Abstract

Extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions play a vital role in cell morphology, migration, proliferation, and differentiation of cells. We investigated the role of ECM proteins on the structure and function of human embryonic stem cell–derived retinal pigment epithelial (hESC-RPE) cells during their differentiation and maturation from hESCs into RPE cells in adherent differentiation cultures on several human ECM proteins found in native human Bruch's membrane, namely, collagen I, collagen IV, laminin, fibronectin, and vitronectin, as well as on commercial substrates of xeno-free CELLstart™ and Matrigel™. Cell pigmentation, expression of RPE-specific proteins, fine structure, as well as the production of basal lamina by hESC-RPE on different protein coatings were evaluated after 140 days of differentiation. The integrity of hESC-RPE epithelium and barrier properties on different coatings were investigated by measuring transepithelial resistance. All coatings supported the differentiation of hESC-RPE cells as demonstrated by early onset of cell pigmentation and further maturation to RPE monolayers after enrichment. Mature RPE phenotype was verified by RPE-specific gene and protein expression, correct epithelial polarization, and phagocytic activity. Significant differences were found in the degree of RPE cell pigmentation and tightness of epithelial barrier between different coatings. Further, the thickness of self-assembled basal lamina and secretion of the key ECM proteins found in the basement membrane of the native RPE varied between hESC-RPE cultured on compared protein coatings. In conclusion, this study shows that the cell culture substrate has a major effect on the structure and basal lamina production during the differentiation and maturation of hESC-RPE potentially influencing the success of cell integrations and survival after cell transplantation.

Introduction

The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is a monolayer of polarized and pigmented cells located between the neural retina and the choriocapillaris. RPE plays a central role maintaining the proper function of the retina and its photoreceptors.1 Dysfunction or irreversible damage of RPE cells leads to impairment and death of photoreceptors leading to progressive loss of vision in degenerative retinal diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD).2,3

AMD is an increasing cause of blindness in the elderly. Phenotypically, AMD can be divided into two main forms: dry (atrophic) and wet (exudative) types and further subdivided into early and late-stage diseases. However, cure for AMD and especially its dry form is lacking.2,3 Cell transplants of human embryonic stem cell (hESC)–derived RPE (hESC-RPE) cells are currently under clinical trials for the treatment of the dry form of AMD (80% of total AMD cases) and Stargardt's disease.4 hESCs are considered to be an excellent, reproducible cell source in regenerative medicine due to their differentiation potential and indefinite proliferation capacity.5 Several research groups have demonstrated differentiation of functional RPE cells from human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs).6–10 Moreover, cell transplantation experiments in animal models of retinal degeneration have demonstrated improvement in visual function after injection of hPSC-RPE cells.11–13 However, the effect is eventually lost, likely due to inefficient cell attachment and integration of the transplanted cells with the retina and choroid. Grafting of intact and polarized RPE cell sheets, instead of cell injections, is considered as a more promising transplantation strategy.14–17

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is a dynamic and complex environment that interacts with cells through cell surface receptors such as integrins.18,19 Apart from the mechanical support and its role in cell adhesion, ECM binds soluble factors and regulates their distribution and presentation to cells.20 These cell–matrix interactions play an important role in cell morphology, migration, proliferation, and differentiation.19,21,22 The basal membrane of RPE cells rests on a specific pentalaminar ECM sheet called Bruch's membrane (BM). BM is an elastin- and collagen-rich ECM that regulates the reciprocal exchange of biomolecules, nutrients, oxygen, fluids, and metabolic waste products between the retina and blood circulation. The basement membrane of RPE is the outermost layer of the BM, and it mainly consists of collagen type IV (COL IV) laminin (LN), fibronectin (FN), hyaluronic acid, heparan sulfate, and chondroitin/dermatan sulfate.23 Primary RPE cells are influenced by their ECM and abnormal ECM assembly can result in altered structure and functions, and engage in disease states.24–31 The composition of human BM alters with age, and changes in BM structure have also been shown to be associated with pathological processes: cross-linking of collagens, higher collagen I (Col I) expression, increase in thickness, and reduction of elasticity and permeability of the BM have been shown to be related to AMD pathology.23,31,32 Moreover, there is evidence that BM fragmentation can trigger proinflammatory responses that might accelerate AMD process.33–35 In addition to BM modifications, drusen deposits, a hallmark of AMD, accumulate between the RPE and BM. Drusens are rich in ECM proteins such as vitronectin (VN) and many inflammatory markers.23,33,36,37 Thus, one of the important tasks of transplanted hESC-RPE is to produce sufficient ECM to restore the functions of the damaged BM if no BM mimicking non-biodegradable biomaterial is used with cells.16,17

Previously, it has been shown that ECM affects the early stage differentiation of hPSCs into neural progenitors and neurons,38 retinal progenitor cells,39,40 and RPE cells.41 In addition, different ECM proteins have been used in differentiation of hESC-RPE.42 Most of the current hPSC-RPE differentiation protocols utilize either xeno-derived substrates, such as Matrigel™,43,44 gelatin,4,12 and human-derived ECM proteins,10,16 as attachment and culture matrices.42 However, little is known about the effects of the ECM proteins on maturation of hESC-RPE epithelium, its barrier properties, and fine structure. Moreover, there is lack of knowledge about the self-produced basal lamina of hESC-RPE cells grown on different protein coatings. We hypothesized that ECM proteins abundant in healthy native RPE basement membrane, such as Col IV and LN, would be superior in supporting the differentiation and maturation of hESCs to RPE cells. Therefore, in this study, we compared the effect generated by components found in the native BM on hESC-RPE differentiation and maturation. Our choice of proteins was based on the concept of finding a simple, effective, xeno-free, and eventually good manufacturing practice (GMP)–compatible matrix for hESC-RPE differentiation. hESCs were differentiated and maturated into RPE cells in adherent differentiation cultures on several xeno-free, human-sourced ECM protein coatings. Matrigel (MG) was tested along with the human matrices for comparison as it is so widely used.

Materials and Methods

Human embryonic stem cells

Previously derived hESC line Regea 08/023 (46, XY) was used in this study.45 The undifferentiated hESCs were cultured on γ-irradiated (40 Gy) human foreskin fibroblast feeder cells (CRL-2429™; ATCC, Manassas, VA) in serum-free conditions described previously.10 The culture medium was changed five times a week and undifferentiated colonies were manually passaged onto new feeder cells once a week.

Differentiation of hESCs to RPE cells

hESCs were differentiated to RPE cells on following ECM protein and commercially available substrates: Col I, Col IV, and LN from human placenta (all 5 μg/cm2; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), FN from human plasma (5 μg/cm2; Sigma-Aldrich), VN from human plasma (0.5 μg/cm2; Sigma-Aldrich), xeno-free CELLstart™ (CS; 1:50; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), and growth factor reduced BD Matrigel (MG; 30 μg/cm2; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). The purified human ECM proteins were chosen as they are all present in native BM23 and provide xeno-free, clinically compliant matrices for hPSC-RPE support. We have previously used Col IV for enrichment and maturation of hPSC-RPE10 and it was thus chosen as reference matrix for comparisons. CS is a xeno-free, defined, and cGMP-produced commercial hPSC matrix, while MG that is a mouse-tumor-derived ECM matrix is commonly used for hPSC-RPE differentiation and maintenance.39,44,46,47 The substrates were used in concentrations recommended by the manufacturer. The initial coating concentrations recommended for LN (2 μg/cm2) and VN (0.2 μg/cm2) were found insufficient in our preliminary tests (data not shown) and thus were used as higher concentrations. Six-well cell culture plates (Corning® CellBIND®; Corning, Inc., Corning, NY) were coated with the substrates for 3 h at 37°C and rinsed twice with Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; Lonza Group Ltd., Basel, Switzerland). Undifferentiated hESC colonies were manually plated to the protein coating and allowed to differentiate in RPEbasic medium consisting of the same reagents as the medium used for maintaining hESCs with the modifications of 15% KnockOut™ Serum Replacement (KO-SR) and no basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF).10 RPEbasic medium was changed three times a week.

