Abstract

BACKGROUND

Heart failure is a leading cause of hospital admission and readmission in older adults. The new United States healthcare reform law has created provisions for financial penalties for hospitals with higher-than-expected 30-day all-cause readmission rates for hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years with heart failure. We examined the effect of digoxin on 30-day all-cause hospital admission in older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction.

METHODS

In the main Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, 6800 ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure (ejection fraction ≤45%) were randomly assigned to digoxin or placebo. Of these, 3405 were ≥65 years (mean age, 72 years, 25% women, 11% non-whites). The main outcome in the current analysis was 30-day all-cause hospital admission.

RESULTS

In the first 30 days after randomization, all-cause hospitalization occurred in 5.4% (92/1693) and 8.1% (139/1712) of patients in the digoxin and placebo groups, respectively, (hazard ratio {HR} when digoxin was compared with placebo, 0.66; 95% confidence interval {CI}, 0.51–0.86; p=0.002). Digoxin also reduced both 30-day cardiovascular (3.5% vs. 6.5%; HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.38–0.72; p<0.001) and heart failure (1.7 vs. 4.2%; HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.26–0.62; p<0.001) hospitalizations, with similar trends for 30-day all-cause mortality (0.7% vs. 1.3%; HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.27–1.11; p=0.096). Younger patients were at lower risk of events but obtained similar benefits from digoxin.

CONCLUSIONS

Digoxin reduces 30-day all-cause hospital admission in ambulatory older patients with chronic systolic heart failure. Future studies need to examine its effect on 30-day all-cause hospital readmission in hospitalized patients with acute heart failure.

Keywords: Digoxin, heart failure, 30-day all-cause hospital admission

Heart failure is a leading cause of hospital admission and readmission for Medicare beneficiaries, many of which are considered potentially preventable.1,2 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), the new United States healthcare reform law, has identified 30-day all-cause hospital readmission in hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years of age as a target outcome for reduction of Medicare costs.3 The law requires the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to reduce payments to hospitals with excess readmissions effective for discharges beginning on October 1, 2012.4 The New York Times recently reported that Medicare has already imposed financial penalties against 2217 hospitals.5 Heart failure is one of three conditions for which the law is currently being implemented (the other two being acute myocardial infarction and pneumonia) and of the three, heart failure has the highest 30-day readmission rate.2

In the Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, digoxin led to a substantial reduction in hospitalization due to heart failure over the mean follow-up of 37 months, though its effect on all-cause hospital admission was more modest.6-8 However, the effect of digoxin on all-cause hospitalization during the first 30-days after randomization has not yet been reported. Although patients in the DIG trial were ambulatory and had chronic heart failure, because of digoxin’s favorable effect on hemodynamics, it has been suggested that it may also improve outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and those recently discharged after such a hospitalization.9 Therefore, the focus of the current analysis was to examine the effect of digoxin on 30-day all-cause hospital admission in older, potentially Medicare-eligible, adults with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the main DIG trial.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Patients

The main DIG trial was a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial of digoxin in chronic heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction. The rationale, design, and results of which have been previously reported.6,10 Briefly, in the main DIG trial, 6800 ambulatory chronic heart failure (ejection fraction ≤45%) patients in normal sinus rhythm from United States and Canada were randomized to receive either digoxin or placebo during 1991-1993 and were followed for an average of 37 months.6 The diagnosis of heart failure was based on current or past clinical symptoms, signs, or radiologic evidence of pulmonary congestion and ejection fraction was assessed by using radionuclide left ventriculography, left ventricular contrast angiography, or two-dimensional echocardiography. Most patients were receiving background therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and diuretics. Although data on beta-blocker use were not collected, the rate of beta-blocker use would be expected to be low, as these drugs were not yet approved for use in heart failure. Of the 6800 patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the main trial, 3405 (50%) were 65 years of age or older. The current study is based on a public-use copy of the DIG data obtained from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, which also sponsored the DIG trial.

