Abstract

Radical and repeated cone biopsies are associated with a high risk of spontaneous preterm birth. A 30-year-old gravida 1 presented with a spontaneous dichorionic twin pregnancy. She had a history of two radical surgical conizations. By speculum examination, no cervical tissue was detected. A history-indicated transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage was performed at 12 + 4/7 gestational weeks because of assumed cervicoisthmic insufficiency. The pregnancy continued until 34 + 3/7 weeks when the patient developed preeclampsia indicating Cesarean delivery. Transabdominal cerclage in twin pregnancy has rarely been described, but it may be considered in case of extreme cervical shortening after radical cervical surgery, as it would in singleton pregnancy.

1. Introduction

Benson and Durfee first described transabdominal cerclage in 1965 [1]. In 1987, Wallenburg and Lotgering [2] and later Lotgering et al. [3] discussed indications for transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage (TAC) and suggested its use in case of suspected cervical insufficiency in women with a very short cervix to allow effective transvaginal cerclage. This may include the congenitally short or amputated cervix.

At present, few case reports (Table 1) have described the use of TAC in twin pregnancies. We report on a case in which TAC was performed in a nulliparous patient with twin pregnancy and a history of two radical surgical conizations.

Table 1.

Summary of publications on transabdominal cerclage in twin pregnancies.

| Authors (number of twin pairs) | Technique | Gestational week of placement | Pregnancy | Gestational week of delivery | Outcome | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cammarano et al. [5] (2) | TAC | 14 13 |

3rd 3rd |

38 33 4/7 |

2 alive 2 alive |

None |

|

| ||||||

| Işçi et al. [6] (1) | TAC | In former pregnancy | 2nd | 33 | 2 alive | Polycystic ovary syndrome, congenital hypoplasia, ovary tumor IVF/clomiphene citrate treatment |

|

| ||||||

| Lee et al. [7] (1) | TAC | 12 5/7 | 1st | 30 5/7 | 2 alive | History of microinvasive adenocarcinoma of the cervix with VRT Vaginal spotting (29 weeks) contractions, vaginal bleeding (30 weeks) |

|

| ||||||

| Olatunbosun et al. [8] (2) | TAC | 12–14 | ? | 20 37 |

2 perinatal deaths 1 stillborn, 1 alive |

Preterm labor ? |

|

| ||||||

| Olawaiye et al. [9] (1) | TAC | Preconceptional | 1st | 36 | 2 alive | Cerclage as part of VRT IVF/ET |

|

| ||||||

| Pereira et al. [10] (1) | LTCC | Preconceptional | 2nd | 38 | 2 alive | Hysteroscopic metroplasty (uterus subseptus) |

|

| ||||||

| Lotgering et al. [3] (7)* | TAC | End of 1st trimester | 25 (1) >32 (6) |

1 alive; 1 perinatal death 12 alive |

PPROM None |

|

*Personal communication, details not presented in the text.

ET: embryo transfer; IVF: in vitro fertilization; LTCC: laparoscopic transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage; PPROM: preterm premature rupture of membranes; TAC: transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage; VRT: vaginal radical trachelectomy.

