Abstract

This case report depicts the clinical course of a female patient with unilateral retinitis pigmentosa (RP), who presented first in 1984 at the age of 43 years. At the beginning, there were cells in the vitreous leading to the diagnosis of uveitis with vasculitis. Within 30 years, the complete clinical manifestation of RP developed with bone spicule-shaped pigment deposits, pale optic disc, narrowed arterioles, cystoid macular oedema, posterior subcapsular cataract, concentric narrowing of the visual field and undetectable electroretinogram signal. At the age of 72 years, there are still no signs of retinal dystrophy in the other eye.

Background

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the most common retinal dystrophy affecting first the rods, and in more advanced stages, the cones, too (rod–cone dystrophy).1 It usually manifests within the first three decades with a bilateral, symmetric impairment of visual functions along with decrease of night vision and gradually concentric loss of peripheral vision. At fundoscopy, bone-spicule pigmentary changes are typical for the disease, but might be missing (RP sine pigmento). Further signs are pallor of the optic disc, arteriolar narrowing and atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Decrease of visual acuity occurs mainly in later stages of the disease, especially if cystoid macular oedema and subcapsular cataract develop. RP can occur sporadically or hereditary. The inheritance pattern can be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or X-chromosomal.1

Treatment options for RP are rare: systemic therapy with vitamin A has been proposed.2 However, it is controversial due to its side effects.

Case presentation

A 43-year-old female patient presented first in 1984 because of unilateral decrease of visual acuity. She reported that uveitis had been diagnosed 1 year ago. Medical history showed no systemic infections, rheumatic diseases or vasculitis. Family history was negative for hereditary ocular diseases.

Visual acuity was 16/20 at the first presentation in 1984 in the right eye. The anterior segment was without pathological findings, especially there were no signs of uveitis as retrocorneal precipitates, heterochromia and synechia. On fundus examination, vitreous cells and periphery pigment epithelium irregularities could be seen. The fundus changes were interpreted as vasculitis in uveitis of unknown origin.

At the follow-up examinations in 1988 and 1993, visual acuity was 24/20 and 20/20, respectively, in the right eye. The left eye was without pathological findings, visual acuity was 20/20.

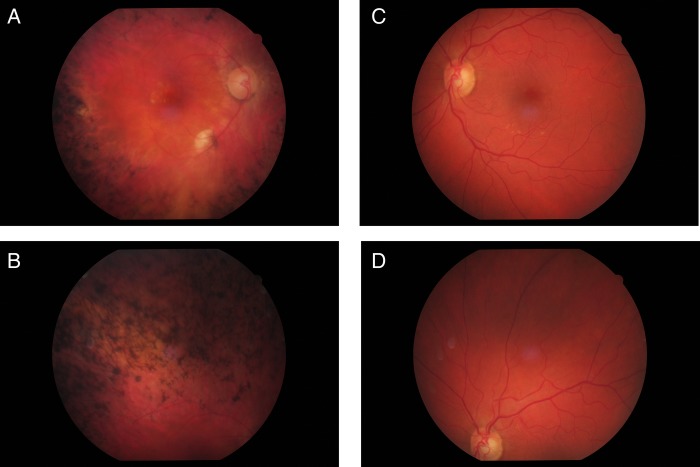

In 2008, the patient presented again with a progressive decrease in visual acuity to 1/20. The anterior segment was without pathological findings except for a beginning posterior subcapsular cataract. On fundus examination, a pale optic disc, narrowed arterioles and extensive proliferations of the pigment epithelium in form of bone spicules in the periphery could be seen. The bone spicules reached the vascular arcades sparing the macula (figure 1A,B). The left eye showed drusen of the macula and a large optic disc, but no signs of RP (figure 1C,D).

Figure 1.

Photography of fundus of both eyes (2013). (A) Central fundus of the right eye: pale optic disc, narrow arterioles, bone-spicule pigmentary changes reaching to the vascular arcade and pigmentary irregularities of the macula. (B) Upper middle periphery of the right eye: extensive bone-spicule pigmentary changes. (C) Central fundus of the left eye: large optic disc and drusen of the macula. (D) Upper middle periphery of the left eye: retina without signs of beginning retinitis pigmentosa.

The changes in the macula of the right eye (RPE irregularities, focal RPE atrophy at the inferior vascular arcade) might be consistent with the beginning age-related macular degeneration.

