Abstract

Development of next-generation sequencing, coupled with the advancement of computational methods, has allowed researchers to access the transcriptomes of recalcitrant genomes such as those of medicinal plant species. Through the sequencing of even a few cDNA libraries, a broad representation of the transcriptome of any medicinal plant species can be obtained, providing a robust resource for gene discovery and downstream biochemical pathway discovery. When coupled to estimation of expression abundances in specific tissues from a developmental series, biotic stress, abiotic stress, or elicitor challenge, informative coexpression and differential expression estimates on a whole transcriptome level can be obtained to identify candidates for function discovery.

Keywords: transcriptome, expression abundance, annotation, isoforms

1. INTRODUCTION

The genomes of some plant species remain one of the final frontiers in genomics due to technical challenges in obtaining quality sequences of the genomes of polyploid, highly repetitive, and heterozygous species. For example, the genome of bread wheat, a hexaploid, is estimated at 16 Gb (Arumuganathan and Earle 1991) and is composed of > 85% repetitive sequences (Paux et al. 2006). Thus, while next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms (Shendure and Ji 2008) can readily generate sequences for large repetitive polyploid genomes, assembly and reconstitution of the 21 chromosomes in bread wheat using whole-genome shotgun sequencing is not feasible with current sequencing and computational methods. For other species, the high degree of heterozygosity presents a barrier to robust assembly of the gene space because of uneven degrees of similarity among the haplotypes, even in a diploid genome (The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium 2011). Multiple approaches can be employed to overcome these technical barriers and obtain the genome sequences of these recalcitrant species. These include reducing the inherent heterozygosity by inbreeding for several generations (Jaillon et al. 2007), sequencing a progenitor species of the polyploid (Shulaev et al. 2011), generation of unique genetic material with reduced genome complexity (The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium 2011), and physical separation of chromosomes and targeted sequencing of a single or a few chromosomes (Paux et al. 2008). All these efforts require considerable investment in germplasm, genetic, genomic, or molecular resources and are generally only feasible in species with deep knowledge and access to germplasm, genetic resources, and reproductive biology and in which there is a scientific community well vested in obtaining the genome sequence. However, for species with limited germplasm, knowledge, funding, or community resources, development of alternative germplasm or genomic resources is impractical. A robust, inexpensive and rapid method for researchers to access the gene space of recalcitrant plant genomes is that of transcriptome sequencing, termed RNA-sequencing or RNA-seq (Wang et al. 2009).

De novo sequencing and assembly of transcriptomes has advanced substantially since the first publication of Expressed Sequence Tags (ESTs) in 1993, which were single-pass reads of cDNA clones (Adams et al. 1993). Because of improvements in sequencing technology from Sanger platforms to high-throughput massively parallel sequencing platforms such as Roche/454 (Margulies et al. 2005), Illumina (Bentley et al. 2008), and SoLiD™ (McKernan et al. 2009), coupled with the development of efficient, robust transcript assembly algorithms (Schulz et al. 2012; Robertson et al. 2010), researchers can now readily access the breadth, depth, and expression abundances of a transcriptome from any tissue(s) of any organism with relative ease and low cost. For medicinal plant species, often there is limited knowledge of the underlying genome with respect to size, ploidy, heterozygosity, and repetitive sequence content. Further, medicinal plant species are often from taxonomic groups lacking a quality reference genome from even a single species, further limiting estimations of genome structure and content. Finally, medicinal plant research communities are limited in size and typically are highly focused on biochemical pathways and/or on downstream pharmacological properties in animal and human systems. Thus, medicinal plant species that lack the appropriate resources for robust genome sequencing are prime targets for de novo transcriptome sequencing and assembly which can be coupled expression abundance estimates to reveal critical genes involved in biochemical pathways of interest. This chapter describes sample selection and preparation, sequencing recommendations, assembly methods, and annotation methods for de novo assembly and annotation of plant transcriptomes.

2. PLANT MATERIAL SELECTION AND QUALITY

2.1 Germplasm selection

To optimize assembly and data interpretation, RNA should be obtained from a single, established genotype if at all possible. If a population is to be sampled, the initial de novo assembly of the transcriptome should be made from sequences from a single individual if at all possible, which, in most cases, will not interfere with transcript abundance estimates from other individuals within the population.

2.2 Plant health

The extracted RNA and transcript sequences from infected plant material will reflect the extent of bacterial, fungal and insect contamination as computational approaches are limited in their ability to remove contaminating transcripts from the final assembly. Thus, any plant material to be used for RNA isolation should be free of microbial, insect, and other contaminating organisms. A special emphasis should be placed on growing plants in pasteurized or sterile soil media to reduce the contamination of RNA with fungal and oomycete pathogens. Plants should be visually inspected for insects and chemical control efforts utilized to eliminate or minimize infestation of aerial plant tissues by insects.

