Abstract

The pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) increases expression of CD38 (a membrane-associated bifunctional enzyme regulating cyclic ADP ribose), and enhances agonist-induced intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) responses in human airway smooth muscle (ASM). We previously demonstrated that caveolae and their constituent protein caveolin-1 are important for ASM [Ca2+]i regulation, which is further enhanced by TNFα. Whether caveolae and CD38 are functionally linked in mediating TNFα effects is unknown. In this regard, whether the related cavin proteins (cavin-1 and -3) that maintain structure and function of caveolae play a role is also not known. In the present study, we hypothesized that TNFα effects on CD38 expression and function in human ASM involve caveolae. Caveolar fractions from isolated human ASM cells expressed CD38 and its expression was upregulated by exposure to 20 ng/ml TNFα (48h). ASM cells expressed cavin-1 and cavin-3, which were also upregulated by TNFα. Knockdown of caveolin-1, cavin-1 or cavin-3 (using siRNA) all significantly reduced CD38 expression and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity in the presence or absence of TNFα. Furthermore, caveolin-1, cavin-1 and cavin-3 siRNA reduced [Ca2+]i responses to histamine under control conditions, and blunted the enhanced [Ca2+]i responses in TNFα-exposed cells. These data demonstrate that CD38 is expressed within caveolae and its function is linked to the caveolar regulatory proteins caveolin-1, cavin-1 and -3. The link between caveolae and CD38 is further enhanced during airway inflammation demonstrating the important role of caveolae in regulation of [Ca2+]i and contractility in the airway.

Keywords: Plasma membrane, ADP ribosyl cyclase, Lung, Asthma, Cavin

1. INTRODUCTION

Intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) plays an important role in airway smooth muscle (ASM) contraction and relaxation. Agonist-induced [Ca2+]i responses involve Ca2+ influx and sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ release [1-6].

Inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor- alpha (TNFα) and interleukins such as IL-13 have been implicated as mediators in the pathophysiology of reactive airway diseases such as asthma [7-9] and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [10, 11]. For example, we and others have shown that TNFα enhances ASM contractility by increasing agonist-induced [Ca2+]i responses [12-18]. We and others have shown that in ASM, SR Ca2+ release involves both inositol trisphosphate receptor [1-3] and ryanodine receptor channels [4, 19]. Several studies, including our own, have shown that the second messenger cyclic-ADP-ribose (cADPR) is involved in Ca2+ release via ryanodine receptor channels [6, 20]. cADPR is synthesized and degraded by the bifunctional ectoenzyme CD38 via ADP-ribosyl cyclase and cADPR hydrolase activities, respectively [21]. Indeed, the CD38/cADPR pathway has been implicated in [Ca2+]i regulation in several smooth muscle types including ASM [6, 22-28]. Other studies suggest that the CD38/cADPR signaling pathway contributes to TNFα-induced augmentation of [Ca2+]i responses in ASM [29].

In a recent study [25], we demonstrated that the extent of store-operated Ca2+ entry (SOCE) in human ASM cells is modulated by the level of CD38 expression, which suggest that CD38 effects do not necessarily involve cADPR. Accordingly, the mechanisms that regulate plasma membrane CD38 levels become important. In this regard, we previously reported [30] the presence of caveolae and their constituent proteins caveolin-1 and -2 in human ASM as well as the role of these plasma membrane mechanisms in [Ca2+]i regulation. The importance of caveolae lies in the facts that they express a number of [Ca2+]i and other regulatory proteins, and that ASM caveolae and caveolin-1 expression are increased following TNFα exposure [14]. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that CD38 is expressed within caveolae, and modulated by caveolar proteins, providing an avenue for TNFα to upregulate CD38 in airway inflammation.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Isolation of Human ASM Cells

The techniques for isolation of human ASM cells have been previously described [30, 31]. Briefly, in accordance with previously approved procedures and considered exempt from Human Subjects classification by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, human 3rd to 6th generation bronchi were obtained from discarded surgical specimens and ASM cells enzymatically dissociated as described previously [30, 31]. Cells were seeded into culture flasks, maintained under normal conditions (21% O2, 5% CO2; 37°C) and used for experiments under serum starved conditions prior to passage 3 of subculture. Validation of ASM cell phenotype was performed by Western analysis and RT-PCR for smooth muscle markers [30, 31].

2.2. CD38 Overexpression

As recently described [25], full length CD38 was generated using RT-PCR and primers designed from published sequence (Accession # D84276) that include the endogenous translation start and stop codons (Forward primer sequence: 5’-ACCCCGCCTGGAGCCCTATG-3’ Reverse primer sequence: 5’-GCTAAAACAACCACAGCGACTGG-3’). A green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged CD38 DNA construct was constructed using standard procedures, and ASM cells were transfected with GFPCD38 or Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen) alone according to manufacturer's protocol. Cells were incubated with the transfection mix in DMEM/F12 media without serum for 24 h and analyzed for CD38 expression and function as previously described [25]. For [Ca2+]i studies, DMEM/F12 containing 10% FBS was added 4 h post-transfection and maintained for 24 h. This medium was replaced with serum free DMEM/F12 media for an additional 48 h to drive cells to quiescence prior to [Ca2+]i measurements.

