Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive, debilitating, and fatal lung disease of unknown aetiology with no current cure. The pathogenesis of IPF remains unclear but repeated alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) injuries and subsequent apoptosis are believed to be among the initiating/ongoing triggers. However, the precise mechanism of apoptotic induction is hitherto elusive. In this study, we investigated expression of a panel of pro-apoptotic and cell cycle regulatory proteins in 21 IPF and 19 control lung tissue samples. We reveal significant upregulation of the apoptosis-inducing ligand TRAIL and its cognate receptors DR4 and DR5 in AEC within active lesions of IPF lungs. This upregulation was accompanied by pro-apoptotic protein p53 overexpression. In contrast, myofibroblasts within the fibroblastic foci of IPF lungs exhibited high TRAIL, DR4 and DR5 expression but negligible p53 expression. Similarly, p53 expression was absent or negligible in IPF and control alveolar macrophages and lymphocytes. No significant differences in TRAIL expression were noted in these cell types between IPF and control lungs. However, DR4 and DR5 upregulation was detected in IPF alveolar macrophages and lymphocytes. The marker of cellular senescence p21WAF1 was upregulated within affected AEC in IPF lungs. Cell cycle regulatory proteins Cyclin D1 and SOCS3 were significantly enhanced in AEC within the remodelled fibrotic areas of IPF lungs but expression was negligible in myofibroblasts. Taken together these findings suggest that, within the remodelled fibrotic areas of IPF, AEC can display markers associated with proliferation, senescence, and apoptotosis, where TRAIL could drive the apoptotic response. Clear understanding of disease processes and identification of therapeutic targets will direct us to develop effective therapies for IPF.

Keywords: Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, TRAIL, DR4, DR5, immunohistochemistry, p53, p21WAF1

Introduction

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic progressive fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of unknown aetiology, occurring primarily in older adults and limited to the lungs [1]. Mean survival is 2-3 years from initial diagnosis and, to date there is no effective treatment able to halt or reverse disease progression [2]. Histological features of IPF, as defined by Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP), include a diagnostic patchwork of unaffected lung alternating with remodelled fibrotic lung involving type I alveolar epithelial cell (AEC) destruction, type II AEC hyperplasia and areas of inactive collagen type scaring. Formation of fibroblastic foci is a key feature of UIP reflecting sites of active ongoing fibrogenesis [1,3].

The pathogenesis of IPF is not fully understood; however, current evidence suggests a failure or imbalance in a number of signalling pathways eventually leading to alveolar epithelial cell loss and myofibroblast accumulation. Myofibroblasts are contractile differentiated fibroblast phenotypes responsible for the excessive collagen deposition and tissue remodelling seen in IPF [4]. Excessive myofibroblast accumulation is believed to be secondary to repeated AEC injuries [5,6]. Due to subtle evidence of local or systemic inflammatory responses during disease progression, it is possible that affected/injured AEC undergo apoptosis rather than necrosis. This concept of excessive AEC apoptosis is supported by a growing body of evidence [7-9]. More recently, it has been reported that severe and chronic endoplasmic reticulum stress in AEC could be an underlying cause of AEC apoptosis, potentially linked with sporadic IPF [10-12]. A significant up-regulation of pro-apoptotic proteins p53, bax and caspase-3 with associated down-regulation of anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 was found in IPF alveolar epithelial cells [13]. Fas-FasL-mediated apoptosis in alveolar epithelial cells and their association in aberrant alveolar wound repair in IPF have been implicated [14]. However, another potent apoptosis-inducing molecule TRAIL and its involvement in IPF pathogenesis remains widely unexplored.

TRAIL (TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand, also known as Apo2L), a member of the TNF superfamily, has been shown to induce apoptosis via DR4 and DR5 receptor binding [15-17]. TRAIL has been reported to induce apoptosis in various tumour cells but not in nontransformed, normal cells [18-20]. It has also been demonstrated that soluble human TRAIL can induce apoptosis in human primary lung airway epithelial cells and hepatocytes [21,22]. Moreover, TRAIL and its receptors have been implicated in several extra-pulmonary disease pathologies including chronic pancreatitis [23], diabetic nephropathy [24], inflammatory bowel diseases [25,26], chronic cholestatic disease [27], hepatitis [28] and intervertebral disk degeneration [29]. We have previously demonstrated that TRAIL-expressing club (Clara) cells could be involved in AEC apoptosis and subsequent fibrogenesis in IPF [21].

Here, we have explored expression of TRAIL and its apoptosis executing receptor pair DR4 and DR5 in lung tissue samples of 21 IPF cases and 19 controls using a semi-quantitative immunohistochemical analysis [30]. In normal lungs, alveolar progenitors, type II AEC, remain quiescent but proliferate and differentiate into type I AEC as part of a reparative process [31]. In IPF, type II AEC appeared hyperplastic within the affected fibrotic lung suggestive of attempted repair. Our data suggests widespread upregulation of TRAIL, DR4 and DR5 in type II AEC and myofibroblasts of IPF lungs; with specific pro-apoptotic marker p53 expression and TUNEL-positive signals only detected in type II AEC within diseased alveolar areas. TRAIL receptors DR4 and DR5 were expressed in macrophages and lymphocytes with no apparent differences in TRAIL expression between IPF and control samples. The p53 expression was either absent or negligible in IPF macrophages and lymphocytes. These findings suggest that TRAIL-mediated apoptosis could play a role in the relentless AEC destruction underlying the progressive pathogenesis of IPF.

Materials and methods

Study participants

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue samples from 21 IPF and 19 control subjects; histologically defined normal lung sections from subjects who had undergone lobectomy for cancer, were examined for expression of apoptotic and cell cycle markers. H&E stained slides from IPF tissue samples were reviewed by an independent pathologist to confirm a diagnosis of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) in line with recognised criteria [1]. The study received prior approval from the local research ethics committee (REC 08/H1203/6).

Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed following previously described methodology [30]. Briefly, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded lung tissue samples were deparaffinised in Xylene and rehydrated through a series of alcohols to water. Antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer (pH 6) microwaved for 20 minutes. Antibodies were optimised according to manufacturer’s instructions (Table 1). Immunohistochemistry was performed using the En Vision system (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). For dual immunohistochemistry staining, an avidin biotin block was performed after completion of the first antibody labelled with Diaminobenzidine (DAB) to prevent cross reaction with the En Vision kit. The second antibody was labelled with Very Intense Purple (VIP, Lab Vision, UK). Sections were counterstained using either haematoxylin Z (CellPath, UK) or Alcian Blue.

Table 1.

Details of the antibodies, dilutions, incubation times and cellular localisation of markers used in this study

| Antibody (clone no) | Source | Dilution/incubation time | Localisation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclin D1 (SP4) | Lab Vision Corporation (USA) | 1:10, RT 30 mins | Nuclear |

| SOCS3 (ab3693) | Abcam (UK) | 1:100, RT 30 mins with PB | Cytoplasmic |

| p53 (DO-7) | Dako Cytomation (Denmark) | 1:800, RT 30 mins | Nuclear/cytoplasmic |

| p21WAF1 (SX118) | Dako Cytomation (Denmark) | 1:50, RT 30 mins | Nuclear |

| TRAIL (ab2435) | Abcam (UK) | 1:75, 30 mins RT with PB | Membrane/Cytoplasmic |

| DR4 (ab8414) | Abcam (UK) | 1:200, 30 mins RT with PB | Membrane |

| DR5 (ab8416) | Abcam (UK) | 1:800, 30 mins RT with PB | Membrane |

| proSP-C (ab40879) | Abcam (UK) | 1:1500, 30 min RT with PB | Cytoplasmic |

RT = room temperature, PB = protein block.

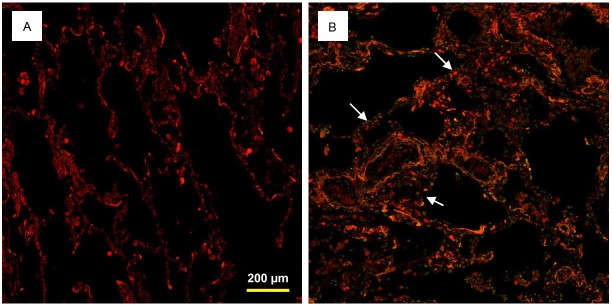

TUNEL assay

Combined TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end-labelling) and immunohistochemistry with proSP-C antibody on lung tissue was performed using In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, Fluorescein (Roche Applied Science, USA) following previously described methodology [21]. Briefly, samples were treated with proSP-C primary antibody (polyclonal, ab40879, dilution 1:250; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and visualised by secondary antibody anti-rabbit IgG-NL493 (dilution 1:200, NorthernLights, R & D System, MN, USA). Afterwards, TUNEL was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were examined under laser scanning confocal microscope and images were captured.

Semiquantitative analysis

Semiquantitative analysis was performed following previously described methodology [30]. Briefly, tissue sections were reviewed by the lead investigator alongside an independent pathologist and scored by examining expression of markers at sites of fibroblastic foci, type II AEC, alveolar macrophages and lymphocytes in IPF and control samples. For type II AEC in IPF samples, 100 hyperplasic cells were counted and the number of cells expressing each marker was recorded. The same was performed on normal appearing type II AEC in the control samples. This semi-quantitative analysis was also applied for lymphocytes and macrophages. A semi-quantitative analysis was used to compare groups using a modified Allred scoring system, also referred to as the Quick score method [32] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Modified Allred scoring system for semi-quantitative immunohistochemical analysis [32]

| Staining score | Positive staining cells (%) | Descriptive expression |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | No expression |

| 1 | <1 | Negligible expression |

| 2 | 1 to 10 | Scanty expression |

| 3 | 10 to 33 | Low-moderate expression |

| 4 | 33 to 66 | Moderate expression |

| 5 | >66 | Extensive expression |

Statistical analysis

The significance of difference between groups was determined by one way ANOVA, with post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis. A p-value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean). Statistical analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