2.3 Tissue selection

For a robust de novo assembly, 4–5 diverse tissues that provide a broad representation of plant tissues and the underlying transcriptome should be selected for sequencing (e.g. roots, leaves, flowers, callus, fruit). These are referred to as the core tissues/libraries.

The core tissues should be augmented with multiple tissues/organs or treatments that reflect a range of conditions in which the metabolite of interest is present at variable levels (including absent) to provide contrasting conditions for coexpression analyses with transcripts and metabolites.

3. ISOLATION OF RNA

Excise tissue samples of interest, weigh, snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen and place at −80°C until RNA extraction. Once excised, tissue should be handled rapidly and placed into liquid nitrogen to limit degradation of the RNA.

Grind 1–5 gm of the plant tissue into a fine powder in liquid nitrogen using mortars and pestles precooled with liquid nitrogen. Place in a sterile plastic 50-ml tube cooled with liquid nitrogen and return to the −80°C freezer until processing further. Only one sample should be processed at a time and every precaution should be taken to keep samples from thawing.

Total RNA can be routinely isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy Plant RNA isolation kit (Catalog # 74903, Qiagen, Valencia, CA). However, for recalcitrant tissues (tissues yielding low levels of RNA or yielding RNA contaminated by carbohydrates or phenolics as evident by aberrant spectrophotometric ratios [ABS 260nm/280nm <1.7 or >1.85; ABS 300/260 >0.1]) the Spectrum Plant Total RNA isolation kit (Catalog # STRN10) from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) is recommended. When the Spectrum isolation kit is used, volumes of reagents should be according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and include all the precautions noted below.

Efforts should be taken to minimize nucleases at all steps of the procedure by wearing gloves and using RNAase-free plastic ware. Mortars and pestles should be thoroughly washed, sprayed with RNAse ZAP (Catalog # AM9780, Ambion/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), incubated 10 minutes at room temperature, rewashed, then dried at room temperature or in a drying oven; if not used immediately, mortars and pestles should be stored wrapped in aluminum foil.

For RNA extraction using the Qiagen RNAeasy Plant RNA kit, retrieve a plant sample from the −80°C freezer in a liquid nitrogen bath and weigh up to 100 mg (maximum) into a pre-chilled weigh boat. Transfer the sample to a pre-chilled 2.0-ml microcentrifuge tube, immediately add 450 µl of RLT buffer containing 4.5 µl of β-mercaptoethanol and vortex vigorously for 1 min according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Place the sample in a pre-heated 56°C heat block for 3 min to aid tissue disruption. Centrifuge for 3 min at >10,000 × g, transfer the lysate to a QIAshredder spin column and centrifuge for 2 min at >10,000 × g. Add one-half volume of 100% ethanol to the filtrate, mix by inverting, transfer to an RNeasy spin column, then centrifuge at >10,000 × g for 15 sec. Discard the filtrate and add 80 µl of DNase I solution directly to the RNeasy membrane column. Prepare the DNase I solution by gently mixing 10 µl of DNase I (RNase-free DNase, Catalog # 79254, Qiagen, Valencia, CA) with 70 µl of RDD buffer provided in the Qiagen RNeasy RNA isolation kit. Incubate the column at room temperature for 15 min before adding 350 µl of RW1 buffer (also provided in the kit), centrifuge for 15 sec at >10,000 × g and discard the filtrate. Wash the column twice with 500 µl of the RPE buffer provided in the kit, and centrifuge for 15 sec at >10,000 × g. Finally, elute the RNA from the column by adding 50 µl of RNase-free water, incubating for 10 min at room temperature, then centrifuging at >10,000 × g for 1 min. A second water elution should be performed to qualify the completeness of the first elution as determined by spectrophotometric assessment.

RNA yields should be calculated from absorbance readings at 260 nm using a conventional or Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) spectrophotometer (Abs260 1.0 = 44 µg/ml). Quality should be assessed by the absorbance 260/280 ratio (≥1.7), 300/260 (≤0.1) and evaluation by electrophoretic separation with an Agilent 2100 BioAnalyzer (RIN values ≥ 8.0) or equivalent.

4. GENERATION OF NEXT-GENERATION WHOLE TRANSCRIPTOME SEQUENCES

In this step, two types of libraries will be constructed and sequenced. The core library will contain RNA from multiple tissues, sequenced in the paired end (PE) mode, and used to generate the initial de novo assembly. Additional libraries need to be constructed from single tissues/treatments and sequenced in the singe end (SE) mode for transcript abundance estimates.

4.1 Removal of contaminating DNA in the RNA samples

Prior to library production, contaminating DNA should be removed from the RNA samples.

The TURBO DNA-free kit (Catalog # AM1907, Ambion/Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) can be used to remove DNA from 12–15 µg of RNA in a 50-µl sample.

RNA should be checked again for quantity and quality using the same methods as for RNA isolated described above

4.2 Construction of cDNA libraries for next-generation sequencing

-

Pooling RNA from multiple samples.

