderator × Treatment Interaction | Moderator Level | TMC vs. TAU | TMC+ vs. TAU | TMC+ vs. TMC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EST | P | EST | P | EST | P | |||||

| Gender | Abst Comp | x2= 0.06 | x2= 0.42 | Men | .25 | .31 | .05 | .83 | −.19 | .42 |

| Women | .00 | .99 | .11 | .80 | .12 | .80 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 0.83 | x2= 1.16 | Men | −.21 | .43 | −.11 | .67 | .10 | .69 | |

| Women | −.69 | .16 | −.64 | .20 | .05 | .93 | ||||

| Controlled Environment | Abst Comp | x2= 7.11** | x2= 0.43 | No | .05 | .84 | −.05 | .83 | −.10 | .69 |

| Yes | .35 | .41 | .22 | .62 | −.13 | .74 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 5.03* | x2= 3.39 | No | −.12 | .65 | .04 | .88 | .15 | .56 | |

| Yes | −1.00 | .07 | −1.05 | .04 | −.04 | .93 | ||||

| Prior Drug Treatments | Abst Comp | x2= 3.69+ | x2= 2.96 | Low | .41 | .20 | .48 | .14 | .07 | .84 |

| High | .04 | .89 | −.27 | .33 | −.31 | .24 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 0.17 | x2= 0.20 | Low | −.29 | .43 | −.30 | .41 | −.01 | .98 | |

| High | −.41 | .17 | −.21 | .45 | .21 | .49 | ||||

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01

Figure 2.

Moderator Effects

Treatment group effects separated by gender (male, female), controlled environment (no, yes), and readiness to change (high, low) on cocaine urine toxicology outcomes are presented.

3.4.2. Controlled environment

Participants who had been in a controlled environment prior to IOP had better outcomes on the abstinence composite (p< .01) and on cocaine urine toxicology (p< .05). The controlled environment x treatment condition interaction was not significant with either outcome. However, in participants who had been in a controlled environment, there were effects on cocaine urine toxicology favoring TMC+ over TAU (p= .04) and TMC over TAU (p= .07) (see Table 2). Examination of data plots indicated that among participants who had been in a controlled environment prior to IOP, rates of cocaine positive urines obtained at the 3, 6, 9, and 12 month follow-ups were 15–33 percentage points higher in TAU compared to the average of TMC and TMC+. Conversely, the treatment conditions differed by only a few percentage points in those who had not been in a controlled environment (see Figure 2).

3.4.3. Prior drug treatments

A greater number of prior drug treatments predicted lower abstinence rates on the composite outcome, but only at the level of a trend, and the measure was unrelated to cocaine urine toxicology. Moderator effects and treatment condition contrast effects were not significance. (see Table 2).

3.5. Moderator and Subgroup Effects with Measures of Progress in IOP

3.5.1. Cognitive and motivational factors

Readiness to change and commitment to abstinence did not predict either outcome or interact significantly with treatment condition in moderator analyses, and focused treatment contrasts were also not significant. However, the size of the effects favoring extended continuing care over TAU observed on the cocaine urine toxicology outcome were somewhat larger in participants with low vs. high readiness to change (TMC vs. TAU; low readiness estimate= −.51, high readiness estimate= −.18; TMC+ vs. TAU: low readiness estimate= −.37, estimate z= −.09) (see Table 3). Data plots indicate that rates of cocaine positive urines among participants with low readiness to change were 8–17 percentage points higher in TAU compared to the average of TMC and TMC+ across months 3–18. Conversely, the treatment conditions differed by only a few percentage points in those with high readiness to change (see Figure 2). A similar pattern was found with commitment to abstinence, in which abstinence composite scores in months 12–24 favored TMC over TAU by about 10 percentage points in participants who were not committed to abstinence at baseline, whereas there was no difference in those committed to abstinence.

Table 3.

