Women treated for cancer often experience issues related to sexual health and intimacy. The authors reviewed a contemporary understanding of sexual health of women and the impact of treatment on both sexual function and intimacy.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Cancer survivor, Gynecologic cancer, Sexual health, Quality of life

Abstract

As more and more people are successfully treated for and live longer with cancer, greater attention is being directed toward the survivorship needs of this population. Women treated for cancer often experience issues related to sexual health and intimacy, which are frequently cited as areas of concern, even among long-term survivors. Unfortunately, data suggest that providers infrequently discuss these issues. We reviewed a contemporary understanding of sexual health of women and the impact of treatment on both sexual function and intimacy. We also provide a review of the diagnosis using the newest classification put forth by the American Psychiatric Association in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, and potential treatments, including both endocrine and nonendocrine treatments that the general oncologist may be asked about when discussing sexual health with his or her patients.

Implications for Practice:

Sexual health is an important aspect of life and an area of concern consistently identified by women after treatment for cancer. Discussing sexual health should become a routine part of conversations with patients before, during, and especially after cancer treatment. Suggestions for communication and an overview of endocrine and nonendocrine treatment options are provided. Resources for patients and providers and the importance of working in a multidisciplinary way, whether it be with another clinician or a sexual health expert, to help patients with sexual health concerns is important as we seek to improve the sexual health of female cancer survivors.

Introduction

For patients diagnosed with cancer, survivorship starts at the time of diagnosis [1]. Fortunately, most patients can be expected to do quite well following diagnosis, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 70% across all tumor types [2]. Current estimates in the U.S. alone indicate that 64%, 40%, and 15% of cancer survivors are alive 5 years, 10 years, and 20 years or more, respectively, following diagnosis [3]. As a result, almost 13 million people in the U.S. and 30 million people globally are living beyond cancer [4].

Despite the data showing that most survivors have a good prognosis, current treatments can result in problems, which can extend for years after treatment. Of those most commonly cited by survivors are issues pertaining to sexual health [5]. In this review, we will discuss sexual health following the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. We will specifically concentrate on these issues as they relate to female cancer survivors; the approach to male sexual health after cancer differs substantially and is beyond the scope of this paper.

A Model for Female Sexual Health

An understanding of sexuality starts with the work of Masters and Johnson, who are credited with characterizing sexual response into four physiologic phases: (a) excitement, (b) plateau, (c) climax/orgasm, (d) resolution [6]. An appreciation of the psychological component of sexuality led to revision of the concept of sexual health in women by Kaplan and Horwith, who proposed a triphase archetype of desire, arousal, and orgasm [7]. Recognizing that female sexuality is often driven by psychological and psychosocial influences, Basson further elaborated on our understanding by incorporating intimacy as a driver for desire and sexual activity [8]. In this model, sexual health is viewed as a self-propagating circle in which the asexual female is motivated by a desire for intimacy, which triggers sexual stimuli. Once stimuli are fulfilled, sexual satisfaction fulfills desire and sets the cycle to repeat. Understanding that not all women are motivated by intimacy, Basson also proposed a “bypass” whereby sexual “hunger” may also provide the motivation for women to seek out fulfilling sexual encounters. An important aspect of the Basson model is the separation of sexuality and intimacy.

Although no conclusive data support one model over another, at least one study suggests that the Basson model is more accurate, particularly for women with sexual dysfunction [9]. Additional data to support the importance of intimacy come from various studies (predominantly in female survivors of breast cancer) that demonstrate the importance of emotional intimacy, including notions of marital affection and the bond between partners [10–13]. Indeed, for couples, the importance of intimacy for survivors was shown by Manne and Badr, who proposed the Relationship Intimacy Model, which characterizes the recovery from cancer treatment as multifactorial [13].

Finally, an additional model has been proposed to conceptualize stimuli and the way women respond to them. Characterized as the “sexual tipping point” by Perelman, it symbolizes the threshold at which a response is elicited [14]. The sexual tipping point is influenced by multiple aspects including both physical and psychological factors and attempts to stress the importance of paying attention to both of these factors with a multidisciplinary approach that integrates sex therapy with other interventions, including pharmaceuticals.

Sexual Health as a Survivorship Issue

For most people, sexual health is an important aspect of their lives, and there is no reason it should not apply for women following a diagnosis of cancer. Across multiple datasets, the incidence of sexual dysfunction ranges from 30% to 100% among female cancer survivors [5, 15]. Although studies show that the overall quality of life of survivors is quite good (especially in long-term survivors) [16–18], a significant proportion of patients remain at risk for persistent or worsening symptoms, including symptoms related to sexual health [19]. Although much of this work has been done in breast cancer survivors [19–23], emerging literature shows similar figures affected for survivors of gynecologic cancer [17, 24–26] and other cancer types [27–30].

With a growing recognition that sexual health concerns may persist after cancer treatment, the concept of sexual quality of life has been proposed by Beckjord and Campas as broadly encompassing sexual attractiveness, sexual interest, sexual participation, and sexual function [21]. In their study of women who were less than 6 months out from a diagnosis of breast cancer, they documented significant disruption in sexual quality of life that was influenced by treatments and the presence of emotional distress rather than age. Such data emphasize the importance of sexual health as a survivorship issue in women with cancer.

Sexual Health in Female Sexual Minorities

Although not as well studied, some data suggest that the predictors of sexual function after cancer do not differ by sexual orientation. This was shown in a study of women who have sex with women (WSW) and who have a history of breast cancer (n = 95) versus those without such history (n = 85) [31]. After controlling for case status, significant factors that explained sexual function in WSW included self-perceived sexual attractiveness (p < .0001) and whether urogenital symptoms were present (p < .0001). Among partnered women, an additional factor that emerged was the menopausal status; women who were pre- or perimenopausal had better sexual function than those who became menopausal (p < .00002).

