In its recent history, the physical therapy profession embarked on at least 2 attempts to create a research agenda. The first attempt occurred in December 1993 when a panel of researchers representing different clinical foci and levels of expertise was convened to develop an agenda. This effort was not as successful as hoped because the panel could not reach consensus on an agenda that would benefit the profession as a whole. The conclusion was reached that all researchers' programs of research were important; thus, no decisions were made to prescribe a program of research for the profession.

Despite this unremarkable outcome, the profession initiated a second attempt to create an agenda. Beginning in 1998, a call was placed to presidents of all components (ie, chapters and sections) of the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA), academic administrators of physical therapist education programs, and members of the Section on Research asking for nominations of individuals to participate in the development of a Clinical Research Agenda. Ultimately, 48 nominated individuals were selected.

Two meetings were held, one in the fall and the second in the winter of 1998. Additionally, an Editorial Advisory Panel (EAP) met between the 2 meetings. The EAP, as its name implies, edited the output from the first meeting and presented it for discussion during the second meeting. Subsequent to the second conference and a second round of editing by the EAP, the 128 research questions comprising the draft agenda were sent to a sample of APTA membership for final review. Subsequent to the second review and the results of an algorithm to determine which items would be maintained, 72 questions were incorporated into the final agenda. Ultimately, the Clinical Research Agenda was published in Physical Therapy1 so that it could be widely disseminated to the community of scientists and physical therapist clinicians.

Generation of a New Research Agenda

The original Clinical Research Agenda served an admirable and pragmatic purpose. It was shared with a number of funding agencies, including the Foundation for Physical Therapy and various institutes and centers at the National Institutes of Health. The Clinical Research Agenda also likely spurred junior investigators to design studies to answer those questions that were included. In all candor, there was never any formal evaluation of the Clinical Research Agenda. However, over time, the original Clinical Research Agenda became less relevant as science substantially changed and expanded during the 10-year period subsequent to its adoption. The revision is a result of the rapid changes in health care, and especially the rehabilitation environment, during the period of time subsequent to the creation of the Clinical Research Agenda.

Using a model developed by Eisenberg,2 those who developed the previous Clinical Research Agenda attempted to disregard the debates existing at that time that dealt with definitions of clinical and health services research. Rather, the agenda was developed to address the continuum covering basic science to policy research. Despite this attempt to be sufficiently broad, a number of colleagues perceived that the Clinical Research Agenda, as published, did not recognize certain areas of science, and this criticism served as an additional incentive to revise the agenda.

In part as a response to this criticism, the new agenda will be referred to as the Research Agenda. The term “clinical” will not be incorporated into its title. This decision serves 2 purposes. On a fairly superficial level, renaming the agenda avoids creating any confusion between it and the previous agenda. Perhaps more important, though, is the clear message that the revised Research Agenda emphasizes a more comprehensive perspective of physical therapy research than the manner in which the Clinical Research Agenda was perceived.

The new agenda represents an attempt to be much more specific in its aims than the original agenda. One purpose of the Research Agenda is to make it broad enough so that all areas of research along the continuum developed by Eisenberg2 are clearly included in the agenda. A second purpose is to ensure that the Research Agenda is disseminated among junior investigators to aid in the development of lines of research and, hopefully, enhance the career trajectories of these individuals to guide current and future researchers. A third purpose is to develop a list of research issues that can be shared with a large number of potential funders, not simply those who are interested in clinical research.

One additional characteristic of the new Research Agenda should be emphasized. The items of the agenda use language congruent with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF),3 acknowledging the potential advantages of such a unified and standard language and framework for the description of health and health-related states. However, the ICF is not used to the exclusion of other models of health and disability that may provide advances in knowledge for current and future work. The Research Agenda acknowledges that physical therapy researchers may investigate domains across the range included in the ICF (ie, body structures and function, activities and participation), as well as the contribution of contextual factors (ie, personal and environmental factors) to health conditions across these domains.