Moderator Analyses with Measures of IOP progress

| Moderator | Outcome | Moderator Main Effect | Moderator × Treatment Interaction | Moderator Level | TMC vs. TAU | TMC vs. TAU | TMC+ vs. TMC | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EST | p | EST | P | EST | P | |||||

| Readiness to Change | Abst Comp | x2= 0.01 | x2= 0.22 | Low | .13 | .65 | .11 | .71 | −.02 | .95 |

| High | .22 | .44 | .01 | .98 | −.22 | .45 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 0.74 | x2= 0.61 | Low | −.51 | .13 | −.37 | .25 | .13 | .69 | |

| High | −.18 | .60 | −.09 | .77 | .09 | .79 | ||||

| Commitment to Abstinence | Abst Comp | x2= 1.18 | x2= 1.88 | No | .37 | .27 | −.15 | .68 | −.53 | .16 |

| Yes | .08 | .77 | .17 | .52 | .09 | .72 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 0.39 | x2= 0.73 | No | −.36 | .36 | −.01 | .98 | .35 | .37 | |

| Yes | −.34 | .23 | −.36 | .19 | −.01 | .96 | ||||

| Self Efficacy | Abst Comp | x2= 9.99** | x2= 4.20 | Low | .05 | .86 | −.36 | .22 | −.42 | .18 |

| High | .22 | .44 | .47 | .13 | .25 | .40 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 10.31** | x2= 2.55 | Low | −.26 | .42 | .04 | .89 | .30 | .35 | |

| High | −.36 | .30 | −.63 | .07 | −.27 | .46 | ||||

| Days with Depression | Abst Comp | x2= 1.44 | x2= 6.07 | No | .18 | .50 | .46 | .11 | .28 | .30 |

| Yes | .22 | .51 | −.46 | .16 | −.68 | .04 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 0.10 | x2= 3.78 | No | −.46 | .12 | −.63 | .03 | −.17 | .57 | |

| Yes | −.25 | .51 | .23 | .50 | .48 | .21 | ||||

| Psychiatric Severity | Abst Comp | x2= 0.34 | x2= 0.34 | Low | .26 | .36 | .19 | .55 | −.07 | .81 |

| High | .11 | .72 | −.06 | .84 | −.17 | .57 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 4.06* | x2= 0.08 | Low | −.30 | .33 | −.18 | .56 | .12 | .70 | |

| High | −.43 | .23 | −.22 | .50 | .21 | .56 | ||||

| Social Support for Substance Use | Abst Comp | x2= 0.00 | x2=1.06 | No | .11 | .64 | .09 | .69 | −.01 | .96 |

| Yes | .53 | .30 | −.04 | .94 | −.56 | .27 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 1.69 | x2= 0.50 | No | −.33 | .20 | −.32 | .20 | .01 | .98 | |

| Yes | −.41 | .46 | −.03 | .94 | .38 | .47 | ||||

| Family/Social Severity | Abst Comp | x2= 3.07+ | x2= 2.88 | Low | −.17 | .59 | −.24 | .40 | −.07 | .81 |

| High | .49 | .08 | .32 | .32 | −.17 | .57 | ||||

| Urine Tox | x2= 0.07 | x2= 3.32 | Low | −.39 | .29 | .12 | .70 | .51 | .16 | |

| High | −.34 | .26 | −.59 | .06 | −.25 | .45 | ||||

Higher self-efficacy strongly predicted higher abstinence rates on the composite and lower cocaine positive urine toxicology rates (both ps < .01). However, the self-efficacy by treatment condition interactions were not significant, and there was no evidence that TMC or TMC+ was better than TAU for participants with low self-efficacy. In fact, in patients with high self-efficacy both treatments produced somewhat better outcomes on both measures than TAU, although none of these results was significant at the p< .05 level (see Table 3). In participants with high self-efficacy, for example, rates of cocaine positive urines averaged 12 percentage points higher in TAU than in TMC+ across the follow-ups (p< .10).

