Abstract

It is widely accepted that many social and health problems have underlying behavioral causes. Because these problems are rooted in human behavior, solutions to deal with them also lie in human behavior. This paper examines ways of integrating customer engagement in social programs to influence and initiate behavior change effectively with a special focus on youth. This work followed a theoretical deduction by use of a literature review. Social marketing places emphasis on behavior change, and one of the key challenges for social marketers is to ensure a perceived value for customers in taking up and maintaining positive behavior. If perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, and values influence behavior, then the central focus should be on the youth. Integrating youth is a prerequisite for effective social marketing programs and ultimately behavioral change. This approach will pave the way for effective brand positioning and brand loyalty in social marketing which has been lacking and requires more attention from researchers and policymakers. This paper outlines theoretical developments in social marketing that will increase the effectiveness of social marketing programs overall. Existing social marketing literature typically focuses on social marketing interventions and behavioral change. This paper uses customer engagement within a social marketing context so that social marketing programs are perceived as brands to which youth can relate.

Keywords: social marketing, customer engagement, behavioral influence, change, youth

Introduction

Youth often make decisions and choices which are detrimental to their health and to society at large. Policymakers, along with commercial and noncommercial organizations, use social marketing to address health and social problems, especially in areas where educational and legal interventions have failed.1 Because social marketing focuses on influencing behavioral change, there has been a dramatic increase in its application.2 Social marketing has been used to deal with obesity, tobacco prevention and cessation, family planning, promoting safe sex, waste management, and environment management.3–5

Andreasen6 discussed the origins of social marketing extensively, and the transformations and challenges the domain has faced. In suggesting how the discipline could develop further, he highlights two key challenges, ie, identifying potential triggers between contemplation and action, and maintenance of behavior. A review of social marketing effectiveness based on 54 interventions7 found evidence that interventions developed on the basis of social marketing criteria4 can be effective. However, that review noted that interventions to prevent youth smoking and alcohol and illicit drug use had significant positive effects in the short term but that these effects were not consistent in the medium to long term, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Effectiveness of social marketing interventions. Adapted from data presented in Stead et al.7

Why is it difficult to achieve long-term behavioral change? Why is it difficult to convert intentions into actual behaviors? Because the premise of social marketing is based on applying commercial marketing techniques, this paper examines the current trend in commercial marketing, ie, customer engagement, and assesses its applicability in social marketing. Suggestions for future directions in this discipline with a theoretical customer engagement framework are proposed in an attempt to engage customers for initial and sustainable behavioral change. As discussed in this paper, customer engagement sheds light on the “black box” that exists between intentions and behavior.

Behavior change through social marketing

There are three common approaches to behavior change, ie, education, marketing, and legislation.8 Education focuses on raising awareness but does not offer rewards or punishment, marketing attempts to influence behavior by offering incentives and/or disincentives in an environment of voluntary exchange, and legislation uses coercion to influence behavior. Because marketing offers an incentive and is voluntary, it has the ability to influence behavior effectively in the long term.

In 1951, when Wiebe9 asked “Can brotherhood be sold like soap?” he paved the way for researchers and practitioners to adapt commercial marketing tools to solve health and social problems. The principles and practices of social marketing are being successfully applied to many health programs.10 The definition proposed by Kotler and Zaltman11 focused more on ideas than on attitudes and behavior. Bartels12 shifted the focus from “economic” behavior to “social” behavior to broaden the scope of marketing. Andreasen identified social marketing as the application of marketing techniques to influence human behavior in a manner that is beneficial to the community, and proposed the following definition of social marketing: “The application of commercial marketing technologies to the analysis, planning, execution and evaluation of programs designed to influence the voluntary behavior of target audiences in order to improve their personal welfare and that of society.”13

This definition emphasizes that the core of social marketing is to promote behavioral change. The key dimensions to this are exchange, commercial marketing strategies, and voluntary change. MacFadyen et al14 perceived social marketing as having an influence on individual behavior, and further suggested that it could be used to change the behavior of groups and organizations and to target broader environmental influences on behavior. The National Social Marketing Centre15 defines social marketing as “the systematic application of marketing alongside other concepts and techniques to achieve specific behavioral goals, for social or public good”. With the growing debate over definitions in social marketing, Andreasen4 called for social marketers to focus more on designing effective social marketing programs. He developed the following six benchmarks by which a social marketing program can be developed and assessed: use of behavioral change is the benchmark; consistent use of audience research when developing, testing, and monitoring an intervention; careful segmentation of the target audience; clear motivation that influences the target audience to change or modify behavior; use of the traditional four “Ps” in the social marketing strategy; and awareness of competitor products that might impede the desired behavior.