Typically, RNAs from as divergent tissues as possible (e.g., root, leaf, flower, stem, callus, fruit or seedlings) will provide the broadest representation of the transcriptome. For optimal assembly of a reference transcriptome, PE sequences greatly enhance the quality of the assembly. For the reference transcriptome, individual libraries should be made from the core tissues. Alternatively, RNA from multiple core tissues can be pooled and sequenced as a single library. For pooling, equal quantities of TURBO DNA-free RNA isolated from multiple tissues, from a single individual plant if possible, should be pooled to provide at least 20 µg of total RNA for library production. The advantage of keeping the core tissue libraries separate is that the reads from each library can also be used for expression abundance estimates, whereas once the RNA samples are mixed, expression abundances are uninformative.

For non-core tissues, libraries should be made from single tissues/treatments and sequenced from a single end.

-

cDNA library construction

cDNA libraries for sequencing on the Illumina platform should be made using the TruSeq RNA Sample Preparation kit (e.g., Catalog # RS-122-2001 (Set A) or RS-122-2002 (Set B), Illumina, San Diego, CA).

4.3 Sequencing of cDNA libraries

Sequence the core cDNA library(s) using either the Illumina or SoLiD platforms. PE reads (≥30M each library, ≥100 bp) from ~300–400 bp fragments should be generated.

Sequence each of the single-tissue libraries using either the Illumina or SoLiD platforms. SE reads (≥30 M each library, 36–50 bp) from ~300–400-bp fragments should be generated.

5. ASSEMBLY OF A REFERENCE TRANSCRIPTOME

In this step, the PE reads from the core library(ies) will be used to generate a de novo reference assembly of the transcriptome; SE reads from individual tissues will then be mapped to the initial assembly to identify novel reads in the single libraries, and a final, annotated assembly will be generated.

5.1 Quality assessment of sequences and cleaning of reads

NGS transcriptome assemblers such as Velvet/Oases (Zerbino and Birney 2008, Schulz et al. 2012) are not quality-aware. Therefore, short reads need to be pre-processed and checked for quality before assembling. The FASTX-toolkit (Blankenberg et al. 2010, http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) is a collection of command-line programs designed for FASTA or FASTQ short-read sequence files. To use these tools, first check the FASTX-toolkit usage information (http://hannonlab.cshl.edu/fastx_toolkit/) and view the basic help page by typing –h for each one of the programs. The pre-processing pipeline includes assessment of the quality of reads, removal of adapters (optional), trimming, and filtering of low quality sequences.

-

To measure the quality of your short reads, run the fastx_quality_stats program by typing the following commands in a terminal window:

/path/to/fastx-toolkit/bin/fastx_quality_stats –i /path/to/myFASTQfile –o myStatsOutputFile.txt

The output is a tabular file containing the following information for each nucleotide in the cycle (ALL/A/C/G/T/N):- count = Number of bases found in this column.

- min = Lowest quality score value found in this column.

- max = Highest quality score value found in this column.

- sum = Sum of quality score values for this column.

- mean = Mean quality score value for this column.

- Q1 = 1st quartile quality score.

- med = Median quality score.

- Q3 = 3rd quartile quality score.

- IQR = Inter-Quartile range (Q3-Q1).

- lW = 'Left-Whisker' value (for box plots).

- rW = 'Right-Whisker' value (for box plots).

-

To visualize the quality score in a box plot, type the following command in a terminal window:

/path/to/fastx-toolkit/bin/fastq_quality_boxplot_graph.sh –i MyStatsOutputFile.txt –o MyQualityBoxplot.jpg

Tip: To visualize the image, use imaging software.