In 2013, a cystoid macular oedema had been diagnosed in the right eye. Visual acuity was 3/20. The patient reported ‘shifting of the image’ with transient binocular double vision. This might be explained by impairment of fusion due to the advanced, unilateral, concentric narrowing of the visual field in the right eye.

Treatment

In our patient, the RP was strictly unilateral. There are no studies showing a benefit of vitamin A in unilateral RP. Therefore, we did not recommend this treatment to our patient.

In 2012, cataract surgery with phacoemulsification and implantation of an intraocular lens was performed. Surgery was uneventful; visual acuity increased from 1/20 to 8/20.

For cystoid macular oedema, different therapeutic options exist, for example, topical or systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors,3 4 intravitreal vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors and steroids. Our patient reported fusion deficiency due to advanced visual field loss. Therefore, we did not try to improve visual acuity by treating the macular oedema, in the belief that the right eye is going to be ‘faded out’ by cortical functions.

Differential diagnosis

The diagnosis is unilateral RP. The differential diagnosis includes the following so-called phenocopies, that is, retinal disorders mimicking RP:

Ocular infections: syphilis, rubella

Congenital infections with rubella virus or treponema pallidum can lead to retinal changes with pigment irregularities, decrease in visual acuity and narrowing of the visual field. Thereby, they can resemble RP. They can occur unilaterally or bilaterally, usually early in life. A concentric narrowing to the central 5° as in RP is not typical for infectious retinopathies; the prognosis is better than in RP.

Electroretinogram (ERG) might help to distinguish between RP and infectious retinopathies: while in RP, the b-wave latency as well as the amplitudes are pathological, in syphilitic retinopathy, only the amplitudes are reduced whereas the latencies remain normal. Although ERG responses are reduced in infectious retinopathies, they are usually not completely extinguished/non-recordable as in RP.5–7

Toxic retinopathies

Intake of antipsychotics of the group of phenothiazines can induce not only a maculopathy, but also a peripheral pigmentary retinopathy. Its clinical signs and symptoms (eg, decreased night vision) can appear as in RP. Since our patient had no history of psychiatric diseases or intake of antipsychotics, this differential diagnosis could be excluded.8

Traumatic retinopathies

After a blunt trauma, pigmentary changes resembling RP have been described. RPE cells migrate into the retina and form bone-spicule formations as in RP. Traumatic retinopathies can be excluded by a detailed medical history. Furthermore, traumatic retinopathies usually do not progress in the same way as RP.9

Carcinoma-associated retinopathy/autoimmune retinopathy

In some patients with cancer, antibodies against retinal antigens (eg, antirecoverin antibodies) develop, leading to a paraneoplastic syndrome called carcinoma-associated retinopathy or autoimmune retinopathy. It manifests in the same manner as RP with decrease of visual acuity, ring-shaped or concentric scotoma and narrowed retinal arterioles. Since the autoantibodies circulate in the blood stream, usually both eyes are affected. ERG amplitudes are reduced, but the degree of amplitude reduction is less severe than in RP. In contrast to RP, where scotopic amplitudes are affected earlier than photopic amplitudes, in autoimmune retinopathy, scotopic and photopic ERG results are reduced equally.10–12

The exclusion of phenocopies is important if the clinical appearance of RP is not typical, for example, missing bone spicules. In our patient, medical history showed no carcinoma, trauma or long-term systemic medication with ocular side effects.

Investigations

Laboratory

At first presentation in 1984, an investigation regarding systemic diseases was made revealing no pathological findings (human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B-27 positive, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 12/25 mm, antinuclear antibodies 1/20, normal blood count, no antibodies against DNA, rheumatoid factor, streptococcus and cryoglobulins).

Molecular genetic analysis

Molecular genetic tests were performed in 2002, but showed no specific mutation. Pedigree analysis and screening of the two daughters of the patient for retinal signs of RP raised no suspicion for hereditary RP.

