Abstract

To analyze the short-term effects of a proprioceptive session on the monopodal stabilometry of athletes. [Subjects] Thirty-seven athletes were divided into a control group (n=17) and an experimental group (n=20). [Methods] Both groups performed a conventional warm-up, after which a 25-minute proprioceptive session on ustable platforms was carried out only by the experimental group. Before the training session, all athletes carried out a single-leg stabilometry test which was repeated just after training, 30 minutes, 1 hour, 6 hours and 24 hours later. [Results] Analysis of covariance (α=0.05) revealed that the experimental group had lower values than the control group in length and velocity of center of pressure (CoP) of left-monopodal stance and in velocity of CoP of right-monopodal stance in post-training measurements. Also, the experimental group had values closer to zero for the CoP position in the mediolateral and anteroposterior directions of left-monopodal stance (Xmeanl and Ymeanl) and the anteroposterior direction in on right-monopodal stance (Ymeanr) in post-training measurements. Within-group analysis of Xmeanl and Ymeanl, length and velocity of CoP in right-monopodal stance showed continuous fluctuations of values between sequential measurements in the control group. [Conclusion] Proprioceptive training on unstable platfoms after a warm-up stabilizes the position of CoP in the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions and decreases CoP movements in short-term monopodal stability of athletes.

Key words: Proprioception, Athletes, Stabilometry

INTRODUCTION

Monopodal postural stance and proprioception are very important parameters in the functionality of the lower limbs of athletes1). In sports, fatigue and stress along with injuries, contribute to the deterioration of the proprioceptive sense. All these aspects put athletes at risk of possible relapses or new injuries2,3,4). Training on unstable platforms has become a common tool in several sports to reduce injury risks of athletes, and to help them improve their proprioceptive sense5).

Proprioceptive training on unstable platforms has been shown to result in large and medium-to-long term improvement when practiced for several consecutive weeks. Its benefits appear mainly in stabilometric parameters6,7,8,9). Several authors have stated that an improvement in postural stability provides athletes with a much more stable basic stance, from which they can perform movements in a stronger and more precise fashion10). Romero-Franco et al. showed there were significant improvements in postural stability as well as in the control of the center of gravity after a six-week proprioceptive training program9). Similarly, Stanton et al. and Mattacola and Lloyd observed an improvement in static balance and dynamic balance variables, respectively, after proprioceptive training6, 7). Others surveys have tested the monopodal stability of athletes due to the fact that it is a more specific analysis, and therefore more fitting to the needs of their particular sport of choice. The research carried out by Paterno et al. is a good example of this. They observed that a six-week proprioceptive training program improved not only general monopodal postural stance but also the values of center of pressure position in the anteroposterior direction, which reduced the number of ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) injuries in the long term1).

Until now, proprioceptive training studies have mainly dealt with medium- and long-term effects, while short-term effects have received little attention. Some authors have analyzed muscle activation using EMG under conditions of instability, and have reported sizeable immediate increases in muscle activities11,12,13,14). It is believed that this increase aims to stabilize and maintain the gravity center, thus avoiding a potential fall4, 15). However, a consequence of this muscle activity increase compensating for the instability condition, is that athletes experience a great diminution of force output.

In spite of evidence about the improvement provided by proprioceptive training, studies to date have not investigated on the short-term stabilometric effects that come from proprioceptive training. The study of Romero-Franco et al. is the only study, to our knowledge, that has analyzed the short-term stabilometric effects of training on unstable platforms. In that study, measurements were taken inmediately after proprioceptive training, and the results which showed worse bipodal postural stability of the athletes. This decrease may have been a consequence of fatigue, according to the authors16).

