Abstract

Optimal use of antiretroviral drugs by pregnant women living with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is crucial to treat maternal HIV infection and prevent perinatal transmission of the virus effectively. Our goal was to describe national trends of antiretroviral (ARV) use during pregnancy among HIV-infected women living in the U.S. and enrolled in Medicaid. We used the 2000–2007 Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) files to identify our study cohort. ARV use was defined as the dispensing of at least one ARV drug prescription during pregnancy based on Medicaid pharmacy claims. The prevalence of HIV was calculated, and temporal trends of ARV use during pregnancy were compared to the U.S. perinatal treatment guidelines. Predictors of ARV use during pregnancy were assessed using logistic regression models. From 1,106,757 pregnancies (955,251 women), 3083 (2856 women, 0.28%) were identified as HIV positive. We found striking regional variations in the prevalence of HIV and ARV prescription dispensing among pregnant women. The states with the highest HIV prevalence were Washington DC (5.8%), Maryland (0.90%), and New York (0.89%); all other states had a prevalence below 0.5%. A substantial fraction of women did not have any ARV dispensing throughout pregnancy (637 of 3083 (21%) pregnancies), and women with limited health care utilization were the least likely to have ARV dispensings. This finding calls for further research to better characterize HIV-positive women who are enrolled in Medicaid prior to pregnancy and yet have no ARV prescriptions so that appropriate interventions can be implemented.

Introduction

Optimal management of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) during pregnancy represents an important public health priority, especially in light of the strong and bold global commitment for virtual elimination of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV by 2015.1 In the United States, while MTCT rates have been reduced to less than 2% for over a decade, still perinatal transmission of HIV continues to occur, often indicating a woman who had undiagnosed HIV infection before pregnancy or one who did not receive appropriate interventions to prevent transmission of the virus to her infant.2 The US perinatal guidelines for the use of antiretroviral (ARV) drugs during pregnancy among HIV-infected women have evolved considerably over the years since their first edition in 1998.3 The guidelines place emphasis on full access to ARV combination regimens to treat maternal HIV infection and prevent perinatal HIV transmission.4 Regimen selection is individualized based on several factors, which include medical experience with use of specific ARVs in pregnancy, patient adherence, co-morbidities, and potential teratogenic effects and other adverse effects on fetuses and newborns.4 Twenty-five alternative choices for individual ARV drugs are now available, most approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since the mid-1990s.5 This has resulted in a wide variation of ARV combination regimens, including several recommended first line regimes, accessible to the HIV population in general and to HIV-infected pregnant women.

Approximately 50% of people receiving medical care for HIV in the US are covered by Medicaid, a joint state and federal health insurance program for low-income Americans.6 Medicaid also covers medical care for over 40% of births in the nation,7 making it the single largest source of health care coverage for individuals who are both pregnant and living with HIV. Despite this central role of Medicaid for the care of HIV-infected pregnant women, there is a lack of comprehensive information regarding access to ARV medication for this population. For example, temporal trends in ARV use for Medicaid enrolled women have never been compared with the US national perinatal treatment guidelines, but this comparison would be instructive for both policy makers and health care professionals.

We used national data from the US Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) files to characterize trends of ARV use during pregnancy among HIV-infected women enrolled in Medicaid between 2000 and 2007.

Methods

Study source population

MAX consists of individual-level data files on Medicaid eligibility and health care service utilization. The service utilization data include inpatient, outpatient, and nonhospital pharmacy dispensing claims. MAX data is available through the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and includes state-level data files for 50 states and the District of Columbia.8 This project was approved by Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard School of Public Health Institutional Review Boards and data use agreements were in place.

A national pregnancy cohort for studies of drug utilization and safety has been created from MAX data.9 Briefly, the cohort was formed by identifying delivery-related encounters based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis and procedure codes and the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes. Women with delivery-related encounters from 2000 to 2007 were linked to infants by matching on state, Medicaid Case Number, and the date of delivery. Date of the last menstrual period (LMP) was estimated using a validated algorithm as 245 days before delivery for preterm births, and 270 days before delivery for all other pregnancies because neither LMP nor gestational age at birth are available in MAX.10 After applying rigorous eligibility criteria to ensure complete follow-up throughout pregnancy and complete ascertainment of pharmacy prescription dispensing, the pregnancy cohort consisted of 1,248,875 pregnancies from 1,072,352 women from 46 US states and the District of Columbia.

