Abstract

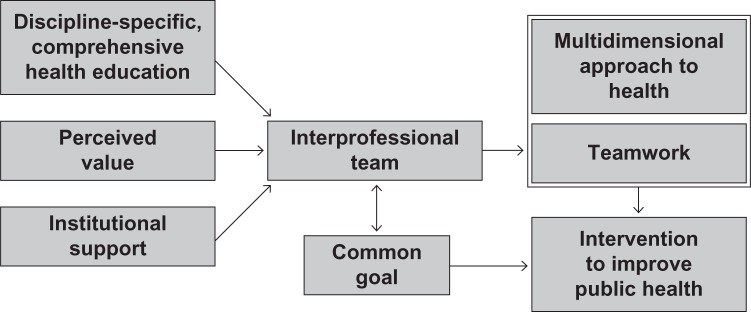

In the US, health care professionals are trained predominantly in uniprofessional settings independent of interprofessional education and collaboration. Yet, these professionals are tasked to work collaboratively as part of an interprofessional team in the practice environment to provide comprehensive care to complex patient populations. Although many advantages of interprofessional education have been cited in the literature, interprofessional education and collaboration present unique barriers that have challenged educators and practitioners for years. In spite of these impediments, one student-led organization has successfully implemented interprofessional education and cross-disciplinary collaboration. The purpose of this paper is to provide a conceptual framework for successful implementation of interprofessional education and collaboration for other student organizations, as well as for faculty and administrators. Each member of the interprofessional team brings discipline-specific expertise, allowing for a diverse team to attend to the multidimensional health needs of individual patients. The interprofessional team must organize around a common goal and work collaboratively to optimize patient outcomes. Successful interdisciplinary endeavors must address issues related to role clarity and skills regarding teamwork, communication, and conflict resolution. This conceptual framework can serve as a guide for student and health care organizations, in addition to academic institutions to produce health care professionals equipped with interdisciplinary teamwork skills to meet the changing health care demands of the 21st century.

Keywords: interprofessional education, conceptual framework, student organization, health care teams

Introduction

Health care professionals in the United States (US) are continuously challenged to provide comprehensive care to patient populations. Health is a multidimensional concept that encompasses biological, social, and psychologic dimensions,1 which are causally associated and ultimately impact quality of life.2 However, many individuals, clinicians included, have a tendency to see patients as dichotomously healthy or unhealthy,3 resulting in insufficient, noncomprehensive care. This rigid categorization creates deficiencies in the health infrastructure, which does not fully meet the dynamic health needs of the US population. Interprofessional education and collaboration can mitigate this deficiency, by offering health professional students the opportunity to engage with other students, expand individual concepts of health, and provide comprehensive team-based care. Interprofessional education occurs when students from two or more professions are given opportunities to learn about, from, and with each other and work towards enabling effective collaboration and improvement of health outcomes.4

In the US, health care professionals are overwhelmingly trained in uniprofessional settings, independent of interprofessional education and collaboration, leading to challenges in practice.5 This siloed approach to education produces health care professionals who lack interprofessional competence and role clarity, as well as crucial communication skills required to collaborate efficiently on a health care team.6 Health care partners often find that they merely work side by side, rather than efficiently as a team.7

Further, the composition of the health care team is often unclear, as demonstrated by the need for some professionals to declare their discipline as part of the interdisciplinary health care team in the academic literature.8,9 As a result, the health care system is decentralized, uncoordinated, and often lacks true collaboration.5 Ultimately, the patient suffers as individual health care professionals cannot meet the complex health care needs of the 21st century.10,11 Although the many benefits of interprofessional education have been demonstrated in the literature, implementation of interprofessional programs has been hindered due to unique barriers that have challenged educators and practitioners for years.