3.5.2. Psychiatric factors

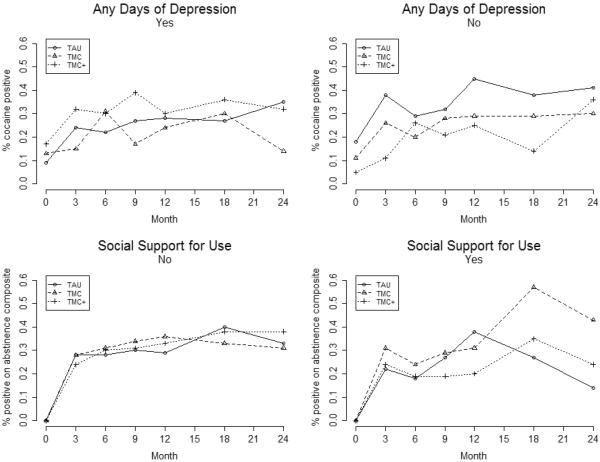

Higher scores on the ASI psychiatric severity composite predicted lower rates of cocaine positive urine tests (p< .05), but there were no other main effects on the psychiatric composite or days of depression variable. None of the interactions between the two psychiatric measures and treatment condition was significant with either outcome (see Table 3). The focused contrasts indicated that in participants with no days of depression, TMC+ was superior to TAU on the cocaine urine toxicology outcome by an average of 15 percentage points across the follow-ups (p= .03). Conversely, in participants with days of depression, TMC was superior to TMC+ on the abstinence composite (p= .04) (see Figure 3). There were no treatment effects in either the low or high ASI psychiatric severity groups.

Figure 3.

Moderator Effects

Treatment group effects separated by any days of depression (yes, no), and social support for use (no, yes) on cocaine urine toxicology and abstinence composite outcomes, respectively, are presented.

3.5.3. Family-social factors

Social support for continued substance use did not predict either outcome measure and did not interact with treatment condition to predict outcomes, and the focused treatment contrast effects were also not significant (see Table 3). However, an examination of data plots indicated that in participants with social support for continued use, scores were much higher on the abstinence composite in TMC than in TAU at 18 months (57% vs. 27% abstinent) and at 24 months (43% vs. 14% abstinent). With the small sample size, neither of these differences was significant (both p= .13). Conversely, there were no differences between the treatment conditions in those who did not have social support for continued use (see Figure 3). However, these results were not obtained on the cocaine urine toxicology outcome.

Higher ASI family/social composite scores predicted lower rates of abstinence on the composite at the level of a trend. Interactions between this severity measure and treatment condition were not significant. However, in patients with higher family/social problem severity, there were trends favoring TMC over TAU on the abstinence composite (average 7 percentage point difference across the follow-ups), and TMC+ over TAU on cocaine urine toxicology (average of 9 percentage points across the follow-ups). Conversely, in those with low family/social problem severity, there was less or no advantage for TMC and TMC+ over TAU.

4. Discussion

This article examined potential moderators of response to extended continuing care interventions in cocaine dependent patients enrolled in publicly funded IOPs. A prior report from the study found that IOP plus the continuing care interventions was more effective than IOP only for patients who were using any cocaine or alcohol immediately prior to intake or during the first three weeks of IOP. Conversely, there were no treatment effects in patients who were not using any cocaine and alcohol during this period (McKay et al., 2013).

Here, we attempted to replicate findings from a prior continuing care study in which IOP plus extended continuing care was found to be more effective than IOP only for women and for individuals with prior treatments for substance use disorders, and for those with lower readiness to change or social support for continued use after 3–4 weeks of IOP (McKay et al., 2011). The potential moderating effects of several other measures of IOP progress and being in a controlled environment prior to IOP were also considered.