Study cohort

For this study, we restricted the cohort of pregnancies in MAX to women who had continuous enrollment in Medicaid from at least 3 months prior to the LMP through delivery. We classified women as HIV-infected if they met the following criteria any time between 365 days prior to the LMP and delivery: two or more HIV ICD-9 diagnosis codes (inpatient or outpatient: 042-044.9, V08, 795.71, 795.8, 079.53, 7958, or 79571) separated by at least 30 days; two or more dispensing of ARV drug prescriptions separated by at least 30 days; or a combination of one HIV diagnosis code, one ARV prescription dispensing and at least one laboratory testing code for CD4 count or viral load.

Definition of study covariates

We obtained information on age and race from Medicaid enrollment files. Information on date of first ICD-9 code indicative of HIV, co-morbidities (chronic and gestational hypertension, chronic and gestational diabetes, chronic renal disease, cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, neoplasm, coagulopathy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and obesity), HIV-related conditions (pneumocystis pneumonia, tuberculosis, Kaposi's sarcoma, cytomegalovirus infection, toxoplasmosis, HIV encephalopathy, cryptosporidiosis, isosporiasis, histoplamosis, coccidiomycosis, or lymphoma), depression, other mental health disorders, tobacco, alcohol and illegal drug abuse was abstracted from Medicaid inpatient and outpatient files, anytime from 90 days prior to the LMP through to delivery. As proxies for general health status and health care utilization, we also calculated the number of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and prescription of non-ARV drugs from 90 days before the LMP and during pregnancy.11

ARV use during pregnancy

We defined pregnancy periods as before pregnancy (90 days prior to LMP through one day prior to LMP); first trimester (LMP to 90 days gestation); second trimester (91–180 days gestation); and third trimester (181 days to delivery). Prescriptions for ARVs were identified from Medicaid pharmacy claims, and ARV use during pregnancy was defined as the dispensing of at least one ARV drug prescription during pregnancy. We classified use of ARVs individually, by drug class (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), protease inhibitor (PI), or other), and by combination regimen categories (1 NRTI, 2 NRTIs, ≥3 NRTIs, ≥2 NRTIs+NNRTI, ≥2 NRTIs+PI, ≥2 NRTIs+NNRTI+PI, or other regimen). For the purposes of this study, we defined combination regimens based on at least one dispensing for the ARV components of the specific regimen during pregnancy, and not necessarily ARV dispensing that occurred concurrently or supplies that overlapped.

HIV prevalence and trends of ARV use during pregnancy

We calculated the overall prevalence of HIV among pregnant women in MAX between 2000 and 2007 and calculated the prevalence for each state. The proportion of HIV-infected pregnant women who used ARVs were calculated for each calendar year (based on year of LMP) to evaluate temporal trends of ARV use.

Prediction model for no ARV use during pregnancy

We used univariable logistic regression models to identify characteristics associated with no ARV use during pregnancy. Variables with a two-sided p value<0.20 were included in the multivariable prediction model, and those with a p value>0.10 in the adjusted model were removed one at a time, starting with the variable that had the largest p value. We fit models with generalized estimating equations (GEE) to account for clustering of multiple pregnancies within the same woman. All calculations were performed using SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Study cohort and HIV prevalence

Of the 1,248,875 pregnancies in MAX between 2000 and 2007, 1,106,757 (955,251 women) were enrolled in Medicaid from 3 months prior to the LMP through delivery. From these pregnancies, we identified 3083 (0.28%) as HIV positive; most pregnancies (87%) had two or more diagnosis claims for HIV between 365 days prior to the LMP through delivery. Four states had no HIV-infected pregnant women based on our algorithm for identifying those infected: Alaska, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming. The states with the highest HIV prevalence were Maryland (0.90%), New York (0.89%), Florida (0.81%), Louisiana (0.65%), Georgia (0.58%), and Washington DC, which was an outlier with a prevalence of 5.8%. All other states had prevalence below 0.5% (see Appendix 1). The estimated rankings of HIV prevalence by state in our study cohort were similar to estimates from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), as shown in Appendix 2 (Spearman correlation coefficient of the ranked prevalence=0.87).