Barriers to interprofessional education and collaboration

The Institute of Medicine’s seminal 2003 report entitled “Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality” called for health care students and working professionals to collaborate on interdisciplinary teams and engage in quality improvement.12 Unfortunately, the US ranks near the bottom among developed nations in every quality parameter measure, thus heightening the growing importance of quality care and interprofessional teams. Furthermore, divisive battles among the health care disciplines have resulted in inhibited teamwork and collaboration by health care professionals.13 Kruse argues that health care professionals often lack respect for other professionals, fail to recognize the value of a team-based approach and a shared vision, and demonstrate a deficiency in communication skills that are required to set goals and priorities aimed to improve health care efficiency and effectiveness. These professional health care silos exist because we have allowed and fostered competitive training programs rather than cultivating an environment rich in collaboration, teamwork, and interprofessionalism.13

There are several key multilevel barriers that health professional schools face when proposing to implement interprofessional education, which include barriers set by administration, faculty members, and students.14 In a study by Curran et al researchers found that the main barriers to interprofessional education were scheduling, a rigid curriculum, battles over specialty areas, and lack of perceived value of such education,15 often resulting in incongruent attitudes and perceptions of administration, faculty, and students. Additionally, a lack of resources and institutional commitment have been shown to negatively impact interprofessional education endeavors.16

Barriers at the administrative level are multifactorial and include the potential resources needed for implementation.14 For example, administrators are challenged by space constraints, scheduling conflicts that arise with synchronizing courses, and requirements of numerous accreditation bodies. These barriers could require a modification of current physical structures, thus interprofessional education needs should be considered when new buildings and schools are constructed.

To optimize interprofessional education success, faculty members must fully appreciate the advantages of such programs and must personally engage to implement an interprofessional curriculum according to guidance set by their academic institution and the Institute of Medicine. Resistant faculty can create more barriers to change due to increased workload and lack of time for implementing interprofessional education within the curriculum.14

Finally, many health care settings have not yet fully implemented interprofessional care teams, thus creating a barrier for interprofessional education.14 Students may struggle with the application of an interprofessional care team or they may not perceive the value of working as an interprofessional care team in treating patients to increase quality of care.

Barriers stem from resistance to changes in academic, organizational, and professional culture. Unknown or unidentified barriers still exist, and administrators, faculty, and students must be prepared to overcome these barriers in order to develop into positively functioning interprofessional care teams focused on improving efficiency and quality of care.

Successful interprofessional extracurricular education and collaboration: student-led collaboration

In spite of the numerous barriers impeding the realization of interprofessional education, one student-led organization has successfully implemented interprofessional education and cross-disciplinary collaboration. The Inter Health Professionals Alliance (IHPA) at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) was officially organized in 2010 and offers interprofessional education and collaboration opportunities for emerging health professionals with the two-fold goal of improving the multidimensional health of underserved populations in the local community and improving interprofessional collaboration and education among health professional students.17 The purpose of this paper is to provide a conceptual framework for successful implementation of interprofessional education and collaboration for other student organizations, health care systems, and institutions guided by the experience of the IHPA. Figure 1 is a model for successful implementation and maintenance that can be replicated at any institution.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework

Prerequisites for interprofessional extracurricular education and collaboration

Knowledge and skill sets

Individual health professions are trained to possess unique knowledge and skill sets, and view health care with diverse perspectives. Professions interact with patients based on training, and each discipline has a tendency to focus on a different aspect of care. Health professional disciplines have a specific role to play in terms of patient care, and individuals enter their profession with a series of attitudes, beliefs, and understandings of what their role means to them.18 For example, hospital-based nurses are trained to have an ongoing and continual relationship with the patient, whereas hospital physicians attend to patients periodically.19 In this same setting, hospital social workers are involved in discharge planning, which includes coordinating community support systems and patient relocation to other medical facilities, and specialized patient and family instruction to perform post hospital care.20 As each of these components come together to form an interdisciplinary team, professional knowledge and skill sets have the ability to unify and meet all of the patient’s comprehensive health needs.

The IHPA consists of a diverse array of students, including baccalaureate, graduate, professional, and internship students from the schools of medicine, nursing, dentistry, pharmacy, social work, allied health and dietetics professions biomedical engineering internship programs hosted by the VCU health system. During health outreach events, each health profession contributes discipline specific knowledge, while recognizing shared knowledge and skills. For example, clinical students including those in nursing, medical, and pharmacy programs engage in blood pressure screenings, public health and social work students discuss community resources and nonclinical health-related issues, and dietetic interns provide healthy food tours of the grocery store where the health outreach programs are hosted.

