Abstract

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease initiated by host-parasite interactions which contributes to connective tissue destruction and alveolar bone resorption. Porphyromonas gingivalis (P.g.), a black-pigmented Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium, is a major pathogen in the development and progression of periodontitis. To characterize the role that Porphyromonas gingivalis and its cell surface components play in disease processes, we investigated the differential expression of proteins induced by live P.g., P.g LPS and P.g FimA, using two dimensional gel electrophoresis in combination with mass spectrometry. We have tested whether, at the level of protein expression, unique signaling pathways are differentially induced by the bacterial components P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA, as compared to live P.g..

We found that P.g. LPS stimulation of THP-1 up-regulated the expression of a set of proteins compared to control: deoxyribonuclease, actin, carbonic anhydrase 2, alpha enolase, adenylyl cyclase-associated protein (CAP1), protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), glucose regulated protein (grp78) and 70-kDa heat shock protein (HSP70), whereas FimA treatment did not result in statistically significant changes to protein levels versus the control. Live P.g. stimulation resulted in 12 differentially expressed proteins: CAP1, tubulin beta-2 chain, ATP synthase beta chain, tubulin alpha-6 chain, PDI, vimentin, 60-kDa heat shock protein and nucleolin were found to be up-regulated, while carbonic anhydrase II, beta-actin and HSP70 were down-regulated relative to control. These differential changes by the bacteria and its components are interpreted as preferential signal pathway activation in host immune/inflammatory responses to P.g. infection.

Keywords: Lipopolysaccharide, mass spectrometry, monocytes/macrophages, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Toll-like receptors, proteomics

Introduction

Periodontitis is an inflammatory disease in which genetic, microbial, immunological and environmental factors combine to influence disease risk, progression and course. Connective tissue damage and alveolar bone resorption are characteristic of this disease, due to a destructive innate host response to pathogenic bacterial virulence. Porphyromonas gingivalis (P.g.), a black-pigmented Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium, is a major pathogen in the development and progression of periodontitis. The prevailing current interpretation of P.g. infectivity is that the structures on its cell wall and appendage, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and fimbriae (FimA) contribute to P.g.’s virulence. These components play crucial roles in the induction of innate immune responses, including cytokine production by localized and circulating monocytes/macrophages (1).

LPS is a major component of the outer membrane of P.g. It is known to penetrate the periodontal tissues and subsequently interacts with host immune cells and non-immune cells, leading to host immune activation. FimA, a peritrichous filamentous appendage, mediates the adherence of bacteria to host cells, and to variety of oral substrates and molecules (2). LPS and FimA clearly possess pattern recognition characteristics, and have long been known to interact with the host immune system. Numerous studies have shown that the host uses these molecules to detect both microbial colonization and infection. They play important roles in the induction of humoral and cellular immune responses, including recruitment of peripheral leukocytes, induction of cytokine synthesis (3), and activation of inflammation-related signaling pathways (4).

Understanding the molecular basis of the host response to bacterial infections is critical for preventing both infection and the resulting tissue damage. The cellular and molecular events that occur during the interaction of individual pathogenic components with host monocytes/macrophages have been characterized to some extent. Although LPS is generally considered a bacterial component that stimulates host response to infection, P.g. LPS is not as potent an activator of human monocytes a is E. coli LPS (5). P.g. LPS may thus selectively modify the host response as a means to facilitate colonization.

P.g. FimA activates human monocytes through using specific cellular receptors (6), and phosphorylated proteins (7). P.g. FimA induces monocyte adhesion to the endothelial cell surface and infiltrates monocytes into periodontal tissues of periodontitis patients (8).

Although information is available on monocyte response to P.g. bacterial components LPS and FimA (6–8), very little is known on the monocyte response to the live P.g. bacteria. Our laboratory has previously shown quantitative and qualitative differences in monocyte responses to live P.g. and its LPS and FimA, supporting the hypothesis that live P.g. stimulates unique pro-inflammatory signal transduction pathways in human monocytes, as opposed to their response to individual components of the bacteria. (9). Therefore, a more comprehensive understanding of host-P.g. interactions is warranted to bridge the gap in information relevant to live bacteria.

Expression proteomics aims at identifying and quantifying the amount of each protein present within normal cells, diseased cells, and cells manipulated through experimental conditions. Mass spectrometry (MS) has become a major analytical tool in proteomic studies. It is typically employed in combination with two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2-DGE) and bioinformatics to quantify and identify proteins that are expressed in cells or tissues. Any changes that can occur during signaling, such as post-translational modifications (PTMs), expression levels, proteolytic processing and alternative message splicing can be monitored using the electrophoretic profile from 2-DGE and the proteins identified by MS (10). Therefore, in the same experiment, the targets of signaling pathways can be identified on the basis of alterations in their transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation, giving insight into how signaling events elicit biological responses. In a study that relates closely to the research discussed herein, the proteomics approach has been successful for elucidating the novel mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway effectors (11).

To increase our understanding of the mechanisms by which human monocytes interact with live P.g., we investigated which proteins are differentially modulated after treatment with live P.g. relative to its purified LPS or fimbrial components. We employed a proteomic approach to evaluate the effect of live P.g., P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA on protein expression profiles of differentiated THP-1 cells analyzed by 2-DGE and MS. Qualitative and semi-quantitative comparisons of the proteins expressed in response to exposure to live P.g., P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA were obtained.

Experimental Section

Bacterial strain and culture conditions

P. g. was grown in brain/heart infusion broth (P. gingivalis 381) or Schaedler broth (P. gingivalis A7436) enriched with hemin (5 μg/ml) and menadione (1 μg/ml) in an anaerobic atmosphere (85% N2, 10% H2, 5% CO2) for 24 h at 37 °C. For infection experiments, P. g. 381 was grown until the culture reached an optical density at 660 nm of 0.8; it was then pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in sterile 20% glycerol to make frozen stocks that were thawed for the experiments.

Purification of FimA

FimA was purified to homogeneity by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of sonicated extracts of P. g. 381 or P. g. A7436 as described earlier (12). Briefly, The crude fimbriae preparation (about 500 mg/ml) was subjected to reversed-phase HPLC (System Gold® HPLC, Beckman Coulter) separation using a semi-preparative, wide-pore C8, (10 mm × 250 mm) Vydac column and eluted with a gradient of solvent B (0.1% TFA in ACN) in solvent A (0.1% TFA in HPLC grade water) for 70 min with a flow rate of 1 ml/min at room temperature. The identity of the 41-kDa FimA was confirmed by N-terminal amino acid sequencing, and its molecular weight was determined by matrix-assisted laser-desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). The total fimbrial protein was quantified by using a NanoOrange protein quantification kit (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Monocytes did not respond differently to HPLC-purified FimA compared to native FimA.

Preparation of LPS

LPS from P. gingivalis 381 and P. gingivalis A7436 were purified by phenol-water extraction and subsequent treatment with DNase I, RNase A, and proteinase K, followed by cesium chloride isopyknic density gradient centrifugation. The fractions with a density of 1.42 to 1.52 g/cm3, which contained peak endotoxin activity, as determined by the Limulus amebocyte clotting assay, were pooled, dialyzed, lyophilized, and repurified by the method of Manthey and Vogel (13) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE with silver staining. The absence of proteinacous contamination was confirmed by amino acid analysis. The molecular weight of LPS was estimated by using gas chromatography (GC) to determine the number of moles of hexadecanoic acid (16:0) in a given weight of LPS.

