Abstract

AIM: To evaluate outcomes of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) therapy for early hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and identify survival- and recurrence-related factors.

METHODS: Consecutive patients diagnosed with early HCC by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (single nodule of ≤ 5 cm, or multi- (up to 3) nodules of ≤ 3 cm each) and who underwent RFA treatment with curative intent between January 2010 and August 2011 at the Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil were enrolled in the study. RFA of the liver tumors (with 1.0 cm ablative margin) was carried out under CT-fluoro scan and ultrasonic image guidance of the percutaneous ablation probes. Procedure-related complications were recorded. At 1-mo post-RFA and 3-mo intervals thereafter, CT and MRI were performed to assess outcomes of complete response (absence of enhancing tissue at the tumor site) or incomplete response (enhancing tissue remaining at the tumor site). Overall survival and disease-free survival rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log rank test or simple Cox regression. The effect of risk factors on survival was assessed by the Cox proportional hazard model.

RESULTS: A total of 38 RFA sessions were performed during the study period on 34 patients (age in years: mean, 63 and range, 49-84). The mean follow-up time was 22 mo (range, 1-33). The study population showed predominance of male sex (76%), less severe liver disease (Child-Pugh A, n = 26; Child-Pugh B, n = 8), and single tumor (65%). The maximum tumor diameters ranged from 10 to 50 mm (median, 26 mm). The initial (immediately post-procedure) rate of RFA-induced complete tumor necrosis was 90%. The probability of achieving complete response was significantly greater in patients with a single nodule (vs patients with multi-nodules, P = 0.04). Two patients experienced major complications, including acute pulmonary edema (resolved with intervention) and intestinal perforation (led to death). The 1- and 2-year overall survival rates were 82% and 71%, respectively. Sex, tumor size, initial response, and recurrence status influenced survival, but did not reach the threshold of statistical significance. Child-Pugh class and the model for end-stage liver disease score were identified as predictors of survival by simple Cox regression, but only Child-Pugh class showed a statistically significant association to survival in multiple Cox regression analysis (HR = 15; 95%CI: 3-76 mo; P = 0.001). The 1- and 2-year cumulative disease-free survival rates were 65% and 36%, respectively.

CONCLUSION: RFA is an effective therapy for local tumor control of early HCC, and patients with preserved liver function are the best candidates.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Radiofrequency ablation, Overall survival, Disease-free survival

Core tip: Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is widely recognized as an effective therapy for early stage hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in patients who are not suitable candidates for surgical resection, such as those with decompensated liver function or portal hypertension. Reports from Brazil of clinical experience with RFA management of HCC are rare. This study evaluated 34 consecutive patients with early HCC treated with RFA at a single Brazilian hospital. RFA was efficacious for promoting local tumor control and positive outcome was related to preserved liver function. Careful evaluation of liver function may help to identify the best candidates for this procedure.

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most frequently diagnosed primary hepatic malignancy, with the majority of cases occurring in patients with liver cirrhosis[1,2]. The increased practice of ultrasonography (US)-based surveillance of high-risk patients, such as those with chronic liver disease, has promoted the rates of HCC diagnosis at the early stage when therapeutic intervention is more likely to be effective and less extensive. While surgical resection remains the preferred curative treatment method, patients with decompensated liver function or portal hypertension are contraindicated for this procedure and may require liver transplantation; however, the substantially complicated nature of organ transplantation and lack of donors has led researchers to seek alternative methods for local tumor control, and percutaneous ablation therapy has emerged as a particularly promising treatment for such patients[3].

Percutaneous tumor ablation has been shown to promote tumor necrosis and preserve liver function[3,4]. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is currently considered the most effective modality of percutaneous ablation therapy, with demonstrated efficacy and safety profiles for early HCC cases of both single lesion (1 nodule, ≤ 50 mm) and multi-lesion (up to 3 nodules, ≤ 30 mm each)[3,4]. RFA is a physical thermal ablation technique by which energy is introduced directly into the tumor tissue through an active electrode. The electric current is converted into heat in a closed circuit and the ionic agitation of molecules caused by intracellular movement of alternating electrical current at the needle tip results in friction-generated heat; temperatures around and above 60 °C cause coagulation necrosis[4].