Cancer Treatment and its Impact on Sexual Health

Female sexual dysfunction may present even before cancer is diagnosed, arise around the time of diagnosis, or result as a consequence of treatment. It is important that issues of sexual health be viewed in the overall context of women’s health because the issues that may be related to cancer often intersect with the normal sexual and reproductive health changes that occur as one ages [20]. Sexual health concerns that arise for a woman entering menopause at the time of a breast cancer diagnosis, for example, may be directly related to normal, age-related hormonal declines, the sequelae of breast cancer therapy, or a combination of both.

Surgery

Surgery can influence sexual health as a result of direct anatomic changes (e.g., mastectomy for breast cancer) or changes in the hormonal milieu as a result of treatment (e.g., oophorectomy). In addition, body image can be disrupted as a result of surgery, and this can affect sexual recovery.

For premenopausal women, oophorectomy, which is commonly performed for ovarian cancer, results in an immediate depletion of estrogen production and results in the early onset of menopausal symptoms, including vaginal thinning, compromised elasticity, atrophy, and dryness, all of which can affect the ability of women to engage in vaginal intercourse or achieve orgasm. In a small qualitative study involving eight women with ovarian cancer, Wilmoth et al. reported that, for them, treatment resulted in both mechanical and hormonal changes that were deemed “detrimental” to their sexuality [26].

Hysterectomy may also result in direct anatomic changes to the vaginal vault, including vaginal shortening and fibrosis, leading to long-term issues in sexual health [24, 25, 32]. The impact of surgery was shown in a study by Bergmark et al. that compared women without a history of cancer with women who had been treated for early stage cervical cancer [24]. Among those with cervical cancer, 36% and 52% of patients had surgery or surgery plus radiation therapy (RT), respectively. Compared with women without a history of cancer, patients treated with surgery only were associated with increased risks of vaginal dryness, vaginal shortness, and reduced vaginal elasticity. These effects did not appear to be affected by additional RT. For the entire cohort, women treated for cervical cancer experienced higher rates of sexual dissatisfaction, with dyspareunia persisting at 3 months and longer-term effects at 3 years, including difficulty with vaginal dryness and lowered sexual interest.

For women with breast cancer, the impacts of breast surgery on body image and self-esteem, both of which are important contributors to sexual health, are well characterized [22, 33, 34]. For young women, at least one study showed that alterations in body image were a significant negative predictor of sexual activity, regardless of surgery type and whether reconstruction was performed [22]. In addition, after controlling for prediagnosis sexual issues, a lower perception of sexual attractiveness was associated with greater sexual problems.

Beyond gynecologic and breast cancer, other surgical approaches have also been evaluated specifically as they affect sexual health; for example, both primary excision and mesorectal excision performed for rectal cancer result in a high rate of sexual dysfunction that approaches 60% [29, 30]. Additional data suggest that patients who underwent colectomy for colorectal cancer that required placement of an ostomy (in the past or presently) were at significant risk for sexual dysfunction and distress related to body image [27].

Medical Therapy

Most cytotoxic agents result in side effects, including constitutional symptoms (e.g., fatigue, weakness) and gastrointestinal toxicity (nausea and vomiting), that may limit a woman’s sexual interest or ability to become aroused. In younger women, chemotherapy is also a strong risk factor for amenorrhea and early menopause, which can directly affect sexual esteem and sexual function by inducing physical changes (vaginal dryness) and hormonal changes that, in addition to causing vasomotor symptoms, reduce libido. Chemotherapy also has a direct impact on body image, particularly with agents associated with alopecia, causing hair loss not only on the head but also loss of private and pubic hair [35]. Finally, chemotherapy may cause direct toxicities to the vagina and pelvis; for example, Krychman et al. reported a case of vaginal erythrodysesthesia related to liposomal doxorubicin [36].

Orally available endocrine therapies are commonly used to treat female malignancies, especially hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Emerging data suggest that although both selective estrogen receptor modulators (e.g., tamoxifen) and the aromatase inhibitors (AIs) may affect sexual function, the risk to sexual health may be greater with the AIs. This was shown in a study by Baumgart et al. in which more than 80 women taking tamoxifen or an AI were compared with women without breast cancer (controls) [37]. Among women taking an AI, significantly higher rates of sexual dysfunction were reported compared with both those taking tamoxifen and controls in the area of lubrication issues (74% vs. 40% and 42%, respectively), dyspareunia (57% vs. 31% and 21%), and global dissatisfaction with their sex lives (42% vs. 17.8% and 14%).

Among women taking an AI, significantly higher rates of sexual dysfunction were reported compared with both those taking tamoxifen and controls in the area of lubrication issues (74% vs. 40% and 42%, respectively), dyspareunia (57% vs. 31% and 21%), and global dissatisfaction with their sex lives (42% vs. 17.8% and 14%).

Radiation Therapy

For women treated with RT, both acute and long-term toxicities can inhibit sexual function, depending on the area treated. For women who receive RT for a genital or pelvic cancer, short-term toxicities include incontinence (of either urine or stool), irritation, and pain, all of which can dampen libido. Long-term side effects include fibrosis, which can cause vaginal stenosis or, at its most severe, agglutination of the vaginal vault, causing obliteration of the canal.

The long-term impact of pelvic RT on sexual function is also well documented. In one study, sexual functioning was evaluated among women with cervical cancer treated with RT alone, surgery plus RT, or chemotherapy alone [38]. RT resulted in similar sexual functioning at 6 months compared with radical hysterectomy alone, but at 1 year, RT was associated with reductions in sexual arousal and desire and increased rates of dyspareunia and reports of sexual discomfort.

Women who receive RT for breast cancer also are at risk for cosmetic changes, including acute erythema, discoloration, and skin breakdown, all of which can negatively affect body image. Long-term toxicities have also been described, including hyperpigmentation, breast edema, and breast fibrosis, with body image most often affected among younger women [39]. Finally, arm mobility may also be affected as a result of surgery and RT.