Outcomes

The primary outcome in the main DIG trial was all-cause mortality. For the current analysis, we used hospitalization due to all-causes occurring during the first 30 days after randomization as our main outcome of interest. We also studied other outcomes that included 30-day cardiovascular and heart failure hospitalizations, 30-day all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortalities, and the composite outcome of 30-day all-cause hospitalization or mortality. Causes of death or hospitalization were classified by DIG investigators, who were blinded to the patient’s study-drug assignment, by review of medical record and interview of patients’ relatives. Vital status of patients was collected up to December 31, 1995 and was 98.9% complete.11

Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient characteristics by randomization are displayed as mean (±SD) or percentage and compared using Pearson’s Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Kaplan-Meier and Cox proportional hazards analyses were used to determine the effect of digoxin on various outcomes. Because patients were randomized to receive digoxin or placebo, and because the subset of older patients used in the current analysis were balanced on all measured baseline characteristics, our primary Cox regression models did not adjust for baseline covariates. However, we conducted sensitivity analyses in which we adjusted our Cox models for all key baseline demographics, morbidity and treatment characteristics presented in Table 1. In addition, to examine the effect of randomized treatment, we examined the effect of digoxin on 30-day all-cause admission in all 6800 patients with systolic heart failure in the main DIG trial that also included younger patients. Although the new health care reform law specifically targets older heart failure patients, this allowed us to examine the effect of digoxin in younger heart failure patients, who also have high rates of hospitalization. All statistical tests were two-tailed with a p-value <0.05 considered significant. SPSS-20 for Windows (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY) was used for statistical analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the subset of 3405 ambulatory patients aged 65 years or older with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the main Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial, according to randomization to digoxin or placebo

| Variables | Placebo | Digoxin | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) or mean (±SD) | (n=1712) | (n=1693) | |

| Age (years) | 72 (±5) | 72 (±5) | 0.974 |

| Female | 426 (25%) | 415 (25%) | 0.802 |

| Non-white | 194 (11%) | 180 (11%) | 0.514 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.2 (±4.7) | 25.9 (±4.5) | 0.040 |

| Duration of heart failure (months) | 30 (±37) | 30 (±38) | 0.625 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction | 29 (±9) | 29 (±9) | 0.855 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction <25% | 541 (32%) | 546 (32%) | 0.684 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio | 0.54 (±0.08) | 0.54 (±0.07) | 0.385 |

| Cardiothoracic ratio >55% | 644 (38%) | 622 (37%) | 0.596 |

| New York Heart Association functional class | |||

| I | 192 (11%) | 211 (13%) | 0.599 |

| II | 918 (54%) | 878 (52%) | |

| III | 563 (33%) | 560 (33%) | |

| IV | 39 (2%) | 43 (3%) | |

| Signs or symptoms of heart failure | |||

| Dyspnea at rest | 386 (23%) | 358 (21%) | 0.323 |

| Dyspnea on exertion | 1323 (77%) | 1306 (77%) | 0.924 |

| Jugular venous distension | 259 (15%) | 247 (15%) | 0.658 |

| Pulmonary râles | 346 (20%) | 356 (21%) | 0.555 |

| Lower extremity edema | 359 (21%) | 348 (21%) | 0.766 |

| Pulmonary Congestion by chest x-ray | 266 (16%) | 286 (17%) | 0.283 |

| No of signs or symptoms of heart failure* | |||

| 0 | 14 (1%) | 12 (1%) | 0.525 |

| 1 | 28 (2%) | 41 (2%) | |

| 2 | 109 (6%) | 115 (7%) | |

| 3 | 150 (9%) | 141 (8%) | |

| ≥4 | 1411 (82%) | 1384 (82%) | |

| Comorbid conditions | |||

| Prior myocardial infarction | 1168 (68%) | 1154 (68%) | 0.969 |

| Current angina pectoris | 489 (29%) | 465 (28%) | 0.476 |

| Hypertension | 815 (48%) | 784 (46%) | 0.448 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 517 (30%) | 488 (29%) | 0.379 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1038 (61%) | 1045 (62%) | 0.513 |

| Primary cause of heart failure | |||

| Ischemic | 1293 (76%) | 1278 (76%) | 0.532 |

| Hypertensive | 156 (9%) | 146 (9%) | |

| Idiopathic | 190 (11%) | 208 (12%) | |

| Others | 73 (4%) | 61 (4%) | |

| Medications | |||

| Pre-trial digoxin use | 739 (43%) | 744 (44%) | 0.646 |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | 1605 (94%) | 1591 (94%) | 0.784 |

| Diuretics | 1405 (82%) | 1374 (81%) | 0.493 |

| Nitrates | 788 (46%) | 768 (45%) | 0.697 |

| Heart rate (beats per minute) | 78 (±12) | 78 (±12) | 0.445 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 128 (±20) | 128 (±20) | 0.643 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 74 (±11) | 74 (±11) | 0782 |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.37 (±0.40) | 1.37 (±0.39) | 0.938 |