After 45 days of differentiation, the pigmented areas were manually cut under a light microscope with a lancet into small pieces and detached with a needle. The detached pieces were replated to the same coating for enrichment of pigmented cells. For maturation, the hESC-RPE cells were replated after 98 days of differentiation to 0.3-cm2 BD Falcon cell culture inserts (BD Biosciences), precoated with each substrate. The hESC-RPE cells were dissociated to single cells with 1× Trypsin-EDTA (Lonza Group Ltd.), filtered through BD Falcon cell strainer (BD Biosciences), and seeded at density of 2.0×106 cells/cm2. The cells were cultured on inserts for 42 days (a total of 140 days of differentiation).

Analysis of pigmentation

The appearance of the first pigmentation on each coating was followed daily by microscopic inspection and recorded. The data were collected from five individual differentiation experiments.

The degree of pigmentation after 140 days of differentiation was analyzed by capturing images of randomly selected locations on cell culture inserts with Nikon Eclipse TE200S phase-contrast microscope (Nikon Instruments Europe B.V., Amstelveen, Netherlands). In each experiment, the light exposure settings and illumination were maintained as constant between the coatings. One to three images from four independent differentiation experiments were analyzed. These analyzed images were taken with 20× objective. The degree of pigmentation was quantified with Image J Image Processing and Analysis Software (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/index.html) through pixel intensity normalization. Inverse of pixel intensities was calculated in order to illustrate the density of pigmentation by subtracting the normalized pixel intensity from the maximum pixel intensity value for 8-bit grayscale images. To eliminate changes in different light exposures between experiments, the inverse pixel intensities in each experiment were normalized against Col IV.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

Differences in relative expression levels of paired box gene 6 (PAX6) and microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF) genes were studied with quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) after 28 days of differentiation. Further, the expression of genes coding for RPE-specific proteins bestrophin (BEST), cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein (CRALBP), receptor tyrosine kinase MerTK (MERTK), and retinal pigment epithelium specific protein 65 kDa (RPE65) and genes encoding for ECM proteins collagen type IV alpha-1 (COL4A1), fibronectin 1 (FN1), laminin subunit alpha-1 (LAMA1), and laminin subunit alpha-5 (LAMA5) was analyzed after 140 days of differentiation. hESCs differentiated on each coating were lysed to lysis buffer RA1 with Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) (both from Macherey-Nagel, GmbH & Co, Düren, Germany) or β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at −70°C. Samples were collected from four individual differentiation experiments. A sample of undifferentiated hESCs was used as reference.

Total RNA was extracted using NucleoSpin XS and NucleoSpin® RNA II kits (both from Macherey-Nagel, GmbH & Co) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quality and concentration of RNA were examined with NanoDrop-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). Two hundred nanograms of RNA was synthesized to complementary DNA (cDNA) with high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Inc., Foster City, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol in the presence of a MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase and an RNase inhibitor. The synthesis was performed in PCR MasterCycler (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, Germany) with the following cycle: 10 min at 25°C, 120 min at 37°C, 5 min at 85°C, and finally cooled down to 4°C.

TaqMan® gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) with FAM labels were used for PCRs: PAX6 (Hs00240871_m1), MITF (Hs01115553_m1), BEST (hs00959251_m1), CRALBP (hs00165632_m1), MERTK (hs00179024_m1), RPE65 (hs01071462_m1), COL4A1 (Hs00266237_m1), FN1 (Hs00365052_m1), LAMA1 (Hs00300550_m1), and LAMA5 (Hs00245699_m1). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Hs99999905_m1) was used as an endogenous control. cDNA was diluted 1:5 in RNase-free water and 3 μL of dilution was added to the reaction (total reaction volume 15 μL). Samples and no-template controls were run as triplicate reactions using the 7300 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Inc.) as follows: 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C, and 40 cycles of 15 s at 95°C, and 1 min at 60°C. Results were analyzed using 7300 System SDS Software (Applied Biosystems, Inc.). Based on the Ct values given by the software, the relative quantification of each gene was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method.48 The values for each sample were normalized to expression levels of GAPDH. The expression level of undifferentiated hESC sample was set as the calibrator for the early eye field markers PAX6 and MITF, whereas the expression level of Col IV sample was set as the calibrator for the mature RPE markers and genes coding for ECM proteins (fold change equals 1).

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction

The expression of pluripotency markers octamer-binding transcription factor (OCT3/4) and Nanog was studied with reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) after 140 days of differentiation. Total RNA was extracted and 40 ng was reverse transcribed to cDNA as described previously. RT-PCR was carried out using 1 μL of cDNA as template. Undifferentiated hESCs (Regea 08/023) were used as positive control. Detailed protocol and primer sequences have been previously published.10

Immunofluorescence

The protein expression and localization was investigated with immunofluorescence (IF) staining after 140 days of differentiation as previously described.10 The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-BEST 1:400, mouse anti-CRALBP 1:600, mouse anti-Na+/K+ATPase 1:100, rabbit anti-LN 1:200 (all from Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), mouse anti-FN 1:500 (Chemicon), mouse anti-Col IV 1:100 (Neomarkers), and mouse anti-zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1) 1:250 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:800: Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG and goat anti-rabbit IgG, and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG and donkey anti-mouse IgG (all from Molecular Probes, Life Technologies). 4′,6′-Diamidino-2-phenylidole (DAPI) included in the mounting media was used for staining the nuclei (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA). To verify that the protein detected in IF staining was secreted by the cells, we carried out immunostainings of empty Col IV, FN-, and LN-coated cell culture inserts before seeding cells to distinguish between the newly secreted ECM molecule and the ECM molecules in the coated cell culture insert. Empty cell culture insert without the ECM coating was used as negative control. Images were taken with Olympus BX60 microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) or LSM 700 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) using a 63×oil-immersion objective. Images were edited using ZEN 2011 Light Edition (Carl Zeiss) and Adobe Photoshop CS4.

Transepithelial resistance

Transepithelial resistance (TER) of the hESC-RPE layers cultured on substrate-coated inserts was measured after 140 days of differentiation to study integrity and barrier properties of the epithelium. RPEbasic culture medium was replaced with DPBS and measurements were carried out with a Millicell electrical resistance system volt-ohm meter (Merck Millipore, Darmstad, Germany). TER values (Ω·cm2) were calculated by subtracting the value of a similarly treated substrate-coated insert without cells from the result, and by multiplying the result by the surface area of the insert. TER values were obtained from five individual differentiation experiments with multiple parallel samples for each coating. All measurements were conducted twice and average values were calculated.

Transmission electron microscopy

After 140 days of differentiation the hESC-RPE cells on substrate-coated inserts were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) prepared in 0.1 M phosphate buffer for 2 h at room temperature (RT) following incubation in 0.1 M phosphate buffer overnight at RT. Thereafter, the samples were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (Ladd Research, Williston, VT) for 1 h at RT and dehydrated through a graded series of acetone (J.T. Baker; Avantor Performance Materials, B.V. Deventer, Netherlands): 70% acetone, 94% acetone, and absolute acetone. The samples were then infiltrated in a 1:1 mixture of absolute acetone and epoxy resin (Ladd Research) for 1.5 h at RT, embedded in pure epoxy resin overnight at RT, and polymerized for 48 h at 60°C. Toluidine blue staining of the semithin sections was used to select the position for making the thin sections. Thin sections were stained with 1% uranyl acetate for 30 min and with 0.4% lead citrate (Fluk, Steinheim, Switzerland) for 5 min. Samples were examined and imaged with JEM-2100F transmission electron microscope (TEM; Jeol Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Cell and basal lamina thickness on substrates was determined from the TEM images with Image J Image Processing and Analysis Software. The thickness of four to five randomly chosen cells and self-assembled basal lamina underneath these cells was determined from each substrate.