Barriers to Discussion: Patient Perspectives

Despite the importance of sexual health to women living beyond cancer, this issue is often unaddressed. There are probably numerous reasons patients do not bring up these issues first. One study of 500 adults found that patients reported fear of dismissal, perceived discomfort on the part of the physicians, and perceived lack of treatment options as reasons not to discuss these issues [40].

A survey that included approximately 26,000 men and women between the ages of 40 and 80 across 29 countries confirmed that physicians did not make it a common practice to discuss sexuality and intimacy and that this was a global phenomenon [41]. Within the U.S. alone, only 14% of patients reported being questioned by physicians about sexual issues within a time span of 3 years.

Part of this is explained by an assumption on the part of clinicians (explicit or presumed) that patients will bring it up to them without first being asked. Unfortunately, to expect patients to bring up a potentially sensitive issue is not realistic. In one study involving 878 women diagnosed with a gynecologic malignancy, only 3% brought sexual concerns to providers spontaneously; in contrast,16% did so only when asked directly [42].

Barriers to Discussion: Providers

Given findings that patients are not likely to bring up these concerns spontaneously, providers should ensure that concerns are addressed by engaging patients directly in conversations regarding sexual health. Unfortunately, data suggest this does not happen routinely. As with patients, multiple barriers exist to that can explain why providers may not engage in sexual health discussions [43]. Time constraint was shown to be a real issue in a survey of gynecologic oncologists in New England, where less than 50% of doctors practiced taking a sexual history with new patients and only 20% felt they had sufficient time to discuss sexual concerns [44]. Beyond time, studies also suggest clinicians often make assumptions about patients that “justify” not inquiring about sexual health. These assumptions can be varied, based on factors such as age (the older the patient, the likelihood [is that] they are not interested), overall prognosis (patients with a poor prognosis are likely not interested), and whether the patient has a current partner (single people are less likely to be interested because they are not sexually active) [45, 46].

Evaluating Sexual Health

Although it is not the intent of this paper to educate oncologists on becoming sexual health experts, we believe it is important that oncologists become more comfortable discussing and screening for sexual health. Clinicians should be aware of the importance of sexuality for most people, and a diagnosis of cancer does not change this. Consequently, taking a sexual history of our patients becomes as important as understanding their past medical and social history. In addition, by including a sexual history early on in the doctor-patient relationship, the clinician provides a signal to patients that he or she is open to discussing sexual issues, and that might enable patients to raise these issues in the future should they arise.

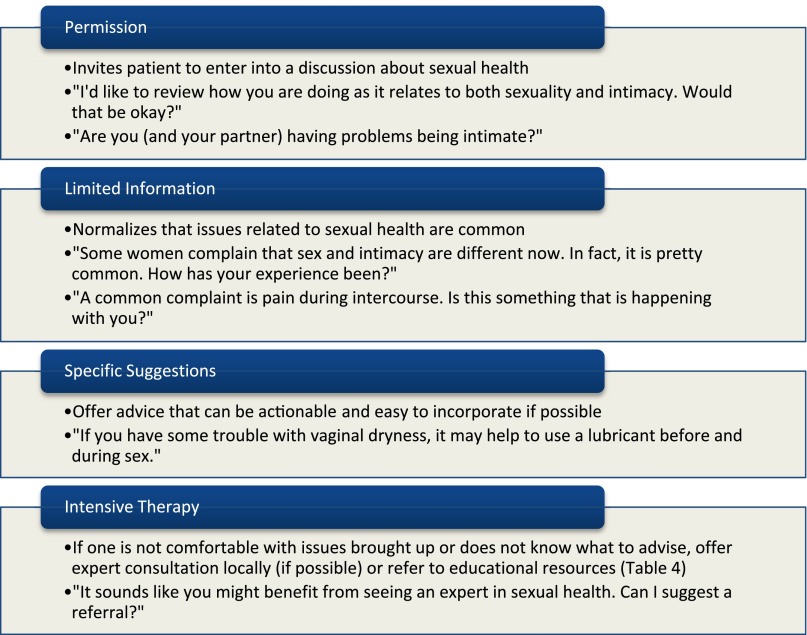

Clinicians should also incorporate questions about sexual health in their routine review of systems both during and after active treatment. Expert opinions indicate that adopting a patient-centric communication strategy can be effective [47, 48]. One approach to introducing discussions of sexual health is the PLISSIT model, which stands for “Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy” (Fig. 1) [49]. Park et al. have proposed the 5 As—Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange—which is a separate framework that builds on PLISSIT and is designed to aid clinicians in communicating with cancer survivors [50]. It is important that both open and closed questions be used, with sensitivity shown to the patient as she attempts to describe sexuality-related issues.

Figure 1.

Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy (PLISSIT) model for sexual conversations. Open-ended questions that can be used to begin discussions at each step are included, followed by closed-ended questions that may help during the conversation [49].

As discussed previously, clinicians should approach these discussions with very few assumptions; for example, the assumption that older women are not interested in sexual health is likely incorrect. This was shown in a study by Lindau and colleagues, who reported that a high proportion of patients (both male and female) from 60 to 90 years old remained sexually active (73% up to age 64, 53% up to age 74, and 26% up to age 85) [51].

Beyond a focus on the sexual history, discussion involves evaluation for potential contributing factors, outside of cancer and its treatment, that may be correctable. These include comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, hypothyroidism, diabetes), medications (e.g., β-blockers, antidepressants), and social conditions, such as issues related to the partner (e.g., comorbidities) and/or other stressors (e.g., work, finances).

Finally, clinicians should recognize that sexual activity is not synonymous with intimacy. This was highlighted in a recent study by Perz et al. that involved over 40 patients, their partners, (n = 35) and clinicians (n = 37) [52]. The authors showed that although clinicians tended to emphasize their queries on the ability of their patients to perform sexually, patients and their partners cautioned that the inability to perform should not be presumed to mean there was a lack of intimacy. Indeed, intimacy in and of itself was valued by patients, and alternative means of expressing intimacy could be highly satisfying, despite being unable or uninterested in having penile-vaginal intercourse (the “coital imperative”).