Cell Culture

THP-1 human monocytic cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS, and maintained in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After 3 – 4 days of growth, THP-1 cells were harvested. THP-1 cells at 1 × 107 were distributed among eight 100-mm plates in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FCS. The cells were maturated by exposure to phorbol-12-myristate-13 acetate (PMA) (20 ng/ml) for 24 h. The maturation process prepares the cells to actively participate in the inflammatory and immune responses. The RPMI-1640 medium was replaced one hour before an experiment. LPS (10 μg/ml) and FimA (10 μg/ml) were added and one plate of THP-1 cells was left untreated for control. Adherent differentiated THP-1 cells were infected with live P.g. bacteria at a ratio of 25:1 (bacteria-to-macrophages) at 37 °C. Frozen stocks of P.g. 381 were thawed, cultured, and diluted in medium to a concentration of 2.5 × 108 bacteria/50 μl, to give multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of 25:1, and added to cultures of macrophages. These concentrations were chosen based on our preliminary data (not shown), where these concentrations of stimuli generated maximal effects of cytokine production by macrophages. Cell extracts were collected after 24 h of stimulation.

Protein sample preparation

After treatment with live P.g., P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA, cells were washed with three times with HBSS and subjected to protein extraction. Two ml of Lysis buffer (6M urea, 2M thiourea, 10% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8–8.2, between 10–25 °C), 2% n-octylglucoside, 5mM TCEP (Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride), 1mM protease inhibitor) was added to each 0.5 ml of cell pellet sample and the cell homogenate was vortexed vigorously. This was followed by centrifuging the solution at 20,000 × g for 60 min while maintaining the temperature ≥18 °C to prevent precipitation of the lysis buffer. The supernatant was removed from the cell debris and stored in a non-frost free freezer at −80 °C until use. Total protein amount was quantified using a modified Bradford protein assay.

Two-dimensional Gel Electrophoresis

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis was carried out by isoelectric focusing (IEF) using pre-made immobilized pH gradient (IPG) strips on a Protean IEF cell (Bio-Rad) followed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using a Protean-II device (Bio-Rad). The reproducibility of 2-DGE was evaluated by preparing 4 replicate gels (n = 4) for each condition. Equal amounts of proteins (400 μg) from control, live P.g., P.g. LPS- and P.g. FimA-stimulated THP-1 monocytes were mixed with 300 μl of IEF rehydration buffer (BioRad) in a focusing tray upon which a 17-cm-long (pH 3–10 ReadyStrip IPG strip, BioRad), pre-made IPG strip was added. Rehydration was carried under active condition (50 V) for 12 h. IEF was performed at 20 °C, at 10,000 V for a total of 70,000 V-hr with a current limit of 50 μA. The focusing was followed by two 10-min SDS equilibration steps, in dithiothreitol (DTT)-containing, and then iodoacetamide-containing equilibration buffers) followed by vertical electrophoresis in 12% PROTEAN II Ready Gel Precast gels at 24 mA/gel for 5 h. Protein spots were visualized by agitation in BioSafe Coomassie Stain (24 h), followed by washing in deionized water, twice (30 min each).

Image Analysis of Two-dimensional Gels

Coomassie stained gels were imaged using Versadoc (BioRad). PD Quest software version 7.1 (Bio-Rad) was used to locate, match and quantify protein spots on the control, LPS and FimA gel images. Spot detection was performed using the spot detection wizard tool in PD Quest software after defining the detection parameters. After spots are detected in PD Quest, the original gel image is filtered and smoothed to clarify the spots by removing horizontal and vertical streaking. Three-dimensional Gaussian spots were then created from the filtered images. There are three images created from this process, the original raw 2-D scan, the filtered image, and the Gaussian image. A matched set was created for comparison after the gel images had been aligned and automatically overlaid. The PD Quest software was then used to identify matched and unmatched spots from all the gels. Visual inspection was also performed to check for errors.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed by Student’s t test for comparison between the replicate groups. Ninety-two percent of the spots were coincident in the four replicates, when the densitometric volume (related to the quantity of protein) of the spots was >200. The pI and relative mobility were reproducible, with variations of 0.6% (± 0.021 pI units) and 3.0%, respectively. The differential up- or down-regulation was identified as significant when the volume ratio of matched spots on two gels was >2.0 or <0.5.

Protease Digestion

Protein spots were excised from the gel and digested using Trypsin Gold, (mass spectrometry grade, Promega, Madison, WI). The resulting tryptic peptides were extracted from the gel with 1% TFA in 50% ACN, and the resulting mixtures were dried using a Speed-Vac™ concentrator (Thermo Savant, Holbrook, NY) (14). The peptides were resuspended in 0.1% TFA, and desalted using ZipTipC18 pipette tips (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The solutions were then dried and the samples were resuspended in 50% ACN, 0.1% TFA for MALDI-TOF MS analysis.

MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry

MALDI-MS studies were performed on a Reflex IV reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA). The matrix was 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid (DHB) or α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (HCCA). Sample deposition was performed using the dried-drop method (15). The nitrogen laser (337 nm) had 3-nsec pulse width. Typically, the signals resulting from 50–100 laser shots were summed for each spectrum using 30–50% relative laser power. Data were processed using MoverZ software (www.genomicsolutions.com) with peak m/z values auto-labeled and saved to an Excel spread sheet for submission to Mascot (Matrix Sciences Ltd., www.matrixscience.com) for peptide mass fingerprinting. Mascot database search parameters were as follows: Database: Swissprot, Taxonomy: Homo sapiens, Enzyme: Trypsin, Missed Cleavage: 1, Fixed Modification: Carbamidomethyl, Variable Modification: Oxidation, Peptide Tolerance: 0.1 Da. Search results returned protein identifications with scores >53 and p<0.05.

SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblotting

The protein contents of cell lysates were determined by the Bradford assay. To detect specific proteins of interest (e.g. glucose regulated protein (grp78), heat shock protein (HSP70), Nucleolin and Carbonic Anhydrase II (CAII)), 25 μg of protein contents of cell lysate were placed in Laemmli sample buffer and loaded into each of 4 different wells of an SDS-PAGE gel (4 to 20% gradient). After electrophoresis, proteins were electrically transferred onto polyvinyl difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore Corp., Bedford, Mass.) in a Tris-glycine–20% methanol buffer for 1.5 h at 4 °C, with a 90 mA current. Membranes were blocked overnight in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 5% dry milk. The membrane was cut into 4 separate lanes and these were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a 1:200 dilution of one of the following antibodies: goat polyclonal grp78 antibody, goat polyclonal HSP 70 antibody, goat polyclonal carbonic anhydrase II, or rabbit polyclonal nucleolin antibody. Membrane strips were then washed and incubated for 1 h with a 1:2,000 dilution of donkey anti-goat IgG-HRP antibody. Proteins were visualized using an ECL system (Pierce Biotechnology).