Western blotting

The ECM protein expression was studied further after 140 days of differentiation with western blotting on Col IV, FN, LN, and MG coatings. The samples were washed twice with ice-cold DPBS, and lysed into 2× Laemmli buffer consisting of 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8 at 25°C) (Trixma base; Sigma-Aldrich), 2% w/v sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), 17% glycerol (Merck Millipore), 0.01% w/v bromophenol blue (Sigma-Aldrich), and 1.43 M β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Complete Mini protease inhibitor (Roche Diagnostics Gmbh, Mannheim, Germany) was added to the samples to prevent degradation. The samples were run in 7.5% SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and then blotted to Amersham Hybond™-P PVDF Transfer membranes (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom) in semidry conditions. Blocking was done with 5% fat-free dry milk in 0.05% Tween20 (Sigma-Aldrich) at RT for 1 h. Thereafter, membranes were incubated in primary antibody dilutions rabbit anti-LN (1:1000; Abcam), mouse anti-FN (1:8000; Merck Millipore), and mouse anti-Col IV (1:1000; Merck Millipore) overnight at +4°C. All primary antibodies were diluted in 5% milk solution with 0.05% Tween20. After primary antibody incubation, the membranes were washed in 0.5% Tween20 in tris-buffered saline (TBS), 0.1% Tween in TBS, and 0.05% Tween in TBS. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Santa Cruz, Dallas, TX) and anti-rabbit IgG were diluted in 5% milk solution with 0.05% Tween20 and incubated at RT for 1 h. Protein–antibody complexes were detected using Amersham™ ECL™ Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare). Thereafter, the membranes were stripped in stripping buffer consisting of 0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol, 2% w/v SDS, and 62.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8 at 25°C) for 30 min at +56°C. Each stripped membrane was blocked and stained with loading control mouse anti-β-actin (1:5000; Santa Cruz) for 1 h at RT. Immunoblotting and detection for stripped membranes was carried out as described previously.

The ECM protein expression on each protein coating was quantified with band area calculation in Image J Image Processing and Analysis Software. The expression of the secreted ECM protein was compared with the loading control β-actin from the same lane in the membrane. These protein/β-actin ratios were calibrated against Col IV samples (protein/β-actin ratio equals 1) in order to carry out relative comparison between the different protein coatings.

Phagocytosis of photoreceptor outer segments from rat retinal explants

The phagocytic properties of hESC-RPE monolayers on Col IV-, FN-, LN-, CS-, and MG-coated surfaces were studied using rat retinal explants after 184 days of differentiation. The use and handling of the animals was conducted according to the Finland Animal Welfare Act of 1986, the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and the guidelines of the Animal Experimentation Committee. Non-dystrophic Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) rats at the ages 15 and 18 weeks were euthanized using carbon dioxide inhalation following cervical dislocation. The eyes were detached carefully and immersed in Ames medium (Sigma-Aldrich) buffered with sodium bicarbonate and equilibrated with a gas mixture of 5% CO2 and 95% O2, and the retinas were detached from hemisected eyes. The isolated rat retinal explants were placed on the hESC-RPE monolayers with the photoreceptors facing the cells in B27/N2 medium consisting of Neurobasal A, 1% N2, 2% B27, 2 mM glutamax (all from Gibco, Life Technologies), and 100 U/mL penicillin/streptomycin. The retina was transferred on the hESC-RPE monolayers on top of a small piece of lens paper. The retinal explants were cocultured with hESC-RPE monolayers for 2 days at +37°C and 5% CO2. Medium was added daily to prevent the drying of the explants. After 2 days of coculture, the retinas were gently removed and the hESC-RPE monolayers were analyzed by IF staining. Rat rhodopsin was visualized using rat anti-Opsin antibody (O48869; Sigma-Aldrich) and actin was detected with 0.02 μg/mL phalloidin-TRITC (P1951; Sigma-Aldrich). Donkey anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies) diluted 1:800 was used as secondary antibody. IF staining was performed as described previously. IF images of phagocytosis were visualized with Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope using sectional scanning.

Ethical issues

The Institute of Biomedical Technology at University of Tampere has the approval of the National Authority for Medicolegal Affairs Finland (TEO) to study human embryos (Dnro 1426/32/300/05) and a supportive statement of the Ethical Committee of the Pirkanmaa Hospital District to derive, culture, and differentiate hESC lines (R05116). No new lines were derived for this study.

Statistical analysis

Mann–Whitney U-test and IBM SPSS Statistics software were used for determining statistical significance. Average (median) values of TER and pixel intensity obtained from cells cultured on each matrix were compared with average (median) values obtained on Col IV (reference) with Mann–Whitney U-test. p-Values≤0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

All protein coatings supported differentiation of hESC-RPE cells

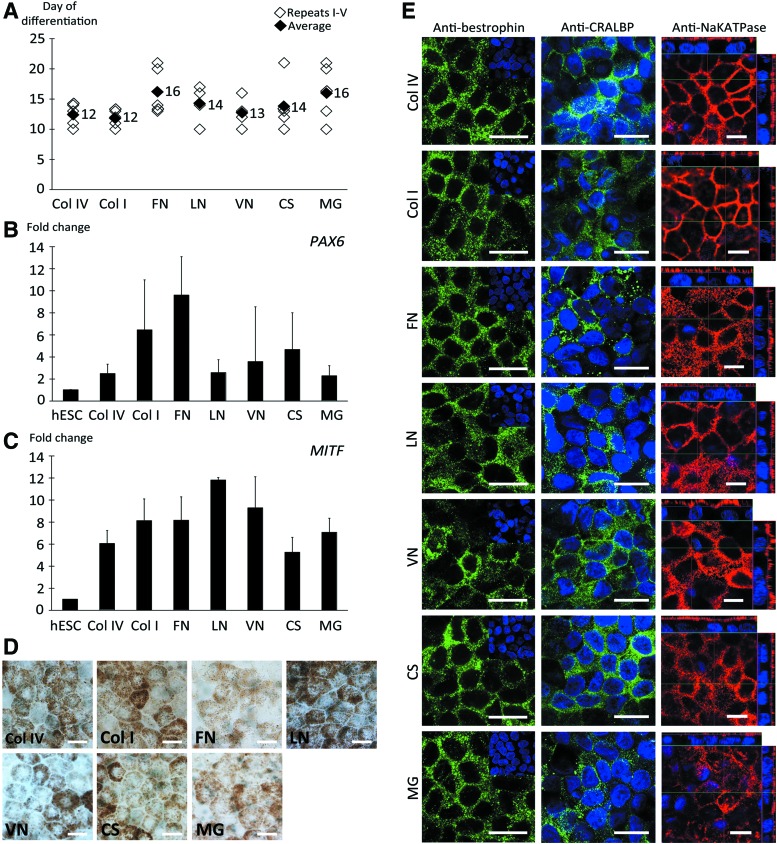

To study the effects of protein coatings on hESC-RPE differentiation and maturation, we differentiated hESCs to RPE cells as adherent cultures on five human-sourced ECM proteins and two commercially available hPSC culture substrata. All protein coatings allowed for competent differentiation of hESCs to RPE cells with no marked differences in the onset or degree of pigmentation at the early stage of differentiation process. The first pigmentation appeared within the interval of 10–21 days of differentiation (Fig. 1A). After 28 days of differentiation the cells showed increased gene expression of the early eye field marker PAX6 and RPE precursor marker MITF compared with undifferentiated hESCs. The MITF expression had increased from 5-fold on CS up to 10-fold on LN (Fig. 1B, C). The expression of MITF was significantly higher (p<0.005) on LN coating compared with the other tested coatings, except compared with VN (p=0.031). In contrast, the MITF expression on CS was significantly lower (p<0.005) compared with all other tested coatings, except Col IV (p=0.119). However, as overall the fold change differences were subtle (over twofold changes are considered biologically relevant) and our aim was to show the common trend of increased gene expression of early eye field and RPE precursor markers, we did not consider these differences biologically relevant. On day 28, an average of 0.9–1.7 pigmented cell clusters/cm2 (n=9–11 replicates) were gained on different coatings.

FIG. 1.