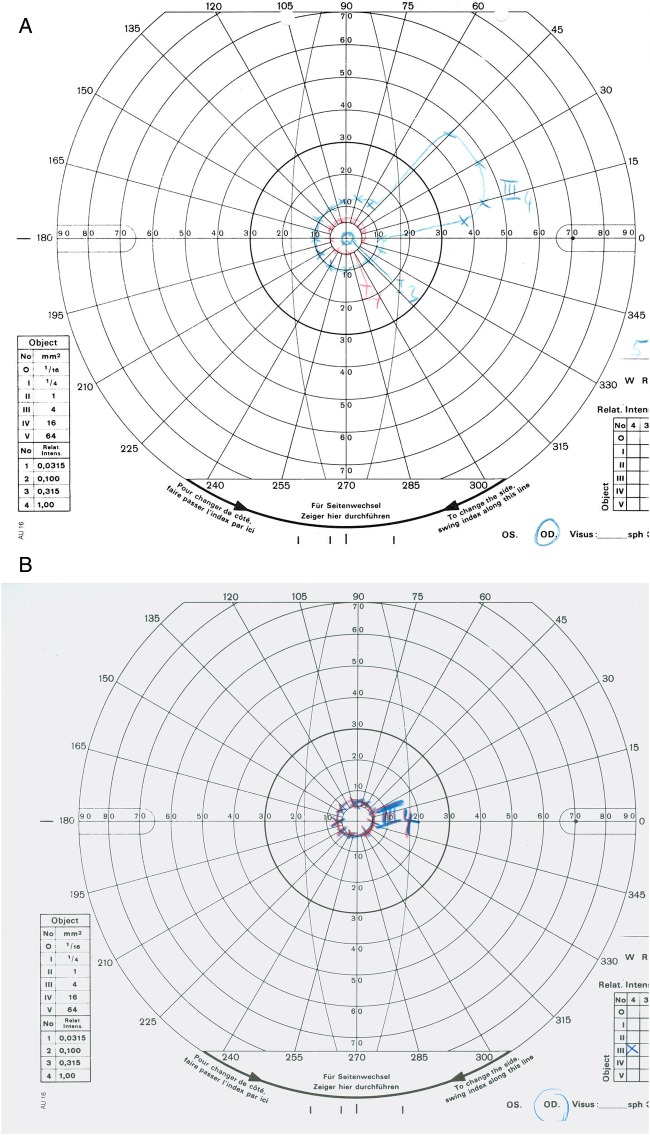

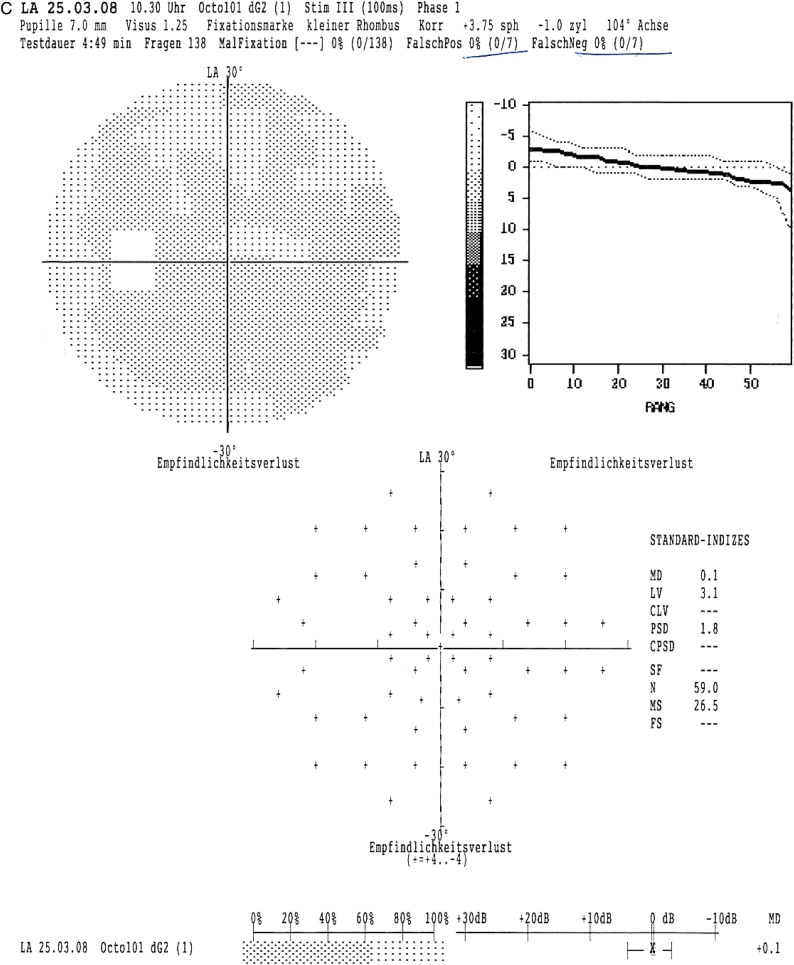

Visual field analysis (kinetic perimetry)

