Abstract

Endometriosis, diagnosed with ectopically implanted endometrial stromal cells (ESC) and epithelial cells to a location outside the uterine cavity, seriously threaten the quality of life and reproductive ability of women, yet the mechanisms and the pathophysiology of the disease remain unclear. Specially, the functional changes of ESC during endometriosis progression need in-depth investigation. In this study, we characterized mechanical properties of normal ESC (NESC) from healthy women and eutopic ESC (EuESC) and ectopic ESC (EcESC) from endometriosis patients. We found the collagen lattice contractile ability of EuESC was significantly stronger than that of NESC, and the cell mobility of EuESC and EcESC was significantly greater than that of NESC. Furthermore, the expression of F-actin and vinculin in NESC, EuESC and EcESC cells progressively increased, and the Rho GTPase activity, of which RhoA exhibited the highest activity, in the three cells gradually increased. Collectively, these results suggest that the mechanical characteristics of NESC, EuESC and EcESC cells exhibited progressive abnormalities. Therefore, the biomechanics of endometrial stromal cells may be a potent target for intervention in patients with endometriosis.

Keywords: Endometriosis, cell mechanics, contraction, motility, RhoA

Introduction

Endometriosis is a common, benign gynecological lesion in which endometrial stromal cells and epithelial cells ectopically implant in a location outside the uterine cavity. Clinical manifestations include dysmenorrhea, pelvic mass, and infertility and can seriously threaten the quality of life and reproductive ability of women. The classic doctrine of endometriosis maintains that endometriosis is caused by reflux menstruation or immunity, without full elucidation of the etiology. In clinical practice, endometriosis is typically treated with surgery and sex hormone drugs, but the efficacy of conservative medical or surgical treatment with preservation of ovarian function is poor, and the recurrence rate is as high as 40% [1]. Endometriosis is one of the scientific issues in the field of obstetrics and gynecology that remains to be solved, and in-depth studies of the pathophysiology of the disease are needed.

In the tissue structure of the endometrium, epithelial cells and stromal are separated by a basement membrane. Thus, although epithelial cells are not directly in contact with the vasculature, stromal cells and vascular are in direct contact. Signaling molecules, including hormones and cytokines in the blood circulation, are first in contact with stromal cells, resulting in autocrine and paracrine activities in stromal cells. These newly released signaling molecules, together with the original signal molecules, act on epithelial cells through the basement membrane, which is the main mode of crosstalk between epithelial and stromal cells [2]. Stromal cells play an important role in the growth and apoptosis of epithelial cells. In recent years, research on endometriosis has paid increased attention to the changes in endometrial stromal cell function. Clinical pathological studies have revealed that some endometriosis-like lesions have only stromal cells and no epithelial cells [3]. In clinical practice, the presence of stromal cells is also the primary basis for the diagnosis of endometriosis. Studies have discovered active contraction and migration of endometrial stromal cells in patients with endometriosis [4,5].

Cell contraction, adhesion, and migration fall into the scope of cell mechanics. The core structure of cellular mechanical movement is the focal adhesion complex. The extracellular matrix (ECM) and cytoskeleton are connected via focal adhesion complexes and integrins, and cell morphology and movement are thus altered [6]. Vinculin, a focal adhesion protein, can bind to actin and connect actin to integrin through other protein molecules, enabling the transmission of force and signal [7]. Within cells, the activated Rho-GTP enzyme RhoA, Racl, and Cdc42 allow the actin cytoskeleton to reassemble and form different cell structures, namely stress fibers, the focal adhesion complex, lamellar pseudopodia, and membrane folds [8]. In addition, the Rho-GTP enzyme also plays roles in transcriptional activity, membrane transport, and the regulation of microtubules and cell cycle, controlling cell morphology, cell migration, cytokinesis, cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesion, and cell transformation and invasion, thereby regulating the biomechanical state of cells. Small G-protein kinases such as RhoA act as one of the switches between mechanical and molecular signals [9].

This study systematically investigated the changes in the biomechanical characteristics of stromal cells in the endometrium of patients with endometriosis, and the results suggest that disorders of biomechanical characteristics of endometrial stromal cells may be a pathophysiological link that has not yet been explored in endometriosis.