2.3 Preparation of Caveolar Membranes

We have previously described techniques for preparation of caveolin-rich membranes from human ASM cells [30]. Briefly, ASM cells were homogenized in cold buffer A (0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 20 mM Tricine, pH 7.8), layered onto a 30% Percoll gradient, and centrifuged at 84,000 × g for 30 min. The crude membrane fraction was then sonicated, resuspended and normalized to equal protein concentration and a linear 20% to 10% OptiPrep gradient was layered on top for re-centrifugation. The upper membrane layer (containing caveolae) was collected for further experimentation. Equal volumes of caveolae enriched fraction were loaded for western blot analysis to account for comparable measurements of caveolar proteins within caveolae.

2.4. Caveolin-1, Cavin-1, and Cavin-3 Knockdown

The technique for knocking down of caveolar proteins in human ASM using siRNA has also previously been described [30, 32]. siRNA duplex oligonucleotides were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). ASM cells at 60% confluence were transfected using 50nM siRNA and Lipofectamine in DMEM F/12 without FBS. Fresh growth medium was added 6 h following transfection and cells processed after 48 h. Efficacy of siRNA knockdown was verified by Western analysis.

2.5. Measurement of ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity

The fluorescence-based assay of the conversion of the NAD analog, NGD, to the non-hydrolyzable fluorescent product cGDPR as an index of ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity has been previously described [33]. Briefly, normal medium was replaced with HBSS containing 400μM NGD with or without TNFα. HBSS with NGD in cells without cells served as background. After 24 h (during which cells were maintained under standard culture conditions), an aliquot of medium was removed and fluorescence measured (excitation 305 nm, emission 410 nm; Amersham spectrofluorometer). Changes in fluorescence above background were considered as valid conversions from NGD to cGDPR.

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

Standard techniques were used to separate proteins of interest by SDS-PAGE, transfer to PVDF membranes, blocking with 5% milk, incubation overnight with 1 μg/ml primary antibodies and detection of bands with either horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies or chemiluminescence substrate (Supersignal West Pico, Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL). Signal were developed using Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent substrate or far-red fluorescent dye-conjugated antibodies. Blots were imaged on a Kodak Image Station 4000MM (Carestream Health, New Haven, CT) or a LiCor OdysseyXL system, and quantified using densitometry.

2.7. Fluorescence [Ca2+]i imaging

These techniques have been extensively described [25, 34, 35]. Cells were incubated for 45 min in 5 μM fura-2/AM. ASM cells were initially perfused with 2.5 mM Ca2+ HBSS and baseline fluorescence levels were established. The [Ca2+]i responses of 15-30 cells per chamber were achieved using software-defined regions.The ratiometric measurements of 510 nm emissions following 340/380 nm excitations were recorded every 750 ms using a video fluorescence imaging system (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). In regard to the histamine-induced [Ca2+]i responses, ( the amplitudes of [Ca2+]i responses were calculated by subtracting the baseline [Ca2+]i level from the peak [Ca2+]i responses.[22, 25].

2.8. Materials

Antibodies to Caveolin-1 (Abcam, #ab18199), CD38 (Epitomics, #2935-1), Cavin-1 (Novus Biologicals, #NB100-60635), Cavin-3 (Abcam, #ab76676), and GAPDH (Cell Signaling, #2118) were purchased as listed. DMEM, antibiotic/antimycotic mixture as well as Fura-2 were obtained from Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY. Unless mentioned otherwise all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO.

2.9. Statistical analysis

Experiments were performed using ASM cells derived from at least 5 different patients, although not all protocols were performed in each sample. Each protocol was repeated at least 5 times. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t test or 2-way ANOVA with repeated measures when necessary (Bonferroni correction for repeated measures). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Caveolar Protein Expression and Upregulation with TNFα

