Abstract

PURPOSE

To describe the long-term refractive error changes in children diagnosed with intermittent exotropia (IXT) in a defined population.

DESIGN

Retrospective, population-based observational study.

METHODS

Using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, the medical records of all children (<19 years) diagnosed with IXT as residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, from January 1, 1975 through December 31, 1994 were retrospectively reviewed for any change in refractive error over time.

RESULTS

One hundred eighty-four children were diagnosed with IXT during the 20-year study period; 135 (73.4%) had 2 or more refractions separated by a mean of 10 years (range, 1–27 years). The Kaplan-Meier rate of developing myopia in this population was 7.4% by 5 years of age, 46.5% by 10 years, and 91.1% by 20 years. There were 106 patients with 2 or more refractions separated by at least 1 year through 21 years of age, of which 43 underwent surgery and 63 were observed. The annual overall progression was −0.26 diopters (SD ± 0.24) without a statistically significant difference between the observed and surgical groups (P = .59).

CONCLUSION

In this population-based study of children with intermittent exotropia, myopia was calculated to occur in more than 90% of patients by 20 years of age. Observation versus surgical correction did not alter the refractive outcome.

Intermittent exotropia, characterized by an acquired, intermittent exodeviation, occurs in approximately 1% of healthy children in the United States1 and, given its predominance over esodeviations among Asian populations,2 may be the most prevalent form of strabismus worldwide. Although esotropia has been associated with hyperopia and anisometropia,3–8 the refractive error of children with divergent strabismus has not been as rigorously studied. The purpose of this study is to describe the refractive error outcomes in a population-based cohort of children diagnosed with intermittent exotropia over a 20-year period.

METHODS

The medical records of all patients younger than 19 years who were residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota, when diagnosed by an ophthalmologist as having intermittent exotropia between January 1, 1975 and December 31, 1994 were retrospectively reviewed. Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study. Potential cases of intermittent exotropia were identified using the resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project, a medical record linkage system designed to capture data on any patient–physician encounter in Olmsted County, Minnesota.9 The racial distribution of Olmsted County residents in 1990 was 95.7% Caucasian, 3.0% Asian American, 0.7% African American, and 0.3% each for Native American and other. The population of this county (106 470 in 1990) is relatively isolated from other urban areas, and virtually all medical care is provided to residents by Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Group, and their affiliated hospitals. Patients not residing in Olmsted County at the time of their diagnosis were excluded. Intermittent exotropia was defined in this study as an intermittent distance exodeviation of at least 10 prism diopters (PD) without an underlying or associated neurologic, paralytic, or anatomic disorder.

Data abstracted from the medical records included gender, family history of strabismus, birth weight, gestational age at birth, reported age at onset, and ocular findings. The angle of deviation was primarily determined by the prism and alternate cover technique at both distance and near, although some younger patients were measured by the Hirschberg or modified Krimsky techniques at near. The initial and subsequent refractions were determined in the majority of patients following the topical administration of 1% cyclopentolate in younger patients and by a manifest refraction for older patients. All refractions were converted into their spherical equivalent. Since no patient had greater than 1 diopter of anisometropia, the refractive errors of the right and left eyes were averaged. Myopia was defined in this study as more than or equal to −0.50 diopters. Follow-up was measured from the date of the initial refraction to the last examination at which the refractive error was recorded through August 31, 2007.

Continuous data are presented as a mean with a standard deviation and categorical data are presented as counts and percentages. Progression of refractive error was determined by measuring the difference between the initial and final refraction divided by the total follow-up time per patient through the age of 21 years. Comparisons between groups for continuous variables were completed using Wilcoxon rank sum tests and for categorical variables using Fisher exact tests. All statistical tests were 2-sided, and the threshold of significance was set at P = .05. The rate of developing myopia was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method.10