It must be stated that, although the Research Agenda recognizes the ICF and could potentially spur research internationally, it was designed to enhance research conducted by physical therapists in the United States. Clearly, some of the items contained in the Research Agenda may be appropriate for international researchers; however, the audience that was more important to the developers of the Research Agenda was physical therapist researchers in the United States.

Subsequent to the decision to create the Research Agenda, the best approach to development was assessed. The primary goal of any approach would be the assurance that the process for development would be as inclusive as possible. Other disciplines and professions have used a variety of strategies to develop a research agenda. These strategies varied substantially in the degree of inclusiveness. The simplest technique for creating an agenda was using a manuscript in a professional journal citing the need for a research agenda.4,5 This approach unveils an agenda quickly, but it does not meet the criterion of being inclusive.

The most frequently used strategy was to conduct a conference or workshop comprising experts in a particular area of study.6–12 The number of conference participants varied from 20 to 150 individuals deemed experts in a particular field. Although convening a requisite number of experts is an improvement on one individual issuing a “call” for a research agenda, organizing a conference, regardless of its size, does not necessarily ensure that all perspectives and interest areas of a profession are met. In fact, as reported, APTA used this strategy previously. Feedback indicated that conference participants did not represent as broad a range of perspectives as was hoped.

Although a conference or workshop was the strategy adopted most often, other methods for agenda development were used as well. Task forces or content experts were convened as a way to generate the items that would comprise an agenda. Although the work of the task forces differed across organizations, the burden for producing an agenda fell to a relatively small group of people. Some of these task forces or content experts relied on input from larger groups of individuals; others provided all input to agenda development.13–15

Finally, a modified Delphi technique has been used to develop research agendas. The number of participants varied greatly between the 2 professions that used this technique to generate opinion. One of the data collection efforts encompassed 18 individuals,17 while the second effort collected data from 80 respondents.18

Process for the Development of the Research Agenda

Any of these methods for deciding on topics to be included in the Research Agenda could have been selected. However, previous experience1 pointed out that soliciting information from the largest number of participants would be optimal. To this end, a unique data collection strategy was initiated that began with content generation through APTA sections, conferring significant responsibility on the APTA sections in the generation of content. The essential reason for initiating the process through sections was to be inclusive of the broad range of clinical content expertise across the profession and to avoid the perceived lack of breadth of the original Clinical Research Agenda. Furthermore, this process represented a unique opportunity for APTA components and its national headquarters to collaborate on a project deemed to be important by the membership.

The first phase of the process was a presentation to all section presidents outlining the goal of the initiative and soliciting their assistance. Through the president, each section was asked to provide items believed to be important to its clinical or professional area. No instructions were provided to the sections concerning how potential items were to be submitted. Sections were asked to include only those items that would correspond to those issues or conditions, and the means of addressing them, that were most essential to their respective areas. Methods for generating items varied greatly among the sections. Typically, smaller sections provided a shorter list of items generated by the president or with the assistance of a small group of members.

Larger sections used more complex methods for generating items. Typically, these methods created smaller groups of respective section members charged with the task of generating items. In some instances, these smaller subgroups acted as their own panel of experts and generated a list of items. In the case of other sections, the small group developed potential items, circulated the items among section membership, and constructed a final list based on feedback received. In the case of one section, a 3-step process was created. A number of subgroups drafted a list of items, feedback was invited among the entire membership through an online survey, changes were made to the initial list, a forum was held at APTA's Combined Sections Meeting for any interested section members, and a final list of items was developed in response to feedback obtained at the forum.

Subsequent to submission of items from the specialty sections, a 6-person Consultant Group was appointed by the APTA Board of Directors and asked to complete 2 tasks: (1) review feedback (items) submitted from the sections and (2) devise a conceptual framework to organize items that would be consistent and minimize redundancy.

The Consultant Group was selected to represent each of the content areas along the rehabilitation research continuum. Thus, members included basic scientists as well as health services researchers. They also represented the age continuum of patients treated by physical therapists. To reiterate, these group members were selected so that expertise across all areas of the Research Agenda was available when items were included. Subsequently, a representative from APTA's Section on Women's Health was added to the group to ensure that issues relevant to that section were included in the Research Agenda.