ARV use during pregnancy

A total of 2254 pregnant women (2446 pregnancies, 79%) had at least one ARV prescription dispensing at some point during pregnancy. The states with the highest ARV coverage among pregnant women living with HIV were Alabama (98%), Maryland (93%), Mississippi (91%), and Massachusetts (90%); those with the lowest use were Hawaii (57%), New Mexico (50%), New Jersey (30%), and Oregon (29%) (Appendix 3). No ARVs were used in 637 (21%) of the pregnancies. Compared to the women who used ARVs during pregnancy, those who did not were slightly younger, more likely to have their first ICD-9 code indicative of HIV during (rather than before) pregnancy, and less likely to have laboratory measures for CD4 count or viral load in the first trimester (Table 1). The proportion of women without any ARV prescription during pregnancy fluctuated between 13% and 25% over the study years (Fig. 1a).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 3083 HIV-Infected Pregnancies (2856 Women) Within the Medicaid Analytic eXtract Stratified by ARV Use During Pregnancy

| Dispensing of ARV drug prescription(s) during pregnancy | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic, n (%) | NO (N=637) | YES (N=2446) | p Valuea |

| Age in years | <0.001 | ||

| 13–24 | 270 (42) | 852 (35) | |

| 25–34 | 294 (46) | 1192 (49) | |

| >35 | 73 (11) | 402 (16) | |

| Race | <0.001 | ||

| Black | 400 (63) | 1736 (71) | |

| White | 99 (15) | 327 (13) | |

| Hispanic | 90 (14) | 287 (12) | |

| Other/unknown | 48 (8) | 96 (4) | |

| Diagnoses of co-morbiditiesb | 208 (33) | 897 (37) | 0.060 |

| Diagnosis of depression | 106 (17) | 452 (18) | 0.28 |

| Diagnosis of other mental health disorders | 84 (13) | 371 (15) | 0.21 |

| Date of first claim indicative of HIV infection | <0.001 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy | 174 (34) | 1314 (54) | |

| 1st trimester | 141 (27) | 470 (19) | |

| 2nd trimester | 112 (22) | 503 (21) | |

| 3rd trimester | 87 (17) | 159 (7) | |

| Prescription fills for ARVs before pregnancy | 131 (21) | 1073 (44) | <0.001 |

| Diagnosis of possibly HIV-related illnesses | 6 (1) | 34 (1) | 0.37 |

| Laboratory measure for CD4 or viral load in the first trimester | 85 (13) | 873 (36) | <0.0001 |

| Number of distinct prescription fills for non-ARV drugs, mean (range) | |||

| Pre-pregnancy | 2.0 (0–18) | 2.5 (0–30) | <0.001 |

| During pregnancy | 6.2 (0–45) | 9.0 (0–77) | <0.001 |

| Number of distinct outpatients visits for any reason, mean (range) | |||

| Pre-pregnancy | 1.4 (0–41) | 1.5 (0–73) | 0.84 |

| During pregnancy | 28.3 (0–259) | 33.1 (3–271) | <0.001 |

| Number of distinct hospitalizations for any reason, mean (range) | |||

| Pre-pregnancy | 0.1 (0–3) | 0.1 (0–4) | 0.47 |

| During pregnancy | 0.5 (0–6) | 0.6 (0–14) | 0.02 |

| Alcohol abuse | 23 (4) | 93 (4) | 0.82 |

| Drug abuse | 74 (12) | 302 (12) | 0.62 |

| Tobacco use | 34 (5) | 168 (7) | 0.16 |

ARV, antiretroviral; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Fishers exact test for binary variables, Pearson Chi square for categorical variables, and 2-sample t-test for continuous measures.

Chronic hypertension, transient hypertension of pregnancy (gestational hypertension), pre-gestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, chronic renal disease, cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, neoplasm, thrombophilia, obesity, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, tobacco use, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, depression, and mental health disorders.

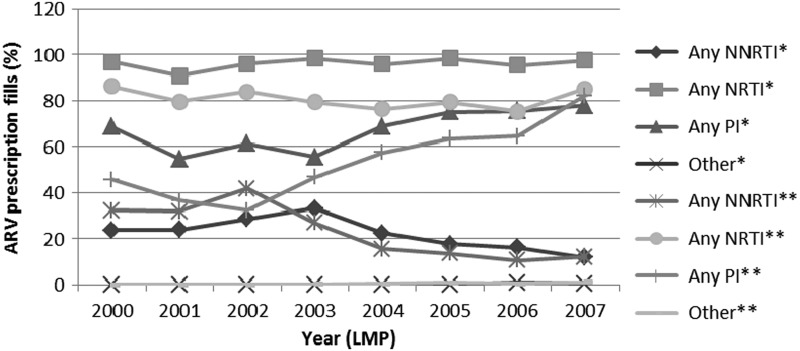

FIG. 1.

