Abstract

Non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src is a master regulator of cell proliferation. Hyperactive Src is a potent oncogene and a driver of cellular transformation and carcinogenesis. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2) is a tumor suppressor mediating growth suppression and apoptosis upon genotoxic stress through phosphorylation of p53 at Ser46. Here we show that Src phosphorylates HIPK2 and changes its subcellular localization. Using mass spectrometry we identified 9 Src-mediated Tyr-phosphorylation sites within HIPK2, 5 of them positioned in the kinase domain. By means of a phosphorylation-specific antibody we confirm that Src mediates phosphorylation of HIPK2 at Tyr354. We demonstrate that ectopic expression of Src increases the half-life of HIPK2 by interfering with Siah-1-mediated HIPK2 degradation. Moreover, we find that hyperactive Src binds HIPK2 and redistributes HIPK2 from the cell nucleus to the cytoplasm, where both kinases partially colocalize. Accordingly, we find that hyperactive Src decreases chemotherapeutic drug-induced p53 Ser46 phosphorylation and apoptosis activation. Together, our results suggest that Src kinase suppresses the apoptotic p53 pathway by phosphorylating HIPK2 and relocalizing the kinase to the cytoplasm.

Keywords: Src, HIPK2, p53, chemotherapeutic drug, apoptosis

Introduction

The non-receptor tyrosine kinase cellular Src (c-Src; in the following referred to as Src) plays a fundamental role in the regulation of cell proliferation.1 Src is activated in response to numerous growth-stimulating signals, including activation of growth factor receptors such as EGF receptor.2

Src kinase is a well-established proto-oncogene, and its constitutive activation has been linked to cellular transformation, migration, and invasion.3 Src activity is elevated in numerous cancer cells, and increased Src activity has been linked to the development of cancer including carcinomas of the colon, breast, lung, and ovary.3 Increased activity of c-Src correlates with poor clinical prognosis and resistance to cancer therapy.4,5

At the molecular level, Src activity is largely regulated by posttranslational modifications. Autophosphorylation of Src at Y416 is a prerequisite for activation of its kinase activity, and phosphorylation of Y527 by the kinase Csk promotes the intramolecular binding of the C-terminal region to its SH2 domain, which renders the kinase inactive.6,7 Accordingly, mutation of Y527 to phenylalanine results in an active, oncogenic Src protein.6 The viral form of the protein (v-Src) lacks this regulatory tyrosine residue due to truncation of the C terminus and thereby exhibits constitutive kinase activity.1

Homeodomain interacting kinase 2 (HIPK2) is a multifunctional signaling molecule and tumor suppressor mediating growth-regulatory and apoptotic cellular responses.8 The kinase is involved in numerous signaling pathways, including Wnt signaling, hypoxic response, and DNA damage response.9-11 Among those, the best-studied function is its role in DNA damage-activated signaling. In response to UV, ionizing radiation or chemotherapeutic drug treatment HIPK2 is activated through the checkpoint kinases ATM and ATR, which mediate HIPK2 stabilization through protecting HIPK2 from polyubiquitination by the ubiquitin ligase Siah-1.12-14 Furthermore, activation of HIPK2 requires autophosphorylation at Thr880/Ser882 to activate its kinase function. Moreover, phosphorylation at Thr880/Ser882 serves as a binding signal for the cis/trans isomerase Pin1, which couples HIPK2 activation to its stabilization by changing HIPK2 conformation.15 After lethal DNA damage, HIPK2 site-specifically phosphorylates the tumor suppressor protein p53 at Serine residue 46 and thereby activates the expression of pro-apoptotic p53 target genes.16,17 The growth-suppressive and apoptotic activity of HIPK2 has been tightly linked to its localization to the cell nucleus, in particular to its association with promyelocytic leukemia (PML) nuclear bodies (NBs).18-20 It has been previously described that HIPK2 is not exclusively distributed to the cell nucleus but can also localize to the cytoplasm.21-23 However, little is known about the cellular pathways and mechanisms that modulate HIPK2 localization.

Here we report that HIPK2 is regulated by the tyrosine kinase Src. Using mass spectrometry and phosphorylation-specific antibodies, we demonstrate that Src phosphorylates HIPK2 at multiple Tyr residues. We find that Src expression triggers stabilization of HIPK2 protein by interference with Siah-1-mediated HIPK2 degradation. Intriguingly, Src redistributes HIPK2 from the cell nucleus to the cytoplasm, where both kinases partially colocalize. Finally, we demonstrate that Src inhibits DNA damage-stimulated p53 phosphorylation at Ser46. Our findings identify a novel mechanism of HIPK2 regulation through tyrosine phosphorylation, and suggest that Src regulates HIPK2 function by regulating its subcellular localization.

