Abstract

The benefits of integrating primary care and substance use disorder treatment are well known, yet true integration is difficult. We developed and evaluated a team-based model of integrated care within the primary care setting for HIV-infected substance users and substance users at risk for contracting HIV. Qualitative data were gathered via focus groups and satisfaction surveys to assess patients' views of the program, evaluate key elements for success, and provide recommendations for other programs. Key themes related to preferences for the convenience and efficiency of integrated care; support for a team-based model of care; a feeling that the program requirements offered needed structure; the importance of counseling and education; and how provision of concrete services improved overall well-being and quality of life. For patients who received buprenorphine/naloxone for opioid dependence, this was viewed as a major benefit. Our results support other studies that theorize integrated care could be of significant value for hard-to-reach populations and indicate that having a clinical team dedicated to providing substance use disorder treatment, HIV risk reduction, and case management services integrated into primary care clinics has the potential to greatly enhance the ability to serve a challenging population with unmet treatment needs.

Introduction

People with substance use disorders (PSUDs) carry a high rate of co-occurring health risks and medical conditions often associated with drug use, including HIV/AIDS, sexually transmitted infections, endocarditis, and chronic viral hepatitis.1–4 PSUDs are more likely than the general population to be noncompliant with medical advice, delay needed primary health care, and rely on emergency care.5 In addition, PSUDs have significantly higher rates of emergency room visits and inpatient admissions and 30-day readmissions compared to nonsubstance users.6–9 Despite the high level of overall health service utilization, the medical needs of PSUDs often go unmet,10,11 with many only utilizing medical care for emergency purposes.12,13 Since 2006, the Institute of Medicine has advocated for the collaboration and coordination among medical, mental health, and substance use disorder providers and services.14 Recent federal health reform laws support and/or mandate the integration of mental health and substance use disorder services into primary care,15 yet how to integrate efficiently and effectively is not clear.

Substance use is a serious concern for persons with disabilities and chronic health conditions16 and can lead to increased levels of health care need and service use in these populations.17 For example, in persons with HIV, substance use disorders are barriers that significantly decrease adherence to medical care,18–21 whereas treatment, specifically agonist medication for opioid dependence, results in increased adherence in people with HIV.22,23 Patients with co-occurring substance use and HIV use higher levels of emergency room and inpatient services and have longer lengths of inpatient stays than other HIV-infected persons,24,25 although opioid agonist treatment is associated with reduced acute care utilization.25–30 Yet, people living with HIV and who use injection drugs have been found to receive inadequate medical care,31,32 largely because medical care and drug treatment are traditionally delivered separately and by different providers.33 One study of a multi-site sample of HIV patients considered “hard-to-reach” found that heavy alcohol use was associated with use of emergency visits.34 Subjects in the sample who used drugs were less likely than non-users to have received optimal levels of HIV primary care and more likely to use emergency care.35 When this population was compared with patients from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study (HCSUS), a national sample of HIV-infected persons, they were found to be significantly more likely to be heavy alcohol users and significantly less likely to use ambulatory medical care services.36

While they may obtain medical care via their use of inpatient and emergency care, PSUDs also often do not receive the addiction treatment services they need.37–39 Substance use disorders are typically chronic disorders treated with acute care, yet they warrant flexible, patient-centered, longitudinal care.40 There is an unmet need for treatment of substance use disorders; one study indicated that less than 10% of PSUDs were receiving treatment.41 Among persons living with HIV who also have substance use disorders, access to substance use disorder treatment may also be limited or nonexistent. For example, the HCSUS found that of the PSUDs in the sample, only 3.4% utilized residential treatment and 5.6% percent received outpatient substance use disorder services, while only 12.4% participated in a self-help program.42 Further, if patients do receive treatment, that treatment does not commonly include medical services.34,43–45

The benefits of offering integrated primary care and substance use disorder treatment have been documented.44 Treatment for substance use disorders has traditionally been delivered within a system of care that does not include a medical component, while medical providers have not traditionally viewed substance use disorders as a medical need. Because substance use disorders have historically not been viewed as diseases, medical patients often are not screened or referred to appropriate services.44 In addition, the differences in financing substance use disorder and medical treatment can create another barrier. While medical services are typically covered through insurance, including both public and private payers, coverage of substance abuse treatment is quite variable by state.16 Some insurance plans do not cover any form of treatment, while others fund very limited services46 such as short-term detoxification and stabilization47 instead of long-term treatment. When substance abuse treatment is covered, it may be by a different entity, as substance use disorder treatment is often “carved out” of health care insurance plans,16,44,45 which separates the financing of addiction treatment from other medical services. Though the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 offers promise of support for better integration, it remains too early to tell whether integration is well implemented.48,49

Truly coordinated and integrated medical care and substance use disorder treatment programs offer a mechanism to provide unmet medical and addiction services in one setting.50 Integrated programs provide increased screening, mental health services, communication between providers, facilitated access to services, enhanced medical treatment, and improved outcomes.44,51 Linked services have been associated with decreased use of emergency and inpatient hospital services.13,27,44 Coordinated care has also been shown to increase abstinence rates27,45 as well as improve addiction-related outcomes.27

Because integrated primary medical care and substance abuse treatment has the potential to increase quality, improve outcomes, and increase access to services among the substance using population, we developed and evaluated a program of integrated care within the primary care setting for two groups of patients: HIV-infected substance users and substance users at risk for contracting HIV. A key difference between this program and more traditional integrated programs was the ability to provide buprenorphine/naloxone (BPN/NLX, also known by the brand name suboxone), an opioid agonist treatment which has been shown to be effective for improving substance use outcomes in primary care settings.52 In this qualitative study, using focus group and satisfaction survey data collected throughout the course of the program, we identify how patients view an integrated model of care, evaluate the key elements to its success and provide recommendations for other programs.