None of the four measures found to predict larger extended continuing care effects in our prior study with alcohol dependent patients (McKay et al., 2011) significantly moderated continuing care effects in the present study, or generated significant treatment effects in predicted subgroups. However, our ability to find significant effects for women and those with social support for continued substance use was greatly limited due to small numbers of participants in these groups (i.e., low power). An examination of data plots indicated that in women, rates of cocaine positive urines across the follow-up were about twice as high in TAU as in TMC and TMC+, which is about the size of the differences in women on alcohol use outcomes favoring TMC over TAU obtained in our prior study. Moreover, in women the rate of cocaine positive urines at the end of the follow-up was significantly lower in TMC than in TAU. However, the same effects were not obtained on the abstinence composite outcome. Similarly, a large difference favoring TMC over TAU on the abstinence composite was obtained in the second year of the follow-up in those who had social support for continued substance use early in IOP. However, this effect was not found with the cocaine urine toxicology outcome or in the TMC+ vs. TAU comparisons on either outcome. Finally, there was little evidence of any moderation with low readiness to change or prior treatments for drug dependence.

Of the other five measures of progress toward IOP goals that were examined, self-efficacy was most strongly related to outcome, with higher scores predicting better scores on both outcome measures. This is a common finding in studies of treatments for substance use disorders (Maisto, Connors, & Zywiak, 2000; McKay, 1999; Witkiewitz & Marlatt, 2004). However, there was no evidence that participants with low self-efficacy or those who were not committed to abstinence benefited to a greater degree from extended continuing care. However, results at the level of a trend indicated that participants with higher family/social problem severity had better outcomes on the abstinence composite if they received TMC rather than TAU, and better outcomes on cocaine urine toxicology if they received TMC+ rather than TAU.

Analyses with the psychiatric factors measures produced surprising results. Higher scores on the ASI measure of general psychiatric severity or distress predicted lower rates of cocaine positive urines. In addition, effects favoring extended continuing care with incentives were found in those who reported no days of depression at baseline, again contrary to expectations. It is possible that patients with particularly high psychiatric severity dropped out of the IOP before becoming eligible for the study after 2 weeks in treatment. In patients who were able to enter the study, psychiatric distress may have prompted greater participation in treatment, without being so severe as to interfere with treatment engagement or participation. With regard to the treatment effect, it is possible that non-depressed patients were more responsive to the incentives in TMC+ condition, as the same effect was not obtained in TMC. However, these are just speculations, and further work is necessary to better understand the relation of psychiatric severity early in treatment to continuing care effects.

The other variable examined—controlled environment prior to IOP—predicted outcome and showed evidence of subgroup effects. In participants who had been in a controlled environment right before IOP, TMC+ produced lower rates of cocaine positive urines than TAU, and similar results at the level of a trend were obtained in the comparison of TMC and TAU. We had expected that being in a controlled environment prior to IOP would be a proxy for greater substance use or other problem severity, which is why we predicted that it would moderate continuing care effects. However, being in a controlled environment predicted better, rather than worse, substance use outcomes. It may be that the controlled environment stabilized patients prior to IOP, thereby improving retention and overall outcomes. In any case, additional work is needed to fully understand why extended continuing care was beneficial to those who had been in controlled environments prior to IOP.

4.1. Treatment Recommendations

The results from this study presented here and in another report (McKay et al., 2013) suggest that the strongest determinant of need for extended continuing care in cocaine dependent patients is failure to achieve abstinence from cocaine and alcohol immediately prior to and during the first few weeks of IOP. This replicates findings from two prior studies with cocaine dependent IOP patients, in which effects favoring more intensive vs. less intensive continuing care were obtained in patients who used cocaine or alcohol early in IOP (McKay et al., 1999; McKay et al., 2005). Conversely, other measures of treatment progress, demographics, and measures of pretreatment characteristics appear to be of limited value in determining need for extended continuing care. However, more work is needed on the potential moderating effects of gender and poor social support (i.e., social support for substance use and family/social problem severity) on the need for extended continuing care for cocaine dependence, given the direction of effects observed in this study, limited power for those analyses due to low numbers of women and of those with a significant other who encouraged further substance use, and significant effects in our prior study (McKay et al., 2011).