Characterization of early stage differentiation and maturation of human embryonic stem cell–derived retinal pigment epithelial (hESC-RPE) cells. RPE differentiation and maturation was achieved on all extracellular matrix (ECM) coatings tested. (A) Appearance of pigmentation in each differentiation experiment (n=5). Relative quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis of genes involved in retinal development, (B) paired box gene 6 (PAX6) and (C) microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), after 28 days of differentiation (n=4 experiments). (D) Bright-field images showing mature hESC-RPE with typical pigmented, cobblestone-like RPE morphology and (E) immunofluorescence (IF) staining showing correct expression and localization of RPE-specific proteins bestrophin (BEST) and cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein (CRALBP) after 140 days of differentiation. Vertical confocal sections show apical localization of Na+/K+ATPase confirming correct polarization of the epithelial monolayers on all coatings. Scale bars=10 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Sufficient pigmentation for replating was typically reached after 45 days of differentiation and the cells were efficiently enriched to monolayers of pigmented cells on all coatings by 98 days of differentiation. The hESC-RPE cells were further maturated on coated culture inserts up to 140 days of differentiation. Confluent, intact cell layers were produced on all substrates, but on LN and VN more fragile and ruptured epithelia were occasionally observed. All investigated coatings supported the maintenance of hexagonal and cobblestone-like RPE cell morphology (Fig. 1D). Human ESC-RPE cells were positive for mature RPE-related proteins BEST and CRALBP on all coatings and expressed Na+/K+ATPase on the apical membrane of the cells, demonstrating polarization of the formed epithelia (Fig. 1E). There was no expression of pluripotency markers OCT3/4 and Nanog on any of the studied protein coatings after 140 days of differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea). Further, no significant differences were found in gene expression analysis of mature RPE markers BEST, CRALBP, MERTK, and RPE65 after 140 days of differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S2). The functionality of hESC-RPE on Col IV, FN, LN, CS, and MG coatings was studied with phagocytosis of POS from rat retinal explants after 184 days of differentiation. After 2 days of coculture with the rat retinal explant, rat opsin was internalized inside hESC-RPE cells on all studied five coatings (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Protein coating affects the degree of pigmentation of hESC-RPE cells

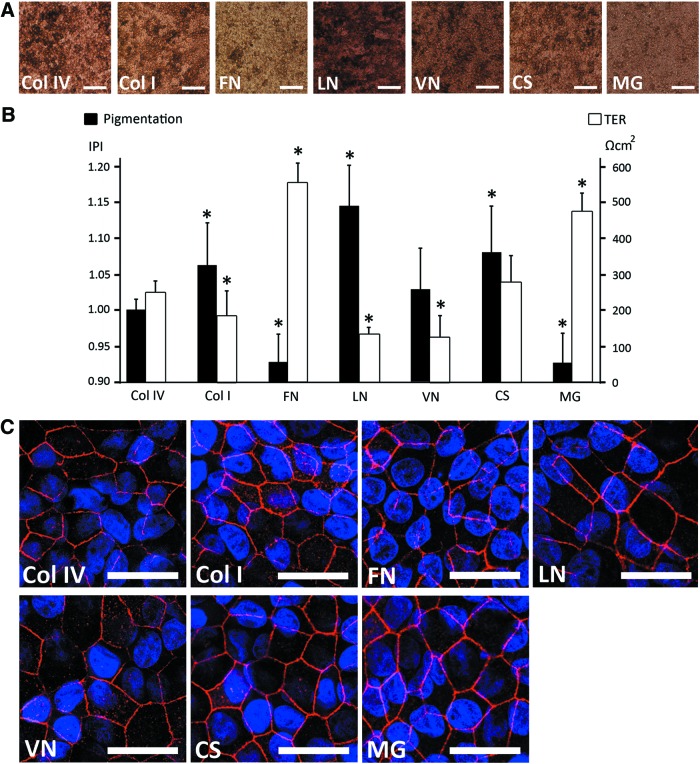

The used protein coating significantly affected the degree of pigmentation of the hESC-RPE layers in long-term differentiation. The differences in the densities of pigmentation were evident by visual microscopic inspection and the relative degree of pigmentation was quantified by calculating pixel intensities from phase-contrast images after 140 days of differentiation. On LN the hESC-RPE evinced the highest degree of pigmentation, whereas culture on FN and MG resulted in lower production of pigmentation. On Col IV, hESC-RPE showed intermediate pigmentation (Fig. 2A). The degree of pigmentation on VN varied substantially between the individual differentiation experiments. The relative degree of cell pigmentation was significantly (p<0.05) higher on LN, CS, and Col I, while on FN and MG the pigmentation was significantly lower as compared with Col IV (p<0.05) (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Degree of pigmentation and barrier properties of maturate hESC-RPE after 140 days of differentiation. (A) Phase-contrast images illustrating the degree of pigmentation on different coatings. Scale bars=100 μm. (B) Relative degree of pigmentation quantified by image analysis and presented as inverse of pixel intensity (IPI) (n=4), and transepithelial resistance (TER) measured for human pluripotent stem cell (hPSC)–RPE on different coatings (n=5). *p<0.05 compared with collagen IV (Col IV). (C) IF staining of tight junction protein zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1). Scale bars=10 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Barrier properties of the forming epithelium are strongly influenced by the protein coating

Development of the barrier properties and integrity of the RPE epithelia on different coatings were examined with TER measurements from cell culture inserts after 140 days of differentiation. We found major differences in TER values between investigated substrates (Fig. 2B). The highest TER values of 552±56 Ω·cm2 and 473±53 Ω·cm2 were measured for FN and MG, respectively. TER values reached 275±77 Ω·cm2 for CS, 247±35 Ω·cm2 for Col IV, and 183±72 Ω·cm2 for Col I. The lowest TER values were obtained for LN (128±25 Ω·cm2) and VN (122±64 Ω·cm2). The average TER value for the epithelium on all coatings, except that for CS, significantly (p<0.05) differed from the average TER for epithelium on Col IV (Fig. 2B).

We next studied the presence of tight junctions on the epithelia formed. Positivity of ZO-1 label in IF (Fig. 2C) and the electron dense band on apical side of lateral membrane seen in TEM (Fig. 3) confirmed the presence of tight junctions on the apical side of the cells in all of the used coatings.

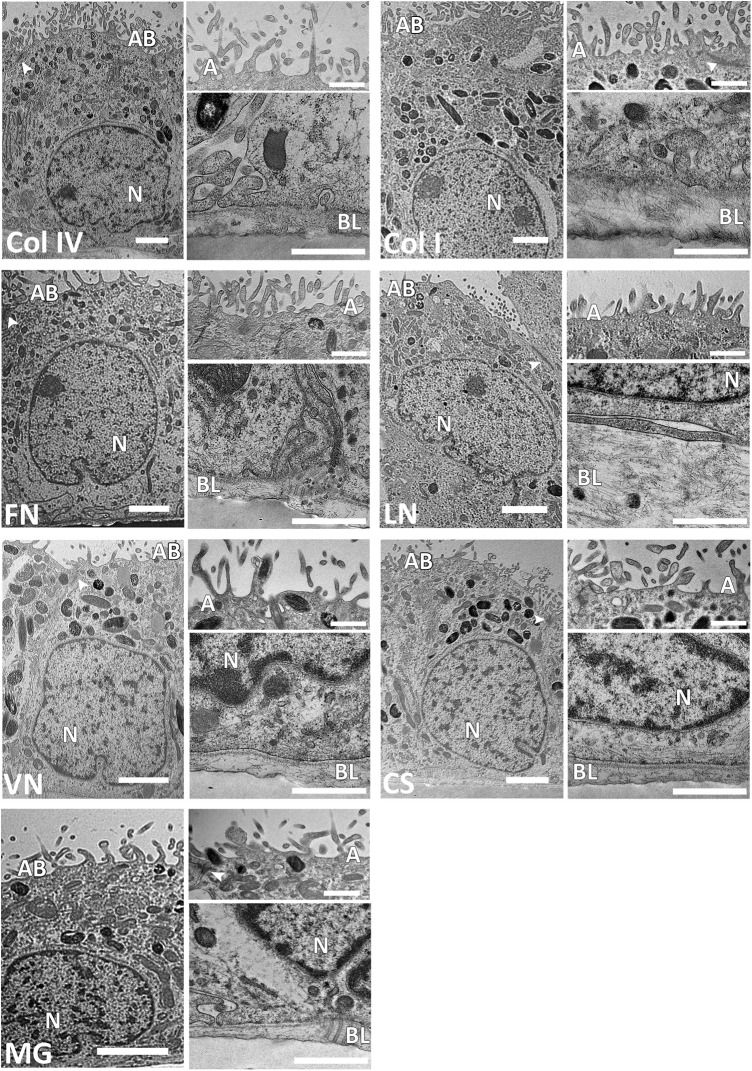

FIG. 3.