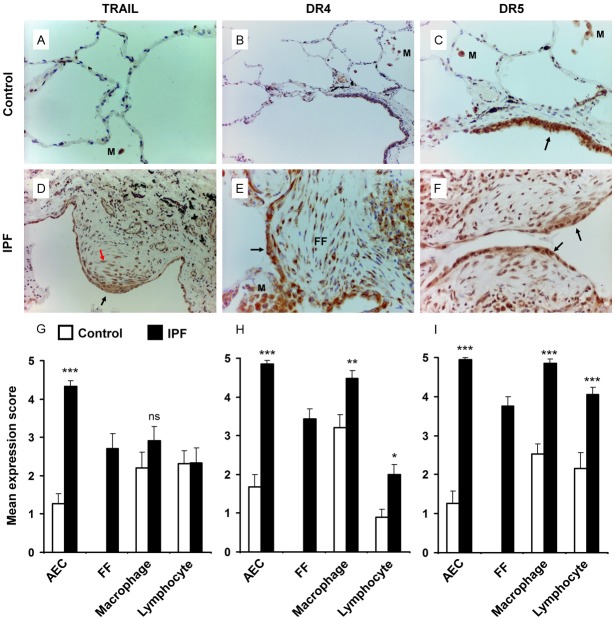

Widespread TRAIL and associated receptor upregulation in IPF lung tissue

The apoptotic ligand, TRAIL and corresponding receptors DR4 and DR5 have been implicated in extra-pulmonary disease pathogenesis [23-28]. Previously, we have demonstrated a putative pathognomic function of TRAIL-expressing club (Clara) cells in IPF [21]. Here we further explored the expression profile of TRAIL and its receptors in lung tissues obtained from 21 IPF cases and 19 healthy controls. TRAIL expression was significantly upregulated in AEC within the vicinity of the fibrotic lesions of IPF lungs compared to the alveolar regions of healthy controls (mean expression score 4.33 ± 0.14 vs 1.26 ± 0.26, p<0.0001) (Figure 1A, 1D, 1G). The myofibroblasts within the fibroblastic foci (FF) demonstrated a moderately high degree of TRAIL expression (mean expression score 2.71 ± 0.38) (Figure 1D, 1G). However, no significant differences in TRAIL expression were observed in macrophages and lymphocytes of IPF lungs when compared with those of healthy controls (Figure 1G). TRAIL receptors DR4 and DR5 were significantly upregulated in AEC (mean expression score DR4, 4.86 ± 0.08 IPF vs 1.86 ± 0.32 Control, p<0.0001; DR5, 4.95 ± 0.05 IPF vs 1.26 ± 0.32 Control, p<0.0001), macrophages (DR4, 4.48 ± 0.21 IPF vs 3.21 ± 0.33 Control, p<0.001; DR5, 4.86 ± 0.10 IPF vs 2.53 ± 0.26 Control, p<0.0001) and lymphocytes (DR4, 2.00 ± 0.26 IPF vs 0.89 ± 0.26 Control, p<0.05; DR5, 4.05 ± 0.19 IPF vs 2.16 ± 0.40 Control, p<0.0001) of IPF lungs vs. control counterparts (Figure 1B, 1C, 1E, 1F, 1H, 1I). Extensive DR4 and DR5 expression were detected in myofibroblasts of IPF lung tissue samples (mean expression score 3.43 ± 0.27 and 3.76 ± 0.23 respectively, Figure 1E, 1F, 1H, 1I). Overall, these data reflect a global upregulation of DR4 and DR5 in epithelial, mesenchymal and inflammatory cell populations of IPF lung; where, TRAIL upregulation was largely restricted to alveolar epithelial cells and myofibroblasts.

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis of IPF and control lungs for expression of TRAIL and its receptors DR4 and DR5. (A, D) TRAIL expression detection in the alveolar regions of normal (A) and IPF lung tissue (D). Negligible TRAIL expression was detected in control lung but was highly expressed in AEC (black arrow) and myofibroblasts (red arrow) of IPF lung. (B, E) Immunostaing for DR4 on normal (B) and IPF (E) lung tissue. High level of DR4 expression was detected in AEC over the fibrotic foci (FF), myofibroblasts and macrophages (M) of IPF lung (E), arrow indicates DR4 positive AEC. (C, F) Immunostaing for DR5 on normal (C) and IPF (F) lung tissue. Bronchiolar epithelial cells stains positive for DR5 (arrow) but AEC are negative in control lung. DR5 positively stained macrophages (M) are observed in control lung. Significantly increased DR5 expression is detected in AEC (arrows), myofibroblasts, macrophages and lymphocytes (F). (G-I) Mean expression score profiles for TRAIL (G), DR4 (H) and DR5 (I) on control (open bar) and IPF (black bar) lungs respectively. FF indicates myofibroblasts within the fibroblastic foci. Image magnification 400x (A-C) and 200x (D-F). *p<0.05, **p<0.001, ***p<0.0001 vs control. ns = not significant, M = macrophages.

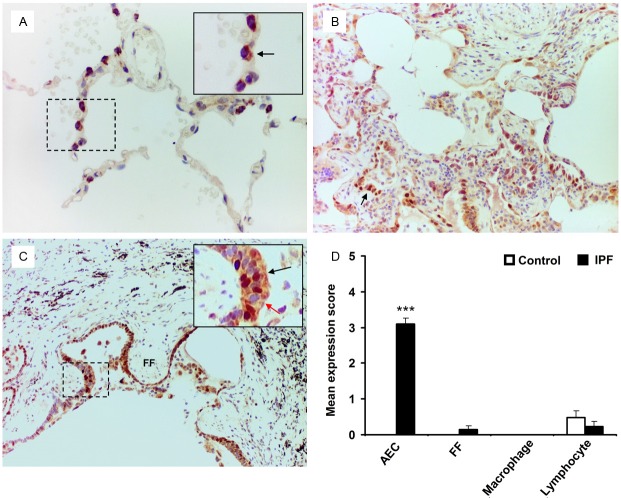

Pro-apoptotic marker p53 expression profile in IPF lungs

To evaluate p53 expression in type II AEC, we performed dual immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis using anti-proSP-C and anti-p53 antibodies on IPF and control lung tissue samples. A significant level of nuclear p53 expression was detected in type II AEC within the fibrotic areas of IPF lungs; in contrast its expression was undetectable in control lung tissue samples (mean expression score 3.10 ± 0.17 vs 0.00, p<0.0001) (Figure 2). Only two out of 21 IPF cases demonstrated myofibroblast p53 expression with expression scores of 2.00 and 1.00; the overall mean expression score was 0.14 ± 0.10 (Figure 2C, 2D). No p53 expression was detected in macrophages of IPF or control lung tissue samples (Figure 2D). There was ngligible expression of p53 in lymphocytes of both IPF and control lung tissues with no statistical significant difference (Figure 2D). In addition, the TUNEL assay detected an increased number of Tunel positive AEC within the affected fibrotic lesions of IPF lung tissue samples (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Dual-labelled immunohistochemistry of IPF and control lung samples for p53 and SP-C expression. (A) SP-C cytoplasmic stained (brown) AEC are negative for p53 nuclear staining (arrow, negative blue nucleus). (B) Patchy nuclear expression of p53 (very intense purple) is observed in SP-C positive AEC within the fibrotic lesions of IPF lung samples (arrow). (C) Increased level of dual-positive p53/SP-C AEC are detected at the areas covering fibroblastic foci (FF) (inset, black arrow indicates dual positive cells, red arrow indicates p53 negative but SP-C positive AEC). Myofibroblasts within the fibroblastic foci (FF) are negative for both p53 and SP-C. (D) Mean expression score profiles for p53 on control (open bar) and IPF (black bar) lung tissue samples respectively. FF indicates myofibroblasts within the fibroblastic foci. Image magnification 400x (A), 200x (B, C). ***p<0.0001 vs control.

Figure 3.

Dual TUNEL and immunohistochemistry with proSP-C on human lung tissue samples. TUNEL positive AEC were not detected in control lung tissues (A). Increased number of TUNEL positive (green nuclei, arrows) AEC (red cytoplasmic stain) were detected in IPF lung tissue sample (B).

