Abstract

Purpose

To design and synthesize prodrugs of gatifloxacin targeting OCT, MCT, and ATB (0, +) transporters and to identify a prodrug with enhanced delivery to the back of the eye.

Method

Dimethylamino-propyl, carboxy-propyl, and amino-propyl(2-methyl) derivatives of gatifloxacin (GFX), DMAP-GFX, CP-GFX, and APM-GFX, were designed and synthesized to target OCT, MCT, and ATB (0, +) transporters, respectively. LC-MS method was developed to analyze drug and prodrug levels in various studies. Solubility and Log D (pH 7.4) were measured for prodrugs and the parent drug. Permeability of the prodrugs was determined in cornea, conjunctiva, and sclera-choroidretinal pigment epitheluim (SCRPE) and compared with gatifloxacin using Ussing chamber assembly. Permeability mechanisms were elucidated by determining the transport in the presence of transporter specific inhibitors. 1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium iodide (MPP+), nicotinic acid sodium salt, and α-methyl-DL-tryptophan were used to inhibit OCT, MCT, and ATB (0, +) transporters, respectively. A prodrug selected based on in vitro studies was administered as an eye drop to pigmented rabbits and the delivery to various eye tissues including vitreous humor was compared with gatifloxacin dosing.

Results

DMAP-GFX exhibited 12.8-fold greater solubility than GFX. All prodrugs were more lipophilic, with the measured Log D (pH 7.4) values ranging from 0.05 to 1.04, when compared to GFX (Log D: -1.15). DMAP-GFX showed 1.4-, 1.8-, and 1.9-fold improvement in permeability across cornea, conjunctiva, as well as SCRPE when compared to GFX. Moreover, it exhibited reduced permeability in the presence of MPP+ (competitive inhibitor of OCT), indicating OCT-mediated transport. CP-GFX showed 1.2-, 2.3- and 2.5-fold improvement in permeability across cornea, conjunctiva and SCRPE, respectively. In the presence of nicotinic acid (competitive inhibitor of MCT), permeability of CP-GFX was reduced across conjunctiva. However, cornea and SCRPE permeability of CP-GFX was not affected by nicotinic acid. APM-GFX did not show any improvement in permeability when compared to GFX across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE. Based on solubility and permeability, DMAP-GFX was selected for in vivo studies. DMAP-GFX showed 3.6- and 1.95-fold higher levels in vitreous humor and CRPE compared to that of GFX at 1 hour after topical dosing. In vivo conversion of DMAP-GFX prodrug to GFX was quantified in tissues isolated at 1 hour after dosing. Prodrug-to-parent drug ratio was 8, 70, 24, 21, 29, 13, 55, and 60 % in cornea, conjunctiva, iris-ciliary body, aqueous humor, sclera, CRPE, retina, and vitreous humor, respectively.

Conclusions

DMAP-GFX prodrug enhanced solubility, Log D, as well as OCT mediated delivery of gatifloxacin to the back of the eye.

Keywords: Organic cation transporter, monocarboxylic acid transporter, amino acid transporter, prodrugs, ocular delivery, endophthalmitis, gatifloxacin, drug delivery

Introduction

Endophthalmitis is an inflammatory condition of the intraocular compartments (aqueous or vitreous humor) usually caused by infection. Endophthalmitis results from direct inoculation as a complication of ocular surgical procedures including cataract surgery, glaucoma filtration surgery, retinal re-attachment, and radial keratotomy 1. Post-cataract endopthalmitis is the most common form endophthalmitis. Approximately 5 % of individuals aged over 70 years in USA undergo cataract every year 2. Although rare, post cataract endophthalmitis is often associated with significant morbidity 3. In severe cases of endophthalmitis, vitrectomy is used to remove dead bacteria and damaged tissues. Analysis of complete cataract cases from Medicare database during 2003 to 2004, determined that 0.14 to 0.17 % cases are associated with endophthalmitis 4. Although this is a small percentage, the increased use of intravitreal injections for the treatment of ocular diseases along with growing number of ocular surgeries may lead to greater incidence of ocular infections 5. Decreased vision and permanent loss of vision are common complications of endophthalmitis 3, 6. Patients may require enucleation to eradicate a blind and painful eye that is unresponsive to antibiotics 7. Currently endophthalmitis management is achieved by administration of antibiotics either by intravitreal or systemic administration 8. However, intravitreal and systemic routes suffer from disadvantages. Antibiotics administered systemically suffer from possible systemic side effects 9. Although intravitreal administration solves this problem, photoreceptors and other cells of retina are very sensitive and might be damaged by exposure of high levels of antibacterial agents following direct intravitreal injections 10. In addition, intravitreal injections are invasive and repeated injections can result in retinal detachment as well as endophthalmitis.

Fluoroquinolone antibiotics with a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity are commonly used to treat ocular surface infections 11. Currently, fourth generation ophthalmic fluorquinolones such as gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin are commonly used off label before and after ocular surgery to minimize the risk of postoperative endophthalmitis 12, 13. Gatifloxacin provides a suitable choice for preventing postoperative endophthalmitis based on its attributes such as rapid killing and relatively benign effect on wound healing compared to moxifloxacin 14. Moreover, gatifloxacin showed comparatively less inhibition of proliferation and migration of corneal epithelial cells than moxifloxacin 14. Hariprasad et al. have shown that gatifloxacin achieves rapid and effective vitreous levels after oral administration 15. However, unfortunately oral gatifloxacin was withdrawn from the market owing to its adverse side effects such as hypo- and hyper- glycemia 16. Recently, Costella et al. quantified the vitreous levels of fourth generation fluoroquinolones including gatifloxacin (0.3% - Zymar) and moxifloxacin (0.5% Vigamox) after topical administration, and found that vitreous levels of both drugs were well below the MIC90 of most bacteria implicated in endophthalmitis 17. Since endophthalmitis is associated with posterior tissues of the eye, it is imperative that therapeutic levels of antibiotics should be available in posterior tissues such as vitreous humor. Unfortunately, it is challenging to render drug delivery to the posterior segment due to the unique anatomic and physiological barriers present in the cornea, conjunctiva, and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Various transporters are reported to be present at the cornea, conjunctiva and RPE barriers. Prior investigations identified the presence of solute transporters in ocular tissues from rat, mouse, rabbit and humans. Zhang et al. showed mRNA expression in human ocular tissues for transporters including organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) and organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) 18. Rajan et al. showed mRNA expression of organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3) in mouse RPE and neural retina 19. Localization of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and monocarboxylate transporter 3 (MCT3) transporters was shown in both rat 20 and human ocular tissues 21. Ganapathy and co-workers showed the expression of amino acid transporter ATB (0, +) in mouse (conjunctiva, RPE, and retina) 22 and human (cornea) 23 eye tissues. One can potentially utilize these transporters for improving delivery of drugs to the anterior as well as posterior tissues. Thus, the objective of this study was to develop prodrugs of gatifloxacin based on the transporters present in the cornea, conjunctiva and RPE, in order to improve GFX delivery to eye tissues, especially those in the back of the eye. We synthesized prodrugs intended to target OCT, MCT, and ATB (0, +) transporters and assessed their solubility, Log D, and in vitro permeability across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE. Based on the in vitro properties, we selected a prodrug and assessed its ability to improve delivery of gatifloxacin to the vitreous humor in pigmented rabbits.

Experimental Section

Materials

Gatifloxacin sesquihydrate (racemic mixture) was purchased from AK Scientific, Inc (Union City, CA). All the other chemical and solvents including Boc-anhydride, thionyl chloride, anhydrous dimethyl formamide (DMF), N, N-diisopropylamine (DIEA), tetrahydrofuran (THF), O-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate (HBTU), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium iodide (MPP+), nicotinic acid sodium salt, α-methyl-DL-tryptophan were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St.Louis, MO). Rabbit eyes were purchased from Pel-Freez Arkansas (Lowell, AR) and bovine eyes were purchased from G & C packing company (Colorado Springs, CO).