Materials and methods

Clinical samples

Human endometrium and endometrial cysts tissues used in this paper were provided by Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital of Fudan University with written informed consent signed by the patients according to Declaration of Helsinki Principles. All subsequent cellular experiments were conducted in Shanghai Cancer Institute, Renji Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine and approved by the Ethics Committee of Renji Hospital Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine.

Cell culture

Primary NESC, EuESC and EcESC cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 200 mM glutamine and antibiotics (streptomycin and penicillin).

Antibodies

Rabbit anti human RhoA and mouse anti human Cdc42 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Mouse anti human Rac1 antibody was purchased from Millipore and vinculin antibody was provided by Dr. M. Aumailley, Institute Curie, Paris, France. Mouse anti tubulin antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany.

Isolation of primary endometrial stromal cells

Fresh endometrium or endometrial cysts from patients were washed with DMEM/F12 medium for three times and infused in diluted povidone iodine liquid for 1 minute, sheared to little pieces and digested with type I collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich). After that, undigested tissues and mucous were removed by filtration. The filtrate was centrifuged at 500 rpm for 5 minutes and the precipitation was suspended with DMEM medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Isolated cells were then cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere.

Collagen lattice contraction assay

Collagen gel contraction assay was done as previously described [10]. Briefly, primary NESC and EuESC cells at 90% confluent were serum-free starved overnight, detached with trypsin and counted. NESCs or EuESC cells at a density of 5 × 104 per ml were seeded onto 3.5 cm bacteriological plates (2 ml per dish) in completed growth medium supplemented with 0.3 mg ml-1 of acid-extracted collagen I from rat tail. The cells were cultured at 37°C for 45 minutes to allow collagen polymerization and the gels were released from plates by slightly tilting the plates. After 24 hours, gel contraction was photographed and gel area was measured. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times using NESC and EuESC from different individuals.

Cell migration and time-lapse video microscopy

Confluent NESC, EuESC and EcESC cells in 6 cm dishes were serum-starved overnight, detached with trypsin and suspended with 150 μl growth medium. 12 μl of this cell suspension were inoculated to the center of the 24-well plate and cultured at 37°C for 30 minutes to allow attachment. After that, unattached cells were washed away and 500 μl of growth medium was supplemented to each well. The plate was placed to the live cell station for observation and cell motility was recorded at the border of colonies by time-lapse video-microscopy for 24 hours. Images were captured every 30 min using a CCD camera. Cell movements were measured by computing the increased cell coverage area. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times using cells isolated from different individuals.

Immunofluorescence cell staining

Serum-starved NESC, EuESC and EcESC cells were seeded on cover slides in 24-well plates and incubated for 24 hours. Cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 for 1 minute. For F-actin staining, cells were incubated with phalloidin-FITC (Sigma-Aldrich) for 75 minutes at room temperature. For vincullin staining, cells were incubated with primary antibodies against vinculin, followed by an Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated secondary antibody. Immunofluorescence signals were captured using confocal microscopy (LSM 510, METALaser Scanning Microscope, Zeiss). The experiment was repeated 3 times using the three types of cells isolated from different individuals.

Western blotting and GTPase pull-down assays

GTPase pull-down assays were performed according to standard procedures as described [11]. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing condition, followed by immunoblotting with specific primary antibodies and species-specific secondary antibodies. Bound secondary antibodies were revealed by Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE).

Statistical analysis

The results were presented as the means and SDs. Statistical differences were calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