Results

Src phosphorylates HIPK2 at Tyrosine residues

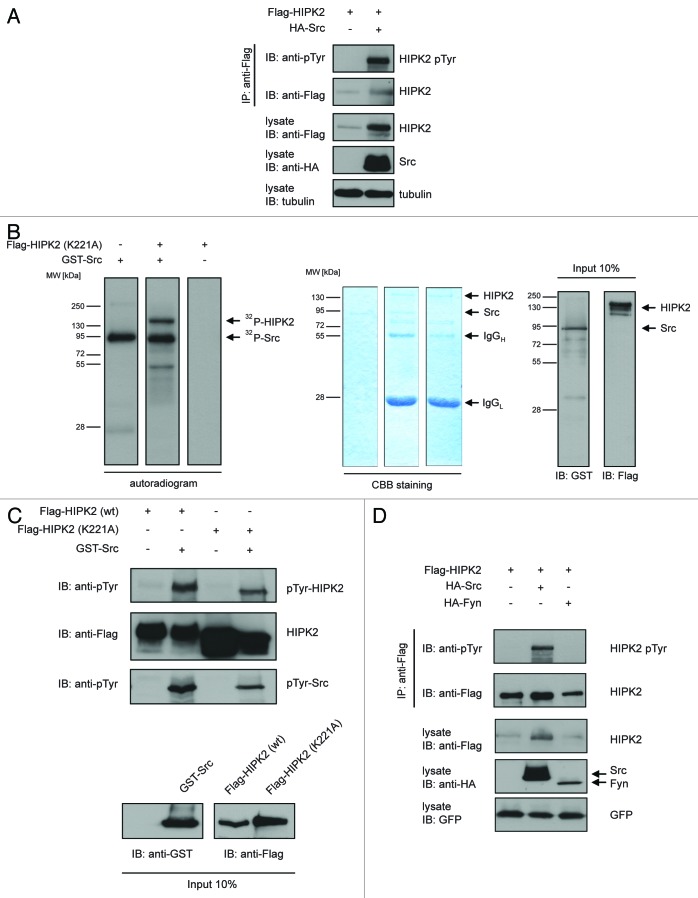

To assess whether HIPK2 is tyrosine phosphorylated by the proto-oncogenic tyrosine kinase Src, we expressed Flag-tagged HIPK2 in the presence and absence of Src, immunoprecipitated HIPK2, and analyzed its Tyr-phosphorylation (pTyr) by immunoblotting using a phospho-Tyrosine-specific antibody. Upon coexpression of Src, HIPK2 was strongly recognized by the pTyr antibody (Fig. 1A). This result suggests that Src phosphorylates HIPK2 at Tyr residues.

Figure 1. Src phosphorylates HIPK2 at Tyrosine residues (A) Ectopic expression of HA-Src mediates Tyr-phosphorylation of HIPK2. Flag-HIPK2 and HA-Src were expressed in 293T cells. Flag-HIPK2 was precipitated from lysates and Tyr-phosphorylation was analyzed using anti-phospho-Tyr (4G10) antibody. (B) Src phosphorylates HIPK2 in vitro. Flag-HIPK2 kinase-dead (K221A) was expressed in 293T cells and precipitated from lysates. In vitro kinase assay was performed using recombinant GST-Src and phosphorylation was examined by autoradiography. HIPK2 and Src input was analyzed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining and immunoblotting. (C) HIPK2 is phosphorylated by Src but not by the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Fyn. Flag-HIPK2 was expressed together with HA-Src or HA-Fyn in 293T cells. Flag-HIPK2 was precipitated from lysates, and Tyr-phosphorylation was analyzed using anti-phospho-Tyr (4G10) antibody.

To further substantiate our finding, we performed radioactive in vitro kinase assays. To this end, we used 32P-labeled γ-ATP as phosphate-donor along with bacterially expressed recombinant GST-Src and a kinase-dead HIPK2 mutant, HIPK2K221A, as a substrate for Src. Autoradiography revealed that Src mediates phosphorylation of HIPK2K221A (Fig. 1B). No phosphorylation of HIPK2 was detected in absence of recombinant Src. Furthermore, immunoblotting with a phospho-Tyr-specific antibody indicated that Src kinase phosphorylates HIPK2 at Tyr residues in vitro (Fig. 1C). Together, these data indicate that Src kinase directly phosphorylates HIPK2 in vitro.

We next aimed to determine whether Tyr-phosphorylation of HIPK2 might be specifically mediated by Src or could be also mediated by Fyn, another non-receptor tyrosine kinase family member. Expression of Fyn failed to induce Tyr-phosphorylation of HIPK2, while Src expression resulted in clear Tyr-phosphorylation of HIPK2 (Fig. 1D). This finding suggests that HIPK2 is not a general target of non-receptor tyrosine kinases. Taken together, these results indicate that HIPK2 is phosphorylated by Src kinase at Tyr residues.

Mapping of the Src phosphorylation sites on HIPK2 by mass spectrometry

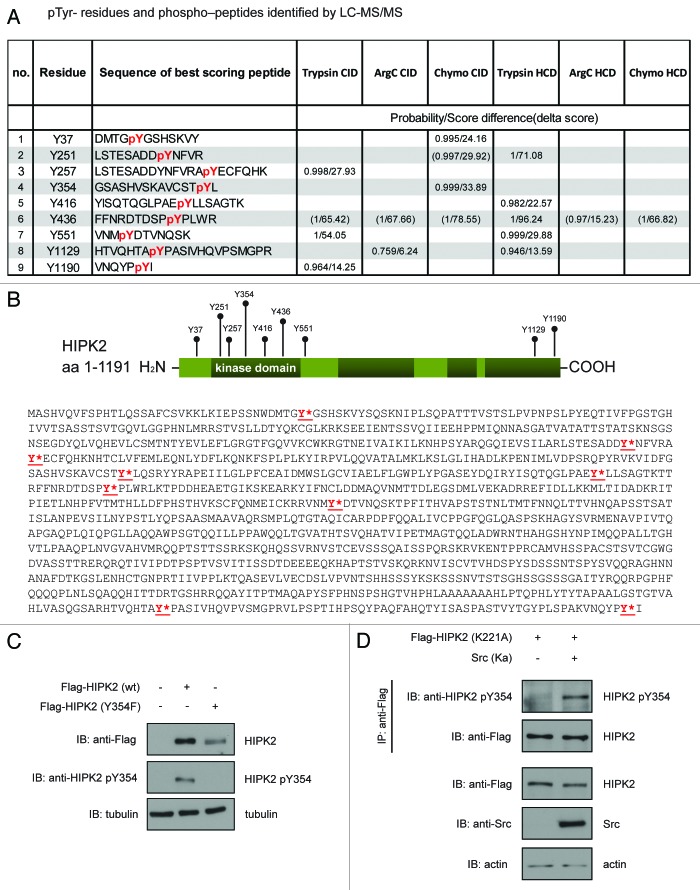

To identify the Tyr residues on HIPK2 phosphorylated by Src, we coexpressed Flag-HIPK2 and Src, immunoprecipitated HIPK2 and eluted Flag-HIPK2 with a Flag-peptide from the antibodies. Subsequently, we determined the Tyr-phosphorylation pattern of HIPK2 peptides generated by digestion with Trypsin, Chymotrypsin, or ArgC by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). Our LC-MS/MS analyses identified 9 phosphorylated Tyr residues in HIPK2 and achieved an overall coverage of more than 70% of all Tyr residues of the HIPK2 protein (Fig. 2A). Of note, the kinase domain of HIPK2, which is located between amino acids 189 and 520, appears to be a main target of tyrosine phosphorylation by Src, since 5 phospho-Tyr sites (Tyr251, 257, 354, 416, 436) are located within this domain (Fig. 2A and B).