Temporal trends in dispensing of antiretroviral (ARV) drug prescriptions by drug class and for individual ARVs (in mono or combination drugs) among 3083 HIV-infected pregnancies (2856 women) within the Medicaid Analytic eXtract. ARV, antiretroviral; LMP, last menstrual period; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor. Note: Percentages are>100% in each period due to use of combination ARV regimes.

ARV use during pregnancy in Medicaid compared to the US Perinatal Guidelines

Among women who used ARVs, prescription patterns for ARVs during pregnancy were concordant with the US perinatal guidelines over time (Fig. 1a). The most common drug class used was NRTIs, mainly lamivudine (3TC) plus zidovudine (ZDV), which are the dual-NRTI regimen backbone recommended for pregnant women (Fig. 1b). PIs were the second most commonly used ARVs; nelfinavir (NFV) was the most used PI until 2005. By 2006, use of NFV and ritonavir-booted lopinavir (LPV/r) were almost equal, following the updated guidelines of 2006 that recommended both agents for use in pregnancy.12 Use of NFV then subsequently decreased after 2006 following the safety warning regarding a teratogenic impurity in the drug (Fig. 1c).13 While NNRTIs, like PIs, are also recommended for use in combination regimens with 2 NRTIs, this drug class (excluding entry inhibitors) was the least commonly dispensed prescription. This may be due to contraindications against nevirapine (NVP) and efavirenz (EFV) use during pregnancy (Fig. 1d).

The use of ARV combination regimens was evident throughout the study period (Fig. 2), also concordant with the US perinatal guidelines. Before 2003, the two most commonly used combination regimens were two NRTIs with either a PI or NNRTI. Thereafter, use of two NRTIs with an NNRTI decreased substantially, while two NRTIs with a PI increased to become the dominant combination regimen used from 2003 onwards, reaching a prevalence of 71% by 2007.

FIG. 2.

Temporal trends for antiretroviral combination regimes among 3083 HIV-infected pregnancies (2856 women) within the Medicaid Analytic eXtract.

Predictors of lack of ARV use during pregnancy

Results from the prediction model to identify characteristics associated with not using ARVs during pregnancy are shown in Table 2. Women who were more likely not to use any ARVs during pregnancy were those without a Medicaid claim indicative of HIV infection before pregnancy as compared to those with a claim prior to pregnancy [adjusted odds ratio (aOR)=1.88, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.46, 2.41], those with no dispensing of ARV drug prescription(s) before pregnancy (aOR=1.94, 95% CI: 1.48, 2.53), and those with no laboratory measure for CD4 count or viral load in the first trimester (aOR=2.95, 95% CI: 2.30, 3.77).

Table 2.

Predictors of Lack of ARV Use During Pregnancy Among HIV-Infected Pregnant Women Within the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (N=3083 Pregnancies)

| Univariable models | Final adjusted modela | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n (%) | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

| Age in years | |||||||

| 13–24 | 1122 (36) | 1.32 | 1.09, 1.59 | 0.004 | |||

| 25–34 | 1486 (48) | 1.00 | ref | ref | |||

| >35 | 475 (15) | 0.74 | 0.56, 0.98 | 0.04 | |||

| Race | |||||||

| Black | 2136 (69) | 1.00 | ref | ref | |||

| White | 426 (14) | 1.31 | 1.02, 1.69 | 0.03 | 1.66 | 1.27, 2.17 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 377 (12) | 1.38 | 1.06, 1.80 | 0.02 | 1.68 | 1.28, 2.20 | <0.001 |

| Other/unknown | 144 (5) | 2.20 | 1.53, 3.17 | <0.001 | 2.59 | 1.76, 3.83 | <0.001 |

| Diagnoses for co-morbiditiesb | 1105 (36) | 0.84 | 0.69, 1.00 | 0.06 | |||

| Diagnosis for depression | 558 (18) | 0.88 | 0.70, 1.10 | 0.26 | |||

| Diagnosis for mental health disorder | 455 (15) | 0.82 | 0.63, 1.05 | 0.12 | |||

| No Medicaid claim indicative of HIV infection before pregnancy | 1595 (52) | 2.98 | 2.46, 3.60 | <0.001 | 1.88 | 1.46, 2.41 | <0.001 |