| Daily dose of study medication, mg | |||

| 0.125 | 433 (25.3%) | 426 (25.2%) | 0.430 |

| 0.250 | 1197 (69.9%) | 1209 (71.5%) | |

| 0.375 | 69 (4.0%) | 46 (2.7%) | |

| 0.500 | 2 (0.1%) | 2 (0.1%) |

Clinical signs or symptoms included rales, elevated jugular venous pressure, peripheral edema, dyspnea at rest or on exertion, orthopnea, limitation of activity, S3 gallop, and radiologic evidence of pulmonary congestion present in past or present

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

The subset of main DIG patients 65 years or older (n=3405) had a mean age of 72 (SD ±5) years, 25% were women, 11% were non-whites and 1693 (49.8%) patients were receiving digoxin. Baseline characteristics of patients assigned to digoxin and placebo were similar except for a lower body mass index amongst those assigned to digoxin (Table 1).

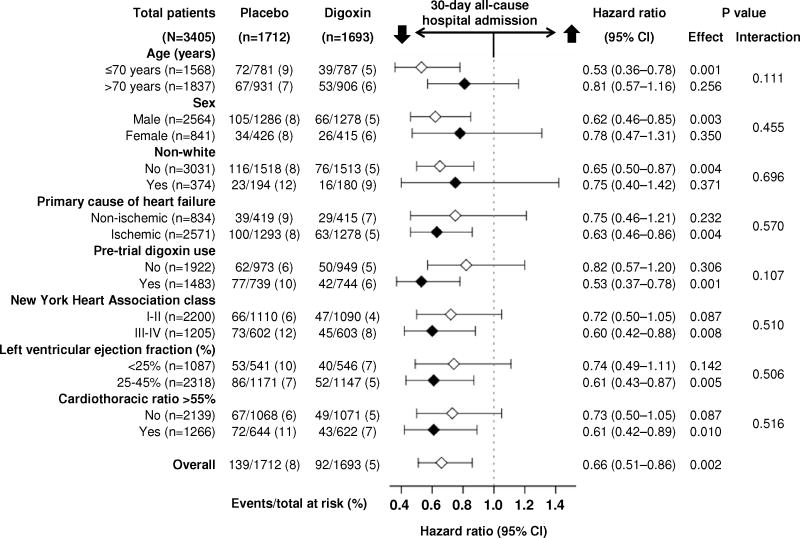

Digoxin and 30-day All-Cause Hospital Admission

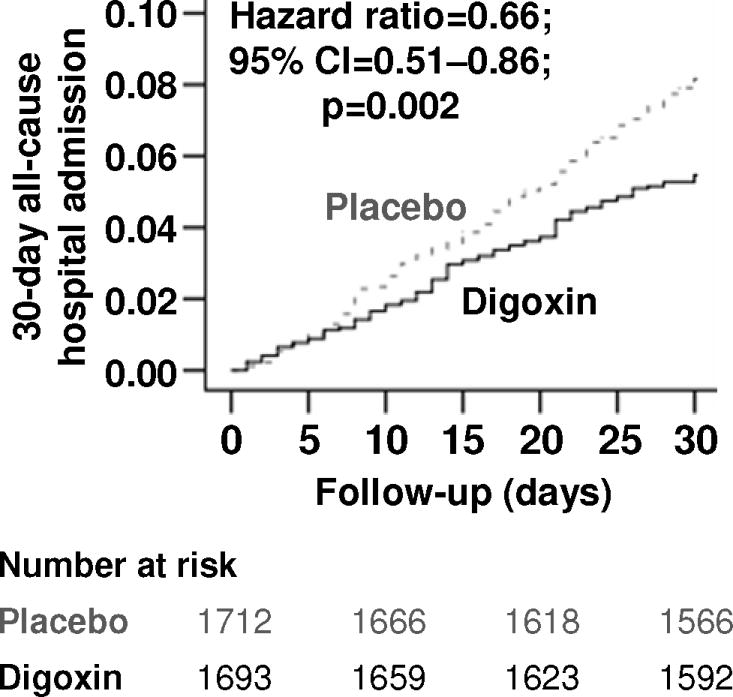

In the 30 days after randomization, all-cause hospital admission occurred in 8.1% and 5.4% of older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction assigned to placebo and digoxin, respectively (hazard ratio {HR} when digoxin was compared with placebo, 0.66; 95% confidence interval {CI}, 0.51–0.86; p=0.002; Table 2 and Figure 1). This effect of digoxin remained unchanged when adjusted for baseline characteristics presented in Table 1 (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.50–0.85; p=0.002). The effect of digoxin on 30-day all-cause hospital admission in various subgroups of older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction is displayed in Figure 2. Reductions in 30-day all-cause hospitalization were observed both for patients who continued pre-existing digoxin therapy or were newly initiated on digoxin compared to patients who were assigned to placebo (Figure 2). Digoxin also reduced the composite endpoint of all-cause mortality or all-cause hospitalization at 30 days after randomization (Table 2) and all-cause hospitalization at 60 days (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.63–0.91; p=0.003) and 90 days (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.63–0.88; p<0.001) after randomization.

Table 2.

Effect of digoxin on outcomes during 30 days after randomization in the subset of 3405 ambulatory patients aged 65 years or older with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the main Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial

| Outcomes | % (events)

|

Absolute risk difference* (%) | Hazard ratio† (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=1712) | Digoxin (n=1693) | ||||

| 30-day all-cause hospitalization | 8.1% (139) | 5.4% (92) | −2.7 | 0.66 (0.51–0.86) | 0.002 |

| 30-day cardiovascular hospitalization | 6.5% (112) | 3.5% (59) | −3.0 | 0.53 (0.38–0.72) | <0.001 |

| 30-day heart failure hospitalization | 4.2% (72) | 1.7% (29) | −2.5 | 0.40 (0.26–0.62) | <0.001 |