The key purpose of social marketing is to benefit individuals, who are the target of any campaign, not the organizations responsible for the campaign. Social marketing focuses on the target audience, which has a primary role in the process.16 The planning process in social marketing takes this consumer focus into account by addressing the elements of the marketing mix. The “marketing mix”, ie, the four “Ps” first described by McCarthy in 1960 as “product, price, place and promotion”,17 demands that managers make choices concerning the type and number of products to produce, the number and type of distribution channels for those products, and the positioning of the products with respect to substitutes and similar offerings from competitors.18

These four Ps are often used in social marketing, such as demarketing of tobacco to discourage its use. Kotler and Levy define demarketing as “that aspect of marketing that deals with discouraging customers in general or a certain class of customers in particular on either a temporary or permanent basis”.19 In the social marketing context, the aim of demarketing is to deflate demand by discouraging consumption or use of products that pose a serious health risk.20 This is implemented using various demarketing strategies formulated around the four “Ps”, such as tobacco price increases,21 advertising bans,22 and smoking bans.23 Successful marketing programs use a differentiated marketing mix to target specific segments of the general population. The emphasis lies in the target markets being attractive due to their uniqueness and likelihood of purchasing a particular product. A distinction between the traditional four “Ps” of marketing and the four “Ps” of demarketing was made by Shiu et al.24 To assess the implications of social marketing strategies, it is crucial to examine the behavior of consumers carefully.

Theory of reasoned action

In an attempt to articulate a “cumulative body of knowledge in the attitude area”25 that would provide a clear distinction between beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors, Fishbein and Ajzen developed the theory of reasoned action, which has been used by many researchers to predict an individual’s intentions or behavior,26 but it does have limitations.27 The main criticism of the theory of reasoned action is that it fails to account for behaviors associated with incomplete volitional control.28

Theory of planned behavior

The theory of planned behavior put forward by Ajzen29 is an extension of Fishbein and Ajzen’s theory of reasoned action. The central construct of this theory is still intention, with the inclusion of “perceived behavioral control” as a further construct. Burton30 points out that, with the inclusion of the perceived behavioral control construct, this model enables measurement of the extent to which an individual believes the outcomes of behavior can be controlled. The theory of planned behavior suggests the use of attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control to understand beliefs and thus predict behavior.

Health belief model

Developed in the 1950s, the health belief model suggests that health behavior is a function of individual sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge, and attitudes.31 The limitation of the health belief model is that it does not focus on factors enabling and reinforcing human behavior, and these factors become increasingly important when the model is used to explain and predict more complex lifestyle behaviors that need to be maintained over a lifetime, just like the theory of reasoned action, the theory of planned behavior, and the “precede-proceed model”.32 Nevertheless, the health belief model has been used widely in the public health literature, almost replacing the transtheoretical model of stages of change developed by Prochaska and Velicer,33 focusing on the stages of: precontemplation, ie, no intention to take action within the next 6 months; contemplation, ie, intention to take action within the next 6 months; preparation, ie, intention to take action within the next 30 days and some behavioral steps have been taken; action, ie, overt behavior has been changed for less than 6 months; and maintenance, ie, overt behavior has been changed for more than 6 months.

Social cognitive theory

The social cognitive (learning) theory states that new behaviors are learned either by modeling the behavior of others or by direct experience. Social learning theory looks at human behavior as a continuous interaction between cognitive, behavioral, and environmental determinants.34 Successful implementation of intervention strategies needs enlistment of the help of these subgroups and to modify the norms of this network to support positive changes in behavior.35

Diffusion of innovation theory

Rogers36 describes the diffusion of power theory as the process by which an idea is disseminated throughout a community. This theory has four essential elements, ie, innovation of an idea or concept; communication of the idea to a target audience; use of a social system to implement the idea; and allowing ample time for the idea to be cemented in the long term. The community needs to be exposed to a new idea, which takes place within a social network or through the media, and this will determine the rate at which people adopt a new behavior over time.37 When beneficial beliefs for prevention are instilled and widely held within an individual’s immediate social network, behavior is more likely to be consistent with perceived social norms.38 Both the social influence model39 and social network theory40 suggest that social behavior should be understood not as an individual phenomenon but rather in the context of relationships, with a network of people that act as a reference group and sanction behavior, and that this is key to understanding individual risk-taking behavior.41 In other words, social norms are best understood at the level of social networks. Social theories and models see individual behaviors as embedded in the social and cultural context of the target audience. Levy and Zaltman42 identified three levels in society at which social change might occur, ie, the micro level (individual), the group level (organization), and the macro level (society).