High-magnification transmission electron microscope (TEM) images showing the fine structure of maturated hESC-RPE on different coatings (scale bars=2 μm). Apical microvilli (A) and basal lamina (BL) shown in higher magnifications (scale bars=1 μm). TEM analysis confirmed the presence of tight junctions (arrowheads) on the apical side of the cells in all of the coatings. AB, apical brush border; N, nucleus.

Protein coating affects the fine structure of the hESC-RPE cells

The fine structure of hESC-RPE cells on different coatings was investigated with TEM. All coatings promoted the growth of the forming epithelium as a monolayer (Supplementary Fig. S4). We discovered variation in structure and thickness of hESC-RPE cells between coatings; cells on human Col I, Col IV, CS, FN, LN, and VN had columnar morphology, whereas hESC-RPE cells on MG showed a more cuboidal structure (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S4). The hESC-RPE cells had the greatest average cell thickness on LN (14.7±1.3 μm), whereas on Col I and Col IV, the average cell thicknesses reached for 13.8±0.1 μm and 13.2±2.4 μm, respectively. Moreover, cell thickness of 12.5±1.1 μm for FN, 10.9±0.5 μm for CS, and 10.8±1.4 μm for VN was found. The hESC-RPE cells were substantially thinner on MG with average cell thickness of 7.6±0.4 μm.

The nuclei of the cells were located basally on all tested coatings, whereas mitochondria and melanosomes were found mainly from the apical side of the cells. Fewer melanosomes were seen in hESC-RPE cells on FN and MG compared with the other coatings. The hESC-RPE cells cultured on FN and MG had rather straight apical borderline whereas hESC-RPE cells cultured on Col IV, Col I, LN, VN, and CS had roundish apical borderline. The apical microvilli of the cells were detected on all coatings, but the structure and density of microvilli differed between tested coatings (Fig. 3). The density of microvilli on VN, LN, and CS was low compared with Col IV, Col I, and FN. Moreover, the apical microvilli were shorter on LN and MG compared with the longer extensions seen on other tested coatings. Tight junctions were visualized at the apical side of the monolayers on all tested coatings. Further, coated pits were associated with both basal and apical membranes of hESC-RPE on all tested coatings.

The hESC-RPE cells assemble their own basal lamina

The ability of the hESC-RPE cells to produce and secrete the key ECM proteins of the basement membrane of the native RPE was investigated with qPCR analysis, IF staining, TEM, and western blotting. qPCR analysis of genes encoding for ECM proteins revealed no clear differences between protein coatings after 140 days of differentiation (Supplementary Fig. S5). However, the gene expression data confirmed that the genes encoding for the key ECM proteins of the basement membrane of the native RPE were transcripted. IF staining showed abundant labeling with Col IV, FN, and LN fibers on Col IV, Col I, LN, VN, and MG (Fig. 4). On FN and CS, cells produced low amounts of Col IV and LN, whereas FN fibers were not detected at all. IF staining confirmed the fiber-like conformation of all secreted basal lamina components and basal localization of Col IV and FN. LN was mostly localized basally, but some fibers were also detected at intercellular spaces. Negative IF control staining of empty inserts and Col IV-, FN-, and LN-coated inserts without cells had dotted-like staining (Supplementary Fig. S6), whereas ECM stainings with cells were in fiber-like form. This confirmed that the fiber-like ECM proteins seen in Figure 4 are being secreted by the cells.

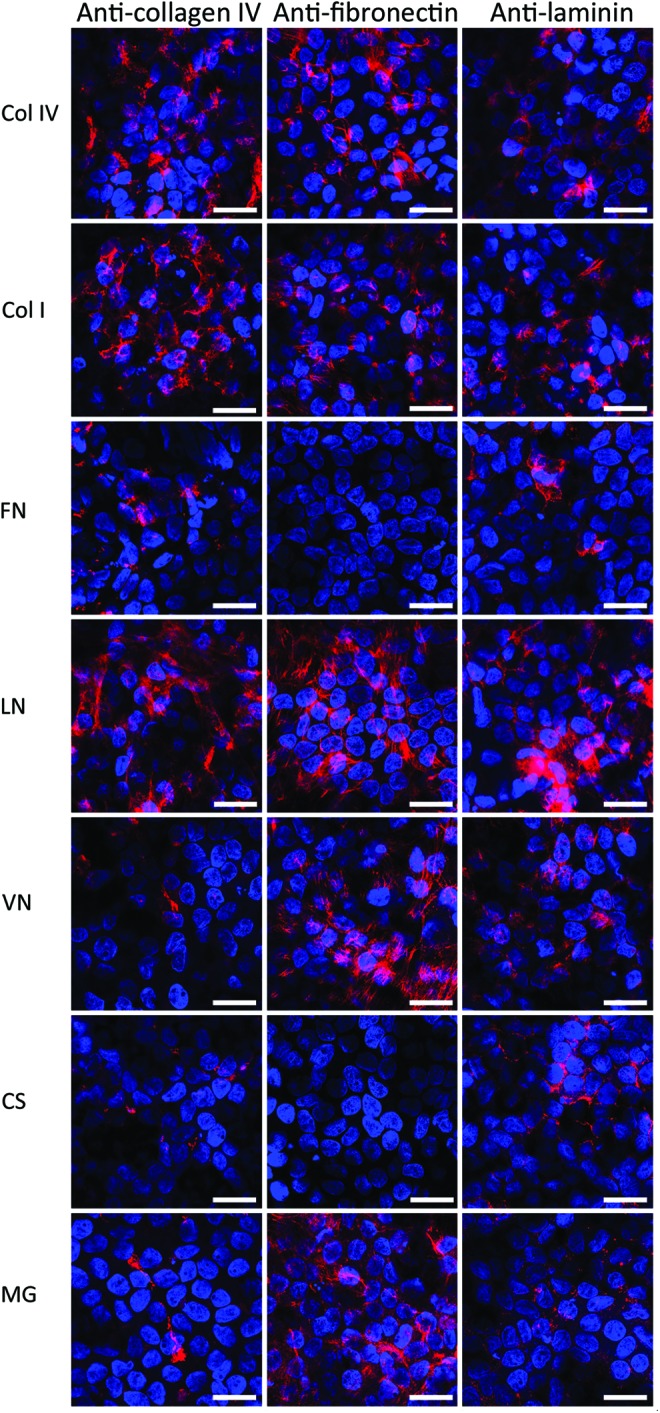

FIG. 4.

ECM protein production of maturated hESC-RPE on coatings. Col IV (first column), fibronectin (FN; second column), and laminin (LN; third column) production analyzed by IF stainings on different coatings after 140 days of differentiation. The nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylidole (DAPI). Scale bars=10 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

TEM analyses confirmed that the hESC-RPE cells assemble their own basal lamina. Substantial differences in the thickness of the self-assembled basal lamina on the different coatings were found. The hESC-RPE cells assembled the thickest basal lamina on LN (0.82±0.28 μm) and Col I (0.70±0.07 μm), whereas the thinnest basal lamina was seen on CS (0.22±0.05 μm) (Fig. 3). Moreover, the self-assembled basal lamina thickness was 0.31±0.08 μm for Col IV, 0.27±0.08 μm for FN, 0.33±0.06 μm for MG, and 0.32±0.06 μm for VN.