Meta-analyses of the randomized controlled trials carried out to investigate the efficacies and outcomes of various tumor ablation techniques have shown RFA to be superior to ethanol injection for achieving complete tumor ablation and in survival rates[5,6]. A recent meta-analysis of studies investigating the efficaciousness of RFA vs hepatic resection also indicated that the two procedures produced similar short-term therapeutic efficacies in early HCC cases[7]. The accumulated evidence of RFA efficacy has promoted its popularity among physicians for treating unresectable early HCC.

The majority of studies on RFA outcomes in HCC patients have been conducted with Asian and European populations[8-11]. Few reports of clinical experience with this particular interventional technique have been reported for early HCC patients in Latin America. The study reported herein was carried out to assess the outcome of potentially curative RFA therapy in patients with early HCC treated at a large metropolitan hospital in Brazil and to identify the related risk factors for survival and tumor recurrence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and patient selection

This study was designed as a single-center retrospective analysis and was carried out with pre-approval by the local institutional review board (Registration ID: 368/12; Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo (ICESP), Brazil) according to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

The hospital’s prospective database was searched for patients diagnosed with early HCC who underwent RFA treatment with curative intent between January 2010 and August 2011. Patients who were subject to RFA without curative intent (as recommended by multidisciplinary team evaluation) were excluded from analysis, regardless of whether a clinically effective outcome had been achieved. However, patients who had been awaiting liver transplantation and received RFA as bridge therapy were included in the study.

HCC diagnosis and staging

Prior to the RFA treatment, all patients had been evaluated by imaging analysis (including US, contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or chest CT), physical examination, and laboratory testing. The Child-Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scoring systems were applied to determine liver function status. HCC was diagnosed according to dynamic CT or MRI findings showing hyperattenuation in the arterial phase with washout in the portal venous phase[12,13]. In cases with inconclusive imaging findings, tumor biopsy was performed to confirm the HCC diagnosis.

For all patients, the RFA treatment was selected after consideration of the tumor parameters (i.e., site, size, and number), the functional reserve of the liver, and the general health status. In particular, the following criteria were applied to determine a patient’s candidacy for RFA: (1) ineligibility for or refusal of surgical resection; (2) US-detected tumor; (3) a single nodule ≤ 50 mm in diameter, or up to three nodules with a maximum diameter of 30 mm each; (4) Child-Pugh A or B cirrhosis; and (5) international normalized ratio of < 1.6 and platelet count of > 50 × 109/L. The following conditions were considered contraindications for RFA: (1) hepatic hilum proximal to the tumor; (2) abundant ascites; (3) decompensated encephalopathy; and (4) extrahepatic tumor spread and/or macrovascular invasion.

RFA

At ICESP, the RFA routine is standardized, and all procedures were performed by one of three trained physicians (one having record of at least 5-years of experience with percutaneous ablation therapy) using the Cool-Tip 200-W RF generator (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States). The procedure was performed on an in-patient basis with general endotracheal anesthesia or conscious sedation, depending on the target location and anticipated complexity. Prior to needle insertion, the point of entry was planned to ensure a safe trajectory and end position. CT-fluoro scan and US image guidance was used to precisely place the ablation probes percutaneously within the tumor. The tumor size, location, and geometry were considered when selecting whether a single 17-gauge or triple cluster 17-gauge needle electrode will be applied in the RFA procedure. The tumor ablation was carried out in overlapping sessions, with the intent of ablating the entire tumor along with a 1.0 cm ablative margin.

Immediately after the procedure, a contrast-enhanced CT was performed in the interventional suite and detection of residual tumor tissue necessitated an additional needle insertion and ablation routine.

Follow-up

The efficacy of RFA was evaluated at one month after the procedure. CT or MRI imaging analysis was carried out and the response to RFA was classified as complete response (absence of enhancing tissue at the tumor site) or incomplete response (enhancing tissue observed at the tumor site). Patients showing incomplete response were given an additional RFA procedure. After achievement of complete response, patients were followed-up at 3-mo intervals, until April 2013. The follow-up evaluations included clinical testing (including liver function testing) and CT or MRI. Tumor recurrence was diagnosed upon imaging detection of an enhancing area within or at the periphery of the ablated lesion. The recurrence was defined as distant if one or more of the detected tumor(s) were > 1 cm beyond the primary site. Patients with recurring HCC tumors were treated with additional RFA, if the same initial criteria for RFA candidacy remained satisfied. For those patients with recurrent HCC that showed contraindications to additional RFA, alternative therapies (such as transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) or sorafenib) were considered and applied.