Methods

Program description

To expand and enhance the capacity for treatment of alcohol and drug dependence among HIV-infected and high-risk HIV-uninfected individuals in the setting of primary care and comprehensive HIV/AIDS treatment, Boston Medical Center (BMC), with support from the Substance Abuse Mental Health Services Administration, created the Facilitated Access to Substance Abuse Treatment with Prevention And Treatment of HIV (FAST PATH) program between February 1, 2008 and April 30, 2012. FAST PATH was implemented in two primary care sites at BMC: the Infectious Diseases (ID) clinic serving the HIV-infected population, and the General Internal Medicine (GIM) primary care clinic, where patients at risk for contracting HIV were enrolled.

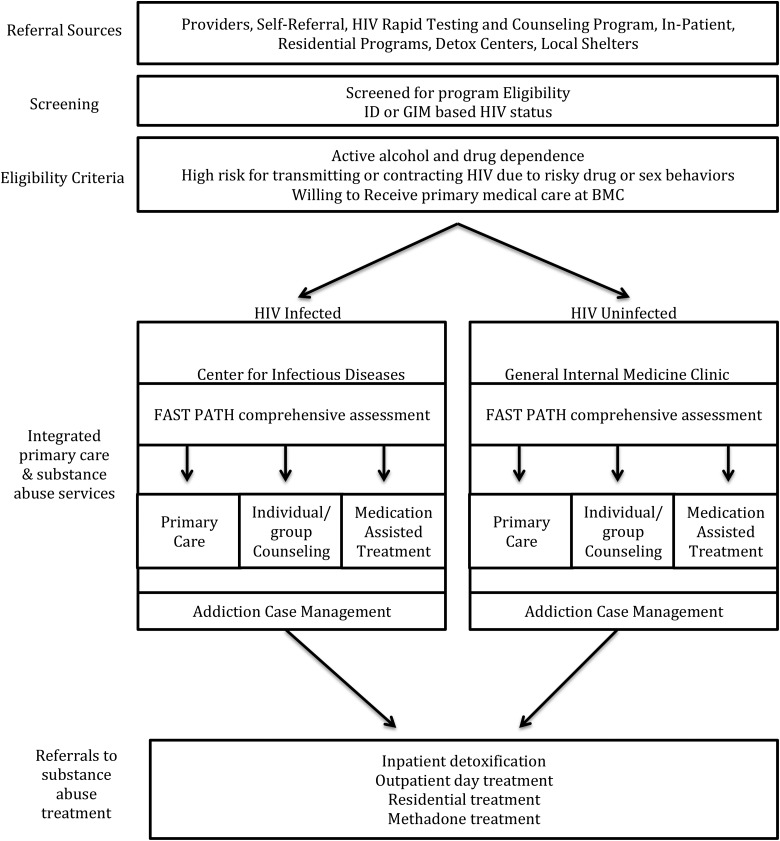

The FAST PATH program consisted of a comprehensive, multidisciplinary assessment, diagnosis, and treatment plan developed by a team that included a physician, nurse, and addiction counselor case manager. Services offered within the clinic included (a) ongoing primary care, (b) medication assisted treatment when indicated (e.g., BPN/NLX for opioid dependence; naltrexone or acamprosate for alcohol dependence), (c) HIV risk reduction counseling, (d) individual and group counseling, and (e) referral to additional substance use disorder treatment services. There were separate teams in the ID and GIM clinics. All services were designed to complement current supports already provided within the clinics. Figure 1 illustrates the program model.

FIG. 1.

FAST PATH program model and patient flow chart through the FAST PATH program.

Each FAST PATH team held weekly, half-day assessment clinics to address patients' problems across all health domains (e.g., detoxification, individual and group counseling, pharmacotherapy, primary care, mental health treatment, and HIV risk reduction services) and facilitate patients' engagement in an ongoing treatment relationship. Also addressed were ”wrap around services” such as assistance with housing, transportation, child care, food, and legal services, which were provided directly by the counselor case manager or via referrals to the appropriate community providers. FAST PATH's capacity to provide BPN/NLX was an important feature because BPN/NLX can be prescribed only by specially-certified physicians and the number of prescribers in the Boston area is limited relative to the treatment demand.

Design and data collection

In addition to participating in the clinical program, FAST PATH patients completed baseline and 6-month interviews conducted by trained research assistants. The 6-month follow-up interview included the FAST PATH program Patient Satisfaction Survey (PSS). Responses were used to assess the quality of care and services being provided, inform future directions of the program, and ensure that program goals were achieved, and patient needs were being met. In addition, a subset of patients participated in focus groups designed for program improvement. Data were collected and included in this analysis from seven focus groups held between August 2008 and January 2012 with a total of 40 FAST PATH participants. Three of the focus groups were held in GIM clinic, four were held in the ID clinic. Each included between 2–8 participants. All ID groups were mixed gender, while in GIM, one group was mixed gender, one was all males and one all females.

All focus groups were conducted by the Program Manager and Program Evaluator; each lasted approximately 1 h. We used a semi-structured interview guide that addressed the following general themes: (a) how they learned about the program; (b) how they would describe their experience in the program; (c) changes they would make to the program, including the most important things to change, not change, and the hardest element of the program: to do without; (d) how the program helped; (e) relationship between being in the program and changes in their drug or alcohol use; (f) feelings about integration between primary care and substance abuse treatment; and (g) impact of the FAST PATH program on their lives in general, including their health or social situation. The focus groups were typically led by the Evaluator, with all responses recorded in note format by the Program Manager, who also recorded direct quotations from the participants. Participants were told their responses would be anonymous, and were provided with refreshments and given a small gift card to a local pharmacy for participation.

Data analysis

Standard qualitative analytic methods were used in analysis. Both the focus group transcripts and the PSS free text responses were coded to identify key themes related to specific topic areas, for example, things they liked and did not like about the program, or areas for improvement. These themes were identified by using a process analytic framework and inductive logic to understand the focus group data. To complete our qualitative analysis, we used the Constant Comparative Method as described by Glaser and Strauss.53 According to this method, conceptual categories are developed from early responses. These initial conceptual categories are then applied to new data, and the categories are revised to reflect the new data. This method allowed us to conceptualize and categorize the diverse commentary of the focus group participants and the survey respondents in an organized manner. Themes were finalized when it was determined that they fully represented the dataset and no new themes could be identified. Coded and extracted passages were compared to identify themes related to the FAST PATH program, both overall and by clinic type (GIM or ID). Due to the fact that the same themes emerged from both the focus groups and the PSS, data were combined into a single set of key themes.