| 30-day all-cause mortality | 1.3% (22) | 0.7% (12) | −0.6 | 0.55 (0.27–1.11) | 0.096 |

| 30-day cardiovascular mortality | 1.1% (19) | 0.7% (12) | −0.4 | 0.64 (0.31–1.31) | 0.222 |

| 30-day heart failure mortality | 0.5% (9) | 0.1% (2) | −0.4 | 0.22 (0.05–1.04) | 0.056 |

| 30-day all-cause hospitalization or all-cause mortality | 8.7% (149) | 6.0% (102) | −2.7 | 0.69 (0.53–0.88) | 0.003 |

Absolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percent events in patients receiving placebo from those receiving digoxin

Hazard ratios comparing patients receiving digoxin versus those receiving placebo

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier plots for 30-day all-cause hospital admission by randomization to digoxin or placebo in the subset of 3405 ambulatory patients 65 years of age or older with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the main Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial

Figure 2.

Effect of digoxin on 30-day all-cause hospital admission in subgroups of 3405 ambulatory older patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the main Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial

Similarly, if all 6800 patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the main DIG trial are considered, regardless of age, digoxin reduced the risk of 30-day all-cause hospitalization (HR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.57–0.83; p<0.001; Table 3). In particular, among the 3395 patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction, aged <65 years, digoxin reduced the risk of 30-day all-cause hospitalization (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.55–0.93; p=0.012) and 30-day all-cause hospitalization or all-cause mortality (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.56–0.93; p=0.012).

Table 3.

Effect of digoxin on outcomes during 30 days after randomization in all 6800 ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the main Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) trial

| Outcomes | % (events)

|

Absolute risk difference* (%) | Hazard ratio† (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n=3403) | Digoxin (n=3397) | ||||

| 30-day all-cause hospitalization | 7.9% (270) | 5.5% (187) | −2.4 | 0.69 (0.57–0.83) | <0.001 |

| 30-day cardiovascular hospitalization | 6.1% (209) | 3.6% (122) | −2.5 | 0.58 (0.46–0.72) | <0.001 |

| 30-day heart failure hospitalization | 4.1% (140) | 1.6% (55) | −2.5 | 0.39 (0.29–0.53) | <0.001 |

| 30-day all-cause mortality | 1.1% (36) | 0.7% (23) | −0.4 | 0.64 (0.38–1.08) | 0.093 |

| 30-day cardiovascular mortality | 0.9% (32) | 0.6% (21) | −0.3 | 0.66 (0.38–1.14) | 0.134 |

| 30-day heart failure mortality | 0.4% (15) | 0.1% (5) | −0.3 | 0.33 (0.12–0.92) | 0.033 |

| 30-day all-cause hospitalization or all-cause mortality | 8.5% (288) | 6.0% (204) | −2.5 | 0.70 (0.59–0.84) | <0.001 |