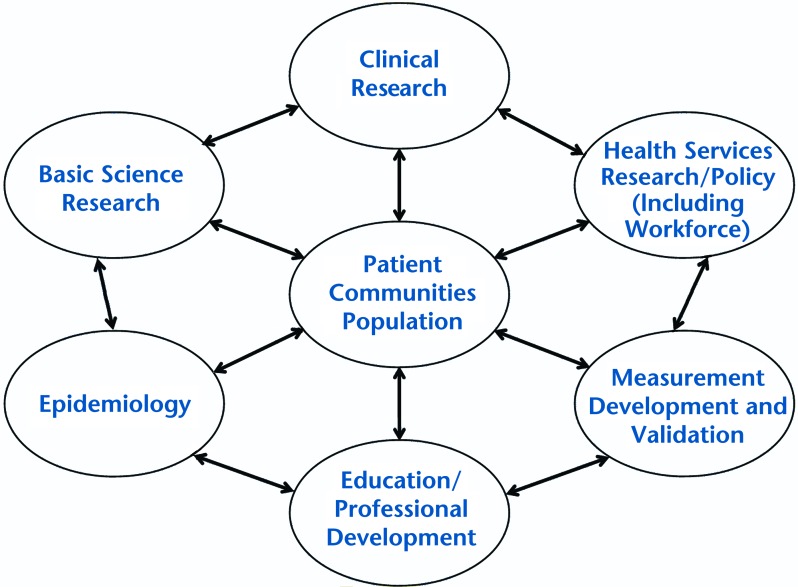

The Consultant Group began by modifying the original continuum representing all aspects of rehabilitation research that guided the development of the Research Agenda. Although the model continued to represent a continuum centered on the patient, communities, and the population, the various areas comprising the Research Agenda were expanded. Two research categories were added: “Epidemiology” and “Measurement Development and Validation.” Also, the names of 2 other areas were changed: “Policy” was added to the category “Health Services Research,” and “Professional Development” was added to the category “Education.” The inclusion of new areas and the revision of existing areas made the Research Agenda even broader than it was originally conceived. Figure 1 presents the model as it currently exists.

Figure 1.

Current model of continuum for rehabilitation research.

Sections submitted 353 items for consideration for inclusion into the Research Agenda. The Consultant Group combined similar items and placed them within the revised categories of the expanded model. This strategy allowed research topics to be phrased more generically, rather than being specific to a particular clinical area. Stating an item generically should provide the incentive for researchers from a number of different foci to address the issue.

Consider, for example, the item phrased, “Determine the effectiveness and efficacy of interventions provided by physical therapists across relevant domains.” This extremely broad item enables an individual researcher to determine which physical therapy interventions are to be provided to patients across many different types of conditions and across the life span. In addition, the outcomes of the intervention can be chosen, as appropriate, to represent the relevant domains of functioning and disability in the ICF model (ie, body structures and function, activities and participation). The following examples, representing different patient conditions, illustrate how items from the Research Agenda can be adapted for use by researchers whose lines of research are within various clinical areas.

Orthopedics: Evaluate the interactive effects of physical therapy interventions with other medical/surgical/biobehavioral interventions on clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness among patients with low back pain.

Pediatrics: Examine the efficacy or effectiveness of strengthening on spasticity, gait, and participation in school activities in children with movement disorders. Examine the role of the family as it relates to the effectiveness of physical therapy intervention. The 2 items highlighted as representing pediatrics contain added importance, as they illustrate how the Research Agenda has attempted to incorporate elements of the ICF. The 2 items cited represent the domains of body/structure/function and environmental factors.

Women's health: Evaluate the effectiveness of pelvic-floor exercises compared with or in conjunction with medical/surgical/biobehavioral interventions on clinical outcomes for women with mixed urinary incontinence.

Oncology: Determine the effectiveness of manual lymphatic drainage compared with exercise in the management of cancer-related lymphedema.