Results

Participants

Of the 265 patients who enrolled in FAST PATH, 212 (80%) completed a PSS at 6-month follow-up between July 2008 and July 2012. About 60% of FAST PATH patients were enrolled in ID clinic and 40% in GIM, which is consistent with PSS data. Table 1 describes the population that completed the PSS.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Satisfaction Survey Sample by Location (n=212)

| ID (n=127) | GIM (n=85) | Total (n=212) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Sexa | ||||||

| Male | 77 | 60.6 | 61 | 71.8 | 138 | 65.1 |

| Female | 49 | 38.6 | 24 | 28.2 | 73 | 34.4 |

| Transgender | 1 | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Race/ethnicitya | ||||||

| White | 35 | 27.6 | 49 | 57.6 | 84 | 39.6 |

| Black | 37 | 29.1 | 15 | 17.6 | 52 | 24.5 |

| Hispanic | 46 | 36.2 | 19 | 22.3 | 65 | 30.7 |

| Mixed race | 7 | 5.5 | 1 | 1.2 | 8 | 3.8 |

| Other/unknown | 2 | 1.6 | 1 | 1.2 | 3 | 1.4 |

| Mean age (SD)a | 45.5 | 8.2 | 41.2 | 11.2 | 43.7 | 9.7 |

| Substance use (at enrollment, prior 30 days) | ||||||

| Alcohol | 57 | 44.9 | 42 | 49.4 | 99 | 46.7 |

| Marijuanaa | 29 | 22.8 | 34 | 40.0 | 63 | 29.7 |

| Cocaine | 45 | 35.4 | 34 | 40.0 | 79 | 37.3 |

| Heroina | 59 | 46.5 | 52 | 61.2 | 111 | 52.4 |

| Treated with BPN/NLX by FAST PATH | 83 | 65.4 | 55 | 64.7 | 138 | 65.1 |

| Any employmenta | 7 | 5.5 | 15 | 17.7 | 22 | 10.4 |

Significant difference between sites (p<0.05)

The overall PSS sample was 65% male, 40% white, 31% Hispanic, and 25% black, Mean age was just under 44 years. When looking at characteristics by location of care, there were differences between the ID and GIM sites. Males represented less than two-thirds of FAST PATH patients in ID, but almost three-fourths of FAST PATH patients in GIM. FAST PATH GIM patients were also more likely to be White than FAST PATH ID patients, who were predominately Black or Hispanic. At enrollment, almost half reported alcohol use in the prior 30 days, 30% reported marijuana use, 37% reported cocaine use, and over half reported heroin use. By location of care, GIM FAST PATH patients were more likely to have used marijuana or heroin in the past 30 days. Approximately two-thirds of FAST PATH patients from each clinic received BPN/NLX.

Among the 40 total participants in the focus groups, half were from ID and half from GIM. To maintain anonymity, we did not collect any additional demographic or other data on the focus group participants.

Patient Satisfaction Survey (PSS)

Of the 212 participants who completed the PSS, 91% (n=192) gave an example of at least one thing they thought was best about FAST PATH, and 88% (n=187) also offered at least one comment regarding areas for improvement, although the majority of these individuals also indicated a high level of overall satisfaction.

Areas of strength

Among multiple areas of strength identified, there were several components of the program that helped them attain and maintain sobriety and stay connected with other people focused on recovery. Participants felt most strongly about their positive interactions with the program staff. In both clinics, while there were a few staff-related complaints, the majority of respondents commented favorably about the staff both in terms of their nonjudgmental, caring attitudes and their ongoing availability when needed. The following comments typified how participants felt about the staff and their support: “What kept me coming was people telling me I was doing good, they were proud of me. I really felt loved when I did not love myself. Staff are great; I'm treated with respect and like a human being.” Another participant described it as the “domino of help, circle of help that doesn't stop.” A third participant said, “Even when you mess up they don't give up on you. Other suboxone programs, you have a dirty urine, they just kick you out. Here they'll stick by you and help you work through it and get back on track.”

The second most common feature identified was the group counseling format and, in particular, both the education and the peer support they received as a result of the groups. One participant said, “Everybody (is) in the same category, don't have to be afraid to say anything because everybody is going through the same thing.” Another said, “The groups were awesome! I learned a lot from (the counselor) and the other group members.” A third said, “I loved hearing other people's struggles and giving input.”

Other frequently mentioned strengths of the program were the care management components and those things done by the staff to address a broad range of needs. Participants talked about how important it was to have multiple services in one location, including medical and preventive care, substance abuse services, and case management which helped them with concrete services, such as housing, food and SSI. Other strengths of the program identified included the individual counseling and easy access to the program in general.

Access to BPN/NLX was a major draw of the program for those who received it. A number of participants spoke about how helpful it was to get the medication on time and regularly. For many participants who had been on methadone, BPN/NLX was considered much more helpful. One participant described, “(BPN/NLX) is the best thing I've ever done. Because of it, I haven't relapsed once.”

Areas for improvement

Although most participants were happy with the program and many said that nothing could be improved and the program was “fine the way it was,” there were a broad range of ideas about how FAST PATH could improve. Among those who had ideas for improvement, they were typically not related to the overall program structure, as most participants were extremely positive about the program in general. The most common areas for improvement were ideas related to the scheduling structure and staff availability. Several respondents suggested decreasing the frequency of group counseling. While there were more comments about wanting to come in to the clinic less often, there were those who wanted more groups. For example, one participant said, “I wish there were more times for group- like 2 or 3 times a week because we talk about more than substance use, we talk about our lives.”