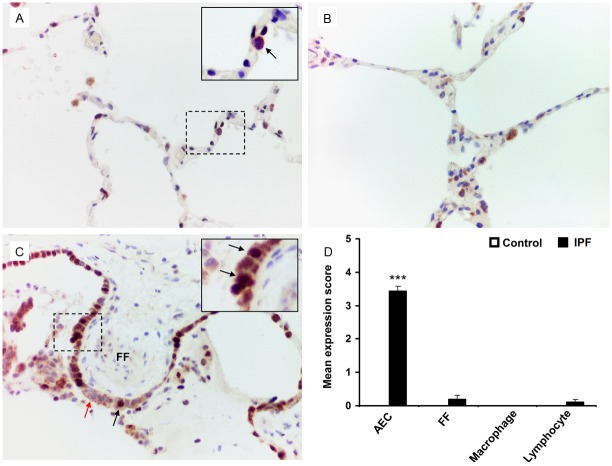

p21WAF1 upregulation in AEC of IPF lungs

p21WAF1, a cell cycle arrest molecule, expression in type II AEC was evaluated by conducting dual immunohistochemical analysis with anti-proSP-C and anti-p21WAF1 antibodies. No p21WAF1 expression was detected in the AEC of control lung tissue samples (Figure 4A). Conserved areas of IPF lung did not express p21WAF1 within alveoli (Figure 4B). Nuclear expression of p21WAF1 in AEC within the fibrotic areas of the IPF lungs was variable but significantly increased compared to control lungs (mean expression score 3.43 ± 0.15; p<0.0001) (Figure 4C, 4D). Myofibroblasts within the fibroblastic foci demonstrated negligible expression of p21WAF1 (mean expression score 0.19 ± 0.13) (Figure 4C, 4D). p21WAF1 expression was also negligible or absent in lymphocytes and macrophages in both IPF and control lung tissue samples (Figure 4D). The pattern of p21WAF expression appears similar to that of p53 in control and IPF lung tissues.

Figure 4.

Dual-labelled immunohistochemistry of IPF and control lung samples for p21WAF1 and SP-C expression. A. SP-C cytoplasmic stained (brown) AEC show negative staining for p21WAF1 nuclear staining (arrow) in control lung. B. A representative image of conserved area of IPF lung demonstrating no p21WAF1 expression. C. Increased level of dual-positive p21WAF1/SP-C AEC (VIP stain showing dark brown against brown cytoplasmic background) are detected at the areas covering fibroblastic foci (FF) (black arrows). p21WAF1 negative but SP-C positive type II AEC are shown by red arrow. D. Mean expression score profiles for p21WAF1 on control (open bar) and IPF (black bar) lung tissue samples respectively. FF indicates myofibroblasts within the fibroblastic foci. Image magnification 400x for all. ***p<0.0001 vs control.

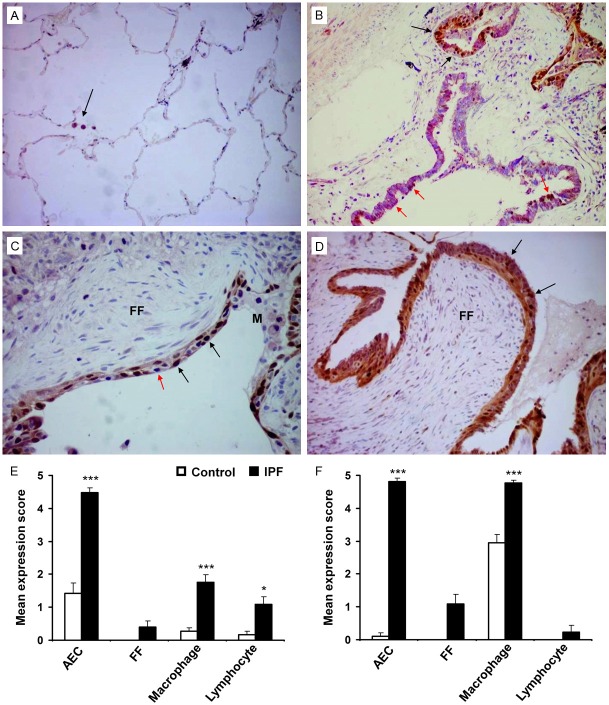

Cyclin D1 and SOCS3 expression

Cyclin D1 and SOCS3 expression in IPF lung tissue samples was assessed using dual immunohistochemical analysis. These markers were selected for dual IHC as SOCS3 has been shown to inactivate STAT3 resulting in the promotion of Cyclin D1 leading to cell cycle progression [33]. Nuclear Cyclin D1 expression was scanty in control AEC compared to extensive expression in hyperplastic AEC in the IPF group (mean expression score 1.42 ± 0.32 vs 4.48 ± 0.15, p<0.0001) (Figure 5A-E). Low but significant Cyclin D1 expression was detected in macrophages (0.26 ± 0.10 vs 1.75 ± 0.25, p<0.0001) and lymphocytes (0.16 ± 0.12 vs 1.10 ± 0.22, p<0.05) within the fibrotic IPF lung tissues compared to control lung samples (Figure 5E). Cyclin D1 expression was negligible within the fibroblastic foci (mean expression score 0.4 ± 0.18). A significant increase in cytoplasmic SOCS3 expression was observed in IPF AEC compared with control cells (mean expression score 4.81 ± 0.11 vs 0.11 ± 0.11, p<0.0001) (Figure 5B, 5D, 5F). High levels of SOCS3 expression were also observed in IPF macrophages compared to control (mean expression score 4.76 ± 0.10 vs 2.95 ± 0.26, p<0.0001) (Figure 5F). However, SOCS3 expression in IPF lymphocytes was negligible and absent in control lung lymphocytes (Figure 5F). Scanty expression of SOCS3 was identified within the fibroblastic foci (mean expression score 1.10 ± 0.29) (Figure 5C, 5D, 5F). In most of the cases, cells were co-expressing Cyclin D1 with SOCS3.

Figure 5.