Absolute risk differences were calculated by subtracting percent events in patients receiving placebo from those receiving digoxin

Hazard ratios comparing patients receiving digoxin versus those receiving placebo

Digoxin and Other 30-day Outcomes

Older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in the digoxin group had lower risk of 30-day cardiovascular (HR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.38–0.72; p<0.001) and 30-day heart failure (HR, 0.40; 95% CI, 0.26–0.62; p<0.001) hospitalizations, with similar trends for 30-day total mortality that did not reach statistical significance due to a low number of events (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.27–1.11; p=0.096; Table 2). Digoxin had similar effect on all 30-day outcomes in the overall DIG population without evidence of an age interaction (Table 3). Only four patients were hospitalized due to suspected digoxin toxicity within 30 days of randomization, of which three were from the digoxin group.

30-day All-Cause Hospital Admission in High-Risk Patients

The DIG protocol pre-specified patients with ejection fraction <25%, cardiothoracic ratio >55% or New York Heart Association class III-IV symptoms as a high-risk subgroup. About 67% of the older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in our study had one of the above three high-risk characteristics and these patients were more likely to have 30-day all-cause hospitalization (8.4% vs. 3.5% in the low-risk subgroup; p<0.001). Digoxin significantly reduced the risk of 30-day all-cause hospital admission in all 3 high-risk subgroups (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

Findings from the current analysis demonstrate that in the DIG trial the 30-day all-cause hospital admission rate among ambulatory older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction was low (8% in the placebo group, compared to 27% among hospitalized heart failure patients),2 yet this rate was further reduced by about one third amongst those assigned to digoxin. Although few deaths occurred during this period, they were numerically fewer in patients assigned to digoxin; consequently, the composite outcome of all-cause hospitalization or all-cause death at 30 days was also reduced substantially. The effect of digoxin persisted during 60 and 90 days after randomization, suggesting the early benefit of digoxin was not at the cost of later harm. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a significant reduction in 30-day all-cause hospital admission in older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction receiving digoxin. If the beneficial effect of digoxin on hospital admissions in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure from the pre-beta-blocker era of heart failure therapy presented in this report can be replicated in contemporary hospitalized older patients with acute heart failure, digoxin may play a role in reducing 30-day all-cause hospital readmission in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction.

In the main DIG trial, digoxin reduced the risk of all-cause hospitalization by 8% during 37 months of mean follow-up.6 In contrast, in the current analysis digoxin reduced the risk of 30-day all-cause hospital admission by a robust 34% in older patients. This large reduction of 30-day admissions is unlikely solely an age effect as we observed that digoxin reduced this risk by 29% in those aged <65 years. A potential explanation is that the beneficial effects of digoxin may be more marked during early follow-up. For example, although digoxin had no significant effect on mortality in the main DIG trial, it reduced the risk of all-cause mortality by 13% (HR, 0.87; p=0.043) during the first year after randomization.12 Another potential explanation is the preferential beneficial effect of digoxin on outcomes in high-risk subgroups.6 A protocol pre-specified subgroup analyses of the DIG trial demonstrated that during the first two years after randomization, digoxin reduced the risk of all-cause hospitalization by 16% (HR, 0.84; p<0.001) in high-risk patients, but not in those in the low-risk subgroup (HR, 1.06; p=0.355).13 Two thirds of the older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction in our study belonged to the high-risk subgroups who also had higher risk for 30-day all-cause hospitalization. It is also possible that part of the differences in 30-day admissions was mediated by an adverse effect of digoxin withdrawal.14,15 Although there was no significant interaction, the effect of digoxin on 30-day all-cause hospital admission was more pronounced in the subgroup receiving prior digoxin therapy (Figure 2). However, prior digoxin use may also be a marker of high risk. Treatment effect is often more pronounced in subgroups with higher baseline risk,16 and the observed effect of digoxin was greater in other high-risk subgroups (Figure 2).