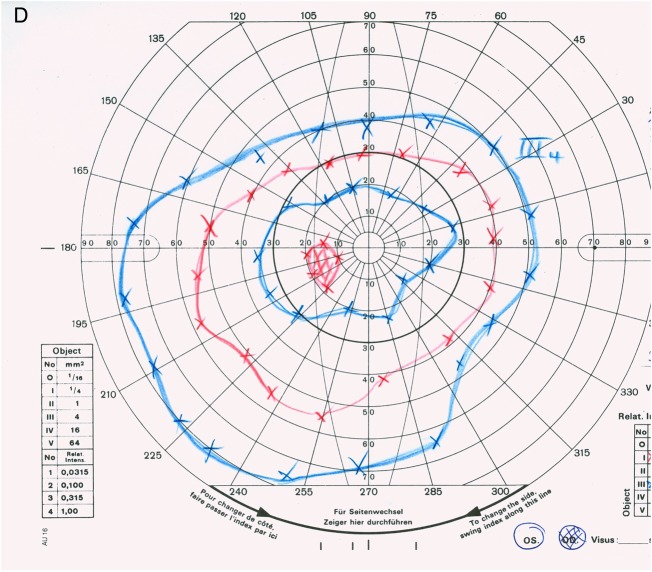

Visual field testing revealed normal visual fields in both eyes in 1988. In 2008, kinetic perimetry of the right eye showed a concentric narrowing of the visual field with a maintained sectorial area in the nasal superior visual field (figure 2A). A progressing concentric narrowing of the visual field to the central 5° could be detected in the right eye in 2013 (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Visual fields from 2008 and 2013. (A) Right eye (2008): concentric narrowing of the visual field with maintained sectorial area. (B) Right eye (2013): progressive concentric narrowing of the visual field to the central 5°. (C) Left eye (2008): regular 30° visual field (static perimetry). (D) Left eye (2013): regular outer borders of the visual field (kinetic perimetry).

In the left eye, a static perimetry was performed in 2008 to exclude glaucoma in a large optic disc (figure 2C). In 2013, kinetic perimetry showed no focal scotoma or concentric narrowing of the visual field (figure 2D).