This review of social marketing and theories about behavioral change highlights that social marketing has emphasized both implicitly and explicitly a need for relationships. In relationship marketing, Morgan and Hunt43 discussed this as a network paradigm, which was subsequently adapted by Hastings5 to include a relational approach to social marketing. Therefore, social marketing is a process that works upstream, downstream, and midstream in the context of a holistic system of relationships.15 Can a general theory of change effectively provide a framework for behavior change as societies and individuals evolve?

Post-modernism

Post-modern theorists, eg, Lyotard,44 conceptualize modernity as an historical period in which, despite the world being understood as complex, perceptions were organized by totalizing theoretical systems focused on predictability, objectivity, and scientific progress. Post-modern knowledge is comprised of small and multiple narratives about a multiple world.45 Therefore, the argument is that it is not possible to describe the world through scientific discourses unified around a meta-language. Post-modernists view today’s world as fragmented, complex, and unpredictable. Venkatesh46 discussed the characteristics of post-modernity, ie, disappearance of continuity, unity, purpose, and commitment, and the emergence of fragmentation and resistance.

Beck et al47 disagree about the world being fragmented, observing that society will always form social cohesion in action. Individuals will change their values and social bonds according to their own perceptions about risks in a contemporary world, and individuals are capable of recognizing the social conditions of their existence. Goubman48 identifies this as the triumph of formal rationality and a calculative approach towards the universe, and the alliance between science and technology is seen as the main tool for comprehension of the universe. This is the central process of transition from modernity to post-modernity. Kellner49 suggests that we are in an interregnum between an aging modern and an emerging post-modern era. There are also claims that post-modernism has already occurred, equating it with an earthquake and we are now living with the aftershocks in a world that is forever changed.50

This paper is based on the notion that we are in a stage of transition. Hence the notion of individuals having a fixed set of values will change to one of each individual creating their own personal and flexible hierarchy out of the values available in their social and cultural settings.51 Rokeach defines a set of values in this context as an “enduring belief that a specific mode of conduct or end-state of existence is personally or socially preferable to an opposite or converse mode of conduct or end-state of existence”.52 Values influence an individual’s behavior and, as values change, so does behavior.

Firat and Venkatesh53 describe pastiche as an attitude expressed in the form of lack of emotional bonds and commitment by individuals. Schizophrenia is referred to as a lack of synchronicity between an individual’s identity and their experiences, resulting in materialistic consumption. This creates a scenario where an individual’s values are in conflict with societal values, which creates a dilemma for policymakers. The consequences of this conflict in values are discussed by Firat and Venkatesh,53 who categorize postmodern culture as hyperreality, fragmentation, reversal of consumption and production, decentering of the subject, and paradoxical juxtaposition of opposites, all of which create a loss of commitment. The gap between societal and individual value systems poses challenges for individual identity.

Bellah et al argues that “We need to recognize that it is only in relation to society that the individual can fulfill himself and that if the break with society is too radical, life has no meaning at all”.54 Therefore, individuals can only achieve genuine recognition of individuality via others. Hence, despite differences in ideology, an individual still depends on society. This calls for pluralism, which is the acceptance of differences.55 Acceptance of differences creates an environment conducive to social order, which is interrelated with overall economic order. Sherry56 identified this, and called for tolerance and recognition of differences. This can only be achieved by dialog and interaction.

Creation of value

The impact of postmodernism and its interplay with marketing has been discussed by previous researchers.53,57,58 Post-modernism is a call for marketing to deepen its paradigm and place an emphasis on consumers as individuals and not as segments. The discipline has been going through changes over the years from a transaction focus to a relational focus.59 To address consumer attributions to value in the post-modern world, the customer is seen as the main driver of value creation.60,61 Traditional marketing has failed to place customers first,62 and relationship marketing is needed for the transformation towards genuine customer involvement to increase both the effectiveness and efficiency of marketing.63,64

Relationship marketing

Gronroos65 developed several new concepts in service marketing, which were later incorporated as part of the Nordic School of Services. The central focus was on relationship marketing. Relationship marketing has been viewed as buyer-seller encounters that accumulate over time, with opportunities to transform individual and discrete transactions into relational partnerships.66 Tzokas and Saren defined relationship marketing as “the process of planning, developing and nurturing a relationship climate that will promote a dialogue between a firm and its customers which aims to imbue an understanding, confidence and respect of each others’ capabilities and concerns when enacting their role in the market place and in society”.67 The concept of dialog has been captured by this definition of relationship marketing, which creates a perception about value and quality.