4.2. Study Strengths and Limitations

The study had a number of strengths, including a randomized design, the inclusion of patients from “real world” publicly funded addiction treatment programs, a relatively large sample size, documented adherence to the treatment manuals (Carroll et al., 2000), availability of both self-report and biological outcome data, six outcome assessments over a 24 month period, and a good follow-up rate. At the same time, the study had several limitations. It is not clear whether the same results would have been obtained with patients who were receiving standard rather than intensive outpatient treatment, or in patients in IOPs that were of shorter duration than the IOPs that participated in this study. However, moderator effects might actually be larger in standard outpatient or shorter IOPs, in which patients receive considerably less treatment than those randomized to standard care in this study.

Participants were given the option of attending some continuing care sessions in person, rather than over the telephone. Over 40% of the sessions were completed in person, which speaks to the appeal of face-to-face contact with a counselor. We therefore tested hybrid models of continuing care, which included both telephone and face-to-face sessions. The same results might not have been obtained in a pure call center model, in which all sessions are provided over the telephone. Finally, the results in the present study were obtained in participants who managed to complete at least two weeks of IOP. It is not clear that same results would have been obtained with patients who drop out of IOP in the first two weeks.

4.3. Conclusions

Two of the goals of new health care legislation, such as the Affordable Care Act, are to improve treatment outcomes and control costs. In addiction treatment, progress toward these goals can be achieved by identifying patients who are greatest risk for relapse and providing extended continuing care to them. There is mounting evidence that cocaine or alcohol dependence patients with greater problem severity or continued use early in treatment benefit more from extended continuing care than do others, and that women may as well (Dennis & Scott, 2012; McKay et al., in press; McKay et al., 1999; McKay et al., 2011; O'Farrell et al., 1998). Further work is needed to replicate and more fully clarify these results, and to identify other factors that predict need for extended support.

Highlights

Patients in a controlled environment prior to treatment benefited from continuing care.

Patients with poor social support appeared to benefit more from continuing care.

Women benefited more from continuing care than men, but results were not significant.

Substance use early in treatment is best predictor of who will benefit from continuing care.

Acknowledgements

We thank the management and clinical staffs at NorthEast Treatment Centers and Presbyterian Hospital for collaborating on this research project and providing access to patients in their programs. We thank the therapists who provided the continuing care interventions in the study. Finally, we thank Lior Rennert for preparing the figures presented in the manuscript.

Role of Funding Sources This research was supported by grants R01 DA020623, K02 DA000361, and K24 DA029062 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. Additional support was provided by the Medical Research Service and the SUD QUERI of the Department of Veterans Affairs. These funding agencies had no role in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; writing the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors McKay, Lynch, and Van Horn designed the study. McKay, Van Horn, Coviello, and Ivey wrote the protocol. Van Horn, Ivey, Coviello, and Drapkin conducted the study, supervised therapists and research technicians, and conducted literature searches. Lynch, Van Horn, and Cary conducted the data analyses. McKay wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and all other authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