All major complications that occurred during the follow-up period were recorded. Major complications were defined as complications resulting in hospital admission for interventional therapy, unplanned increase in the routine level of medical care, prolonged hospitalization, permanent adverse sequelae, or death.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data were expressed as median and range. The Lausen (1994) method was used to identify cutoff points of tumor size and MELD score necessary to maximize the subsequent log rank statistical analysis[14]. Fisher’s exact test was carried out to identify variables associated with initial complete response.

Overall survival was defined as the interval between treatment and death or date of last follow-up. Probability of disease-free survival was defined as the interval between treatment and the date of local or distant HCC recurrence. Survival rates were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log rank or simple Cox regression analyses. The effect of risk factors on survival was assessed by the Cox proportional hazard model, according to the calculated hazard risk (HR) and 95%CI. All statistical analyses were performed by the R statistical computing package (version 2.15.2; The R Project for Statistical Computing). A P-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic, clinical and RFA treatment characteristics of early HCC patients

Of the total 395 patients with HCC who were evaluated for potential clinical management at ICESP during the 20-mo study period, 38 (12%) were treated with RFA. Four patients that received RFA without curative perspective were excluded from analysis. The baseline characteristics of the 34 RFA-treated patients are shown in Table 1. This patient population showed predominance of males, low-grade liver dysfunction (Child-Pugh A), single tumor status, and larger tumor size (only 17% had tumors ≤ 2 cm).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 34 patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma treated with radio frequency ablation n (%)

| Characteristics | No. of patients (n = 34) |

| Sex, male/female | 26/8 |

| Age in years median, range | 63, 49-84 |

| Etiology, | |

| HCV | 24 (70) |

| HBV | 1 (3) |

| Alcohol | 6 (18) |

| Others | 3 (9) |

| Child-Pugh class | |

| A | 26 (76) |

| B | 8 (24) |

| MELD points median, range | 9, 6-16 |

| Cutpoint by Lausen method | 11 |

| Portal hypertension, n (%) | 27 (79) |

| ECOG-PST, 0/1 % | 85/15 |

| BCLC stage, 0/A % | 18/82 |

| Alpha-fetoprotein in ng/mL median, range | 10.7, 1.4-12.7 |

| Tumor size in mm, median, range | 26, 10-50 |

| Cutpoint by Lausen method | 35 |

| Tumor stage, n (%) | |

| Single | 22 (65) |

| ≤ 20 mm | 6 |

| 21-30 mm | 8 |

| > 30 mm | 8 |

| Multinodular | 12 (35) |

| Initial response (n = 32) | |

| Complete | 29 (90) |

| Partial | 3 (10) |

| Recurrence (n = 32) | |

| No | 17 (53) |

| Yes | 15 (47) |

| Local tumor recurrence | 6 |

| Distant recurrence | 9 |

HCV: Hepatitis C Virus; HBV: Hepatitis B Virus; MELD: Model for end-stage liver disease.

A total of 38 RFA sessions were performed in the 34 patients. Only three patients showed incomplete initial response, but complete response was achieved in all after additional RFA sessions (2 sessions, n = 2; 3 RFA sessions, n = 1). The median follow-up period was 22 mo (range, 1-33) for all patients; two patients were lost to follow-up.

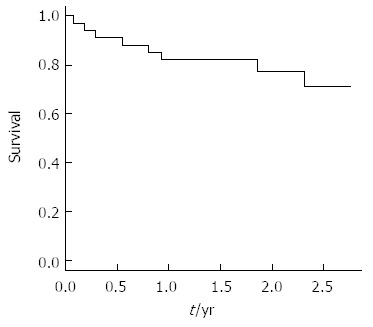

Overall survival rates of RFA and related factors

The 1- and 2-year overall survival rates were 82% and 71%, respectively (Figure 1). No deaths occurred among the female patients during the follow-up period. Overall survival time was significantly higher for patients with tumors ≤ 35 mm in diameter (3 years vs > 35 mm: 2 years, P = 0.08). All patients that achieved complete response had a single tumor, while 27% of the patients with multinodular HCC never achieved complete response (i.e., partial response); the probability of achieving complete tumor ablation was significantly greater in patients with a single nodule (vs multiple tumors, P = 0.04).