Chemistry

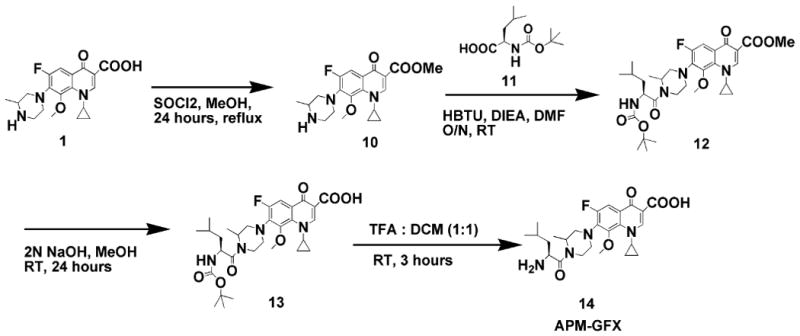

Prodrugs synthesis (Schemes 1 and 2)

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of dimethylamino-propyl-gatifloxacin (DMAP-GFX) and carboxy-propyl-gatifloxacin (CP-GFX) prodrugs targeting OCT and MCT transporters, respectively.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of aminopropyl(2-methyl)-gatifloxacin (APM-GFX) prodrug intended for targeting ATB (0, +) transporter.

DMAP-GFX (5), a prodrug for OCT transporter

(±)-7-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (2)

Two hundred milligrams (0.53 mmol) of gatifloxacin sesquihydrate (1) was dissolved in dry tetrahydrofuran solvent (5.0 ml) and 0.5 ml of 1N NaOH was added to the reaction mixture. Subsequently, 124 mg (0.58 mmol) of Boc-anhydride was added and the mixture was stirred overnight under argon at room temperature (RT). After the completion of the reaction, the solvent was evaporated and the residue was neutralized with saturated ammonium chloride. Then the product was extracted into ethyl acetate (2 X 20 ml). Ethyl acetate layer was dried on sodium sulfate and evaporated. Finally, the residue was dried in vacuum and gives product 2 in 68% yield.

(±)-tert-butyl 4-(1-cyclopropyl-3-((3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbamoyl)-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinolin-7-yl)-2-methylpiperazine-1-carboxylate (4)

Eighty milligrams (0.17 mmol) of Boc-protected gatifloxacin (2) and 76 mg (0.2 mmol) of HBTU were dissolved in 3.0 ml dry DMF under argon and the reaction was stirred for 1 hour at RT. Then, 27 μl (0.21 mmol) of N1,N1-dimethylpropane-1,3-diamine (3) was added under argon atmosphere and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for overnight. The solvent was evaporated under rotary evaporator connected to a high vacuum; subsequently the residue was loaded onto silica column and the product was separated using dichloromethane:methanol (90:10) to give product 4 in 45 % yield.

(±)-1-cyclopropyl-N-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-7-(3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamide (5)

Forty milligrams (0.071 mmol) of the derivative 4 was dissolved in 3.0 ml of 1:2 (TFA:DCM) and stirred for 4 hours at RT. Completion of the reaction was monitored by TLC and ninhydrin stain. Once the reaction was complete, solvent was evaporated and the residue was dried for few hours under high vacuum to give product 5 in 75% yield.

CP-GFX (9), a prodrug for MCT transporter

(±)-4-((S)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-3-ethoxy-3-oxopropyl)phenyl 7-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1-cyclopropyl-6 -fluoro-8-methoxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (7)

Two hundred milligrams (0.42 mmol) of Boc-protected gatifloxacin (2), 240 mg (0.63 mmol) of HBTU, and 0.069 ml (0.40 mmol) of DIEA were dissolved in 4.0 ml of dry DMF under argon and the reaction was stirred for 1 hour at RT. Then, 80 mg (0.46 mmol) of (R)-ethyl 2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)acetate(6) was added under argon and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for overnight. The solvent was evaporated under rotary evaporator connected to a high vacuum; subsequently the residue was loaded on to silica column and the product was separated by dichloromethane:methanol (97.5:2.5) to give product 7 in 56 % yield.

(±)-4-(7-(4-(tert-butoxycarbonyl)-3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamido)butanoic acid (8)

Ninety milligrams (0.15 mmol) of ester derivative (7) was dissolved in 5.0 ml of HPLC grade methanol and 0.7 ml of 2N NaOH was added to the reaction mixture. Reaction was mixture was allowed to stir overnight at room temperature. About 60% of the starting material hydrolyzed; therefore, in order to drive the reaction to completion the reaction was warmed to 50 °C and stirred for 4 hours. Once the reaction was complete, methanol was evaporated and the reaction mixture was added with 1N HCl to neutralize the excess base. Subsequently, the product was extracted into ethyl acetate (20 ml). Ethyl acetate was dried over sodium sulfate and evaporated using a rotary evaporator to give product 8 in quantitative yield.

(±)-4-(1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-7-(3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxamido)butanoic acid (9)

Derivative 8 (50 mg, 0.089 mmol) was dissolved in 3.0 ml of 1:1 (TFA: DCM) and stirred for 3 hours at RT. Completion of the reaction was monitored by TLC and ninhydrin stain. Once the reaction is complete, solvent was evaporated and the residue was dried for few hours under high vacuum to give product 9 in 85 % yield.

APM-GFX (14), a prodrug for ATB (0, +) transporter

(±)-Methyl-1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-7-(3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate (10)

Two hundred and fifty milligrams (0.65 mmol) of gatifloxacin (1) was dissolved in 5.0 ml of HPLC grade methanol and the reaction flask was cooled to 0 °C. Subsequently, 0.052 ml (0.72 mmol) of thionyl chloride was added dropwise to the reaction mixture and the reaction contents were slowly brought to room temperature. Then the reaction was refluxed for 24 hours. Once the reaction was complete, solvent was evaporated and the contents were dried under high vacuum to remove the excess of thionyl chloride to give product 10 in quantitative yield.

Methyl-7-((R,S)-(4-((S)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-4-methylpentanoyl)-3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylate) (12)

One hundred and fifty milligrams (0.39 mmol) of ester derivative (12), 267 mg (0.71 mmol) of HBTU, and 0.135 ml (0.78 mmol) of DIEA were dissolved in 4.0 ml of dry DMF under argon and the reaction was stirred for 1 hour at RT. Then, 109 mg (0.47 mmol) of Boc-L-Leu-OH (11) was added under argon and the reaction mixture was stirred at RT for overnight. Once the reaction is complete, reaction contents were added with 5.0 ml of ice cold water to precipitate the product out. Product was extracted into ethyl acetate and the ethyl acetate layer was dried and evaporated to obtain the residue. This residue was then loaded onto a silica column and separated using dichloromethane:methanol (95:5) to give product 12 in 77% yield.

7-((R,S)-(4-((S)-2-((tert-butoxycarbonyl)amino)-4-methylpentanoyl)-3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid) (13)

One hundred and fifty milligrams (0.25 mmol) of the 12 was dissolved in 5.0 ml of HPLC grade methanol and 0.7 ml of 2N NaOH was added to the reaction mixture. Reaction mixture was stirred at 50 °C for 5 hours. Once the reaction was complete, methanol was evaporated and the reaction mixture was added with 0.5 ml of 1N HCl to neutralize the excess base. Subsequently, the product was extracted was extracted into ethyl acetate (20 ml). Ethyl acetate was dried over sodium sulfate and evaporated using a rotary evaporator to obtain the product. Residue obtained in this way is loaded onto a silica column and separated using dichloromethane:methanol (95:5) to give the product 13 in 80% yield.

7-((R,S)-(4-((S)-2-amino-4-methylpentanoyl)-3-methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-8-methoxy-4-oxo-1,4-dihydroquinoline-3-carboxylic acid (14)

Sixty milligrams (0.1 mmol) of derivative 13 was dissolved in 3.0 ml of 1:1 (TFA: DCM) and stirred for 3 hours at RT. Completion of the reaction was monitored by TLC and ninhydrin stain. Once the reaction was complete, solvent was evaporated and the residue was dried for few hours under high vacuum to give the product 14 in 90% yield.

Prodrug characterization

1H-NMR spectra were obtained using a Varian DRX400 at 400 MHz using deuterated chloroform, methanol and dimethyl sulfoxide solvents. Mass measurements were obtained using API-3000 triple quadruple mass spectrometry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) under positive ion mode. Further, purity of the prodrugs was estimated using a Waters HPLC with a PDA detector. Agilent C18 column (4.8 × 150 mm) was used along with 25 mM monobasic sodium phosphate buffer at pH3.5 (mobile phase A) and acetonitrile (mobile phase B). Gradient method was used, and the organic phase was increased from 20 to 50% over a duration of 30 minutes, and the organic phase was brought to 20 % B over 3 minutes and subsequently the column was re-equilibrated in 80% A and 20% B for 10 minutes before the next injection. High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) of all prodrugs were recorded using Q-TOF 2 (Waters, Milford, MA) under positive ionization mode.