With so little scientific evidence it is difficult to know the immediate results of proprioceptive training. This would be of great importance for determining when, during the training process, such exercises should take place. The purpose of this study was to analyze the short-term effects of a proprioceptive training session on an unstable platform on the monopodal stabilometry of athletes. Based on previous reports of a great increase in muscle activity with a consequent loss of force under unstable conditions, and immediate adverse effects on bipodal stability, of proprioceptive training, we authors hypothesized that proprioceptive training would negatively affect athletes’ monopodal stabilometry.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

A 24-hour quasi-experimental study was carried out in March 2012 with 6 repeated measurements of the monopodal stance:

Pre (pre-training), Post0Min (right after training), Post30Min (30 minutes after training), Post1H (1 hour after training), Post6H (6 hours after training) y Post24H (24 hours after training).

Subjects

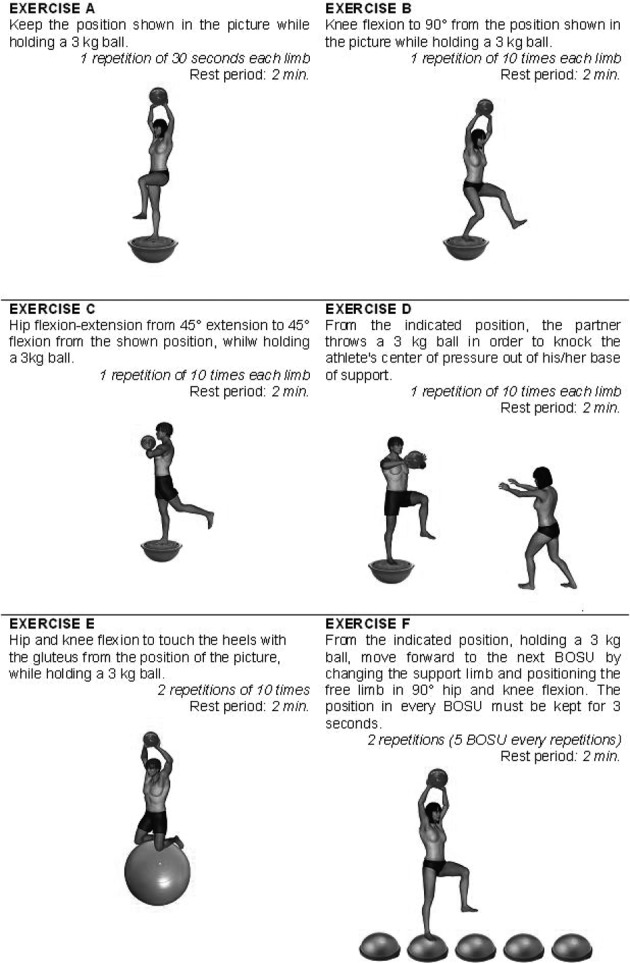

We selected thirty-seven athletes who volunteered for this experiment (Table 1) and randomly divided them into two groups: the Control Group (CG) comprised 17 athletes who carried out a 25-minute conventional warm up, and the Experimental Group (EG), comprised 20 athletes who carried out the same warm up and then performed a 25-minute proprioceptive training session on unstable platforms (Fig 1). We excluded subjects who usually performed proprioceptive exercises, in addition to those who were injured at the time of the study. Before the start, we briefed all the athletes about the test and about the nature of proprioceptive training. In addition, we obtained written informed consent from each subject or their legal guardians in the case of underage athletes, according to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki17). The ethical committee of the University of Jaén approved the study.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and anthropometric characteristics.

| All | n=37 | Control | n=17 | Experimental | n=20 | ||

| Age (y) | 21.2 | ±4.6 | 21.1 | ±4.9 | 21.3 | ±4.5 | |

| Height (cm) | 173.9 | ±6.9 | 172.4 | ±6.9 | 175.1 | ±6.9 | |

| Weight (kg) | 63.7 | ±11.7 | 61.3 | ±12.9 | 65.7 | ±10.5 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.9 | ±2.7 | 20.5 | ±2.8 | 21.4 | ±2.7 | |

| Gender | Woman | 12 | 32.40% | 7 | 41.20% | 5 | 25.00% |

| Man | 25 | 67.60% | 10 | 58.80% | 15 | 75.00% | |

| Student | Yes | 25 | 67.60% | 14 | 82.40% | 11 | 55.00% |

| No | 12 | 32.40% | 3 | 17.60% | 9 | 45.00% | |

Quantitative variables are shown as mean and SD. Categorical variables are shown as frequencies and percentages. BMI, Body Mass Index.