Quality perceived by consumers

Other researchers68,69 have discussed customer-perceived quality as a function of customer perception of two dimensions, ie, what the customer receives and the impact of various interactions the customer has with the marketing body. In the interaction process, these are known as technical quality and functional quality, respectively.70 Technical quality is dominant in transaction marketing. Relationship marketing encompasses both quality dimensions in an attempt to provide customers with added value. Morgan and Hunt43 emphasize trust and commitment as being crucial to the relationship to add value for customers.

Trust

Discussions on trust have received a great deal of attention in organizational behavior studies,71 in social psychology,72 sociology,73 and in economics.74 Trust has been conceptualized as a willingness to rely on an exchange partner in whom one has confidence,75 and according to Morgan and Hunt,43 exists when one party has confidence in an exchange partner’s reliability and integrity. Furthermore, trust directly influences relationship commitment.43

Commitment

Commitment is considered to be central to all relational exchanges between the various protagonists in commercial marketing.43 Moorman et al define commitment as “an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship”.75 Morgan and Hunt’s43 theory of trust and commitment can be expanded further by including satisfaction as a key concept.76

Satisfaction

De Wulf and Odekerken-Schroder76 define relationship satisfaction as a consumer’s affective state resulting from an overall appraisal of his or her relationship with the retailer. Satisfaction has become the mantra for corporate success.77 In the academic literature, satisfaction has been conceptualized as a post-consumption cognitive process.78,79 Satisfaction alone does not measure the depth of consumer responses and reactions to consumption, and should not be relied on exclusively as a proxy for loyalty.80 Bowden81 called further for a distinction between new and loyal customers. There is a need to focus beyond post-consumption and explore ways of integrating consumers in delivering value, which will influence attitude and behavior.

The drivers of relationship marketing are companies which, in the context of social marketing, are social marketing organizations. Patterson et al82 discuss multicomponent social marketing interventions, such as community, school, and family involvement, which have long-term effects, underscoring the importance of integrating all stakeholders. To achieve behavioral change, there is a need to focus on upstream and midstream stakeholders in social marketing. As conflict and disjointedness between societal and individual value systems continues, there is a need to integrate all protagonists in a relationship for the betterment of both society and the individual.

Relationship marketers offer customers value-adding benefits that are not readily available elsewhere, which creates a strong foundation for maintaining and enhancing relationships. In the case of social marketing, the challenge is to portray the benefit of giving up socially undesirable behaviors, such as smoking, alcohol, and drug abuse, which often leads social marketers to resort to scare tactics, which can change a behavior temporarily, eg, fear-based antismoking advertisements, but long-term behavioral change requires commitment and loyalty. Achterberg et al,83 in an empirical study, identified that type of involvement rather than advertising appeal increases brand loyalty. Because individuals project themselves through brand association, a social marketing intervention needs to create its own brand, not by scare tactics but by customer involvement.

Another issue is that commitment to the relationship is pivotal to social marketing, and consumer behavior change will not be sustainable without it. Because the post-modern consumer experiences distrust and loss of commitment, there is a challenge in relationship marketing to ensure trust and commitment is embedded between consumers and stakeholders. However, social marketing organizations are still drivers of trust and commitment.

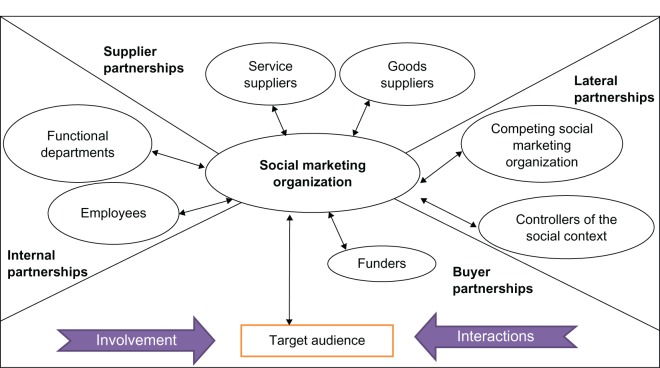

How can customers be involved in social marketing programs so that satisfaction, trust, and commitment can lead to actual behaviors and not just intentions? The solution lies in customer engagement. This represents a dilemma, because the multirelationship model of social marketing described by Hastings5 places the focus once again on social marketing organizations rather than on customers. Addressing this gap, this paper focuses on the central tenet of the multirelationship model of social marketing to consumers, as emphasized by Morgan and Hunt (see Figure 2).43

Figure 2.