Figure 2. Mass spectrometry identified numerous Tyr-phosphorylation sites upon Src expression on HIPK2. (A) Phosphotyrosine residues and phospho-peptides identified by LC‐MS/MS. (B) Schematic representation of the distribution of phosphorylated sites on wild-type Flag-HIPK2 purified from 293T cells. The sites found phosphorylated on Tyr are indicated. (C) Validation of anti-phospho-Tyr354 HIPK2 antibody. Flag-HIPK2 or Flag-HIPK2 (Y354F) mutant were expressed in H1299 cells, and lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using a phosphospecific phospho-Tyr354 HIPK2 antibody. (D) Src induces pTyr354 phosphorylation on HIPK2. Flag-HIPK2 kinase-dead mutant (K221A) was expressed in H1299 cells. Flag-HIPK2 (K221A) was precipitated from lysates and phosphorylation was analyzed using phospho-Tyr354 HIPK2 antibody.

Interestingly, Tyr354 located in the activation loop (T loop) of the HIPK2 kinase domain, was among the Src target sites (Fig. 2A and B). Tyr354 has been previously implicated in the regulation of HIPK2 kinase activity.22,23 This motivated us to raise a phosphorylation-specific antibody against this pTyr354 of HIPK2. We first assessed the specificity of the pTyr354 antibody. While the pTyr354 HIPK2 antibody failed to recognize a HIPK2 mutant harboring a mutated Tyr354, HIPK2Y354F, it clearly recognized the wild-type HIPK2 protein expressed in cells (Fig. 2C). Of note, wild-type HIPK2 has recently been shown to be autophosphorylated in cis at Tyr354 using mass spectrometry.22,23 To determine whether Src can mediate phosphorylation of Tyr354 in trans, we used kinase-dead HIPK2K221A, which lacks autophosphorylating activity, as a substrate for Src and analyzed its phosphorylation at Tyr354 using our phospho-specific pTyr354 HIPK2 antibody. Indeed, immunoblotting revealed that expression of kinase-active Src mediates phosphorylation of HIPK2K221A at Tyr354 (Fig. 2D). Taken together, these results indicate that Src phosphorylates HIPK2 at numerous Tyr residues, including Tyr354.

Src regulates HIPK2 stability

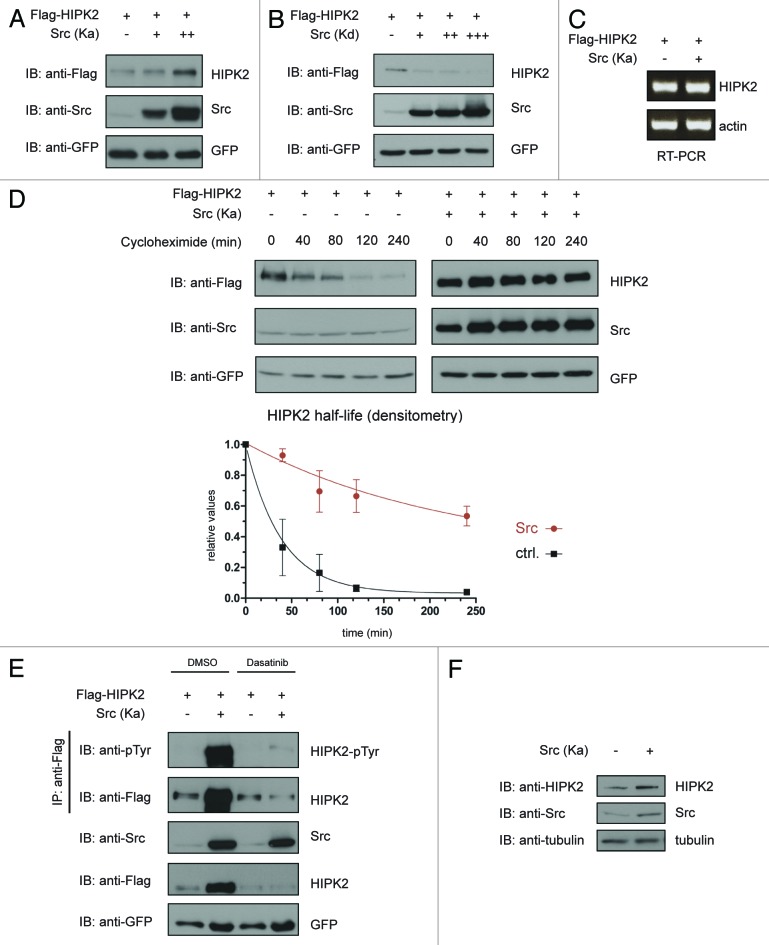

HIPK2 is known to be mainly regulated at the level of its protein stability.13,14,21 When we coexpressed kinase-activated Src with constant amounts of a HIPK2 expression construct, we recognized an increase in HIPK2 protein levels (Fig. 3A). In addition, expression of kinase-dead Src resulted in decreased HIPK2 protein levels (Fig. 3B). No change in the HIPK2 mRNA levels was observed (Fig. 3C), suggesting that Src regulates HIPK2 protein stability.

Figure 3. Src regulates HIPK2 stability. (A) Ectopically expressed Src leads to HIPK2 accumulation. 293T cells were transfected with Flag-HIPK2 together with increasing amounts of kinase-active Src (Y527F), and total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. (B) Ectopically expressed kinase-dead Src destabilizes HIPK2. 293T cells were transfected with Flag-HIPK2 together with increasing amounts of kinase-dead Src (K297M) and total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. (C) HIPK2 mRNA levels are not altered upon Src overexpression. 293T cells were transfected with Flag-HIPK2 either together with kinase-active Src (Y527F) or empty vector control. Total RNA was purified and mRNA levels of HIPK2 and actin were analyzed by RT-PCR using ethidium bromide staining. (D) Src prolongs HIPK2 half-life. 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Flag-HIPK2 along with empty vector or kinase-active Src (Y527F), as indicated. Twenty-four hours after transfection cells were treated with 40 µg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for different time points. Equal amounts of total protein lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. The results of 3 independent experiments are summarized in the graph. Standard deviations are indicated. (G) The SFK inhibitor Dasatinib abrogates Src mediated HIPK2 stabilization. 293T cells expressing the indicated proteins were treated with 20 nM Dasatinib or solvent. Immunoprecipitates and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. (H) Endogenous HIPK2 is stabilized upon ectopic Src expression. HCT116 cells were transfected with kinase-active Src (Y527F) and cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting.