RESULTS

One hundred eighty-four patients were diagnosed with intermittent exotropia during the 20-year period. One hundred thirty-five of the 184 (73.4%) had 2 or more refractive error measurements separated by at least 1 year, the clinical findings of which are shown in Table 1. There were 44 (33%) male and 91 (67%) female patients. The mean age at diagnosis for the 135 was 5.6 years (range, 0.9 to 14.9 years). Amblyopia was present in 4 patients (3%). The mean initial angle of deviation was 20 prism diopters (range, 10 to 40 PD) and 14 PD (range, 0 to 45 PD) at distance and near, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Historical and Initial Clinical Characteristics of 135 Children With Intermittent Exotropia With 2 or More Refractive Error Measurements

| Characteristics | Findings |

|---|---|

| Number of boys (%)/number of girls (%) | 44 (33%)/91 (67%) |

| Mean age at diagnosis in years (range) | 5.6 (0.9 to 14.9) |

| Number (%) with amblyopia | 4 (3%) |

| Mean initial horizontal deviation at distance in prism diopters (range) | 20 (10 to 40) |

| Mean initial horizontal deviation at near in prism diopters (range) | 14 (0 to 45) |

| Number (%) with inferior oblique dysfunction | 19 (14%) |

| Number (%) with dissociated vertical deviation | 3 (2.2%) |

| Number (%) managed with over-minus correction | 6 (4.4%) |

| Number (%) managed with surgical correction | 54 (40%) |

| Mean follow-up in years (range) | 10.1 (1.0 to 27.1) |

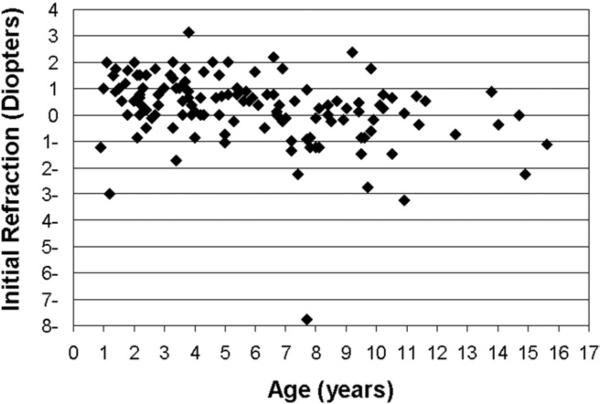

The initial refractive error of the 135 children is shown in Figure 1, with a mean value of +0.26 (range, −7.75 to +3.13) at a mean age of 5.6 years. Eighty-four patients (62.2%) were initially hyperopic at an average age of 5.0 years; 56 of them (67%) had less than 1 diopter of hyperopia. Thirty-nine of the 135 patients (28.9%) were initially myopic at a mean age at diagnosis of 7.6 years. The remaining 12 patients (8.9%) were plano at an average age of 5.2 years.

FIGURE 1.

Initial refractive error by age in 135 children with intermittent exotropia.

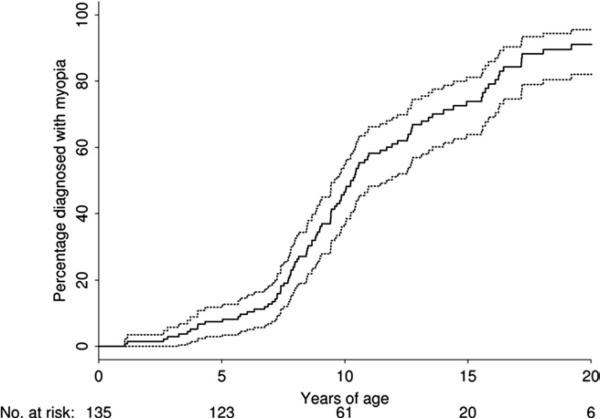

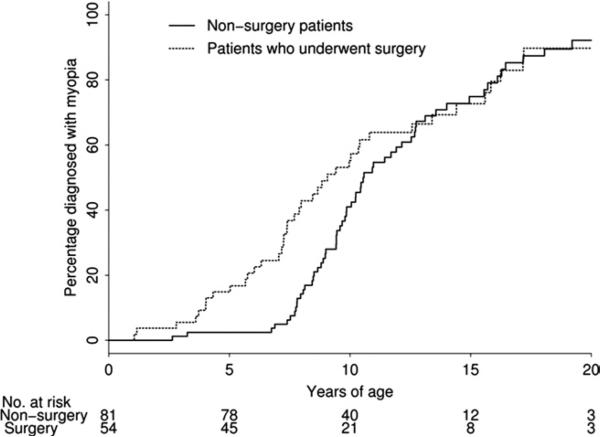

The study patients were followed for a mean of 10.1 years (range, 1.0 to 27.1 years). The final refractive error of the 135 children included myopia in 95 (70%), hyperopia in 34 (25%), and plano in 6 (4.4%), at a mean age of 15.9 years. The Kaplan-Meier rate of developing myopia in this population was 7.4% by 5 years of age, 46.5% by 10 years, and 91.1% by 20 years (Figure 2). Of the 135 children, 54 (40%) underwent surgical correction for IXT. The Kaplan-Meier rate of developing myopia in the surgery group versus the observation group is shown in Figure 3. There was no significant difference in the rate of myopic progression between the two groups (P = 0.16). Only 6 patients were treated with over-minus correction, but this group was too small for any statistical analyses.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimate of myopic progression by age (with 95% CI) in 135 children with intermittent exotropia.