Multirelationship model of social marketing.43

Adapted from Morgan and Hunt, The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J Marketing. 1994;58(3):20–38. With permission from the American Marketing Association, Copyright © 1994.

Customer engagement

An examination of other such mechanisms led to a focus on the customer engagement concept, which may be a superior predictor of customer loyalty relative to traditionally used marketing constructs.84,85 The concept of engagement has its origins traced back to psychology and organizational behavior disciplines.86,87 In organizational behavior, the term “employee engagement” has been used as a means to explore and explain organizational commitment and citizenship behavior, and subsequently as a predictor of financial performance.88

Engagement has been found to generate a number of potentially positive consequences at both the organizational and individual levels including attitudes, intentions, and behaviors, such as job satisfaction, low absenteeism, high organizational commitment, superior customer-related performance, and customer evaluations.84–88 In the marketing discipline, the concept is typically applied as “customer engagement”,84,85 reflecting the relevant individual and/or context-specific levels of engagement of customers with particular objects, such as brands,88 products, or organizations.85 Customer engagement is thus crucial to explaining and/or predicting customer experience, perceived value, and/or loyalty outcomes. Bowden defines customer engagement as “a psychological process that models the underlying mechanisms by which customer loyalty forms for new customers of a service brand as well as the mechanisms by which loyalty may be maintained for repeat purchase customers of a service brand”.81

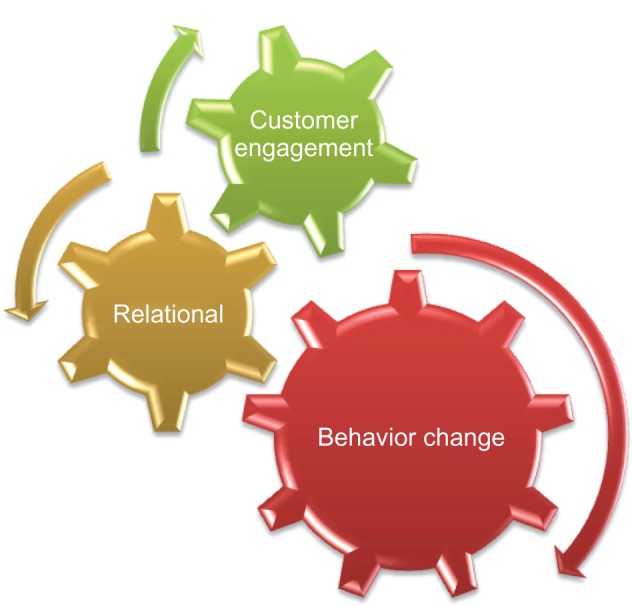

Current research focuses on customer engagement behavior which also encompasses customer cocreation.90 Trust, commitment, and satisfaction are customer attitudes, which are also motivational drivers for consumers to focus on beyond purchase and consumption. Therefore, customer engagement is seen from a behavioral perspective. Customer engagement also allows for the expression of a customer’s preferred contextual self.85 This addresses the fragmentation between the individual and society in postmodern culture. Andreasen4 has discussed the need for the target audience to be involved in predesign, design, implementation, and evaluation of social programs. However, there has been a surprising oversight by social markets in integrating customers theoretically into social marketing programs, even though reviews of social marketing highlight the importance of focusing on customers for behavior change. Hastings5 had made contributions in adding the relational paradigm in social marketing, and Russell-Bennett et al79 have discussed a value creation model for governmental social marketing activities. Their paper suggests integrating customer engagement in social marketing, as shown in Figure 3, for further deepening of the social marketing domain.

Figure 3.

Customer engagement in social marketing.