Figure 1.

Overall survival of the 34 patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma treated with radio frequency ablation.

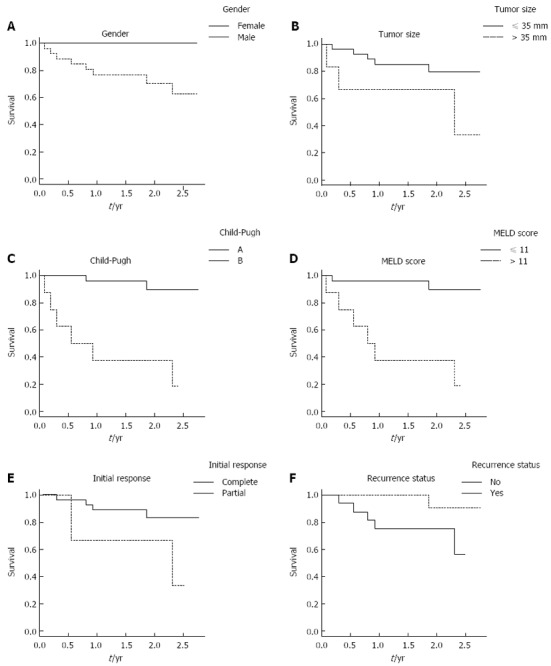

Overall survival rate was higher in patients with complete response (HR = 0.22, 95%CI: 0.04-1.22), but the difference from patients with incomplete response did not reach the threshold for statistical significance (P = 0.83). Preserved liver function was associated with a significantly better overall survival time, as shown by patients with MELD score ≤ 11 (HR = 14.00, 95%CI: 2.8-70.0 mo; vs ≥ 12, P = 0.001) and patients classified as Child-Pugh A (HR = 15.00, 95%CI: 3.0-76.0 mo vs Child-Pugh B, P = 0.001). Patients with recurrence during follow-up showed a trend towards better survival, but this result may reflect the different (longer) follow-up times of certain patients (Figure 2). In multiple Cox regression analysis, only the Child-Pugh class was found to be associated with survival at a statistically significant level.

Figure 2.

Cumulative survival rates of hepatocellular carcinoma patients following radiofrequency ablation treatment. Comparisons are presented between the following patient sub-groups. A: Male and female; B: Tumor size of ≤ 35 mm and > 35 mm; C: Child-Pugh A and B; D: Model for end-stage liver disease score ≤ 11 and > 11; E: Complete and partial initial response; F: With tumor recurrence and without tumor recurrence.

Outcomes of RFA bridge treatment in patients with substantial liver dysfunction

Sixteen of the RFA-treated patients were on the liver transplant waiting list in the beginning of their follow-up period. Four of those patients received orthotopic liver, and the median time to transplant was 12 mo. Five of the patients who did not receive a donor-match died from liver failure, and all showed no signs of HCC progression. At the end of follow-up, seven patients remained on the liver transplant list and met the Milan criteria. Explant analysis of the four transplanted patients showed that although the main nodule was completely necrotic in two of the cases and partially necrotic in the other two cases, small HCC foci (nodules < 10 mm) were present in all of the explanted liver specimens.

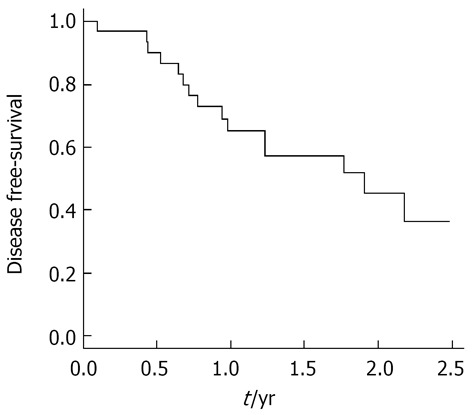

Disease-free survival rates of RFA and factors related to recurrence

At the end of follow-up, tumor recurrence had been detected in 15 (47%) of the total 32 patients. The 1- and 2-year cumulative disease-free survival rates were 65% and 36%, respectively (Figure 3). Tumor recurrence during follow-up was influenced by survival; log rank test indicated that patients with better survival rates (Child-Pugh A, MELD ≤ 11, and female) were at risk for recurrence.