| No dispensing of ARV drug prescription(s) before pregnancy | 1879 (61) | 2.86 | 2.33, 3.52 | <0.001 | 1.94 | 1.48, 2.53 | <0.001 |

| Diagnosis of possibly HIV-related illnesses | 40 (1.3) | 0.73 | 0.33, 1.62 | 0.44 | |||

| No laboratory measure for CD4 or viral load in the first trimester | 2125 (69) | 3.53 | 2.79, 4.47 | <0.001 | 2.95 | 2.303.77 | <0.001 |

| Number of distinct prescription dispensing for non-ARV drugs pre-pregnancy | 0.94 | 0.91, 0.98 | 0.001 | ||||

| Number of distinct outpatients visits for any reason pre-pregnancy | 0.99 | 0.97, 1.01 | 0.33 | ||||

| Number of distinct hospitalizations for any reason pre-pregnancy | 1.17 | 0.91, 1.49 | 0.21 | ||||

| Alcohol abuse | 116 (4) | 0.92 | 0.59, 1.44 | 0.72 | |||

| Drug abuse | 376 (12) | 0.92 | 0.70, 1.20 | 0.53 | |||

| Tobacco use | 202 (7) | 0.72 | 0.49, 1.06 | 0.09 | |||

ARV, antiretroviral; CI, confidence interval; HIV, human-immunodeficiency virus; OR, odds ratio.

Variables with a two-sided p value<0.20 in the univariable logistic regression models were included in the adjusted model, and those with a p value>0.10 in the adjusted model were removed one at a time, starting with the variable that had the largest p value.

Chronic hypertension, transient hypertension of pregnancy (gestational hypertension), pre-gestational diabetes, gestational diabetes, chronic renal disease, cerebrovascular disease, coronary heart disease, neoplasm, thrombophilia, obesity, alcohol abuse, drug abuse, tobacco use, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, depression, and mental health disorders.

Discussion

We have described temporal trends of ARV use among HIV-infected pregnant women in the US Medicaid program between 2000 and 2007. Based on our algorithm for HIV infection, we observed an overall HIV prevalence of 0.28%, ranging from 0% to 5.8% for different states and the District of Columbia. Regional variations were striking, including a substantial fraction of pregnant women not using any ARVs throughout pregnancy in some states. Among women with ARV use, utilization of ARVs during pregnancy in our study population was generally concordant with the US perinatal guidelines; however, there were also variations in state-specific prescription patterns.

The finding that 21% of HIV-infected women, with medical insurance before pregnancy, did not fill any ARV prescription during pregnancy is concerning. Since we have only prescription claims data, we cannot be certain how many patients were prescribed ARVs by their clinicians but never filled those prescriptions, so prescribing patterns may be better than our findings would indicate. On the other hand, many patients fill prescriptions but do not take the medications, as shown in studies that documented poor ARV adherence during pregnancy among substance users, and women with mental illnesses.14–17 Therefore, the actual proportion of women not using ARVs during pregnancy in our study population could be considerably higher than 21%. Moreover, women without health insurance or who enroll later in pregnancy in Medicaid probably had worse access to medications.

The prevalence of HIV among adults and adolescent females in the US is approximately 0.16% according to the US CDC HIV surveillance report. While we cannot directly compare our prevalence estimates to the CDC estimates because the populations are different, we observed similar rankings of HIV prevalence for individual states to that of the CDC (Appendix 2).

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study to assess patterns of ARVs prescribed to pregnant women in this indigent population in the US. Only one other study in the US, the Surveillance Monitoring for ART Toxicities (SMARTT) study, has comprehensively assessed use of ARVs during pregnancy;18 other studies on in utero ARV exposure only assessed a select group of ARVs.19,20 The SMARTT study used data from a prospective cohort of HIV-exposed but uninfected children enrolled from clinics located in research institutions.18 We compared trends of ARV use over time in SMARTT to our study and found that, while overall the prevalence of ARV use during pregnancy in MAX was always lower than in the SMARTT study, the two study populations had similar temporal trends of use over time (Appendix 4). This finding indicates that for indigent pregnant women who lived with HIV in the US between 2000 and 2007, those enrolled in Medicaid obtained ARV prescription drugs at proportions that were parallel to, but tended to be consistently lower than, those of women accessing care in referral research centers. Our results, however, differed from those observed in a cohort of pregnant women in a study conducted in Europe during the same time period.21 Results from the Italian study showed substantial decline in the use of ZDV and 3TC by 2007, and a rapid increase of tenofovir (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC) use between 2005 and 2007, with TDF reaching almost similar prevalence to ZDV (approximately 40%) by 2007. Differences between the two studies were also seen for other drug classes; NFV use was less common in the Italian cohort, while NVP use was higher compared to our cohort.