Perceived value

When forming Interprofessional Education (IPE) teams, it is critically important to be aware of health professional students’ time constraints. Due to their limited time, it is essential that students place value on their interprofessional interactions and experiences. Perceived value, or task value, has been defined in several ways, including the importance of achieving a goal, the value of success, and broadly in terms of human values.21 Health professional students may value interprofessional education and collaboration as a tool for practicing professional socialization or as a means to improve role clarity and professional competence.22,23 Participation in interprofessional teams allows students to develop role clarity while students are still receiving their education, allowing a smooth transition to productive teamwork upon graduation, and further socializing them to their future careers. Students may enter health professional programs with perceived value of interprofessional learning, but university faculty and administration also have the unique opportunity to foster this value by leading through example and discussing the benefits incurred by the health professional and ultimately, the patient.

During initial planning and organization of the IHPA, students independently recognized the lack of interprofessional opportunities and worked together to provide an interprofessional experience for VCU health professional student colleagues. Since IHPA activities are extracurricular, students are not required to contribute to or attend the events or meetings. Rather, students value the added benefits of interprofessional teamwork and are willing to commit personal time to interdisciplinary efforts.

Institutional support

An educational environment that embraces interprofessional education and collaboration will encourage students to place perceived value on the efforts (time, money, and support). Institutions may provide evidence of their support in several ways, including institutional policies that develop meaningful interprofessional opportunities for students,24 and support faculty efforts to encourage this strategy. Faculty support is essential because it is their role to facilitate interprofessional interactions and to provide guidance and supervision.25 Institutional support demonstrates to health professional students that interprofessional education and collaboration endeavors are valuable and worth pursuing.

The IHPA has been incredibly fortunate to garner institutional support from VCU. Initially, the IHPA engaged with faculty known to support student efforts, and gradually they connected with a number of faculty champions from all member schools to develop a network of faculty support. Furthermore, faculty members have advocated on behalf of the IHPA to recognize the academic and greater Richmond community benefits of interprofessional collaboration. The process of garnering institutional support is slow and ongoing, because historical structures and policies often hinder change. However, VCU leaders and administration have committed to improving interprofessional education and collaboration, which offers an additional push for faculty support.

Interprofessional education and collaboration benefits

Multidimensional approach to health

While health is a multidimensional concept including biological, social, and psychologic aspects,1 individual health professionals are trained to focus on their area of expertise which likely does not transcend these three distinct components. Each member of the interprofessional team brings discipline-specific expertise, allowing for a diverse team to attend to the multidimensional health needs of individual patients. Each profession contributes unique knowledge and skills to the interprofessional team, while individual professions focus on specific dimensions of health,26,27 as defined by professional education, training, and culture. One health care profession alone cannot meet the complex public health needs of the 21st century.10,11

Interprofessional teamwork

Medical errors and negative health outcomes are often associated with communication failures of the health care team.28 Thus, the concepts of patient safety and communication29 have increased the emphasis and necessity for training future health professionals to work collaboratively in interprofessional teams.30,31 Successful interdisciplinary education must address role clarity and skills related to teamwork, communication, and conflict resolution. Health professional students should be prepared to analyze team failures through a team-based approach and allow opportunities to reflect on observed team interactions. Debriefing sessions structured around concepts of effective interprofessional teamwork would guide students to interpret the complexities of observed, comanaged, and collaborative care.

Interprofessional education and collaboration around a common goal

Success of interprofessional teams and IHPA organization is attributed to the focus on a common goal,32 which often revolves around optimizing patient outcomes. However, other goals also have the potential to lead to success if the team has agreed on the goal and all members work collaboratively toward goal achievement. If the team does not communicate and share a common goal, patient care will suffer as team members resort to working in silos and fail to provide comprehensive care. Therefore, it is critical for the interprofessional team to share a common goal in order to optimize quality and effectiveness of care.