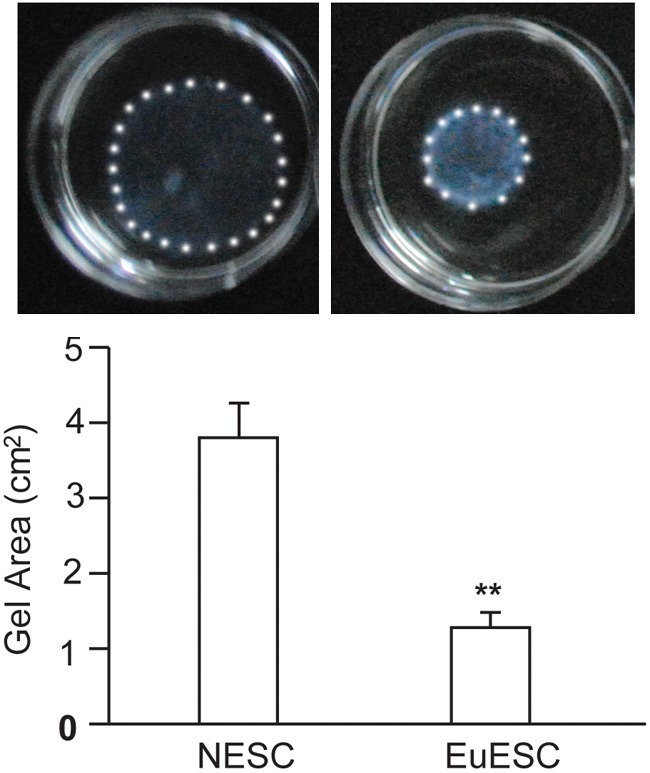

The collagen lattice contractility of EuESC was stronger than NESC

NESC and EuESC cells were isolated from healthy women and endometriosis patients as described in the Materials and Methods. EcESC cells were not included in this experiment due to the limited number of cells. After 24 hours of 3-dimensional culture, the average area of the collagen lattice containing EuESC cells was 1.27 ± 0.20 cm2, significantly smaller than that of NESC (3.84 ± 0.40 cm2), and the difference was highly statistically significant (P=0.001, indicated as **), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the area of the collagen lattice containing NESC or EuESC after 24 hours of 3-dimensional culture. The diagram above shows the representative collagen contraction of NESC and EuESC. The diagram below demonstrates the statistical analysis of the collagen lattice area. The white spots outlined the gels. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times using NESC and EuESC from different individuals.

The collagen lattice containing NESC or EuESC continued to be cultured, and the collagen lattice was progressively contracted. During the process, the area of the collagen lattice containing NESC was consistently larger than that of EuESC, until both contracted to the minimal size (grain size) at 120 hours (data not shown). This result indicated that the collagen contractility of EuESC was significantly higher than that of NESC.

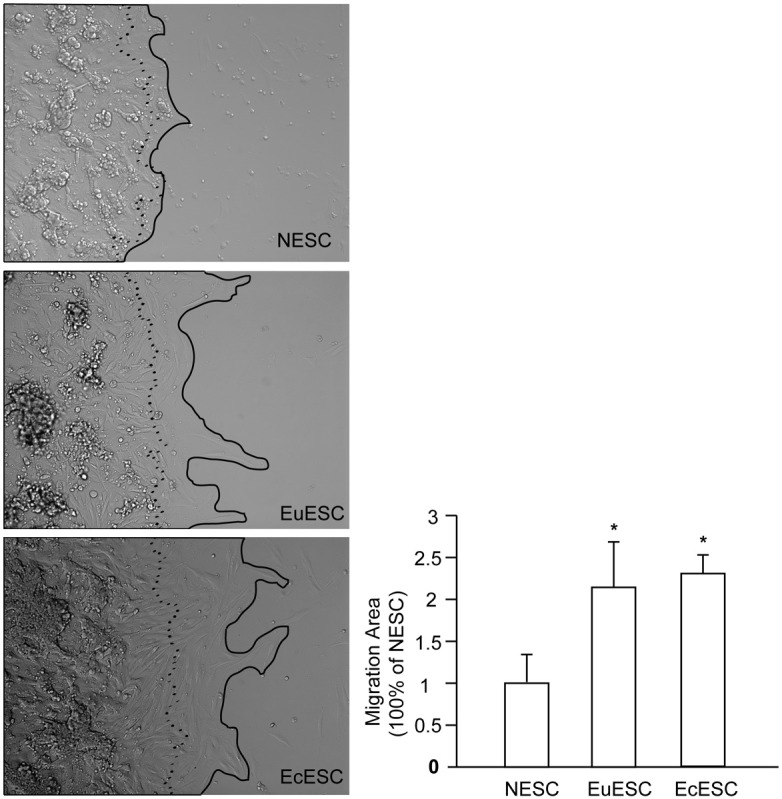

The cell motility of EuESC and EcESC was significantly greater than that of NESC

Next, we performed cell migration assay with primary NESC, EuESC and EcESCs, as described in the Materials and Methods. After 24 hours of culture, the area covered by NESC cell movement increased by 1.00 ± 0.33 × 105 μm2, significantly smaller than those of EuESC (2.15 ± 0.55 × 105 μm2) and EcESC (2.30 ± 0.23 × 105 μm2); the P values were both less than 0.05 (indicated as *), as shown in Figure 2. The area covered by EuESC was smaller than that of EcESC, though the difference was not significant.