2. Presentation of the Case

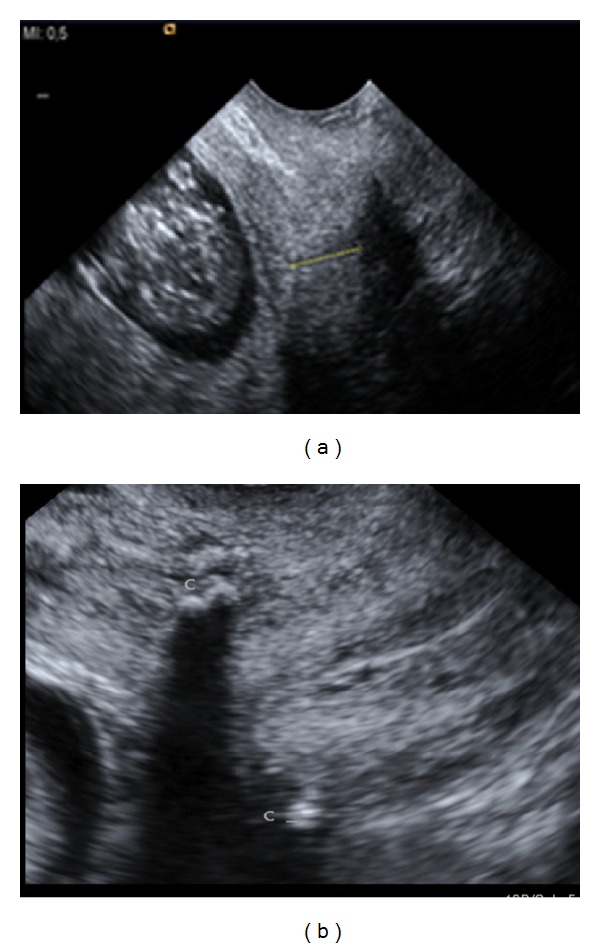

A 30-year-old primigravida with dichorionic/diamniotic (DC/DA) twins was referred to our unit of Marburg University at 11 weeks of gestation. Three years before, the patient had been exposed to two radical surgical conizations because of severe cervical dysplasia and carcinoma in situ, which was only completely removed after a second conization. Speculum examination showed a blind vaginal top without cervix. Transvaginal sonography (TVS) at 12 weeks demonstrated a short inner cervical length of 11.4 mm (below the 3rd centile), without funneling (Figure 1(a)).

Figure 1.

Inner cervical length of 11.4 mm at 12 + 4/7 gestational weeks before abdominal cerclage (a) and at 20 weeks after the transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage. The Mersilene band is shown as an echogenic structure at the cervicoisthmic junction (C) and seemed to have increased the cervical length to 25 mm (not shown).

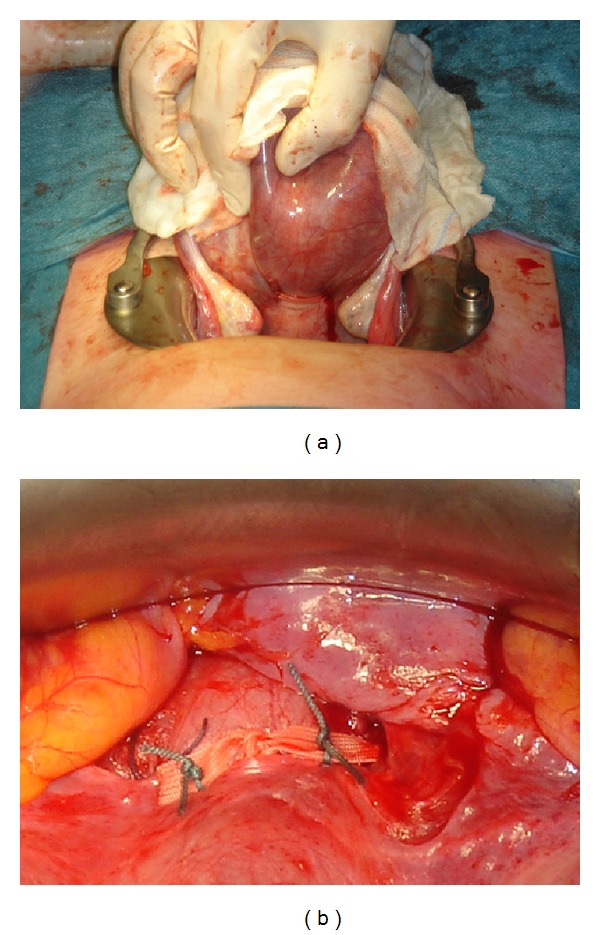

The patient was counseled for high risk of preterm delivery associated with short cervix and twin gestation, using the publication of Lotgering [4] as a handout. The advantages and disadvantages of expectant management, Arabin pessary, transvaginal cerclage, and transabdominal cerclage were discussed. In an effort to optimize chances to reach viable gestational age we elected to perform transabdominal cerclage. The operation took place at 12 4/7 weeks under general anesthesia at the Radboud University Nijmegen Medical School, Nijmegen, as previously described [2, 3]. In short, after exposing the uterus, the cervicoisthmic junction was visualized and the cerclage (5 mm wide Mersilene ribbon, Ethicon, Norderstedt, Germany) was inserted through the avascular triangle between the ascending and descending branches of the uterine artery on each side (Figures 2(a) and 2(b)). The patient was discharged three days after surgery. TVS showed a cervical length (CL) of 25 mm below the cerclage.

Figure 2.

Dorsal (a) and ventral (b) view of the Mersilene band, located at the cervicoisthmic junction. The band is tied on the anterior side of the cervix and the cut ends are fixed to the band with thin nonabsorbable sutures (b).