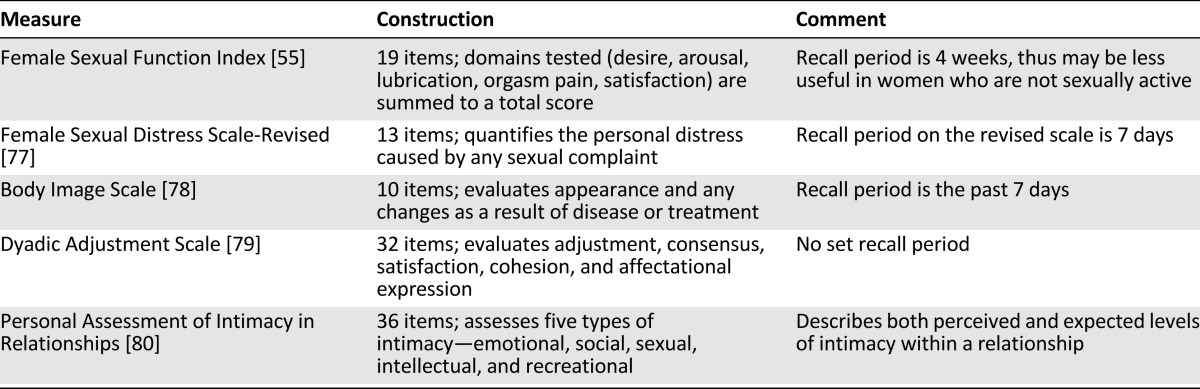

The evaluation of sexual health can also be aided by the use of validated questionnaires (Table 1). Instruments that specifically examine sexual function include the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and the Female Sexual Distress Scale [53, 54]. One of the most commonly administered is the FSFI, which is composed of 19 questions that characterize different domains of sexual function. It has been validated for heterosexual women with a history of cancer [55], and a modified version specific to women who have sex with women has been published [56]. Despite its frequent use, it is limited by its period of recall of activity (4 weeks), which has raised questions about its validity among women who are not currently sexually active [55, 57]. Despite these concerns, the author (D.S.D.) has used the FSFI prospectively in a specialized sexual health center at one academic cancer program, has found it to be acceptable to women referred, and found that it can be used to monitor women longitudinally [48]. Beyond those for sexual function, various questionnaires are available to help evaluate other aspects of sexual health, including body image, quality of relationships, and intimacy within relationships. These questionnaires are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of validated questionnaires for sexual health

For women who complain of specific issues such as pain with penetration or vaginal symptoms (e.g., dryness), the evaluation should include a pelvic examination. During the examination, the vulva and vagina are inspected for atrophy, vaginal length, and caliber of the vaginal vault. The exam may elicit pain with digital penetration, and this may be symptomatic of dyspareunia. If the oncology clinician does not feel comfortable performing the exam, prompt referral to another clinician (e.g., the patient’s gynecologist or a sexual health specialist) should be undertaken.

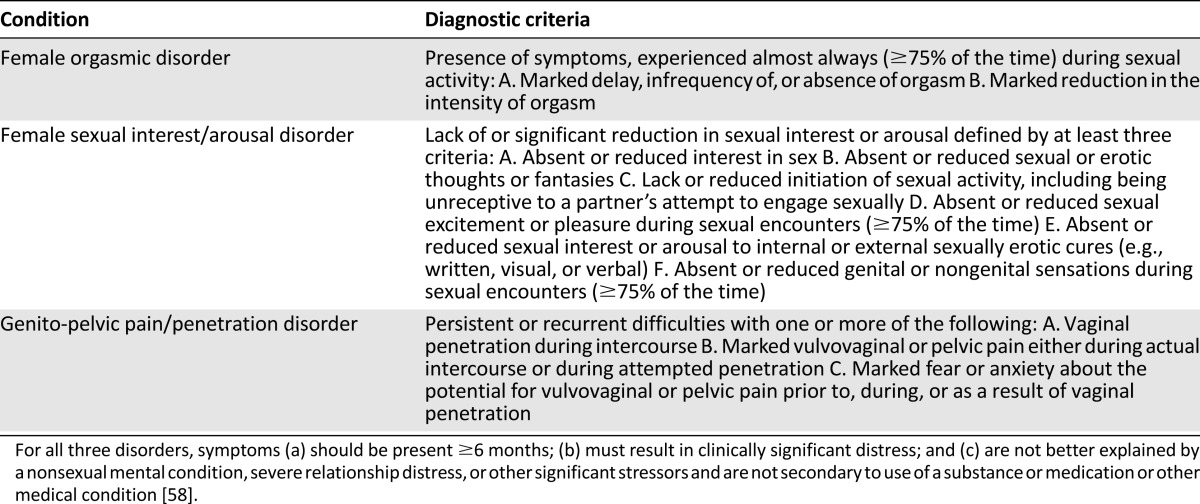

Female sexual dysfunction is classified using criteria in the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-V) [58]. The classification represents a departure from the prior manual (fourth edition, text revision). Instead of classifications based on whether the condition was related to either psychological factors alone or combined with biologic factors, the DSM-V represents a recognition that in most clinical situations, the condition can be traced to a combination of both types of factors.

Using DSM-V terminology, female orgasmic disorder remains its own diagnosis; however, the pain syndromes—vaginismus (defined as pain with penetration of the vagina resulting from smooth muscle spasms) and dyspareunia (generally characterized as pain with intercourse)—are now considered one condition, “genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder.” In addition, disorders of interest and arousal (hypoactive sexual desire disorder and female sexual arousal disorder, respectively, in the fourth edition, text revision) have been combined into “female sexual interest/arousal disorder.” For each disorder, two subtypes are used to classify them further: “lifelong versus acquired” and “generalized versus situational.” The new diagnostic criteria are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification of female sexual dysfunction

For any of these criteria, a minimum of duration of 6 months is required. In addition, the classification of sexual dysfunction requires that the presence of symptoms result in distress or the inability to respond sexually or experience sexual pleasure. Finally, it requires that symptoms not be secondary to another etiology (e.g., drug or substance side effect or as a consequence of another disease process).