To address whether Src regulates HIPK2 protein half-life (t1/2), we determined HIPK2 half-life in absence and presence of Src expression by inhibition of de novo protein synthesis with cycloheximide and analyzed the remaining HIPK2 protein levels by immunoblotting. Indeed, Src expression strongly increased the half-life of HIPK2 from 27 min to 155 min (Fig. 3D and E). Treatment with the small-molecule Src inhibitor Dasatinib suppressed the stabilizing effect of Src on HIPK2 (Fig. 3E), indicating that this effect requires the kinase function of Src. In addition, we also confirmed the stabilizing effect of Src on the endogenous HIPK2 protein expressed in HCT116 cells (Fig. 3F). Taken together, these results indicate that Src regulates HIPK2 protein stability.

Src interferes with HIPK2 degradation mediated by the ubiquitin ligase Siah-1

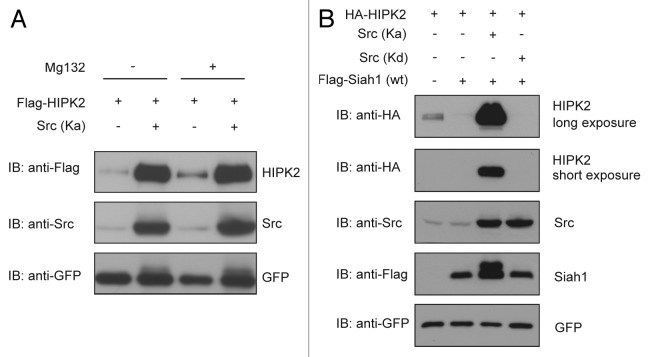

To analyze whether Src might regulate HIPK2 stability by interference with proteasome-dependent degradation of HIPK2, we compared the effect of Src expression on HIPK2 protein levels to the effect of proteasome inhibition. Interestingly, Src expression resulted in a comparable increase in HIPK2 protein levels as proteasome inhibition (Fig. 4A), suggesting that Src might interfere with HIPK2 degradation.

Figure 4. Src prevents Siah-1 mediated HIPK2 decay. (A) 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing Flag-HIPK2 and kinase-active Src (Y527F). After 24 h, cells were treated with 20 µM of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 or DMSO for 4 h. Cells lysates were collected and analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (B) Src prevents HIPK2 degradation in the presence of Siah-1 expression. 293T cells were transfected with plasmids expressing HA-HIPK2, Flag-Siah1 together with kinase-active Src (Y527F) or kinase-dead Src (K297M), as indicated. Cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting.

Since HIPK2 stability is regulated by the ubiquitin ligase Siah-1,13,14 we next tested whether Src expression interferes with Siah-1-mediated HIPK2 proteolysis. Indeed, coexpression of active Src efficiently interfered with HIPK2 degradation stimulated by ectopic expression of Siah-1 (Fig. 4B). In contrast, a kinase-dead Src kinase failed to protect HIPK2 from degradation mediated by Siah-1 (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that Src protects HIPK2 from Siah-1-mediated degradation in a kinase activity-dependent fashion. Interestingly, we observed that expression of activated Src, but not kinase-dead Src, resulted in a slower migrating, presumably phosphorylated Siah-1 isoform (Fig. 4B). In line with this assumption, a previous report showed that Siah-1 is Tyr-phosphorylated at multiple residues by Src, which modulates Siah-1 activity.24 Taken together, our data suggest that Src inhibits HIPK2 degradation by counteracting the function of the ubiquitin ligase Siah-1.

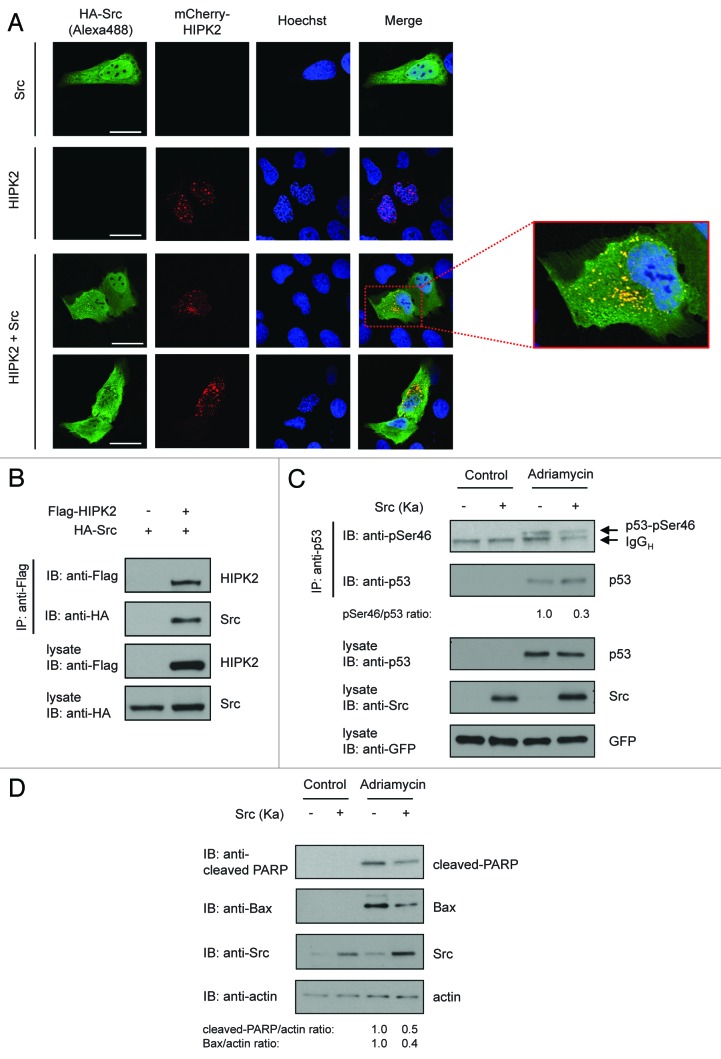

Src interacts with HIPK2, redistributes HIPK2 into the cytoplasm and counteracts adriamycin-induced p53 Ser46 phosphorylation and apoptosis