Figure 3.

Cumulative disease-free survival of the 34 patients with early hepatocellular carcinoma treated with radio frequency ablation.

Both local recurrence (n = 6) and distant recurrence (n = 9) occurred. Among the patients that experienced distal recurrence, three showed macroscopic vascular invasion at the time of recurrence detection and one experienced nodal recurrence. Treatment for recurrence included RFA (n = 6), percutaneous ethanol injection (n = 2), TACE (n = 5), and sorafenib (n = 2).

Major complications of RFA

Two patients experienced major complications following the RFA sessions. One patient developed acute pulmonary edema and was transferred to the intensive care unit; the patient fully recovered and was discharged to home without further incident occurring during the remaining follow-up. Another patient experienced intestinal perforation and died 31 d after the RFA procedure.

Of the total 12 patients (34%) that died during the follow-up period, only one death was attributed to HCC progression. The majority of deaths (50%) were related to complications of underlying cirrhosis and liver failure. Three deaths were attributed to other causes unrelated to tumor, liver failure, or the RFA treatment. None of the patients that survived to the end of follow-up presented any clinical signs of worsening liver function.

DISCUSSION

In the past two decades, RFA has become recognized worldwide as an efficacious and safe treatment modality for patients with early HCC[12,13]. In Brazil, more than one-third of newly diagnosed HCC cases are classified as early stage[2], and clinicians face the same clinical challenges for treating these types of patients with concomitant portal hypertension or decompensated liver function (contraindicators for surgical resection)[3]. To expand our knowledge of RFA application and outcome in Brazil, this study evaluated the initial (immediate post-procedural) and short-term (1-2 year follow-up) clinical experience with RFA in a single treatment center with experienced staff. The 38 RFA procedures performed with curative intent on a total of 34 patients with early HCC showed high anti-tumor effect, providing complete response in 90% of the patients. Moreover, the overall survival rate was found to be significantly associated with liver function in these patients.

After selection of tumor variables (number and size), our results showed a great discrepancy in terms of overall survival after RFA depending on liver function. Specifically, the 1-year survival rates for patients with Child-Pugh A and B score were 96% and 37%, respectively. Similar findings were reported by other groups examining clinical efficacy of RFA[15-17]. Because most HCCs arise in the context of liver cirrhosis, the established liver impairment may already represent a general poor prognosis for these patients. Indeed, for Child-Pugh C patients, HCC treatment has no effect on outcome[12,13]. For Child-Pugh B patients, however, HCC treatment can be beneficial, but the outcome is not consistent. Asymptomatic HCC patients with minor laboratory changes and without decompensated cirrhosis are categorized within the same group as patients with ascites, encephalopathy, and/or important coagulopathy. Recent recommendations for TACE treatment candidacy emphasize careful selection from among those patients with Child-Pugh B[18]. The data from the current study also indicate that liver function is an important consideration for RFA candidacy. Child-Pugh B patients comprised 24% of the study population and most of these patients had MELD scores > 11 as well as a previous episode of ascites or encephalopathy which was compensated before the RFA treatment (data not shown).

RFA was very successful in promoting tumor control in the current study population, in general. Achievement of complete response was detected in the initial evaluation for all patients with single nodule HCC. Achievement of initial complete response after RFA has been reported as an important predictor of survival, due to its association with significant improvement in disease outcome[15,19]. The impact of extensive tumor necrosis on survival has also been reported for TACE[20], and researchers have considered features of this alternative treatment modality in hopes of developing improved strategies for RFA. Multiple electrode insertion was proposed to facilitate generation of a sufficient safety margin, and iterative RFA was shown to promote achievement of complete and durable ablation[9]. TACE has also been applied as an adjunct therapy to RFA and improves the treatment-induced tumor necrosis. Occlusion of arterial flow during RFA significantly enlarges the zone of coagulation, which may underlie the improved effects on tumor control that are achieved when RFA is used in combination with transarterial therapies, such as TACE. Indeed, supplementing RFA with TACE has been shown to improve survival in some HCC patients, but the precise benefit of this association must be validated[21-23].