Solubility studies

Thermodynamic solubility of prodrugs was determined in triplicate in water for injection at 37 °C. Excess amount of prodrug was weighed into eppendorf tubes and 0.5 ml of water for injection was added to each tube. Eppendorf tubes were incubated at 37 °C for 6 hours with shaking at 200 rpm. After incubation, samples were centrifuged at 13,500 rpm for 10 minutes. Two hundred and fifty microliters of supernatant was pipetted out and filtered through 0.45 micron disposable syringe filters. Filtrate was diluted further with water for injection and the absorbance of the filtrate was measured by UV spectroscopy. GFX prodrugs were monitored at 285 nm.

Estimation of pKa

Twenty millimolar gatifloxacin was prepared by dissolving 37.5 mg in 5.0 ml of 20 mM of HCl. Probe of the pH meter (Mettler Toledo, OH) was placed in the gatifloxacin solution, and 20 mM of NaOH was added in the increments of 0.1 ml. After every addition of sodium hydroxide, pH was allowed to stabilize and recorded. Volume of sodium hydroxide added versus the pH was plotted in Origin software (v7.5), and the pKa was calculated by fitting the curve using the Boltzman equation.

Estimation of Log D

Log D of the prodrugs was estimated at pH 7.4 using PBS buffer (pH 7.4) and 1-octanol according shake-flask method. PBS buffer and 1-octanol were saturated with each other overnight before using it for the Log D studies. Log D was measured at 100.0 μg/ml concentration. Prodrug stocks were made in PBS buffer saturated with 1-octanol. Two hundred and fifty microliters of prodrug stocks were added with 250 μl of 1-octanol saturated with PBS buffer. Then samples were incubated at 37 °C for 6 hours in a shaker set to 200 rpm. At the end of incubation, samples were centrifuged at 13,000 g (AccuSpin Micro 17, Fisher Scientific) for 10 minutes. Aqueous layer was isolated and absorbance was measured at 285 nm.

In vitro transport and elucidation of mechanism studies

All permeability studies across cornea and SCRPE were conducted using isolated tissues of New Zewland White (NZW) rabbits obtained from Pel-Freez Arkansas (Lowell, AR). Conjunctiva was not present in the rabbit eyes supplied by Pel-Freez Arkansas. Therefore, transport studies across conjunctiva were conducted using conjunctiva obtained from bovine eyes procured from G & C Packing Co (Colorado Springs, CO). Isotonic assay buffer pH 7.4 was used for conducting the study. Assay buffer had the following composition: NaCl (122 mM), NaHCO3 (25 mM), MgSO4 (1.2 mM), K2HPO4 (0.4 mM), CaCl2 (1.4 mM), HEPES (10 mM), and glucose (10 mM). GFX and GFX prodrugs were studied at 200 μM donor concentration in presence and absence of inhibitors. MPP+ (500 μM), nicotinic acid, and α-methyl-DL-Tryptophan were used as inhibitors of OCT, MCT, and ATB (0, +) transporters respectively. Isolated tissues were mounted on modified Ussing chambers (Navicyte, Sparks, NY) such that the epithelium side of cornea or conjunctiva or episcleral side of SCRPE was facing the donor chamber and endothelium of cornea or retina side of the SCRPE was facing the receiver chamber. Chambers were filled with 1.5 ml of isotonic assay buffer with (donor side) or without (receiver side) drug. During the transport study, bathing fluids were maintained at 37 °C using circulating warm water, and pH was maintained at 7.4 using 95% air − 5% CO2 aeration 24. At predetermined time intervals (0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 2.5, and 3.0 for rabbit tissues; 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 hours for bovine tissues), a 0.2 ml of sample was collected from the receiver side and the lost volume was compensated with fresh assay buffer preequilibriated at 37 °C. The drug and prodrug levels were analyzed using LC-MS/MS assay. Permeability data was corrected for dilution of the receiver solution with sample volume replenishment.

In vivo tissue distribution study in rabbits

Animal studies were conducted in accordance with the ARVO Statement for use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and guidelines by the Animal care Committee of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical campus. Male New Zealand Satin (NZS) pigmented rabbits in the weight range of 1.8 to 3 kg were obtained from Western Oregon Rabbit Company (Philmoth, OR). Rabbits were divided into two groups (2 animals each; 4 eyes). One group received GFX solution (5 mg/ml) in sterile phosphate buffer saline (PBS) and another group received DMAP-GFX prodrug (35 mg/ml) solution in PBS. Rabbits were allowed to stabilize in restrainer for 5-10 minutes. Topical eye drop (30 μl) of drug solution was applied in both eyes of rabbit using a positive displacement pipette (Gilson 10-100μl) and sterile tips. To minimize the runoff of instilled dose, the eyelids were gently closed for few seconds after dosing. The time of dose administered was recorded for each animal. Precisely after 1 hour of dosing, blood samples were collected from marginal ear vein and rabbits were euthanized by intravenous injection of sodium pentobarbitone (150 mg/kg) via the marginal ear vein. Eyes were then enucleated immediately after euthanasia using surgical accessories and snap frozen immediately in dry ice:isopentane bath and stored at -80 °C until dissection. Eyes were dissected in frozen condition using dry ice:isopentane bath and a ceramic tile to avoid thawing during dissection. Various ocular tissues including cornea, conjunctiva, aqueous humor, iris-ciliary body, sclera, choroid-RPE, retina, lens, and vitreous humor were collected and transferred into labeled, preweighed tubes, tubes were reweighed and stored at -80 °C until further processing.

Tissue sample processing for LC-MS/MS analysis

Isolated ocular tissues were placed in glass tubes and mixed with 500 μl of water containing 500 ng/ml of moxifloxacin as an internal standard. Tissues were vortexed for 15 minutes on a multiple vortexer (VWR LabShop, Batavia, IL). Tissue samples were then homogenized using a homogenizer (Tissue-Tearor, Biospec Products, Bartlesville, OK) on an ice bath for 15 to 30 seconds such that the tissue was completely homogenized. Acetonitrile (1.5 ml) was added to the tissue homogenate and glass tubes were vortexed for 30 minutes. Extracted tissue homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min to separate the precipitated tissue proteins. The supernatant was pipetted out and transferred into clean glass tubes and evaporated under nitrogen stream (Multi-Evap; Organomation, Berlin, MA) at 40 °C. The residue after evaporation was reconstituted with 500 μl of acetonitrile:water (75:25 v/v) and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. In case of aqueous humor and vitreous humor samples were directly measured without extraction. Samples were diluted 5-fold with acetonitrile containing moxifloxacin as the internal standard, vortexed for 10 min and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 min. The supernatant (200 μl) was transferred into LC-MS/MS vials and subjected for analysis. The acetonitrile based extraction method for extraction of GFX and GFX prodrugs from rabbit ocular tissue was validated to determine the extraction recovery using three different concentrations (low, medium and high) to cover the entire range of expected concentrations of drug and prodrugs in various ocular tissues. Calibration curves for tissue sample analysis were developed in appropriate blank rabbit ocular tissue using 10 concentrations by spiking known amount of analytes and internal standard.

LC-MS/MS analysis

GFX and GFX prodrugs samples from in vitro transport study and in vivo delivery study were analyzed using validated LC-MS/MS method. API-3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) coupled with a PerkinElmer series-200 liquid chromatography (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) system was used for analysis. Chromatographic separation of GFX, GFX prodrugs, and internal standard moxifloxacin was performed on Obelisc C18 column (2.1 × 10 mm, 3 μm). Elution of analytes were performed using linear gradient elution with the mobile phase consisting of 5 mM ammonium formate (pH 3.5) and acetonitrile with a flow rate of 300 μl/minute and total run time of 6 minutes. All drugs, prodrugs and internal standard were analyzed in positive ionization mode with following multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions: 376 → 358 (GFX), 460.5 → 415 (DMAP-GFX), 461.4 → 358 (CP-GFX), 489.5 → 470.14 (APM-GFX), and 402.3 → 384.2 (moxifloxacin).

Data analysis

All values in this study are expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical comparison between two groups were determined using independent sample Student's t-test. One way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used if there were more than two groups. Differences were considered statistical significant at the level of p < 0.05.