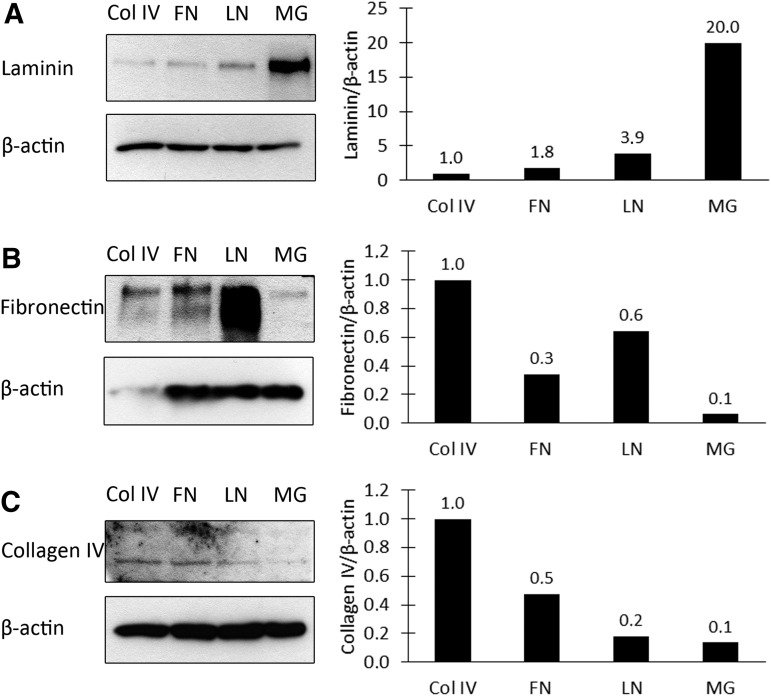

The effect of protein coating to the ECM production of hESC-RPE on Col IV, FN, LN, and MG coatings was quantified with western blotting (Fig. 5). Highest LN deposition was found on MG, whereas highest FN and Col IV deposition was detected on Col IV. Western blotting also confirmed FN to be deposited on FN coating in contrast to IF staining.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of the ECM protein production of maturated hESC-RPE on Col IV, FN, LN, and MG coatings. (A) LN production, (B) FN production, and (C) Col IV production after 140 days of differentiation.

Discussion

Efficient production of intact, mature, and functional sheets of hPSC-RPE cells is considered to be essential for their clinical applications.17 Most of the current hPSC-RPE differentiation protocols utilize xeno-derived substrates like porcine gelatin, even in the clinical setting.4 In this study, we compared the effect of xeno-free, human-sourced ECM protein coatings on the differentiation and maturation of hESC-RPE cells with the aim of finding suitable substrate for GMP-quality hESC-RPE production for clinical purposes. To our knowledge, the effects of different ECM proteins on maturation of hESC-RPE epithelium have not been previously studied although it is well acknowledged that primary RPE cells are influenced by their ECM and abnormal ECM can result in altered structure and functions, and engage in disease states.24–27

In the present study, we hypothesized that Col IV and LN, abundant components of the native RPE basement membrane, would be superior in supporting the hESC-RPE differentiation. Unexpectedly, all of the investigated protein coatings enabled differentiation of hESC-RPE monolayers in serum-free medium, and no relevant differences in the onset or rate of pigmentation, nor gene expression levels of PAX6 and MITF were found between coatings after 28 days of differentiation. Moreover, after 140 days of culture, the hESC-RPE displayed RPE-specific cobblestone morphology, expression of genes, and correct localization of RPE-specific proteins as well as phagocytic activity, indicating that all used protein coatings support the maturation of hESC toward RPE cell type. However, striking differences were found with structure and epithelial barrier properties, and these were further analyzed.

For RPE, the pigmentation is considered to be an important indicator of phenotypic maturity.49 In our study, we did not see any notable differences in the amount of pigmented areas after 4 weeks of differentiation between investigated protein coatings. In a study that tested several human- and animal-derived ECM proteins for hiPSC-RPE differentiation, Rowland et al. found significant differences in pigmentation density after 5 weeks of initial differentiation but no comparative analyses regarding further maturation with the different ECM proteins were conducted.41 In their study, mouse LN-111 and Matrigel induced highest degree of pigmentation. Thus, this mouse LN-111 was presented as a suitable matrix for hPSC-RPE differentiation, although monolayers of hiPSC-RPE with correct morphology and similar levels of RPE gene expression were achieved on most ECM protein coatings tested.41 This is in accordance with our results. Based on our results, it is clear that the early stage hESC-RPE differentiation is not significantly affected by the culture coating when spontaneous differentiation protocol omitting bFGF was used. However, when the long-term effect of culture coating on the degree of pigmentation (140 days of differentiation) was studied, we found significant differences in the degree of pigmentation between tested coatings. The hESC-RPE cells gained heavily pigmented cells on LN, whereas FN and MG consistently showed lower degree of pigmentation and correspondingly fewer melanosomes detected with TEM analysis.

It is known that ECM influences the polarity of many epithelia50 and the polarity of the RPE is maintained by the ECM on both the apical and basal sides of the RPE monolayer.51 In the present study, we saw that all matrices induced formation of polarized monolayer of hESC-RPE cells. There were no marked differences in the polarity of the epithelium on different matrices demonstrated by apical localization of Na+/K+ATPase. Moreover, tight junctions were detected on the apical side of the cells on all coatings both in confocal microscopy and TEM. Previously it has been reported that epithelial polarity is linked to formation of tight junctions and consequently to the barrier function of the tissue.52–54 Rizzolo has reported that individual matrix components influence the distribution of a subset of plasma membrane proteins required for full polarity in the RPE of chicken embryos and that the development of RPE polarity is a gradual process.55

Subtle differences in the cell shape or subcellular organization are suggested to have profound consequences for the efficient function of the RPE, and especially for the ability of the RPE to support the survival of photoreceptors.49 Here, the hESC-RPE cells on all coatings showed high degree of polarity with basally located nuclei with slightly folded nuclear membrane and apical melanosomes, apical tight junctions, coated pits, and high number of mitochondria, consistent with the previous publications that show hESC-RPE ultrastructure.12,44,46,56 However, the fine structure of hESC-RPE has been previously shown merely on Matrigel44,46 and on FN.56 It is noteworthy that in our study, TEM analysis revealed important differences in hESC-RPE ultrastructure between tested coatings; cells on Col IV, Col I, and FN matrices had denser and more homogenous microvilli and the overall thickness of cells was lower than of cells cultured on VN, LN, and CS, which can also reflect the degree of cellular maturation. Despite the lack of exposure the retina or POS,44,46 the TEM analysis revealed many features of hESC-RPE fine structure associated with proper epithelial maturity gained in vitro.

The sufficient ECM production by the hPSC-RPE is important regarding their clinical applications in regenerative medicine to ensure proper cell attachment, survival, and integration of the grafted cells onto damaged BM and possibly also remodeling it in AMD patients.57 In the present study, we show with TEM, qPCR, IF, and western blotting that the hESC-RPE produce and assemble their own basal lamina on all investigated coatings. Interestingly, marked differences in the thickness of the basal lamina were detected in TEM analysis. Surprisingly, the thickest basal lamina was detected on LN even though more fragile and ruptured epithelia were occasionally observed on LN and VN coatings. This might be due to poor coating success with these matrices. IF staining suggested the secretion of Col IV and LN on all matrices while on FN and CS we did not detect any production of FN. In western blotting, highest LN deposition was found on MG and LN, whereas FN and collagen deposition was most abundant on Col IV. On the contrary to IF stainings, western blotting confirmed FN to be deposited on FN coating. The reason for this discrepancy is not known, but it is repeatable result. Thickness of the native RPE basement membrane has been reported to be 0.14–0.15 μm.23 In our study, all investigated protein coatings induced the production of self-assembled ECM with thickness ranging from 0.22 to 0.82 μm. This and the highly organized structure seen in TEM and IF suggests that these studied protein coatings allow proper cues for hESC-RPE to form functional basement membrane. To our knowledge, the assembly of hESC-RPE basal lamina and these key ECM components has previously been shown only for cells cultured on growth factor (e.g., TGFβ)–containing Matrigel44,46 although it is well acknowledged that native RPE cells secrete the key components of BM.58–60 To our awareness, the present study is the first to demonstrate that the expression of these secretary ECM proteins in hESC-RPE is clearly influenced by the protein coating.