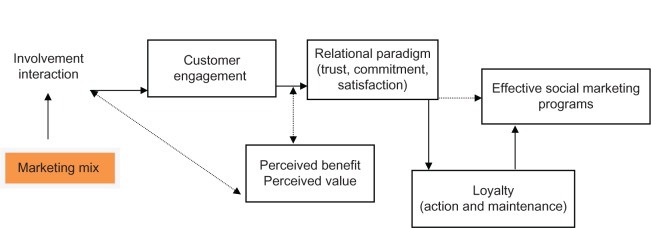

For customers to perceive value and benefit in social marketing interventions and to establish long-term relationships, there is a need to engage customers in creating value to maintain loyalty. The relationships built with different stakeholders through interactions motivate customers to be involved in the design and implementation of effective social marketing programs. Involvement and interaction allow room for customers to be cocreators in social marketing programs, which customers can then identify with (trust) and commit to (moving from intentions to actual behavior). Social marketing is still the umbrella for behavioral change. Behavioral change is regarded as a subcategory of a larger concept, ie, behavioral influence.13 Within effective social marketing programs, there is a need to create perceived value/benefit of behavioral change in the minds of customers. This will only happen if there is an environment of satisfaction, trust, and commitment, which needs customer engagement, ie, involvement and interactions. Trust, commitment, and satisfaction are antecedents to creating positive perceived value/benefit, and are also outcomes of positive perceived value/benefit, which then leads to sustainable behavioral change. The move to relational and engagement paradigms in social marketing does not mean that social marketers should ignore the important role played by the traditional marketing mix in designing effective social marketing programs. Segmentation of the target audience, in this case youth, is also critical, as proposed in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Proposed framework for effective social marketing programs.

Conclusion

Social marketing as a domain started when Wiebe9 questioned “why brotherhood can’t be sold like soap?” The social marketing domain has been dominated by interventions and objectives concerning behavioral change,5 mostly concentrating on the marketing mix. One oversight by many social marketers has been that when Wiebe posed the above question, the focus shifted towards “soap”, ie, commercial marketing, instead of broadening the focus to include the “brotherhood” aspects in social marketing. The Oxford Dictionary89 defines brotherhood as “the feeling of kinship with and closeness to a group of people or all people who are linked with a common interest or association”. This social network is evident amongst youth, who see groups as a reflection of their identity.

The premise of social marketing is not only based on adapting commercial marketing techniques but also on relationships. There are sets of values and perceptions in the contemporary world to create positive perceived value in the minds of youth through meaningful and long-term relationships (trust, commitment, and satisfaction), and youth need to be engaged right at the beginning (through involvement and interactions) for sustainable behavioral change. Trust, commitment, and satisfaction are not only consequences of customer engagement but are also antecedents of customer engagement in the long term. The absence of customer engagement undermines social marketing programs which have their foundations in youth. If behavioral change is the ultimate goal, then the process of building relationships has to be incorporated into social marketing. To build this relationship, youth in social marketing programs should be seen as customers and partners in cocreating value. This allows for both consumer-oriented and stakeholder-oriented outcomes to be achieved. Customer engagement should be seen as an added dimension in effective social marketing programs.