The draft of the Research Agenda, as created by the Consultant Group, then was sent to each of the section presidents and all members of the Section on Research for a final review. Section presidents were provided the opportunity of the final review, as they had been the group responsible for submitting items. The Section on Research was included in the review process because its membership comprises the individuals who will be primarily affected by the publication of the Research Agenda. Feedback was incorporated, changes were made to the final draft, and the Research Agenda was created.

Prior to the inclusion of those items comprising the Research Agenda, some important points need to be made. First, it may not be apparent to readers where diagnostic accuracy research is located within the Research Agenda. It was the intention of developers of the Research Agenda that these items be included within the section titled “Measurement Development and Validation.”

Furthermore, and of extreme importance, is the fact that research designs are intentionally not specified in the Research Agenda. The developers of the Research Agenda believed that decisions about design issues were beyond the scope of their task. Therefore, decisions about the value of randomized controlled trials as opposed to case control studies or qualitative analyses as opposed to quantitative analyses were left to the discretion of individual researchers. The Research Agenda was devised to delineate important items, not to provide advice on the design of an individual's or a group's methods.

Finally, the developers of the Research Agenda intentionally did not assess the importance or impact of any of the items included in the Agenda. A decision was made during the first meeting of the Consultant Group that citation of the importance or perhaps some ranking of the items was not warranted. It was decided that the individual researcher was better equipped to assess importance. The proof of a researcher's decision would likely be determined by the decision by a funding agency to support a particular study. Rather, the Consultant Group believed that it was not their purview to decide the importance of one study in comparison with another. What was seen as more important was the provision of a number of items that potentially could result in the creation of knowledge and an expansion of the scientific base of the profession.

Discussion

Although never formally evaluated, based on the visibility it received among various public and private funding agencies, the original Clinical Research Agenda seemed to have value. However, substantial changes have occurred in rehabilitation in the 10 years subsequent to the development of the Clinical Research Agenda. The new Research Agenda reflects those changes and expands the scope of rehabilitation research. Based on input from all sections of APTA, the Research Agenda is a document that has the potential to encourage programs of research among junior investigators and increase awareness of physical therapist scientists among funding agencies. Unlike the previous Clinical Research Agenda, an evaluation of the current Research Agenda will be undertaken to assess whether it has met its potential.