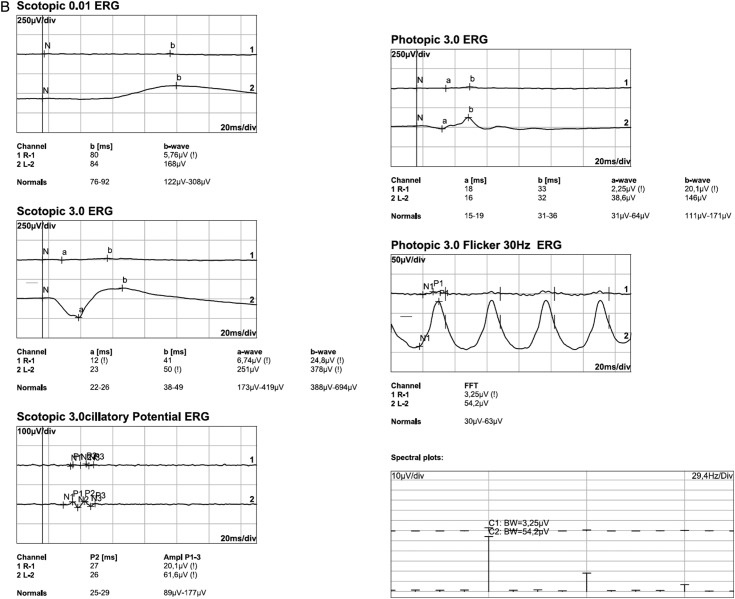

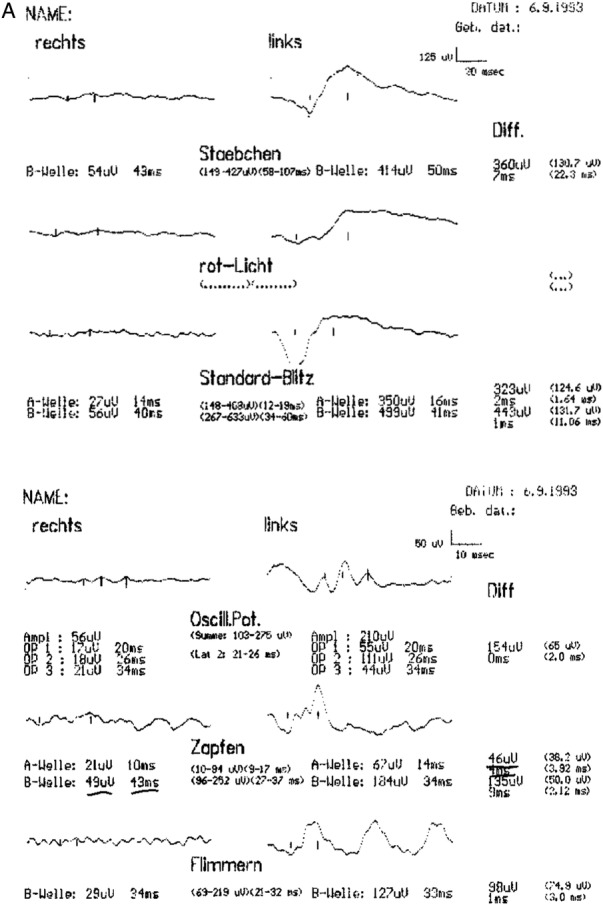

Electrophysiology

The scotopic and photopic flash ERG showed nearly extinguished reponses in the right eye, but regular answers with normal amplitudes in the left eye in 1993 (figure 3A). In 2013, the flash ERG (performed by International Society for Clinical Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) standards) was repeated and the findings were confirmed (figure 3B). ERG responses were now completely extinguished in the right eye with normal responses in the left eye. The electro-oculogram was normal in the unaffected left eye, but had a diminished basis potential with an absence of the light peak in the right eye (2013).

Figure 3.

Flash electroretinogram (ERG) from 1993 and 2013. (A) Right/left eye (1993): reduced scotopic (Stäbchen) and photopic (Zapfen) ERG responses in the right eye (Rechts), normal ERG responses in the left eye (Links). (B) Right eye (2013): extinguished scotopic and photopic ERG responses; left eye (2013): regular responses with normal amplitudes in the scotopic and photopic ERG.

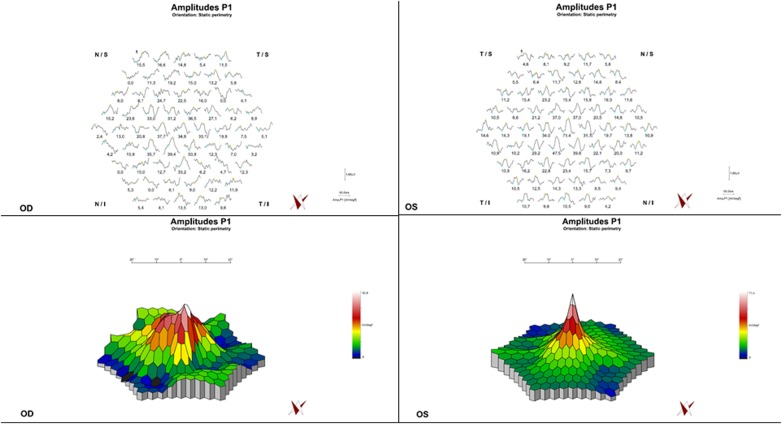

In multifocal ERG, a decrease of the amplitudes could be recorded in the right eye from the periphery to the centre (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Multifocal electroretinogram (ERG; 2013). Right eye: decreased responses and abnormal configuration of potentials involving the fovea; left eye: regular ERG responses.