In vitro, the cobblestone-like RPE cell morphology, expression of RPE-specific proteins, appropriate subcellular localization of polarized proteins, and pigmentation and barrier properties of RPE cells are generally considered to be hallmarks of mature RPE.49,61 It is vitally important to have valid criteria to define maturity of RPE cells for the stem-cell-based transplantation therapies. RPE cells with high degree of pigmentation are considered to be a golden standard for selection of cells for clinical applications,4,17 whereas in the experimental series the high TER has been the inclusion criteria.56,62 Melanin pigment in RPE cells decreases detrimental effects of Fenton reaction and diminish cytotoxic lipid peroxidation, lipofuscin accumulation, and subsequently chronic inflammation involved in AMD pathology.63–65 In addition, phagocytosis of retinal outer segment promotes tyrosinase biosynthesis, and RPE cell pigmentation is an indication of the cell maturity and functionality.66 In a recent report, Schwartz et al. reported greater attachment and spreading of the hESC-RPE with lower degree of pigmentation compared with darkly pigmented cells after culture. This data suggests that the extent of hESC-RPE maturity and pigmentation in vitro might substantially affect the attachment of transplanted cells to BM and their subsequent survival and integration to the host RPE layer.4 Interestingly in our study, the pigmentation of the epithelium showed an inverse correlation to the epithelial resistance; the heavily pigmented epithelia on LN showed lowest TER values whereas FN and MG resulted in lower production of pigmentation and highest TER values. Even though TER and the degree of pigmentation are not conceptually related, we found the inverse relationship of this hallmarks of maturation unexpected phenomenon. This inverse relationship for hESC-RPE pigmentation and epithelial barrier integrity (TER) has not been described previously and this aspect of the epithelium maturation warrants further investigations in respect of functionality of transplanted cells in vivo.

In the beginning we hypothesized that Col IV and LN, both ECM components that reside in the closest proximity of RPE cells in their natural environment, would be superior in inducing differentiation and maturation of hESC-RPE cells. Col IV induced formation of polarized monolayer of cells with the average height of cells, low to average thickness of basal lamina, and average barrier function. LN also induced formation of polarized monolayer of cells with tallest cells, thickest basal lamina, and highest degree of pigmentation but the lowest barrier function. Therefore, we can summarize that Col IV is in the golden midway in all the assessed criteria. LN was superior in all other studied aspects except the barrier function. Still the importance of that factor needs to be elucidated.