Regional variations were striking, including a substantial fraction of pregnant women not using any ARVs throughout pregnancy in some states. We estimated that up to 25% of pregnant women had no ARV prescription dispensing throughout the study years, whereas only 3.1% of infants had no in utero exposure to ARVs in the SMARTT study between 2003 and 2006. This high proportion of no ARV use during pregnancy might indicate poor coverage when compared to ARV use by 95% of HIV-infected pregnant women in countries such as Botswana in sub-Saharan Africa.22 Whether this is a reflection that physicians who cared for these women did not adequately prescribe ARV drugs, or that the women did not pick up their prescribed medications from the pharmacy, or that they accessed prenatal care late in pregnancy cannot be inferred from our data. In addition, even women without apparent ARV coverage might have received prophylactic treatment for transmission in the hospital around delivery. Further research is needed to characterize women who are not filling ARV prescriptions. For example, do they not use ARVs because they are unaware of their HIV status prior to pregnancy? Our results indicating that women who had no HIV-related Medicaid claims before pregnancy (i.e., no claims for HIV/AIDS, CD count, viral load, or ARVs) were the ones who were more likely to not have any ARV dispensing throughout pregnancy suggest barriers to care and emphasize the importance of accessing more granular data from this large population of pregnant women in future studies.

Our study had several limitations. First, lack of information on gestational length and LMP in MAX data could lead to misclassification of gestational timing of ARV drug dispensing. However, this source of misclassification is likely minor, considering the wide exposure window.10 Second, we used strict inclusion criteria that required continuous enrollment from 3 months prior to LMP through delivery. This possibly resulted in oversampling of multiparous, older women and those with chronic health conditions prior to pregnancy who may not be fully representative of the population of HIV-infected pregnant women in the US. Many women, including those who work and also undocumented individuals, qualify for Medicaid only after they become pregnant. Third, prescription dispensing is not a perfect measure of ARV use. In classifying combination regimes, for example, we did not assess whether prescriptions for individual ARV drugs were available to the woman simultaneously. However, the trends that we observed using pharmacy dispensing data are meaningful indicators for what is occurring in the population and can be used to inform both policy and clinical practice. We believe that our estimate of 21% is a conservative estimate for no ARV treatment during pregnancy because these are women not obtaining any ARV prescription. It is possible there are other women who do obtain at least one prescription, but then never return for refills. Furthermore, the strict criteria that we used to identify women with HIV infection, criteria that included ARV prescription dispensing, potentially led to conservative estimates of the overall HIV prevalence in this population. Most importantly, the criteria may have led to an oversampling of treated women and overestimate of coverage. By restricting our study sample to women with continuous Medicaid benefits from at least 3 months before pregnancy, we selected women who were most likely to have continuity of care. Overall these limitations suggest that if there is imprecision in our findings, it is likely in the direction of overestimating ARV treatment during pregnancy.

In conclusion, the patterns of ARV use that we observed in this Medicaid cohort consisting of 3083 HIV-infected pregnancies from 43 US states showed that the treatment experience of the women filling prescriptions is concordant with the US perinatal guidelines. However, lack of ARV use during pregnancy was alarmingly common. Variations in state-specific Medicaid programs, HIV-infected populations, or entrance into prenatal care may result in differential access to or utilization patterns of ARV drugs.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

The state-specific prevalence of HIV among 1,106,757 pregnancies (955,251 women) in the Medicaid Analytic Extract Pregnancy Cohort: 2000–2007.

Appendix 2.