Results

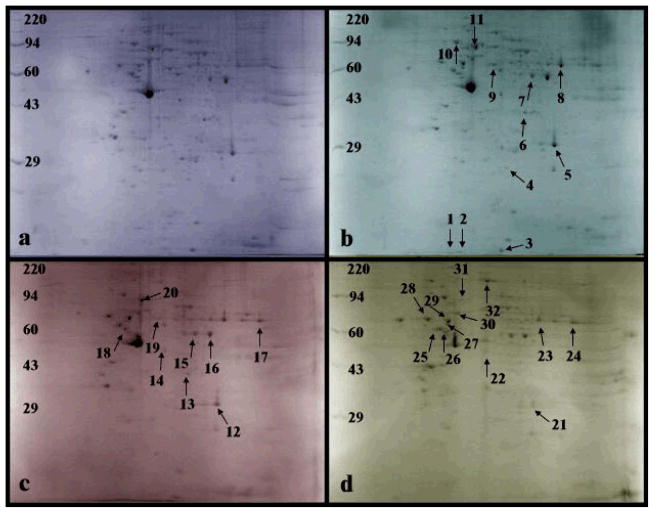

Samples obtained before and after induction with P.g. LPS P.g. FimA and live P.g. were subjected to 2-DGE. Differentially expressed protein spots were excised, in-gel digested with trypsin and identified by MS. Figure 1a shows the 2-DGE separation of proteins extracted from THP-1 prior to P.g. LPS, P.g. FimA or live P.g. stimulation. Figures 1b, 1c and 1d show 2-DGE separations of proteins extracted from THP-1 stimulated with P.g. LPS, P.g. FimA and live P.g., respectively. All four gels showed overall similar protein patterns. These patterns could then be used as landmarks for comparison, making it easier to identify of differentially expressed protein spots by direct visualization. Nevertheless, PD Quest software version 7.1 (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was used for initial location and matching of protein spots. This was followed by visually checking for any potential errors. The electrophoretograms show minimal to no vertical or horizontal streaking and thus minimize the likelihood of misinterpretation of streaks as false protein/peptide spots. Most of the proteins/peptides were distributed between pI 5–8 and between 25 – 80 kDa. Treatment with P.g. LPS resulted in differential expression of eleven protein spots relative to unstimulated controls (Figure 1b), whereas treatment with P.g. FimA caused nine protein spots to be differentially expressed (Figure 1c) and treatment with live P.g. caused twelve protein spots to be differentially expressed (Figure 1d). Spots of interest were excised, in-gel digested with trypsin, and analyzed via MALDI-TOF MS for protein identification.

Figure 1.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (n = 4), using isoelectric focusing with pH range 3–10 in the horizontal dimension and SDS-PAGE (10%) in the vertical dimension, of 400 μg of proteins induced by exposure of differentiated THP-1 cells to (b) LPS (10 μg/ml for 24 h), (c) FimA (10 μg/ml for 24 h), and (d) live P.g. (MOI of 25:1) and stained with Coomassie Blue. Labeled gel spots indicate differentially induced proteins (compared to (a) control) that were cut out for in-gel trypsin digestion and subsequently were analyzed by MS. The protein assignments are listed in Table 1 (protein spots 1–11 are for LPS, protein spots 12–20 are for FimA and protein spots 21–32 are for live P.g.).

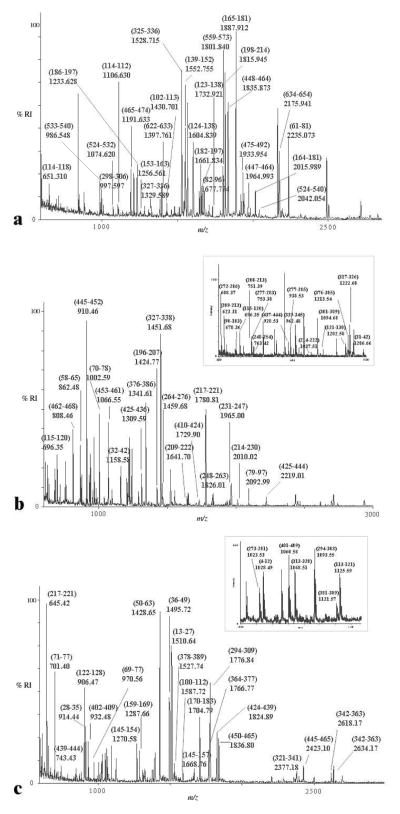

MALDI-TOF MS was used initially to identify protein spots within the gel. In MALDI-MS analyses of the mixtures of peptides generated from digestion of a protein, suppression of certain peptides can occur and therefore lead to poor coverage of the protein sequence. This suppression phenomenon can be attributed to a matrix effect, as well as to competition between peptides for ionization (16). Thus, identical peptide mixtures can produce different spectra depending on the matrix employed and the laser power. Typically, different matrices are used for different classes of peptides. A suitable matrix for peptides with m/z below 2500 is HCCA (16) and DHB is a recommended matrix for hydrophobic peptides (17). In order to increase peptide coverage of protein sequences, both these matrices, HCCA and DHB, were used in the analyses reported here.

Protein identification was achieved via the peptide mass fingerprint (PMF) and database search which is specific enough to identify proteins on the basis of proteolytic peptides (18). Mass spectra were internally calibrated using autolysis tryptic peptides. The Mascot search engine was used in the identification of the proteins. Monoisotopic peptide masses were searched using the SWISS-PROT database with mass tolerance of 0.1 Da. Scores of greater than 53 and above obtained from the Mascot search were assumed to be correct, with a p<0.05 of false positive; the search results were verified by manual inspection. PMF and database search results were obtained on each gel spot/plug for each comparative gel.

Table 1 lists the proteins differentially expressed in THP-1 cells compared to control cells: Section (a) shows results for treatment with P.g. LPS, Section (b) lists the proteins differentially expressed after treatment with P.g. FimA and Section (c) lists the proteins differentially expressed in cells treated with live P.g. Eleven proteins were differentially expressed and found to be up-regulated following treatment of THP-1 cells with P.g. LPS (Table 1. Section a). Expression of 9 proteins changed after treatment with P.g. FimA; these changes seen were small and tended to be down-regulatory, relative to control (Table 1, Section b). Live P.g. stimulation resulted in 12 differentially expressed proteins: adenylyl cyclase-associated protein, tubulin beta-2 chain, ATP synthase beta chain, tubulin alpha-6 chain, protein disulfide isomerase, vimentin, 60-kDa heat shock protein and nucleolin were found to be up-regulated, while carbonic anhydrase II, beta-actin and HSP70 were down-regulated relative to control (Table 1, Section c).

Table 1.

Identification of proteins from (a) LPS-treated (Fig. 1b) (b) FimA-treated (Fig. 1c) and (c) live P.g.-treated (Fig. 1d) THP-1 cells compared to untreated control cells (Fig. 1a).

| 2-D Gel Spot No.a | Treatment Protein Name |

Relative Volumeb (control vs (a) LPS, (b) FimA, (c) live P.g.) | Mr/pI 2-DGEc | Mr/pI Databased | Score Mascot PMF Searche | Masses Matchedf #/(%) | Accession Number Swiss-prot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | LPS | ||||||

| 1 | Deoxyribonuclease | 1:2.02±0.02 | 15.0/5.2 | 29.1/5.1 | 86 | 5(27) | P24855 |

| 2 | Deoxyribonuclease | 1:2.01±0.01 | 16.0/5.2 | 29.1/5.1 | 82 | 5(24) | P24855 |

| 3 | Deoxyribonuclease | 1:2.01±0.02 | 14.0/6.0 | 29.1/5.1 | 92 | 5(33) | P24855 |

| 4 | Actin | 1:3.31±0.03 | 20.0/6.5 | 40.6/5.6 | 99 | 12(26) | P60709 |

| 5 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | 1:5.63±0.07 | 29.0/8.0 | 29.2/6.9 | 136 | 8(33) | P00918 |

| 6 | Annexin A1 | 1:3.29±0.02 | 38.2/6.4 | 38.8/6.6 | 122 | 20 (76) | P04083 |

| 7 | Alpha enolase | 1:6.13±0.05 | 48.0/7.2 | 47.4/7.0 | 215 | 11(18) | P06733 |

| 8 | Adenylyl cyclase- associated protein | 1:14.44±0.07 | 49.0/8.2 | 47.4/7.0 | 80 | 19 (60) | Q01518 |

| 9 | Protein disulfide isomerase | 1:3.23±0.01 | 58.0/6.5 | 57.1/6.0 | 386 | 20(63) | P30101 |

| 10 | Glucose-regulated protein, 78 kDa | 1:6.73±0.03 | 73.0/5.3 | 72.4/5.1 | 244 | 25(39) | P11021 |

| 11 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 isoform 2 | 1:5.88±0.03 | 70.0/5.6 | 71.1/5.4 | 115 | 11(24) | P11142 |

| b | FimA | ||||||

| 12 | Carbonic anhydrase II | 1:0.59±0.03 | 27.0/7.6 | 29.2/6.9 | 136 | 12(46) | P00918 |

