Abstract

The rise in antimicrobial drug resistance, alongside the failure of conventional research to discover new antibiotics, will inevitably lead to a public health crisis that can drastically curtail our ability to combat infectious disease. Thus, there is a great global health need for development of antimicrobial countermeasures that target novel cell molecules or processes. RNA represents a largely unexploited category of potential targets for antimicrobial design. For decades, control of cellular behavior was thought to be the exclusive purview of protein-based regulators. The recent discovery of small RNAs (sRNAs) as a universal class of powerful RNA-based regulatory biomolecules has the potential to revolutionize our understanding of gene regulation in practically all biological functions. In general, sRNAs regulate gene expression by base-pairing with multiple downstream target mRNAs to prevent translation of mRNA into protein. In this review, we will discuss recent studies that document discovery of bacterial, viral, and human sRNAs and their molecular mechanisms in regulation of pathogen virulence and host immunity. Illuminating the functional roles of sRNAs in virulence and host immunity can provide the fundamental knowledge for development of next-generation antibiotics using sRNAs as novel targets.

Keywords: sRNA, miRNA, bacterial pathogens, viral pathogens, host immune response, Hfq, virulence

Introduction

One of the greatest mysteries in modern molecular biology is the functional role of the 3 billion DNA bases in our human genome. Based on the sequencing results of the Human Genome Project, <2% of our DNA is predicted to be genes that encode for proteins, long thought to be the primary blueprint for life. The remaining ~98% of the genome had been pejoratively labeled “junk” DNA to connote the notion that intergenic DNA sequences had no useful function. This perception stems from the beginning of the molecular biology age in the late 1950s when Francis Crick, one of the co-discoverers of the DNA double helix structure, first coined the term “Central Dogma” to summarize the concept that genetic information flow in cells is essentially one-way, from DNA to RNA to protein. In the intervening years, research efforts were directed primarily toward understanding the function of proteins in such essential cellular processes as enzyme catalysis and cellular structure. In general, RNA was relegated to a role as an intermediate in transcription and translation to convert the nucleotide language of DNA into the amino acid language of proteins.

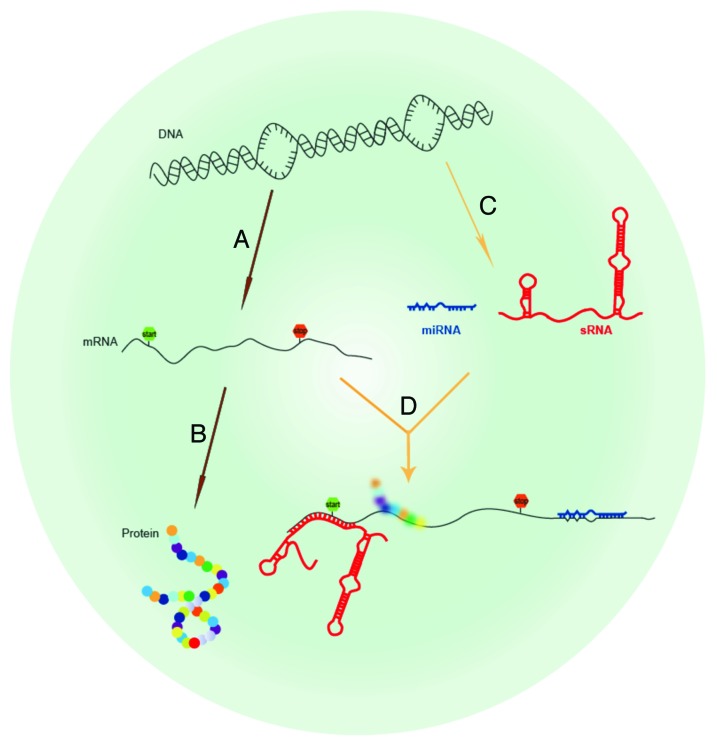

In the past 15 years, discovery of a new class of regulatory biomolecules, termed small RNAs (sRNAs), has challenged the long-held perception that proteins are the predominant regulators of gene expression.1,2 sRNAs have been found in diverse organisms from bacteria to plants to man, and are primarily encoded in intergenic space. Bacterial sRNAs vary from ~50 to 450 nucleotides, whereas eukaryotic sRNAs, also termed microRNAs (miRNAs), are processed into short ~22–25 nucleotide sequences. Many sRNAs function as gene regulators by base-pairing with the 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of target mRNAs to attenuate translation of mRNA into protein at the post-transcriptional level. (Fig. 1) By modulating the expression levels of target genes, a unique profile of sRNAs can enable precise gene regulation and rapid adaptation of cellular physiology in response to specific environmental changes. In our own studies, we have developed a single molecule fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) method to quantify specific sRNA levels in Yersinia pestis.3 Using an automated multi-color wide-field microscope, we observed that a temperature shift to 37 °C to simulate the human host resulted in a ~3.5-fold increase in the number of Y. pestis expressing the novel sRNA ysp8, suggesting that ysp8 may play a role in pathogenesis during host infection. These deliberate changes in sRNA expression can modulate pathogenicity by regulating virulence factors such as the Type III secretion system, quorum sensing, or iron transport.

Figure 1. Overview of regulatory RNA. (A) Protein-coding genes in DNA can be transcribed into mRNA (mRNA) and then (B) translated into protein. Regulatory RNAs are a novel class of RNA that do not encode protein but act as regulators of gene expression. (C) Regulatory RNAs, either eukaryotic miRNAs (blue) or prokaryotic sRNAs (red) are transcribed from the genome, and (D) regulate translation of other protein coding genes by base pairing with 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions of their cognate mRNA targets.

In this review, we will discuss bacterial, viral, and human sRNAs and their respective roles in pathogen virulence and host immunity. (See Table 1 for summary of sRNAs.) While discovery of pathogen sRNAs and their cognate functions are rapidly growing fields, a number of cancer studies have already established human miRNAs as potential biomarkers for distinguishing healthy tissue from malignant tumors in different types of cancer. To date, ~25 000 miRNA transcripts from 193 species, including ~1600 from humans, have been entered into the Sanger miRBase database release 19 (http://www.mirbase.org).4-7 Only ten years earlier, this database began with 218 entries. This exponential discovery of sRNAs far outpaces functional discovery, and thus the great majority of sRNAs have not yet been validated for function. We will describe the current state of sRNA discovery and functional analysis in pathogens and human immune defense and discuss sRNAs as potential novel targets to combat infectious disease by modulating pathogenicity or the host inflammatory response.