Comparison of HIV Prevalence Estimates from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX)

| Estimated number of persons living with a diagnosis of HIV | Estimated number of HIV-infected pregnant women (2000–2007) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDC REPORT 2006a (females, all races/ethnicities, ages 13–55+ years) | MAX Estimates (pregnant women, 13–49 years old) | |||

| State | CDC prevalence | CDC ranks | MAX prevalence | MAX ranks |

| Alabama | 0.1381 | 12 | 0.3657 | 13 |

| Alaska | 0.0547 | 24 | 0 | 45.5 |

| Arizona | 0.059 | 21 | Data N/Ab for AZ | |

| Arkansas | 0.0968 | 17 | 0.1416 | 27 |

| California | Data N/A for CA | 0.093 | 34 | |

| Colorado | 0.0537 | 25 | 0.0796 | 35 |

| Connecticut | 0.2399 | 5 | Data N/Ac for CT | |

| Delaware | Data N/A for DE | 0.4531 | 7 | |

| District of Columbia | Data N/A for DC | 5.8212 | 1 | |

| Florida | 0.3281 | 3 | 0.8092 | 4 |

| Georgia | 0.2048 | 7 | 0.5774 | 6 |

| Hawaii | Data N/A for HI | 0.079 | 36 | |

| Idaho | 0.0234 | 38 | 0.1419 | 26 |

| Illinois | 0.121 | 15 | 0.1988 | 19 |

| Indiana | 0.0557 | 23 | 0.1679 | 23 |

| Iowa | 0.024 | 37 | 0.1226 | 31 |

| Kansas | 0.038 | 32 | 0.0594 | 38 |

| Kentucky | 0.0417 | 29 | 0.0419 | 39 |

| Louisiana | 0.2563 | 4 | 0.6544 | 5 |

| Maine | 0.0295 | 35 | 0.0765 | 37 |

| Maryland | Data N/A for MD | 0.9043 | 2 | |

| Massachusetts | Data N/A for MA | 0.3903 | 10 | |

| Michigan | 0.0699 | 18 | Data N/Ad for MI | |

| Minnesota | 0.0562 | 22 | 0.1623 | 24 |

| Mississippi | 0.1969 | 8 | 0.3661 | 12 |

| Missouri | 0.0658 | 19 | 0.182 | 20 |

| Nebraska | 0.0446 | 28 | 0.1686 | 22 |

| Nevada | 0.1027 | 16 | 0.2523 | 18 |

| New Hampshire | 0.0478 | 26 | 0.1596 | 25 |

| New Jersey | 0.3321 | 2 | 0.3817 | 11 |

| New Mexico | 0.0341 | 33 | 0.0257 | 42 |

| New York | 0.4693 | 1 | 0.886 | 3 |

| North Carolina | 0.166 | 9 | 0.3948 | 9 |

| North Dakota | 0.0115 | 40 | 0.0324 | 40 |

| Ohio | 0.062 | 20 | 0.1265 | 30 |

| Oklahoma | 0.0474 | 27 | 0.0299 | 41 |

| Oregon | Data N/A for OR | 0.1062 | 33 | |

| Pennsylvania | 0.1498 | 11 | 0.1747 | 21 |

| Rhode Island | Data N/A for RI | 0.3306 | 15 | |

| South Carolina | 0.2216 | 6 | 0.3319 | 14 |

| South Dakota | 0.0299 | 34 | 0.133 | 28 |

| Tennessee | 0.129 | 14 | 0.3057 | 16 |

| Texas | 0.1316 | 13 | 0.2735 | 17 |

| Utah | 0.0292 | 36 | 0.0232 | 43 |

| Vermont | Data N/A for VT | 0 | 45.5 | |

| Virginia | 0.1548 | 10 | 0.4215 | 8 |

| Washington | Data N/A for WA | 0.1323 | 29 | |

| West Virginia | 0.0411 | 30 | 0 | 45.5 |

| Wisconsin | 0.0394 | 31 | 0.1194 | 32 |

| Wyoming | 0.0189 | 39 | 0 | 45.5 |

Arizona was not included in the cohort of pregnancies in MAX because of inaccurate personal identifiers.

Data was not available in the cohort of pregnancies in MAX since the authors who created the cohort were unable to identify matching algorithm between moms and infants.

All pregnancies from Michigan were excluded in the cohort of pregnancies in MAX because claims for capitated, FFS, and traditional enrollees were implausibly low.

Note: There is no information on Montana because data was not available from both CDC and MAX.

Spearman correlation coefficient of the ranks = 0.87, p value <0 .0001.

Appendix 3.

The state-specific prevalence of ARV prescription dispensing during pregnancy among 3083 HIV-infected pregnancies (2856 women) in the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX): 2000–2007.

Appendix 4.