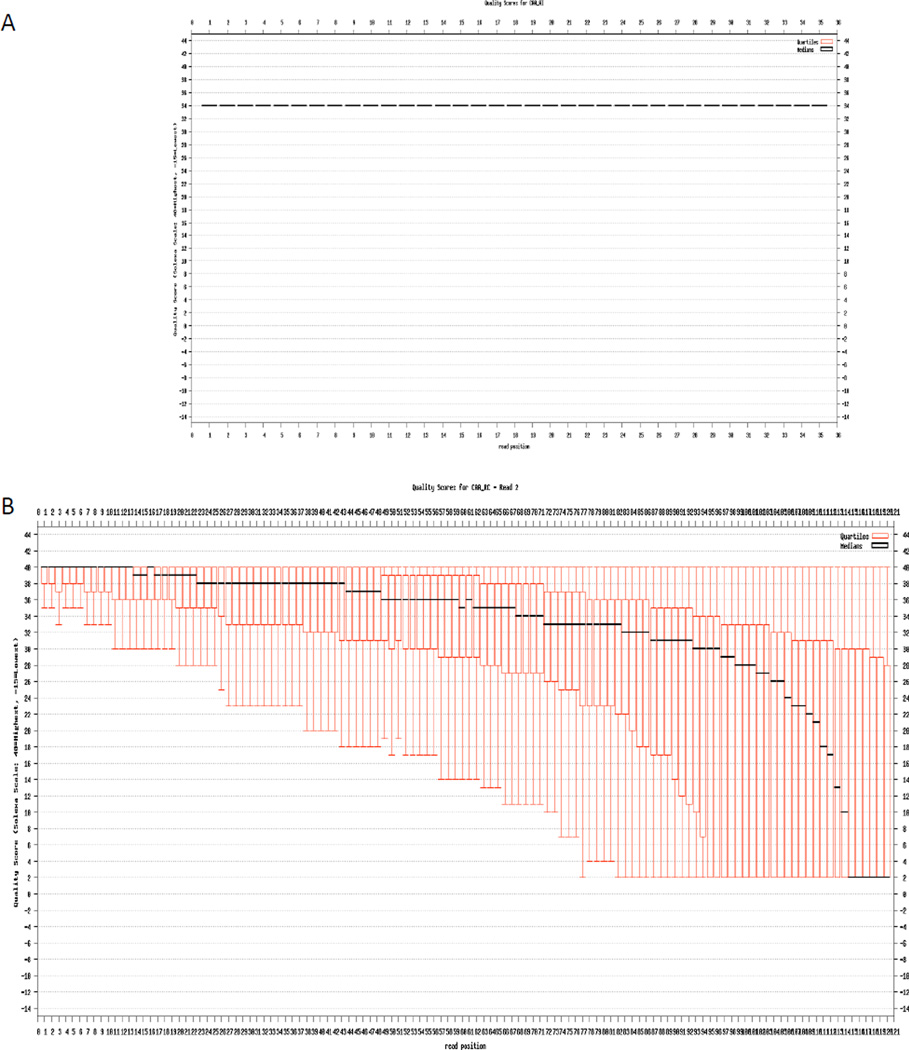

Two sample sequencing runs are shown in Figure 1. Based on base quality scores (Ewing and Green 1998, Ewing et al. 1998), the quality for each base is shown on the Y axis. A minimum quality of 20 is recommended. It is more likely to observe homogeneous quality in “short” reads (36 – 50 bp) than in longer reads (>50 bp) due to a decrease in the quality of the sequence in each sequencing cycle.

- (Optional) To remove low-quality bases from the 3’ end use fastx_trimmer from the FASTX toolkit. The key parameters are: the –i flag to provide the input file; the –o flag to provide the output file; the –t flag to define the number of bases trimming from the 3’ end; and the –m flag to define the minimum read-length to retain. By using –v, it will print a short summary of the process. The following example is based on the box plot of 120-bp reads in Figure 1.

/path/to/fastx-toolkit/bin/fastx_trimmer –v –i /path/to/MySequenceFile.fastq –o MyTrimmedSequence.fastq –t 40 –m 75

-

(Optional) In some cases, the library has been barcoded or has adapters present. If so, the fastx_clipper program from the FASTX toolkit can be used to remove the barcodes or adapters. The key parameters are: the –a flag that specifies the adapter sequence; the -l flag which specifies the minimum length to retain after clipping the adapter; and the –i and –o flags that specify the input and output file, respectively. Using the –v flag will display a summary of the process.

Tip: If the sequences were not trimmed, use the raw sequence file in this step./path/to/fastx-toolkit/bin/fastx_clipper –v –a ATGC –l 36 –i myTrimmedSequence.fastq –o myClippedSequence.fastq

-

To remove low-complexity sequences, run the fastx_artifacts_filter program from the FASTX toolkit by typing the following commands in the terminal window:

Tip: If the sequences were not trimmed or clipped, use the raw sequence file in this step./path/to/fastx-toolkit/bin/fastx_artifacts_filter –v –i myClippedSequence.fastq –o myFilteredSequences.fastq

- To remove the low quality sequences from the sequence files, run the fastq_quality_trimmer from the FASTX toolkit. The key parameters are: the –t flag that specifies the minimum quality to retain (a minimum quality of 20 is recommended); the –l flag that specifies the minimum read length to retain; and the –i and –o flags to specify the input and output files. Note that the input file to run this tool is the output file from the previous step.

/path/to/fastx-toolkit/bin/fastq_quality_trimmer –v –t 20 –l 75 –i MyFilteredSequences.fastq –o MyHighQualitySequences.fastq

- To convert FASTQ to FASTA type the following command in the terminal window:

/path/to/fastx-toolkit/bin/fastq_to_fasta –v –i MyHighQualitySequences.fastq –o MyHighQualitySequences.fasta

Figure 1.

The quality of base calls as a function of cycle length. The base quality is plotted on the y-axis and the cycle number on the x-axis. A) Plot showing 36-bp reads with a quality score of 34 for each base as there is no variation in the quality of the reads. B) Plot showing 120-bp reads with a high variability in quality (range of 40 to 2).

Tip: Some FASTX programs use FASTQ format only, for instance: fastq_quality_trimmer. Tools named as “fastx” can use either FASTA or FASTQ format.

Tip: For PE reads, the cleaning pipeline needs to be applied to each sequence in the pair.