| 13 | Annexin A1 | 1:0.70±0.04 | 36.0/7.0 | 38.8/6.6 | 122 | 18(52) | P04083 |

| 14 | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | 1:0.80±0.02 | 43.1/6.3 | 42.1/5.3 | 156 | 15(42) | P60709 |

| 15 | Alpha enolase | 1:0.57±0.03 | 47.0/7.1 | 47.4/7.0 | 201 | 13(31) | P06733 |

| 16 | Alpha enolase | 1:0.52±0.02 | 47.0/7.4 | 47.4/7.0 | 215 | 15(36) | P06733 |

| 17 | Adenylyl cyclase- associated protein | 1:1.31±0.04 | 53.0/8.6 | 51.8/8.1 | 80 | 8(20) | Q01518 |

| 18 | ATP synthase beta | 1:0.86±0.03 | 51.0/5.4 | 56.5/5.3 | 106 | 9(22) | P06576 |

| 19 | Protein disulfide-isomerase A3 | 1:0.92±0.05 | 56.0/6.2 | 57.1/6.0 | 86 | 11(22) | P30101 |

| 20 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 isoform 2 | 1:0.42±0.04 | 75.0/5.6 | 71.1/5.4 | 70 | 25(39) | P11142 |

| c | Live P.g. | ||||||

| 21 | Carbonic anhydrase II | 4.21±0.03:1 | 29.0/8.0 | 29.1/5.1 | 136 | 5(27) | P00918 |

| 22 | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | 2.04±0.04:1 | 44.0/6.1 | 42.1/5.3 | 156 | 15(42) | P60709 |

| 23 | Adenylyl cyclase- associated protein | 1:29±0.03:1 | 63.0/8.2 | 47.4/7.0 | 82 | 6(23) | Q01518 |

| 24 | Adenylyl cyclase- associated protein | 1:6.73±0.04 | 56.0/8.5 | 51.8/8.1 | 80 | 5(15) | Q01518 |

| 25 | Tubulin beta-2 chain | 1:2.04±0.03 | 53.0/4.8 | 50.1/4.8 | 162 | 17(38) | P07437 |

| 26 | ATP synthase beta chain | 1:3.03±0.02 | 57.0/5.1 | 56.5/5.3 | 71 | 7(29) | P06576 |

| 27 | Tubulin alpha-6 chain | 1:2.04±0.03 | 58.0/5.1 | 50.5/5.0 | 80 | 7(22) | Q9BQE3 |

| 28 | Protein disulfide isomerase | 1:2.63±0.04 | 60.0/4.6 | 57.5/4.8 | 421 | 38(55) | P07237 |

| 29 | Vimentin | 1:2.54±0.02 | 58.0/5.1 | 53.5/5.1 | 304 | 31(63) | P08670 |

| 30 | 60 kDa heat shock protein | 1:2.01±0.04 | 62.0/5.5 | 61.1/5.7 | 185 | 24(45) | P10809 |

| 31 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 isoform 2 | 4.48±0.03:1 | 75.0/5.5 | 71.1/5.4 | 70 | 11(24) | P11142 |

| 32 | Nucleolin | 1:2.03±0.07 | 100.0/6.1 | 74.3/4.5 | 99 | 18(29) | P19338 |

The proteins correspond to spots whose volume changed ± two fold after stimulation. Spots (numbered in Fig. 1) were cut from 2-DGE, digested with trypsin and subjected to MALDI-TOF MS for analysis.

Relative volumes of matched spots were determined by PD Quest 7.0 (BioRad).

Apparent mass and pI determined from 2-DGE.

Mass and pI obtained from Swiss-Prot database.

Mascot PMF search parameters are described within the methods. Search results returned the protein identifications shown, using the threshold of scores >53 and p <0.05.

The peptide masses were submitted to the Swiss-Prot database and to the NCBI database. # indicates the number of peptides matched and (%) reports the percent total sequence coverage.

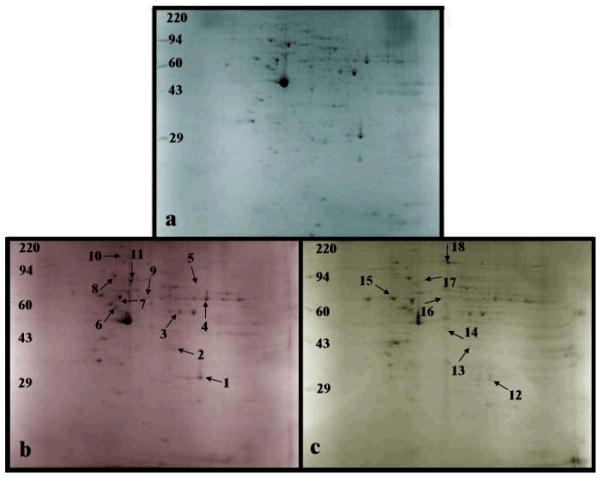

A similar comparison was performed with P.g. LPS stimulation relative to P.g. FimA stimulation. In total, eleven proteins were found to be up-regulated by P.g. LPS in comparison to P.g. FimA: carbonic anhydrase 2, annexin A1, alpha enolase, human, sodium/calcium exchanger 2 precursor, ATP synthase beta, CAP 1, grp78, PDI, microtubule-actin cross linking factor 1, isoforms and HSP70 (Figure 2b and Table 2, Section a). A comparison of P.g. LPS stimulation relative to live P.g. stimulation resulted in seven differentially expressed proteins (Figure 2c, Table 2, Section b). Protein disulfide isomerase and nucleolin were up-regulated while carbonic anhydrase II, annexin, beta-actin, protein disulfide isomerase A3 and HSP70 were down-regulated. Typical protein mass fingerprints are illustrated with the MS profiles of the tryptic peptides obtained by in-gel digestion of a representative protein spot from THP-1 cells treated with P.g. LPS (Figure 3A) and of two representative protein spots from THP-1 cells treated with live P.g. (Figures 3B and 3C).

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (n = 4) using isoelectric focusing with pH range 3–10 in the horizontal dimension and SDS-PAGE (10%) in the vertical dimension of 400 μg of proteins induced by exposure of differentiated THP-1 cells to (b) FimA (10 μg/ml for 24 h), and (c) live P.g. (MOI of 25:1) and stained with Coomassie Blue. Labeled gel spots indicate differentially induced proteins (compared to (a) LPS) that were cut out for in-gel trypsin digestion and subsequently were analyzed by MS. The protein assignments are listed in Table 2 (protein spots 1–11 are for FimA and protein spots 12–18 are for live P.g.).

Table 2.

Identification of proteins from (a) FimA-treated (Fig. 2b) and (b) live P.g.-treated (Fig. 2c) THP-1 cells compared to LPS-treated THP-1 cells (Fig. 2a).