Conclusion

In this study, we investigated the effect of seven different protein coatings on differentiation and maturation of hESC-RPE cells. We found single protein substrate to have a crucial effect on the maturation of the RPE epithelium, its pigmentation, barrier properties, and assembly of basal lamina. We produced functional hESC-RPE cells with several xeno-free human-sourced matrices suitable for GMP-quality hESC-RPE production for clinical purposes. This article is the first to report that cell culture coating has a major structural and functional effect on the maturation of hESC-RPE potentially affecting cell integrations and survival after cell transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank TEKES, the Finnish Funding Agency for Technology and Innovation, the Academy of Finland (grant numbers 218050 and 137801), and Tampere Graduate Program in Biomedicine and Biotechnology for financial support. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis; decision to publish; or preparation of the article. Outi Melin, Hanna Koskenaho, Elina Konsén, Outi Heikkilä, Raija Hukkila, Soile Nymark, and Johanna Viiri are thanked for technical assistance.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Simo R., Villarroel M., Corraliza L., Hernandez C., and Garcia-Ramirez M.The retinal pigment epithelium: something more than a constituent of the blood-retinal barrier—implications for the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010,190724, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gehrs K.M., Anderson D.H., Johnson L.V., and Hageman G.S.Age-related macular degeneration—emerging pathogenetic and therapeutic concepts. Ann Med 38,450, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ambati J., and Fowler B.J.Mechanisms of age-related macular degeneration. Neuron 75,26, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz S.D., Hubschman J.P., Heilwell G., Franco-Cardenas V., Pan C.K., Ostrick R.M., Mickunas E., Gay R., Klimanskaya I., and Lanza R.Embryonic stem cell trials for macular degeneration: a preliminary report. Lancet 379,713, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vazin T., and Freed W.J.Human embryonic stem cells: derivation, culture, and differentiation: a review. Restor Neurol Neurosci 28,589, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klimanskaya I., Hipp J., Rezai K.A., West M., Atala A., and Lanza R.Derivation and comparative assessment of retinal pigment epithelium from human embryonic stem cells using transcriptomics. Cloning Stem Cells 6,217, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Idelson M., Alper R., Obolensky A., Ben-Shushan E., Hemo I., Yachimovich-Cohen N., Khaner H., Smith Y., Wiser O., Gropp M., Cohen M.A., Even-Ram S., Berman-Zaken Y., Matzrafi L., Rechavi G., Banin E., and Reubinoff B.Directed differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into functional retinal pigment epithelium cells. Cell Stem Cell 5,396, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirami Y., Osakada F., Takahashi K., Okita K., Yamanaka S., Ikeda H., Yoshimura N., and Takahashi M.Generation of retinal cells from mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Neurosci Lett 458,126, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchholz D.E., Hikita S.T., Rowland T.J., Friedrich A.M., Hinman C.R., Johnson L.V., and Clegg D.O.Derivation of functional retinal pigmented epithelium from induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 27,2427, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vaajasaari H., Ilmarinen T., Juuti-Uusitalo K., Rajala K., Onnela N., Narkilahti S., Suuronen R., Hyttinen J., Uusitalo H., and Skottman H.Toward the defined and xeno-free differentiation of functional human pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelial cells. Mol Vis 17,558, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu B., Malcuit C., Wang S., Girman S., Francis P., Lemieux L., Lanza R., and Lund R.Long-term safety and function of RPE from human embryonic stem cells in preclinical models of macular degeneration. Stem Cells 27,2126, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr A.J., Vugler A.A., Hikita S.T., Lawrence J.M., Gias C., Chen L.L., Buchholz D.E., Ahmado A., Semo M., Smart M.J., Hasan S., da Cruz L., Johnson L.V., Clegg D.O., and Coffey P.J.Protective effects of human iPS-derived retinal pigment epithelium cell transplantation in the retinal dystrophic rat. PLoS One 4,e8152, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li Y., Tsai Y.T., Hsu C.W., Erol D., Yang J., Wu W.H., Davis R.J., Egli D., and Tsang S.H.Long-term safety and efficacy of human induced pluripotent stem cell (iPS) grafts in a preclinical model of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Med 18,1312, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thumann G., Viethen A., Gaebler A., Walter P., Kaempf S., Johnen S., and Salz A.K.The in vitro and in vivo behaviour of retinal pigment epithelial cells cultured on ultrathin collagen membranes. Biomaterials 30,287, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu B., Zhu D., Hinton D., Humayun M.S., and Tai Y.C.Mesh-supported submicron parylene-C membranes for culturing retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biomed Microdevices 14,659, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subrizi A., Hiidenmaa H., Ilmarinen T., Nymark S., Dubruel P., Uusitalo H., Yliperttula M., Urtti A., and Skottman H.Generation of hESC-derived retinal pigment epithelium on biopolymer coated polyimide membranes. Biomaterials 33,8047, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Y., Liu L., Lu B., Zhu D., Ribeiro R., Diniz B., Thomas P.B., Ahuja A.K., Hinton D.R., Tai Y.C., Hikita S.T., Johnson L.V., Clegg D.O., Thomas B.B., and Humayun M.S.A novel approach for subretinal implantation of ultrathin substrates containing stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium monolayer. Ophthalmic Res 48,186, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarbin M.A.Analysis of retinal pigment epithelium integrin expression and adhesion to aged submacular human Bruch's membrane. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc 101,499, 2003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Labat-Robert J.Cell-Matrix interactions, the role of fibronectin and integrins. A survey. Pathol Biol (Paris) 60,15, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hynes R.O.The extracellular matrix: not just pretty fibrils. Science 326,1216, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prowse A.B., Chong F., Gray P.P., and Munro T.P.Stem cell integrins: implications for ex-vivo culture and cellular therapies. Stem Cell Res 6,1, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim D.H., Provenzano P.P., Smith C.L., and Levchenko A.Matrix nanotopography as a regulator of cell function. J Cell Biol 197,351, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Booij J.C., Baas D.C., Beisekeeva J., Gorgels T.G., and Bergen A.A.The dynamic nature of Bruch's membrane. Prog Retin Eye Res 29,1, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho T.C., and Del Priore L.V.Reattachment of cultured human retinal pigment epithelium to extracellular matrix and human Bruch's membrane. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 38,1110, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tezel T.H., and Del Priore L.V.Serum-free media for culturing and serial-passaging of adult human retinal pigment epithelium. Exp Eye Res 66,807, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mousa S.A., Lorelli W., and Campochiaro P.A.Role of hypoxia and extracellular matrix-integrin binding in the modulation of angiogenic growth factors secretion by retinal pigmented epithelial cells. J Cell Biochem 74,135, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith-Thomas L., Richardson P., Parsons M.A., Rennie I.G., Benson M., and MacNeil S.Additive effects of extra cellular matrix proteins and platelet derived mitogens on human retinal pigment epithelial cell proliferation and contraction. Curr Eye Res 15,739, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hiscott P., Sheridan C., Magee R.M., and Grierson I.Matrix and the retinal pigment epithelium in proliferative retinal disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 18,167, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hageman G.S., Mullins R.F., Russell S.R., Johnson L.V., and Anderson D.H.Vitronectin is a constituent of ocular drusen and the vitronectin gene is expressed in human retinal pigmented epithelial cells. FASEB J 13,477, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hurt E.M., Chan K., Serrat M.A., Thomas S.B., Veenstra T.D., and Farrar W.L.Identification of vitronectin as an extrinsic inducer of cancer stem cell differentiation and tumor formation. Stem Cells 28,390, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donoso L.A., Kim D., Frost A., Callahan A., and Hageman G.The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol 51,137, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alcazar O., Cousins S.W., Striker G.E., and Marin-Castano M.E.(Pro)renin receptor is expressed in human retinal pigment epithelium and participates in extracellular matrix remodeling. Exp Eye Res 89,638, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newsome D.A., Huh W., and Green W.R.Bruch's membrane age-related changes vary by region. Curr Eye Res 6,1211, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hollyfield J.G., and Rayborn M.E.Hyaluronan localization in tissues of the mouse posterior eye wall: absence in the interphotoreceptor matrix. Exp Eye Res 65,603, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Termeer C., Benedix F., Sleeman J., Fieber C., Voith U., Ahrens T., Miyake K., Freudenberg M., Galanos C., and Simon J.C.Oligosaccharides of Hyaluronan activate dendritic cells via toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med 195,99, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hageman G.S., Luthert P.J., Victor Chong N.H., Johnson L.V., Anderson D.H., and Mullins R.F.An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch's membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res 20,705, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crabb J.W., Miyagi M., Gu X., Shadrach K., West K.A., Sakaguchi H., Kamei M., Hasan A., Yan L., Rayborn M.E., Salomon R.G., and Hollyfield J.G.Drusen proteome analysis: an approach to the etiology of age-related macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99,14682, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ma W., Tavakoli T., Derby E., Serebryakova Y., Rao M.S., and Mattson M.P.Cell-extracellular matrix interactions regulate neural differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. BMC Dev Biol 8,90, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gong J., Sagiv O., Cai H., Tsang S.H., and Del Priore L.V.Effects of extracellular matrix and neighboring cells on induction of human embryonic stem cells into retinal or retinal pigment epithelial progenitors. Exp Eye Res 86,957, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boucherie C., Mukherjee S., Henckaerts E., Thrasher A.J., Sowden J.C., and Ali R.R.Self-organising neuroepithelium from human pluripotent stem cells facilitates derivation of photoreceptors. Stem Cells 31,408, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowland T.J., Blaschke A.J., Buchholz D.E., Hikita S.T., Johnson L.V., and Clegg D.O.Differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells to retinal pigmented epithelium in defined conditions using purified extracellular matrix proteins. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 7,642, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rowland T.J., Buchholz D.E., and Clegg D.O.Pluripotent human stem cells for the treatment of retinal disease. J Cell Physiol 227,457, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buchholz D.E., Pennington B.O., Croze R.H., Hinman C.R., Coffey P.J., and Clegg D.O.Rapid and efficient directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into retinal pigmented epithelium. Stem Cells Transl Med 2,384, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vugler A., Carr A.J., Lawrence J., Chen L.L., Burrell K., Wright A., Lundh P., Semo M., Ahmado A., Gias C., da Cruz L., Moore H., Andrews P., Walsh J., and Coffey P.Elucidating the phenomenon of HESC-derived RPE: anatomy of cell genesis, expansion and retinal transplantation. Exp Neurol 214,347, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Skottman H.Derivation and characterization of three new human embryonic stem cell lines in Finland. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 46,206, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carr A.J., Vugler A., Lawrence J., Chen L.L., Ahmado A., Chen F.K., Semo M., Gias C., da Cruz L., Moore H.D., Walsh J., and Coffey P.J.Molecular characterization and functional analysis of phagocytosis by human embryonic stem cell-derived RPE cells using a novel human retinal assay. Mol Vis 15,283, 2009 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zahabi A., Shahbazi E., Ahmadieh H., Hassani S.N., Totonchi M., Taei A., Masoudi N., Ebrahimi M., Aghdami N., Seifinejad A., Mehrnejad F., Daftarian N., Salekdeh G.H., and Baharvand H.A new efficient protocol for directed differentiation of retinal pigmented epithelial cells from normal and retinal disease induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 21,2262, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Livak K.J., and Schmittgen T.D.Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25,402, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burke J.M.Epithelial phenotype and the RPE: is the answer blowing in the Wnt? Prog Retin Eye Res 27,579, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoker A.W., Streuli C.H., Martins-Green M., and Bissell M.J.Designer microenvironments for the analysis of cell and tissue function. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2,864, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Crawford B.J.Some factors controlling cell polarity in chick retinal pigment epithelial cells in clonal culture. Tissue Cell 15,993, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gonzalez-Mariscal L., Betanzos A., Nava P., and Jaramillo B.E.Tight junction proteins. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 81,1, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jensen A.M., and Westerfield M.Zebrafish mosaic eyes is a novel FERM protein required for retinal lamination and retinal pigmented epithelial tight junction formation. Curr Biol 14,711, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schneeberger E.E., and Lynch R.D.The tight junction: a multifunctional complex. American journal of physiology. Cell Physiol 286,C1213, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rizzolo L.J.Basement membrane stimulates the polarized distribution of integrins but not the Na, K-ATPase in the retinal pigment epithelium. Cell Regul 2,939, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu D., Deng X., Spee C., Sonoda S., Hsieh C.L., Barron E., Pera M., and Hinton D.R.Polarized secretion of PEDF from human embryonic stem cell-derived RPE promotes retinal progenitor cell survival. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52,1573, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sugino I.K., Gullapalli V.K., Sun Q., Wang J., Nunes C.F., Cheewatrakoolpong N., Johnson A.C., Degner B.C., Hua J., Liu T., Chen W., Li H., and Zarbin M.A.Cell-deposited matrix improves retinal pigment epithelium survival on aged submacular human Bruch's membrane. Invest Ophthal Vis Sci 52,1345, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campochiaro P.A., Jerdon J.A., and Glaser B.M.The extracellular matrix of human retinal pigment epithelial cells in vivo and its synthesis in vitro. Invest Ophthal Vis Sci 27,1615, 1986 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kamei M., Kawasaki A., and Tano Y.Analysis of extracellular matrix synthesis during wound healing of retinal pigment epithelial cells. Microsc Res Tech 42,311, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kigasawa K., Ishikawa H., Obazawa H., Minamoto T., Nagai Y., and Tanaka Y.Collagen production by cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Tokai J Exp Clin Med 23,147, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Binder S., Stanzel B.V., Krebs I., and Glittenberg C.Transplantation of the RPE in AMD. Prog Retin Eye Res 26,516, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Savolainen V., Juuti-Uusitalo K., Onnela N., Vaajasaari H., Narkilahti S., Suuronen R., Skottman H., and Hyttinen J.Impedance spectroscopy in monitoring the maturation of stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium. Ann Biomed Eng 39,3055, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burke J.M., Kaczara P., Skumatz C.M., Zareba M., Raciti M.W., and Sarna T.Dynamic analyses reveal cytoprotection by RPE melanosomes against non-photic stress. Mol Vis 17,2864, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kaczara P., Zareba M., Herrnreiter A., Skumatz C.M., Zadlo A., Sarna T., and Burke J.M.Melanosome-iron interactions within retinal pigment epithelium-derived cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res 25,804, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peters S., and Schraermeyer U.Characteristics and functions of melanin in retinal pigment epithelium. Ophthalmologe 98,1181, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schraermeyer U., Kopitz J., Peters S., Henke-Fahle S., Blitgen-Heinecke P., Kokkinou D., Schwarz T., and Bartz-Schmidt K.U.Tyrosinase biosynthesis in adult mammalian retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res 83,315, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.