Tip: The estimated time to run each FASTX command will be between 5 and 20 min depending of the file size.

5.2 De novo assembly of reads

The assembly algorithms for NGS are based on the mathematical concept of a graph, which is a set of vertices or nodes that can be connected by edges (MacLean et al. 2009). The Velvet assembler (Zerbino and Birney 2008, Zerbino 2010) uses a refinement of this approach called the de Brujin graph in which the edges are k-mers. In a de Brujin graph, all of the reads are broken into k-mers and the path represents a series of overlapping k-mers that overlap by a length of k-1 (MacLean, et al. 2009, Zerbino and Birney 2008). For de novo transcriptome assembly, Velvet uses the Oases module (Schulz, et al. 2012, Zerbino 2010). It takes the preliminary assembly produced by Velvet and clusters the contigs into small groups called loci. Then, if information is available, it will use the read sequence and the pairing information to infer transcript isoforms (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/~zerbino/oases/). Velvet runs velveth and velvetg. Velveth takes the sequences and produces a hash table; it produces two files, Sequences and Roadmaps. Velvetg is the core of Velvet where the de Brujin graph is built. To use the Velvet/Oases package first check the manual (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/~zerbino/velvet/).

- A de novo assembly of PE read libraries is performed to create the reference transcriptome. To assemble PE reads with Velvet, merge the paired end-sequences into a single file.

- After pre-processing and cleaning, the PE sequences from the pairs will be uneven, i.e., one end may be retained and the other trimmed and eliminated. Therefore, it will be necessary to run select_paired.pl script. This perl script is part of the Velvet package and takes sequences in the FASTA format (convert sequences, if needed, by typing command line in step 7 of section 5.1). To run this program, type the following commands in the terminal window:

/path/to/Velvet/contrib/select_paired/select_paired.pl MyHighQualitySequence_read_1.fasta mySortedForwardReads.fasta MyHighQualitySequence_read_2.fasta mySortedReverseReads.fasta mySingletonsReads.fasta

- Prepare the sequences by merging the forward and reverse reads files into a single file using the perl programs included in the velvet package: shuffleSequences_fasta.pl (or shuffleSequences_fastq.pl). An example using a FASTA format is provided:

/path/to/velvet/shuffleSequences_fasta.pl mySortedForwardReads.fasta mySortedReverseReads.fasta myMergedReads.fasta

- To assemble using Velvet and Oases, it is necessary to run three different commands: velveth, velvetg, and oases. The main arguments for velveth are: the –fasta flag that specifies the file format; the –shortPaired flag that specifies the merged PE short-reads file; and the –short flag that specifies the SE short-read file. Velvetg uses the –read_trkg flag necessary to run oases. The key arguments for oases are: -min_trans_lgth flag that specifies the minimum contig length to retain (by default is 100); and the –ins_length that specifies the insert size between the pairs of the PE library. The following example uses a standard 31 k-mer length:

/path/to/velvet/velveth myOutputDirectory 31 –fasta – shortPaired myMergedReads.fasta –short mySingletonsReads.fasta /path/to/velvet/velvetg myOutputDirectory –read_trkg yes /path/to/oases/oases myOutputDirectory –min_trans_lgth 250 –ins_length 200

Tip: Be aware that the insert size is different for each PE library.

Tip: A k-mer of 31 is a standard k-mer length. It is recommended to determine the optimal k-mer by performing several assemblies with different k-mers. The hash length k must follow these three rules (Zerbino 2008):

It must be an odd number, to avoid palindromes. If you put in an even number, Velvet will just de-increment it and proceed.

It must be below or equal to the MAXKMERHASH length, which is a compilation parameter.

It is less than the read length; otherwise you will not observe any overlap between the reads.

Tip: velveth produces two output files: Roadmaps and Sequences; velvetg produces five output files: contig.fa, stats.txt, PreGraph, Graph2, LastGraph and Log; oases produces three output files: contig-ordering, splicing-events and transcripts.fa

Tip: The assembly may take 1 to 3 hrs to run depending on the file size. The Velvet/Oases algorithms require large amounts of RAM memory and it is recommended that you have at least 60 Gigabytes of RAM.

5.3 Quality of the de novo assembly

To measure the quality of the assembly, examine the size of the assembled transcripts by calculating the N50 length, average contig size, and transcript size distribution; an N50 length around 1 kb is recommended. The completeness of the assembly is obtained by calculating the percentage of reads that map back to the assembly (described in 5.4) and assigning functional annotation (described in 5.6). Typical or good results are indicated by 65–80% of reads mapping to the reference transcriptome; less than 50% mapped reads may indicate an incomplete reference assembly and less than 20% mapped reads may indicate sample contamination

- The N50 is defined as the length of the smallest contig such that at least 50% of the bases can be found in a contig of at least this length. Execute the code in Supplementary file 1 by typing:

/path/to/getN50.pl –f transcripts.fa

5.4 Mapping of reads from single tissue libraries

-

For downstream analyses, a reference set of transcripts needs to be identified from the assembly. During the assembly process, Oases will use read pair and sequence overlap information and generate isoforms which represent true alternative isoforms, alleles, close paralogs, close homologs, or close homeologs (chromosomes in an allopolyploid) depending on the extent of sequence similarity among these transcripts. For most contigs, only a single isoform is generated and this can be used to construct the reference transcriptome. However, for those contigs with multiple isoforms, as a matter of ease and to maximally reflect the transcript, the longest transcript of the contig is retained as the representative transcript. The representative transcripts are then stitched together into a single, artificial pseudomolecule for downstream read mapping. To create the pseudomolecule use the pseudomolecule.pl code (Supplementary file 2). It will generate three output files: a FASTA file containing the pseudomolecule, a gff3 file, and a gtf3 containing the representative transcripts. Execute the code in Supplementary file 2 by typing:

/path/to/pseudomolecule.pl –f transcripts.fa –s species –o myReferenceSequence

Tip: View the basic help page by typing –h for each one of the programs above.

- After pre-processing the reads from the tissue/condition-specific SE libraries (section 5.1), map the reads to the reference pseudomolecule using the TopHat software (Trapnell et al. 2009), a quality-aware short read aligner for RNA-seq data which is built upon the ultrafast short-read mapping program Bowtie (Langmead et al. 2009). The aligner uses the quality of the sequences to perform the alignment; therefore it is highly recommended to use the FASTQ format for the SE reads. To map the SE reads to the reference created in the previous step perform the following steps:

- Create an index of the reference sequence by typing in the terminal window:

/path/to/bowtie/bowtie-build –f myReferenceSequence.fasta myReferenceSequence

- Map the SE reads to the reference pseudomolecule. The main arguments to run TopHat are: the –o flag that specifies the name of the output directory; the –solexa1.3-quals flag that specifies the quality scores are encoded in Phred-scale base-64 for FASTQ files from Illumina GA version 1.3 or later; and the –G flag that specifies the gtf or gff3 file containing the gene models (representative transcripts).

/path/to/tophat/tophat –o myOutputDirectory –solexa1.3-quals –G myReferenceSequence.gtf /path/to/myReferenceSequence /path/to/myCleanedSeReads.fastq

Tip: The Bowtie and SamTools programs (Li et al. 2009) are necessary to run TopHat. To install and use these programs check the manuals (http://tophat.cbcb.umd.edu/manual.html, http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/manual.shtml, http://samtools.sourceforge.net/samtools.shtml).

Tip: The results of the alignment are stored in a BAM file that is a binary file. The SamTools program is used to manipulate this file. The latest version of TopHat (1.4.0) reports the unmapped reads in the output directory as unmapped_left.fq.z; these reads will be used to improve the assembly.

5.5 Improved de novo assembly

- To improve the reference transcriptome, assemble the unmapped SE reads from the previous step (unmapped_left.fq.z) with the PE reads from above (section 5.2). To run Velvet and Oases, use the following commands:

/path/to/velvet/velveth myOutputDirectory 31 –fasta – shortPaired myMergedReads.fasta –short mySingletons.fasta UnmappedReads.fasta /path/to/velvet/velvetg myOutputDirectory –read_trkg yes /path/to/oases/oases myOutputDirectory –min_trans_lgth 250 –ins_length 200

Tip: Before using the unmapped SE reads for the second assembly, convert from FASTQ format to FASTA (if needed) by typing into the command line the commands in Step 7 of section 5.1

Tip: Select random SE reads to use in the assembly if there are too many sequences present and you are memory-limited. You can use the “awk” command for this matter by typing:

awk ‘NR < n’ mySingletons.fasta (or UnmappedReads.fasta) > myRandomSEreads.fasta

“n” = number of lines to print out.

5.6 Quality assessment and functional annotation of the final assembly

-

After assembling SE and PE reads and constructing the final assembly, filter out low-complexity sequences and sequences with gaps equal to or larger than 2/3rds of the sequence length by executing the code in the Supplementary file 3 by typing:

/path/to/lowcomplexity.pl –f /path/to/transcripts.fa –o myCleanedAssembly.fasta

Tip: The script above requires Bioperl modules. To download and install Bioperl, check the manual (http://www.bioperl.org/wiki/Main_Page).

Measure the quality of the assembly as listed in section 5.3.

To annotate the sequences for function use BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Tool; Altschul et al. 1997) and HMMPFAM (Hidden Markov Models – Pfam; Punta et al. 2012).

It is recommended that different directories for each one of these programs be used by typing the following commands in the terminal window:

mkdir myBlastWorkDirectory mkdir myPfamWorkDirectory

Tip: To annotate using BLAST, any collection of publicly available annotated sequences can be used as reference. The Arabidopsis proteome (http://www.arabidopsis.org/) and/or Uniref100 (http://www.uniprot.org/help/uniref; Suzek et al. 2007) are recommended.