HIPK2 is well established as a nuclear body localized protein. Furthermore, nuclear localization of HIPK2 is critical for its function in p53 Ser46 phosphorylation. To determine whether Src expression modulates the subcellular localization of HIPK2, we performed immunofluorescence stainings. While HIPK2 localized preferentially to the cell nucleus and nuclear bodies, Src showed a heterogeneous localization both in the cytoplasm and the cell nucleus (Fig. 5A). Intriguingly, upon coexpression of Src, HIPK2 was clearly relocated to the cytoplasm, where it partially colocalized with Src (Fig. 5A). In line with this finding, coimmunoprecipitation analysis revealed that Src and HIPK2 form a complex (Fig. 5B). Together, these results suggest that Src relocates HIPK2 from the cell nucleus into the cytoplasm, which may affect its function in p53 Ser46 phosphorylation upon DNA damage.

Figure 5. Src interacts with HIPK2, redistributes HIPK2 into the cytoplasm and modulates chemotherapeutic drug-induced p53 Ser46 phosphorylation and apoptosis. (A) Src expression redistributes HIPK2 into the cytoplasm. U2OS cells were transfected with mCherry-HIPK2 (red) along with HA-Src (green). The subcellular distribution was analyzed 24 h post-transfection after fixation by autofluorescence of mCherry (HIPK2) or by indirect immunofluorescence staining (Src). DNA was visualized by Hoechst staining. Representative images are shown. Scale bar = 20 µm (B) Interaction of ectopically expressed HIPK2 and Src. Flag-HIPK2 and HA-Src were expressed in 293T cells. Flag-HIPK2 was precipitated from lysates and binding of HA-Src to Flag-HIPK2 was measured by immunoblot analysis. (C) Src expression diminishes p53 Ser46 phosphorylation after DNA damage. Kinase-active Src (Y527F) was expressed in HCT116 cells and treated with adriamycin (1 µg/ml) or solvent for 24 h. Endogenous p53 was precipitated from lysates and immunoprecipitates along with total cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. The relative p53 Ser46/p53 ratio was determined by densitometry. (D) Src inhibits chemotherapeutic drug-induced Bax regulation and apoptosis. HCT116 cells were transfected and treated as indicated. Twenty-four hours post-adriamycin treatment (1 µg/ml) cells were harvested and analyzed by immunoblotting. The relative cleaved PARP/actin and Bax/actin ratios were determined by densitometry.

Thus, we next investigated the effect of Src on p53 Ser46 phosphorylation stimulated by treatment with the chemotherapeutic drug adriamycin in HCT116 colon carcinoma cells. Remarkably, expression of Src resulted in reduced p53 Ser46 phosphorylation in response to adriamycin treatment, indicating that Src can interfere with this pro-apoptotic p53 phosphorylation mark (Fig. 5C). In addition, ectopic expression of active Src suppressed cleavage of the caspase substrate PARP and inhibited induction of the proapoptotic Bcl2 family protein Bax, a well-known p53 target gene (Fig. 5D). Taken together, these data indicate that Src expression inhibits chemotherapeutic drug-induced p53 Ser46 phosphorylation and induction of apoptosis, presumably by modulating HIPK2 localization.

Discussion

The Ser/Thr protein kinase HIPK2 is an emerging tumor suppressor and mediator of DNA damage-induced cell death.16,17,25-28 There is accumulating evidence that HIPK2 determines the sensitivity of tumor cells through regulating the p53 pathway. However, whether prominent oncoproteins, such as the Src kinase, may modulate HIPK2 function has not been investigated so far.

Regulation of HIPK2 by Src kinase

Our results presented here indicate that the proto-oncogenic non-receptor kinase Tyr kinase Src phosphorylates HIPK2 at multiple Tyr residues. Previous reports have demonstrated that HIPK2 has a cryptic cis-regulatory Tyr kinase activity and is capable of autophosphorylating Tyr354 within its activation loop, which is important for activation of its kinase activity.22,23 A similar transient mechanism of cis-autoactivation by Tyr-phosphorylation has been previously described for the Ser/Thr kinase DYRK2.29 Using mass spectrometry and phospho-specific antibodies, we demonstrate that Tyr354 is also a target for phosphorylation by Src kinase in trans. Tyr354 is critical for HIPK2 activity.22,23 Accordingly, HIPK2Y354F shows reduced potential to phosphorylate p53 at Ser46, although it did not show complete loss of its p53-phosphorylating activity suggesting residual kinase activity (not shown). Why Src kinase stabilizes HIPK2 and potentially mediates HIPK2 activation by phosphorylating Tyr354 is unclear. Since Src phosphorylates numerous additional Tyr residues in the HIPK2 kinase domain and adjacent domains, it will be important in the future to determine the impact of these sites on HIPK2 activity and localization.

Of note, we observed that Src kinase stabilizes HIPK2 and relocates the kinase into the cytoplasm. The biological functions of HIPK2 in the cytoplasm are currently unknown. One might speculate that cytoplasmic HIPK2 exerts functions different from its nuclear counterpart. It is tempting to speculate that HIPK2 exerts dual function depending on its subcellular distribution, with the nuclear kinase being tumor-suppressive and the cytoplasmic kinase being potentially growth-supportive. Future experiments will be required to shed light into this provocative hypothesis.