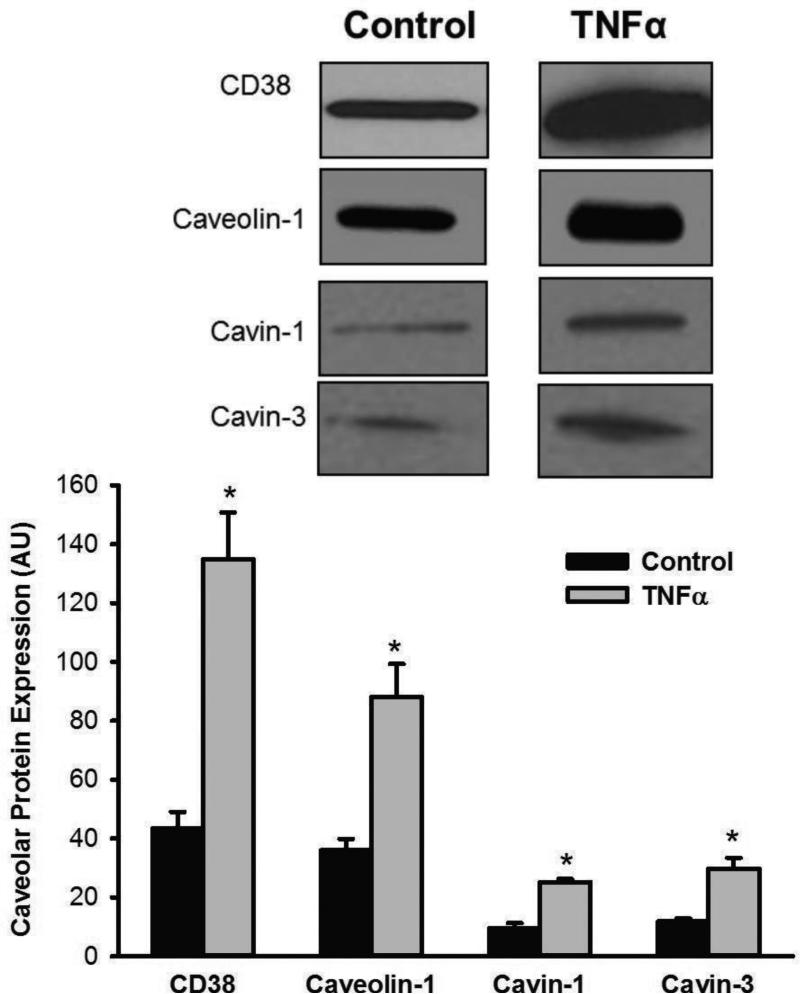

We previously demonstrated caveolin-1 expression and its upregulation within caveolar fractions following TNFα exposure [14]. In the present study, we found that CD38 as well as the caveolar structural regulatory proteins cavin-1 and cavin-3 are expressed within caveolar fractions of human ASM cells (Figure 1). All these proteins are significantly upregulated in the presence of TNFα (Figure 1; p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Caveolar expression of CD38. In caveolar fractions of human ASM cells, considerable CD38 expression was observed at baseline. Caveolar fractions expressed the constitutive protein caveolin-1 as well as the structural regulatory proteins cavin-1 and cavin-3 that determine caveolin-1 insertion into plasma membrane (and thus invagination) and caveolin internalization, respectively. Overnight exposure to TNFα significantly increased expression of all these proteins (CD38, caveolin-1, cavin-1, and cavin-3). * in bar graph indicates significant TNFα effect (p<0.05).

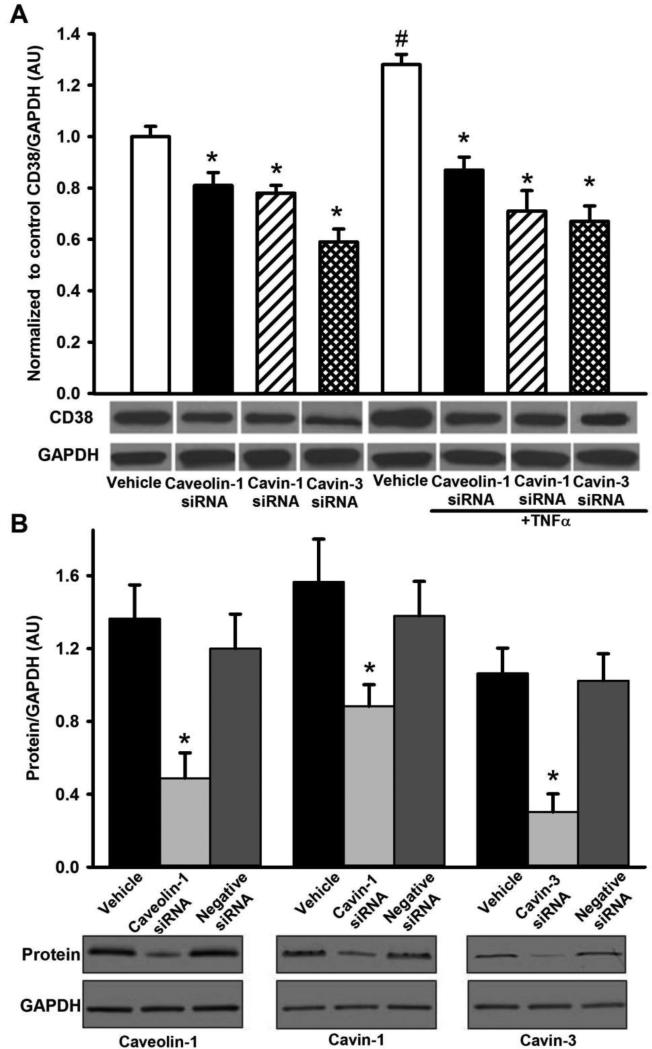

3.2. Effect of Caveolar Protein knockdown on CD38 expression

siRNA suppression of caveolin-1, cavin-1, or cavin-3 expression all significantly reduced CD38 expression in human ASM (Figure 2A, p<0.05). Surprisingly, cavin-3 siRNA was most effective in reducing CD38 expression. The significant increase in CD38 expression following TNFα exposure was still blunted by knockdown of caveolin-1, cavin-1 or cavin-3 (Figure 2A, p<0.05), and to a greater extent compared to non-TNFα exposed cells. Here too, cavin-3 siRNA was most effective. Transfection with small interference RNA (siRNA) specific for caveolin-1, cavin-1 or cavin-3 resulted in significant reduction in specific protein expression.Vehicle (Lipofectamine) or negative siRNA had no significant effect on protein expression (Figure 2B, p<0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect of caveolar protein knockdown on CD38 expression in human ASM cells. siRNA knockdown of caveolin-1, cavin-1, or cavin-3 all significantly reduced caveolar CD38 expression in human ASM at baseline. TNFα-induced increase in CD38 expression was substantially blunted by siRNA against caveolin-1, cavin-1, and particularly cavin-3 (A). The siRNA efficacy of all three caveolar proteins was verified using western blot analysis (B). Values are mean ± SEM. * indicates significant siRNA effect, # indicates significant effect of TNFα (p< 0.05).