Tip: To download, install, and use BLAST, check the manual (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1762/)

-

aTo execute BLAST it is necessary to create a database of your reference sequences (Arabidopsis proteome, Uniref100, etc). To create a database, use the makeblastdb command. The main parameters are: the –in flag that specifies the input file in FASTA format; the –dbtype flag that specifies the molecule type (nucl/prot); and the –parse_seqid flag that enables retrieval of sequences based upon sequence identifiers. Create the database by typing the following commands in the terminal window (the Arabidopsis proteome is used as an example). Make sure that you are working in the BLAST working directory:

/path/to/blast/makeblastdb –in arabidopsis_proteome.fasta – parse_seqid –dbtype prot

-

bFollowing the example above, run BLAST using the blastx search application that will translate the query sequences. The main parameters are: the –db flag that specifies the database name; the –query flag that specifies the name of the sequence file; the –out flag that specifies the name of the file to write the application output; the –evalue flag that specifies the expectation value threshold for saving hits; the –num_alignments flag that specifies the number of alignments to show in the BLAST output; and the –num_descriptions flag specifies the number of one-line descriptions shown in the BLAST output. To run blastx use the following command line:

/path/to/blast/blastx –db arabidopsis_proteome.fasta –query myCleanedAssembly.fasta –out myOutputBlast.txt –evalue 10e-10 – num_descriptions 20 –num_alignments 20

-

cPfam families are divided into two categories: Pfam-A entries consist of high-quality manually curated families and Pfam-B families, which are automatically generated from the ProDom database and represented by a single alignment (Finn, et al. 2010). To annotate the assembled sequences using the Pfam domains (Punta et al. 2012) it is necessary to download the database from

ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/databases/Pfam/current_release/.

Tip: To download, install and use HMM3, check the manual (http://hmmer.janelia.org/). The following command line is compatible with HMM3 (Finn et al. 2011) and Pfam 24 or later (ftp://ftp.sanger.ac.uk/pub/databases/Pfam/releases/)

-

dTo search protein sequences against the Pfam HMM library, type the following command in the terminal window (make sure you are working in the working Pfam directory):

/path/to/PfamScan/pfam_scan.pl –fasta myCleanedAssembly.fasta –dir .

Tip: Running these programs will take hours to several days depending on the database size and available RAM.

6. ASSESSMENT OF EXPRESSION ABUNDANCES

In this step, expression abundances will be determined using the reads from the single-tissue libraries.

6.1 Mapping of reads to final de novo assembly

Create a pseudomolecule defining the representative transcripts as shown in Step 1 of section 5.4

Map the SE reads to the pseudomolecule of the final de novo assembly as shown in Step 2 of section 5.4

6.2 Quantification of the transcript abundances

- To estimate the transcript abundances in the transcriptome, use the Cufflinks program (Trapnell et al. 2010). Cufflinks accepts aligned RNA-Seq reads and assembles the alignments into a parsimonious set of transcripts, then estimates the relative abundances of these transcripts based on how many reads support each one. Properly normalized, the RNA-Seq fragment counts can be used as measures of relative abundance of transcripts. Cufflinks measures transcript abundances in Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per million fragments mapped (FPKM). In this case, the transcripts represent the exon models. Cufflinks uses the following parameters: the –G flag that specifies the gtf or gff3 file containing the gene models; and the –o flag that specifies the name of the output directory. The last argument that Cufflinks will take is the alignment file in BAM format.

/path/to/cufflinks/cufflinks –G myReferenceSequence.gtf –o myOutputDir accepted_hits.bam

Tip: To download, install and use Cufflinks check the manual (http://cufflinks.cbcb.umd.edu/index.html)

Tip: The estimated time to run Cufflinks is between 5 and 30 min for each BAM file.

Tip: The genes.expr file contains the transcript abundances and the expression values are reported in FPKM.

6.3 Quality assessment of the expression matrix

- To visualize this file in the terminal window, use one of the following commands:

less genes.expr more genes.expr

The genes.expr file is a tabular file that can be easily exported to Excel. If expression values were estimated for several SE libraries, it is easier to visualize them in a table as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Example of a matrix table containing FPKM values derived from several RNA-Seq experiments.

| Transcript ID | Flower | Mature seed | Primary tap root |

Sterile seedling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aba_locus_10000_iso_5_len_2002_ver_2 | 53.3573 | 16.8643 | 60.4732 | 88.7859 |

| Aba_locus_10001_iso_1_len_768_ver_2 | 1.28434 | 0.991732 | 17.2949 | 0 |

| Aba_locus_10003_iso_4_len_1024_ver_2 | 4.76948 | 0 | 3.62686 | 27.7211 |

| Aba_locus_10004_iso_3_len_1395_ver_2 | 148.113 | 38.1735 | 83.8227 | 61.5356 |

| Aba_locus_100067_iso_1_len_323_ver_2 | 0 | 0 | 2.55721 | 2.97049 |

| Aba_locus_10007_iso_1_len_1475_ver_2 | 12.3071 | 11.9107 | 8.68283 | 8.25411 |

| Aba_locus_10008_iso_8_len_2119_ver_2 | 71.3359 | 55.5804 | 104.715 | 69.1209 |

Tip: Within a single library, if the FPKM values for most of the genes are zero, it could be an indicator that the library is contaminated and should be investigated further.