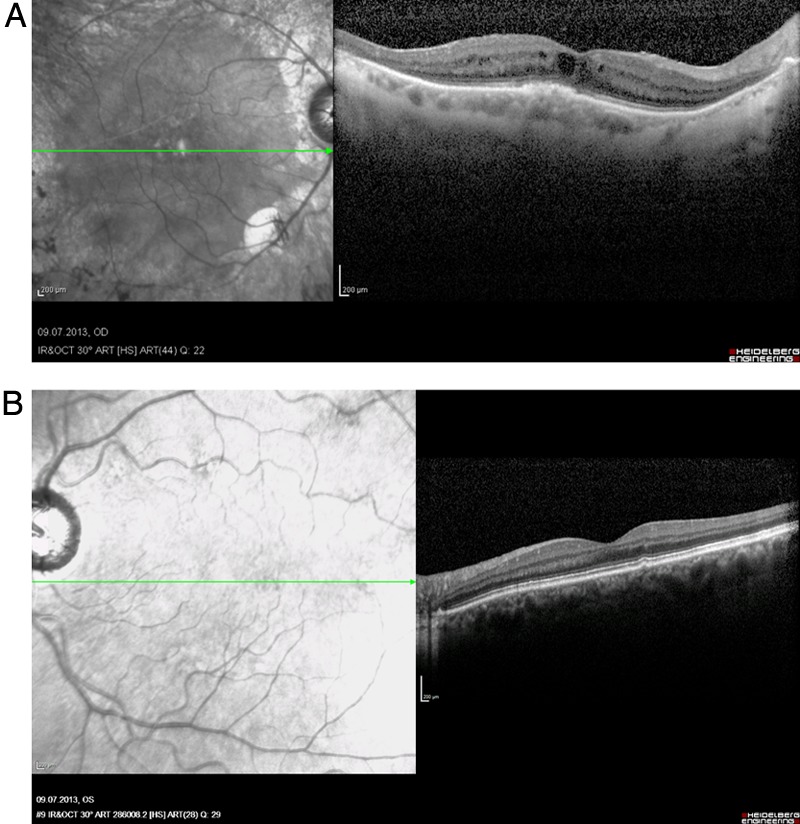

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography

Spectral domain Spectral domain optical coherence tomography examination (Spectralis, Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Deutschland, Germany) showed a cystoid macular oedema in the right eye at the recent presentation in July 2013 (figure 5A). The OCT scan of the left eye revealed a regular retinal structure apart from a single drusen formation (figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Spectral-domain optical coherence tomography of the macula (right eye, 2013). (A) Right eye: cystoid oedema of the macula and atrophy of the inner retinal layers in the peripheral macula. (B) Left eye: single, parafoveal drusen formation, otherwise normal retinal structure.