Groups were most frequently mentioned as an area in need of improvement both in terms of modifying the actual content and process of group meetings. While participants liked the opportunity to share stories, there were some calls for more structure in the groups and more educational groups. In terms of content, multiple participants asked for more education and information, including “more materials to read and go over and talk about.” Another participant asked for, “different topics in the groups, such as self esteem and making healthy choices…” Comments and suggestions for improving the group process from one participant included “…let everyone talk at groups. Not talking over, respect everyone. Do not want groups to be about personal stories/issues. Should be about education.” Another participant said, “Follow rules of group. Rules not to talk over someone and then not enforced- people are talking at same time and over each other. Need equal time to talk in group.” 17

Multiple participants also talked about the challenges they experienced related to getting a BPN/NLX prescription. These included feeling like they sometimes had to “jump through hoops” to get medication which frequently had to do with long wait times and convenience of prescriptions. Patients complained about having to wait hours to provide urine samples and then wait to get a prescription, which was only available at one pharmacy close to the clinic. Several patients recognized that the staff were overloaded and overtaxed and suggested increasing the number of staff as a program improvement. Patients wanted more services and staffing, including increasing the amount of individual counseling available, more appointments and time with their physicians, and more support services.

In addition to the inconvenience of the pharmacy, there were some concerns about other structural barriers, such as lack of convenience of the program in terms of distance from their homes and timing of groups during the day, which would make it difficult to work or attend to other business. One participant, who lived in a shelter stated, “Meetings can be difficult to go to and make sure I can still get a bed after the meeting.” Even though Massachusetts mandated universal healthcare coverage at the time of FAST PATH implementation, some participants reported insurance barriers as reasons for not being able to participate. One said, “My insurance needed to be approved for suboxone so I couldn't stay in the program,” while another said she left the program because she couldn't afford the insurance company's co-pay for BPN/NLX.

Focus group themes

Five overarching themes emerged from participants' feelings about and experiences with the FAST PATH program and included: (a) integration of care; (b) the use of BPN/NLX; (c) program structure; (d) counseling and education, primarily the group and group curriculum; and (e) impact on quality of life; Within each of these major themes, there were often numerous sub-themes, including both similarities and differences by clinic. The overarching themes and sub-themes are described below, with quotes to illustrate findings.

Integration of care

A number of issues related to the importance of care integration emerged from the analysis, including coordination of all medical care and substance abuse treatment; ability to get all their services in one place, often at one time, leading to easier access to care; the benefit of being treated by a team of healthcare providers rather than one individual; and the ability to address multiple medical and psychosocial issues together. There was a predominance of positive feedback related to integrated care. As one participant described it, “The process of coordinating with other health care providers is great. Many medical tests are done…all my needs are met.” Another participant spoke about the ease of access as well as the team model, “I have a whole team, they reserve appointments, you can check in and get an appointment in 2 days. I tell people I have a team taking care of me.”

For the majority of patients,the ability to get all care in a single location led to ease of care and made it more likely that patients would actually take care of themselves and not ignore medical issues when they felt needed to get BPN/NLX or methadone. One patient said, “I used to have to go here and there, back to different places, now it's much easier.” Most patients, particularly those with HIV infection, liked that they had the opportunity to take care of their chronic medical issues and their addiction at the same time, and as one patient stated, “Now I can see the doctor and go to group the same day.”

However, while the large majority of the patients really appreciated the integration of care, the requirement that they receive primary care at one of the two BMC clinics was an area of concern for some patients who had longstanding relationships with external primary care providers (PCP). This was particularly difficult for patients for whom the FAST PATH provider did not become the patient's PCP within the clinic, but served only as the BPN/NLX prescriber. One patient, who would have preferred more flexibility stated, “I had to change my primary care to Dr. X and there was confusion as to who was really my PCP, so I still see my old PCP at the clinic out of XXX. Dr. X's relationship to me is confusing.”

Another concern related to administrative issues and lack of smooth procedures for patients regarding changing PCPs. As one participant described, “The transfer over took me months because I couldn't switch my primary care doctor and I had insurance problems…so I was getting (BLN/NLX) off the street or using again in between.”

Buprenorphine/naloxone (BPN/NLX) treatment

BPN/NLX was prescribed if appropriate for opioid dependence. The FAST PATH program typically mandated patients receiving BPN/NLX engage in weekly counseling (primarily group counseling). Although not all patients were receiving BPN/NLX, for those that did, the medication was an important motivator. There were numerous positive comments about the benefit of BPN/NLX in terms of feeling better and, specifically, as a preferred alternative to methadone maintenance. Two participants explained how it had totally changed their lives. One stated, “I've been on (BLN/NLX) 3 years now. I'm more responsible at home, I work, I look forward to getting started in my day and I take the pill and it helps me get going.” The other stated, “Heroin is a waste of money; I follow my contract and am more responsible.” The medication treated withdrawal symptoms, reduced cravings and allowed people to refocus their lives on productive activities. One said, “Even when I first got on (BPN/NLX), I was still shooting dope, now I don't, I'm not running in the street, I know the dope won't do nothing for me now with the (BPN/NLX). I'm saving money, living better.” Several participants spoke of the benefits of BPN/NLX over methadone, including the idea that it did a better job of keeping them off of heroin, did not lead to any cravings and that there were no negative side effects experienced, in particular, the somnolence that some believed comes with methadone treatment.

Consistent with some of the PSS comments, the process by which the BPN/NLX prescriptions were written, the subsequent wait times to pick up prescriptions, and the requirement to receive it at one pharmacy were challenges for some patients. One participant stated, “The prescriptions have been a pain. I am worried that because I came in today I won't get my prescription on time on Wednesday. I need a set day and time that I get my prescription. The program needs to be more organized.” Another participant described, “Yeah, it's a problem. I don't like having to wait for my prescription and get it at a certain pharmacy; we have another life to live and responsibilities, there is a lot of waiting.”