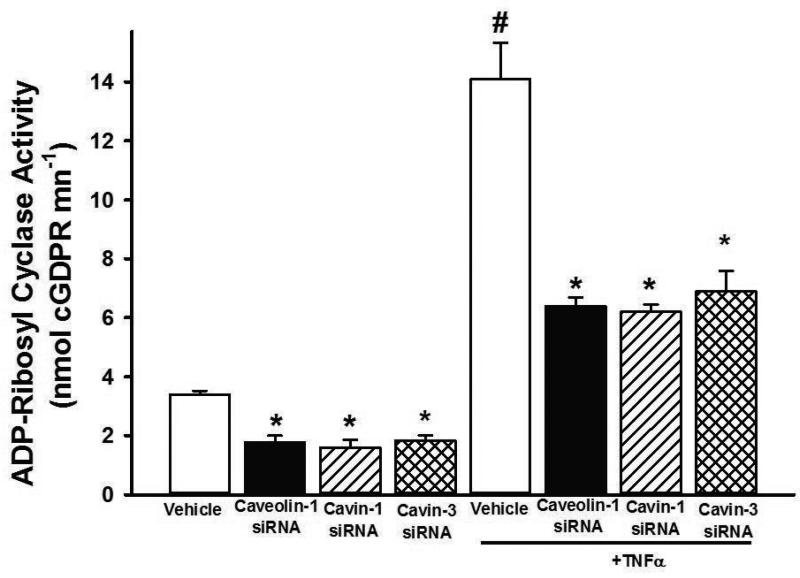

3.3. Effect of Caveolar Protein Knockdown on ADP-Ribosyl Cyclase Activity

Compared to baseline, exposure to TNFα significantly enhanced ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity (Figure 3, p<0.05) consistent with increased CD38 expression. siRNA-induced suppression of caveolin-1, cavin-1, and cavin-3 all significantly reduced ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity in ASM cells with or without TNFα exposure (Figure 3, p<0.05), with proportionately greater effects in TNFα-exposed cells.

Figure 3.

Effect of caveolar protein knockdown on ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity. siRNA knockdown of caveolin-1, cavin-1 or cavin-3 significantly reduced ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity. TNFα enhancement of cyclase activity was reduced to an even greater extent by siRNAs against all three proteins. Values are mean ± SEM. * indicates significant siRNA effect, # indicates significant effect of TNFα (p< 0.05).

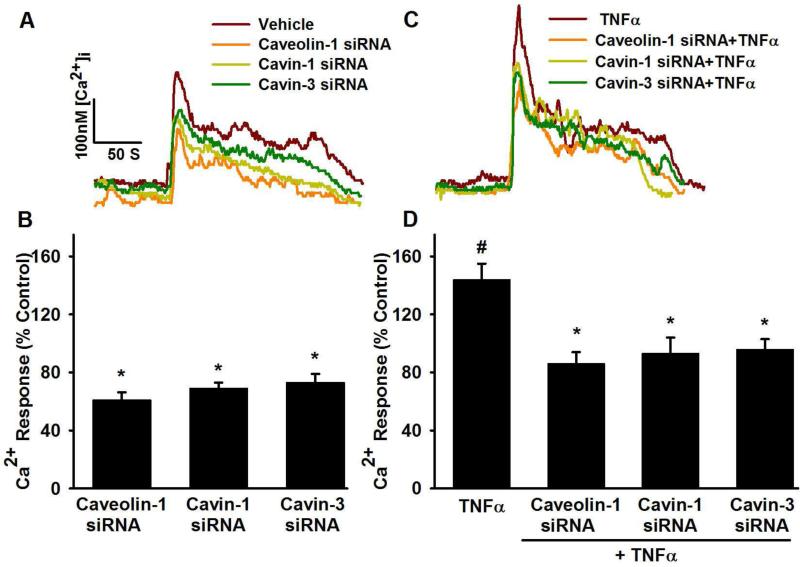

3.4. Effect of Caveolin-1, Cavin-1 and Cavin-3 siRNA on [Ca2+]i response to agonist

In fura-2 loaded control (i.e. non-transfected, non-TNFα exposed, Lipofectamine only) ASM cells, baseline [Ca2+]i was ~100-180 nM (mean 154 ± 14 nM). Exposure to 10 μM histamine produced characteristic biphasic [Ca2+]i responses, which we have also reported previously [14]. Consistent with previous results [14, 15], exposure to TNFα significantly increased [Ca2+]i responses to histamine compared to control (Figure 4C,D; p<0.05). In cells exposed to caveolin-1, cavin-1 or cavin-3 siRNA, [Ca2+]i responses to histamine were significantly reduced in comparison to vehicle (Figure 4 A,B, p<0.05). In cells exposed to TNFα, caveolin-1, cavin-1, and cavin-3 siRNA blunted the enhancement of [Ca2+]i responses due to this cytokine (Figure 4C,D; p<0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect of caveolin-1, cavin-1 and cavin-3 siRNA on intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) responses to agonist in human ASM cells. Compared to control cells (non-transfected, treated with Lipofectamine vehicle only), caveolin-1, cavin-1 and cavin-3 siRNA treated cells showed significantly reduced [Ca2+]i responses to 10 μM histamine (A and B). TNFα significantly enhanced [Ca2+]i responses to histamine. In the presence of TNFα, all caveolin-1 siRNA, cavin-1 siRNA and cavin-3 siRNA treated cells still showed significantly smaller [Ca2+]i responses to histamine (C and D). Values are mean ± SEM. * indicates significant siRNA effect, # indicates significant effect of TNFα (p< 0.05).