| 2-D Gel Spota | Treatment Protein Name |

Relative Volumeb (treatmernt with LPS vs (a) FimA, (b) live P.g.) | Mr/pI 2-DGEc | Mr/pI Databased | Score Mascot PMF Searche | Masses Matchedf #/(%) | Accession Number Swiss-prot |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | FimA | ||||||

| 1 | Carbonic anhydrase II | 1:5.07±0.04 | 29.0/8.0 | 29.2/6.9 | 152 | 12(46) | P00918 |

| 2 | Annexin A1 | 1:4.39±0.06 | 39.0/6.5 | 38.8/6.6 | 122 | 20 (76) | P04083 |

| 3 | Alpha enolase | 1:10.34±0.06 | 48.0/7.2 | 47.4/7.0 | 215 | 11(18) | P06733 |

| 4 | Adenylyl cyclase- associated protein | 1:3.57±0.04 | 49.0/8.2 | 37.9/6.4 | 80 | 19(60) | Q01518 |

| 5 | Sodium/calcium exchanger 2 | 0:1g | 80.0/8.0 | 101.4/5.0 | 99 | 26(48) | P32418 |

| 6 | ATP synthase beta | 1:7.67±0.03 | 51.0/5.4 | 56.5/5.3 | 71 | 9(22) | P06576 |

| 7 | Tubulin alpha-6 chain | 1:3.56±0.02 | 59.0/5.5 | 50.5/5.0 | 80 | 8(20) | Q9BQE3 |

| 8 | Glucose-regulated protein 78 kDa | 1:11.39±0.07 | 72.4/5.1 | 25(39) | 244 | 25(39) | P11021 |

| 9 | Protein disulfide-isomerase A3 | 1:5.24±0.02 | 56.0/6.2 | 57.1/6.0 | 86 | 11(22) | P30101 |

| 10 | Microtubule-actin cross linking factor 1, isoforms | 1:7.03±0.06 | 16.5/5.2 | 170.6/5.2 | 92 | 26(41) | Q9UPN3 |

| 11 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 isoform 2 | 1:13.87±0.06 | 70.0/5.6 | 71.1/5.4 | 70 | 11(24) | P11142 |

| b | Live P.g. | ||||||

| 12 | Carbonic anhydrase II | 4.73±0.03:1 | 29.0/8.0 | 29.1/5.1 | 136 | 5(27) | P00918 |

| 13 | Annexin A1 | 2.02±0.03:1 | 36.0/7.0 | 38.8/6.6 | 102 | 18(52) | P04083 |

| 14 | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | 2.03±0.02:1 | 44.0/5.8 | 42.1/5.3 | 156 | 15(42) | P60709 |

| 15 | Protein disulfide isomerase | 1:2.29±0.04 | 60.0/4.6 | 57.5/4.8 | 421 | 38(55) | P07237 |

| 16 | Protein disulfide isomerase A3 | 2.03±0.02:1 | 56.0/6.2 | 57.1/6.0 | 86 | 11(22) | P30101 |

| 17 | Heat shock 70 kDa protein 8 isoform 2 | 5.68±0.06:1 | 75.0/5.5 | 71.1/5.4 | 70 | 11(42) | P11142 |

| 18 | Nucleolin | 1:2.63±0.03 | 100.0/6.1 | 74.3/4.5 | 99 | 18(29) | P19338 |

The proteins correspond to spots whose volume changed ± two fold after P.g. FimA and live P.g. stimulation relative to their volumes after P.g. LPS stimulation. Spots (numbered in Fig. 2) were cut from 2-DGE, digested with trypsin and submitted to MALDI-TOF MS for analysis.

Relative volumes of matched spots were determined by PD Quest 7.0 (BioRad).

Apparent mass and pI determined from 2-DGE.

Mass and pI obtained from Swiss-Prot database.

Mascot PMF search parameters are described within the methods. Search results retuned the protein identifications with score >53 and p<0.05.

The peptide masses were submitted to the Swiss-Prot database and to the NCBI database. # indicates the number of peptides matched and (%) reports the percent total sequence coverage.

Sodium/calcium exchanger 2 was not observed on the control gel.

Figure 3.

Representative MALDI-TOF mass spectra of tryptic in-gel digested proteins from spots (a) 10 (Fig. 1b, Table 1) from LPS-treated THP-1 cells, (b) 28 (Fig. 1d, Table 1) from live P.g. –treated THP-1 cells and (c) 29 (Fig. 1d, Table 1) from live P.g.-treated THP-1 cells. The numbers are m/z values (recalibrated using autolysis tryptic peaks as internal standards), the assignments in brackets are peptide sequences whose residue numbers correlate to the protein ID shown in Table 1. Inset shows peptides assigned at (b) m/z 600–1300 and (c) m/z 1000–1140.

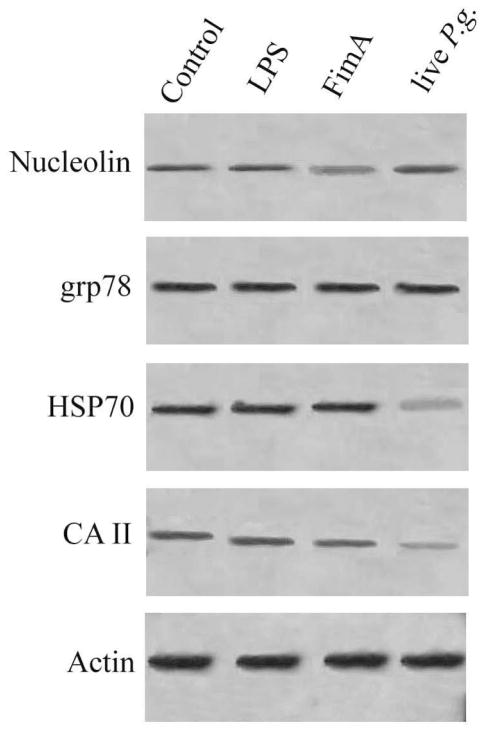

Grp78, HSP70, carbonic anhydrase II and nucleolin were selected for validation by Western blot analysis. These proteins were chosen as representatives to confirm the changes observed in 2-DGE PMF results. As shown in Figure 4, the changes observed by Western blot analysis were similar to the ones reported by 2-DGE-MS.

Figure 4.

Western blot validation of proteins induced in THP-1 cells exposed to P.g LPS, P.g. FimA and live P.g.. Lane 1, Control; lane 2, P.g LPS; lane 3, P.g. Fim A; lane 4, live P.g. Actin was used as control for loading.

Discussion

The primary etiological factor of periodontal disease is the bacterial biofilm, specifically that from P.g., a black-pigmented Gram-negative anaerobic bacterium. P.g. contains various secreted and structural components that can directly cause destruction of periodontal tissues, and also stimulate host cells to activate a wide range of destructive inflammatory responses. These responses are intended to eliminate the microbial challenge but may often cause further tissue damage. The major contributors to P.g.’s virulence are its surface components, including the macromolecular LPS and FimA. These components play important roles in the induction of innate and acquired immune responses, such as the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and of Th1 or Th2 responses in vitro and in vivo in individuals or animals exposed to P. g. (19, 20).

Two Toll-like receptors (TLR-2 and TLR-4) have been identified as signaling receptors through which LPS and FimA exert their biological functions. Zhou et al. (21), and Hirschfeld et al. (22), have shown that P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA signal mainly through TLR-2, resulting in similar patterns of macrophage cytokine expression. P.g. FimA has also been shown to signal through TLR-4 (23).

In this study, P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA stimulation resulted in similar protein profiles in THP-1 cells, although there were subtle differences. These differences may have arisen from the fact that TLR2 associates with other TLRs to form heterodimers, such as TLR1-TLR2 or TLR6-TLR2 (24) or cooperate with TLR4 in the transfer from the innate to the adaptive immunity (25). The formation of heterodimers between TLR2 and another TLR dictates the specificity of ligand recognition, thereby diversifying the possible outcomes of TLR2 activation. Zhou et al. (21) have shown that FimA activates TLR2 possibly as heterodimer. In vivo studies have revealed that, at a relatively low concentration, P. g. FimA is more potent than P. g. LPS in stimulating interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), macrophage inflammatory (MIP-2), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) mRNA expression, while, at a fivefold higher concentration, LPS is more potent than FimA in the induction of TNF-α and iNOS mRNA expression. This difference suggests that different TLR2 agonists may induce differential cell activation (26), and it is possible that the use of different co-receptors or different TLR interfaces involved in pathogen recognition may influence the intensity or quality of the induced signals. As discussed below, we found evidence for this by observation of differences the intensities of protein 2-DGE spots in samples from cells treated with P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA.