Program structure

Issues related to program structure were raised by a wide range of participants, who reported on both positive and negative aspects. Almost all patients said that the requirements and structure of the program, including mandatory attendance at weekly counseling sessions (group or individual) and treatment agreements for patients receiving BPN/NLX prescriptions were difficult to maintain, but most said that overall, structure was what they needed. While a number of patients complained about the structure, there was a sense of appreciation for it and the consequences for violations. One patient stated, “I need the structure and the consequences…we are scammers. When you are sober and they tell us to call, it is good practice and teaches us responsibility.” Another said, “Nurse X has been really hard on me but she provided structure that has helped me.” One patient described the importance of structure leading to accountability, even though she was annoyed about getting medication tapered for missing appointments, despite it being part of her treatment agreement. This patient stated, “I've had a few relapses not even with heroin, I've had my script cut…for not showing up for a doctor's appointment, but I'm still here. Whatever they are doing is working.”

Although some patients complained about the requirement to attend counseling, and the consequences for skipping sessions, they also spoke specifically about the importance of the groups and the structure of the program to “keep them in line.” One participant stated, “I love getting high but I don't like the consequences. The meetings/groups keep reminding me of those consequences. The more meetings I go to the less time I have to use.”

While some participants felt that having to attend a weekly group was extremely helpful and offered them structure, others felt that it was excessive. One comment illustrating the need for weekly attendance was the following, “The group has helped me. I need to be on a full schedule…the weekly groups keep me in line along with the urines. Yes, I benefit from some of the things people talk about. I see this as a meeting, not as an obligation because an obligation makes me want to skip out. I like the small meeting size, and I come for input and knowledge.” This comment came from a patient not on BPN/NLX, and who did not need to come to group as a requirement for receiving a prescription. On the other hand, some participants felt that the requirement made it difficult to live other parts of their lives. One stated, “It would be better to have it every other week. For people who work, it's hard to be here every week. If we had an option to come twice a month, but be required to come twice a month so it's easier. If we had bad urines we could change back to come once a week.”

Counseling and education

Attendance at counseling, most commonly group counseling primarily led by the addictions clinician case managers, was a primary and mandatory component of FAST PATH for those receiving BPN/NLX. Individual counseling was available as an alternative, or to supplement group counseling, but due to the amount of counseling hours available, most patients were asked to engage in group counseling. The group counseling sessions were weekly and gender-specific in the GIM clinic at the request of program participants early on, but gender-integrated in the ID clinic. Overall, there were few comments about the individual counseling, perhaps because few focus group participants received individual counseling. It was noted as an option that could have been more available. One participant stated, “Some people have one-on-one sessions but not me, not all of us. We should all have that option, to see the counselor individually so we can talk about things we don't want to talk about or don't have time for in the group.”

Participants from GIM also received HIV risk reduction counseling. However, despite meeting the eligibility criteria of high HIV risk, the participants almost universally did not feel that HIV risk reduction counseling was helpful or a necessary component of their treatment. When asked during the focus groups whether HIV risk reduction counseling would be helpful, one participant stated, “I don't think so. I don't even want to think about relapsing. And everyone knows how to get needles from (the pharmacy) and where the needle exchange van is. I think it'd be a waste of time.” Another participant said, “We've all been through a lot of them. Being an addict, we tend to get tested more often than regular people anyway.”

There was a mix of feedback on the group curriculum and structure. Some patients enjoyed structured learning objectives, while others felt that it would be more beneficial to learn from one another's stories. This was the area in which there was the greatest divergence between the two clinics, with one having a structured curriculum with clearly identified topics for each group meeting, while the other was more open-ended with the content driven more by the individuals in the group. Participants in the open-ended groups asked for more structure and content-based education. One stated, “The groups need to have different focuses, [the staff ] needs to have more control over the topic. We need to all go around the room, change it up, get us more involved, I need to get more out of it. Sometimes I just sit here.” This theme resonated for many, with another participant saying, “The leader of the group has to direct it more, run it. Not let people veer off and only tell their own story…we want the leader to keep the group going on track.” Very strong feelings about the lack of structure were identified by one participant, who clearly missed the educational and content aspects and expected that type of structure from an addiction group. He stated, “this group is the most unhelpful one I've been too. I don't feel like I get anything I can use from the group, I have another group that I always walk away from with something I can do or think about. The group doesn't have a main goal we focus on…we had one group (session) that I did learn something on, what each substance does to your brain. This group is more about urines, this person sleeping, this one broke the rules. These topics should be for one-on-one. The group shouldn't be about people bitching about stupidity.” Yet, this reaction was not universal. A minority of participants preferred the open-ended focus and whether they preferred more or less structure in the groups, participants consistently liked the opportunity to interact with others who shared their experiences and getting support from them. Being in the group was “like a family, growing up.” Another said, “I was scared to get clean again. I like the groups and all the support…”

When the group was structured and topic-based, positive feedback predominated. There were multiple affirming comments about the topics related to relapse prevention and how the group helped with staying clean, such as “I like the group. It's cool. I like the way it is structured out. We've been working on relapse prevention, and warning signs, behaviors and all the red flags indicating a relapse. The disease makes you forget what it has done to you. It robbed me of my career. I was sober for 10 years and I relapsed. I get depressed because I did not go through with my career. The urges to use start sneaking up.” However, others liked the breadth of topics: “They teach us about the politics, the health care, everything. They teach us amazing stuff about what drugs do in your body, I love that part.”

There was strong preference for disease-specific groups and gender-specific groups among the women in the GIM clinic, but the men indicated no preference for gender-specific groups. However, the women in GIM felt strongly about this, with all women reporting positive feedback on having their own group in GIM. One woman said, “I love it being women only. We talk about things, we've all done everything and have that common bond. “ A second said, “I don't go to AA or NA because it's men and women, especially when you first come back from being on the streets and doing drugs, you are so beat down but you can't do that, you have to watch what you say. As a female, talking in front of a man, I can't share there.” For ID patients, gender-specific groups were not considered as important as being with others who were HIV positive. Comments included, “(there is the) importance of treatment with other HIV+ clients. (you) start out in a safe group, it builds confidence to share in other groups of people. I wouldn't have been as open with other people, we're all on the same page.”