Pregnancy proceeded normally. Regular TVS showed no significant change of CL throughout pregnancy (Figure 1(b)). At 34 3/7 weeks of gestation the patient developed moderately severe preeclampsia. Cesarean delivery was performed, resulting in the birth of a healthy male and female infants with birth weights of 2465 g and 1930 g, respectively. Apgar scores were 7/8/9 and 6/8/8 and umbilical artery pH values were 7.31 and 7.26, respectively. The infants were admitted to the neonatal unit and experienced no complications. The Mersilene band was left in place as suggested by Cammarano et al. [5] for the benefit in any future pregnancy. Lochia flow was normal.

3. Discussion

One may question the validity of the decision to perform a cerclage in a woman with no history of preterm birth only because she had an internal 11 mm short cervix while she was carrying twins. On the one hand, the chance of preterm birth before 35 weeks is about 25% in women with singleton pregnancy and a cervical length of 11 mm, in the absence of a history of spontaneous preterm birth (SPTB) [11]. That risk can be reduced to 13% by cerclage [11]. The larger uterine distension in a twin pregnancy may be expected to increase the risk. On the other hand, however, cervical cerclage in twins is controversial to the extent that Berghella and Seibel-Seaman stated that there is no evidence that cerclages should be performed in any woman carrying a multiple gestation [12]. That statement is based on women who received transvaginal cerclage after cervical shortening, not on transabdominal cerclage in women with a cervix too short for transvaginal cerclage. In our patient we performed TAC because our patient and we considered the risk of expectant management too high.

There are different techniques of abdominal cerclages. The classic approach is by TAC during pregnancy, while some authors support the procedure prior to pregnancy [1, 5–10, 12–15]. More recently, laparoscopic transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage (LTCC) [10, 14] and even robotic techniques have been described [15]. In addition, one may consider performing TAC in the same session with trachelectomy performed for malignancy [16].

The main advantage of the classical TAC performed during pregnancy is that the cervix has reached its full pregnant size which allows for optimal tension of the cerclage ribbon at knotting and a reported take-home baby rate of 93% [3]. When the cerclage is performed in the nonpregnant state, one has to adjust for the estimated swelling of the cervix in the subsequent pregnancy, which may result in suboptimal tension during pregnancy. We know of women with TAC being too loose resulting in recurrent mid-pregnancy loss and women with TAC being too tight cutting through the cervix as a result of pressure necrosis. In the largest cohort study up to now, Lotgering et al. [3] reported a take-home baby rate of 93% and a rate of only 7% of SPTB before 32 weeks after TAC in 101 in women with suspected cervical insufficiency and a cervix too short for vaginal cerclage. This series included 7 twin pregnancies (personal communication F. Lotgering).

Data on TAC in twin pregnancies are scarce. A systematic review of the literature in PubMed and EMBASE for the match terms “twin pregnancy” and “transabdominal cerclage” revealed 6 publications [5–10] with 8 twin pregnancies. By inclusion of the 7 twin pregnancies from the dataset of Lotgering et al. [3], a total of 15 twin pregnancies with TAC were available for analysis. These cases resulted in 26/30 (87%) healthy infants and 4/30 (13%) perinatal deaths [5, 8] (Table 1). In one woman both twins died from extreme prematurity after SPTB at 20 weeks [8]. TAC was history-indicated in this case, because of failed vaginal cerclage in the previous pregnancy. Two other women delivered a stillborn and a viable infant, one after PPROM at 25 weeks [3] and the other at 37 weeks [8]. Notably, stillbirth is not a common finding in cervical insufficiency or cerclage. We admit that failed cases tend to be hidden for obvious purposes and frequently not published.

From the total group, 14/15 women had TAC by laparotomy, one by laparoscopic transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage (LTCC). Three of the 15 interventions took place before the index twin pregnancy, either preconceptionally or in a former pregnancy. The remaining operations took place during the index twin pregnancy and were performed between 12 and 14 gestational weeks. Gestational age at delivery ranged from 20 to 38 weeks: 1/15 at 20 weeks, 3/15 < 32 weeks, 4/15 between 32 and 37 weeks, and 7/15 after 37 weeks. There was no case of delayed interval delivery. Unfortunately, the study population is too small to allow a firm conclusion on a possible difference in outcome of twins compared to singletons after TAC.