Results

Synthesis and characterization of prodrugs

DMAP-GFX, CP-GFX and APM-GFX were synthesized using peptide chemistry. Amino group of gatifloxacin was protected using Boc-anhydride, sodium hydroxide as base in THF solvent. Once the amino group was protected, free carboxylic group of gatifloxacin was reacted with pro-moieties of DMAP-GFX and CP-GFX (3 and 6) using HBTU as coupling reagent. On the other hand, for synthesizing APM-GFX prodrug, carboxylic group was protected while the amino group was left free to react with leucine. The carboxylic acid group was protected as its methyl ester by conversion to the acid chloride with thionyl chloride and reaction with methanol. Free amino group available in the piperazine ring of gatifloxacin was coupled with carboxylic acid of Leucine. The overall yields of the prodrugs were 22%, 47%, and 55% for DMAP-GFX, CP-GFX, and APM-GFX, respectively. Identity and purity of the prodrugs was verified by proton NMR, mass spectrometry, and HPLC (Table 1). All of the prodrugs were analyzed under positive ion mode. Identity of the prodrugs was confirmed by HRMS, and the difference between the predicted and observed mass was less than 5 ppm (Table 1). All of the prodrugs were found to be more than 95 % pure (Table 1). Proton NMR spectra of the GFX prodrugs are described below:

Table 1.

Purity and identity of GFX prodrugs confirmed by HPLC and HRMS methods.

| Prodrug | Retention time (min) | Purity by HPLC | Predicted mass | Observed mass |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMAP-GFX | 14.25 | 96.12 % | 460.2724 | 460.2728 |

| CP-GFX | 16.48 | 98.9 % | 461.2200 | 461.2215 |

| APM-GFX | 21.77 | 95.08 % | 489.2513 | 489.2534 |

DMAP-GFX

1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) - δ 8.88 (s, 1H, Ar-H), δ 7.88 (d, J = 12.4 Hz, 1H, Ar-H), δ 4.17 (m, 1H, CH), δ 3.88 (s, 3H, CH3), δ 3.72-3.35 (m, 7H, 3 X CH2 and CH), δ 3.20 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H, CH2), δ 2.92 (s, 6H, 2 X CH3), δ 2.05 (m, 2H, CH2), δ 1.40 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H, CH3), δ 1.23 (m, 2H, CH2), δ 1.02 (m, 2H, CH2); Mass: 460.5 [M+H].

CP-GFX

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) – δ12.08 (s, 1H), δ 9.73 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), δ 8.65 (s, 1H), δ 7.74 (d, J = 12 Hz, 1H), δ 4.09 – 4.07 (m, 2H), δ 3.77 (s, 3H), δ 3.51 – 3.38 (m, 4H), 3.149 – 3.132 (m, 1H), δ 2.24 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), δ 2.17 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), δ 1.73 – 1.70 (m, 2H), 1.25 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 3H), 1.09-0.94 (m, 2H). Mass: 461.4 [M+H].

APM-GFX

1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD-d3) – δ 8.95 (d, 1H), δ 7.97 (d, 1H), δ 4.09 - 4.07 (m, 2H), δ 3.83 (s, 3H), 3.41 – 3.35 (m, 4H), δ 3.05 – 2.96 (m. 1H), δ 2.29 – 2.25 (m, 2H), 2.20 – 2.13 (m, 2H), 1.70 – 1.62 (m, 2H), 1.30 – 1.26 (m, 1H), 0.97 – 0.90 (m, 6H), 0.78 – 0.71 (m, 4H). Mass: 489.5 [M+H].

Solubility, pKa, and Log D (pH 7.4) of prodrugs

Solubility studies were performed for only 6 hours instead of 24 hours to prevent the influence of prodrug hydrolysis on the results of the solubility. We measured the buffer (pH 7.4) stability at 37°C for 24 hours and found that 9.51 %, 8.63 %, 8.97 % of GFX was formed from DMAP-GFX, CP-GFX, and APM-GFX, respectively. Solubility of gatifloxacin and its prodrugs was measured in water for injection (WFI, pH 6.4). When compared to solubility of gatifloxacin, solubility of DMAP-GFX prodrug increased from 0.007 M to 0.072 M (Table 1). At pH 6.4 (WFI), DMAP-GFX prodrug with two basic amino groups has the possibility to ionize better than GFX, thereby contributing to higher solubility. Solubility of CP-GFX and APM-GFX prodrugs did not improve (Table 2). In fact solubility of APM-GFX prodrug decreased from 0.007 M to 0.004 M. APM-GFX consisted of a primary amino group from leucine and a carboxylic acid group. APM-GFX prodrug essentially had similar ionizable moieties to that gatifloxacin, but it had a lipophilic isopropyl group from leucine contributing to lower solubility. Gatifloxacin is a zwitter ionic compound with an aliphatic secondary amino group and a carboxylic acid with measured pKa of 9.21 and 6.25, respectively (measured at 25 °C). Our measured values are close to that of the reported values for gatifloxacin (9.21- amino group, and 5.94 – carboxylic acid) 25. Gatifloxacin prodrugs exhibited higher Log D because ionizing functional groups were masked in each prodrug except CP-GFX (Table 2). Moreover, introduction of a propyl group in all prodrugs also contributed to increased Log D. Log D of DMAP-GFX, CP-GFX, APM-GFX were 0.05, 0.11, and 1.04, respectively. DMAP-GFX showed higher solubility and Log D than GFX. CP-GFX and APM-GFX prodrugs showed only improvement in Log D.

Table 2.

Measured values of solubility and Log D (pH 7.4) for gatifloxacin and its prodrugs. Data is expressed as mean ± SD for n = 3.

| Drug/Prodrug | Solubility (mg/ml)* | Solubility (M) | Log D (pH 7.4)# |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFX | 2.60 ± 0.3 | 0.007 | -1.15 |

| DMAP-GFX | 33.26 ± 3.0 | 0.072 | 0.05 ± 0.01 |

| CP-GFX | 3.01 ± 0.2 | 0.006 | 0.11 ± 0.01 |

| APM-GFX | 2.16 ± 0.3 | 0.004 | 1.04 ± 0.02 |

Solubility was performed in water for injection (pH 6.4).

Log D was performed in n-octanol and PBS buffer (pH 7.4).