Few randomized clinical trials of chronic heart failure patients have examined the effect of pharmacotherapy on 30-day all-cause hospital admission after randomization and most such data are based on patients with acute decompensated heart failure. Although there is some evidence of early salutary effects of renin-angiotensin inhibition and beta-blockade on heart failure hospitalization,17,18 data on 30-day all-cause hospitalization are lacking. Eplerenone, a selective aldosterone blocker, tended to reduce 30-day heart failure hospitalization in patients with post-acute myocardial infarction and systolic heart failure, but its effect on 30-day all-cause hospital admission was not reported.19 In hospitalized heart failure patients, discharge prescriptions for angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and beta-blockers have been shown to be associated with lower risk of 60- and 90-day post-discharge mortality or rehospitalization, but data on 30-day all-cause hospital readmission or association with digoxin use were not presented.20 Findings from studies of short-term intravenous therapies in hospitalized patients with acute decompensated heart failure suggest that in general these drugs do not have beneficial effects on 30-day hospital readmission.21-23 Many current heart failure performance measures also do not seem to be associated with lower hospital readmission rates.2,24

Preventable hospital readmissions account for nearly one fifth of Medicare payments to hospitals and heart failure is the leading cause of hospital readmission in the United States.2 Findings from this study suggest that digoxin, an old, inexpensive and well-tolerated drug with proven efficacy for reduction in heart failure hospitalization,6 also reduces 30-day all-cause hospital admission rates in ambulatory patients with chronic heart failure. However, hospitalized heart failure patients are characteristically and prognostically different from ambulatory heart failure patients. About 27% of hospitalized heart failure patients are readmitted within 30 days of hospital discharge,2 which is much higher than the 8% hospitalization rate observed in the current study. Worsening heart failure is the most frequent reason for hospital readmission during the first 30 days after discharge (37%), followed by pneumonia (5%) and renal failure (4%).2 In our study, worsening heart failure was also the primary reason for hospital admissions during the first 30 days after randomization accounting for 52% (72/139) of all hospital admission in the placebo group, followed by non-heart failure cardiovascular causes. In our study, patients assigned to digoxin had less than half the rate of admission for heart failure by 30 days. Considering that the effect of digoxin on heart failure hospital admission was more profound in high-risk subgroups of ambulatory chronic heart failure patients, it is plausible that digoxin would also reduce 30-day all-cause hospital readmission in hospitalized patients with acute heart failure who would be expected to be at higher risk for hospital readmission.

Our study has several limitations. The current analysis was restricted to ambulatory older patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. In the general community, over half of the hospitalized older heart failure patients have preserved ejection fraction.25 Although digoxin appears to reduce the risk of heart failure hospitalization in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction,26 whether it would also reduce 30-day hospital readmission in such patients remains unknown. DIG participants were not receiving beta-blockers, which may limit generalizability of these findings to current practice since medical and device-based therapy for systolic heart failure has evolved since the DIG trial. However, systolic heart failure patients in early randomized clinical trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and aldosterone antagonists also did not receive beta-blockers,27,28 and yet these drugs have later been shown to improve outcomes in those receiving beta-blockers.29,30 Future prospective randomized clinical trials need to examine whether digoxin would also reduce the risk of 30-day all-cause hospital readmission in contemporary hospitalized older heart failure patients receiving evidence-based therapy with neurohormonal blocking agents.

In conclusion, digoxin reduced the risk of 30-day all-cause, cardiovascular and heart failure-related hospital admissions in ambulatory older adults with chronic systolic heart failure. If these findings can be replicated in hospitalized older patients with acute heart failure, digoxin may provide an inexpensive tool to reduce 30-day all-cause hospital readmission for this large and growing population.

Acknowledgments

The Digitalis Investigation Group (DIG) study was conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with the DIG Investigators. This Manuscript was prepared using a limited access dataset obtained from the NHLBI and does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the DIG Study or the NHLBI.

Footnotes

Embargoed materials: Abstract was presented at a Late-Breaking Clinical Trials Session at the 2013 American College of Cardiology Scientific Sessions on March 11, 2013 in San Francisco, CA

Contributors:

AA, RCB, JLF, GCF conceived the study hypothesis and design, and AA, RCB, GCF and KP wrote the first draft. AA and KP conducted statistical analyses in collaboration with IBA. All authors interpreted the data, participated in critical revision of the paper for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the article. AA, KP and IBA had full access to the data.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jiang HJ, Russo CA, Barrett ML. HCUP Statistical Brief #72. U S Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Rockville, MD: Apr, 2009. Nationwide Frequency and Costs of Potentially Preventable Hospitalizations, 2006. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb72.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;360:1418–1428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone J, Hoffman GJ. Congressional Research Service Report for Congress. Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress; Washington, DC: 2010. Medicare Hospital Readmissions: Issues, Policy Options and PPACA. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [December 28, 2012];Readmissions Reduction Program. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html.