Previously, our laboratory has demonstrated that the cytokine profile of human monocytes induced by live P.g. differed substantially from those of its bacterial components LPS and FimA, suggesting that the host immune system senses live P.g. differently and thus launches different immune responses (21). In these experiments, we test at the level of protein expression the hypothesis that unique signaling pathways are differentially induced by live P.g., LPS and FimA. The general consensus is that that many of the effects of bacteria on host immune and inflammatory responses are mediated by changes in gene transcription. However, changes observed at the mRNA level may not necessarily correlate with those seen at the protein levels or in activity, especially when these changes are due to post-translational modifications. To date, only few publications have used large scale proteomics to address the effect of P.g. bacteria and its components on protein expression in monocytes. The present contribution provides the first description of mapping stimulus-specific signaling pathways involved in human monocyte cells exposed to P.g. bacteria and its components using expression proteomics.

Using 2-DGE in combination with MS, we found that P.g. LPS stimulation of THP-1 cells up-regulated their expression of the following proteins compared to control: deoxyribonuclease, actin, carbonic anhydrase 2, alpha enolase, Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein (CAP1), protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), grp78 and HSP70. In contrast, FimA treatment did not result in statistically significant changes to protein levels relative to control. The changes seen after FimA exposure were small and tended to be down-regulatory relative to controls. This suggests that, in terms of the innate immune response, comparing LPS to FimA is no different from comparing LPS to control. Host cells do recognize FimA. Graves et al. (27) have shown that purified FimA protein strongly induced the expression of TNF-α (and MIP-2) but it is not a principal stimulator of the innate host response like LPS. For example, a comparison of mutant P.g. (DPG3) that lacks the fimA gene versus wild-type P.g. showed TNF expression and PMN recruitment to the same extent. Thus, it is not FimA that is involved in the critical role of up-regulating the innate immune response.

Potential Roles of Differentially Expressed Proteins

In the following section, we focus on the potential significance of some of the differentially expressed proteins by considering how they may be involved in the mechanisms underpinning the effects of P.g. and its constituents on infection, inflammation, and immune response.

Heat Shock Protein 70

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a family of highly conserved proteins found in cells. They are the most abundant and ubiquitous soluble intracellular proteins. Numerous studies have shown that HSPs are essential for the survival of the cell when it has been exposed to stressful situations (28). For example, in human blood monocytes, exposure to heat, glucose starvation, or oxidants and physiological oxidative stress during phagocytosis increase the synthesis of HSPs (29). HSP70 has been shown to be an activator of the innate immune system; it is, for example, involved in the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1, IL-6, and IL-12 and in the release of nitric oxide (NO) and C-C chemokines by monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Fincato et al. (30) have shown that monocytic cells express heat-inducible HSP70, and that stimulation with Escherichia coli (E. coli) LPS increases the level of hsp70 mRNA. This may explain the up-regulation of HSP70 in our experiments when THP-1 cells were treated with P.g. LPS. In response to the P.g. LPS stimulated stress, the amount of hsp70 mRNA increased, and that coincided with production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

HSPs can also be found on surfaces of cells, in surface-associated material, and on the outer membrane vesicles produced by bacteria. This localization allows them to interact with the pattern recognition receptors on host cells. It has the ability to bind with high affinity to host cells, elicit a rapid intracellular Ca2+ flux, activate nuclear factor (NF)-κB, and up-regulate the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines in human monocytes (31). The means by which HSP70 signals such activities are similar to activities reported for FimA and live P.g. (21, 23). It utilizes mostly TLR-2 but also TLR-4 receptors. It is thus likely that the competition for the same signaling pathway will result in the inhibition of the potential cytokine-inducing activity of P.g. FimA and live P.g., thereby down-regulating the production of intracellular HSP70.

Protein Disulfide Isomerase

P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA signal through the TLR2 signal transduction pathway, leading to the activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). The activity of the NF-κB transcription factor increases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, or TNF-α (32). These cytokines contribute to the development of symptoms associated with the acute and chronic phases of various immune and regeneration disorders. We observed down-regulation of PDI in response to P.g. FimA stimulation. An explanation for this down-regulation of PDI could be the result of proteolytic degradation of PDI in response to oxidative stress. Typically, immune response to infectious agents involves the activation of effector cells such as phagocytes and lymphocytes, as well as a subsequent production of cytokines and other mediators, mainly reactive oxygen species (ROS). Victor et al. (33) have observed that pathogenic stimulation significantly increases ROS production in peritoneal leukocytes from BALB/c mice with time, peaking at 24 h, thus creating an oxidative stress situation. Gilbert et al. (34) have shown that peroxide generated in activated monocytes causes irreversible modifications in PDI; the modified form is then recognized and degraded by the proteosome complex. In our experiments, the THP-1 monocytes were stimulated for 24 h with P.g. FimA. Since ROS increases with time, the 24-h stimulation period could have resulted in an oxidative stress situation, much more than if the exposure time was shorter. Hence, the lower levels of PDI observed in P.g. FimA induced cells may have been caused by the degradation of PDI in response to oxidative stress.

LPS is a potent inducer of pro-inflammatory mediators such as NO. Macrophage apoptosis induced by LPS is mediated by both NO and TNF production, but they act independently of one another at different times. For example, TNF induces the early apoptotic events (3–6 h), whereas iNOS-dependent apoptotic events occur later (12–24 h) (35). Since our stimulation with P.g. LPS was carried out for 24 h, PDI up-regulation may have been needed to protect against apoptotic cell death (36).

We have previously shown that, after initial response to live P.g., wherein chemokines involved in macrophage and neutrophil recruitment and in the antigen-specific T helper cell type 1 immune response were induced, an extensive set of cytokines (including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) and other mediators increased with prolonged exposure to live P.g. prior to infection. The activity of the NF-κB transcription factor is involved in the production of TNF-α and PDI plays a dominant regulatory role in the NF-κB mediated gene expression pathway, where it acts as a qualitative transcriptional regulator of NF-κB. This is consistent with our observation of PDI being up-regulatory when exposed to live P.g. TNF-α is known to inhibit macrophage apoptosis. (37). During our stimulation with live P.g. over 24 h, PDI up-regulation may have been needed to protect against apoptotic cell death.

Glucose-Regulated Protein 78

Grp78 is induced in the ER compartment by a variety of stresses such as glucose starvation, ER Ca2+ depletion, accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER, and reductive stresses (38) and is therefore involved in mediating ER functions. In response to LPS binding to the cell surface receptor CD14, macrophages release pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1 and NO. Chen et al. (39) have shown that ER Ca2+ stores exert a pivotal role in regulating the production of TNF-α. Furthermore, the release of IL-1β requires depletion of Ca2+ from ER stores, and the production of excess NO can result in depletion of Ca2+ (40). Thus, LPS-induced stress can impinge from all three directions in the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This could result in depletion of the ER Ca2+ stores, which could in turn lead to an elevated grp78 response. Green et al. (41, 42) have examined major ER proteins (ERp99, ERp72, ERp60, PDI and ERp49) and have noticed their stimulation in the presence of E. coli LPS (over 48 h). We have also observed the up-regulation CALR, a Ca2+-binding protein that is involved in the modulation of the host immune response associated with the inflammatory processes for vascular or atherosclerotic lesions, autoimmune diseases, or infections (9, 43). These observations, taken together with the findings of Paver et al. (44) that PDI and grp78 expression increased after LPS stimulation, suggest that these families of ER proteins are co-induced by LPS. This is consistent with our observation of the up-regulation of grp78 and PDI in the P.g. LPS and treated THP-1 cells.

Annexin-1

Annexins are structurally related, calcium-dependent, phospholipid-binding proteins that have been implicated in diverse cellular roles, including control of inflammatory responses. It is also identified as a glucocorticoid-inducible element with inhibitory actions on phospholipase A2 function; it thus prevents the formation of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, and this contributes to its anti-inflammatory properties.

Stimulation of monocytes with LPS results in the release of cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, which is prerequisite to production of other mediators including IL-8 and IL-6. Using an extra-hepatic system, Coupade et al. (45) have shown that IL-6 regulates annexin 1 expression at the transcriptional level. IL-6 is a cytokine that is can be induced through TLR-4 or TLR-2.