In vitro transport and mechanisms for prodrugs

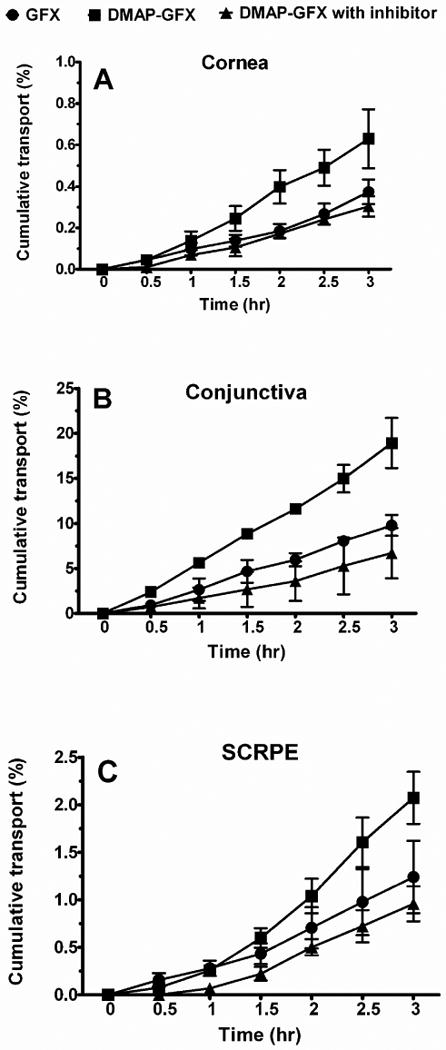

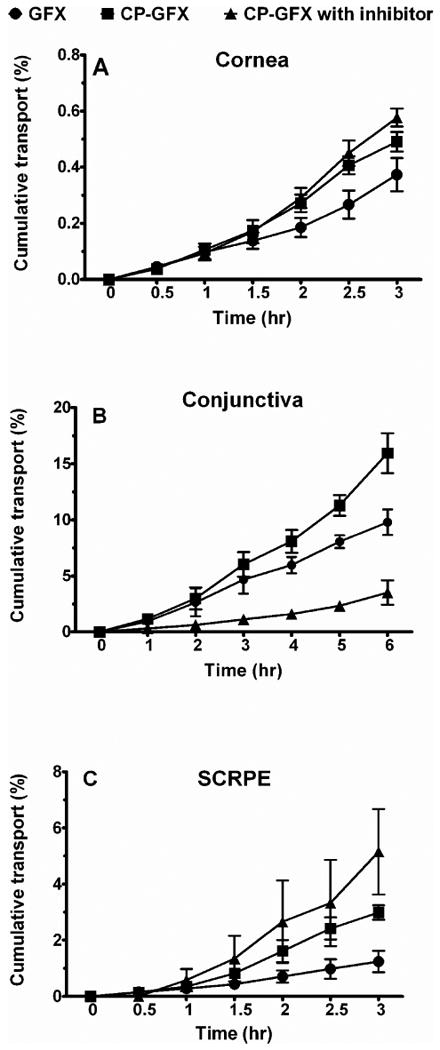

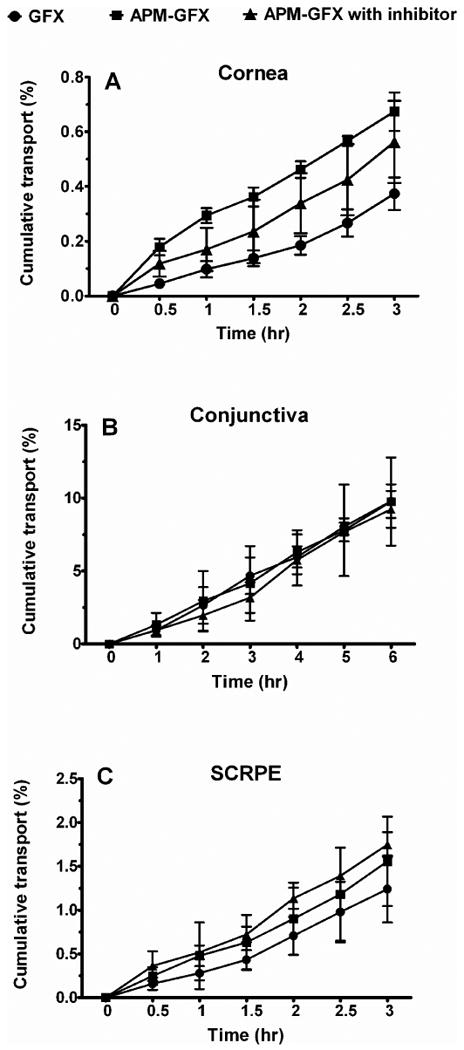

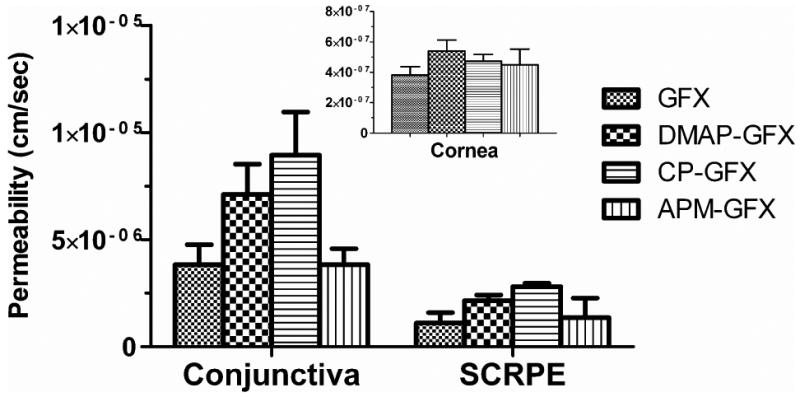

In vitro transport studies of GFX prodrugs were compared with GFX across rabbit (cornea and SCRPE) and bovine tissues (conjunctiva). For elucidating the mechanism of the prodrugs, transport was performed in the presence and absence of transporter specific inhibitors. Cumulative % transport of DMAP-GFX was significantly higher than GFX in all three tissues (p < 0.02, Figure 1). In addition, cumulative % transport was significantly lower (p < 0.009) in the presence of MPP+ (Figure 1). Thus, transport of DMAP-GFX was mediated by OCT transporter. Cumulative % transport of CP-GFX was significantly (p < 0.02) higher than GFX across all three tissues (Figure 2). In the presence of nicotinic acid (competitive inhibitor of MCT), cumulative % transport of CP-GFX was significantly reduced (p < 0.03) across conjunctiva, but it remained the same across cornea and SCRPE in the presence and absence of inhibitor (Figure 2). On the other hand, APM-GFX did not show any improvement in transport across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE, when compared to GFX (Figure 3). Moreover, in the presence of α-methyl-DL-tryptophan, APM-GFX did not show any change in transport indicating that it is not transported by ATB (0, +) transporter.

Figure 1.

Cumulative % transport of DMAP-GFX prodrug across a) cornea, b) conjunctiva, and c) SCRPE. Cornea and SCRPE were from NZW rabbit and conjunctiva was from bovine eyes. Cumulative % transport of DMAP-GFX was significantly increased across all tissues (p < 0.01), and DMAP-GFX transport was significantly inhibited by MPP+ across all tissues (p < 0.005). GFX levels formed in the prodrug group were below the detection limits. Data is expressed as mean ± SD for n = 4.

Figure 2.

Cumulative % transport of CP-GFX was significantly higher (p <0.01) than GFX across all tissues a) cornea, b) conjunctiva, and c) SCRPE. Cornea and SCRPE were from NZW rabbit and conjunctiva was from bovine eyes. CP-GFX transport was significantly inhibited by nicotinic acid (competitive inhibitor of MCT) across conjunctiva, but was not inhibited across cornea and SCRPE. GFX levels formed in the prodrug group were below the detection limits. Data is expressed as mean ± SD for n = 4.

Figure 3.

No improvement of cumulative % transport of APM-GFX prodrug in comparison to GFX across a) cornea, b) conjunctiva, and c) SCRPE. APM-GFX transport was not inhibited by α-methyl-DL-tryptophan (ATB inhibitor) across a) cornea and b) conjunctiva, and c) SCRPE. Cornea and SCRPE were from NZW rabbit and conjunctiva was from bovine eyes. GFX levels formed in the prodrug group were below the detection limits. Data is expressed as mean ± SD for n = 4.

In vivo ocular delivery of GFX and DMAP-GFX

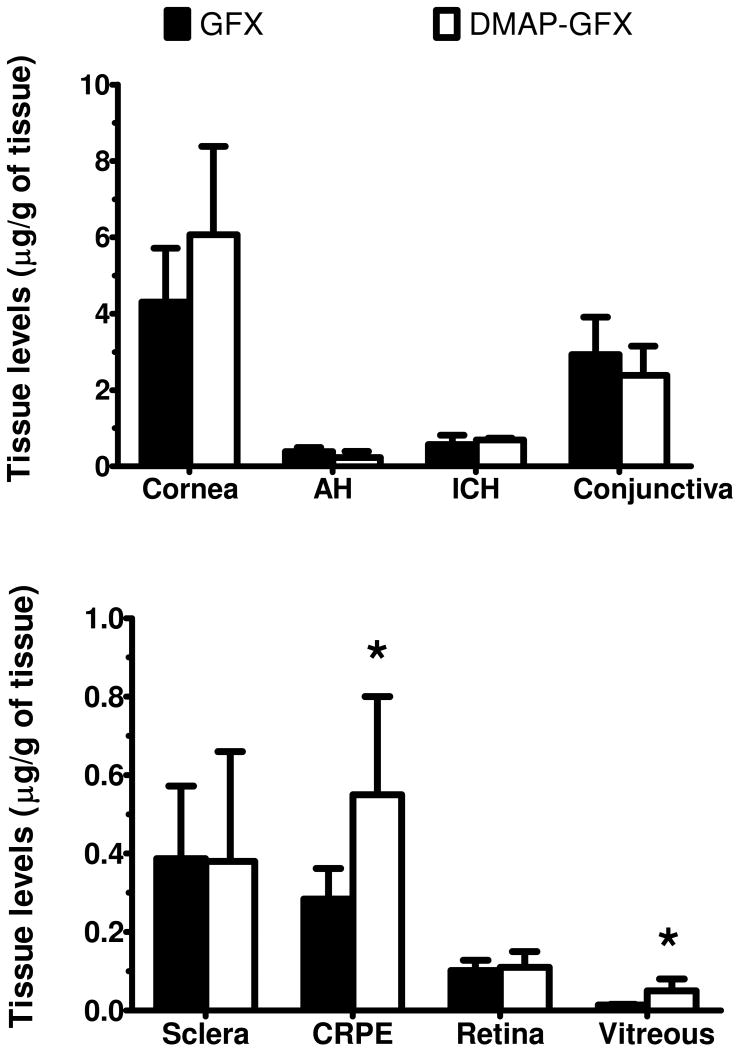

To evaluate whether in vitro transport differences can be translated to in vivo conditions, we compared the delivery of GFX and DMAP-GFX prodrug following topical eye drop dosing in pigmented rabbits. Prodrug and the parent drug formed were measured using LC-MS and reported as equivalents of prodrug (Figure 5). DMAP-GFX attained significantly (p < 0.02) higher levels in vitreous humor, and CRPE (Figure 5). In the remaining tissues, drug levels were not significantly different between drug and prodrug groups. Drug and prodrug levels were in the following order: cornea > conjunctiva > iris-ciliary body > CRPE ≥ aqueous humor ≥ sclera > retina > vitreous humor. DMAP-GFX prodrug improved the delivery of gatifloxacin to the back of the eye tissues.