FIGURE 3.

The Kaplan-Meier rate of myopic progression between 54 IXT patients who underwent surgery and 81 who were observed (P = .16).

To calculate the annual myopic progression, a subset of patients with 2 or more refractive error measurements separated by at least 1 year and measured before the age of 21 years was reviewed. One hundred and six patients met these criteria with a mean follow-up of 8.2 years (range, 1.0 to 18.8 years). The annual overall progression for the 106 patients was −0.26 diopters (SD ± 0.24). In the 54 patients who underwent surgical correction, the rate of progression was −0.25 diopters (SD ± 0.23) versus −0.27 (SD ± 0.25) in those who were merely observed (P = .59).

DISCUSSION

The findings from this population-based study of 135 children with intermittent exotropia (IXT) showed a significant trend toward myopia over time. The Kaplan-Meier rate of developing myopia in this population was 7.4% by 5 years of age, 46.5% by 10 years, and 91.1% by 20 years. Whether or not a patient underwent surgical correction did not appear to have an impact on his or her rate of myopic progression.

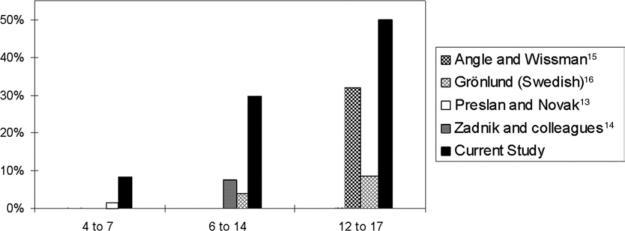

The initial refractive error of our population of children with intermittent exotropia is comparable to published reports of patients with IXT (Table 2). Kushner reported an average refractive error of plano for 62 exotropic children at a mean age of 4.4 years.11 Caltrider and Jampolsky reported a mean refractive error of −0.669 in 15 children at a mean age of 6.9 years.12 Although similar to reports in patients with IXT, the prevalence of myopia in our population was markedly higher than published reports of children surveyed in a general population (Table 3). In the United States, Preslan and Novak reported a myopia (≤−0.75 diopters) prevalence of 3.1% in their population of 4- to 7-year-olds residing in Baltimore, Maryland.13 Zadnik and associates, describing a population of 6- to 14-year-olds, found myopia (≤−0.75 diopters) in 7.5% of their patients.14 Angle and Wissmann reported that 31.8% of 12- to 17-year-olds examined by the U.S. National Health Survey were myopic (≤−1.0 diopters).15 As shown in Figure 4, our cohort of patients with intermittent exotropia had a far greater prevalence of myopia compared to similarly aged American children reported by these authors. Since the population in Olmsted County has a high rate of Scandinavian ancestry, we also included a Swedish population reported by Grön-lund and associates16 in Figure 4.

TABLE 2.

Published Reports of Mean Initial Refractive Error in Patients With Intermittent Exotropia

| Author(s) | Number of Patients | Mean Age at Initial Examination in Years | Mean Initial Horizontal Deviation in Prism Diopters | Mean Initial Refractive Error in Diopters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kushner11 | 62 | 4.4 | 28 | plano ± 1.40 |

| Caltrider and Jampolsky12 | 15 | 6.9 | Not specified | –0.669 (–3to + 1.75) |

| Current study | 135 | 5.6 | 21 | +0.26 (–7.75 to + 3.13) |

TABLE 3.

Published Reports of Myopia Prevalence in Cohorts of Children by Age Range

| Author(s) | Country of Study | Age Range in Years | Sample Size | % with Myopia | Kaplan-Meier Rate of Myopia Prevalence (%) in our Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preslan and Novak13 | United States | 4 to 7 | 680 | 3.1 | 8.8 |

| Zadnik and associates14 | United States | 6 to 14 | 716 | 7.5 | 43.0 |

| Grosvenor30 | Vanuatu | 6 to 19 | 788 | 2.9 | 57.3 |

| Cummings31 | United Kingdom | 8 to 10 | 1809 | 24.4 | 36.1 |

| Auzemery and associates32 | Madagascar | 8 to 14 | 1081 | 0.92 | 52.1 |

| Lin and associates33 | Taiwan | 13 to16 | 2353 | 49.6 | 72.5 |

| Angle and Wissmann15 | United States | 12 to 17 | 13 536 | 31.8 | 72.6 |

| Au Eong and associates34 | Singapore | 15 to 25 | 110 236 | 44.2 | 88.7 |

a The percentage presented was calculated based on the mean Kaplan-Meier rate for each age in the range specified.