Modulation of HIPK2 function by cellular and viral oncogenes

Relocation of HIPK2 by the expression of oncoproteins has been described in a previous study. The leukemogenic fusion protein CBF-β-SMMHC, which is associated with development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), was found to delocalize HIPK2 into filamentous structures in the cytoplasm, which presumably interferes with the tumor-suppressive functions of HIPK2.30 The viral E6 oncoprotein of human papilloma virus 23 (HPV23), a cutaneous papilloma virus found in warty-like neoplasms of the skin, interacts with HIPK2 and prevents p53 Ser46 phosphorylation by disrupting the HIPK2-p53 protein complex.31

Thus, interference with HIPK2 function appears to be a more general mechanism of oncoproteins. These findings suggest that HIPK2 inactivation does not require mutation of the HIPK2 gene, but it is presumably a more common feature of oncoproteins to compromise HIPK2 function by different mechanisms, preferentially by altering HIPK2 subcellular localization. In fact, HIPK2 has been found to be only rarely mutated in human cancer.32

In summary, our study defines a novel pathway of HIPK2 regulation, through the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Src. Src is overexpressed in numerous cancer cells and has been implicated in cellular transformation, invasion, and carcinogenesis. Previous studies have proposed a number of apoptotic and growth-suppressive substrates, such as caspase-8 and p27KIP1,33,34 which are deregulated by Src kinase. Our finding that Src deregulates the apoptotic kinase HIPK2, which is an important regulator of radio- and chemosensitivity in cancer cells,35 provides novel insight into the mechanisms by which Src mediates its growth-stimulatory, anti-apoptotic effects to promote carcinogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, transfection, and treatments

293T, H1299, HCT116, and U2OS cells (all obtained from ATTC) were propagated in DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 20 mM Hepes buffer, 50 units/ml penicillin, and 50 units/ml streptomycin. Cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes for biochemical analysis. Transient transfections were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or by standard calcium phosphate precipitation. Cells were harvested for immunoblotting or immunocytochemistry 24 h after transfection if not otherwise stated. For induction of DNA damage, cells were incubated with culture medium supplemented with adriamycin (Sigma) at the specified concentrations. The SFK inhibitor Dasatinib (Selleck Chemicals) was dissolved in DMSO. Control treatments were done with the same amounts of the solvent(s), respectively.

Antibodies

The following antibodies were used: p53 (DO-1 and FL393), GST (Z5), GFP (FL), tubulin (H-239) from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, anti-phospho-Tyr (4G10) antibody from Millipore, anti-phospho-Ser46 p53 from BD PharMingen, Flag (M2) from Sigma, HA (12CA5 and 3F10) from Roche Diagnostics, actin (C4) from MP Biomedicals, c-Src (L4A1) and Bax from Cell Signaling Technologies, and cleaved PARP (Y34) from Abcam. Affinity purified HIPK2 antibodies have been described previously.13 The affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal phospho-Tyr354 HIPK2 antibody was generated by immunizing rabbits with the following KLH-coupled peptide contained in human HIPK2: H2N-CST(pY)LQSR-CONH2. Rabbit sera were affinity-purified against the phospho-peptide and subsequently non-phosphorylation specific antibodies were removed by a column containing the immobilized non-phospho-peptide.

In vitro kinase assays

Flag-tagged HIPK2 proteins were immunopurified from 293T cells and incubated in 30 μl kinase reaction buffer containing 40 µM ATP, 20 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.4, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM MgCl2, 5 mM MnCl2, 0.5 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM DTT, and 5 μCi [γ-32P] ATP and 200 ng of bacterially expressed and purified GST-Src (Cell Singaling Technologies). After incubation for 30 min at 30 °C, the reaction was stopped by adding 5× Laemmli buffer. After separation by SDS-PAGE, gels were fixed, dried, and exposed to X-ray films (Fuji).

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy were essentially performed as described.21 U2OS cells were seeded on coverslips in 24-well plates, approximately 2 × 105 cells per well. Cells were transfected on the next day, and 24 h later, cells were fixed in fresh 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS buffer for 20 min. Fixed samples were permeabilized in 0.5% Triton-X-100 in PBS for 10 min and blocked with 5% BSA in PBS. Incubation with primary antibodies was performed overnight at 4 °C. The next day, coverslips were washed in PBS and subsequently incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at 20 °C. The following secondary antibody was used: Alexa-488-coupled goat anti-mouse (Invitrogen). Nuclear staining was performed using Hoechst dye. Coverslips were mounted with Mowiol (Sigma) and cells were visualized using an Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope and processed with ImageJ software.

Expression constructs

The HIPK2, p53 and Siah-1 constructs have been described previously.13,16,21 HIPK2 Y354F mutant was generated using site-directed mutagenesis and standard PCR techniques. Src kinase-dead (K297M) and kinase-active (Y527F) mutants were kindly provided by Dr Nina Reuven. Wild-type c-Src and c-Fyn constructs were generated by shuttling Gateway Full ORF clones (Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility, German Cancer Research Center) into the respective destination vector using the Gateway (Invitrogen) recombination system. All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

RT-PCR

RT-PCR against HIPK2 and actin was performed using total RNA extracted with RNA extraction kit (Qiagen) as published.21

Determination of protein half-life

293T cells were transfected with Flag-HIPK2 plasmid along with Src kinase-active (Y527F) or empty vector control. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were treated with 40 µg/ml cycloheximide (Sigma) for different time points. Cells were harvested, and cell extracts were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Values were calculated by densitometric analysis using ImageJ software, and curves were obtained by nonlinear regression using GraphPad PRISM software (GraphPad Software, Inc). These data represent the average of 3 replicates.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

Immunoblotting and sample preparations were performed as previously described (ref. 13). Proteins were detected by Western Lightning Plus-ECL (Perkin Elmer) and enhanced chemiluminescence Super Signal West Dura and Femto (Pierce). Immunoprecipitation experiments were performed in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7,4, 10% glycerol, 1% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 1×. Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma) and mouse IgG TrueBlot (eBiosciences) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Reactions were incubated for 2 h at 4 °C on a rotating wheel and washed 3 times in lysis buffer. Samples were prepared for immunoblotting by adding 5× Laemmli buffer and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min.