Approach to Management

Although a comprehensive review on the management approach to women with sexual concerns is beyond the scope of this article, oncology clinicians should be aware that multiple treatment pathways are available for these patients [5, 59, 60]. In addition, should clinicians find themselves at the limits of either comfort or knowledge on the topic, referral to a sexual health specialist is always an option. What follows is a limited review of endocrine and nonendocrine therapeutic modalities that are likely to be encountered during discussions with patients.

Endocrine Therapies

Vaginal estrogen is an effective treatment for vaginal dryness [61] and can be prescribed as a cream, a ring, or a tablet [54]. Its use in women with hormone receptor-sensitive cancers requires an informed discussion of the potential benefits and risks of treatment in light of low-quality evidence that vaginal estrogen can result in detectable increases in serum estrogen [62]; however, the clinical significance of this finding is unclear. A recent study that included more than 13,000 women with breast cancer found no increase in the recurrence risk for women with breast cancer treated with endocrine therapy, whether or not local estrogen therapy was administered (rate ratio of recurrence between estrogen replacement therapy users to nonusers: 0.78; 95% confidence interval: 0.48–1.25) [63]. Still, and in the absence of prospective data, the use of estrogen in these women should be informed by the patient’s preferences with input from all of her involved providers (e.g., oncologist, sexual health specialist, and primary care provider).

Beyond local estrogen therapy, a new selective estrogen receptor modulator was approved for the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Ospemifene acts as an estrogen agonist specifically in the vagina and appears to exert no apparent estrogenic effect elsewhere, including within the endometrium and breast. In the randomized trial that resulted in its approval, treatment significantly improved atrophic symptoms and dyspareunia compared with placebo [64]; however, this agent has not been specifically evaluated in survivors of cancer, who were excluded in the randomized trial.

Beyond questions of efficacy, we do not routinely prescribe testosterone, given the lack of safety data, especially as it relates to cancer survival endpoints. For women with hormonally sensitive cancers, there is the additional concern that testosterone can be converted or aromatized to estrogen, which may reactivate, promote, or stimulate tumor growth.

Transdermal testosterone is an effective treatment for women with low libido [65, 66], hypoactive sexual desire [67], and impaired sexual function as a result of oophorectomy [68]; however, its role in the treatment of sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors is unclear. At least one randomized trial suggests it does not have an impact on libido for this population. In the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N02C3 trial, 150 female cancer survivors who were randomly assigned to a testosterone preparation (2% testosterone in Vanicream) or a placebo preparation for 4 weeks, followed by treatment with the opposite preparation for the subsequent 4 weeks [69]. During treatment with active testosterone, statistically significant increases in the serum testosterone levels were recorded; however, there was no change in desire levels in either arm. Beyond questions of efficacy, we do not routinely prescribe testosterone, given the lack of safety data, especially as it relates to cancer survival endpoints. For women with hormonally sensitive cancers, there is the additional concern that testosterone can be converted or aromatized to estrogen, which may reactivate, promote, or stimulate tumor growth. In addition, testosterone has a known risk profile that includes increased facial and body hair growth (hirsutism), weight gain, clitoromegaly, hair loss (alopecia), and elevations in lipid profiles or liver enzymes.

Other endocrine therapies under investigation include intravaginal preparations of dehydroepiandrosterone, which aims to enhance local sex steroid concentrations with minimal increases in systemic concentrations of estradiol or testosterone [70], and the 5-hydroxytryptamine 1A receptor inhibitor flibanserin [71]. Further evaluations of these agents are required to understand their efficacy and safety in these patients.

Nonendocrine Therapies

Nonendocrine treatments are available, predominantly for the relief of vaginal symptoms. These include vaginal moisturizes and suppositories for vaginal dryness. Beyond pharmacologic interventions, both dilators to treat genito-pelvic pain/penetration syndrome and the liberal use of lubrication can aide penetrative intercourse.

Vaginal moisturizers, such as polycarbophilic moisturizers (e.g., Replens) or vaginal pH-balanced gels (e.g., RepHresh), are prescribed often, although the data on their efficacy are limited. One small study of 45 patients with breast cancer who experienced vaginal dryness and dyspareunia found that Replens and a placebo preparation were equally effective in relieving symptoms [72]. In a separate randomized, placebo-controlled study that included 86 women, the vaginal pH-balanced gel was more effective in relieving both dryness and dyspareunia [73]. The frequency of use of these vaginal moisturizes is guided by the severity of symptoms, and use can be once every 3 days to daily. For sexually active women who experience issues with vaginal chafing or discomfort, use of moisturizers several hours before intercourse may also provide relief. Beyond vaginal moisturizers, vaginal suppositories that contain vitamin A or vitamin E can also be used, although data about the effectiveness of treatment are limited [74].

For patients who complain of pain with vaginal penetration, vaginal dilators are often recommended. These dilators are made of either medical-grade plastics or silicone and come in graduated sizes that range from 14 mm to 38 mm. If used, we recommend that women use them in the morning and incorporate them as part of a usual routine. Patients should be counseled to use them at least three times a week and should be seen every 3–4 weeks to assess progress.

Women who have vaginal symptoms should also be counseled on the liberal use of water- or silicone-based lubricants. The patient should be instructed to apply them liberally and generously, both on herself and her partner, before and during a particular sex event. Although no comparative studies have been performed in women with cancer, one trial that involved more than 2,400 women without cancer showed that, compared with no lubricant use, both types resulted in higher ratings of sexual pleasure and satisfaction during both solo sex and penile-to-vaginal intercourse. Notably, water-based lubricants rated higher than silicone-based lubricants for penile-to-anal intercourse, suggesting that they may be preferred for women for whom alternatives to vaginal intercourse are needed [75].