Comparison of temporal trends for ARV use during pregnancy among HIV-infected pregnancies in MAX and those in the SMARRT study: 2000–2007. ARV = antiretroviral therapy; LMP = last menstrual period; NRTI = nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; NNRTI = non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI = protease inhibitor. *Trends of ARV use during pregnancy in the Surveillance Monitoring for ART Toxicities (SMARRT) study. ** Trends of ARV use during pregnancy within the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child and Human Development (NICHD) [R01HD056940-01]. We are grateful to Raymond Griner who shared with us aggregate data from the Surveillance Monitoring for ART Toxicities (SMARTT) study to make Appendix 4.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist. Dr. Hernandez-Diaz has consulted for Novartis and GSK_Biologics for unrelated issues. Dr. Palmsten was supported by Training Grant T32HD060454 in Reproductive, Perinatal and Pediatric Epidemiology from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health. The Pharmacoepidemiology Program at the Harvard School of Public Health received funding from Pfizer and Asisa.

References

- 1.Towards the elimination of mother to child transmission of HIV Report of a WHO technical consultation. 9–11November2010. Geneva, Switzerland: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/elimination_report/en/index.html Accessed December5, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Achievements in public health. Reduction in perinatal transmission of HIV infection–United States, 1985–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2006;55:592–597 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Public health service task force recommendations for the use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant women infected with HIV-1 for maternal health and for reducing perinatal HIV-1 transmission in the United States January30, 1998. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/PDF/rr/rr4702.pdf Accessed November28, 2013

- 4.Panel on treatment of HIV-infected pregnant women and prevention of perinatal transmission Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-1 infected women for maternal health and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/PerinatalGL.pdf Accessed November28, 2013

- 5.U.S. food and drug administration Antiretroviral drugs used in the treatment of HIV infection. http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/byaudience/forpatientadvocates/hivandaidsactivities/ucm118915.htm Accessed December4, 2013

- 6.Kaiser family foundation Medicaid and HIV: A national analysis. October2011. http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8218.pdf Accessed December5, 2013

- 7.Markus AR, Rosenbaum S. The role of Medicaid in promoting access to high-quality, high-value maternity care. Womens Health Issues 2010;20:S67–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid services Medicaid analytic eXtract (MAX) General Information. https://www.cms.gov/MedicaidDataSourcesGenInfo/07_MAXGeneralInformation.asp Accessed December5, 2013

- 9.Palmsten K, Huybrechts KF, Mogun H, et al. Harnessing the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) to evaluate medications in pregnancy: Design considerations. PLoS One 2013;8:e67405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Margulis AV, Setoguchi S, Mittleman MA, Glynn RJ, Dormuth CR, Hernandez-Diaz S. Algorithms to estimate the beginning of pregnancy in administrative databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013;1:16–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneeweiss S, Seeger JD, Maclure M, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Performance of comorbidity scores to control for confounding in epidemiologic studies using claims data. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:854–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs in pregnant HIV-1-infected women for maternal health and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV-1 transmission in the United States: October, 122006. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/PerinatalGL000616.pdf Accessed December5, 2013

- 13.DHHS Perinatal Panel Notice on Nelfinavir FDA-Pfizer Letter September11, 2007. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/PeriNFVNotice.pdf Accessed December5, 2013

- 14.Bardeguez AD, Lindsey JC, Shannon M, et al. Adherence to antiretrovirals among US women during and after pregnancy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48:408–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapetanovic S, Christensen S, Karim R, et al. Correlates of perinatal depression in HIV-infected women. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2009;23:101–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreitchmann R, Harris DR, Kakehasi F, et al. Antiretroviral adherence during pregnancy and postpartum in Latin America. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:486–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Anderson J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during and after pregnancy in low-income, middle-income, and high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS 2012;26:2039–2052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griner R, Williams PL, Read JS, et al. In utero and postnatal exposure to antiretrovirals among HIV-exposed but uninfected children in the United States. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011;25:385–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brogly S, Williams P, Seage GR, 3rd, et al. Antiretroviral treatment in pediatric HIV infection in the United States: From clinical trials to clinical practice. JAMA 2005;293:2213–2220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel K, Shapiro DE, Brogly SB, et al. Prenatal protease inhibitor use and risk of preterm birth among HIV-infected women initiating antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy. J Infect Dis 2010;201:1035–1044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Floridia M, Ravizza M, Guaraldi G, et al. Use of specific antiretroviral regimens among HIV-infected women in Italy at time of conception: 2001–2011. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011;26:439–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UNICEF Botswana PMTCT fact sheet 2010. http://www.unicef.org/aids/files/Botswana_PMTCTFactsheet_2010.pdf Accessed December1, 2013