FIGURE 4.

A comparison of the prevalence of myopia by age from this study with published reports of normal populations from the United States.

A number of factors have been associated with myopic progression, including ethnicity, birth during summer months, female gender, younger baseline age at onset, high IQ scores, prolonged study time, and parental myopia.17–22 Although we did not examine the IQ of study patients or the prevalence of parental myopia, two-thirds of the children in this study were female,23 which may partially explain the high rate of myopic progression. However, the birth months of our study patients were not significantly concentrated in the summer. The elevated risk associated with a younger age at baseline and Asian ethnicity were also not factors for our population. While it is well known that myopia is prevalent among Asian populations (Table 3), it is interesting to note that exotropia is also at least twice as common as esotropia in Asia,2,24 while the reverse is true for Western populations. However, it is unknown why the Caucasian children with IXT in this study, whose mean initial refractive error was hyperopic, developed myopia as fast as or faster than that described for Asian populations (Table 3).

There are several potential explanations for the association between IXT and myopia. A relationship between outdoor activity and less myopia coupled with increased myopia among children performing extended near work has recently been reported.19,20,25,26 It could be argued that children living in the colder climate of Minnesota are more likely to stay indoors performing near work, thereby enhancing their potential for developing myopia. However, this finding was not seen among children residing in the similarly cold climate of Sweden.16 Also, children with IXT are likely to have more frequent ophthalmic examinations, potentially leading to an earlier diagnosis and correction of myopia. This close observation and possible early correction may adversely alter emmetropization. The increased accommodative demand in children with intermittent exotropia may be another factor.27 Chua and associates have shown that the reduction of accommodation with atropine eye drops slowed the progression of moderate myopia and axial elongation in Asian children.28 However, additional investigations have shown an increase in progression of myopia after the discontinuation of atropine.29 Further study is needed to clarify the relationship between myopia, accommodation, and IXT. While we are unable to state that IXT causes myopia, they appear to be significantly linked and intermittent exotropia may be a risk factor for myopic progression.

There are a number of limitations to the findings in the current study. Its retrospective nature is limited by imprecise inclusion criteria and unequal follow-up. We attempted to overcome the latter weakness by employing the Kaplan-Meier method to estimate the rate of myopic progression. Second, not all refractions were performed with a cycloplegic agent. However, the mean age at the final refraction for the 135 study patients was 18 years, an age at which a cycloplegic refraction is uncommonly performed for patients with myopia. We also could not determine the precise age at myopia onset since patients would often have myopia of varying degrees on presentation. For these reasons, myopic progression was determined from the date at diagnosis rather than the age at onset, which is difficult to determine for any patient with refractive error. Moreover, although the study patients represent a population-based cohort, we were unable to identify a representative control group from the same population with which to compare our refractive error findings. Additionally, although the region is relatively isolated, some exotropic residents of Olmsted County may have sought care outside of the region, thereby potentially biasing the study population. Finally, the demographics of Olmsted County limit our ability to extrapolate the findings from this study beyond other semi-urban white populations of the United States.

This study provides population-based refractive error data on 135 children with intermittent exotropia diagnosed over a 20-year period. More than 90% of patients were calculated to become myopic by early adulthood, a rate that is much higher than the general U.S. population and nearly double that of the Asian communities in which myopia and exotropia are more prevalent. These findings, which require confirmation elsewhere, demonstrate an association between intermittent exotropia and myopia.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by an unrestricted grant from research to prevent blindness, Inc, New York, New York, and by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant #RO1-AR30582) through the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Bethesda, Maryland. Involved in design and conduct of the study (B.M., N.E.); preparation and review of the study (B.M., N.E.); data collection (N.E., K.N.); and statistical analysis (N.D.).

Institutional review board approval from the Mayo Clinic and the Olmstead Medical Group was obtained for this study.