For women without a current partner, psychosocial support is important, not only to get through the cancer experience but also to help work through issues that may become relevant should a new relationship start. These include issues regarding when to disclose a cancer diagnosis and prognosis as part of her past, sexual function in general, and concerns about future fertility and parenthood. The issues faced by these women were the subject of a study conducted by Kurowecki and Fergus, in which 15 breast cancer survivors who were either actively dating or in a new relationship following their index cancer diagnosis were interviewed [76]. The major themes described by these women included (a) extreme vulnerability related to the diagnosis of breast cancer, (b) their obligation to disclose their cancer history, and (c) the importance of the new relationship in helping re-establish a new sense of self. Their findings indicate that even for women who are not in stable relationships, new and future partnerships can be an important aspect of recovery toward a new normal.

Oncology sexual health experts may be called on to assess and develop treatment plans for patients in whom sexual health issues are beyond the scope, comfort, or expertise of oncology clinicians by assembling an individualized treatment plan that may also include referral to mental health specialists, physical therapy, couples therapy, and/or sex therapists.

Conclusion

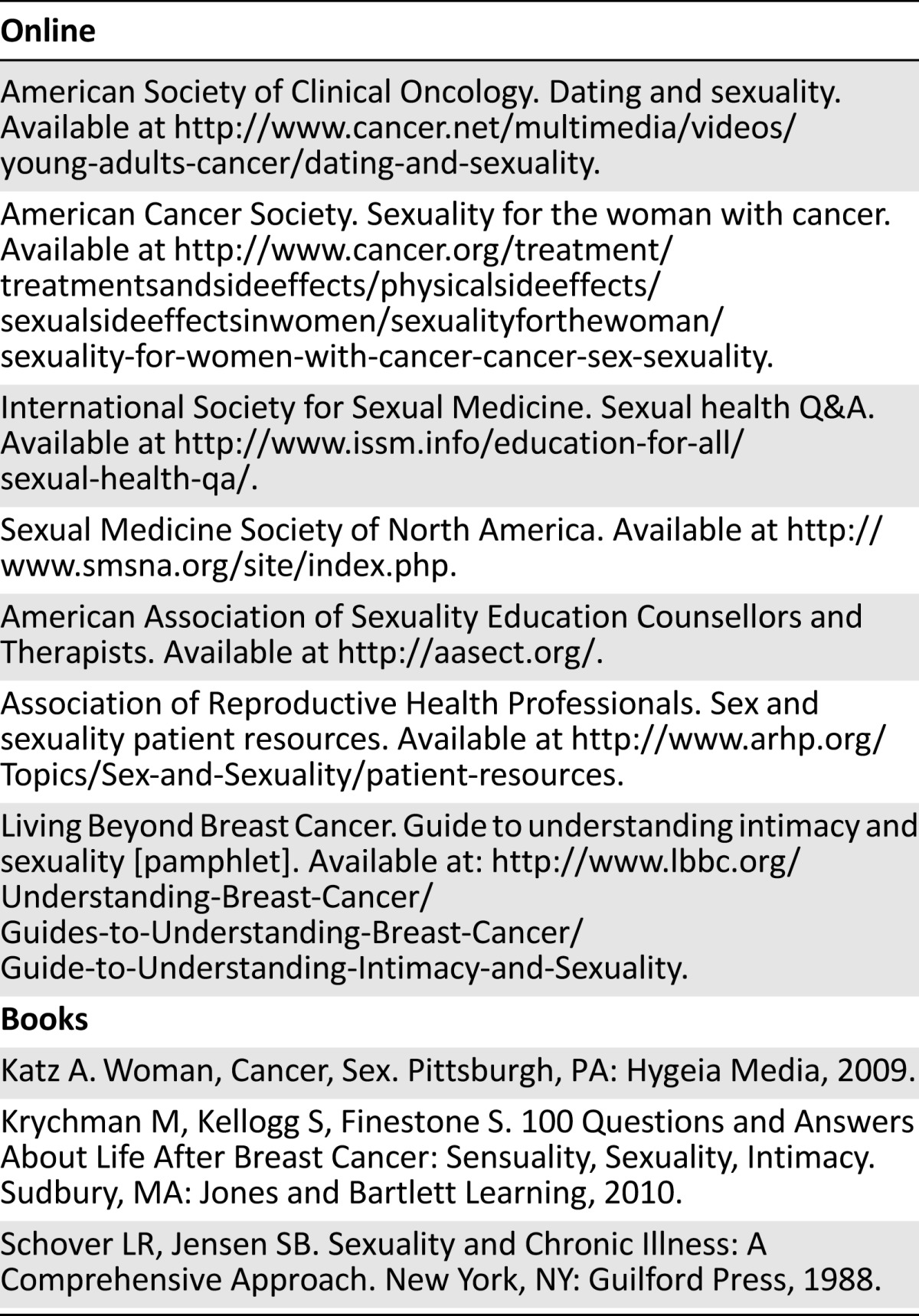

Sexual quality of life is an important aspect for women after cancer. Providers should proactively discuss sexual health with their patients or consider consultation with a sexual health provider. For women with these issues, both sexuality and intimacy should be jointly considered. Clinicians should be encouraged to address these issues early on in the treatment pathway and to encourage patients to discuss them. Although there is no one therapeutic strategy for sexual concerns for female cancer survivors, clinicians should be aware of the multiple modalities present, particularly as they pertain to pharmaceuticals, vaginal moisturizers, and vaginal lubricants. In the approach to treatment, recognizing the availability of local experts, educational resources (Table 3), and sexual health experts is also important in the provision of multidisciplinary care.

Table 3.