Dual-labelled immunohistochemistry of IPF and control lung samples for Cyclin D1 and SOCS3 expression. (A) Representative histological image of control lung tissue shows no Cyclin D1 or SOCS expression within the alveoli. SOCS3 expression is expressed by macrophages (purple cytoplasmic stain) (arrow). (B) IPF lung tissue demonstrates dual expression of nuclear Cyclin D1 (brown) and cytoplasmic SOCS3 (purple) in the hyperplastic AEC (black arrows). Extensive expression of SOCS3 within the ciliated epithelium was also noted (red arrows). (C, D) Two separate IPF tissue samples with AEC overlying fibroblastic foci expressing both Cyclin D1 (brown) and SOCS3 (purple), however, cells within the foci did not express either marker. Red arrow indicates dual-negative AEC (C). (E, F) Mean expression score profiles for Cyclin D1 and SOCS3 on 19 control (open bar) and 21 IPF (black bar) lung tissue samples respectively. FF indicates myofibroblasts within the fibroblastic foci. Image magnification 200x (A), 400x (B-D). *p<0.05, ***p<0.0001 vs control. M = macrophages.

Discussion

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is considered to be a consequence of aberrant alveolar wound repair driven by complex interactive events of AEC apoptosis, dysregulated epithelial-mesenchymal homeostasis, basement membrane disruption and unbalanced immune response [5-9,34,35]. One key feature, overt AEC apoptosis in IPF, is evident but the initiating trigger remains elusive. In this study we have demonstrated a widespread upregulation of TRAIL and its pro-apoptotic receptors DR4 and DR5 in hyperplastic AEC of IPF lung tissue samples. Although TRAIL and its receptors are detected in most tissue and organ systems in humans [36], their precise physiological role is widely unknown. The main function of TRAIL appears to be as a negative regulator of the immune system to prevent autoimmunity [37]. TRAIL may also serve as a critical effector molecule on activated T and B lymphocytes, natural killer cells, monocytes, and dendritic cells [38-40].

Initially, it was reported that TRAIL only induces apoptosis in transformed cancer cells; however, increasing evidence suggests that TRAIL can also trigger apoptosis in non-transformed primary human hepatocytes, thymocytes, neural cells and small airway epithelial cells (SAEC) [21,22,37,41]. Moreover, TRAIL-mediated apoptosis has been reported in many chronic disease states. For example, in chronic pancreatitis the pancreatic stellate cells overexpress TRAIL and directly contribute to the acinar regression through induction of apoptosis in parenchymal cells via a TRAIL-receptor-mediated apoptosis mechanism [23]. TRAIL-mediated apoptosis has been reported as a key mediator for progression of human diabetic nephropathy where TRAIL-overexpression in renal tubular epithelial cells is associated with severe tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis [24]. Other studies have demonstrated upregulation of TRAIL in intestinal epithelial cells associated with epithelial cell destruction through TRAIL-mediated apoptosis and progression of inflammatory bowel disease such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, while down-regulation is associated with the refractory stages of the disease [25,26]. TRAIL involvement has also been demonstrated in the pathogenesis of bronchial asthma. Administration of recombinant TRAIL induces asthma-like pathological features in animal models. High levels of TRAIL have also been detected in the sputum of asthmatic patients [42]. We previously reported that direct contact of TRAIL-expressing club (Clara) cells can induce apoptosis in AEC, and that TRAIL-expressing club cells are present within the apoptotic AEC population of the fibrotic areas in IPF lungs [21]. In this current study, utilising the same cohort of lung tissue samples we report an upregulation of TRAIL and its cognate receptors in AEC within the fibrotic lesions of IPF lungs. We therefore suggest a possible pathognomic role of TRAIL in the initiation and/or progression of IPF; albeit that a recent non-quantitative immunohistochemistry study on only 5 IPF cases showed a relatively low TRAIL expression in IPF alveolar epithelial cells [43].

In support of our hypothesis that TRAIL-mediated AEC apoptosis is a key event in IPF pathogenesis, we have demonstrated preferential expression of the pro-apoptotic protein, p53, in AEC within the affected fibrosed areas of IPF lungs, in line with previous findings [13,44]. The presence of apoptotic AEC in IPF lung tissue was further confirmed by the TUNEL assay. Wild-type p53 acts to suppress cell growth through its downstream cell cycle arrest molecule p21WAF1 whilst the cell attempts to repair DNA damage; however, if DNA damage is irreparable it promotes apoptosis [45,46]. The p21 expression is simultaneously induced with p53 after cellular stress, and is a crucial downstream effector in the p53 specific pathway of cell cycle control in mammalian cells [47]. Data shows that p21 modulates cell survival either by promoting DNA repair or by ensuing cell death caused by various stress stimuli [48-50]. Over activity of p53, however, can bypass p21-mediated cell cycle arrest and execute cell apoptosis. The p53 activity is negatively regulated by interaction with Mdm2 protein that normally targets p53 for degradation via the ubiquitin-mediated proteasome pathway [51]. Interestingly, p53 conjugation with Mdm2 was found to be decreased in IPF lung tissue samples compared with controls, suggesting an exaggerated p53 activity [44]. In fact, DNA damage and apoptosis have been associated with the upregulation of p53 and p21 proteins in bronchiolar and alveolar epithelial cells in IPF lungs [52]. Our data adds to the above findings, and suggests that a TRAIL-p53 apoptotic axis could be activated during fibrogenesis of IPF. Moreover, AEC within the fibrotic milieu are likely to be more susceptible to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis due to local elevation of TNF-α and IL-1β [53-55]. It has been reported that inflammatory cytokines, TNF-α and IL-1β, can sensitise normal primary human epithelial cells to TRAIL-mediated apoptosis [56,57]. Furthermore, studies have identified TRAIL as a p53-target gene that may play a central role in mediating p53-dependent cell death. TRAIL receptors DR4, DR5 are directly regulated by p53 and so the induction of TRAIL in a p53 -dependent manner suggests that p53 not only controls pro-apoptotic receptor expression but also expression of the TRAIL ligand [58-60]. These previous studies suggest that in our study AEC populations with concurrent upregulation of p53 and TRAIL machineries, are likely to be vulnerable to apoptosis. However, due to the observed simultaneous upregulation of p21WAF1 in IPF AEC, we cannot preclude that a subpopulation of AEC undergo cell cycle arrest or senescence.