Table 1. Diverse mechanisms of sRNA function in bacteria, host, and virus during host–pathogen interactions.

| Organism | sRNA | Mechanism | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial pathogens | |||

| Y. pestis | ysp8 | Overexpression at 37 °C, analysis by smFISH | 3 |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis, Y. pestis | ysr35 | Virulence determinant in pathogenic Yersinia | 21 |

| Y. pestis | gcvB | Encodes two sRNAs that regulate membrane transport | 25 |

| E. coli, Y. pestis | sgrS | Expressed under conditions of metabolic stress | 26 |

| Y. pseudotuberculosis | csrB/C | Activates expression of the global virulence regulator RovA | 27 |

| F. tularensis | FtrC | Regulates replication of the bacterium | 29 |

| B. abortus | abcR1, abcR2 | Regulates metabolism genes required for intracellular survival | 30 |

| X. campestris | sX12 | Affects disease symptoms in the plant host | 31 |

| E. amylovora | RyhA, RprA | Affects lesion size in the plant host | 32 |

| Host | |||

| A. thaliana | miR393a | Mediates resistance against P. syringae infection | 58 |

| Human/mouse | miR-146 | Upregulated during infection by multiple bacteria and influenza; regulates innate immunity and inflammatory responses; targets TRAF6 and IRAK1 | 59–63, and 106 |

| Human | miR-155 | Upregulated in response to bacterial and viral antigens; regulates cytokine production and adaptive immunity | 59, 62, 64–70, and 74-79 |

| Human | miR-371–372–373 | Implicated in H. pylori infection | 71 |

| Human | miR-21 | Implicated in H. pylori infection | 72 |

| Human | miR-223 | Implicated in H. pylori and TB infection; indicator of sepsis; modulates neutrophil activation during influenza infection | 73, 81, and 105 |

| Human | miR-125b | Negative regulator of TLR pathway; targets TNF-α | 64 and 80 |

| Human | let-7 | Downregulated in response to infection by multiple pathogens; targets TLR4; upregulated in response to RSV | 82–85 |

| Human | miR-29a | Inhibit HIV production | 102 |

| Human | miR-200a | Modulates JAK-STAT pathway in response to influenza infection | 105 |

| Human | miR-451 | Suppresses host cytokine production in dendritic cells during influenza infection; role in TB infection | 81 and 107 |

| Viral pathogens | |||

| Adenovirus | VA1 and VA2 | Suppresses host translation | 96 |

| Epstein–Barr virus | EBER1 and EBER2 | Suppresses host translation | 97 |

| Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus | KSHV-miR-K11–12 | Shares 100% seed sequence similarity with miR-155 and modulates host immune response | 100 |

| HIV | tRNALys3, tRNALys5a | Acts as primers for HIV RT polymerase and slows host protein synthesis | 101 |

| Influenza | svRNAs | Required for viral RNA production | 104 |

| CaMV | sRCC1 | Promote cleavage of Atlg76950 during infection of Arabidopsis | 108 |

Identification and Analysis of sRNAs

Highly-expressed sRNAs, such as 4.5S, transfer-messenger (tmRNA), RNaseP, and Spot 42, were first discovered fortuitously in 1971 in E. coli using metabolic radiolabeling with 32P orthophosphate of the total RNA population.8 These sRNAs were initially thought to be precursors for tRNAs, and their roles in key housekeeping functions were not elucidated until decades later. Other early labor-intensive and low-to-moderate throughput approaches to identify novel sRNAs included shotgun cloning of cDNAs generated from expressed RNA transcripts followed by traditional sequencing, and DNA microarray analysis printed with probes to inter-genic regions.9

Currently, ultra high-throughput sequencing is revolutionizing whole genome and transcriptomics analysis, including identification of novel sRNAs in intergenic space. This approach is often combined with co-immunoprecipitation of the bacterial RNA-binding protein Hfq, which facilitates binding between many sRNAs and their cognate mRNAs, to enrich RNA preparation for downstream sRNA sequencing and identification.10 Per sequencing run, millions of reads can be mapped to intergenic space, thus allowing for deeper probing of sRNA populations than has previously been possible. High-throughput sequencing has also enabled analysis of sRNA expression in bacteria grown under different conditions or between closely related species. A comparative transcriptomics analysis of Burkholderia cenocepacia grown in two different ecological niches, a soil environment and an infection model, revealed that the sRNA expression profiles differed between the two growth conditions.11 A B. cenocepacia sRNA that exhibited bactericidal activity was found to be present only in some members of the Burkholderia species but not in near neighbors, suggesting that unique sRNA sequences in closely related pathogens can be used to establish robust transcriptomic signatures.

For eukaryotes, host miRNA expression can also be analyzed using commercially-available microarrays, which contain probes against all known human miRNAs. Although this method cannot uncover novel miRNAs, the microarrays provide a cost-effective and standardized platform for comparing eukaryotic sRNA expression in response to different stimuli or cell types.

Bioinformatics approaches have also been applied to identification of bacterial sRNAs using such parameters as secondary structure, thermodynamic stability, transcriptional signals, specific structural elements such as atypical GC content, and comparative genomics.12,13 However, computational prediction of sRNAs remains challenging because sRNAs are diverse in length, do not appear to have a common secondary structure, and are not well conserved even across related species. Methods that rely on conservation of sRNA sequence and/or structure would most likely miss more unique, species-specific sRNAs. Given that false positives are common among bioinformatics methods, experimentation is always required to validate sRNA candidates. For example, the behavioral responses of bacteria deficient for a target sRNA by either gene knockout or knockdown can be compared with wild-type bacteria to validate sRNA functional roles.

Pathogen sRNA Function in Virulence

Bacterial sRNAs have been implicated in a wide variety of cellular functions in physiology, including both conserved housekeeping functions, such as tRNA processing and the secretory pathway, and more specialized functions, such as quorum sensing or virulence. sRNAs are classified into three functional groups: (1) cis-coded sRNAs that regulate an adjacent gene, (2) trans-coded sRNAs that bind to multiple targets in distant sites in the genome, and (3) sRNAs that bind to proteins in order to regulate a target. In bacteria, the RNA chaperone Hfq facilitates binding between many sRNAs and their cognate mRNAs to strengthen interactions that are often dependent on short stretches of imperfect base pairing. Homologs of Hfq are found in diverse bacterial species, including pathogenic Salmonella, Yersinia, and Burkholderia species.14,15 Consistent with a critical role in sRNA-mediated gene regulation, deletion or mutation of hfq leads to pleiotropic effects or significant attenuation of virulence. A Y. pestis mutant deleted for hfq exhibited attenuated infection in mice and marked alterations in expression of many stress resistance and virulence genes.16 An hfq mutant in Brucella abortus also displayed extreme attenuation in mice, increased sensitivity to oxidative stress and starvation conditions, and decreased survival in low pH, compared with the parental strain.17 Hfq also promotes resistance to osmotic and membrane stresses in Franciscella tularensis and is required for the ability of the vaccine strain F. tularensis LVS to induce disease in a mouse model.18 However, there are also examples of sRNAs that do not appear to require Hfq. For example, deletion of hfq in Staphylococcus aureus and Listeria monocytogenes did not appear to affect overall sRNA expression levels or function.19,20

Bacterial sRNA discovery and validation

As aforementioned, deep sequencing has become the method of choice for discovery of novel sRNAs. In Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, ~150 previously-unknown sRNAs were found to be expressed at the human host temperature of 37 °C, compared with the flea host temperature of 26 °C.21 The majority of these sRNAs are conserved between Y. pseudotuberculosis and its close relative, Y. pestis, the causative agent of plague. However, the timing of sRNA expression and functional dependence on Hfq was shown to differ, suggesting that subtle differences in posttranscriptional gene regulation exist between the two pathogenic Yersinia species. Deletion of a specific sRNA, Ysr35, in both Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis significantly attenuated survival in a mouse model compared with a virulent wild-type strain, strongly suggesting that Ysr35 is required for Yersinia adaptation to the host. Deletion of three other sRNAs in Y. pseudotuberculosis also led to attenuation of infection in mice. Since this initial work, two other studies have also described identification of Yersinia sRNAs. In one study using deep sequencing, 17 out of 31 candidate Y. pestis sRNAs were found to overlap with the ~150 Y. pseudotuberculosis sRNAs,22 whereas there was no overlap at all in sRNA identity in the second study, which employed cDNA cloning methods in human-avirulent Y. pestis.23 These variable results illustrate that individual sRNA expression levels are likely to be highly dependent on specific experimental conditions and underscores the importance of sRNA validation using northern blot to prevent false positives.