Impact of FAST PATH on quality of life

Noted throughout the focus groups over the years was not just the medical and addiction treatment benefits, but also the commitment of the treatment team to improving patients' overall quality of life beyond their health. For participants, this came through primarily by providing other types of concrete support services. Participants frequently spoke of what the program staff did for them that went beyond the traditional boundaries of health care. Comments included, “All paperwork and letters are signed for things like housing and court.” Another described, “They help with housing, welfare, all the support…13 different housing letters they sent, Counselor X hand filled out every single one of them. It wasn't a matter of asking twice, they are very encouraging, they get on you to do your part, and they do their part even more than you are doing yours.” One FAST PATH participant explained how the help with services, especially housing, helped with addressing his addiction and overall quality of life, “When I got my keys to my apartment, I felt like a kid at my first Christmas; it was that kind of excitement. When you're living on the street, just to cope you gotta stay high, to stay in those shelters—they're nuthouses. It's kind of hard to do it straight. When you're in your own place, you don't think about using.”

Another major impact of FAST PATH on quality of life was the importance of the program in helping participants get clean and maintain sobriety. There were several poignant examples of how the program had changed and improved lives, including improving relationships with families, keeping participants out of jail, and moving towards living more stable and fulfilling lives. One man with HIV talked about how his health had improved and how he was living better in all facets of life: “Between group and (BPN/NLX), I'm getting help. I'm not chasing, stealing, looking for a fix. I was tired of my wife throwing me out. I'm saving money, looking better. My T-cells went up, I have an appetite now.” Another participant also explained how she was more stable financially and not putting herself at risk, “I even have a bank account now, I'm not broke, I'm not turning tricks, it feels so good to not have to live like that.”

For multiple participants, substance use had led them down a road that frequently ended in incarceration, and FAST PATH had helped participants move away from that lifestyle. Despite the challenges of staying clean, one participant described how the program helped to him stay clean and therefore out of jail: “When I get up I still want to shoot a bag sometimes, being in this program helps me. I don't want to go to jail anymore. I'm tired. I've been doing it since 1968, half my life I've been incarcerated. This program is helping to keep me out.” Another participant, who had worked hard to get clean before joining FAST PATH, explained how the program had helped her move forward: “The program has helped me get sober. I was already on the road to becoming clean. But FAST PATH played important part. I had just gotten out of jail when I started here. I'd be in jail if it weren't for this program.”

Finally, participants talked about quality of life in terms of how FAST PATH had helped them change their relationships with family members. One woman said, “I have a place to go, to share, I just celebrated my daughters 18th birthday. Dr. X reminded me that when I first got here I was crying my eyes out because I didn't know how to be a mom, now I've celebrated 4 birthdays with my daughter, she is like my best friend. When I came here I was 112 pounds and grey, now I'm healthy, things are going good for me.” Another woman who had mended her relationship with her family stated, “ My son, he was getting married, I knew I can't show up at his wedding sweating after taking a hit and I was there, it was in May, I was clean and I was glowing! Thank you God and thanks to this program.”

Discussion

In this qualitative study, we have described lessons learned from an innovative program that used multidisciplinary teams to integrate treatment for substance use disorders into primary care for patients with HIV infection and those at high risk for HIV. Findings from this study demonstrated that (a) patients recognize the benefits of integrated care as increased convenience and efficiency of receiving medical care and treatment for substance use disorders in the same place, (b) among patients with opioid dependence, agonist treatment with BPN/NLX facilitated the success of integrated treatment, (c) there was no consensus among patients about how strict the program requirements should be, (d) group counseling was a key element of successful treatment, for many, but not all patients, and topic-based groups with a structured curriculum were particularly valued, and (e) the benefits of the program, facilitated by concrete case management services, extended beyond improved medical and substance use outcomes to include quality of life through better housing, relationships with family, and general outlook. Together these findings confirm the feasibility of such programs and provide support for their promised benefits, including the efficient delivery of evidence-based treatment,

To implement FAST PATH, additional staff was hired, specifically a nurse focused on substance use-related issues, as well as addiction counselor/case managers for each clinic. While adding these staff may be difficult to sustain under traditional models of care delivery and insurance reimbursement, they are consistent with the principles behind the ACA, as well as the 2008 Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act that support the creation of patient-centered medical homes as a major tool to improve the comprehensiveness, the quality, and the efficiency of healthcare.54 A core feature of the patient-centered medical home is the integration of medical, mental health, addiction, and concrete services across the care continuum.55 The ACA legislation and the ongoing and complex needs of high-risk substance users make it likely that this type of cutting-edge model will be in high demand as providers determine how to best offer a primary care medical home that can meets the needs of especially challenging populations.

Even before the availability of office-based BPN/NLX treatment studies on the use of case management and supportive services, it was shown that these services improved medical care delivery among PSUDs.56–58 Existing federal funding for HIV primary care clinics encourages that enhanced wrap around services can be used for to support this integration.59 The integration of BPN/NLX treatment with primary care for opioid dependent-patients with HIV has been shown to be feasible in a multi-site demonstration project,60 and to successfully improve engagement in HIV clinical care in a randomized clinical trial.61 In the multi-site demonstration project, a clinical staff member, typically a nonphysician, such as nurse or counselor, who took ownership of the BPN/NLX program, was key to the success of the program.62 In FAST PATH, the nurse and counselor case managers played this role with BPN/NLX. In addition, the benefits of integrating substance use treatment with primary care are not limited to patients, but can result in increased training and potentially better care delivered by other providers in the clinic.63

Limitations of this study include those of qualitative research, including limited generalizability, due to the small sample size and selectivity of the sample, including those who enrolled in the FAST PATH program and were willing to participate in a focus group. It is likely that those individuals who participated were more engaged in the FAST PATH program, specifically the group treatment. In addition, as in any focus group, although participants were assured of confidentiality and their responses appeared to be very candid, including a range of negative comments and concerns about the program and suggestions for improvement, we cannot exclude the possibility of biased or socially desirable responses.