3.5. CD38 overexpression and [Ca2+]i responses

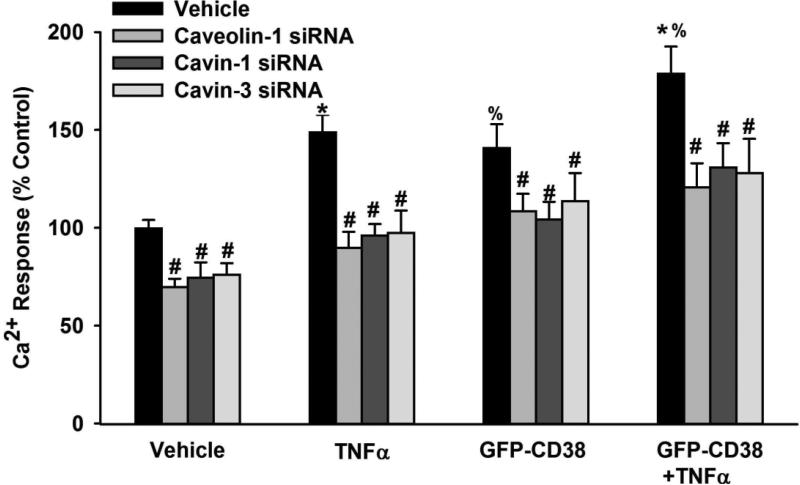

Overexpression of CD38 increased [Ca2+]i responses to histamine compared to vehicle (Lipofectamine only; Figure 5, p<0.05). This enhancing effect was as pronounced as with exposure to TNFα. The combination of CD38 overexpression and TNFα exposure even further enhanced [Ca2+]i responses (Figure 5, p<0.05). To investigate whether the increased [Ca2+]i responses in the presence of CD38 overexpression and/or TNFα are linked to changes in caveolar proteins, we used caveolin-1, cavin-1 or cavin-3 siRNA under these experimental conditions. Downregulation of caveolin-1, cavin-1 or cavin-3 using siRNA significantly reduced [Ca2+]i responses under all these experimental conditions (control, TNFα, CD38 overexpression, and CD38 overexpression plus TNFα; Figure 5, p<0.05).

Figure 5.

Role of caveolin-1, cavin-1 and cavin-3 in the regulation of CD38 effects. Overexpression of CD38 using a GFP-tagged construct resulted in a significant increase in [Ca2+]i responses to 10 μM histamine. This effect is as pronounced as the TNFα-induced increase in [Ca2+]i responses. Combination of TNFα and GFP-CD38 even further enhanced the increase in [Ca2+]i responses. Under these different conditions, caveolin-1, cavin-1 or cavin-3 siRNA treated cells showed significantly reduced [Ca2+]i responses under all conditions (vehicle; CD38 overexpression, TNFα, CD38 overexpression plus TNFα) suggesting that caveolar proteins modulate CD38 effects. Values are mean ± SEM. # indicates significant siRNA effect, * indicates significant effect of TNFα (compared to control), % indicates significant CD38 effect (p< 0.05).

4. DISCUSSION

In this study, we present novel data demonstrating that caveolar CD38 expression is linked to TNFα-induced augmentation of [Ca2+]i responses to agonist stimulation in ASM. In this regard, we found that CD38 expression within caveolae is regulated by the cavin proteins that happen to be important for caveolar structure (cavin-1) and trafficking (cavin-3). Exposure to TNFα upregulates such mechanisms, resulting in enhanced caveolar CD38 which in turn leads to increased ADP ribosyl cyclase activity and [Ca2+]i. However, such enhancement of CD38 is not unidirectional in the sense that caveolae in turn can regulate CD38 function as well. This is demonstrated by the findings that inhibition of caveolin-1, cavin-1 and cavin-3 expression leads to blunting of CD38 effects on [Ca2+]i responses in the presence or absence of cytokine. The relevance of these findings lies in the recognition that both CD38 [6, 22-28] and caveolae [14, 32, 36] are important regulators of ASM [Ca2+]i and contractility, and increased expression of either mechanism contributes to increased airway contractility [14, 25, 29, 32, 36]. Accordingly, structural and functional linkage between the two highlights a potentially synergistic pathway by which cytokines or other inflammatory factors can enhance airway contractility in the setting of airway diseases.

4.1. CD38 in ASM

We and others have demonstrated that CD38 exists in ASM, and is involved in regulation of [Ca2+]i and contractility [25, 29, 37-39]. Furthermore, the link between CD38 and cADPR, synthesized by ADP-ribosyl cyclase and degraded by cADPR hydrolase, has also been well-established in vitro [37, 40, 41] as well as in vivo using CD38 knockout mice [26, 42, 43]. Intracellular cADPR levels can be modulated via CD38 expression and function, for example by neurotransmitters and cytokines (IL-1, TNFα) [29, 44, 45]. In human ASM cells, we previously reported that TNFα increases CD38 expression as well as activity as determined using an NGD assay: effects inhibited by CD38 siRNA [25]. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that the enzymatic machinery for cADPR metabolism exists in ASM [46], and is important for [Ca2+]i regulation by showing that exogenous cADPR modulates SR Ca2+ release via ryanodine channels [6]. In human ASM, cADPR production occurs with several bronchoconstricting agents (acetylcholine, endothelin-1 and histamine) [20, 22]. And finally, beyond cADPR, CD38 also has the potential to modulate [Ca2+]i via effects on Ca2+ influx mechanisms such as TRPC3 [25]. Overall, these data link CD38 and [Ca2+]i regulation in ASM. Furthermore, they demonstrate that these relationships can play a role in cytokine enhancement of [Ca2+]i in ASM. The current study now demonstrates that such links involve caveolar CD38 with an additional role for caveolin-1 in regulating CD38 effects.