Perceived value and perceived benefit of individuals is a manifestation of self image. Because the postmodern customer is going through a transformation of value systems, there is a greater need for empowerment and capacity building. Empowerment refers to the ability of people to gain understanding and control over personal, social, economic, and political forces in order to take action to improve their life situations.90 With empowerment, one can bridge the gap between society and the individual. The process of empowerment, dialog, interaction, and involvement is difficult,5 but it can be achieved by engaging customers throughout planning, design, implementation, and evaluation of social marketing programs, especially with the involvement of social media. This paper attempts to provide a perspective for integrating customer engagement into a social marketing program. Future research can focus on testing the framework empirically and deepening this concept in social marketing.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Diamond W, Oppenheim MR. Sources for special topics: social marketing, nonprofit organisations, service marketing and legal/ethical issues. J Bus Finance Librarianship. 2004;9(4):287–299. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gordon R, McDermott L, Stead M, Angus K. The effectiveness of social marketing interventions for health improvement: what’s the evidence? Public Health. 2006;120(12):1133–1139. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kotler P, Roberto N, Lee N. Social Marketing: Improving the Quality of Life. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andreasen AR. Marketing social marketing in the social change marketplace. J Public Policy Marketing. 2002;21(1):3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hastings G. Relational paradigms in social marketing. J Macromarketing. 2003;23(1):6–15. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreasen AR. The life trajectory of social marketing: some implications. Marketing Theory. 2003;3(3):293–303. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stead M, Gordon R, Angus K, McDermott L. A systematic review of social marketing effectiveness. Health Educ. 2007;107(2):126–191. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rothschild ML. Carrots, sticks and promises: a conceptual framework for the management of public health and social issues behaviours. J Marketing. 1999;63:24–37. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiebe GD. Merchandising commodities and citizenship on television. Public Opin Q. 15:1951–1952. 679–691. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novelli WD. Applying social marketing to health promotion and disease prevention. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kotler P, Zaltman G. Social marketing: an approach to planned social change. J Marketing. 1971;35:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartels R. The identity crisis in marketing. J Marketing. 1974;38(4):73–76. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andreasen A. Marketing Social Change: Changing Behavior to Promote Health, Social Development, and the Environment. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.MacFadyen L, Stead M, Hastings GB. Social marketing. In: Baker MJ, editor. The Marketing Book. 5th ed. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Social Marketing Centre . Social Marketing Works: A Powerful and Adaptable Approach for Achieving and Sustaining Positive Behaviour. London, UK: National Consumer Council; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weinreich NK. Hands-On Social Marketing: A Step-By-Step Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterschoot W, Van den Bulte C. The 4P classification of the marketing mix revisited. J Marketing. 1992;56(4):83–93. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porter ME. Competitive Strategy: Techniques for Analyzing Industries and Competitors. New York: Free Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kotler P, Levy S. Broadening the concept of marketing. J Marketing. 1969;33(1):10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Comm CL. Demarketing products which may pose health risks: an example of the tobacco industry. Health Mark Q. 1997;15(1):95–102. doi: 10.1300/j026v15n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andrews RL, Franke GR. The determinants of cigarette consumption: a meta-analysis. J Public Policy Marketing. 1981;10:81–100. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saffer H, Chaloupka F. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. J Health Econ. 2000;9(6):1117–1137. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(00)00054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wall AP. Government demarketing: different approaches and mixed messages. Eur Marketing. 2005;39(5–6):421–427. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiu E, Hassan L, Walsh G. Demarketing tobacco through governmental policies: the 4Ps revisited. J Bus Res. 2008;62:269–278. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madden MJ, Ellen PS, Ajzen I. A comparison of the theory of planned behavior and the theory of reasoned action. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1992;18(1):3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheppard BH, Hartwick J, Warshaw PR. The theory of reasoned action: a meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. J Consumer Res. 1998;15:325–343. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organiz Behav Hum Decision Proc. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ajzen I. From intentions to actions: a theory of planned behavior. In: Kuhl J, Beckmann J, editors. Springer Series in Social Psychology. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burton RJ. Reconceptualising the behavioural approach in agricultural studies: a socio-psychological perspective. J Rural Stud. 2004;20(3):359–371. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stretcher VJ, Rosenstock IM. The health belief model. In: Glanz L, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, editors. Health Behaviour and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mullen PD, Hersey J, Iverson DC. Health behavior models compared. Soc Sci Med. 1987;24:973–981. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(87)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF. The trans-theoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997;12(1):38–48. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bandura A. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kelly JA. Community-level interventions are needed to prevent new HIV infections. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:299–301. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers EM. Diffusion of Innovations. New York: Free Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kegeles SM, Robert BH, Thomas JC. The Mpowerment Project: a community-level HIV prevention intervention for young gay and bisexual men. Am J Public Health. 1996;86:1129–1136. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.8_pt_1.1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelly J. Changing HIV Risk Behavior: Practical Strategies. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Howard M, McCabe J. Helping teenagers postpone sexual involvement. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22(1):21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morris M. Sexual networks and HIV. AIDS. 1997;11(Suppl A):S209–S216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Auerbach DM, Darrow WW, Jaffe HW, Curran JW. Cluster of cases of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Patients linked by sexual contact. Am J Med. 1984;76:487–492. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levy SJ, Zaltman G. Marketing, Society and Conflict. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan RM, Hunt SD. The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J Marketing. 1994;58(3):20–38. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyotard JF. The Postmodern Condition. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Giddens A. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Venkatesh A. Modernity and postmodernity: a synthesis or antithesis? In: Childers T, editor. Proceedings, AMA Winter Educators Conference. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association; 1989. pp. 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beck U, Giddens A, Lash S. Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goubman B. Postmodernity as the climax of modernity: horizons of the cultural future; Twentieth World Congress of Philosophy; August 10–15, 1998; Boston, MA. [Accessed October 6, 2011]. Available from: http://www.bu.edu/wcp/Papers/Cult/CultGoub.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kellner D. From 9/11 to Terror War: Dangers of the Bush Legacy. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wallace S. About postmodernism [Internet] 2003. [Accessed on October 11, 2011]. Available from: http://www.freewaybr.com/usfs.htm.