However, despite these limitations, our findings have important implications for clinical practice. Having a clinical team, such as FAST PATH, dedicated to providing substance use disorder treatment, HIV risk reduction, and case management services integrated into primary care clinics has the potential to greatly enhance the ability to serve what would otherwise be a difficult population with unmet treatment needs. Our results support other studies that theorize integrated care could be of significant value for hard-to-reach populations.12,13,26,25,60 HIV-infected persons are frequently marginalized from other populations, as are substance users, and studies show they are less likely to use ambulatory care.34,36 The idea of integrating primary care and substance abuse services is not only practical but also feasible based on the experiences of the FAST PATH Program. Moreover, social instability has been found to be a key component of inability to participate in primary care,64 yet this study supports the benefits of case management services found in other studies as means to enhancing engagement in medical care.56,57 In general, because more traditional primary care medical teams have limited time with patients and numerous competing priorities,65 the FAST PATH model that embraces the vital principles of integrated care and provides focused substance abuse support may among those designs best suited to address the needs of patients at greatest risk for lack of engagement in care and relapse. Additional research is needed to provide clarity on the nuanced differences between counseling formats for patients who have substance use disorders and are either HIV positive or at risk for contracting HIV, as well as to identify mechanisms to best use office-based BPN/NLX procedures for populations at the highest risk of relapse.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Stein MD. Medical consequences of substance abuse. Psychiat Clinics North Am 1999;22:351–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherubin CE, Sapira JD. The medical complications of drug addiction and the medical assessment of the intravenous drug user: 25 years later. Ann Int Med 1993;119:1017–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haverkos HW, Lange RW. (1990). Serious infections other than human immunodeficiency virus among intravenous drug abusers. J Infect Dis 1990;161:894–902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rajasingham R, Mimiaga MJ, White JM, et al. . A systematic review of behavioral and treatment outcome studies among HIV-infected men who have sex with men who abuse crystal methamphetamine. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012;26:36–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGeary KA, French MT. Illicit drug use and emergency room utilization. Health Serv Res 2000;35:153–169 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cherpital CJ. Changes in substance use associated with emergency room and primary care services utilization in the United States general population: 1995–2000. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2003;29:789–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.French MT, McGeary KA, Chitwood DD, et al. . Chronic illicit drug use, health services utilization and the cost of medical care. Soc Sci Med 2000;50:1703–1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stein MD, O'Sullivan PS, Ellis P, et al. . Utilization of medical services by drug abusers in detoxification. J Substance Abuse 1993;5:187–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walley AY, Paasche-Orlow M, Lee EC, et al. . Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. J Addiction Med 2012;6:50–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim TW, Saitz R, Cheng DM, et al. . Initiation and engagement in chronic disease management care for substance dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011;115:80–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Friedmann PD, Alexander JA, D'Anno TA. Organizational correlates of access to primary care and mental health services in drug abuse treatment services. J Substance Abuse Treat 1999;16:71–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umbricht-Schneiter A, Ginn DH, Pabst KM, et al. . Providing medical care to methadone clinic patients: Referral vs. on-site care. Am J Public Health 1994;84:207–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedmann PD, Hendrickson JC, Gerstein DR, et al. . Do mechanisms that link addiction treatment patients to primary care influence subsequent utilization of emergency and hospital care? Med Care 2006;44:8–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders Improving the Quality of Health Care for Mental and Substance-Use Conditions: Quality Chasm Series. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) 2012; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK19830/ Accessed March4, 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humphreys K, McLellan AT. A policy-oriented review of strategies for improving the outcomes of services for substance use disorder patients. Addiction 2011;106:2058–2066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bachman S, Drainoni M, Tobias C. Medicaid managed care, substance abuse treatment and people with disabilities: Review of the literature. Health Social Work 2004;29:189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith LR, Fisher JD, Cunningham CO, et al. . Understanding the behavioral determinants of retention in HIV care: A qualitative evaluation of a situated information, motivation, behavioral skills model of care initiation and maintenance. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2012;26:344–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sohler NL, Wong MD, Cunningham WE, et al. . Type and pattern of illicit drug use and access to health care services for HIV-infected people. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007;21:S68–S76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Power R, Koopman C, Volk J, et al. . Social support, substance use and denial in relationship to antiretroviral treatment adherence among HIV-infected persons. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007;17:245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Samet JH, Horton N, Traphagen E, et al. . Alcohol consumption and HIV disease progression: Are they related? Alcoholism Clin Exp Res 2003;27:862–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tobias CR, Cunningham WE, Cabral H, et al. . Living with HIV but without medical care: Barriers to engagement. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007;21:426–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wall TL, Sorensen JL, Batki SL, et al. . Adherence to zidovudine (AZT) among HIV-infected methadone patients: A pilot study of supervised therapy and dispensing compared to usual care. Drug Alcohol Dependence 1995;37:261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rosen MI, Black AC, Arnsten JH, et al. ; MACH14 Study Group. ART adherence changes among patients in community substance use treatment: A preliminary analysis from MACH14. AIDS Res Ther 2012;9:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masson CL, Sorensen JL, Phibbs CS, et al. . Predictors of medical service utilization among individuals with co-occurring HIV infection and substance abuse disorders. AIDS Care 2004;16:744–755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laine C, Hauck WW, Gourevitch MN, Rothman J, Cohen AJ, Turner BJ. Regular outpatient medical and drug abuse care and subsequent hospitalization of persons who use illicit drugs. J Am Med Assoc 2001;285:2355–2362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarz R, Zelenev A, Bruce LD, et al. . Retention on buprenorphine treatment reduces emergency department utilization, but no hospitalization, among treatment-seeking patients with opioid dependence. J Substance Abuse Treat 2012;43:451–457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedmann PD, Zhang Z, Hendrickson JC, et al. . Effect of primary medical care on addiction and medical severity in substance abuse treatment programs. J Gen Int Med 2003;18:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenbacka M, Leifman A, Romelsjo A. The impact of methadone on consumption of inpatient care and mortality, with special reference to HIV status. Substance Use Misuse 1998;33:2819–2834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laine C, Lin YT, Hauck WW, Turner BJ. Availability of medical care services in drug treatment clinics associated with lower repeated emergency department use. Med Care 2005;43:985–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stein MD, Anderson B. Injection frequency mediates health service use among persons with a history of drug injection. Drug Alcohol Depend 2003;70:159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersen R, Bozzette S, Shapiro M, et al. . Access of vulnerable groups to antiretroviral therapy among persons in care for HIV disease in the United States. Health Services Res 2000;35:389–416 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shapiro MF, Morton SC, McCaffrey DF, et al. . Variations in the care of HIV-infected adults in the United States. JAMA 1999;281:2305–2315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Cooperman NA, et al. . Strategies to improve access to and utilization of health care services and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV infected drug users. Substance Use Misuse 2011;46218–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Wong MD, et al. . Utilization of health care services in hard-to-reach marginalized HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007;21:177–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sohler NL, Wong MD, Cunningham WE, et al. . Type and pattern of illicit drug use and access to health care services for HIV-infected people. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007;21:S68–S76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunningham WE, Sohler NL, Tobias C, et al. . Health services utilization for people with HIV infection: Comparison of a population targeted for outreach with the US population in care. Med Care 2006;44:1038–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4713. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, p. 84 http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k11Results/NSDUHresults2011.pdf 2012. Accessed February25, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rockett IR, Putnam SL, Jia H, et al. . Unmet substance abuse treatment need, health services utilization, and cost: A population-based emergency department study. Ann Emer Med 2005;45:118–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dunn CW, Ries R. Linking substance abuse services with general medical care: Integrated, brief interventions with hospitalized patients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1997;23:1–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McKay JR. Continuing care research: What we have learned and where we are going. J Substance Abuse Treat 2009;36:131–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rockett IR, Putnam SL, Jia H, et al. . Unmet substance abuse treatment need, health services utilization, and cost: A population-based emergency department study. Ann Emer Med 2005;45:118–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burnam MA, Bing EG, Morton SC, et al. . Use of mental health and substance abuse treatment services among adults with HIV in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatr 2001;58:729–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parthasarathy S, Mertens J, Moore C, et al. . Utilization and cost impact of integrating substance abuse treatment and primary care. Med Care 2003;41:357–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samet JH, Friedmann P, Saitz R. Benefits of linking primary medical care and substance abuse services. Arch Int Med 2001;161:85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Lu Y. Integrating primary medical care with addiction treatment. JAMA 2001;286:1715–1723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Batki SL, Sorensen JL. Care of injection drug users with HIV. HIV InSite Knowledge Base Chapter. 1998. Retrieved from http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite.jsp?page=kb-03&doc=kb-03-03-06