Figure 5.

Ocular distribution of GFX and DMAP-GFX prodrug at 1 hour after their topical eye drop application in NZW pigmented rabbits. Levels of prodrug represent the sum of the GFX formed and unchanged prodrug in equivalents of prodrug. Vitreous levels were 3.6-fold higher with DMAP-GFX compared to GFX (* p < 0.05 calculated by Student's t-test). Data is expressed as mean ± SD for n = 4 animals.

In vivo bioconversion of DMAP-GFX prodrug

Tissue analysis at 1 hour after in vivo dose indicated conversion of prodrug in eye tissues, with the formed drug levels being 8, 70, 24, 13, 29, 13, 55, and 60 % of the total drug in cornea, conjunctiva, iris-ciliary body, aqueous humor, sclera, CRPE, retina, and vitreous humor, respectively (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Amount of GFX formed and DMAP-GFX prodrug remaining from in vivo ocular pharmacokinetics studies in pigmented rabbits at the end of 1 hour. Levels of the drug formed and prodrug in cornea and conjunctiva were plotted in the inset. Data is expressed as mean ± SD for n = 4.

Discussion

Delivery of antibiotics to the vitreous humor is crucial for treating bacterial endophthalmitis. Currently, systemic and intravitreal routes of administration are used to achieve required levels of antibiotics, but these routes are associated with their limitations. Topical eye drops is the most convenient and commonly used route for ophthalmic drugs; however, attaining therapeutic levels of antibiotics in the back of the eye is a major challenge. Several investigators reported the presence of influx transporters in ocular tissues, which can be potentially used to for targeted, enhanced delivery. In this study we designed and synthesized three prodrugs of gatifloxacin, in order to target transporters such as OCT, MCT, and ATB (0, +). In fact we are the first to develop ocular prodrugs for OCT and MCT transporters. DMAP-GFX prodrug exhibited higher transport across rabbit cornea and SCRPE, and bovine conjunctiva. CP-GFX also showed higher transport across all three tissues tested. In case of APM-GFX, we did not observe any improvement in transport across cornea and SCRPE compared to GFX, indicating that it is not being recognized by the ATB (0, +) transporter. Further, transport of DMAP-GFX was reduced by MPP+ (competitive inhibitor of OCT), indicating that it is transported by OCT transporter. All three GFX prodrugs showed higher Log D (pH 7.4) values. Only DMAP-GFX prodrug resulted in higher solubility (Table 2). Based on the in vitro transport and physicochemical properties, DMAP-GFX was further assessed in rabbits after topical dosing and determined that DMAP-GFX resulted in significantly higher delivery to the vitreous humor. Below, these findings are further elaborated.

Physicochemical properties of the prodrugs

Although our main focus was to improve the active transport of the drugs by targeting the membrane transporters, we also altered other properties that influence drug delivery such as solubility and Log D (pH 7.4). Higher solubility is a very useful property for topical eye drops because solubility of a drug molecule dictates the maximum strength of an ophthalmic solution formulation. With an increase in drug solubility, and hence, drug concentration of an ophthalmic solution, flux across ocular barriers is expected to increase. Introduction of pro-moiety with an ionizable group such as tertiary nitrogen, as is the case with DMAP-GFX, resulted in 10.2-fold higher solubility than GFX (Table 2). On the other hand solubility of CP-GFX and APM-GFX prodrugs were lower than that of gatifloxacin, which was due to the introduction of lipophilic propyl chain. Solubility of the prodrugs inversely correlated with Log D (pH 7.4). APM-GFX showed lowest solubility and highest Log D (Table 2). Prodrugs exhibited higher Log D because ionized functional groups were masked in each prodrug except CP-GFX. Promoieties in all three prodrugs consisted of 3- carbon chains, which increased the affinity of prodrugs towards the organic phase, thereby resulting in increased Log D for all three prodrugs.

Design and in vitro transport of prodrugs

Topically administered drugs have to cross cornea, conjunctiva, and RPE barriers before reaching the vitreous humor 26, 27. Ideally a prodrug targeting a membrane transporter present in all ocular barriers such as cornea, conjunctiva, and RPE will likely have the potential to deliver higher levels of drug to several intraocular tissues. Prodrugs were designed in this study using the information available in the literature including pharmacophore models, structure-activity-relationships for the binding of substrates to the transporters, and in vitro functional data.

OCT transports organic cation molecules with a transient or permanent charge at physiological pH 28. Cationic molecules that are comparatively elongated and planar with three hydrophobic masses are capable of interacting with the hydrophobic pocket of the OCT1 28. It is also known that hydrophobicity is an important determinant along with molecular size and shape in defining the interaction of the substrate with OCT2 transporter 29. The DMAP-GFX prodrug for the OCT transporter was obtained by coupling carboxyl group of gatifloxacin with amino group of the prodrug moiety via an amide bond. Prodrug moiety for OCT consisted of a cationic moiety (tertiary nitrogen) attached to a propyl chain (hydrophobic) (Scheme 1). DMAP-GFX prodrug had all the required features mentioned in the pharmacophore for OCT substrates 28, 29.

MCT transporter primarily transports lactic acid, which is a major end product of glucose metabolism 30. MCT transporter facilitates transport of a range of short-chain aliphatic monocarboxylic acids including both branched and unbranched 31. However, they do not transport dicarboxylic acids and tricarboxylic acids 32. Propanoic acid containing amino group was coupled to carboxylic group of gatifloxacin via amide bond (Scheme 1).

ATB (0, +) recognizes a broad spectrum of amino acids including neutral and cationic amino acids 33. In fact B0, + refers to broad including neutral and cationic amino acids. Mitra and co-workers developed the prodrugs of acyclovir targeting ATB (0, +) transporter 23, 34. APM-GFX prodrug was synthesized by linking carboxylic group of leucine with amino group of piperazine present in gatifloxacin.amino group was coupled to carboxylic group of gatifloxacin via amide bond (Scheme 1).

We chose to link the drug and promoieties via an amide linkage based on the fact that amide bonds are more stable than ester bonds, potentially maintaining them in intact form for transporter recognition during transit across multiple barriers including conjunctiva, sclera, choroid, and RPE, prior to entry into the vitreous humor.

We estimated the permeability of prodrugs across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE and determined that DMAP-GFX has 1.42-, 1.85-, and 1.95-fold improved permeability, respectively (Figure 4). CP-GFX prodrug showed 1.24-, 2.24-, and 1.82-fold higher permeability across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE, respectively (Figure 4). Surprisingly, there was no improvement in cumulative transport (%) of APM-GFX across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE in comparison to GFX (Figure 3). Upon further exploration of the lack of improvement in transport for APM-GFX prodrug, we learned that amidation (instead of esterification) of α-carboxyl group results in interference of the substrate binding with the ATB (0, +) transporter 35. Umapathy et al., showed that L-Valine, and esters of L-Valine (methyl and butyl) were transported via ATB (0, +) transporter. In contrast, amide of L-Valine (L-Valinamide) was not transported by ATB (0, +) transporter 35. Thus, esters but not amides of L-valine were recognized by ATB (0, +) transporter. In fact, Mitra and co-workers in the past have successfully developed prodrugs of acyclovir targeting ATB (0, +) transporter, and for this they linked the amino acids and acyclovir using an ester linkage 23. DMAP-GFX and CP-GFX resulted in higher transport across ocular tissues, but APM-GFX did not result in any improvement in the transport. DMAP-GFX has a solubility of 72 mM, which is 12- and 16-fold higher than CP-GFX (6.0 mM) and APM-GFX (4.0 mM), respectively. Flux of all prodrugs was tested at a similar concentration of 200 μM in this study. We believe that DMAP-GFX is being tested at a much lower chemical potential than the other two prodrugs and hence its absolute performance could be even better than the data indicate.

Figure 4.