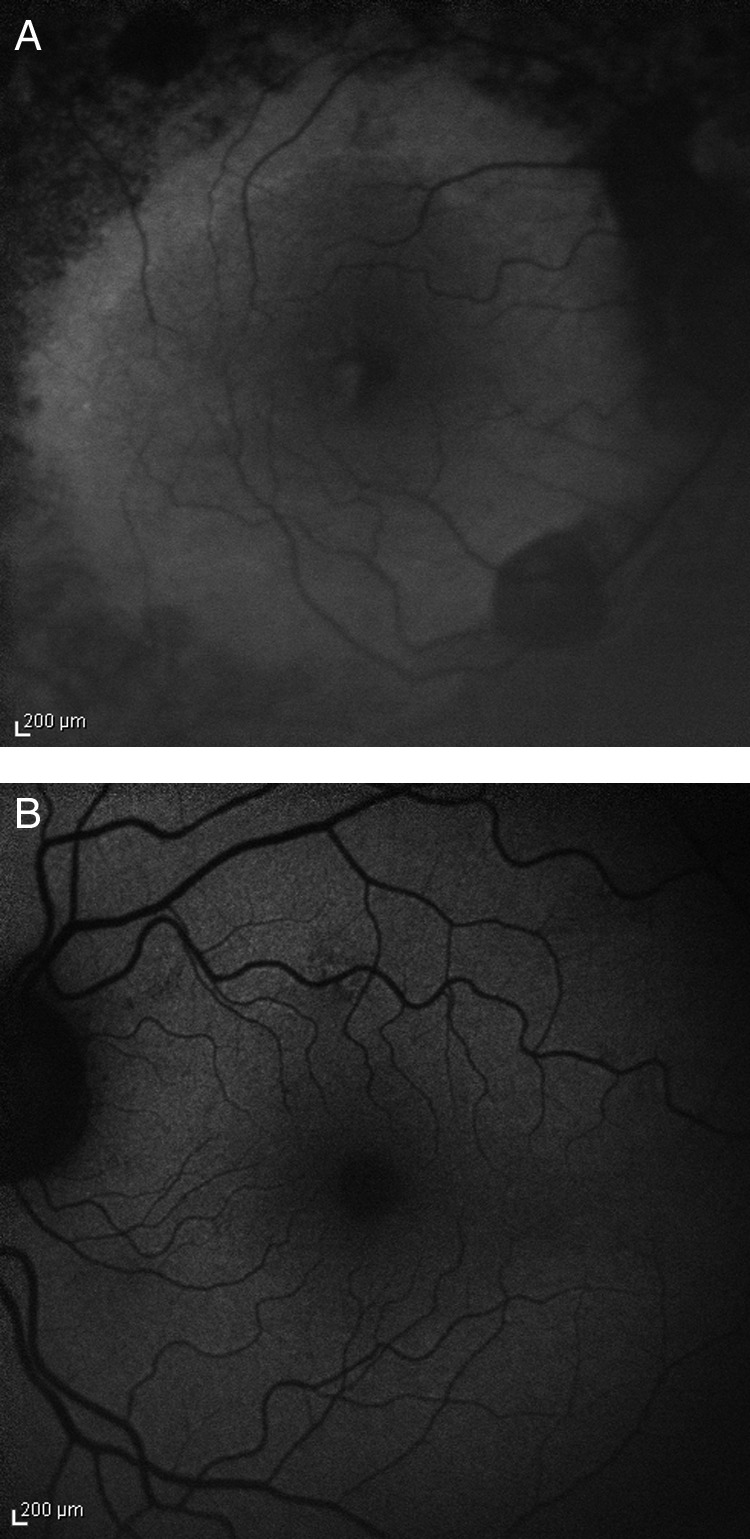

Fundus autofluorescence

Fundus autofluorescence was reduced in the affected areas of the right eye, consistent with a chorioretinal atrophy and shadowing by the diffuse bone-spicule bodies.

In the left eye, irregularities of fundus autofluorescence in the macula could be detected which correlate with drusen and pigmentary changes (figure 6).

Figure 6.

Fundus autofluorescence. (A) Right eye: decreased autofluorescence in the affected areas of the retina, consistent with chorioretinal atrophy and shadowing by proliferations of the pigment epithelium. (B) Left eye: irregularities of the fundus autofluorescence due to pigmentary changes and drusen of the macula.

Outcome and follow-up

Visual acuity of the right eye was 3/20 at the recent follow-up. The patient copes well with the disease because the left eye has full function without signs of beginning RP.

Discussion

Unilateral RP is a rare manifestation form of rod–cone dystrophy, which was first described in 1948.13 Since retinal dystrophies are usually bilateral due to their genetic background, a unilateral manifestation requires an explanation: one pathomechanism is the occurrence of genetic mosaics, that is, the mutation affects only some of the cells, and the second mechanism is a somatic mutation instead of a germline mutation.14

Marsiglia et al examined five patients with unilateral RP and found a USH2AW4149R mutation in one of the patients. Because of the heterogeneity of RP in general, the detection of the inheritance pattern is not always successful also in bilateral cases. Therefore, it is unknown whether the other four patients of this study had no genetic disposition for RP or whether the detection of the mutation was unsuccessful because the specific mutation has not been described yet.14

In another case report, a p.R677X germline mutation in the RP1 gene has been found in a patient with unilateral RP and a positive family history with another ten bilaterally affected relatives.15

Francois and colleagues16 defined the criteria for the diagnosis of unilateral RP: (1) occurrence of typical findings of RP in one eye, (2) normal fundus and normal full-field ERG in the healthy eye, (3) exclusion of infectious, inflammatory and vascular reasons for RP-like fundus changes.

Potsidis et al17 analysed the clinical course of 15 patients with unilateral RP in a recent study. They found an annual decrease of the visual field area of 4.7% and of the amplitude in the scotopic ERG of 4.6%. In older patients, the decrease of visual acuity was faster than in younger patients.

Farrell18 found a rate of unilateral RP of 5% in their study population. This rate is quite high compared with the single case reports in the literature. One explanation, which the authors give themselves, might be that the study population was obtained from a tertiary referral centre for retinal dystrophies with a bias towards rare cases. Patients with unilateral RP showed a significantly later manifestation of RP. However, this might be because the patients become symptomatic later since the visual function in the unaffected eye compensates for the deficiencies of the other eye. Therefore, the patients possibly present at an ophthalmologist in later stages of the disease compared with patients with bilateral RP. Among the 14 patients who were examined in this study, 5 patients had a positive family history. However, the relatives of these patients had a classical bilateral affection.