The common goal of the IHPA is to provide health outreach events to underserved local communities as a forum for interprofessional care, and expand interprofessional education activities for health professional students. All IHPA activities revolve around this mission and continued improvements are always embraced as long as they work toward these goals. Each of the above-described benefits, ie, a multidimensional approach to health, improved teamwork, and motivation to achieve a common goal, have been experienced by IHPA members and volunteers. Student involvement in the IHPA also improves professional competency, role clarity, interprofessional networks, and an individual’s knowledge and skills.34

Discussion

Successful student-led interprofessional education and collaboration can be achieved for health professional students utilizing the framework constructed from the experience of the IHPA. As a result of the success of IHPA, the VCU-Inova Regional Medical Campus has followed this framework to develop an IHPA branch to serve the unique needs of VCU-Inova students. The previous literature demonstrates that students can address public health needs in an interprofessional environment,33 in addition to organizing successful health clinics.35 Yet, to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first model to equip students and academic institutions with a framework to combine interprofessional education and collaboration to address broad public health needs by a student-led organization. Nascent interprofessional student organizations should strive to meet the three prerequisites to optimize their probability of success.

Health care practitioners can also utilize this framework to collaborate with academic institutions to meet the public health needs of their patient populations in an interdisciplinary environment. These partnerships have the potential to improve public health and address social determinants of health utilizing a multidimensional approach to health care. Student-led organizations have been demonstrated to provide high-quality care as prescribed by national standards.36,37 With the support and guidance of academic institutions and community partnerships, motivated students can utilize their knowledge and skill sets to work on an interdisciplinary team to meet public health needs. In addition to the potential public health improvement, individual students can benefit from professional socialization, and improved role clarity and professional competence.23 Finally, to optimize resources and obtain the greatest return on investment, ongoing evaluation and assessment methods need to be considered as crucial tools to demonstrate organization success.