- 5.Rau J. Hospitals Face Pressure to Avert Readmissions. [December 2, 2012];The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/27/health/hospitals-face-pressure-from-medicare-to-avert-readmissions.html?_r=0, Published:November 26, 2012;Health.

- 6.The Digitalis Investigation Group Investigators. The effect of digoxin on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199702203360801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hood WB, Jr, Dans AL, Guyatt GH, Jaeschke R, McMurray JJ. Digitalis for treatment of congestive heart failure in patients in sinus rhythm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002901.pub2. CD002901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gheorghiade M, van Veldhuisen DJ, Colucci WS. Contemporary use of digoxin in the management of cardiovascular disorders. Circulation. 2006;113:2556–2564. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.560110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gheorghiade M, Braunwald E. Reconsidering the role for digoxin in the management of acute heart failure syndromes. JAMA. 2009;302:2146–2147. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Digitalis Investigation Group. Rationale, design, implementation, and baseline characteristics of patients in the DIG trial: a large, simple, long-term trial to evaluate the effect of digitalis on mortality in heart failure. Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:77–97. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00065-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins JF, Howell CL, Horney A. Invest DIG. Determination of vital status at the end of the DIG trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2003;24:726–730. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed A, Waagstein F, Pitt B, et al. Effectiveness of digoxin in reducing one-year mortality in chronic heart failure in the Digitalis Investigation Group trial. Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gheorghiade M, Patel K, Flippatos GS, et al. Effect of oral digoxin in high-risk heart failure patients: a pre-specified subgroup analysis of the DIG trial. Euro J Heart Fail. 2013;15:551–9. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Packer M, Gheorghiade M, Young JB, et al. Withdrawal of digoxin from patients with chronic heart failure treated with angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors. RADIANCE Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307013290101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uretsky BF, Young JB, Shahidi FE, Yellen LG, Harrison MC, Jolly MK. Randomized study assessing the effect of digoxin withdrawal in patients with mild to moderate chronic congestive heart failure: results of the PROVED trial. PROVED Investigative Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:955–962. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90403-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothwell PM. Treating individuals 2. Subgroup analysis in randomised controlled trials: importance, indications, and interpretation. Lancet. 2005;365:176–186. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17709-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garg R, Yusuf S. Overview of randomized trials of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure. Collaborative Group on ACE Inhibitor Trials. JAMA. 1995;273:1450–1456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krum H, Roecker EB, Mohacsi P, et al. Effects of initiating carvedilol in patients with severe chronic heart failure: results from the COPERNICUS Study. JAMA. 2003;289:712–718. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.6.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitt B, White H, Nicolau J, et al. Eplerenone reduces mortality 30 days after randomization following acute myocardial infarction in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Association between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;297:61–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Connor CM, Starling RC, Hernandez AF, et al. Effect of nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:32–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packer M, Carver JR, Rodeheffer RJ, et al. Effect of oral milrinone on mortality in severe chronic heart failure. The PROMISE Study Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1468–1475. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111213252103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Davison BA, et al. Serelaxin, recombinant human relaxin-2, for treatment of acute heart failure (RELAX-AHF): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;381:29–39. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61855-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mulvey GK, Wang Y, Lin Z, et al. Mortality and readmission for patients with heart failure among U.S. News & World Report’s top heart hospitals. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:558–565. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.826784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fonarow GC, Stough WG, Abraham WT, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of patients with preserved systolic function hospitalized for heart failure: a report from the OPTIMIZE-HF Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:768–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ahmed A, Rich MW, Fleg JL, et al. Effects of digoxin on morbidity and mortality in diastolic heart failure: the ancillary digitalis investigation group trial. Circulation. 2006;114:397–403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. The effect of spironolactone on morbidity and mortality in patients with severe heart failure. Randomized Aldactone Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:709–717. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The SOLVD Investigators. Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Granger CB, McMurray JJ, Yusuf S, et al. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. Lancet. 2003;362:772–776. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zannad F, McMurray JJ, Krum H, et al. Eplerenone in patients with systolic heart failure and mild symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]