Recurrence of tumors treated with RFA occurred in 47% of the patients in the current study. Despite imaging analysis detecting no viable neoplastic tissue at post-procedural and follow-up exams, residual nests of tumor cells contributed to local tumor recurrence in 40% of these cases. The cases of distant recurrences (60% of recurrences) was not surprising due to the multicentric nature of HCC in cirrhosis. Recurrent HCC is not uncommon after RFA nor is it specific to this modality of therapy. Even patients treated with hepatic resection show recurrence rates > 70% at five years after the surgical therapy[24,25]. Unfortunately, no adjuvant therapy has demonstrated a significant improvement in disease-free rates after potentially curative therapies (such as RFA) for early HCC either.

Most of the published data on RFA effectiveness has come from studies conducted with Eastern cohorts of patients and generalization to Western patients may not be feasible because of the known etiologic differences of these populations[26,27]. The largest study to date on RFA outcome demonstrated that etiology of liver disease is an important predictor of long-term survival and distant intrahepatic recurrence, and identified a role for chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) in patient survival[10]. In another study, patients with HCV-related cirrhosis who achieved sustained virological response to antiviral therapy were shown to have a substantially lower rate of HCC recurrence and accompanying higher survival rate[9]. In the current study, up to 70% of the patient cohort were HCV-positive (data not shown) and this may have played a role in the high recurrence rate.

RFA is a well-established bridge therapy for patients awaiting liver transplant. The results from explant analysis of the transplanted patients supported the finding that RFA is very efficacious in promoting tumor necrosis; the treated lesions remained necrotic in all cases. However, very small (< 1 cm) HCC lesions were found in all explant specimens. Thus, RFA appears to be a good choice for bridge therapy of patients with compensated liver function while awaiting donor liver to become available for transplantation[28]; those patients with decompensated liver function, however, may not be suitable candidates for RFA, and liver transplantation should remain the treatment of choice. In our hospital, the average wait time for a donor liver was approximately 12 mo[2]; living-donor transplant may also be an excellent curative therapy and should be explored as a feasible alternative for some HCC patients, such as those not suited to surgical resection or RFA.

One RFA-related death that of gastrointestinal perforation, occurred in the current study’s cohort. Risk of this type of procedure-related complication is increased when the target nodule is located adjacent to the intestine, and the risk is even higher when the patient has a previous history of gastrointestinal surgery. The reported frequency of gastrointestinal perforation in RFA is 0.3% per treatment[29]. Our patient had no history of gastrointestinal surgery and we performed an intraperitoneal infusion technique, by which 500-1000 mL of 5% glucose solution was injected before and during the ablation routine for the purpose of creating space between the lesion and the intestine. The RFA procedure itself was uncomplicated and the patient was discharged to home afterwards. Ten days later, the patient returned to clinic with acute abdominal pain and immediately underwent laparotomy and colostomy. Nonetheless, the patient died 31 d after the RFA procedure.

The current study has several limitations inherent to its study design that must be considered when interpreting its results. While the small sample size reflected the normal volume for this procedure in a reference HCC center in Brazil, it may have been the reason why no significant differences were observed for some of the well-known predictors of survival and recurrence. Furthermore, the current study’s findings were gained from a single-center cohort and cannot be compared to clinical experiences from other treatment centers, due to heterogeneity of selection and patient management, physicians’ expertise, indication of additional treatments, and the institution’s volume of care. Liver transplantation is considered the optimal treatment for early HCC patients with decompensated liver function, and these patients are not good candidates for the alternative minimally invasive therapies. Inclusion of patients with more advanced liver dysfunction (Child-Pugh B patients) in the current study’s cohort may have compromised the overall survival rate. However, this cohort composition was considered an accurate reflection of the actual profile of patients seeking HCC treatment, and the results may help to refine selection criteria for RFA candidates in our hospital in the future.

In summary, RFA was a safe and effective therapy to achieve local tumor control of early HCC in Brazilian patients. The best candidates for RFA were patients with early HCC and well preserved liver function. Careful follow-up with imaging analysis should be conducted after RFA, as the rate of recurrence remains high. Yet, most cases of recurrence can be effectively treated with additional RFA or other standard therapies. Finally, RFA ablation was shown to be an effective bridge therapy during the wait for a donor liver, but mainly benefited patients with well compensated liver function.