Permeability coefficients of gatifloxacin prodrugs in comparison to gatifloxacin across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE tissues. Cornea and SCRPE were from NZW rabbit and conjunctiva was isolated from bovine eyes. Data is expressed as mean ± SD for n = 4.

Mechanism of prodrug transport

In order to determine the role of transporters in higher delivery of prodrugs, we studied transport of prodrugs in the presence of transporter specific inhibitors. MPP+ is commonly used to competitively inhibit transport mediated by OCT. It has been to shown to inhibit OCT1, OCT2 and OCT3 transporters 36. In the presence of MPP+, transport of DMAP-GFX was inhibited across all tissues (Figure 1). Cumulative transport (%) of DMAP-GFX was significantly reduced in the presence of OCT inhibitor and its permeability in the absence of inhibitor was 1.42, 2.15-, and 2.06-fold higher across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE (Figure 1), respectively, when compared to GFX, indicating transporter mediated transport of DMAP-GFX.

Nicotinic acid is known to competitively inhibit transport mediated by MCT transporter 37. In case of CP-GFX, we observed contrasting results in different tissues in the presence of inhibitor on both donor and receiver side. Transport of CP-GFX across conjunctiva was significantly lower in the presence of nicotinic acid (Figure 2), indicating that the transport was mediated by MCT. On the other hand, transport of CP-GFX across cornea and SCRPE was unchanged in the presence of nicotinic acid (Figure 2). To explain the lack of inhibition in cornea and SCRPE, we explored the literature and found that nicotinic acid also inhibits OATP-B transporter 38. mRNA expression of OATP-1A2 and OATP-2B1 efflux transporters was reported in human cornea and choroid/retina 18. Based on these results and literature reports, we speculate that CP-GFX is transported by OATP-2B1. This may have resulted in two opposite phenomena taking place simultaneously in the presence of nicotinic acid, inhibition of prodrug influx by MCT transporter, and inhibition of prodrug efflux by OATP transporter.

α-Methyl-DL-tryptophan is a specific inhibitor of ATB (0, +) transporter 39. In the presence of ATB (0, +) inhibitor, APM-GFX prodrug permeability was unchanged across cornea, conjunctiva, and SCRPE (Figure 3). Thus, APM-GFX prodrug does not appear to be a substrate for ATB (0, +) transporter. Thus, using transporter inhibitors, we showed that transport of DMAP-GFX and CP-GFX was mediated by OCT and MCT, respectively.

In vivo bioconversion of DMAP-GFX prodrug

A prodrug needs to exhibit optimum stability to achieve transporter mediated delivery advantage. It should not be cleaved rapidly so that it can be recognized by transporters present in barriers such as cornea, conjunctiva, and RPE. At the same time, the prodrug should be converted back to the parent drug in target tissues to exert its efficacy. After topical dosing, prodrug needs to cross conjunctiva, SCRPE, and retina to reach the vitreous humor. Vitreous is made up of water (98%) with very small amount of proteins, collagen, and hyaluronic acid and it is largely devoid of cells. Therefore, enzymatic conversion of prodrug to drug in vitreous is expected to be less compared to other tissues 40. Drug concentration observed in vitreous is most likely due to conversion of prodrug to drug in conjunctiva, choroid-RPE, and retina. Amount of drug:prodrug ratio in vitreous humor was found to be 60:40, indicating that the prodrug showed reasonable stability before reaching the target tissues. Although we have not identified the metabolic enzymes involved in bioconversion of prodrug to drug, based on prodrug chemistry we speculate that amidases, CYP450, and esterases are involved in bioconversion of prodrug to drug. In our previous report on celecoxib amide prodrugs, we showed that amide prodrugs are metabolized by esterases, amidases, and CYP450 enzymes that are present in both ocular tissues and plasma 41.

Interestingly, we did not observe any significant conversion of the prodrug during in vitro transport study. However, we observed significant conversion during in vivo studies. We speculate that this discrepancy is partly due to two important differences between the in vitro and in vivo study. First, the area of ocular tissues exposed during transport studies (0.64 cm2) is much less than what was available during in vivo studies. Topical eye drop in a rabbit is exposed to cornea, which occupies 1.55 ± 0.19 cm2 and conjunctiva, which occupies about 13.34 ± 1.63 cm2 42. Second, there is a difference in the availability of co-substrates for enzymatic conversion between in vitro and in vivo study. We recently reported that eye tissues metabolize amide prodrugs via multiple pathways including CYP450 enzymes 41, which require co-substrates such as NADPH for metabolism. Assay buffer (pH 7.4) used in this study for permeability experiments did not have NADPH or NADPH regenerating system.

Comparison of in vivo delivery of GFX and DMAP-GFX prodrug

We measured the in vivo delivery of DMAP-GFX prodrug to determine whether the higher in vitro transport across all tissues can be translated to the in vivo setting. Moreover, we wanted to take the advantage of higher solubility of DMAP-GFX. DMAP-GFX was dosed at approximately seven times higher concentration than GFX. We expected to see higher delivery of DMAP-GFX across all ocular tissues. However, we found 1.95- and 3.6-fold higher levels only in CRPE and vitreous humor with DMAP-GFX (Figure 5). In all remaining tissues, drug and prodrug dosing resulted in more or less similar delivery. In our in vivo studies, we collected the ocular tissues at 1 hour that corresponds to the Tmax of GFX in vitreous humor following a single eye drop study in pigmented rabbits 43. However, Tmax of GFX is different for different ocular tissues following topical eye drop dosing in rabbits 43. The reported Tmax was 0.083 h for cornea, conjunctiva, tear fluid, and plasma. The reported Tmax for aqueous humor was 0.33 h 43. In case of vitreous humor, we observed 3.6-fold greater delivery with prodrug when compared to gatifloxacin drug dosing. In the NDA submitted by Allergan for gatifloxacin, the influence of dose on pharmacokinetics and delivery of GFX (21-493, www.fda.gov/cder/) was assessed. In the studies supporting the NDA, there were no significant differences in GFX levels in cornea, conjunctiva, and aqueous humor between the 0.3% and 0.5% gatifloxacin groups. However, the sponsors suggested a role for pH differences in the formulation (0.3% was formulated at pH 6.0 and 0.5 % was formulated at pH 5.5) for the observations. Previously our laboratory has investigated the ocular pharmacokinetics of gatifloxacin dendrimer complex (DPT-GFX 1.2%) and compared the results with NDA (21-493) studies of gatifloxacin (0.1%, 0.3 %, and 0.5 %) 44. At 1 hour, levels of gatifloxacin in DPT-GFX and 0.3% or 0.5 % gatifloxacin groups were not significantly different in cornea, conjunctiva, and aqueous humor. However, area under the curve was significantly higher in cornea (2.6-fold), conjunctiva (11.9-fold), and aqueous humor (3.75-fold). Based on the Tmax, DPT-GFX data, and lack of dose proportionate increase in delivery of gatilfoxacin above 0.3% dose, we conclude that higher delivery in vitreous humor and CRPE may be because of the improved permeability of the prodrug.

Concusions

We successfully developed gatifloxacin prodrugs with enhanced solubility and transporter mediated permeability, resulting in higher delivery to the vitreous humor. Modification of prodrugs via amide bond provides adequate enzymatic stability for the prodrugs before they reach the posterior tissues. While the prepared amide prodrugs were useful for OCT and potentially MCT mediated delivery, they did not improve ATB (0, +) transporter mediated delivery.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH grants EY018940 and EY017533.