To attempt to quantify the copy number of specific bacterial sRNAs, our lab has also employed ultra high-throughput sequencing to identify novel sRNAs in Yersinia and modified a smFISH imaging method to quantitatively detect a novel sRNA termed ysp8, which is overexpressed at the human host temperature of 37 °C compared with 26 °C.3 We found that a small fraction (~20%) of Y. pestis express ysp8, with a copy number between 0 and 10 transcripts. This observation suggests that very low levels of sRNAs may be enough to regulate target mRNA populations at any given time. Interestingly, ~20% of E. coli proteins are present at one copy number or less, supporting a model in which low copy numbers of biomolecules are sufficient to maintain cellular functions.24

Other sRNAs have been previously identified in pathogenic Yersinia based on sequence homology with known E. coli sRNAs, including gcvB, sgrS, and csrB/C. Although these sRNAs regulate various aspects of bacterial metabolism rather than virulence, they nevertheless can be exploited for antimicrobial development to inhibit bacterial growth or survival. Y. pestis gcvB encodes two sRNAs that regulate dppA, the periplasmic-binding protein component of the dipeptide transport system.25 Deletion of gcvB altered the Y. pestis growth rate and colony morphology, pleiotropic phenotypes that indicate gcvB most likely regulates multiple downstream genes, in addition to dppA. The sRNA sgrS is expressed under conditions of metabolic stress when E. coli is unable to metabolize phosphorylated sugars. A Y. pestis sgrS ortholog has been shown to complement an E. coli sgrS mutant, indicating a conservation of function in regulation of target gene expression.26 Finally, the csrB/C sRNA has been shown to activate expression of the global virulence regulator RovA in Y. pseudotuberculosis.27

In S. pneumoniae, 56 novel sRNAs were identified using whole genome transcriptional sequencing.28 Fifteen sRNAs were chosen based on a favorable predicted free energy of folding and high levels of expression, as determined by northern blot, and further subjected to targeted deletion to validate sRNA function in virulence. Mutant S. pneumoniae strains that contained knockouts for eight of the sRNAs exhibited attenuation of sepsis in a murine model of infection by intranasal challenge, indicating that the selected sRNAs were required for virulence. A Tn-Seq approach was also applied to assess the relative fitness of sRNA mutants at three different host sites vital for progression of pneumococcal disease, including the nasopharynx, lungs, and the bloodstream. Unique sRNAs were found to play key roles in each of these specific tissues during infection.

Specific sRNAs have also been implicated in virulence in other pathogens. In the intracellular pathogen F. tularensis, high levels of the sRNA ftrC were shown to downregulate bacterial replication and reduce levels of bacteria in organs of an infected mouse model.29 A double knockout of two Brucella abortus sRNAs, abcR1 and abcR2, resulted in a significant decrease in intracellular survival following infection of murine macrophages and a mouse model of chronic B. abortus infection.30 These abcR sRNAs regulate metabolism genes, including amino acid and polyamine transport, and may play a role in targeting mRNA degradation. Depletion of the sRNA sX12 in the plant pathogen Xanthomonas campestris pv vesicatoria (Xcv) decreased disease symptoms in infected pepper plants. This effect was specifically rescued by ectopic expression of the sRNA.31 Similarly, a significant reduction in lesion diameter was observed in immature pears upon depletion of the sRNAs ryhA, and rprA from the plant pathogen Erwinia amylovora, a phenotype that can be subsequently rescued by expressing rhyA and rprA from plasmids.32 Finally, sRNAs were found to silence the avirulence gene Avr3a in the oomycete plant fungus Phytophthora sojae, leading to escape from host detection and increased virulence.33

Bacterial sRNA target identification

Although deep sequencing methods have steadily increased the number of candidate bacterial sRNAs, identification of specific mRNA targets modified by sRNAs remains a challenging task. A recent study reported experimental validation of direct mRNA targets for only ~50 sRNAs.34 The hybridization between sRNAs and their cognate targets are usually dependent on a core interaction of six to eight contiguous bases pairs. sRNAs are thought to hybridize to well-accessible regions such as hairpin loops or single strand sequences.35 Computational prediction of sRNA targets offers a screening tool to identify an initial pool of high quality candidates for follow-on experimental validation. A number of algorithms have been described for sRNA target prediction, including TargetRNA,36 sTarPicker,37 and other strategies.37,38 These methods utilize parameters such as prediction of Hfq binding sites, strength of sRNA-mRNA hybridization duplexes, sequence analysis at translation initiation sites, interaction site accessibility, and machine learning. However, all computational methods still suffer from a high false positive rate, but are expected to gradually improve as a mechanistic understanding of sRNA–mRNA target interactions becomes more refined.

Gene Regulation and Host Response by MicroRNAs in Eukaryotes

miRNA biogenesis and target recognition

Eukaryotic miRNAs are ~22–25 bp endogenous non-coding RNAs that function as post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression in a wide spectrum of biological processes, including oncogenesis, development, and host immune response.39 Unlike bacterial sRNAs, miRNAs are initially transcribed as primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs) several kilobases in length that contain embedded hairpin structures with stem regions and terminal loops.40,41 The hairpin structures are recognized and excised by the microprocessor complex in the nucleus, which consists of the RNase III-like enzyme Drosha and dsRNA binding protein DGCR8.42,43 The processed ~65–70 nucleotide hairpin structure, termed the precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA), is exported into the cytoplasm by Exportin-5,44,45 where the pre-miRNA is processed by another RNase III enzyme, Dicer, to yield the mature 22–25 nt duplex.46,47 The guide strand of the mature duplex is loaded into a multi-protein complex, RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC), to direct subsequent miRNA:mRNA target interaction and gene silencing. The catalytic component of RISC is the Argonaute (AGO) protein, which mediates binding and silencing of the target mRNAs.48 Almost every aspect of miRNA biogenesis, from transcription and processing to subcellular localization and stability, is highly regulated in a sequence- and cell-specific manner.

Given that there are over one thousand miRNAs in humans and each miRNA is thought to bind multiple targets, it is predicted that ~60% of the human transcriptome may be regulated by miRNAs.49 miRNAs downregulate translation by binding to the miRNA response elements (MREs) in the 3′ UTR (3′ untranslated region) of their mRNA targets to inhibit mRNA translation or stability.50 Complementarity between miRNAs and MREs can be near perfect in plants, but only partial in animals. One important finding is the so-called “seed rule”, in which extensive Watson–Crick base pairing between the “seed” region (2–7 nt from the 5′ end) of the miRNA and its target, remarkably reduces the number of false positive predictions.51,52 The seed rule has been widely applied as the fundamental criteria by most current prediction algorithms to screen for potential miRNA target genes. Nevertheless, considerable evidence exists to argue that the seed pairing is either not required or not sufficient for predicting miRNA:mRNA interactions.53 Other features within 3′ UTRs, in addition to seed pairing, have been demonstrated to be important determinants, including overall thermodynamic stability of the miRNA:mRNA duplex, total number of MREs within the 3′ UTR, accessibility of the MRE, position of the MRE related to the stop codon, and local AU rich elements.54-56 Thus, as is the case for bacterial sRNA targets, current computational target prediction is far from established, and predicted target candidates need to be experimentally verified.