Figure 2.

The cell motility of NESC, EuESC and EcESC. The pictures left show representative cell movement of 3 types of cells after 24 hours of culture. The dotted line outlined cell boundary at 0 hour and the black line outlined cell boundary at 24 hour of culture. The area between the lines is the increased area covered by the outward movement of the cells and was analyzed on the right panel. The experiment was performed in triplicate and repeated 3 times using NESC, EuESC and EcESC cells from different individuals.

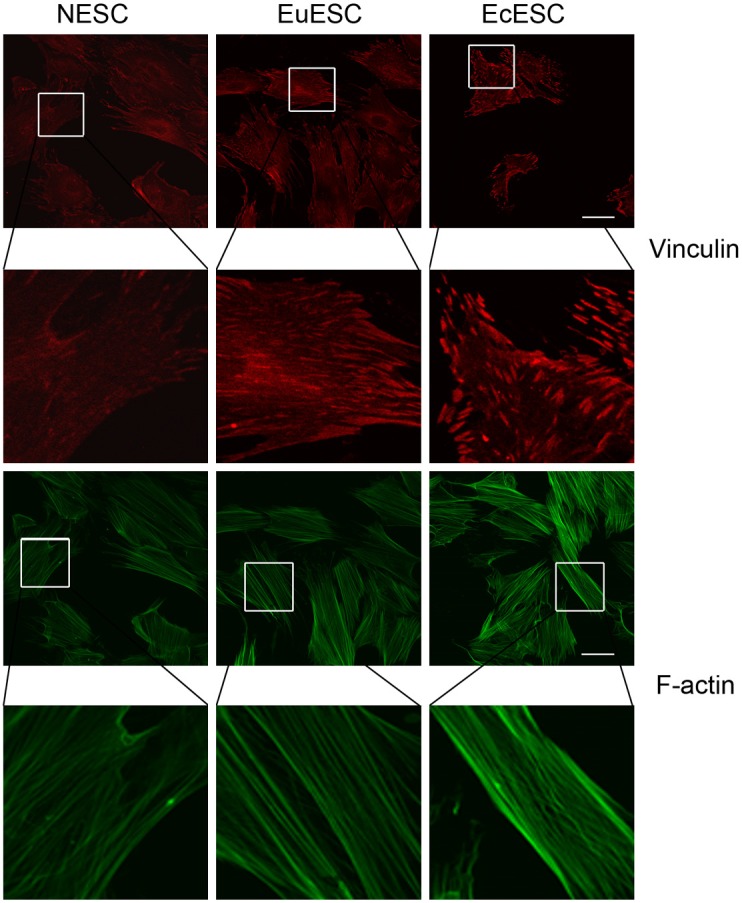

The cell tension of NESC, EuESC and EcESC progressively increased

Actin and focal adhesion complexes are integral parts of the cytoskeleton, and they represent the mechanical tension of the cells. Vinculin was detected by immunofluorescence, and the results indicate that vinculin expression also gradually increased in these 3 types of cells (Figure 3). F-actin was labeled with green fluorescent dye-labeled phalloidin, and the results indicate that in the 3 types of cells, NESC, EuESC and EcESC, the density and strength of the cell actin filaments, represented by F-actin, gradually increased (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Immunostaining of F-actin and vinculin in NESC, EuESC and EcESC. The upper 3 pictures represent phalloidin-stained green F-actin, and the lower 3 pictures represent vinculin-stained red focal adhesion complexes. In all 3 types of cells, the phalloidin and vinculin staining intensities gradually increased.