Although AEC in IPF lungs are prone to apoptosis, it has been reported that myofibroblasts and inflammatory cells of IPF lungs are relatively resistant to apoptosis [61,62]. Our data shows a negligible expression of p53 and p21WAF1 in the myofibroblast populations within the fibroblastic foci, suggesting an apoptotic-resistant phenotype. Furthermore, due to negligible p53 expression, we can speculate that myofibroblasts are not under genotoxic stress which is likely to be occurring in AEC of IPF lungs. However, we cannot explain why, in spite of upregulation of TRAIL and its receptors in myofibroblasts, these cells would appear to be resistant to apoptosis. Studies show that upregulation of apoptosis-resistant proteins survivin and XIAP in IPF myofibroblasts prevent them from undergoing Fas-mediated apoptosis [63,64]. Therefore, further exploration is required to determine whether these anti-apoptotic mediators have any negative role on TRAIL-mediated apoptosis, particularly in IPF myofibroblasts. The recent small non-quantitative study on 3 controls and 5 IPF cases by McGrath and colleague [43] demonstrated a reduction of TRAIL expression in IPF alveolar macrophages which contradicts our semi-quantitative data demonstrating no significant changes in TRAIL expression in alveolar macrophages and lymphocytes between IPF and control lung tissue samples. Moreover, due to absent or negligible expression of p53 and p21WAF1 in IPF and normal macrophages and lymphocytes, it could be suggested that these inflammatory cell pools are apoptotic-resistant. However, DR4 and DR5 expression was high in both of these cell types in IPF lungs compared to controls.