miRNA function in bacterial infection

A variety of studies in cancer have strongly implicated miRNAs as potential biomarkers for distinguishing different types of cancer and progression of disease onset.57 Like cancer, the host produces miRNA signatures that act as complex fingerprints for immune response during pathogen infection. Host immunity must be tightly regulated in order to achieve pathogen clearance, but at the same time, avoid consequences of deregulated gene expression, such as septic shock or uncontrolled inflammation. An early example of miRNA response to pathogen infection was reported in plants, in which miR-393a expression in Arabidopsis thaliana mediates resistance against Pseudomonas syringae. During infection, the A. thaliana FLS2 receptor senses a P. syringae flagellin-derived peptide and induces miR-393a expression to modulate auxin signaling and plant immune defenses.58

miRNAs play a critical role in regulating both innate and adaptive immune responses against various pathogens. Two key host miRNAs, miR-146 and miR-155, were found to be strongly upregulated from a panel of ~200 miRNAs following stimulation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria and activator of innate immunity, in human monocytes.59 miR-146 has since been found to be upregulated in response to multiple pathogens, including Helicobacter pylori,60 Listeria monocytogenes,61 F. tularensis,62 and S. Typhimurium.63 miR-146 upregulation is dependent on NFκB, a key transcription factor that regulates practically all aspects of the innate immune response, including synthesis of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL-1β, and regulation of immune cell migration. Interestingly, TRAF6 (TNF receptor-associated factor 6) and IRAK1 (IL-1 receptor-associated kinase 1), two components of the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) signaling pathway that act upstream of NFκB, were found to be targets of miR-146a, suggesting that miR-146a functions in the negative feedback regulation of TLR signaling in order to ensure appropriate strength and duration of the innate immune response.59

miR-155 can be stimulated by both bacterial and viral antigens, including LPS,64-66 peptidoglycan through the intracellular NOD pathway,67 and nucleic acids, such as poly(I:C) and hypomethylated DNA.65 miR-155 has been shown to play a prominent role during infection by H. pylori, a gram-negative bacteria estimated to chronically infect the gastric mucosa of half the world population. Gastric mucosa samples from H. pylori-infected human and mouse systems were found to exhibit elevated levels of miR-155, and miR-155 knockout mice were incapable of controlling an H. pylori infection.68,69 miR-155 upregulation was shown to be dependent on the H. pylori virulence factors vacuolating toxin A and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, as well as LPS.70 In addition, other miRNAs, including miR-21, the miR-371–372–373 cluster, and miR-223 have been implicated in H. pylori infection.71,72 High levels of miR-223 in serum have also been found to be a reliable indicator of sepsis.73

miR-155 is proposed to fine tune inflammatory cytokine production through negative feedback loops by targeting TAB2,66 FADD (fas-associated death domain protein), IKKε (IκB kinase ε), and Ripk1 (receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1).64 miR-155-deficient dendritic cells exhibited impaired ability in antigen presentation and T cell activation, suggesting its involvement in bridging innate and adaptive immunity.74 Mice lacking miR-155 displayed loss of vaccine efficiency upon infection with S. Typhimurium,74 prolonged colonization of Citrobacter rodentium in the gastrointestinal tract,75 and deficient CD8+ T cell response to L. monocytogenes infection.76 miR-155 was shown to restrict Th2 but not Th1 lineage commitment after CD4+ T cell activation,74,77 and is also required for the differentiation and proliferation of regulatory T helper cells, which function to self-limit the immune response.78,79 Two subspecies of F. tularensis were shown to exhibit differential regulation of miR-155. miR-155 expression is strongly induced by the low virulence F. novocida, but remains mostly unchanged in the highly-virulent F. tularensis, suggesting that miR-155 may regulate this difference in pathogenicity.62

Other miRNAs have been shown to be downregulated in response to less pathogenic bacterial strains. miR-125b functions as a negative regulator of the TLR pathway in the absence of pathogen64 and directly targets TNF-α. In Mycobacterium, the non-pathogenic M. smegmatis induced low levels of miR-125b and high levels of TNF-α in human macrophages, whereas pathogenic M. tuberculosis activated high levels of miR-125b and low levels of TNF-α, indicating that miR-125b is a key regulator of the host inflammatory response during pathogen infection.80 Furthermore, patients with latent M. tuberculosis infection expressed lower levels of 17 different miRNAs in peripheral blood monocytes compared with patients with active M. tuberculosis infection. Several of the upregulated miRNAs, including miR-223 and miR-451, were implicated in hematopoetic differentiation and may thus play a role in granuloma formation.81

Finally, the highly conserved let-7 family has also been shown to be downregulated in response to infection by H. pylori,82 S. enterica,63 L. monocytogenes,83 and the protozoan Cryptosporidium parvum.84 A key target of let-7 is TLR4, the primary receptor that binds bacterial LPS to activate the host innate immune response. Repression of let-7 leads to upregulation of both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines to balance host immunity and prevent excessive inflammation. In contrast to bacterial infection, viruses have evolved to exploit this balance. Let-7 expression is upregulated in respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection, which results in a decrease in antiviral cytokine response.85

sRNAs in Viral Infection to Modulate Host Function

Viruses are dependent on the host for their own replication and use a variety of RNA-based mechanisms to manipulate host gene expression and function. For example, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) molecules are often produced as replication intermediates during viral infection. Depending on their nucleotide length, dsRNAs can induce host RNA interference (RNAi) or a type I interferon (IFN) response, resulting in restricted viral replication or host cell death, respectively.86-89 Many viruses produce proteins that exhibit RNA silencing suppressor (RSS) activity to facilitate adaptation to innate antiviral responses.90 The RSS proteins Tat, NS1, and VP35 in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), influenza A, and ebola virus, respectively, all feature RNA binding domains that block RNAi and the type I IFN response by binding to long (>30 nt) dsRNA, unprocessed and mature miRNAs, and siRNAs, to shield these reactive RNA species from the host dsRNA sensing proteins (RIG-I and MDA5) and the RNAi processing Dicer/TRBP/PACT complex.91-95

Human adenovirus (AdV), which causes upper respiratory infections, has evolved an alternative strategy to block the RNAi pathway via saturation of RISC with very abundant and highly structured virus-associated (VA) sRNAs, VA1 and VA2, produced as late virus transcripts. Some VA sRNAs have been suggested to act as miRNAs to suppress host mRNA translation.96 VA1 and VA2 are indispensable for AdV replication, since deletion of both regulatory elements leads to cessation of virus production.96 Primate cells infected with the γ-herpesvirus Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) express large amounts of two sRNAs, EBER1, and EBER2, which can functionally substitute for the VA sRNAs in the lytic growth of AdV serotype 5, although there is no sequence similarity between the VA and EBER sRNAs.97 These studies demonstrate that highly-structured viral RNAs like VA1/2 and EBER1/2 function as RSSs that competitively inhibit processing of host and virus dsRNAs by Dicer.