References

- 1.Callegan MC, Engelbert M, Parke DW, 2nd, Jett BD, Gilmore MS. Bacterial endophthalmitis: epidemiology, therapeutics, and bacterium-host interactions. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15(1):111–24. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.111-124.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams A, Sloan FA, Lee PP. Longitudinal rates of cataract surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(9):1308–14. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.9.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lalwani GA, Flynn HW, Jr, Scott IU, Quinn CM, Berrocal AM, Davis JL, Murray TG, Smiddy WE, Miller D. Acute-onset endophthalmitis after clear corneal cataract surgery (1996- 2005). Clinical features, causative organisms, and visual acuity outcomes. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(3):473–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keay L, Gower EW, Cassard SD, Tielsch JM, Schein OD. Postcataract Surgery Endophthalmitis in the United States Analysis of the Complete 2003 to 2004 Medicare Database of Cataract Surgeries. Ophthalmology. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhavsar AR, Ip MS, Glassman AR. The risk of endophthalmitis following intravitreal triamcinolone injection in the DRCRnet and SCORE clinical trials. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(3):454–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhavsar AR, Googe JM, Jr, Stockdale CR, Bressler NM, Brucker AJ, Elman MJ, Glassman AR. Risk of endophthalmitis after intravitreal drug injection when topical antibiotics are not required: the diabetic retinopathy clinical research network laser-ranibizumab-triamcinolone clinical trials. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(12):1581–3. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai YY, Tseng SH. Risk factors in endophthalmitis leading to evisceration or enucleation. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2001;32(3):208–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Recchia FM, Busbee BG, Pearlman RB, Carvalho-Recchia CA, Ho AC. Changing trends in the microbiologic aspects of postcataract endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(3):341–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferencz JR, Assia EI, Diamantstein L, Rubinstein E. Vancomycin concentration in the vitreous after intravenous and intravitreal administration for postoperative endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(8):1023–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.8.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiechens B, Neumann D, Grammer JB, Pleyer U, Hedderich J, Duncker GI. Retinal toxicity of liposome-incorporated and free ofloxacin after intravitreal injection in rabbit eyes. Int Ophthalmol. 1998;22(3):133–43. doi: 10.1023/a:1006137100444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mather R, Karenchak LM, Romanowski EG, Kowalski RP. Fourth generation fluoroquinolones: new weapons in the arsenal of ophthalmic antibiotics. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(4):463–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01334-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson R. Zymar as an ocular therapeutic agent. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2006;46(4):73–84. doi: 10.1097/01.iio.0000212138.62428.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen MK, Fiscella RG, Moshirfar M, Mooney B. Third- and fourth-generation fluoroquinolones: retrospective comparison of endophthalmitis after cataract surgery performed over 10 years. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(9):1460–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stern M, Jianping G, Beurman R, William F, Zhou L, McDonell PP, S Effects of Fourth-Generation Fluoroquinolones on the Ocular Surface, Epithelium, and Wound Healing. Cornea. 2006;25(9):S12. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hariprasad SM, Mieler WF, Holz ER. Vitreous and aqueous penetration of orally administered gatifloxacin in humans. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(3):345–50. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biggs WS. Hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia associated with gatifloxacin use in elderly patients. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(5):455–7. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.5.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costello P, Bakri SJ, Beer PM, Singh RJ, Falk NS, Peters GB, Melendez JA. Vitreous penetration of topical moxifloxacin and gatifloxacin in humans. Retina. 2006;26(2):191–5. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200602000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang T, Xiang CD, Gale D, Carreiro S, Wu EY, Zhang EY. Drug transporter and cytochrome P450 mRNA expression in human ocular barriers: implications for ocular drug disposition. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36(7):1300–7. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.021121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajan PD, Kekuda R, Chancy CD, Huang W, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Expression of the extraneuronal monoamine transporter in RPE and neural retina. Curr Eye Res. 2000;20(3):195–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chidlow G, Wood JP, Graham M, Osborne NN. Expression of monocarboxylate transporters in rat ocular tissues. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288(2):C416–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00037.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philp NJ, Wang D, Yoon H, Hjelmeland LM. Polarized expression of monocarboxylate transporters in human retinal pigment epithelium and ARPE-19 cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(4):1716–21. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatanaka T, Haramura M, Fei YJ, Miyauchi S, Bridges CC, Ganapathy PS, Smith SB, Ganapathy V, Ganapathy ME. Transport of amino acid-based prodrugs by the Na+- and Cl(-) - coupled amino acid transporter ATB0,+ and expression of the transporter in tissues amenable for drug delivery. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308(3):1138–47. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jain-Vakkalagadda B, Pal D, Gunda S, Nashed Y, Ganapathy V, Mitra AK. Identification of a Na+-dependent cationic and neutral amino acid transporter, B(0,+), in human and rabbit cornea. Mol Pharm. 2004;1(5):338–46. doi: 10.1021/mp0499499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kadam RS, Cheruvu NP, Edelhauser HF, Kompella UB. Sclera-choroid-RPE transport of eight beta-blockers in human, bovine, porcine, rabbit, and rat models. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(8):5387–99. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.BMS. New Drug Application for Tequin (21-061/SE-007) 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenwald RD, Deshpande GS, Rethwisch DG, Barfknecht CF. Penetration into the anterior chamber via the conjunctival/scleral pathway. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 1997;13(1):41–59. doi: 10.1089/jop.1997.13.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed I, Patton T. Disposition of timolol and inulin in rabbit eye following corneal versus non-corneal absorption. Internation Journal of Pharmaceutics. 1987;38:9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bednarczyk D, Ekins S, Wikel JH, Wright SH. Influence of molecular structure on substrate binding to the human organic cation transporter, hOCT1. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63(3):489–98. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suhre WM, Ekins S, Chang C, Swaan PW, Wright SH. Molecular determinants of substrate/inhibitor binding to the human and rabbit renal organic cation transporters hOCT2 and rbOCT2. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67(4):1067–77. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poole RC, Halestrap AP. Transport of lactate and other monocarboxylates across mammalian plasma membranes. Am J Physiol. 1993;264(4 Pt 1):C761–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.4.C761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole RC, Cranmer SL, Halestrap AP, Levi AJ. Substrate and inhibitor specificity of monocarboxylate transport into heart cells and erythrocytes. Further evidence for the existence of two distinct carriers. Biochem J. 1990;269(3):827–9. doi: 10.1042/bj2690827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Broer S, Schneider HP, Broer A, Rahman B, Hamprecht B, Deitmer JW. Characterization of the monocarboxylate transporter 1 expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes by changes in cytosolic pH. Biochem J. 1998;33(Pt 1):167–74. doi: 10.1042/bj3330167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ganapathy ME, Ganapathy V. Amino Acid Transporter ATB0,+ as a delivery system for drugs and prodrugs. Curr Drug Targets Immune Endocr Metabol Disord. 2005;5(4):357–64. doi: 10.2174/156800805774912953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anand BS, Katragadda S, Nashed YE, Mitra AK. Amino acid prodrugs of acyclovir as possible antiviral agents against ocular HSV-1 infections: interactions with the neutral and cationic amino acid transporter on the corneal epithelium. Curr Eye Res. 2004;29(2-3):153–66. doi: 10.1080/02713680490504614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Umapathy NS, Ganapathy V, Ganapathy ME. Transport of amino acid esters and the amino-acid-based prodrug valganciclovir by the amino acid transporter ATB(0,+) Pharm Res. 2004;21(7):1303–10. doi: 10.1023/b:pham.0000033019.49737.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonker JW, Schinkel AH. Pharmacological and physiological functions of the polyspecific organic cation transporters: OCT1, 2, and 3 (SLC22A1-3) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;308(1):2–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuji A, Takanaga H, Tamai I, Terasaki T. Transcellular transport of benzoic acid across Caco-2 cells by a pH-dependent and carrier-mediated transport mechanism. Pharm Res. 1994;11(1):30–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1018933324914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi D, Nozawa T, Imai K, Nezu J, Tsuji A, Tamai I. Involvement of human organic anion transporting polypeptide OATP-B (SLC21A9) in pH-dependent transport across intestinal apical membrane. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306(2):703–8. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.051300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karunakaran S, Umapathy NS, Thangaraju M, Hatanaka T, Itagaki S, Munn DH, Prasad PD, Ganapathy V. Interaction of tryptophan derivatives with SLC6A14 (ATB0,+) reveals the potential of the transporter as a drug target for cancer chemotherapy. Biochem J. 2008;414(3):343–55. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Malson Gel of crosslinked hyaluronic acid for use as vitreous humor substitute. 4,716,154, 1987

- 41.Malik P, Kadam RS, Cheruvu NP, Kompella UB. Hydrophilic prodrug approach for reduced pigment binding and enhanced transscleral retinal delivery of celecoxib. Mol Pharm. 2012;9(3):605–14. doi: 10.1021/mp2005164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 42.Watsky MA, Jablonski MM, Edelhauser HF. Comparison of conjunctival and corneal surface areas in rabbit and human. Curr Eye Res. 1988;7(5):483–6. doi: 10.3109/02713688809031801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Proksch JW, Ward KW. Ocular pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of besifloxacin, moxifloxacin, and gatifloxacin following topical administration to pigmented rabbits. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2010;26(5):449–58. doi: 10.1089/jop.2010.0054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durairaj C, Kadam RS, Chandler JW, Hutcherson SL, Kompella UB. Nanosized dendritic polyguanidilyated translocators for enhanced solubility, permeability, and delivery of gatifloxacin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(11):5804–16. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]