Sample preparation for mass spectrometry

293T cells were transfected to express Flag-HIPK2 in presence or absence of kinase-active Src, followed by immunoprecipitation using anti-Flag M2 affinity gel in buffer containing 25 mM sodium fluoride and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate in order to maintain phosphorylation. Proteins were eluted from sepharose beads using 200 µg/ml Flag-peptide (Sigma). Eluates were separated by SDS-PAGE. The bands were cut from the gel with a clean scalpel. Gel pieces were then cut into 1-mm cubes for preparation prior to in-gel digestion. Reagents were prepared in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate for the trypsin digestion, 100 mM TrisHCl, 10 mM CaCl2 (pH 8) for the chymotrypsin digestion, and 50 mM TrisHCl, 10 mM CaCl2 (pH 8) for the Arg C digestion. The gel pieces were first washed with water, then shrunk with acetonitrile prior to reduction using DTT (56 °C, 30 min, 10 mM). The gel pieces were then shrunk again with acetonitrile and alkylated with iodacetamide (room temperature, in the dark, 20 min, 55 mM). After shrinking again with acetonitrile, the samples were placed on ice, and a volume (sufficient to cover the gel pieces) of the chosen enzyme solution solution (1 ng/µL solution in digestion buffer) was added. The gel pieces were allowed to swell on ice for 30 min, after which they were placed in a shaker overnight at 37 °C (trypsin and Arg C) or room temperature (chymotrypsin) for digestion to take place. On the next day, peptides were extracted from the gel pieces. Samples were sonicated for 15 min, centrifuged, and the supernatant removed and placed in a clean tube. Then a solution of 50:50 water: acetonitrile, 1% formic acid (2× the volume of the gel pieces) was added, and the samples were again sonicated for 15 min and centrifuged, and the supernatant pooled with the first extract. The pooled supernatants were then dried down with the speed vacuum centrifuge. The samples were then dissolved in 20 µL of reconstitution buffer (96:4 water: acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid and analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

LC-MS/MS

Peptides were separated using the Proxeon EasyNanoLC system (Thermo Fisher) fitted with a trapping column (self-packed Hydro-RP C18 (Phenomenex), 100 µm × 2.5 cm, 4 µm) and an analytical column (self-packed Reprosil C18, Dr Maisch) 75 µm × 15 cm, 3 µm, 100 Å). Solvent A was water, 0.1% formic acid and solvent B was acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid. The samples (8 µL) were loaded with a constant pressure (280 bar) of solvent A with a total volume of 15 µL onto the trapping column. Peptides were eluted via the analytical column a constant flow of 0.3 µL/min. During the elution step, the percentage of solvent B increased in a linear fashion from 4–40% B in 20 min. The outlet of the analytical column was coupled directly to the mass spectrometer (Orbitrap Velos, Thermo Scientific) via a Pico-Tip Emitter (360 µm OD × 20 µm ID; 10 µm tip [New Objective]) and a spray voltage of 2.1 kV was applied. The capillary temperature was set at 230 °C. Full scan MS spectra with mass range 300–1700 m/z were acquired in profile mode in the FT with resolution of 30 000. The filling time was set at maximum of 500 ms with limitation of 106 ions. The most intense ions (up to 15) from the full scan MS were selected for sequencing (either in HCD collision cell or in the LTQ (CID). Normalized collision energy of 40% was used, and the fragmentation was performed after accumulation of 1 × 104 (CID) or 3 × 104 (HCD) ions or after filling time of 100 ms (CID) or 150 ms (HCD) for each precursor ion (whichever occurred first). MS/MS data was acquired in centroid mode for CID or profile mode with 7500 resolution in the orbitrap (HCD). Only multiply charged (2+, 3+, 4+) precursor ions were selected for MS/MS. The dynamic exclusion list was restricted to 500 entries with maximum retention period of 30 s and relative mass window of 10 ppm. In order to improve the mass accuracy, a lock mass correction using a background ion (m/z 445.12003) was applied.

Data processing

Software MaxQuant (version 1.1.1.36) was used for processing the data. The data were searched against Uniprot human database with the following modifications: carbamidomethyl (C) (fixed) and phospho (STY) and oxidation (M) (variable). The mass error tolerance for the full scan MS spectra was set at 20 ppm and for the MS/MS spectra at 0.5 Da (CID) and 20 ppm (HCD). A maximum of 2 missed cleavages (trypsin/ArgC) and 3 missed cleavages (chymotrypsin) were allowed. Only the phosphorylation sites with a probability score higher than 0.75 and a score difference (delta score) higher than 5 were considered.36

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr N Reuven and Prof Y Shaul (Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel) for discussion and providing expression vectors encoding kinase-active and kinase-dead Src, Jana Sonner for help with an experiment and Dr Elisa Conrad and Ansam Sinjab for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the DKFZ-MOST Program and the Deutsche Krebshilfe (108528).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/cc/article/26857