Another mechanism used to subvert the host is the expression of viral miRNA orthologs to manipulate host signaling pathways, first observed in EBV.98 Viral miRNAs have since been identified in many DNA viruses, including all three herpesvirus subfamilies, polyomavirus, adenovirus, and in a bovine leukemia retrovirus.99 For example, Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV), the causative agent of primary effusion lymphoma, encodes 12 miRNA genes. Viral miRNAs designated KSHV-miR-K11–12 were found to share 100% seed sequence similarity with miR-155, a host miRNA critical for host immune response to infection. The 3′UTR of the transcriptional repressor BACH-1 has been validated as a specific target of KSHV-miR-K11–12 and miR-155. In cells expressing both miRNAs, BACH-1 protein levels were decreased. Additionally, transcript expression profiling identified 66 genes that were commonly downregulated in cell lines stably expressing either KSHV-miR-K11–12 or miR-155, illustrating that viruses can highjack or mimic host regulatory factors to optimize the host environment for pathogen replication.100

HIV

The retrovirus HIV-1 also encodes siRNAs and miRNAs that restrict accumulation of viral cytotoxic proteins to ensure the prolonged host fitness necessary for successful completion of the virus replication cycle. The viral miRNAs originate from structured regions in the viral RNA genome, such as the RNA packaging signal that triggers Drosha/Dicer processing or antisense transcripts produced from 3′ UTRs. Suppression of viral siRNAs by antagomirs significantly stimulated virus production, thus validating their role in modulation of virus gene expression and possibly, establishment of HIV-1 latency. A specific HIV-1 siRNA was shown to play a dual role by targeting host tRNA during protein synthesis. Reverse transcription (RT) initiation of the HIV-1 genome requires specific host tRNAs, tRNALys3, and tRNALys5a, that serve as primers for HIV RT Polymerase. The levels of tRNALys were reduced by 95–99% in HIV-1 infected cells, which slows down host protein synthesis and metabolism, processes associated with establishment of persistent HIV-1 infection. This tRNALys reduction was found to stem from dsRNA formation between the HIV-1 primer binding site and host tRNA.101 Interestingly, miR-29a has also been shown to inhibit HIV-1 production by targeting the 3′ UTR and enhancing viral mRNA association with RISC and P bodies,102 illustrating that the host also employs sRNA-based strategies to defeat pathogen infection.

With the exception of the AdV VA1/2 and EBV EBER1/2 sRNAs, which can constitute up to 80% of total Dicer-associated sRNAs in lytic viruses,96 the majority of viral siRNAs represent less than 1% of the total pool of sRNAs in host cells. Recent deep sequencing analysis has led to the discovery of low abundance sRNAs in mammalian cells infected with dengue virus, vesicular stomatitis virus, polio virus, hepatitis C virus, and West Nile virus, thus opening new avenues for development of RNA-directed strategies aimed at containing viral infections.103

Influenza

The genomic 3′ and 5′ ends of the eight genome segments of influenza viruses have long been considered to have no role in virulence and were neglected in traditional Sanger-based sequencing. Recently, a deep sequencing approach was used to identify influenza A virus-derived small viral RNAs (svRNAs) produced in infected host cells.104 These svRNAs were found to be 22–27 nt in length and corresponded to the 5′ end of each of the viral genomic RNA segments. Synthesis of svRNAs required viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, nucleoprotein, and the nuclear export protein NS2. Depletion of svRNAs produced a significant loss of viral RNA in a segment-specific manner.

Influenza infection also induces host miRNA responses in a strain-specific manner. Eighteen miRNAs in the mouse transcriptome have been found to be differentially expressed in response to infection with the highly-virulent 1918 H1N1 influenza A virus compared with infection with a low pathogenicity H1N1 virus.105 Gene ontology analysis was used to identify several pathways that inversely correlated with pathogenicity, including miR-200a, a modulator of the JAK-STAT pathway that maintains the integrity of the lung epithelium, and miR-223, a negative modulator of neutrophil activation. This differential regulation of miRNA expression may contribute to differences in viral strain pathogenicity, and more specifically, to the extreme virulence of the 1918 H1N1 virus.

Other studies have found miRNAs that are common to multiple strains of influenza infection. One of the miRNAs thought to be involved in the influenza virus replication cycle is miR-146a, described earlier to be upregulated in response to LPS. Inhibition of miR-146a significantly increased viral propagation.106 Another host miRNA, miR-451, which regulates a subset of proinflammatory cytokine responses, is elevated in influenza-infected lung dendritic cells. Dendritic cells treated with RNA antagomirs directed against miR-451 secreted elevated levels of the cytokines IL-6, TNF, CCL5/RANTES, and CCL3/MIP1α107, suggesting that influenza infection has adapted to the host miRNA machinery by inducing a miRNA that negatively regulates dendritic cell cytokine production and the host immune response.

Viral sRNA mechanisms during plant infection

Viral pathogens are also targeted by the RNA silencing machinery in plants, leading to the accumulation of viral-derived siRNAs. These siRNAs constitute part of the antiviral defense mechanisms in plants. However, viruses can also hijack the plant RNA silencing machinery and express viral-derived siRNAs to target and downregulate host transcripts, contributing to infection. For example, the siRNA sRCC1 from cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) has been shown to promote cleavage of the Atlg76950 transcript during infection of Arabidopsis.108 A siRNA from CMV-Y satellite RNA mediates cleavage of CHLI transcript, leading to yellowing symptoms in infected tobacco plants by impairing chlorophyll biosynthesis pathway.109,110

Another category of infectious nucleic-based particles are viroids, single-stranded RNAs ranging from 250 to 400 nt that encode no protein product and can infect crops.111 Viroids fold into sophisticated RNA structures and manipulate host factors to replicate and travel inside the host plant.112-114 There are two viroid families: (1) Avsunviroidae, which has branched secondary structures and replicate in the chloroplasts, and (2) Pospiviroidae, with rod-like secondary structure and replication in the nucleus. Symptoms of viroid infection include growth stunting, leaf epinasty and deformation, fruit distortion, stem and leaf necrosis, and plant death. Recent studies suggest that viroids can generate siRNAs of 21–24 nt in the host that target and direct the cleavage of reporter genes or host genes in a sequence-specific manner.115 This post-transcriptional RNA silencing effect may be the underlying mechanism of viroid pathogenicity.

Conclusions

In the last decade, research in sRNA identification and functional analysis has begun to reveal a previously hidden regulatory layer in the already complex gene networks that control cellular function and behavior. As discussed in this review, sRNAs have been shown to act as regulators of pathogen virulence and host immunity, suggesting the possibility that inhibition of key sRNA folding or target mRNA interactions can be developed as the basis of novel anti-infective strategies.

Many fundamental questions on sRNA biology remain to be answered. For most sRNAs, the exact cellular function and downstream mRNA targets remain to be elucidated. Experimental efforts to determine cellular function of sRNAs are time-consuming and labor-intensive, while bioinformatics prediction of target mRNAs remains largely unreliable due to the imperfect complementarity between the sRNA and mRNA. Experimental strategies that utilize Hfq co-immunoprecipitation may improve the process by stabilizing sRNA:mRNA pairs for direct isolation of mRNA targets. Given their ~50–450 nt length, it is likely that bacterial sRNAs assume a defined secondary and tertiary structure containing stem/loop architecture. To examine sRNA structure, our team is currently using SHAPE (selective 2’-hydroxyl acylation analyzed by primer extension) to analyze the secondary structures of sRNAs identified from ultra high-throughput sequencing of Yersinia and Burkholderia pathogen transcriptomes. In SHAPE, the reactivity of the 2’-hydroxyl group in sRNAs is monitored by chemical mapping to measure the dynamics and solvent exposure of local RNA structure. Single-stranded or flexible RNA regions will have high 2’-hydroxyl reactivity, whereas RNA stem structures engaged in base pairing have lower reactivity. We expect this type of information will be invaluable for in vitro modeling studies with small molecules to analyze sRNA stability and identify potential chemical scaffolds or inhibitory RNAs that can bind and inhibit sRNA functions.