In IPF pathogenesis type I AEC destruction is observed, with type II AEC proliferation occurring in an attempt at alveolar wall repair. Our study, exhibits an upregulation of Cyclin D1 and SOCS3 in AEC of affected areas of IPF lungs suggesting a proliferative phenotype of type II AEC. Cyclin D1, a cell cycle regulator protein, complexes with cyclin-dependent kinase-4 (cdk4) and propagates cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase [65]. Suppressor of cytokine signaling SOCS3 inhibits STAT3 resulting in the promotion of Cyclin D1, which then binds with cdk4 driving the cell through the S-phase of the cell cycle [33]. Evidence of a proliferative population of type II AEC was reported in our previous work demonstrated by an elevated level of the cell proliferation marker Ki-67 protein [30]. In contrast, myofibroblasts, in this present study, display negligible expression of both Cyclin D1 and SOCS3, and negligible Ki-67 expression in our previous study on the same lung samples [30]. Considering our findings and existing literature, we suggest that in IPF, AEC exposed to genotoxic stress might undergo apoptosis through a TRAIL-mediated pathway driving a pathognomic process that promotes an overt fibroproliferative response and remodelling of the lung. Better understanding of these complex pathophysiological dynamics should be further explored on relevant in vitro and animal models, although this is hampered by current lack of replicable models of IPF. Using sophisticated exploratory technologies it may be possible in future to dissect these intertwined patho-mechanisms in actual IPF affected lungs and identify key driving targets for development of selective and effective anti-IPF therapies.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Daniel Gey van Pittius, consultant histopathologist at the University Hospital of North Staffordshire for his assistance with histological analysis. N Lomas was supported by a grant from the Institute of Biomedical Science and a Keele University Acorn Studentship.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier JF, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, Lynch DA, Ryu JH, Swigris JJ, Wells AU, Ancochea J, Bouros D, Carvalho C, Costabel U, Ebina M, Hansell DM, Johkoh T, Kim DS, King TE Jr, Kondoh Y, Myers J, Müller NL, Nicholson AG, Richeldi L, Selman M, Dudden RF, Griss BS, Protzko SL, Schünemann HJ ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2009-040GL. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gribben J, Hubbard RB, Le-Jeune I, Smith CJ, West J, Tata LJ. Incidence and mortality of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis in the UK. Thorax. 2006;61:980–985. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.062836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dacic S, Yousem SA. Histologic classification of idiopathic chronic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29:S5–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maher TM, Wells AU, Laurent GJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: multiple causes and mechanisms? Eur Respir J. 2007;30:835–839. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00069307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A. American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society & American College of Chest Physicians. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:136–151. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-2-200101160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selman M, Pardo A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an epithelial/fibroblastic cross-talk disorder. Respir Res. 2002;3:3. doi: 10.1186/rr175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uhal BD, Joshi I, Hughes WF, Ramos C, Pardo A, Selman M. Alveolar epithelial cell death adjacent to underlying myofibroblasts in advanced fibrotic human lung. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L1192–1199. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.6.L1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuwano K, Miyazaki H, Hagimoto N, Kawasaki M, Fujita M, Kunitake R, Kaneko Y, Hara N. The involvement of Fas-Fas ligand pathway in fibrosing lung diseases. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:53–60. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.1.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbas-Filho JV, Ferreira MA, Sesso A, Kairalla RA, Carvalho CR, Capelozzi VL. Evidence of type II pneumocyte apoptosis in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IFP)/usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:132–138. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.2.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Korfei M, Ruppert C, Mahavadi P, Henneke I, Markart P, Koch M, Lang G, Fink L, Bohle RM, Seeger W, Weaver TE, Guenther A. Epithelial endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in sporadic idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:838–846. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-313OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lawson WE, Cheng DS, Degryse AL, Tanjore H, Polosukhin VV, Xu XC, Newcomb DC, Jones BR, Roldan J, Lane KB, Morrisey EE, Beers MF, Yull FE, Blackwell TS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress enhances fibrotic remodeling in the lungs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:10562–10567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107559108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tanjore H, Blackwell TS, Lawson WE. Emerging evidence for endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L721–9. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00410.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plataki M, Koutsopoulos AV, Darivianaki K, Delides G, Siafakas NM, Bouros D. Expression of apoptotic and antiapoptotic markers in epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2005;127:266–274. doi: 10.1378/chest.127.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuwano K, Miyazaki H, Hagimoto N, Kawasaki M, Fujita M, Kunitake R, Kaneko Y, Hara N. The involvement of Fas-Fas ligand pathway in fibrosing lung diseases. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:53–60. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.1.2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan G, O’Rourke K, Chinnaiyan AM, Gentz R, Ebner R, Ni J, Dixit VM. The receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. Science. 1997;276:111–113. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walczak H, Degli-Esposti MA, Johnson RS, Smolak PJ, Waugh JY, Boiani N, Timour MS, Gerhart MJ, Schooley KA, Smith CA, Goodwin RG, Rauch CT. TRAIL-R2: a novel apoptosis-mediating receptor for TRAIL. EMBO J. 1997;16:5386–5397. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheridan JP, Marsters SA, Pitti RM, Gurney A, Skubatch M, Baldwin D, Ramakrishnan L, Gray CL, Baker K, Wood WI, Goddard AD, Godowski P, Ashkenazi A. Control of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy receptors. Science. 1997;277:818–821. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitti RM, Marsters SA, Ruppert S, Donahue CJ, Moore A, Ashkenazi A. Induction of apoptosis by Apo-2 ligand, a new member of the tumor necrosis factor cytokine family. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12687–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.22.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiley SR, Schooley K, Smolak PJ, Din WS, Huang CP, Nicholl JK, Sutherland GR, Smith TD, Rauch C, Smith CA, et al. Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity. 1995;3:673–82. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walczak H, Miller RE, Ariail K, Gliniak B, Griffith TS, Kubin M, Chin W, Jones J, Woodward A, Le T, Smith C, Smolak P, Goodwin RG, Rauch CT, Schuh JC, Lynch DH. Tumoricidal activity of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:157–63. doi: 10.1038/5517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akram KM, Lomas NJ, Spiteri MA, Forsyth NR. Club cells inhibit alveolar epithelial wound repair via TRAIL-dependent apoptosis. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:683–94. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00213411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jo M, Kim TH, Seol DW, Esplen JE, Dorko K, Billiar TR, Strom SC. Apoptosis induced in normal human hepatocytes by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Nat Med. 2000;6:564–7. doi: 10.1038/75045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasel C, Dürr S, Rau B, Sträter J, Schmid RM, Walczak H, Bachem MG, Möller P. In chronic pancreatitis, widespread emergence of TRAIL receptors in epithelia coincides with neoexpression of TRAIL by pancreatic stellate cells of early fibrotic areas. Lab Invest. 2003;83:825–36. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000073126.56932.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorz C, Benito-Martín A, Boucherot A, Ucero AC, Rastaldi MP, Henger A, Armelloni S, Santamaría B, Berthier CC, Kretzler M, Egido J, Ortiz A. The death ligand TRAIL in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:904–14. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007050581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Begue B, Wajant H, Bambou JC, Dubuquoy L, Siegmund D, Beaulieu JF, Canioni D, Berrebi D, Brousse N, Desreumaux P, Schmitz J, Lentze MJ, Goulet O, Cerf-Bensussan N, Ruemmele FM. Implication of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in inflammatory intestinal epithelial lesions. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1962–1974. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brost S, Koschny R, Sykora J, Stremmel W, Lasitschka F, Walczak H, Ganten TM. Differential expression of the TRAIL/TRAIL receptor system in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Pathol Res Pract. 2010;206:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takeda K, Kojima Y, Ikejima K, Harada K, Yamashina S, Okumura K, Aoyama T, Frese S, Ikeda H, Haynes NM, Cretney E, Yagita H, Sueyoshi N, Sato N, Nakanuma Y, Smyth MJ, Okumura K. Death receptor 5 mediated-apoptosis contributes to cholestatic liver disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:10895–900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802702105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng SJ, Wang P, Tsabary G, Chen YH. Critical roles of TRAIL in hepatic cell death and hepatic inflammation. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:58–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI200419255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertram H, Nerlich A, Omlor G, Geiger F, Zimmermann G, Fellenberg J. Expression of TRAIL and the death receptors DR4 and DR5 correlates with progression of degeneration in human intervertebral disks. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:895–905. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lomas NJ, Watts KL, Akram KM, Forsyth NR, Spiteri MA. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: immunohistochemical analysis provides fresh insights into lung tissue remodelling with implications for novel prognostic markers. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:58–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fehrenbach H. Alveolar epithelial type II cell: defender of the alveolus revisited. Respir Res. 2001;2:33–46. doi: 10.1186/rr36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harvey JM, Clark GM, Osborne CK, Allred DC. Estrogen receptor status by immunohistochemistry is superior to the ligand-binding assay for predicting response to adjuvant endocrine therapy in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999;17:1474–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.5.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lu Y, Fukuyama S, Yoshida R, Kobayashi T, Saeki K, Shiraishi H, Yoshimura A, Takaesu G. Loss of SOCS3 gene expression converts STAT3 function from anti apoptotic to pro-apoptotic. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36683–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Corrin B, Dewar A, Rodriguez-Roisin R, Turner-Warwick M. Fine structural changes in cryptogenic alveolitis and asbestosis. J Pathol. 1985;147:107–119. doi: 10.1002/path.1711470206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tzouvelekis A, Bouros E, Bouros D. The immunology of pulmonary fibrosis: the role of Th1/Th2/Th17/Treg cells. Pneumon. 2010;23:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daniels RA, Turley H, Kimberley FC, Liu XS, Mongkolsapaya J, Ch’En P, Xu XN, Jin BQ, Pezzella F, Screaton GR. Expression of TRAIL and TRAIL receptors in normal and malignant tissues. Cell Res. 2005;15:430–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamhamedi-Cherradi SE, Zheng SJ, Maguschak KA, Peschon J, Chen YH. Defective thymocyte apoptosis and accelerated autoimmune diseases in TRAIL(-/-) mice. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:255–60. doi: 10.1038/ni894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mariani SM, Krammer PH. Surface expression of TRAIL/Apo-2 ligand in activated mouse T and B cells. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:1492–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199805)28:05<1492::AID-IMMU1492>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zamai L, Ahmad M, Bennett IM, Azzoni L, Alnemri ES, Perussia B. Natural killer (NK) cell-mediated cytotoxicity: differential use of TRAIL and Fas ligand by immature and mature primary human NK cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2375–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fanger NA, Maliszewski CR, Schooley K, Griffith TS. Human dendritic cells mediate cellular apoptosis via tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) J Exp Med. 1999;190:1155–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.8.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martin-Villalba A, Herr I, Jeremias I, Hahne M, Brandt R, Vogel J, Schenkel J, Herdegen T, Debatin KM. CD95 ligand (Fas-L/APO-1L) and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand mediate ischemia-induced apoptosis in neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3809–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03809.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weckmann M, Collison A, Simpson JL, Kopp MV, Wark PA, Smyth MJ, Yagita H, Matthaei KI, Hansbro N, Whitehead B, Gibson PG, Foster PS, Mattes J. Critical link between TRAIL and CCL20 for the activation of TH2 cells and the expression of allergic airway disease. Nat Med. 2007;13:1308–15. doi: 10.1038/nm1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McGrath EE, Lawrie A, Marriott HM, Mercer P, Cross SS, Arnold N, Singleton V, Thompson AA, Walmsley SR, Renshaw SA, Sabroe I, Chambers RC, Dockrell DH, Whyte MK. Deficiency of tumour necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand exacerbates lung injury and fibrosis. Thorax. 2012;67:796–803. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nakashima N, Kuwano K, Maeyama T, Hagimoto N, Yoshimi M, Hamada N, Yamada M, Nakanishi Y. The p53-Mdm2 association in epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and non-specific interstitial pneumonia. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:583–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.022632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ko LJ, Prives C. p53: puzzle and paradigm. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1054–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.9.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kastan MB, Onyekwere O, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Craig RW. Participation of p53 protein in the cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6304–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.El-Deiry WS, Harper JW, O’Connor PM, Velculescu VE, Canman CE, Jackman J, Pietenpol JA, Burrell M, Hill DE, Wang Y, Wiman KG, Mercer E, Kastan MB, Kohn KW, Elledge SJ, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. WAF1/CIP1 is induced in p53 mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1169–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O’Reilly MA, Staversky RJ, Watkins RH, Reed CK, de Mesy Jensen KL, Finkelstein JN, Keng PC. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 protects the lung from oxidative stress. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:703–10. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.6.4355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bissonnette N, Hunting DJ. p21-induced cycle arrest in G1 protects cells from apoptosis induced by UV-irradiation or RNA polymerase II blockage. Oncogene. 1998;16:3461–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu Y, Yamagishi N, Yagi T, Takebe H. Mutated p21(WAF1/CIP1/SDI1) lacking CDK-inhibitory activity fails to prevent apoptosis in human colorectal carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1998;16:705–712. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Slee EA, O’Connor DJ, Lu X. To die or not to die: how does p53 decide? Oncogene. 2004;23:2809–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuwano K, Kunitake R, Kawasaki M, Nomoto Y, Hagimoto N, Nakanishi Y, Hara N. p21Waf1/Cip1/Sdi1 and p53 expression in association with DNA strand breaks in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;15:477–83. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nash JR, McLaughlin PJ, Butcher D, Corrin B. Expression of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis. Histopathology. 1993;22:343–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ziegenhagen MW, Schrum S, Zissel G, Zipfel PF, Schlaak M, Müller-Quernheim J. Increased expression of proinflammatory chemokines in bronchoalveolar lavage cells of patients with progressing idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis. J Investig Med. 1998;46:223–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson MS, Madala SK, Ramalingam TR, Gochuico BR, Rosas IO, Cheever AW, Wynn TA. Bleomycin and IL-1beta-mediated pulmonary fibrosis is IL-17A dependent. J Exp Med. 2010;207:535–52. doi: 10.1084/jem.20092121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bretz JD, Mezosi E, Giordano TJ, Gauger PG, Thompson NW, Baker JR Jr. Inflammatory cytokine regulation of TRAIL-mediated apoptosis in thyroid epithelial cells. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:274–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mezosi E, Wang SH, Utsugi S, Bajnok L, Bretz JD, Gauger PG, Thompson NW, Baker JR Jr. Interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha sensitize human thyroid epithelial cells to TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-induced apoptosis through increases in procaspase-7 and bid, and the down-regulation of p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:250–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuribayashi K, Krigsfeld G, Wang W, Xu J, Mayes PA, Dicker DT, Wu GS, El-Deiry WS. TNFSF10 (TRAIL), a p53 target gene that mediates p53-dependent cell death. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:2034–8. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.12.7460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu X, Yue P, Khuri FR, Sun SY. p53 upregulates death receptor 4 expression through an intronic p53 binding site. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5078–83. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meng RD, El-Deiry WS. p53-independent upregulation of KILLER/DR5 TRAIL receptor expression by glucocorticoids and interferon-gamma. Exp Cell Res. 2001;262:154–69. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Drakopanagiotakis F, Xifteri A, Polychronopoulos V, Bouros D. Apoptosis in lung injury and fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:1631–8. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00176807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Drakopanagiotakis F, Xifteri A, Tsiambas E, Karameris A, Tsakanika K, Karagiannidis N, Mermigkis D, Polychronopoulos V, Bouros D. Decreased apoptotic rate of alveolar macrophages of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Med. 2012;2012:981730. doi: 10.1155/2012/981730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sisson TH, Maher TM, Ajayi IO, King JE, Higgins PD, Booth AJ, Sagana RL, Huang SK, White ES, Moore BB, Horowitz JC. Increased survivin expression contributes to apoptosis-resistance in IPF fibroblasts. Adv Biosci Biotechnol. 2012;3:657–664. doi: 10.4236/abb.2012.326085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ajayi IO, Sisson TH, Higgins PD, Booth AJ, Sagana RL, Huang SK, White ES, King JE, Moore BB, Horowitz JC. X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis regulates lung fibroblast resistance to Fas-mediated apoptosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;49:86–95. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0224OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baldin V, Lukas J, Marcote MJ, Pagano M, Draetta G. Cyclin D1 is a nuclear protein required for cell cycle progression in G1. Genes Dev. 1993;7:812–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]