References

- Annis HM, Martin G. The Drug-Taking Confidence Questionnaire. Addiction Research Foundation of Ontario; Toronto, Ontario, Canada: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Sifry RL, Nuro KF, Frankforter TL, Ball SA, Fenton L, Rounsaville BJ. A general system for evaluating therapist adherence and competence in psychotherapy research in the addictions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2000;57:225–238. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addiction Science and Clinical Practice. 2007 Dec;:45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK. Four-year outcomes from the Early Re-Intervention (ERI) experiment using Recovery Management Checkups (RMCs) Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012;121:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrman RN, Robbins SJ. Reliability and validity of six-month timeline reports of cocaine and heroin use in a methadone population. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:843–850. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Stewart W, O'Farrell TJ, Freitas TT, McFarlin SK, Rutigliano P. The timeline followback reports of psychoactive substance use by drug-abusing patients: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:134–144. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders—patient edition (SCID-I/P, version 2.0) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hall SM, Havassy BE, Wasserman DA. Effects of commitment to abstinence, positive moods, stress, and coping on relapse to cocaine use. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:526–532. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Longshore D, Anglin MD. The life course perspective on drug use: a conceptual framework for understanding drug use trajectories. Evaluation Review: A journal of Applied Social Research. 2007;31:515–547. doi: 10.1177/0193841X07307316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Connors GJ, Zywiak WH. Alcohol treatment, changes in coping skills, self-efficacy, and levels of alcohol use and related problems 1 year following treatment initiation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14:257–266. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisto SA, Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Comparison of alcoholics' self-reports of drinking behavior with reports of collateral informants. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:106–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR. Studies of factors in relapse to alcohol and drug use: A critical review of methodologies and findings. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1999;60:566–576. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1999.60.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR. Continuing care research: What we've learned and where we're going. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Alterman AI, Cacciola JS, O'Brien CP, Koppenhaver JM, Shepard Continuing care for cocaine dependence: Comprehensive 2-year outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:420–427. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Lynch KG, Shepard DS, Pettinati HM. The effectiveness of telephone based continuing care for alcohol and cocaine dependence: 24 month outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:199–207. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Van Horn D, Lynch KG, Ivey M, Cary MS, Drapkin M, Coviello D, Plebani JG. An adaptive approach for identifying cocaine dependent patients who benefit from extended continuing care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0034265. ePub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Van Horn D, Oslin D, Ivey M, Drapkin M, Coviello D, Yu G, Lynch KG. Extended telephone-based continuing care for alcohol dependence: 24 month outcomes and subgroup analyses. Addiction. 2011;106:1760–1769. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03483.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Van Horn D, Oslin D, Lynch KG, Ivey M, Ward K, Drapkin M, Becher J, Coviello D. A randomized trial of extended telephone-based continuing care for alcohol dependence: Within treatment substance use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:912–923. doi: 10.1037/a0020700. PMCID: PMC3082847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: Implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Cacciola J, Griffith J, Evans F, Barr H, O'Brien CP. New data from the Addiction Severity Index: Reliability and validity in three centers. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1985;173:412–423. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Luborsky L, Woody GE, O'Brien CP. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients: The Addiction Severity Index. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Farrell TJ, Choquette KA, Cutter HSG. Couples relapse prevention sessions after behavioral marital therapy for male alcoholics: Outcomes during the three years after starting treatment. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1998;59:357–370. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1998.59.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente C. The Transtheoretical Approach: Crossing The Traditional Boundaries of Therapy. Krieger Publishing Co.; Malabar, FL: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Results from two randomized clinical trials evaluating the impact of quarterly recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users. Addiction. 2009;104:959–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Maisto SA, Sobell MB, Cooper AM. Reliability of alcohol abusers' self-reports of drinking behavior. Behavior Research and Therapy. 1979;17:157–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(79)90025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout RL, Beattie MC, Longabaugh R, Noel N. Factors affecting correspondence between patient and significant other reports of drinking. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1989;12:336. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn DHA, Drapkin M, Ivey M, Thomas T, Domis SW, Abdalla O, Herd D, McKay JR. Voucher incentives increase treatment participation in telephone-based continuing care for cocaine dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;114:225–228. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.09.007. PMCID: PMC3046319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for alcohol and drug problems: That was Zen, this is Tao. American Psychologist. 2004;59:224–235. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.4.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak WH, Neighbors CJ, Martin RA, Johnson JE, Eaton CA, Rohsenow DJ. The Important People Drug and Alcohol interview: psychometric properties, predictive validity, and implications for treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:321–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]