The potential development of new therapies for infectious disease using RNA-based strategies has attracted the attention of biotechnology entrepreneurs, especially in the siRNA arena. There have been a growing number of clinical trials based on siRNAs,116,117 which involve delivery of siRNAs to target tissues for treatment of such disorders as macular degeneration and various cancers. As with any novel strategy for drug development, there still remain technical challenges that need to be overcome, including minimization of off-target effects (OTE) and systemic delivery of siRNAs in the body. Nevertheless, the research momentum in sRNA identification and functional analysis represents promising high-value potential for translating fundamental bioscience discovery into therapeutic treatment. The overall promise of sRNAs as a powerful new approach to induce specific inhibition of gene expression has generated enormous enthusiasm and hope in the biomedical community that sRNA-based therapeutic treatment of disease can become a reality in the near future.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

The writing of this manuscript was supported by a LANL Laboratory-Directed Research and Development Directed Research Grant 20110051DR to E Hong-Geller.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/virulence/article/26119

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waters LS, Storz G. Regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Cell. 2009;136:615–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd DP, Li N, Micheva-Viteva SN, Munsky B, Hong-Geller E, Werner JH. Counting small RNA in pathogenic bacteria. Anal Chem. 2013;85:4938–43. doi: 10.1021/ac303792p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozomara A, Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: integrating microRNA annotation and deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D152–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffiths-Jones S, Grocock RJ, van Dongen S, Bateman A, Enright AJ. miRBase: microRNA sequences, targets and gene nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34(Database issue):D140–4. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths-Jones S. miRBase: the microRNA sequence database. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;342:129–38. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-123-1:129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, van Dongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Database issue):D154–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Griffin BE. Separation of 32P-labelled ribonucleic acid components. The use of polyethylenimine-cellulose (TLC) as a second dimension in separating oligoribonucleotides of ‘4.5 S’ and 5 S from E. coli. FEBS Lett. 1971;15:165–8. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(71)80304-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Altuvia S. Identification of bacterial small non-coding RNAs: experimental approaches. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2007;10:257–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sittka A, Lucchini S, Papenfort K, Sharma CM, Rolle K, Binnewies TT, Hinton JC, Vogel J. Deep sequencing analysis of small noncoding RNA and mRNA targets of the global post-transcriptional regulator, Hfq. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000163. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoder-Himes DR, Chain PS, Zhu Y, Wurtzel O, Rubin EM, Tiedje JM, Sorek R. Mapping the Burkholderia cenocepacia niche response via high-throughput sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3976–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813403106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sridhar J, Gunasekaran P. Computational small RNA prediction in bacteria. Bioinform Biol Insights. 2013;7:83–95. doi: 10.4137/BBI.S11213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Washietl S, Hofacker IL, Stadler PF. Fast and reliable prediction of noncoding RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2454–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409169102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Møller T, Franch T, Højrup P, Keene DR, Bächinger HP, Brennan RG, Valentin-Hansen P. Hfq: a bacterial Sm-like protein that mediates RNA-RNA interaction. Mol Cell. 2002;9:23–30. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos CG, Sousa SA, Grilo AM, Feliciano JR, Leitão JH. The second RNA chaperone, Hfq2, is also required for survival under stress and full virulence of Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:1515–26. doi: 10.1128/JB.01375-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Geng J, Song Y, Yang L, Feng Y, Qiu Y, Li G, Guo J, Bi Y, Qu Y, Wang W, et al. Involvement of the post-transcriptional regulator Hfq in Yersinia pestis virulence. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson GT, Roop RM., Jr. The Brucella abortus host factor I (HF-I) protein contributes to stress resistance during stationary phase and is a major determinant of virulence in mice. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:690–700. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meibom KL, Forslund AL, Kuoppa K, Alkhuder K, Dubail I, Dupuis M, Forsberg A, Charbit A. Hfq, a novel pleiotropic regulator of virulence-associated genes in Francisella tularensis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1866–80. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01496-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christiansen JK, Larsen MH, Ingmer H, Søgaard-Andersen L, Kallipolitis BH. The RNA-binding protein Hfq of Listeria monocytogenes: role in stress tolerance and virulence. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3355–62. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.11.3355-3362.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bohn C, Rigoulay C, Bouloc P. No detectable effect of RNA-binding protein Hfq absence in Staphylococcus aureus. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koo JT, Alleyne TM, Schiano CA, Jafari N, Lathem WW. Global discovery of small RNAs in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis identifies Yersinia-specific small, noncoding RNAs required for virulence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E709–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101655108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beauregard A, Smith EA, Petrone BL, Singh N, Karch C, McDonough KA, Wade JT. Identification and characterization of small RNAs in Yersinia pestis. RNA Biol. 2013;10:10. doi: 10.4161/rna.23590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qu Y, Bi L, Ji X, Deng Z, Zhang H, Yan Y, Wang M, Li A, Huang X, Yang R, et al. Identification by cDNA cloning of abundant sRNAs in a human-avirulent Yersinia pestis strain grown under five different growth conditions. Future Microbiol. 2012;7:535–47. doi: 10.2217/fmb.12.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li GW, Chen H, Babu M, Hearn J, Emili A, Xie XS. Quantifying E. coli proteome and transcriptome with single-molecule sensitivity in single cells. Science. 2010;329:533–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1188308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McArthur SD, Pulvermacher SC, Stauffer GV. The Yersinia pestis gcvB gene encodes two small regulatory RNA molecules. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wadler CS, Vanderpool CK. Characterization of homologs of the small RNA SgrS reveals diversity in function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:5477–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heroven AK, Böhme K, Rohde M, Dersch P. A Csr-type regulatory system, including small non-coding RNAs, regulates the global virulence regulator RovA of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis through RovM. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:1179–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mann B, van Opijnen T, Wang J, Obert C, Wang YD, Carter R, McGoldrick DJ, Ridout G, Camilli A, Tuomanen EI, et al. Control of virulence by small RNAs in Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002788. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Postic G, Dubail I, Frapy E, Dupuis M, Dieppedale J, Charbit A, Meibom KL. Identification of a novel small RNA modulating Francisella tularensis pathogenicity. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41999. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caswell CC, Gaines JM, Ciborowski P, Smith D, Borchers CH, Roux CM, Sayood K, Dunman PM, Roop Ii RM. Identification of two small regulatory RNAs linked to virulence in Brucella abortus 2308. Mol Microbiol. 2012;85:345–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidtke C, Findeiss S, Sharma CM, Kuhfuss J, Hoffmann S, Vogel J, Stadler PF, Bonas U. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of the plant pathogen Xanthomonas identifies sRNAs with putative virulence functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:2020–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng Q, McNally RR, Sundin GW. Global small RNA chaperone Hfq and regulatory small RNAs are important virulence regulators in Erwinia amylovora. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:1706–17. doi: 10.1128/JB.02056-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qutob D, Chapman BP, Gijzen M. Transgenerational gene silencing causes gain of virulence in a plant pathogen. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1349. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao Y, Wu J, Liu Q, Zhao Y, Ying X, Cha L, Wang L, Li W. sRNATarBase: a comprehensive database of bacterial sRNA targets verified by experiments. RNA. 2010;16:2051–7. doi: 10.1261/rna.2193110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Storz G, Vogel J, Wassarman KM. Regulation by small RNAs in bacteria: expanding frontiers. Mol Cell. 2011;43:880–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tjaden B. TargetRNA: a tool for predicting targets of small RNA action in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W109-13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ying X, Cao Y, Wu J, Liu Q, Cha L, Li W. sTarPicker: a method for efficient prediction of bacterial sRNA targets based on a two-step model for hybridization. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang Y, Sun S, Wu T, Wang J, Liu C, Chen L, Zhu X, Zhao Y, Zhang Z, Shi B, et al. Identifying Hfq-binding small RNA targets in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:950–5. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.02.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong-Geller E, Li N. microRNAs as therapeutic targets to combat diverse human diseases. In: Rundfeldt C, editor. Drug Development-A Case Study Based Insight into Modern Strategies: Intech; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cai X, Hagedorn CH, Cullen BR. Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. RNA. 2004;10:1957–66. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, Lee J, Provost P, Rådmark O, Kim S, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Landthaler M, Yalcin A, Tuschl T. The human DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 and Its D. melanogaster homolog are required for miRNA biogenesis. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee Y, Jeon K, Lee JT, Kim S, Kim VN. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2002;21:4663–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3011–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hutvágner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Bálint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ketting RF, Fischer SE, Bernstein E, Sijen T, Hannon GJ, Plasterk RH. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2654–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.927801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pillai RS, Artus CG, Filipowicz W. Tethering of human Ago proteins to mRNA mimics the miRNA-mediated repression of protein synthesis. RNA. 2004;10:1518–25. doi: 10.1261/rna.7131604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman RC, Farh KK, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:102–14. doi: 10.1038/nrg2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115:787–98. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, Bartel DP, Linsley PS, Johnson JM. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–73. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Didiano D, Hobert O. Perfect seed pairing is not a generally reliable predictor for miRNA-target interactions. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:849–51. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li N, Flynt AS, Kim HR, Solnica-Krezel L, Patton JG. Dispatched Homolog 2 is targeted by miR-214 through a combination of three weak microRNA recognition sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4277–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hon LS, Zhang Z. The roles of binding site arrangement and combinatorial targeting in microRNA repression of gene expression. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R166. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kertesz M, Iovino N, Unnerstall U, Gaul U, Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1278–84. doi: 10.1038/ng2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Di Leva G, Croce CM. miRNA profiling of cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2013;23:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Navarro L, Dunoyer P, Jay F, Arnold B, Dharmasiri N, Estelle M, Voinnet O, Jones JD. A plant miRNA contributes to antibacterial resistance by repressing auxin signaling. Science. 2006;312:436–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1126088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12481–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Petrocca F, Visone R, Onelli MR, Shah MH, Nicoloso MS, de Martino I, Iliopoulos D, Pilozzi E, Liu CG, Negrini M, et al. E2F1-regulated microRNAs impair TGFbeta-dependent cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in gastric cancer. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:272–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schnitger AK, Machova A, Mueller RU, Androulidaki A, Schermer B, Pasparakis M, Krönke M, Papadopoulou N. Listeria monocytogenes infection in macrophages induces vacuolar-dependent host miRNA response. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cremer TJ, Ravneberg DH, Clay CD, Piper-Hunter MG, Marsh CB, Elton TS, Gunn JS, Amer A, Kanneganti TD, Schlesinger LS, et al. MiR-155 induction by F. novicida but not the virulent F. tularensis results in SHIP down-regulation and enhanced pro-inflammatory cytokine response. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8508. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schulte LN, Eulalio A, Mollenkopf HJ, Reinhardt R, Vogel J. Analysis of the host microRNA response to Salmonella uncovers the control of major cytokines by the let-7 family. EMBO J. 2011;30:1977–89. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tili E, Michaille JJ, Cimino A, Costinean S, Dumitru CD, Adair B, Fabbri M, Alder H, Liu CG, Calin GA, et al. Modulation of miR-155 and miR-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/TNF-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol. 2007;179:5082–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O’Connell RM, Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Cheng G, Baltimore D. MicroRNA-155 is induced during the macrophage inflammatory response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:1604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610731104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ceppi M, Pereira PM, Dunand-Sauthier I, Barras E, Reith W, Santos MA, Pierre P. MicroRNA-155 modulates the interleukin-1 signaling pathway in activated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2735–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811073106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schulte LN, Westermann AJ, Vogel J. Differential activation and functional specialization of miR-146 and miR-155 in innate immune sensing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:542–53. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiao B, Liu Z, Li BS, Tang B, Li W, Guo G, Shi Y, Wang F, Wu Y, Tong WD, et al. Induction of microRNA-155 during Helicobacter pylori infection and its negative regulatory role in the inflammatory response. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:916–25. doi: 10.1086/605443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Oertli M, Engler DB, Kohler E, Koch M, Meyer TF, Müller A. MicroRNA-155 is essential for the T cell-mediated control of Helicobacter pylori infection and for the induction of chronic Gastritis and Colitis. J Immunol. 2011;187:3578–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fassi Fehri L, Koch M, Belogolova E, Khalil H, Bolz C, Kalali B, Mollenkopf HJ, Beigier-Bompadre M, Karlas A, Schneider T, et al. Helicobacter pylori induces miR-155 in T cells in a cAMP-Foxp3-dependent manner. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9500. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Belair C, Baud J, Chabas S, Sharma CM, Vogel J, Staedel C, Darfeuille F. Helicobacter pylori interferes with an embryonic stem cell micro RNA cluster to block cell cycle progression. Silence. 2011;2:7. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-2-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Z, Li Z, Gao C, Chen P, Chen J, Liu W, Xiao S, Lu H. miR-21 plays a pivotal role in gastric cancer pathogenesis and progression. Lab Invest. 2008;88:1358–66. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2008.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang H, Zhang P, Chen W, Feng D, Jia Y, Xie L. Serum microRNA signatures identified by Solexa sequencing predict sepsis patients’ mortality: a prospective observational study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38885. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rodriguez A, Vigorito E, Clare S, Warren MV, Couttet P, Soond DR, van Dongen S, Grocock RJ, Das PP, Miska EA, et al. Requirement of bic/microRNA-155 for normal immune function. Science. 2007;316:608–11. doi: 10.1126/science.1139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clare S, John V, Walker AW, Hill JL, Abreu-Goodger C, Hale C, Goulding D, Lawley TD, Mastroeni P, Frankel G, et al. Enhanced susceptibility to Citrobacter rodentium infection in microRNA-155-deficient mice. Infect Immun. 2013;81:723–32. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00969-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lind EF, Elford AR, Ohashi PS. Micro-RNA 155 is required for optimal CD8+ T cell responses to acute viral and intracellular bacterial challenges. J Immunol. 2013;190:1210–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thai TH, Calado DP, Casola S, Ansel KM, Xiao C, Xue Y, Murphy A, Frendewey D, Valenzuela D, Kutok JL, et al. Regulation of the germinal center response by microRNA-155. Science. 2007;316:604–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1141229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lu LF, Thai TH, Calado DP, Chaudhry A, Kubo M, Tanaka K, Loeb GB, Lee H, Yoshimura A, Rajewsky K, et al. Foxp3-dependent microRNA155 confers competitive fitness to regulatory T cells by targeting SOCS1 protein. Immunity. 2009;30:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kohlhaas S, Garden OA, Scudamore C, Turner M, Okkenhaug K, Vigorito E. Cutting edge: the Foxp3 target miR-155 contributes to the development of regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;182:2578–82. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rajaram MV, Ni B, Morris JD, Brooks MN, Carlson TK, Bakthavachalu B, Schoenberg DR, Torrelles JB, Schlesinger LS. Mycobacterium tuberculosis lipomannan blocks TNF biosynthesis by regulating macrophage MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) and microRNA miR-125b. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:17408–13. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112660108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang C, Yang S, Sun G, Tang X, Lu S, Neyrolles O, Gao Q. Comparative miRNA expression profiles in individuals with latent and active tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Matsushima K, Isomoto H, Inoue N, Nakayama T, Hayashi T, Nakayama M, Nakao K, Hirayama T, Kohno S. MicroRNA signatures in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric mucosa. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:361–70. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Izar B, Mannala GK, Mraheil MA, Chakraborty T, Hain T. microRNA Response to Listeria monocytogenes Infection in Epithelial Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:1173–85. doi: 10.3390/ijms13011173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chen XM, Splinter PL, O’Hara SP, LaRusso NF. A cellular micro-RNA, let-7i, regulates Toll-like receptor 4 expression and contributes to cholangiocyte immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28929–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702633200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bakre A, Mitchell P, Coleman JK, Jones LP, Saavedra G, Teng M, Tompkins SM, Tripp RA. Respiratory syncytial virus modifies microRNAs regulating host genes that affect virus replication. J Gen Virol. 2012;93:2346–56. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044255-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kawai T, Akira S. Innate immune recognition of viral infection. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:131–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lecellier CH, Dunoyer P, Arar K, Lehmann-Che J, Eyquem S, Himber C, Saïb A, Voinnet O. A cellular microRNA mediates antiviral defense in human cells. Science. 2005;308:557–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1108784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pedersen IM, Cheng G, Wieland S, Volinia S, Croce CM, Chisari FV, David M. Interferon modulation of cellular microRNAs as an antiviral mechanism. Nature. 2007;449:919–22. doi: 10.1038/nature06205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilkins C, Dishongh R, Moore SC, Whitt MA, Chow M, Machaca K. RNA interference is an antiviral defence mechanism in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;436:1044–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.de Vries W, Berkhout B. RNAi suppressors encoded by pathogenic human viruses. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2007–12. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bennasser Y, Jeang KT. HIV-1 Tat interaction with Dicer: requirement for RNA. Retrovirology. 2006;3:95. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-3-95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bucher E, Hemmes H, de Haan P, Goldbach R, Prins M. The influenza A virus NS1 protein binds small interfering RNAs and suppresses RNA silencing in plants. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:983–91. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19734-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Haasnoot J, de Vries W, Geutjes EJ, Prins M, de Haan P, Berkhout B. The Ebola virus VP35 protein is a suppressor of RNA silencing. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e86. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li WX, Li H, Lu R, Li F, Dus M, Atkinson P, Brydon EW, Johnson KL, García-Sastre A, Ball LA, et al. Interferon antagonist proteins of influenza and vaccinia viruses are suppressors of RNA silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1350–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308308100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Richt JA, Lekcharoensuk P, Lager KM, Vincent AL, Loiacono CM, Janke BH, Wu WH, Yoon KJ, Webby RJ, Solórzano A, et al. Vaccination of pigs against swine influenza viruses by using an NS1-truncated modified live-virus vaccine. J Virol. 2006;80:11009–18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00787-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Andersson MG, Haasnoot PC, Xu N, Berenjian S, Berkhout B, Akusjärvi G. Suppression of RNA interference by adenovirus virus-associated RNA. J Virol. 2005;79:9556–65. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9556-9565.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bhat RA, Thimmappaya B. Two small RNAs encoded by Epstein-Barr virus can functionally substitute for the virus-associated RNAs in the lytic growth of adenovirus 5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983;80:4789–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pfeffer S, Zavolan M, Grässer FA, Chien M, Russo JJ, Ju J, John B, Enright AJ, Marks D, Sander C, et al. Identification of virus-encoded microRNAs. Science. 2004;304:734–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1096781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kincaid RP, Burke JM, Sullivan CS. RNA virus microRNA that mimics a B-cell oncomiR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3077–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116107109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Skalsky RL, Samols MA, Plaisance KB, Boss IW, Riva A, Lopez MC, Baker HV, Renne R. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus encodes an ortholog of miR-155. J Virol. 2007;81:12836–45. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01804-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schopman NC, Willemsen M, Liu YP, Bradley T, van Kampen A, Baas F, Berkhout B, Haasnoot J. Deep sequencing of virus-infected cells reveals HIV-encoded small RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:414–27. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nathans R, Chu CY, Serquina AK, Lu CC, Cao H, Rana TM. Cellular microRNA and P bodies modulate host-HIV-1 interactions. Mol Cell. 2009;34:696–709. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Parameswaran P, Sklan E, Wilkins C, Burgon T, Samuel MA, Lu R, Ansel KM, Heissmeyer V, Einav S, Jackson W, et al. Six RNA viruses and forty-one hosts: viral small RNAs and modulation of small RNA repertoires in vertebrate and invertebrate systems. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000764. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Perez JT, Varble A, Sachidanandam R, Zlatev I, Manoharan M, García-Sastre A, tenOever BR. Influenza A virus-generated small RNAs regulate the switch from transcription to replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11525–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001984107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Li Y, Chan EY, Li J, Ni C, Peng X, Rosenzweig E, Tumpey TM, Katze MG. MicroRNA expression and virulence in pandemic influenza virus-infected mice. J Virol. 2010;84:3023–32. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02203-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Terrier O, Textoris J, Carron C, Marcel V, Bourdon JC, Rosa-Calatrava M. Host microRNA molecular signatures associated with human H1N1 and H3N2 influenza A viruses reveal an unanticipated antiviral activity for miR-146a. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:985–95. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.049528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Rosenberger CM, Podyminogin RL, Navarro G, Zhao GW, Askovich PS, Weiss MJ, Aderem A. miR-451 regulates dendritic cell cytokine responses to influenza infection. J Immunol. 2012;189:5965–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Moissiard G, Voinnet O. RNA silencing of host transcripts by cauliflower mosaic virus requires coordinated action of the four Arabidopsis Dicer-like proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19593–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604627103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 109.Smith NA, Eamens AL, Wang MB. Viral small interfering RNAs target host genes to mediate disease symptoms in plants. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002022. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shimura H, Pantaleo V, Ishihara T, Myojo N, Inaba J, Sueda K, Burgyán J, Masuta C. A viral satellite RNA induces yellow symptoms on tobacco by targeting a gene involved in chlorophyll biosynthesis using the RNA silencing machinery. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002021. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ding B. The biology of viroid-host interactions. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2009;47:105–31. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schnell RJ, Olano CT, Kuhn DN. Detection of avocado sunblotch viroid variants using fluorescent single-strand conformation polymorphism analysis. Electrophoresis. 2001;22:427–32. doi: 10.1002/1522-2683(200102)22:3<427::AID-ELPS427>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Qi Y, Ding B. Inhibition of cell growth and shoot development by a specific nucleotide sequence in a noncoding viroid RNA. Plant Cell. 2003;15:1360–74. doi: 10.1105/tpc.011585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Schnölzer M, Haas B, Raam K, Hofmann H, Sänger HL. Correlation between structure and pathogenicity of potato spindle tuber viroid (PSTV) EMBO J. 1985;4:2181–90. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03913.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Itaya A, Zhong X, Bundschuh R, Qi Y, Wang Y, Takeda R, Harris AR, Molina C, Nelson RS, Ding B. A structured viroid RNA serves as a substrate for dicer-like cleavage to produce biologically active small RNAs but is resistant to RNA-induced silencing complex-mediated degradation. J Virol. 2007;81:2980–94. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02339-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Vaishnaw AK, Gollob J, Gamba-Vitalo C, Hutabarat R, Sah D, Meyers R, de Fougerolles T, Maraganore J. A status report on RNAi therapeutics. Silence. 2010;1:14. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-1-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Davidson BL, McCray PB., Jr. Current prospects for RNA interference-based therapies. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12:329–40. doi: 10.1038/nrg2968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]