Although TAC appears to be an efficient procedure in most women with cervical shortening, one may consider the risks of morbidity by performing two laparotomies. The first is required for the placement of the TAC and the second for the cesarean delivery of the baby. Alternatively, one may consider the possibility of the transvaginal cervicoisthmic cerclage (TCC) using a polypropylene sling as an alternative to the TAC in women presenting with previous cerclage failure. Deffieux et al. [17, 18] reported an overall neonatal survival rate of over 90% in patients with TCC. In this respect, TCC may be a useful alternative for this high-risk patient group.

In the absence of formal proof of efficacy of TAC in twin pregnancies, the decision to perform or not to perform a TAC in a woman at very high risk of immature or preterm delivery because of a severely damaged clinically not existing cervix will remain controversial. The limited data in twin pregnancies suggest that the results of TAC are comparable to those in singleton pregnancies and indications for TAC may be justifiable even in multiple gestations.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to report.

References

- 1.Beson RC, Durfee RB. Transabdominal cervicouterine cerclage during pregnancy for the treatment of cervical incompetency. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1965;25(2):145–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallenburg HCS, Lotgering FK. Transabdominal cerclage for closure of the incompetent cervix. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1987;25(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(87)90115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lotgering FK, Gaugler-Senden IPM, Lotgering SF, Wallenburg HCS. Outcome after transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006;107(4):779–784. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000206817.97328.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lotgering FK. Clinical aspects of cervical insufficiency. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 2007;7(supplement 1, article S17) doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-7-S1-S17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cammarano CL, Herron MA, Parer JT. Validity of indications for transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage for cervical incomptence. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1995;172(6):1871–1875. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91425-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Işçi H, Güdücü N, Yiğiter AB, Demirkiran F, Aygün M, Dünder I. Borderline micropapillary serous tumor of the ovary detected during a cesarean section due to a transabdominal cervico-isthmic cerclage in a patient with congenital cervical hypoplasia: a rare case. European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 2011;32(4):457–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee K-Y, Jun H-A, Roh J-W, Song J-E. Successful twin pregnancy after vaginal radical trachelectomy using transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;197(3):e5–e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olatunbosun O, Turnell R, Pierson R. Transvaginal sonography and fiberoptic illumination of uterine vessels for abdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2003;102(5):1130–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00228-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olawaiye A, Del Carmen M, Tambouret R, Goodman A, Fuller A, Duska LR. Abdominal radical trachelectomy: success and pitfalls in a general gynecologic oncology practice. Gynecologic Oncology. 2009;112(3):506–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pereira RMA, Zanatta A, Bianchi PHDM, Yadid IM, da Motta ELA, Serafini PC. Successful interval laparoscopic transabdominal cervicoisthmic cerclage preceding twin Gestation: a case report. The Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology. 2009;16(5):634–638. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berghella V, Keeler SM, To MS, Althuisius SM, Rust OA. Effectiveness of cerclage according to severity of cervical length shortening: a meta-analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010;35(4):468–473. doi: 10.1002/uog.7547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berghella V, Seibel-Seamon J. Contemporary use of cervical cerclage. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;50(2):468–477. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31804bddfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witt MU, Joy SD, Clark J, Herring A, Bowes WA, Thorp JM. Cervicoisthmic cerclage: transabdominal versus transvaginal approach. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009;201(1):105.e1–105.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burger NB, Einarsson JI, Brolmann HA, Vree FE, McElrath TF, Huirne JA. Preconceptional laparoscopic abdominal cerclage: a multicenter cohort study. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012;207(4):273.e1–273.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barmat L, Glaser G, Davis G, Craparo F. Da Vinci-assisted abdominal cerclage. Fertility and Sterility. 2007;88(5):1437.e1–1437.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van de Nieuwenhof HP, van Ham MAPC, Lotgering FK, Massuger LFAG. First case of vaginal radical trachelectomy in a pregnant patient. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2008;18(6):1381–1385. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2008.01193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deffieux X, de Tayrac R, Louafi N, et al. Transvaginal cervico-isthmic cerclage using polypropylene tape: surgical procedure and pregnancy outcome: Fernandez's procedure. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 2006;35(5, part 1):465–471. doi: 10.1016/s0368-2315(06)76418-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deffieux X, Faivre E, Senat M-V, Gervaise A, Fernandez H. Transvaginal cervicoisthmic cerclage using a polypropylene sling: pregnancy outcome. The Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research. 2011;37(10):1297–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]