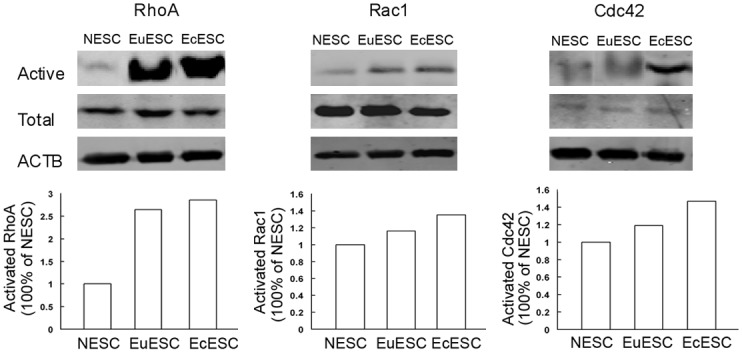

The activity of small GTPases, particularly RhoA, gradually increased in NESC, EuESC and EcESC

As shown in Figure 4, among the 3 types of small GTPases in endometrial stromal cells, the activity of RhoA was dominant and higher than that of Rac1 and Cdc42. Rac1 and Cdc42 exhibited measurable activity only in EcESC. The activity of RhoA in NESC, EuESC and EcESC gradually increased.

Figure 4.

RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42 expression in NESC, EuESC and EcESC. The first row demonstrates the expression levels of the active small GTPase, the second row shows the total GTPase expression level, and the third row demonstrates the internal reference (ACTB). The left column reports the RhoA expression. The EcESC exhibited the highest level of activity, followed by EuESC, and the activity of NESC was the weakest. The diagrams below were densitometric analysis of activated GTPases from above western images.

Discussion

The challenge in the treatment of endometriosis is the high recurrence rate. Guo [12] reviewed the literature and calculated the recurrence rate of endometriosis at 2 years after surgical treatment to be 21.5%, with a 5-year recurrence rate of 40%-50%. In the clinical studies reviewed in this study, many patients received drug treatments after surgery, but the recurrence rate remained high.

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disease, and current drug treatments are primarily anti-estrogen [13]. Among premenopausal women, long-term anti-estrogen therapy can result in perimenopausal symptoms, such as hot flashes and bone loss, which affect the patient’s quality of life [14]. The high recurrence rate may be associated with the problems with long-term anti-estrogen therapy in premenopausal patients.

Avoiding the anti-estrogen effect and finding new treatments and breakthroughs has been a topic of recent endometriosis studies. Soares et al [15] summarized the new progress of drug treatments for endometriosis. A considerable number of cytokines drugs and anti-angiogenic drugs are effective in in vitro experiments, but few have progressed to clinical trials due to many issues associated with in vivo studies.

In this study, we performed a collagen lattice contraction experiment and cell motility experiment and found that compared to NESC, EuESC exhibited stronger contractility and better mobility. During the same time frame and using the same number of cells, the area of collagen lattice containing EuESC was significantly smaller than that of NESC. In mobility experiments with live cells, at 24 hours, the area covered by the outward movement of EuESC and EcESC was also larger than that of NESC. These results were consistent with the results of literature [5,16].

Due to the limited number of cells, this study did not conduct collagen lattice contraction experiments with EcESC. According to the literature [17], EcESC exhibit stronger contractility than EuESC and NESC. The mobility of NESC, EcESC and EuESC gradually increased, which may reflect the gradual nature of the progressive development of the disease. The imbalance in the mechanical movement of the endometrial stromal cells plays an important role in endometriosis and may be involved in the development of the disease.

In our study, we observed a regular pattern of progressive disorder of the biomechanical characteristics of endometrial stromal cells in normal subjects and patients with endometriosis. In the 3 types of cells, NESC, EuESC and EcESC, the density of F-actin gradually increased, and the staining intensity of focal adhesion complexes, as shown by vinculin staining, also gradually increased. In addition, cell contractility and mobility progressively increased, and the activity of 3 types of Rho GTPases, particularly RhoA, gradually increased. In the cellular mechanical movement system, a variety of regulatory factors cause changes in the expression and activity of Rho GTPase, regulating actin polymerization into actin bundles or promoting the depolymerization of actin bundles, as well as regulating the assembly or disassembly of focal adhesion complexes. These changes alter cell tension and mobility, reflecting changes in the mechanical state [18]. Our study demonstrated significant changes in the mechanical characteristics of eutopic and ectopic endometrial stromal cells in patients with endometriosis. Cell contractility and mobility gradually increased from normal to eutopic to ectopic endometrial cells, demonstrating progressive changes. Nasu et al [19,20] found that simvastatin and heparin sodium exert an inhibitory effect on the growth of endometrial cells in vitro and may be used for the treatment of endometriosis. One mechanism underlying this effect is the inhibition of the contraction of the collagen lattice containing endometrial stromal cells in vitro.