The differential diagnosis of unilateral RP includes the so-called phenocopies, that is, diseases which mimic the clinical appearance of RP. In our patient, there were only vitreous cells and slight pigmentary changes at the beginning, leading to the misdiagnosis of uveitis. The nearly extinguished ERG in 1993 indicated RP, although the fundus appearance did not show the classical signs of RP.

When the patient presented again in 2008 and the following years, the typical signs of RP could be seen: bone-spicule pigmentary changes, pallor of the optic disc, narrowed arterioles, vitreous cells, cystoid oedema, posterior subcapsular cataract, concentric narrowing of the visual field and extinguished flash ERG. The serological exclusion of rubella infection is difficult 30 years after the first manifestation of the disease because it cannot be differentiated between a rubella infection and vaccination against rubella virus. Furthermore, it is not possible to say whether a rubella infection was really causative for the retinal changes or just an additional finding. Therefore, the serological results are only of interest in newly diagnosed retinal pigmentary changes.

Pigmentary changes of the retina can also occur in the context of an inflammatory eye disease, that is, uveitis or autoimmune diseases.10 Since there were no other signs for uveitis in our patient (no precipitates, cells in the anterior chamber, synechia, etc), it seems to be unlikely that a non-recurring mild iridocyclitis has provoked a tapetoretinal degeneration leading to blindness. We assume that the vitreous cells, which preceded the fundus changes in our patient, led to the misdiagnosis of uveitis.

The vitreous cells as the only initial finding in the affected eye and the unilaterality even after 30 years might be helpful information obtained from this case report for the clinical management of unilateral RP.

Learning points.

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) can be unilateral in rare cases.

Phenocopies which mimic the clinical appearance of RP should be excluded in these patients.

Unilaterality of RP can be explained by genetic mosaics or somatic mutations.

Footnotes

Contributors: JMW, GM and AGJ treated the patient as clinicians. JMW wrote the manuscript. GM and AGJ revised the manuscript thoroughly.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed

References

- 1.Hartong DT, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Retinitis pigmentosa. Lancet 2006;368:1795–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berson EL, Rosner B, Sandberg MA, et al. A randomized trial of vitamin A and vitamin E supplementation for retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111:761–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fishman GA, Gilbert LD, Fiscella RG, et al. Acetazolamide for treatment of chronic macular edema in retinitis pigmentosa. Arch Ophthalmol 1989;107:1445–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grover S, Apushkin MA, Fishman GA. Topical dorzolamide for the treatment of cystoid macular edema in patients with retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol 2006;141:850–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khurana R, Sadda S. Salt-and-pepper retinopathy of rubella. N Engl J Med 2006;355:499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Damasceno N, Damasceno E, Souza E. Acquired unilateral rubella retinopathy in adult. Clin Ophthalmol 2011;5:3–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lotery AJ, McBride MO, Larkin C, et al. Pseudoretinitis pigmentosa due to sub-optimal treatment of neurosyphilis. Eye (Lond) 1996;10:759–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam RW, Remick RA. Pigmentary retinopathy associated with low-dose thioridazine treatment. Can Med Assoc J 1985;132:737. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastek JV, Foos RY, Heckenlively J. Traumatic pigmentary retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol 1981;92:621–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lima LH, Greenberg JP, Greenstein VC, et al. Hyperautofluorescent ring in autoimmune retinopathy. Retina 2012;32:1385–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makiyama Y, Kikuchi T, Otani A, et al. Clinical and immunological characterization of paraneoplastic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54:5424–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ohguro H, Nakazawa M. Pathological roles of recoverin in cancer-associated retinopathy. Adv Exp Med Biol 2002;514:109–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreisler KK. Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa: two cases. Acta Ophthalmol 1948;26:385–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marsiglia M, Duncker T, Peiretti E, et al. Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa: a proposal of genetic pathogenic mechanisms. Eur J Ophthalmol 2012; 22:654–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukhopadhyay R, Holder GE, Moore AT, et al. Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa occurring in an individual with a germline mutation in the RP1 gene. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:954–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franceschetti A, Francois J, Babel J, et al. Chorioretinal heredodegenerations: an updated report of La Société d'ophthalmologie. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1974:266–74 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potsidis E, Berson EL, Sandberg MA. Disease course of patients with unilateral pigmentary retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011;52:9244–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell DF. Unilateral retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod dystrophy. Clin Ophthalmol 2009;3:263–70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]