Even though there have been several reports that P.g. LPS signals through TLR-2 and not TLR-4, there are still arguments that P.g. LPS also engages TLR-4 due to the presence of multiple lipid A species (46). Darveau et al. (47) have shown that multiple lipid A species are present regardless of the extraction procedure used.

If we make the logical assumption that our P.g. LPS contains multiple lipid A species, then it is possible that this LPS preparation signals through both TLR-2 and TLR-4. We used an efficient purification step for isolating P.g. LPS that is similar to the purification method employed by Darveau et al. (47). However, studies from other laboratories have shown highly purified P.g. LPS preparation are capable of activating through TLR-4. Murine and human TLR-4/MD-2 systems have been shown to be capable of responding to P.g. LPS (47). The major P.g. lipid A species examined in this report was penta-acylated (m/z 1690), and, to the best to our knowledge interacts with TLR-2 and TLR-4. The MALDI-TOF MS characterization of the LPS we used (not shown) also showed a small amount of the tetra-acylated species (m/z 1435 and 1450); it is possible that human TLR-4 can detect tetra-acylated LPS from different species of bacteria. Since the MALDI-TOF MS characterization of lipid A was not quantitative, it is uncertain whether the lipid A species observed at m/z 1,435 and 1,450 were responsible for TLR-4 activation or if minor amounts of other lipid A species (e.g., m/z 1,770) were responsible for activation through the TLR-4 receptor. If so, this would then help interpretation of our observation of the up-regulation of annexin 1 in response to P.g. LPS, since the cytokine IL-6 can only be induced through TLR-4.

Actin

Adherence is a potent stimulus for monocyte differentiation. One of the early events in inflammation is the recruitment of monocytes to the injured area. The interactions that occur here are important for generating signals that induce a functional maturation of recruited blood monocytes, marked by enhanced phagocytosis and cytokine production. Shinji et al. (48) have shown the importance of the actin cytoskeleton in LPS induced TNF-α production in adherent macrophages, speculating that there is a role for actin in LPS signal transduction. While Rosengart et al. (49) have shown that the actin cytoskeleton is essential for LPS-induced signal transduction, specifically the activation of the extacellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK 1/2) of the MAPK family. ERK 1/2 signaling is necessary in monocyte inflammatory cytokine production, especially for TNF-α. Thus, adherence-induced restructuring of the actin cytoskeleton would be critically important for optimal LPS induction of the enhanced TNF-α production that occurs in adherent monocytes. Based on this, Rosengart et al. (49) have proposed that adherence, through integrin-mediated rearrangements in the actin cytoskeleton, organizes and typically keeps selective enzymes such as ERK 1/2 and cofactors, including substrates, unassociated during nonadherence, spatially arranged such that they can respond effectively to an LPS stimulus. These cytoskeletal rearrangements may also enlist the actin architecture as a participant in the LPS-induced signal transduction cascade of adherent cells. Enabling transduction through a restructuring of the actin cytoskeleton appears to explain the enhanced proinflammatory phenotype characteristic of the extravascular adherent monocyte. Hence, this may underlie our observation of actin up-regulation in relation to P.g. LPS stimulation.

Alpha Enolase

Alpha enolase appeared as two separate spots in cells treated with P.g. FimA, probably indicating the presence of post-translational modifications or isoforms. There was only a single alpha enolase spot from cells treated with P.g. LPS. Alpha enolase is a multifunctional protein first characterized by its enzymatic activity in the glycolytic pathway, found in the cytoplasm of cells. Besides its role in glycolysis, alpha enolase is involved in several cellular functions (50, 51).

In response to invading viruses, bacteria and their structural components, cells of the innate immune system release cytokines such as interferons (IFN). Once released, they alter the rates of synthesis and the steady-state levels of many cellular gene transcripts and also regulate the protein products. LPS has been shown to activate members of the MAPK family, including ERK1/2 (52), which is involved in the expression of the alpha-enolase mRNA. The whole process is controlled by the release of Interferon alpha (IFN-α) after stimulation by LPS. IFN-α in turn activates MAPK ERK1/2 and CREB/ATF-1. Both are involved in the expression of alpha enolase. This pathway would help to explain our observation of alpha enolase up-regulation in P.g. LPS-stimulated THP-1 cells.

Watanabe et al. (53) have shown that P.g. adhesion to gingival epithelial cells leads to inactivation of ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Since LPS has shown to stimulate ERK1/2, the inactivation could possibly occur from the stimulation conducted by FimA. P.g. stimulation leads to an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration, activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and inactivation of ERK1/2 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Thus P.g. is capable of selectively activating one MAP kinase pathway and downregulating another. Enterobacterial LPS has been shown to stimulate JNK in a variety of cell type (54). Therefore, one can imagine that, in the incorporation of live P.g., LPS is involved in the activation process while P.g. FimA plays a role in the down-regulation process. Thus it would be likely that stimulation with isolated FimA leads to down-regulation of ERK1/2 and in turn, down-regulation of alpha enolase, as we observed.

Carbonic Anhydrase II

Studies have shown that P.g. LPS and P.g. Fim A are known to induce the production of interleukin (IL)-8 in human monocytes (55, 21). IL-8 is a chemokine produced by macrophages and other cell types such as epithelial cells in response to proinflammotory stimuli. IL-8 attracts neutrophils at the site of inflammation. Coakley et al. (56) have shown that carbonic anhydrase II is involved in inflammatory process. Carbonic anhydrase II acts as a catalyst for maintenance of cellular CO2/HCO3− buffering system. Any variation in pCO2 can affect intracellular pH, thereby influencing IL-8 secretion. Therefore, the up-regulation of carbonic anhydrase II observed with P.g. LPS and P.g. Fim A stimulation is consistent with the observed induction of IL-8 observed in human monocytes.

P. gingivalis proteases are known to degrade IL-1b and IL-6. Similar effects are observed for IL-8. Similarly, carbonic anhydrase II is down-regulated in THP-1 monocytes after stimulation with live P.g. It is possible that this is due to proteases present in live P.g.

Conclusion

Our experiments demonstrate that the proteomics approach holds promise for revealing unique signaling pathways that are differentially induced by live P.g., P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA. The data generated in these experiments using 2-DGE and mass spectrometry provided qualitative comparison of the proteins expressed in response to exposure to live P.g., P.g. LPS and P.g. FimA, and enabled identification of several proteins that are implicated in the effects of the bacteria and its components on the innate immune responses of human monocytes. The variation in protein expression by the stimuli reflects the intrinsic functional difference by the stimuli. This differential modulation of proteins in host cells may well coordinate with their specific roles in triggering host inflammatory/immune responses during P.g. infection.

Comprehensive understanding of host-bacteria interactions is currently incomplete and warrants investigation. The present study deepens our understanding of the P.g.-monocyte interactions contributing to periodontal disease pathogenesis and paves the way for designing new therapeutic approaches aimed at interfering with the pathogenesis pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NIH/NIDCR R01 DE015989 (SA), NIH/NCRR P41RR10888 and S10 RR15942 (CEC), and NIH/NHLBI Contract N01 HV28178 (CEC). The authors thank Qingde Zhou and David H. Perlman for their assistance and advice.