7. SUMMARY

Robust, inexpensive methods for transcriptome sequencing and assembly are available. Meaningful approximations of gene function can be made using open-source software that includes well supported biochemical function annotations. When coupled to determination of expression abundances across a developmental or treatment series, inferences in biological processes can be made. Current limitations of de novo transcriptome sequencing include: lack of resolution of isoforms, alleles, paralogs, homologs, and homeologs within a specific transcript assembly; presence of partial transcripts and chimeras; and lack of full representation of all transcripts. However, for the majority of transcripts in many medicinal plant species, access to a transcriptome assembly and expression abundances is a rapid, efficient, inexpensive method to access genes relevant to biochemical pathways of interest.

8. USEFUL LINKS

-

FASTX TOOL KIT

-

Velvet/Oases Package

-

Bowtie, Tophat & Cufflinks

http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/manual.shtml

-

Samtools

-

Protein Sequences & Protein Domain Databases

-

BLAST & HMMER

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for medicinal plant transcriptome work was provided by a grant to J.C., D.D.P., and C.R.B. from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1RC2GM092521) and from the Michigan State University GREEEN program to C.R.B (GR11-181).

REFERENCES

- Adams MD, Soares MB, Kerlavage AR, Fields C, Venter JC. Rapid cDNA sequencing (expressed sequence tags) from a directionally cloned human infant brain cDNA library. Nat Genet. 1993;4:373–380. doi: 10.1038/ng0893-373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arumuganathan K, Earle E. Nuclear DNA content of some important plant species. Plant Molecular Biology Reporter. 1991;9:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, Hall KP, Evers DJ, Barnes CL, Bignell HR, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blankenberg D, Gordon A, Von Kuster G, Coraor N, Taylor J, Nekrutenko A. Manipulation of FASTQ data with Galaxy. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1783–1785. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl MC, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Mistry J, Tate J, Coggill P, Heger A, Pollington JE, Gavin OL, Gunasekaran P, Ceric G, Forslund K, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D211–D222. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaillon O, Aury JM, Noel B, Policriti A, Clepet C, Casagrande A, Choisne N, Aubourg S, Vitulo N, Jubin C, et al. The grapevine genome sequence suggests ancestral hexaploidization in major angiosperm phyla. Nature. 2007;449:463–467. doi: 10.1038/nature06148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean D, Jones JD, Studholme DJ. Application of 'next-generation' sequencing technologies to microbial genetics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:287–296. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, Berka J, Braverman MS, Chen YJ, Chen Z, et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKernan KJ, Peckham HE, Costa GL, McLaughlin SF, Fu Y, Tsung EF, Clouser CR, Duncan C, Ichikawa JK, Lee CC, et al. Sequence and structural variation in a human genome uncovered by short-read, massively parallel ligation sequencing using two-base encoding. Genome Res. 2009;19:1527–1541. doi: 10.1101/gr.091868.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paux E, Roger D, Badaeva E, Gay G, Bernard M, Sourdille P, Feuillet C. Characterizing the composition and evolution of homoeologous genomes in hexaploid wheat through BAC-end sequencing on chromosome 3B. Plant J. 2006;48:463–474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paux E, Sourdille P, Salse J, Saintenac C, Choulet F, Leroy P, Korol A, Michalak M, Kianian S, Spielmeyer W, et al. A physical map of the 1-gigabase bread wheat chromosome 3B. Science. 2008;322:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1161847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Punta M, Coggill PC, Eberhardt RY, Mistry J, Tate J, Boursnell C, Pang N, Forslund K, Ceric G, Clements J, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D290–D301. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson G, Schein J, Chiu R, Corbett R, Field M, Jackman SD, Mungall K, Lee S, Okada HM, Qian JQ, et al. De novo assembly and analysis of RNA-seq data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:909–912. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz MH, Zerbino DR, Vingron M, Birney E. Oases:Robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics. 2012 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts094. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shendure J, Ji H. Next-generation DNA sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1135–1145. doi: 10.1038/nbt1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulaev V, Sargent DJ, Crowhurst RN, Mockler TC, Folkerts O, Delcher AL, Jaiswal P, Mockaitis K, Liston A, Mane SP, et al. The genome of woodland strawberry (Fragaria vesca) Nat Genet. 2011;43:109–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzek BE, Huang H, McGarvey P, Mazumder R, Wu CH. UniRef: comprehensive and non-redundant UniProt reference clusters. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1282–1288. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Potato Genome Sequencing Consortium. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature. 2011;475:189–195. doi: 10.1038/nature10158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino D. Velvet Manual. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Zerbino DR, Birney E. Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs. Genome Res. 2008;18:821–829. doi: 10.1101/gr.074492.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.