COMMENTS

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a frequent complication of chronic liver disease and is the main cause of death in patients with compensated liver cirrhosis. Prospective surveillance of cirrhotic patients has improved the diagnosis rates of HCC in early stage, when patients are candidates for potentially curative therapies. In this scenario, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has emerged as a promising alternative therapy.

Research frontiers

RFA is the standard of care for patients with early HCC who are not candidates for surgical resection. RFA is considered safe and effective due to its demonstrated ability to promote tumor necrosis without deterioration of liver function. This study identifies risk factors for survival and disease recurrence following RFA treatment, and the results are expected to improve patient selection for this procedure.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The publically available literature includes few reports of clinical experience and analyses of RFA in HCC patients from Brazil and Latin America. Selection and patient management, physicians’ expertise, indication of additional treatments, and the institution’s volume of care can be institution specific and may influence RFA outcome. This study of a Brazilian patient cohort from a hospital with clinical expertise in RFA confirms the importance of careful liver function evaluation when considering a patient’s candidacy for RFA.

Applications

RFA is a very effective therapy to promote local tumor control. Patients with well-preserved liver function were shown to have better survival rates following RFA treatment of HCC. For patients classified as Child-Pugh B, liver transplantation should remain the first choice for therapy.

Terminology

RFA is a physical thermal ablation technique that introduces energy directly into target tissue (such as a tumor lesion) through an active electrode. HCC is a primary malignant tumor that frequently occurs in patients with chronic liver disease. Decompensated liver function occurs when the liver can no longer function normally. Overall survival denoted the chance of staying alive after the treatment for HCC. Tumor recurrence was defined as the return of HCC after treatment and after a period of time during which the cancer could not be detected by routine imaging analysis.

Peer review

This study analyzed data from Brazilian patients with early HCC who underwent RFA with curative intent. A rate of 90% complete tumor necrosis was obtained at initial (immediate post-procedural) evaluation. The 1- and 2-year overall survival rates were 82% and 71%, respectively. Child-Pugh class was the only independent predictor for survival following RFA. The results of this study agree with those from similar studies in ethnically and geographically different cohorts that have been previously published, and provide novel insights into the unique clinical experience of a Latin America-based population. Although this was a preliminary study and used only a small amount of cases, the results may be useful to treating physicians in selecting candidates for RFA treatment.

Footnotes

Supported by Alves de Queiroz Family Fund for Research

P- Reviewers: Assy N, Guo XZ, Liu P, Zeng Z S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