- 47.McLellan TA, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness. JAMA 2000;284:1689–1695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Azzone V, Frank RG, Normand S, Burnam MA. Effect of insurance parity on substance abuse treatment. Psychiatr Serv 2011;62:129–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.United States Department of Labor The mental health parity and addiction equity act of 2008. Retrieved October10, 2010, from http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/newsroom/fsmhpaea.html

- 50.Walley AY, Tetrault JM, Friedmann PD. Integration of substance use treatment and medical care: A special issue of JSAT. J Substance Abuse Treat 2012;43:377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Padwa H, Urada D, Antonini VP, Ober A, Crèvecoeur-MacPhail DA, Rawson RA. Integrating substance use disorder services with primary care: The experience in California. J Psychoactive Drugs 2012;44:299–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Moore VA, Sullivan LE, O'Connor PG, Schottenfeld RS. Counseling plus buprenorphine-naloxone maintenance therapy for opioid dependence. New Eng J M 2006;355:365–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glaser BG, Strauss AL. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Piscataway, New Jersey: Aldine Publishing; 1967 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rich E, Lipson D, Libersky J, Parchman M. Coordinating Care for Adults With Complex Care Needs in the Patient-Centered Medical Home: Challenges and Solutions. 2012 White Paper (Prepared by Mathematica Policy Research under Contract No. HHSA290200900019I/HHSA29032005T). AHRQ Publication No. 12-0010-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; http://pcmh.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt/community/pcmh__home/1483/PCMH_Home_Papers%20Briefs%20and%20Othe%20Resources_v2 Accessed February22, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larson EB, Reid R. The patient-centered medical home movement: Why now? JAMA 2010;303:1644–1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Magnus M, Schmidt N, Kirkhart K, Schieffelin C, Fuchs N, Brown B, Kissinger PJ. Association between ancillary services and clinical and behavioral outcomes among HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2001;15:137–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson AS, Blankenship KM, Selwyn PA, et al. . Evaluation of an innovative program to address the health and social service needs of drug-using women with or at risk for HIV infection. J Commun Health 1998;23:419–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rajabiun S, Mallinson RK, McCoy K, et al. . “Getting me back on track”: The role of outreach interventions in engaging and retaining people living with HIV/AIDS in medical care. AIDS Patient Care STDs 2007;21:S20–S29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Health Resources and Services Administration 2012. Part A: Grants to Emerging Metropolitan and Transitional Grant Areas. http://hab.hrsa.gov/abouthab/parta.html Accessed February22, 2013

- 60.Weiss L, Egan JE, Botsko M, et al. . The BHIVES collaborative: Organization and evaluation of a multisite demonstration of integrated buprenorphine/naloxone and HIV treatment. J Acq Immune Def Syndromes 2011;56:S7–S13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lucas GM, Chaudhry A, Hsu J, et al. . Clinic based treatment of opioid-dependent HIV-infected patients versus referral to an opioid treatment program: A randomized trial. Ann Int Med 2010;152:704–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weiss L, Netherland J, Egan JE, et al. . Integration of buprenorphine/naloxone treatment into HIV clinical care: Lessons from the BHIVES collaborative. J Acq Immune Def Syndromes 2011;56:S68–S75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sullivan LE, Tetrault J, Bangalore D, et al. . Training HIV physicians to prescribe buprenorphine for opioid dependence. Substance Abuse 2006;27:13–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rebholz C, Drainoni M, Cabral H. (2009). Substance use and social stability among at-risk HIV-infected persons. J Drug Issues 2009;30:851–870 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yarnall KSH, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: Is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health 2003;93:635–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]