4.2. TNFα, CD38 and ASM

The important role of TNFα in airway inflammation and hyperreactivity has been well-recognized [8, 47, 48]. Here, several targets and mechanisms for TNFα effects, including [Ca2+]i regulatory pathways, have been identified in ASM [13, 49]. Relevant to this study, we and others [14, 50] have shown that TNFα enhances caveolin-1 expression and signaling in human ASM. Studies in human ASM, including our own, have already shown that TNFα increases CD38 expression [25, 29, 35]. Furthermore, the CD38/cADPR signaling pathway is involved in TNFα-induced increase in airway responsiveness [29]. For example, adenoviral mediated anti-sense CD38 transfection leads to blunted [Ca2+]i responses to agonist [51], while CD38 overexpression leads to enhanced [Ca2+]i responses as well as store-operated Ca2+ influx [25]. The present study shows that TNFα induced alterations in CD38 are linked to changes in caveolar proteins which in turn can regulate CD38 function.

4.3 Caveolae in ASM

Caveolae are flask-shaped invaginations of the plasma membrane that are enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids, and integral membrane proteins called caveolins. Caveolin-enriched domains harbor a range of proteins and facilitate binding of intracellular as well as extracellular moieties, and therefore can have profound effects on signaling between plasma membrane regulatory components and intracellular structures. There is currently no information on caveolar localization of CD38 in any tissue. In this regard, the results of the current study are novel. By co-expressing CD38 along with agonist receptors and multiple regulatory proteins such as agonist receptors and influx channels, caveolae may facilitate interactions between these proteins and thus enhance [Ca2+]i and other signaling. Accordingly, mechanisms that regulate caveolar structure and the protein composition of caveolae become important in the context of regulatory proteins such as CD38.

The results of the present study show that in human ASM, caveolar CD38 expression is regulated by caveolin-1 as well as two cavins that themselves modulate caveolar structure and function. ASM from different species have now been shown to express caveolin-1 (and to a lesser extent caveolin-2) [30, 52-54]. We and others have also shown that caveolin-1 expression and its effects on [Ca2+]i per se are enhanced in the presence of cytokines such as TNFα. Such effects are mediated, at least in part, by caveolin-1 itself, as well as signaling intermediates such as MAPK and NFκB. Thus caveolin-1 is an integral aspect of caveolar effects in ASM. What is novel in this study is the demonstration that caveolin-1 regulates the expression and function of an important enzyme such as CD38 that is not simply due to altered caveolar levels per se.

In addition to caveolin-1, two relatively novel regulatory proteins, cavin-1 (or PTRF) and cavin-3 (or SRBC) also appear to be important for CD38 expression and its activity. There is currently very little information on cavin expression patterns in ASM, or their role in ASM caveolar expression/function or other pathways. Here, the results of the present study showing robust cavin-1 and cavin-3 expression in human ASM are also novel, as are the data that TNFα substantially increases expression of both proteins. A primary role of these proteins is control of caveolin-1 levels within caveolae (by enhancing plasma membrane insertion vs. internalization). Accordingly, the overall level of caveolin-1 (a relatively stable protein when in the plasma membrane) is likely driven by a balance between these regulators. Here, the increase in cavin-3 with TNFα is surprising since that should lead to reduced plasma membrane caveolin-1, and not an increase as has been previously reported [55]. While the focus of the present study was not on the role of cavins in caveolin control per se, it is possible to hypothesize that the relative contribution of cavin-1 (insertion) vs. cavin-3 (internalization) is different. However, what is more interesting is that cavin-3 in particular appears to regulate caveolar CD38 levels. Given cavin-3's role, this cannot be a result of increased caveolin-1 (or caveolae) but must reflect an entirely different mechanism that remains to be explored. Nonetheless, the effects of cavins on CD38 expression (and consequent function) demonstrate the importance of caveolar proteins in regulation of CD38, particularly in the presence of cytokines.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that TNFα induced augmentation of [Ca2+]i responses to agonist in human ASM is mediated via changes in caveolar CD38, driven by effects of caveolin-1 as well as the regulatory proteins cavin-1 and cavin-3. Such changes may further lead to increased cADPR levels, and thus increased [Ca2+]i responses due to release via ryanodine channels, which can contribute to the enhanced airway contractility that occurs with inflammation.

Highlights.