Suggested resources

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Don S. Dizon, Daphne Suzin

Collection and/or assembly of data: Don S. Dizon

Data analysis and interpretation: Don S. Dizon

Manuscript writing: Don S. Dizon, Daphne Suzin, Susanne McIlvenna

Final approval of manuscript: Don S. Dizon, Daphne Suzin, Susanne McIlvenna

Disclosures

Don S. Dizon: UpToDate (E). The other authors indicate no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship Mission: While we hope for the cure, we must focus on the care. Available at: http://www.canceradvocacy.org/about-us/our-mission/ Accessed 10/13/2013.

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2013. Available at http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2013 Accessed 10/23/13.

- 3.de Moor JS, Mariotto AB, Parry C, et al. Cancer survivors in the United States: Prevalence across the survivorship trajectory and implications for care. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:561–570. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GLOBOCAN 2008 Update: Cancer prevalence estimates are now available. Available at: http://www.iarc.fr/en/media-centre/iarcnews/2011/globocan2008-prev.php Accessed 10/23/13.

- 5.Desimone M, Spriggs E, Gass JS, et al. Sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors. Am J Clin Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318248d89d. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masters W, Johnson V. Human Sexual Response. New York, NY: Little Brown & Co.; 1966. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaplan HS, Horwith M. The Evaluation of Sexual Disorders: Psychological and Medical Aspects. Abingdon, U.K.: Brunner/Mazel; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Basson R. Female sexual response: The role of drugs in the management of sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:350–353. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sand M, Fisher WA. Women’s endorsement of models of female sexual response: The nurses’ sexuality study. J Sex Med. 2007;4:708–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kornblith AB, Herndon JE, II, Zuckerman E, et al. Social support as a buffer to the psychological impact of stressful life events in women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2001;91:443–454. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010115)91:2<443::aid-cncr1020>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brotto LA, Yule M, Breckon E. Psychological interventions for the sexual sequelae of cancer: A review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:346–360. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0132-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li Q, Loke AY. A literature review on the mutual impact of the spousal caregiver-cancer patients dyads: ‘Communication’, ‘reciprocal influence’, and ‘caregiver-patient congruence.’. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2013.09.003. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manne S, Badr H. Intimacy and relationship processes in couples’ psychosocial adaptation to cancer. Cancer. 2008;112(suppl):2541–2555. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perelman MA. The sexual tipping point: A mind/body model for sexual medicine. J Sex Med. 2009;6:629–632. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andersen BL. Sexual functioning morbidity among cancer survivors. Current status and future research directions. Cancer. 1985;55:1835–1842. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850415)55:8<1835::aid-cncr2820550832>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu T, Ennis M, Hood N, et al. Quality of life in long-term breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3540–3548. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Borgne G, Mercier M, Woronoff AS, et al. Quality of life in long-term cervical cancer survivors: A population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: A follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:39–49. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kornblith AB, Ligibel J. Psychosocial and sexual functioning of survivors of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30:799–813. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganz PA. Sexual functioning after breast cancer: A conceptual framework for future studies. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:105–107. doi: 10.1023/a:1008218818541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckjord E, Campas BE. Sexual quality of life in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25:19–36. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burwell SR, Case LD, Kaelin C, et al. Sexual problems in younger women after breast cancer surgery. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2815–2821. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilmoth MC. The aftermath of breast cancer: An altered sexual self. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24:278–286. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200108000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bergmark K, Avall-Lundqvist E, Dickman PW, et al. Vaginal changes and sexuality in women with a history of cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1383–1389. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Becker M, Malafy T, Bossart M, et al. Quality of life and sexual functioning in endometrial cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilmoth MC, Hatmaker-Flanigan E, LaLoggia V, et al. Ovarian cancer survivors: Qualitative analysis of the symptom of sexuality. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011;38:699–708. doi: 10.1188/11.ONF.699-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reese JB, et al. Gastrointestinal ostomies and sexual outcomes: A comparison of colorectal cancer patients by ostomy status. Support Care Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1998-x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Panjari M, Bell RJ, Burney S, et al. Sexual function, incontinence, and wellbeing in women after rectal cancer—a review of the evidence. J Sex Med. 2012;9:2749–2758. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Böhm G, Kirschner-Hermanns R, Decius A, et al. Anorectal, bladder, and sexual function in females following colorectal surgery for carcinoma. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:893–900. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0498-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hendren SK, O’Connor BI, Liu M, et al. Prevalence of male and female sexual dysfunction is high following surgery for rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2005;242:212–223. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000171299.43954.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M, Clark MA. Lesbian and bisexual women's adjustment after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2013;19:280–92. doi: 10.1177/1078390313504587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, et al. Early-stage cervical carcinoma, radical hysterectomy, and sexual function. A longitudinal study. Cancer. 2004;100:97–106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Figueiredo MI, Cullen J, Hwang Y-T, et al. Breast cancer treatment in older women: Does getting what you want improve your long-term body image and mental health? J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4002–4009. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fobair P, Stewart SL, Chang S, et al. Body image and sexual problems in young women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15:579–594. doi: 10.1002/pon.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roe H. Chemotherapy-induced alopecia: Advice and support for hair loss. Br J Nurs. 2011;20:S4–S11. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.Sup5.S4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krychman ML, Carter J, Aghajanian CA, et al. Chemotherapy-induced dyspareunia: A case study of vaginal mucositis and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin injection in advanced stage ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:561–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumgart J, Nilsson K, Evers AS, et al. Sexual dysfunction in women on adjuvant endocrine therapy after breast cancer. Menopause. 2013;20:162–168. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31826560da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pieterse QD, Maas CP, ter Kuile MM, et al. An observational longitudinal study to evaluate miction, defecation, and sexual function after radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:1119–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kelemen G, Varga Z, Lázár G, et al. Cosmetic outcome 1-5 years after breast conservative surgery, irradiation and systemic therapy. Pathol Oncol Res. 2012;18:421–427. doi: 10.1007/s12253-011-9462-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marwick C. Survey says patients expect little physician help on sex. JAMA. 1999;281:2173–2174. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.23.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Pfizer Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Available at http://www.pfizerglobalstudy.com/study/study-results.asp Accessed 5/7/2011.