Footnotes

The authors report no financial disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Govindan M, Mohney BG, Diehl NN, Burke JP. Incidence and types of childhood exotropia: a population-based study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chia A, Roy L, Seenyen L. Comitant horizontal strabismus: an Asian perspective. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1337–1340. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.116905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrahamsson M, Fabian G, Sjostrand J. Refraction changes in children developing convergent or divergent strabismus. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:723–727. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.12.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donders FC. On the anomalies of accommodation and refraction of the eye with a preliminary essay on physiological dioptrics. The New Sydenham Society; London: 1864. p. 292. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gwiazda J, Marsh-Tootle WL, Hyman L, Hussein M, Norton TT. Baseline refractive and ocular component measures of children enrolled in the correction of myopia evaluation trial (COMET). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:314–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ingram RM. Refraction as a basis for screening children for squint and amblyopia. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61:8–15. doi: 10.1136/bjo.61.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingram RM, Gill LE, Lambert TW. Emmetropisation in normal and strabismic children and the associated changes of anisometropia. Strabismus. 2003;11:71–84. doi: 10.1076/stra.11.2.71.15104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ip JM, Robaei D, Kifley A, Wang JJ, Rose KA, Mitchell P. Prevalence of hyperopia and associations with eye findings in 6- and 12-year-olds. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:678–685. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981;245:54–63. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1081-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan E, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kushner BJ. Does overcorrecting minus lens therapy for intermittent exotropia cause myopia? Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117:638–642. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.5.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caltrider N, Jampolsky A. Overcorrecting minus lens therapy for treatment of intermittent exotropia. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1160–1165. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(83)34412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Preslan MW, Novak A. Baltimore Vision Screening Project. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:105–109. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30753-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zadnik K, Satariano WA, Mutti DO, Sholtz RI, Adams AJ. The effect of parental history of myopia on children's eye size. JAMA. 1994;271:1323–1327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Angle J, Wissmann DA. The epidemiology of myopia. Am J Epidemiol. 1980;111:220–228. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grönlund MA, Andersson S, Aring E, Hard AL, Hellstrom A. Ophthalmological findings in a sample of Swedish children aged 4-15 years. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84:169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyman L, Gwiazda J, Hussein M, et al. Relationship of age, sex, and ethnicity with myopia progression and axial elon gation in the correction of myopia evaluation trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:977–987. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandel Y, Grotto I, El-Yaniv R, et al. Season of birth, natural light, and myopia. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Ip J, et al. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1279–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Smith W, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P, Saw SM. Myopia, lifestyle, and schooling in students of Chinese ethnicity in Singapore and Sydney. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:527–530. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.4.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saw SM, Katz J, Schein OD, Chew SJ, Chan TK. Epidemiology of myopia. Epidemiol Rev. 1996;18:175–187. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saw SM, Shankar A, Tan SB, et al. A cohort study of incident myopia in Singaporean children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:1839–1844. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nusz KJ, Mohney BG, Diehl NN. Female predominance in intermittent exotropia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:546–547. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambert SR. Are there more exotropes than esotropes in Hong Kong? Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:835–836. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.8.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dirani M, Tong L, Gazzard G, et al. Outdoor activity and myopia in Singapore teenage children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93:997–1000. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.150979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ip JM, Saw SM, Rose KA, et al. Role of near work in myopia: findings in a sample of Australian school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2903–2910. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh LA, Laroche GR, Tremblay F. The use of binocular visual acuity in the assessment of intermittent exotropia. J AAPOS. 2000;4:154–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chua WH, Balakrishnan V, Chan YH, et al. Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2285–2291. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tong L, Huang XL, Koh AL, Zhang X, Tan DT, Chua WH. Atropine for the treatment of childhood myopia: effect on myopia progression after cessation of atropine. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grosvenor T. Myopia in Melanesian school children in Vanuatu. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1988;185:24–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1988.tb02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cummings GE. Vision screening in junior schools. Public Health. 1996;110:369–372. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(96)80010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Auzemery A, Andriamanamihaja R, Boisier P. [A survey of the prevalence and causes of eye disorders in primary school children in Antananarivo]. Sante. 1995;5:163–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin LL, Hung PT, Ko LS, Hou PK. Study of myopia among aboriginal school children in Taiwan. Acta Ophthalmol Suppl. 1988;185:34–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1988.tb02658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Au Eong KG, Tay TH, Lim MK. Race, culture and myopia in 110,236 young Singaporean males. Singapore Med J. 1993;34:29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]