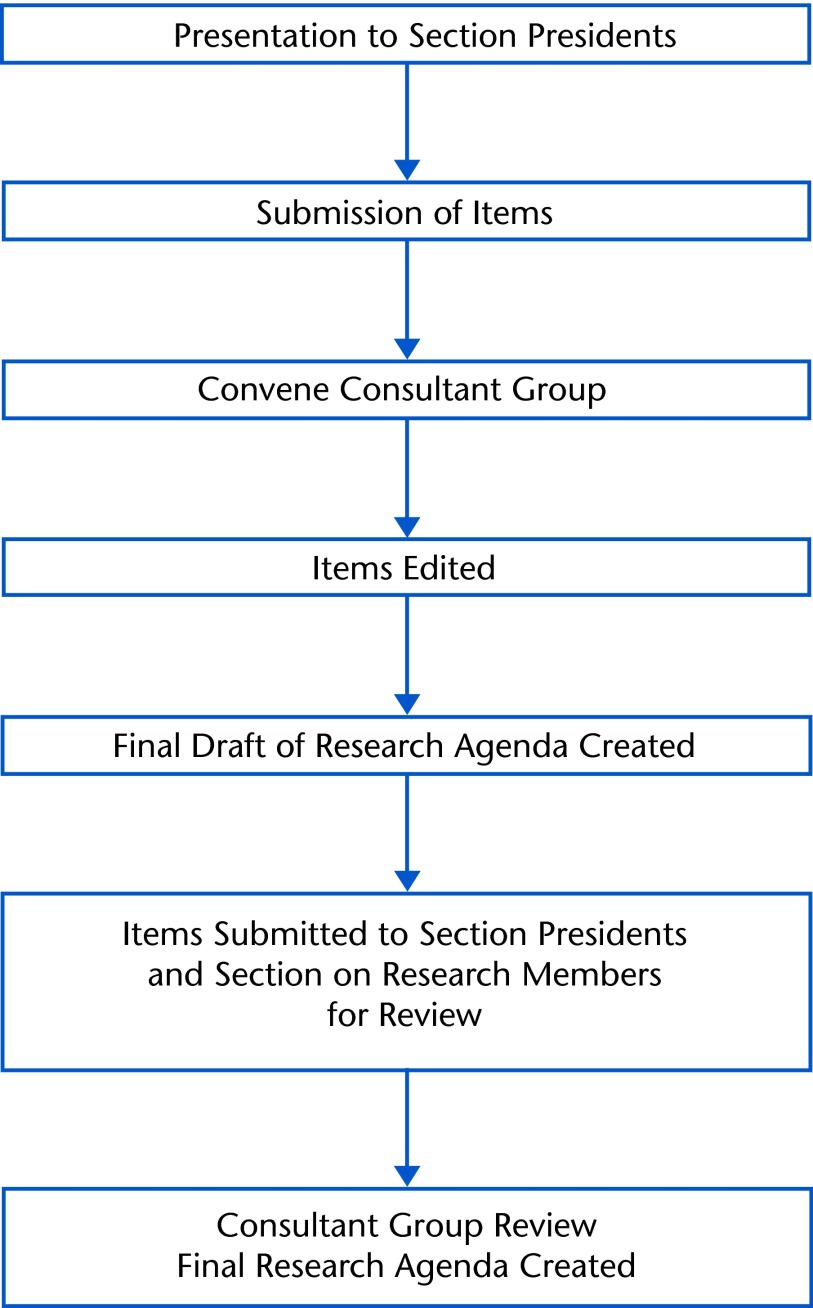

The process for the creation of the Research Agenda is described in Figure 2. The items comprising the Research Agenda are presented in the Appendix.

Figure 2.

Process for creation of the Revised Research Agenda for Physical Therapy

Appendix.

Revised Research Agenda for Physical Therapy

Basic Science Research

Identify how genetic, anatomical, biomechanical, physiological, or environmental factors contribute to excessive stress, injury, or abnormal development of body tissues and systems.

Determine if modifiable genetic, anatomical, biomechanical, physiological, or environmental factors can decrease risk of excessive stress, injury, or abnormal development of body tissues and systems.

Examine the effects of physical therapy interventions that are provided independently or in combination on cellular structural properties and physiological responses of healthy, injured, or diseased body tissues.

Investigate the factors that modify the response to physical therapy intervention and positive tissue adaptation (eg, genetic, functional, structural, psychosocial, and physiological factors).

Determine the optimal dose of physical therapy interventions (frequency, duration, intensity) to achieve optimal cellular and physiological adaptation/response of body tissues and systems.

Examine skill acquisition and motor development in individuals with movement disorders.

Examine the relationship between biomarkers and impairments in body structure and function, limitations in activity, and restrictions in participation. (Biomarkers are any tools used to identify and quantify biologic responses).

Define the role for physical therapy in the maturation and modeling of genetically engineered tissues.

Determine the mechanisms by which physical therapy interventions modify disease and age-related or injury-induced changes in normal cellular structure and function using appropriate human and animal models.

Develop new physical therapy interventions to promote tissue growth and adaptation.

Clinical Research

Determine the relationships among levels of functioning and disability, health conditions, and contextual factors for conditions commonly managed by physical therapists (eg, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health).

Develop and evaluate models of health and disability to guide the investigation, prevention, and treatment of health conditions relevant to physical therapy.

Identify factors that predict the risks of, or protection from, health conditions (injury, disorders, and disease).

Examine the impact of health promotion interventions that include the involvement of physical therapists on activity and participation of individuals with movement disorders.

Evaluate or develop effective interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of disability associated with common health conditions.

Determine the effects of interventions provided by physical therapists to address secondary prevention in patients/clients with chronic diseases (eg, diabetes, obesity, arthritis, neurological, other disorders).