Conclusion

Overall, the success of the IHPA has been due to the conceptual framework that was developed to solicit, maintain, and interact as an interprofessional health care team to meet the needs of individual patients. This conceptual framework can serve as a guide for student and health care organizations, in addition to academic institutions to produce health care professionals equipped with interdisciplinary teamwork skills to meet the changing health care demands of the 21st century.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Wolinsky FD. The Sociology of Health: Principles, Practitioners, and Issues. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson IB, Cleary PD. Linking clinical variables with health-related quality of life. A conceptual model of patient outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barr DA. Health Disparities in the United States: Social Class, Race, Ethnicity, and Health. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Accessed September 22, 2013]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2010/WHO_HRH_HPN_10.3_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Interprofessional Education Collaborative . Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011. [Accessed September 22, 2013]. Available from: http://www.aacn.nche.edu/education-resources/ipecreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sargeant J, Loney E, Murphy G. Effective interprofessional teams: “Contact is not enough” to build a team. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(4):228–234. doi: 10.1002/chp.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siple J. Drug therapy and the interdisciplinary team: A clinical pharmacist’s perspective. Generations. 1994;18(2):49. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons K, Connolly RP, Bonifas R, et al. Psychosocial assessment of nursing home residents via MDS 3.0: Recommendations for social service training, staffing, and roles in interdisciplinary care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(2):190.e9–190.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mariano C. The case for interdisciplinary collaboration. Nurs Outlook. 1989;37(6):285–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis VA, Larson BK, McClurg AB, Boswell RG, Fisher ES. The promise and peril of accountable care for vulnerable populations: a framework for overcoming obstacles. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(8):1777–1785. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Institute of MedicineGreiner A, Knebel E, editors. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kruse J. Overcoming barriers to interprofessional education. Fam Med. 2012;44(8):586–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buring SM, Bhushan A, Broeseker A, et al. Interprofessional education: definitions, student competencies, and guidelines for implementation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(4):59. doi: 10.5688/aj730459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curran VR, Deacon DR, Fleet L. Academic administrators’ attitudes towards interprofessional education in Canadian schools of health professional education. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(S1):76–86. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner S, Chamberlin G, Heestand D, Stowe C. Interdisciplinary didactic instruction at academic health centers in the United States: attitudes and barriers. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2002;7(3):179–190. doi: 10.1023/a:1021144215376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.VanderWielen LM, Enurah AS, Osburn IF, Lacoe KN, Vanderbilt AA. The development of student-led interprofessional education and collaboration. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(5):422–443. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2013.790882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oandasan I, Reeves S. Key elements of interprofessional education. part 2: Factors, processes and outcomes. J Interprof Care. 2005;19(Suppl 1):39–48. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulhall A. Nursing, research, and the evidence. Evid Based Nurs. 1998;1(1):4–6. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Judd RG, Sheffield S. Hospital social work: contemporary roles and professional activities. Soc Work Health Care. 2010;49(9):856–871. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2010.499825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eccles J, O’Neill S, Wigfield A. Ability self-perceptions and subjective task values in adolescents and children. What do children need to flourish? J Pers Soc Psychol. 2005;3:237–249. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodehorst TK, Wilhelm SL, Jensen L. Use of interdisciplinary simulation to understand perceptions of team members’ roles. J Prof Nurs. 2005;21(3):159–166. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hallin K, Kiessling A, Waldner A, Henriksson P. Active interprofessional education in a patient based setting increases perceived collaborative and professional competence. Med Teach. 2009;31(2):151–157. doi: 10.1080/01421590802216258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell PH, Belza B, Schaad DC, et al. Working across the boundaries of health professions disciplines in education, research, and service: the University of Washington experience. Acad Med. 2006;81(10):891–896. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000238078.93713.a6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barnsteiner JH, Disch JM, Hall L, Mayer D, Moore SM. Promoting interprofessional education. Nurs Outlook. 2007;55(3):144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reed J, Watson D. The impact of the medical model on nursing practice and assessment. Int J Nurs Stud. 1994;31(1):57–66. doi: 10.1016/0020-7489(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones R, Bhanbhro SM, Grant R, Hood R. The definition and deployment of differential core professional competencies and characteristics in multiprofessional health and social care teams. J Prof Nurs. 2013;21(1):47–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brock D, Abu-Rish E, Chiu C, et al. Interprofessional education in team communication: working together to improve patient safety. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(5):414–423. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leonard M, Graham S, Bonacum D. The human factor: The critical importance of effective teamwork and communication in providing safe care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(Suppl 1):i85–i90. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyrkjebo JM, Brattebo G, Smith-Strom H. Improving patient safety by using interprofessional simulation training in health professional education. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(5):507–516. doi: 10.1080/13561820600918200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeSilets LD. The Institute of Medicine’s redesigning continuing education in the health professions. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2010;41(8):340–341. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20100726-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buljac-Samardzic M, Dekker-van Doorn CM, van Wijngaarden JDH, van Wijk KP. Interventions to improve team effectiveness: a systematic review. Health Policy. 2010;94(3):183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sheu LC, Toy BC, Kwahk E, Yu A, Adler J, Lai CJ. A model for interprofessional health disparities education: student-led curriculum on chronic hepatitis B infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(Suppl 2):S140–S145. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1234-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VanderWielen LM, Do EK, Diallo HI, LaCoe KN, Nguyen NL, Parikh SA, Rho HY, Enurah AS, Dumke EK, Dow AW. Interprofessional Collaboration Led by Health Professional Students: A Case Study of the Inter Health Professionals Alliance at Virginia Commonwealth University. Journal of Research in Interprofessional Practice and Education [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simpson SA, Long JA. Medical student-run health clinics: important contributors to patient care and medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):352–356. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0073-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryskina KL, Meah YS, Thomas DC. Quality of diabetes care at a student-run free clinic. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(4):969–981. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zucker J, Gillen J, Ackrivo J, Schroeder R, Keller S. Hypertension management in a student-run free clinic: meeting national standards? Acad Med. 2011;86(2):239–245. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820465e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]