References

- 1.Bosch FX, Ribes J, Díaz M, Cléries R. Primary liver cancer: worldwide incidence and trends. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:S5–S16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kikuchi L, Chagas AL, Alencar RS, Paranaguá-Vezozzo DC, Carrilho FJ. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of hepatocellular carcinoma in Brazil. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:445–449. doi: 10.3851/IMP2602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245–1255. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lencioni R. Loco-regional treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;52:762–773. doi: 10.1002/hep.23725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orlando A, Leandro G, Olivo M, Andriulli A, Cottone M. Radiofrequency thermal ablation vs. percutaneous ethanol injection for small hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:514–524. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouza C, López-Cuadrado T, Alcázar R, Saz-Parkinson Z, Amate JM. Meta-analysis of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation versus ethanol injection in hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2009;9:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-9-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan C, Liu M, Zhang Z, Ma K, Bie P. Radiofrequency ablation versus hepatic resection for the treatment of early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma meeting Milan criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2013;11:190. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-11-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan K, Chen MH, Yang W, Wang YB, Gao W, Hao CY, Xing BC, Huang XF. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term outcome and prognostic factors. Eur J Radiol. 2008;67:336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.N'Kontchou G, Mahamoudi A, Aout M, Ganne-Carrié N, Grando V, Coderc E, Vicaut E, Trinchet JC, Sellier N, Beaugrand M, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term results and prognostic factors in 235 Western patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2009;50:1475–1483. doi: 10.1002/hep.23181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shiina S, Tateishi R, Arano T, Uchino K, Enooku K, Nakagawa H, Asaoka Y, Sato T, Masuzaki R, Kondo Y, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma: 10-year outcome and prognostic factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:569–577; quiz 578. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pompili M, Saviano A, de Matthaeis N, Cucchetti A, Ardito F, Federico B, Brunello F, Pinna AD, Giorgio A, Giulini SM, et al. Long-term effectiveness of resection and radiofrequency ablation for single hepatocellular carcinoma ≤ 3 cm. Results of a multicenter Italian survey. J Hepatol. 2013;59:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Association For The Study Of The Liver; European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lausen B, Sauerbrei W, Schumacher M. Classification and regression trees (CART) used for the exploration of prognostic factors measured on different scales. In: Dirschedl P and Ostermann R., editor. Computational statistics. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag; 1994. pp. 483–496. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sala M, Llovet JM, Vilana R, Bianchi L, Solé M, Ayuso C, Brú C, Bruix J. Initial response to percutaneous ablation predicts survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2004;40:1352–1360. doi: 10.1002/hep.20465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tateishi R, Shiina S, Teratani T, Obi S, Sato S, Koike Y, Fujishima T, Yoshida H, Kawabe T, Omata M. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma. An analysis of 1000 cases. Cancer. 2005;103:1201–1209. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lencioni R, Cioni D, Crocetti L, Franchini C, Pina CD, Lera J, Bartolozzi C. Early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: long-term results of percutaneous image-guided radiofrequency ablation. Radiology. 2005;234:961–967. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2343040350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piscaglia F, Terzi E, Cucchetti A, Trimarchi C, Granito A, Leoni S, Marinelli S, Pini P, Bolondi L. Treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma in Child-Pugh B patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:852–858. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi S, Kudo M, Chung H, Inoue T, Ishikawa E, Kitai S, Tatsumi C, Ueda T, Minami Y, Ueshima K, et al. Initial treatment response is essential to improve survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent curative radiofrequency ablation therapy. Oncology. 2007;72 Suppl 1:98–103. doi: 10.1159/000111714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gillmore R, Stuart S, Kirkwood A, Hameeduddin A, Woodward N, Burroughs AK, Meyer T. EASL and mRECIST responses are independent prognostic factors for survival in hepatocellular cancer patients treated with transarterial embolization. J Hepatol. 2011;55:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim JH, Won HJ, Shin YM, Kim SH, Yoon HK, Sung KB, Kim PN. Medium-sized (3.1-5.0 cm) hepatocellular carcinoma: transarterial chemoembolization plus radiofrequency ablation versus radiofrequency ablation alone. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1624–1629. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1673-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ni JY, Liu SS, Xu LF, Sun HL, Chen YT. Meta-analysis of radiofrequency ablation in combination with transarterial chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3872–3882. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i24.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng ZW, Zhang YJ, Liang HH, Lin XJ, Guo RP, Chen MS. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma treated with sequential transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and RF ablation versus RF ablation alone: a prospective randomized trial. Radiology. 2012;262:689–700. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minagawa M, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Kokudo N. Selection criteria for repeat hepatectomy in patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2003;238:703–710. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094549.11754.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaibori M, Kubo S, Nagano H, Hayashi M, Haji S, Nakai T, Ishizaki M, Matsui K, Uenishi T, Takemura S, et al. Clinicopathological features of recurrence in patients after 10-year disease-free survival following curative hepatic resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2013;37:820–828. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-1902-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koike Y, Shiratori Y, Sato S, Obi S, Teratani T, Imamura M, Hamamura K, Imai Y, Yoshida H, Shiina S, et al. Risk factors for recurring hepatocellular carcinoma differ according to infected hepatitis virus-an analysis of 236 consecutive patients with a single lesion. Hepatology. 2000;32:1216–1223. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.20237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borie F, Bouvier AM, Herrero A, Faivre J, Launoy G, Delafosse P, Velten M, Buemi A, Peng J, Grosclaude P, et al. Treatment and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: a population based study in France. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:505–509. doi: 10.1002/jso.21159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mazzaferro V, Battiston C, Perrone S, Pulvirenti A, Regalia E, Romito R, Sarli D, Schiavo M, Garbagnati F, Marchianò A, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of small hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients awaiting liver transplantation: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 2004;240:900–909. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000143301.56154.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Livraghi T, Solbiati L, Meloni MF, Gazelle GS, Halpern EF, Goldberg SN. Treatment of focal liver tumors with percutaneous radio-frequency ablation: complications encountered in a multicenter study. Radiology. 2003;226:441–451. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2262012198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]