- 42.Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR, Grill J. Brief sexual inquiry in gynecologic practice. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:425–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ussher JM, Perz J, Gilbert E, et al. Talking about sex after cancer: A discourse analytic study of health care professional accounts of sexual communication with patients. Psychol Health. 2013;28:1370–1390. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.811242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiggins DL, Wood R, Granai CO, et al. Sex, intimacy, and the gynecologic oncologists: Survey results of the New England Association of Gynecologic Oncologists (NEAGO) J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25:61–70. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hordern A. Intimacy and sexuality for the woman with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23:230–236. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200006000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hordern AJ, Street AF. Let’s talk about sex: Risky business for cancer and palliative care clinicians. Contemp Nurse. 2007;27:49–60. doi: 10.5555/conu.2007.27.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parish SJ, Rubio-Aurioles E. Education in sexual medicine: Proceedings from the International Consultation in Sexual Medicine, 2009. J Sex Med. 2010;7:3305–3314. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hill EK, et al. A prospective evaluation of quality of life, sexual function, and depression in women referred to a sexuality clinic for female cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;125:278a. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Annon JS. Behavioral Treatment of Sexual Problems: Brief Therapy. New York, NY: Harper & Row, 1976;45.

- 50.Park ER, Norris RL, Bober SL. Sexual health communication during cancer care: Barriers and recommendations. Cancer J. 2009;15:74–77. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819587dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762–774. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perz J, Ussher JM, Gilbert E. Constructions of sex and intimacy after cancer: Q methodology study of people with cancer, their partners, and health professionals. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:270. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Althof SE, Parish SJ. Clinical interviewing techniques and sexuality questionnaires for male and female cancer patients. J Sex Med. 2013;10(Suppl 1):35–42. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frechette D, Paquet L, Verma S, et al. The impact of endocrine therapy on sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women with early stage breast cancer: Encouraging results from a prospective study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;141:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2659-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J. Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118:4606–4618. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tracy JK, Junginger J. Correlates of lesbian sexual functioning. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2007;16:499–509. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyer-Bahlburg HFL, Dolezal C. The Female Sexual Function Index: A methodological critique and suggestions for improvement. J Sex Marital Ther. 2007;33:217–224. doi: 10.1080/00926230701267852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krychman ML, Katz A. Breast cancer and sexuality: Multi-modal treatment options. J Sex Med. 2012;9:5–13; quiz 14–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krychman ML. Sexual rehabilitation medicine in a female oncology setting. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:380–384. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Simunić V, Banović I, Ciglar S, et al. Local estrogen treatment in patients with urogenital symptoms. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2003;82:187–197. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00200-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kendall A, Dowsett M, Folkerd E, et al. Caution: Vaginal estradiol appears to be contraindicated in postmenopausal women on adjuvant aromatase inhibitors. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:584–587. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Le Ray I, Dell’Aniello S, Bonnetain F, et al. Local estrogen therapy and risk of breast cancer recurrence among hormone-treated patients: A nested case-control study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135:603–609. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2198-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Portman DJ, Bachmann GA, Simon JA, Ospemifene Study Group Ospemifene, a novel selective estrogen receptor modulator for treating dyspareunia associated with postmenopausal vulvar and vaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20:623–630. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318279ba64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davis SR, Moreau M, Kroll R, et al. Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2005–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nathorst-Böös J, Flöter A, Jarkander-Rolff M, et al. Treatment with percutanous testosterone gel in postmenopausal women with decreased libido—effects on sexuality and psychological general well-being. Maturitas. 2006;53:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kingsberg S, Shifren J, Wekselman K, et al. Evaluation of the clinical relevance of benefits associated with transdermal testosterone treatment in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2007;4:1001–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:682–688. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200009073431002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barton DL, Wender DB, Sloan JA, et al. Randomized controlled trial to evaluate transdermal testosterone in female cancer survivors with decreased libido; North Central Cancer Treatment Group protocol N02C3. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:672–679. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Labrie F, Martel C, Bérubé R, et al. Intravaginal prasterone (DHEA) provides local action without clinically significant changes in serum concentrations of estrogens or androgens. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;138:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Katz M, DeRogatis LR, Ackerman R, et al. Efficacy of flibanserin in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Results from the BEGONIA trial. J Sex Med. 2013;10:1807–1815. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Loprinzi CL, Abu-Ghazaleh S, Sloan JA, et al. Phase III randomized double-blind study to evaluate the efficacy of a polycarbophil-based vaginal moisturizer in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:969–973. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee Y-K, Chung HH, Kim JW, et al. Vaginal pH-balanced gel for the control of atrophic vaginitis among breast cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:922–927. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182118790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Costantino D, Guaraldi C. Effectiveness and safety of vaginal suppositories for the treatment of the vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: An open, non-controlled clinical trial. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2008;12:411–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Herbenick D, Reece M, Hensel D, et al. Association of lubricant use with women’s sexual pleasure, sexual satisfaction, and genital symptoms: A prospective daily diary study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:202–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kurowecki D, Fergus KD. Wearing my heart on my chest: Dating, new relationships, and the reconfiguration of self-esteem after breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/pon.3370. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Derogatis L, Clayton A, Lewis-D’Agostino D, et al. Validation of the female sexual distress scale-revised for assessing distress in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med. 2008;5:357–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, et al. A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:189–197. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00353-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Spanier GB. The measurement of marital quality. J Sex Marital Ther. 1979;5:288–300. doi: 10.1080/00926237908403734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schaefer MT, Olson DH. Assessing intimacy: The Pair Inventory. J Marital Fam Ther. 1981;7:47–60. [Google Scholar]