Caveolae are plasma membrane invaginations important in lung responses to inflammation

We show that caveolar proteins caveolin-1 and cavins in human airway smooth muscle regulate the ectoenzyme CD38

CD38 is a key regulator of intracellular calcium and airway responses to inflammation

Inflammation enhances caveolar CD38 resulting in increased second messenger and intracellular calcium

Overall, caveolar proteins regulate inflammatory responses in airway relative to asthma via altered CD38 expression and function

Acknowledgments

Funding Support: Supported by NIH R01 grants HL090595 (Pabelick), HL088029 and HL56470 (Prakash), and HL074309 (Sieck).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stephens NL. Airway smooth muscle. Lung. 2001;179:333–373. doi: 10.1007/s004080000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall IP. Second messengers, ion channels and pharmacology of airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:1120–1127. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billington CK, Penn RB. Signaling and regulation of G protein-coupled receptors in airway smooth muscle. Respir Res. 2003;4:2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannan MS, Prakash YS, Brenner T, Mickelson JR, Sieck GC. Role of ryanodine receptor channels in Ca2+ oscillations of porcine tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L659–664. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.4.L659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prakash YS, Kannan MS, Sieck GC. Regulation of intracellular calcium oscillations in porcine tracheal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:C966–975. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.272.3.C966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prakash YS, Kannan MS, Walseth TF, Sieck GC. Role of cyclic ADP-ribose in the regulation of [Ca2+]i in porcine tracheal smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:C1653–1660. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.274.6.C1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah A, Church MK, Holgate ST. Tumour necrosis factor alpha: a potential mediator of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25:1038–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1995.tb03249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas PS, Yates DH, Barnes PJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases airway responsiveness and sputum neutrophilia in normal human subjects. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1995;152:76–80. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.1.7599866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas PS. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha: the role of this multifunctional cytokine in asthma. Immunol Cell Biol. 2001;79:132–140. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2001.00980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004;59:574–580. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes PJ, Shapiro SD, Pauwels RA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: molecular and cellular mechanisms. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:672–688. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00040703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amrani Y, Bronner C. Tumor necrosis factor alpha potentiates the increase in cytosolic free calcium induced by bradykinin in guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle cells. C R Acad Sci. 1993;III(316):1489–1494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amrani Y, Martinet N, Bronner C. Potentiation by tumour necrosis factor-alpha of calcium signals induced by bradykinin and carbachol in human tracheal smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:4–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sathish V, Abcejo AJ, VanOosten SK, Thompson MA, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM. Caveolin-1 in cytokine-induced enhancement of intracellular Ca2+ in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:L607–614. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00019.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sathish V, Thompson MA, Bailey JP, Pabelick CM, Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Effect of proinflammatory cytokines on regulation of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ reuptake in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;297:L26–34. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00026.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sukkar MB, Hughes JM, Armour CL, Johnson PR. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha potentiates contraction of human bronchus in vitro. Respirology. 2001;6:199–203. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2001.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reynolds AM, Holmes MD, Scicchitano R. Cytokines enhance airway smooth muscle contractility in response to acetylcholine and neurokinin A. Respirology. 2000;5:153–160. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1843.2000.00240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen H, Tliba O, Van Besien CR, Panettieri RA, Jr., Amrani Y. TNF-[alpha] modulates murine tracheal rings responsiveness to G-protein-coupled receptor agonists and KCl. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:864–872. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00140.2003. discussion 863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Galione A, Lee HC, Busa WB. Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in sea urchin egg homogenates: modulation by cyclic ADP-ribose. Science. 1991;253:1143–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.1909457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kip SN, Smelter M, Iyanoye A, Chini EN, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM, Sieck GC. Agonist-induced cyclic ADP ribose production in airway smooth muscle. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;452:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howard M, Grimaldi JC, Bazan JF, Lund FE, Santos-Argumedo L, Parkhouse RM, Walseth TF, Lee HC. Formation and hydrolysis of cyclic ADP-ribose catalyzed by lymphocyte antigen CD38. Science. 1993;262:1056–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.8235624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White TA, Kannan MS, Walseth TF. Intracellular calcium signaling through the cADPR pathway is agonist specific in porcine airway smooth muscle. Faseb J. 2003;17:482–484. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0622fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuemmerle JF, Makhlouf GM. Agonist-stimulated cyclic ADP ribose. Endogenous modulator of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in intestinal longitudinal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25488–25494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuemmerle JF, Murthy KS, Makhlouf GM. Longitudinal smooth muscle of the mammalian intestine. A model for Ca2+ signaling by cADPR. Cell Biochem Biophys. 1998;28:31–44. doi: 10.1007/BF02738308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sieck GC, White TA, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM, Wylam ME, Prakash YS. Regulation of store-operated Ca2+ entry by CD38 in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L378–385. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00394.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson M, Barata da Silva H, Zielinska W, White TA, Bailey JP, Lund FE, Sieck GC, Chini EN. Role of CD38 in myometrial Ca2+ transients: modulation by progesterone. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E1142–1148. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00122.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ge ZD, Zhang DX, Chen YF, Yi FX, Zou AP, Campbell WB, Li PL. Cyclic ADP-ribose contributes to contraction and Ca2+ release by M1 muscarinic receptor activation in coronary arterial smooth muscle. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:28–36. doi: 10.1159/000068936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kannan MS, Fenton AM, Prakash YS, Sieck GC. Cyclic ADP-ribose stimulates sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release in porcine coronary artery smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1996;270:H801–806. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.2.H801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deshpande DA, Walseth TF, Panettieri RA, Kannan MS. CD38/cyclic ADP-ribose-mediated Ca2+ signaling contributes to airway smooth muscle hyper-responsiveness. FASEB J. 2003;17:452–454. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0450fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Prakash YS, Thompson MA, Vaa B, Matabdin I, Peterson TE, He T, Pabelick CM. Caveolins and intracellular calcium regulation in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293:L1118–1126. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00136.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prakash YS, Thompson MA, Pabelick CM. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in TNF-alpha modulation of Ca2+ in human airway smooth muscle. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;41:603–611. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0151OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sathish V, Abcejo AJ, Thompson MA, Sieck GC, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM. Caveolin-1 regulation of store-operated Ca2+ influx in human airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:470–478. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00090511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graeff RM, Walseth TF, Fryxell K, Branton WD, Lee HC. Enzymatic synthesis and characterizations of cyclic GDP-ribose. A procedure for distinguishing enzymes with ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30260–30267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ay B, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM, Sieck GC. Store-operated Ca2+ entry in porcine airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L909–917. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00317.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White TA, Xue A, Chini EN, Thompson M, Sieck GC, Wylam ME. Role of TRPC3 in Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Enhanced Calcium Influx in Human Airway Myocytes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;35:243–251. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0003OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sathish V, Yang B, Meuchel L, VanOosten S, Ryu A, Thompson MA, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM. Caveolin -1 and force regulation in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300:L920–929. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00322.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deshpande DA, White TA, Dogan S, Walseth TF, Panettieri RA, Kannan MS. CD38/cyclic ADP-ribose signaling: role in the regulation of calcium homeostasis in airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L773–788. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00217.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guedes AG, Jude JA, Paulin J, Kita H, Lund FE, Kannan MS. Role of CD38 in TNF-{alpha}-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L290–299. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00367.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guedes AG, Paulin J, Rivero-Nava L, Kita H, Lund FE, Kannan MS. CD38-deficient mice have reduced airway hyperresponsiveness following IL-13 challenge. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L1286–1293. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00187.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee HC, Aarhus R. Wide distribution of an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of cyclic ADP-ribose. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1164:68–74. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rusinko N, Lee HC. Widespread occurrence in animal tissues of an enzyme catalyzing the conversion of NAD+ into a cyclic metabolite with intracellular Ca2+-mobilizing activity. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:11725–11731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fukushi Y, Kato I, Takasawa S, Sasaki T, Ong BH, Sato M, Ohsaga A, Sato K, Shirato K, Okamoto H, Maruyama Y. Identification of cyclic ADP-ribose-dependent mechanisms in pancreatic muscarinic Ca2+ signaling using CD38 knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:649–655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004469200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okamoto H. The CD38-cyclic ADP-ribose signaling system in insulin secretion. Molecular and cellular biochemistry. 1999;193:115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yusufi AN, Cheng J, Thompson MA, Dousa TP, Warner GM, Walker HJ, Grande JP. cADP-ribose/ryanodine channel/Ca2+-release signal transduction pathway in mesangial cells. American journal of physiology. Renal physiology. 2001;281:F91–F102. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.1.F91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barata H, Thompson M, Zielinska W, Han YS, Mantilla CB, Prakash YS, Feitoza S, Sieck G, Chini EN. The role of cyclic-ADP-ribose-signaling pathway in oxytocin-induced Ca2+ transients in human myometrium cells. Endocrinology. 2004;145:881–889. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White TA, Johnson S, Walseth TF, Lee HC, Graeff RM, Munshi CB, Prakash YS, Sieck GC, Kannan MS. Subcellular localization of cyclic ADP-ribosyl cyclase and cyclic ADP-ribose hydrolase activities in porcine airway smooth muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1498:64–71. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(00)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Broide DH, Lotz M, Cuomo AJ, Coburn DA, Federman EC, Wasserman SI. Cytokines in symptomatic asthma airways. Journal of Allergy & Clinical Immunology. 1992;89:958–967. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(92)90218-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kips JC, Tavernier J, Pauwels RA. Tumor necrosis factor causes bronchial hyperresponsiveness in rats. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;145:332–336. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/145.2_Pt_1.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amrani Y, Krymskaya V, Maki C, Panettieri RA., Jr. Mechanisms underlying TNF-alpha effects on agonist-mediated calcium homeostasis in human airway smooth muscle cells. American journal of physiology. 1997;273:L1020–1028. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.273.5.L1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hunter I, Nixon GF. Spatial compartmentalization of TNFR1-dependent signaling pathways in human airway smooth muscle cells: lipid rafts are essential for TNF-alpha -mediated activation of RhoA but dispensable for the activation of the NF-kappa B and MAPK pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34705–34715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605738200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kang BN, Deshpande DA, Tirumurugaan KG, Panettieri RA, Walseth TF, Kannan MS. Adenoviral mediated anti-sense CD38 attenuates TNF-alpha-induced changes in calcium homeostasis of human airway smooth muscle cells. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:799–804. doi: 10.1139/y05-081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gosens R, Stelmack GL, Dueck G, McNeill KD, Yamasaki A, Gerthoffer WT, Unruh H, Gounni AS, Zaagsma J, Halayko AJ. Role of caveolin-1 in p42/p44 MAP kinase activation and proliferation of human airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L523–534. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halayko AJ, Stelmack GL. The association of caveolae, actin, and the dystrophinglycoprotein complex: a role in smooth muscle phenotype and function? Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:877–891. doi: 10.1139/y05-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Darby PJ, Kwan CY, Daniel EE. Caveolae from canine airway smooth muscle contain the necessary components for a role in Ca2+ handling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;279:L1226–1235. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.6.L1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McMahon KA, Zajicek H, Li WP, Peyton MJ, Minna JD, Hernandez VJ, Luby-Phelps K, Anderson RG. SRBC/cavin-3 is a caveolin adapter protein that regulates caveolae function. The EMBO journal. 2009;28:1001–1015. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]