Abbreviations

- ACN

acetonitrile

- CAII

Carbonic Anhydrase II

- CAP1

Adenylyl cyclase-associated protein

- 2DGE

two-dimensional gel electrophoresis

- DHB

2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERK 1/2

extacellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2

- FimA

fimbriae

- GC

gas chromatography

- grp78

glucose regulated protein 78

- HCCA

α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HSP 70

heat shock protein 70

- IDA

information-dependent acquisition

- IEF

isoelectric focusing

- IFN-α

interferon alpha

- IL-6

interleukin-6

- IL-8

interleukin-8, IL-1β, interleukin 1 beta

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IPG

immobilized pH gradient

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- LC

liquid chromatography

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MALDI

matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP-1

monocyte chemoattractant protein 1

- MIP-2

macrophage inflammatory protein 2

- MOIs

multiplicities of infection

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κB

- NO

nitric oxide

- PDI

protein disulfide isomerase

- P.g

Porphyromonas gingivalis

- PMA

phorbol-12-myristate-13 acetate

- PMN

polymorphonuclear neutrophils

- PVDF

polyvinyl difluoride

- QoTOF

quadrupole orthogonal acceleration time-of-flight (mass spectrometer)

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RT

retention time

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SIC

single ion chromatogram

- S/N

signal-to-noise ratio

- TBS

Tris-buffered saline

- TCEP

Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TIC

total ion chromatogram

- TLR

Toll-like receptors

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TOF

time-of-flight (mass spectrometer)

References

- 1.Craig RG, Yip JK, So MK, Boylan RJ, Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1007–1016. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.7.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakagawa I, Amano A, Kimura RK, Nakamura T, Kawabata S, Hamada S. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:1909–1914. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.5.1909-1914.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogawa T, Uchida H. Immunol Med Microbiol. 1995;11:197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1995.tb00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin M, Katz J, Vogel SN, Michalek SM. J Immunol. 2001;167:5278–5285. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fine DH, Mendieta C, Barnett ML, Furgang D, Naini A, Vincent JW. J Periodontol. 1992;63:897–901. doi: 10.1902/jop.1992.63.11.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogawa T, Asai Y, Hashimoto M, Uchida H. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:2543–2550. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200209)32:9<2543::AID-IMMU2543>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murakami Y, Hanazawa S, Watanabe A, Naganuma K, Iwasaka H, Kawakami K, Kitano S. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5242–5246. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5242-5246.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirose K, Isogai E, Ueda I. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44:17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Q, Amar S. Infect Immun. 2006;74:1204–1214. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.2.1204-1214.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gygi SP, Rochon Y, Franza BR, Aebersold R. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1720–1730. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis TS, Hunt JB, Aveline LD, Jonscher KR, Louie DF, Yeh JM, Nahreini TS, Resing KA, Ahn NG. Molecular Cell. 2001;6:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JY, Sojar HT, Amano A, Genco RJ. Protein Expr Purif. 1995;6:496–500. doi: 10.1006/prep.1995.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manthey CL, Vogel SN. J Endotoxin Res. 1994;1:84–88. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shevchenko A, Wilm M, Vorm O, Mann M. Anal Chem. 1996;68:850–858. doi: 10.1021/ac950914h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karas M, Hillenkamp F. Anal Chem. 1988;60:2299–2306. doi: 10.1021/ac00171a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen SL, Chait BT. Anal Chem. 1996;68:31–37. doi: 10.1021/ac9507956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kussmann M, Lassing U, Sturmer CAO, Przybylski M, Roepstorff P. J Mass Spectrom. 1997;32:483–493. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9888(199705)32:5<483::AID-JMS502>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pappin DJ, Hojrup P, Bleasby AJ. Curr Biol. 1993;3:327–332. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90195-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jotwani R, Cutler CW. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1725–1732. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1725-1732.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jotwani R, Pulendran B, Agrawal S, Cutler CW. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2980–2986. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Q, Desta T, Fenton M, Graves DT, Amar S. Infec Immun. 2005;73:935–943. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.935-943.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hirschfeld M, Weis JJ, Toshchakov V, Salkowski CA, Cody MJ, Ward DC, Qureshi N, Michalek SM, Vogel SN. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1477–1482. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1477-1482.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hajishengallis G, Martin M, Sojar HT, Sharma A, Schifferle RE, DeNardin E, Russell MW, Genco RJ. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2002;9:403–411. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.2.403-411.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ozinsky A, Underhill DM, Fontenot JD, Hajjar AM, Smith KD, Wilson CB, Schroeder L, Aderem A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13766–13771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250476497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laflamme N, Echchannaoui H, Landmann R, Rivest S. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1127–1138. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajishengallis G, Martin M, Schifferle RE, Genco RJ. Infect Immun. 2002;70:6658–6664. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.12.6658-6664.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Graves DT, Naguib G, Lu H, Desta T, Amar S. J Endo Res. 2005;11:13–18. doi: 10.1179/096805105225006722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaattela M. Ann Med. 1999;31:261–271. doi: 10.3109/07853899908995889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barreto A, Gonzalez JM, Kabingu E, Asea A, Fiorentino S. Cell Immunol. 2003;222:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(03)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fincato G, Polentarutti N, Sica A, Mantovani A, Colotta F. Blood. 1991;77:579–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asea A, Rehli M, Kabingu E, Boch JA, Baré O, Auron PE, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15028–15034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200497200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghosh S, Karin M. Cell. 2002;109:S81–S96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Victor VM, De la Fuente M. Physiol Res. 2003;52:789–796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gilbert HF. Methods Enzymol. 1998;290:26–50. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(98)90005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xaus J, Comalada M, Valledor AF, Lloberas J, López-Soriano F, Argilés JM, Bogdan C, Celada A. Blood. 2000;95:3823–3831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paver JL, Freedman RB, Parkhouse RME. FEBS. 1989;242:357–362. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mangan DF, Welch GR, Wahl SM. J Immunol. 1991;146:1541–1546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee AS. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:504–510. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(01)01908-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Y, Lin-Shiau S. J Biomed Sci. 2000;7:122–127. doi: 10.1007/BF02256618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oyadomari S, Takeda K, Takiguchi M, Gotoh T, Matsumoto M, Wada I, Akira S, Araki E, Mori M. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:10845–10850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191207498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis M, Mazarella RA, Green M. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;245:389–403. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(86)90230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewis M, Mazzarella RA, Green M. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3050–3057. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ghebrehiwet B, Peerschke EI. Mol Immunol. 2004;41:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paver JL, Freedman RB, Parkhouse RME. FEBS. 1989;242:357–362. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)80501-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Coupade C, Ajuebor MN, Russo-Marie F, Perretti M, Solito E. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1435–1443. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62530-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Parente L, Solito E. Inflamm Res. 2004;53:125–132. doi: 10.1007/s00011-003-1235-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Darveau RP, Pham TT, Lemley K, Reife RA, Bainbridge BW, Coats SR, Howald WN, Way SS, Hajjar AM. Infec Immun. 2004;72:5041–5051. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5041-5051.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shinji H, Akagawa KS, Yoshida T. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;54:336–342. doi: 10.1002/jlb.54.4.336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosengart MR, Arbabi S, Bauer GJ, Garcia I, Jelacic S, Maier RV. Shock. 2002;17:109–113. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200202000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pancholi V, Fischetti VA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14503–14515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miles LA, Dahlberg CM, Plescia J, Felez J, Kato K, Plowt EF. Biochemistry. 1991;30:1682–1691. doi: 10.1021/bi00220a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.van der Bruggen T, Nijenhuis S, van Raaij E, Verhoef J, van Asbeck BS. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3824–3829. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3824-3829.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watanabe K, Yilmaz Z, Nakhjiri SF, Belton CM, Lamonti RJ. Infec Immun. 2001;69:6731–6737. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.11.6731-6737.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cario E, Rosenberg IM, Brandwein SL, Beck PL, Reinecker HC, Podolsky DK. J Immunol. 2000;164:966–972. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nassar H, Chou HH, Khlgatian M, Gibson FC, III, Van Dyke TE, Genco CA. Infect Immun. 2002;70:268–276. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.1.268-276.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coakley RJ, Taggart C, Greene C, McElvaney NG, O’Neill SJ. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:603–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roepstorff P, Fohlman J. Biomed Mass Spectrom. 1984;11:601. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200111109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Biemann K. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:977–1010. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.004553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]