Determine the physical therapist's role and impact in contemporary delivery models on prevention of diseases and their secondary side effects.

Identify technologies to assist physical therapists in developing prevention approaches that optimize outcome.

Develop and evaluate effective patient/client classification methods to optimize clinical decision making for physical therapist management of patients/clients.

Identify criteria for progression in levels of care, activity, or participation of the patient/client.

Identify thresholds for adequate physical function to optimize outcomes and prevent injury.

Identify contextual factors (eg, personal and environmental) that affect prognosis.

Identify technologies to assist physical therapists in determining patient/client classification.

Determine predictors of recovery from adverse effects associated with medical or surgical treatment.

Determine the effectiveness and efficacy of interventions provided by physical therapists across relevant domains of health.

Determine interactions among interventions provided by physical therapists.

Determine the effectiveness and efficacy of interventions provided by physical therapists delivered in combination with other interventions (eg, medical, surgical, or biobehavioral interventions).

Determine the effects of frequency, duration, intensity, and timing of interventions provided by the physical therapist.

Develop and test the effectiveness of physical therapist interventions for primary and secondary conditions or disability.

Develop and test the effectiveness of physical therapist interventions to optimize treatment outcomes for specific subgroups of patients/clients.

Develop and test the effectiveness of decision support tools to facilitate evidence-based physical therapist decision making.

Develop and test the effectiveness of methods to improve patient/client adherence to the plan of care and self-management.

Education/Professional Development

Evaluate the effect of physical therapist postprofessional specialty training on clinical decision making and patient/client outcomes.

Determine the best methods to foster career development and leadership in physical therapy.

Determine the optimal criteria for board certification.

Evaluate the effect of clinical education models on clinical outcomes, passing rates on the National Physical Therapy Examination, and employment settings after graduation.

Determine the impact of professional-level physical therapist education on professional behaviors.

Assess the effectiveness of models of professional education on clinical performance.

Determine the relationship between student cultural competency and clinical decision making.

Evaluate the effectiveness of different methods used to improve cultural competence.

Develop and evaluate the most effective methods for facilitating physical therapist acquisition and use of available information resources for evidence-based practice.

Evaluate the skills needed by practitioners to provide optimal patient/client care, patient/client advocacy, and cost-effective care.

Epidemiology

Examine the incidence, prevalence, and natural course of health conditions (disorders, diseases, and injuries) commonly managed by physical therapists.

Examine the incidence, prevalence, and natural course of impairments of body functions and structure, activity limitations, and participation restrictions associated with health conditions commonly managed by physical therapists.

Investigate the effects of contextual factors (eg, personal and environmental) on the effectiveness of interventions provided by physical therapists.

Health Services Research/Policy

Perform economic evaluation of specific physical therapy interventions.

Evaluate the effect of physical therapy service delivery models on economic and patient/client outcomes and consumer choice.

Determine the relationship between documentation and payment.

Evaluate the comparative cost and/or cost-effectiveness of specific physical therapy interventions compared with or in combination with other interventions.

Investigate factors that influence patient/client choices when selecting a health care provider or making treatment decisions.

Develop and evaluate new methods for incorporating patient/client values and expectations into the decision-making process.

Evaluate the effectiveness of shared clinical decision-making schemes between the patient/client and therapist on clinical outcomes and costs.

Establish the extent to which physical therapists deliver services in accordance with recommended guidelines for specific conditions and its impact on outcomes.

Determine disparities in the access to and provision of physical therapy and their impact on outcomes.

Examine the interaction among access, culture, and health literacy on physical therapy outcomes.

Examine the cultural competence of physical therapists and physical therapist assistants and its impact on intervention.

Develop innovative medical informatics applications for physical therapy and assess their impact on clinical decision making.

Investigate the influence of health policies on practice patterns and outcomes.

Evaluate methods to enhance adherence to recommended practice guidelines.

Assess the impact of continuity of physical therapy services on outcomes.

Describe patterns of physical therapy use and identify factors that contribute to variation in utilization.

Workforce

Examine the effects of staffing patterns on the outcomes of physical therapy.