- 51.Woodall T. Acad Marketing Sci Rev [serial on the Internet] 2003. [Accessed October 6, 2011]. Conceptualizing value for the customer: an attributional, structural and dispositional analysis. Available from: http://www.amsreview.org/articles/woodall12-2003.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rokeach M. The Nature of Human Value. New York: The Free Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Firat AF, Venkatesh A. Postmodernity: the age of marketing. Int J Res Marketing. 1993;10(3):227–249. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bellah R, Madsen R, Sullivan W, Swidler A, Tipton S. Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Raaji WF. Postmodern consumption. J Econom Psychol. 1993;14:541–563. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sherry JF. Postmodern alternatives: the interpretive turn in consumer research. In: Kassarjian H, Robertson T, editors. Handbook of Consumer Theory and Research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1991. pp. 548–591. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Firat AF. The consumer in postmodernity. In: Holman RH, Solomon MR, editors. Advances in Consumer Research. 18. Association for Consumer Research; 1990. pp. 70–76. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown S. Postmodern marketing? Eur J Marketing. 1993;27(4):19–34. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Webster FE. The changing role of marketing in the corporation. J Marketing. 1992;56:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gummesson E. Relationship marketing as a paradigm shift: some conclusions from the 30R approach. Manag Decis. 1997;35(3–4):267–273. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gummesson E. Qualitative Methods in Management Research. 2nd (revised) ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Desmond J. Marketing and the war machine. Marketing Intell Plan. 1997;15(7):338–351. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sheth JN, Atul P. Relationship Marketing in Consumer Markets: Antecedents and Consequences. J Acad Marketing Sci. 1995;23(4):255–271. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gordon F. The role of commitment in service relationships. In: Gundlach G, Murphy P, editors. AMA Educators’ Proceedings: Enhancing Knowledge Development in Marketing. Chicago, IL: AMA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gronroos C. From marketing mix to relationship marketing: towards a paradigm shift in marketing. Manag Decis. 1997;35(3–4):322–340. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Czepiel JA. Service encounters and service relationships: implications for research. J Bus Res. 1990;20(1):13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tzokas N, Saren M. Building relationship platforms in consumer markets: a value chain approach. J Strateg Marketing. 1997;5(2):105–120. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lehtinen U. Our present state of ignorance in relationship marketing. Asia-Austral Marketing J. 1996;4(1):43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gummesson E. Relationship marketing and imagery organizations: a synthesis. Eur J Marketing. 1996;30(2):31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gronroos C. Relationship marketing: strategic and tactical implications. Manag Decis. 1996;34(3):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Rousseau DM, Sitkin SB, Burt RS, Camerer C. Not so different after all: a cross discipline view of trust. Acad Manag Rev. 1998;23:393–404. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lewicki R, Bunker B. Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships. In: Kramer R, Tyler T, editors. Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lewis JD, Weigert A. Trust as a social reality. Soc Forces. 1985;63(4):967–985. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dasgupta P. Trust as a commodity. In: Gambetta D, editor. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Moorman C, Deshpande R, Zaltman G. Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. J Marketing. 1992;57(1):81–101. [Google Scholar]

- 76.De Wulf K, Odekerken-Schroder G. A critical review of theories underlying relationship marketing in the context of explaining consumer relationships. J Theor Soc Behav. 2001;31(1):73–102. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saks AM. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J Manag Psychol. 2006;21(7):600–619. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sprott D, Czellar S, Spangenberg E. The importance of a general measure of brand engagement on market behavior: Development and validation of a scale. J Marketing Res. 2009;46:92–104. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bennett R, undle-Thiele S. Customer satisfaction should not be the only goal. J Serv Marketing. 2004;187:514–523. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Oliver R. Whence customer loyalty? J Marketing. 1999;63(4):33–44. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bowden JL. The process of customer engagement: a conceptual framework. J Marketing Theor Pract. 2009;17(1):63–74. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Patterson P, Yu T, De Ruyter K. Understanding customer engagement in services; Proceedings of ANZMAC 2006 Conference; 2006 December 4–6; Brisbane, Australia. 2006. Advancing Theory, Maintaining Relevance. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Achterberg W, Pot AM, Kerkstra A, Ooms M. The effect of depression on social engagement in newly admitted Dutch nursing home residents. Gerontologist. 2003;43(2):213–218. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Saks AM. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J Manager Psychol. 2006;21(7):600–619. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Salanova M, Agut S, Peiro JM. Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: the mediation of service climate. J Appl Psychol. 2005;90(6):1217–1227. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Hayes TL. Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol. 2002;87(2):268–279. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.2.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sprott D, Czellar S, Spangenberg E. The importance of a general measure of brand engagement on market behavior: development and validation of a scale. J Marketing Res. 2009;46:92–104. [Google Scholar]

- 88.van Doorn J, Lemon KN, Mittal V, et al. Customer engagement behavior: theoretical foundations and research directions. J Serv Res. 2010;13(3):253–266. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Oxford English Dictionary . Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Israel B, Checkoway B, Schultz A, Zimmerman M. Health education and community empowerment: conceptualizing and measuring perceptions of individual, organizational and community control. Health Educ Q. 1994;21:149–170. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]