References

- 1.Parsons SJ, Parsons JT. Src family kinases, key regulators of signal transduction. Oncogene. 2004;23:7906–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tice DA, Biscardi JS, Nickles AL, Parsons SJ. Mechanism of biological synergy between cellular Src and epidermal growth factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:1415–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishizawar R, Parsons SJ. c-Src and cooperating partners in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:209–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang S, Huang WC, Li P, Guo H, Poh SB, Brady SW, Xiong Y, Tseng LM, Li SH, Ding Z, et al. Combating trastuzumab resistance by targeting SRC, a common node downstream of multiple resistance pathways. Nat Med. 2011;17:461–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang S, Yu D. Targeting Src family kinases in anti-cancer therapies: turning promise into triumph. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33:122–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kmiecik TE, Shalloway D. Activation and suppression of pp60c-src transforming ability by mutation of its primary sites of tyrosine phosphorylation. Cell. 1987;49:65–73. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90756-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kmiecik TE, Johnson PJ, Shalloway D. Regulation by the autophosphorylation site in overexpressed pp60c-src. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:4541–6. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.10.4541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hofmann TG, Glas C, Bitomsky N. HIPK2: A tumour suppressor that controls DNA damage-induced cell fate and cytokinesis. Bioessays. 2013;35:55–64. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calzado MA, de la Vega L, Möller A, Bowtell DD, Schmitz ML. An inducible autoregulatory loop between HIPK2 and Siah2 at the apex of the hypoxic response. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:85–91. doi: 10.1038/ncb1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hikasa H, Ezan J, Itoh K, Li X, Klymkowsky MW, Sokol SY. Regulation of TCF3 by Wnt-dependent phosphorylation during vertebrate axis specification. Dev Cell. 2010;19:521–32. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bitomsky N, Hofmann TG. Apoptosis and autophagy: Regulation of apoptosis by DNA damage signalling - roles of p53, p73 and HIPK2. FEBS J. 2009;276:6074–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dauth I, Krüger J, Hofmann TG. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 is the ionizing radiation-activated p53 serine 46 kinase and is regulated by ATM. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2274–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winter M, Sombroek D, Dauth I, Moehlenbrink J, Scheuermann K, Crone J, Hofmann TG. Control of HIPK2 stability by ubiquitin ligase Siah-1 and checkpoint kinases ATM and ATR. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:812–24. doi: 10.1038/ncb1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi DW, Seo YM, Kim EA, Sung KS, Ahn JW, Park SJ, Lee SR, Choi CY. Ubiquitination and degradation of homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 by WD40 repeat/SOCS box protein WSB-1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4682–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708873200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bitomsky N, Conrad E, Moritz C, Polonio-Vallon T, Sombroek D, Schultheiss K, Glas C, Greiner V, Herbel C, Mantovani F, et al. Autophosphorylation and Pin1 binding coordinate DNA damage-induced HIPK2 activation and cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 doi: 10.1038/ncb715. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hofmann TG, Möller A, Sirma H, Zentgraf H, Taya Y, Dröge W, Will H, Schmitz ML. Regulation of p53 activity by its interaction with homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:1–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Orazi G, Cecchinelli B, Bruno T, Manni I, Higashimoto Y, Saito S, Gostissa M, Coen S, Marchetti A, Del Sal G, et al. Homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 phosphorylates p53 at Ser 46 and mediates apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:11–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Möller A, Sirma H, Hofmann TG, Rueffer S, Klimczak E, Dröge W, Will H, Schmitz ML. PML is required for homeodomain-interacting protein kinase 2 (HIPK2)-mediated p53 phosphorylation and cell cycle arrest but is dispensable for the formation of HIPK domains. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4310–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krieghoff-Henning E, Hofmann TG. Role of nuclear bodies in apoptosis signalling. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:2185–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernardi R, Papa A, Pandolfi PP. Regulation of apoptosis by PML and the PML-NBs. Oncogene. 2008;27:6299–312. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crone J, Glas C, Schultheiss K, Moehlenbrink J, Krieghoff-Henning E, Hofmann TG. Zyxin is a critical regulator of the apoptotic HIPK2-p53 signaling axis. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2350–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siepi F, Gatti V, Camerini S, Crescenzi M, Soddu S. HIPK2 catalytic activity and subcellular localization are regulated by activation-loop Y354 autophosphorylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:1443–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saul VV, de la Vega L, Milanovic M, Krüger M, Braun T, Fritz-Wolf K, Becker K, Schmitz ML. HIPK2 kinase activity depends on cis-autophosphorylation of its activation loop. J Mol Cell Biol. 2013;5:27–38. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yun S, Möller A, Chae SK, Hong WP, Bae YJ, Bowtell DD, Ryu SH, Suh PG. Siah proteins induce the epidermal growth factor-dependent degradation of phospholipase Cepsilon. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1034–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Q, Yoshimatsu Y, Hildebrand J, Frisch SM, Goodman RH. Homeodomain interacting protein kinase 2 promotes apoptosis by downregulating the transcriptional corepressor CtBP. Cell. 2003;115:177–86. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00802-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mao JH, Wu D, Kim IJ, Kang HC, Wei G, Climent J, Kumar A, Pelorosso FG, DelRosario R, Huang EJ, et al. Hipk2 cooperates with p53 to suppress γ-ray radiation-induced mouse thymic lymphoma. Oncogene. 2012;31:1176–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lavra L, Rinaldo C, Ulivieri A, Luciani E, Fidanza P, Giacomelli L, Bellotti C, Ricci A, Trovato M, Soddu S, et al. The loss of the p53 activator HIPK2 is responsible for galectin-3 overexpression in well differentiated thyroid carcinomas. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei G, Ku S, Ma GK, Saito S, Tang AA, Zhang J, Mao JH, Appella E, Balmain A, Huang EJ. HIPK2 represses beta-catenin-mediated transcription, epidermal stem cell expansion, and skin tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13040–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703213104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lochhead PA, Sibbet G, Morrice N, Cleghon V. Activation-loop autophosphorylation is mediated by a novel transitional intermediate form of DYRKs. Cell. 2005;121:925–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wee HJ, Voon DC, Bae SC, Ito Y. PEBP2-beta/CBF-beta-dependent phosphorylation of RUNX1 and p300 by HIPK2: implications for leukemogenesis. Blood. 2008;112:3777–87. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-134122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muschik D, Braspenning-Wesch I, Stockfleth E, Rösl F, Hofmann TG, Nindl I. Cutaneous HPV23 E6 prevents p53 phosphorylation through interaction with HIPK2. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27655. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li XL, Arai Y, Harada H, Shima Y, Yoshida H, Rokudai S, Aikawa Y, Kimura A, Kitabayashi I. Mutations of the HIPK2 gene in acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome impair AML1- and p53-mediated transcription. Oncogene. 2007;26:7231–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cursi S, Rufini A, Stagni V, Condò I, Matafora V, Bachi A, Bonifazi AP, Coppola L, Superti-Furga G, Testi R, et al. Src kinase phosphorylates Caspase-8 on Tyr380: a novel mechanism of apoptosis suppression. EMBO J. 2006;25:1895–905. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chu I, Sun J, Arnaout A, Kahn H, Hanna W, Narod S, Sun P, Tan CK, Hengst L, Slingerland J. p27 phosphorylation by Src regulates inhibition of cyclin E-Cdk2. Cell. 2007;128:281–94. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krieghoff-Henning E, Hofmann TG. HIPK2 and cancer cell resistance to therapy. Future Oncol. 2008;4:751–4. doi: 10.2217/14796694.4.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marchini FK, de Godoy LM, Rampazzo RC, Pavoni DP, Probst CM, Gnad F, Mann M, Krieger MA. Profiling the Trypanosoma cruzi phosphoproteome. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25381. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]