Assess productivity of physical therapists in various settings and identify factors (eg, use of extenders, mandates) that contribute to variations in productivity.

Identify and test the best methods to assess past, current, and future demand and unmet needs for physical therapy.

Identify the demand for services among populations underserved by physical therapists.

Determine factors that contribute to the attractiveness of practicing in various settings and geographic regions.

Determine factors that contribute to the retention of physical therapists across various settings and geographic regions.

Determine the effectiveness of recruitment and retention initiatives in reducing the gap between supply and demand in various practice settings.

Identify variables that influence the decision of whether or not to enter the physical therapy profession.

Assess the impact of expanded scope of practice on supply and demand.

Investigate the relationship between the distribution of physical therapists and population health outcomes.

Examine the effects of workforce issues on career pathways (eg, participation in residency, fellowship, research training).

Examine the effects of participation in extended clinical training experiences on workforce.

Measurement Development and Validation

Develop or adapt measures of effectiveness and impact of physical therapy at the community level.

Develop new tools or refine existing tools to measure the impact of physical therapy on activity, participation, and quality of life.

Provide evidence to guide selection and interpretation of measurement tools for specific purposes, conditions, and populations.

Develop and test a minimum set of measures to evaluate the process and clinical outcomes for specific conditions and populations.

Develop reliable and valid measures of cultural competence of physical therapy providers and students.

Determine how contemporary technology (eg, ultrasound, gene array, magnetic resonance) can be used to measure the effects of injury/disease and physical therapy intervention on body structure and function.

Determine optimal measurement methods to enhance clinical decision making for specific conditions and populations.

Footnotes

All authors provided concept/idea/project design. Dr Goldstein, Dr Scalzitti, Dr Craik, Dr Dunn, Dr Irion, Dr Irrgang, Ms McDonough, and Dr Shields provided writing. Dr Goldstein and Dr Scalzitti provided data collection. Dr Goldstein, Dr Scalzitti, Dr Dunn, and Dr Irion provided data analysis. Dr Goldstein provided project management. Dr Scalzitti, Dr Craik, Dr Dunn, and Dr Shields provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

The authors acknowledge all APTA sections that were included in the development of the Research Agenda.

References

- 1. Clinical Research Agenda for Physical Therapy. Phys Ther. 2000;80:499–513 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eisenberg JM. Health services research in a market-oriented health care system [erratum in Health Aff (Millwood). 1998;17:230]. Health Aff (Millwood). 1998;17:98–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001:10–17 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen HJ. An agenda for clinical research in geriatrics. Cancer. 1997;80:1294–1301 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mohr WK, Fantuzzo JW. The challenge of creating thoughtful research agendas. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1988;12:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hawk C, Meeker W, Hansen D. The national workshop to develop the chiropractic research agenda [erratum in J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20:302]. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1997;20:147–149 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bradley BJ. Establishing a research agenda for school nursing. J Schl Health. 1988;68:53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Halfon N, Schuster M, Valentine W, McGlynn E. Improving the quality of healthcare for children: implementing the results of the AHSR research agenda conference. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(4 pt 2):955–976 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vernon H. The development of a research agenda for the Canadian chiropractic profession: report of the Consortium of Canadian Chiropractic Research Centres, November 2000. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2002;46:86–92 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lawrence DJ, Meeker WC. Commentary: the National Workshop to Develop the Chiropractic Research Agenda; 10 years on, a new set of white papers. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2006;29:690–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Heinemann AW. State of the science of postacute rehabilitation; setting a research agenda and developing an evidence base for practice and public policy: an introduction. Rehabil Nurs. 2008;33:82–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Boninger ML, Whyte J, DeLisa J, et al. Building a research program in physical medicine and rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;88:659–666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilber ST, Gerson LW. A research agenda for geriatric emergency medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:251–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cioffi JP, Lichtveld MY, Tilson H. A research agenda for public health workforce development. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10:186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castellanos VH, Myers EF, Shanklin CW. The ADA's research priorities contribute to a bright future for dietetics professionals. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:678–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]