The inhibition of mechanical movement of endometrial stromal cells may become a new method and means of intervention for endometriosis. Using inhibitors of Rho GTPase to treat animal models of endometriosis or using inhibitors of Rho GTPase and hormone drugs synergistically may help identify effective treatment options for endometriosis management.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Science Fund of China (30772310, to C.J. Xu), Program of Shanghai Subject Chief Scientist (09XD1400600, to C.J. Xu), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81101600, to X.M. Yang), the Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau Project (2010249, to R. Zhang).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Coccia ME, Rizzello F, Gianfranco S. Does controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in women with a history of endometriosis influence recurrence rate. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:2063–2069. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunha GR, Cooke PS, Kurita T. Role of stromal-epithelial interactions in hormonal responses. Arch Histol Cytol. 2004;67:417–434. doi: 10.1679/aohc.67.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyle DP, McCluggage WG. Peritoneal stromal endometriosis: a detailed morphological analysis of a large series of cases of a common and under-recognised form of endometriosis. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:530–533. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2008.064261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gentilini D, Vigano P, Somigliana E, Vicentini LM, Vignali M, Busacca M, Di Blasio AM. Endometrial stromal cells from women with endometriosis reveal peculiar migratory behavior in response to ovarian steroids. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yuge A, Nasu K, Matsumoto H, Nishida M, Narahara H. Collagen gel contractility is enhanced in human endometriotic stromal cells: a possible mechanism underlying the pathogenesis of endometriosis-associated fibrosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:938–944. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yam JW, Tse EY, Ng IO. Role and significance of focal adhesion proteins in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:520–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ziegler WH, Liddington RC, Critchley DR. The structure and regulation of vinculin. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell. 1992;70:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bustelo XR, Sauzeau V, Berenieno IM. GTP-binding proteins of the Rho/Rac family: regulation, effectors and functions in vivo. Bioessays. 2007;29:356–370. doi: 10.1002/bies.20558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu XJ, Xu MJ, Fan ST, Wu Z, Li J, Yang XM, Wang YH, Xu J, Zhang ZG. Xiamenmycin attenuates hypertrophic scars by suppressing local inflammation and the effecs of mechanical stress. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1351–60. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang ZG, Lambert CA, Servotte S, Chometon G, Eckes B, Krieg T, Lapière CM, Nusgens BV, Aumailley M. Effects of constitutively active GTPases on fibroblast behavior. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:82–91. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5416-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo SW. Recurrence of endometriosis and its control. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:441–461. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nothnick WB. Endometriosis: in search of optimal treatment. Minerva Ginecol. 2010;62:17–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palep-Singh M, Gupta S. Endometriosis: associations with menopause, hormone replacement therapy and cancer. Menopause Int. 2009;15:169–174. doi: 10.1258/mi.2009.009041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares SR, Martínez-Varea A, Hidalgo-Mora JJ, Pellicer A. Pharmacologic therapies in endometriosis: a systematic review. Fertil Steril. 2012;98:529–555. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.07.1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Osuga Y. Novel therapeutic strategies for endometriosis: a pathophysiological perspective. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2008;66(Suppl 1):3–9. doi: 10.1159/000148025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuno A, Nasu K, Yuge A, Matsumoto H, Nishida M, Narahara H. Decidualization attenuates the contractility of eutopic and ectopic endometrial stromal cells: implications for hormone therapy of endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2516–2523. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ingber DE. Tensegrity-based mechanosensing from macro to micro. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2008;97:163–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nasu K, Yuge A, Tsuno A, Narahara H. Simvastatin inhibits the proliferation and the contractility of human endometriotic stromal cells: a promising agent for the treatment of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:2097–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasu K, Tsuno A, Hirao M, Kobayashi H, Yuge A, Narahara H. Heparin is a promising agent for the treatment of endometriosis-associated fibrosis. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]