Fig. 1.

Proprioceptive training session which the experimental group carried out (Designed and conducted by authors).

Methods

We used Five BOSU® Balance Trainers, five Swiss balls and five 3 kg medicine balls for the proprioceptive training session. We determined the correct diameter of the Swiss ball by measuring the height of each athlete: when athletes were sitting on the ball, their knees and hips had to be flexed at 90°18). A FreeMed© BASE model baropodometric platform was used for the stabilometric measurements (Rome, Italy). The platform’s surface is 555 × 420 mm, with an active surface of 400 × 400 mm and 8 mm thickness, (Sensormédica® Sevilla, Spain). The reliability of this baropodometric platform has been shown in previous studies16). Calculations of center-of-pressure (CoP) movements were performed with the FreeStep© Standard 3.0 (Italy) software. We collected baseline features of the athletes with a 100 g–300 kg precision digital weight scale (Tefal) and a t201-t4 Asimed adult height scale to obtain weight and height respectively (Table 1).

To carry out the monopodal stabilometric measurement, we asked the athletes to stand for fifteen seconds on each lower limb, starting with the left one, in the middle of the platform. The athletes stood without shoes with both arms at the sides of the body and the non-support leg in 90° of knee flexion. Also, we asked athletes not to engage in any physical activity for the duration of the study.

The stabilometry test measured the following parameters of both the left- and right-leg stances: the center of pressure (CoP) position in the mediolateral (Xmean) and anteroposterior directions (Ymean), in addition to the length (Length) and the area (Area) covered by the CoP and the velocity (Velocity) of CoP movement. These variables are suffixed with “l” or “r” to indicate whether they belong to the left or right leg, respectively.

First, all athletes completed the pre-training stabilometry test. After those measurements, a 25-minute conventional warm-up was carried out by all athletes. The warm-up consisted of 10 minutes of slow running, 5 minutes of dynamic stretching and 10 minutes of specific running exercises. After the warm-up, the experimental group also performed the 25-minute proprioceptive training session (Fig. 1).

The 25-minute proprioceptive training session consisted of 6 Swiss ball and BOSU exercises and the correct performance of the exercises was carefully supervised by a fitness specialist and a sports physiotherapist, who worked with groups of 10 to 12 athletes. The effects of this type of training are based on disturbances caused under unstable conditions, which force the center of pressure out of the support base. To avoid a potential fall, stabilizing musculature is activated to make postural adjustments and maintain the center of pressure within the support base19). These postural adjustments and neural adaptations are the main responsible of benefits of proprioceptive training appearing in stabilometric parameters6,7,8,9).

Just after the warm-up, in the case of the control group, and immediately after the proprioceptive session in the case of the experimental group, the Post0Min measurements were taken. Post30Min measurements were taken 30 minutes later and Post1H measurements were taken one hour after the proprioceptive session. Post6H was measured after 6 hours, and Post24H, at 24 hours after the proprioceptive training session.

Descriptive statistics include averages and standard deviations for the continuous variables, and the frequencies and percentages of the categorical variables (Table 1). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test the normal distribution of quantitative variables. Regarding the demographic and morphological variables, Student’s t test was used for independent samples in the case of the continuous variables and the c2 test for the categorical variables. The general linear repeated measures model was employed for all variables, with time and intervention group as within- and between-subjects variables, respectively (repeated measures ANOVA). A covariance analysis was performed on variables showing differences from baseline, with the initial measurement as covariate (ANCOVA). The level of statistical significance used was p <0.05. Data analysis was performed by means of the SPSS statistical data analysis package for Windows (v.19; Chicago).

RESULTS

Table 1 shows socio-demographic and morphological variables related to the sample as well as the differences between the experimental and control groups. No significant difference was noted (p>0.05).

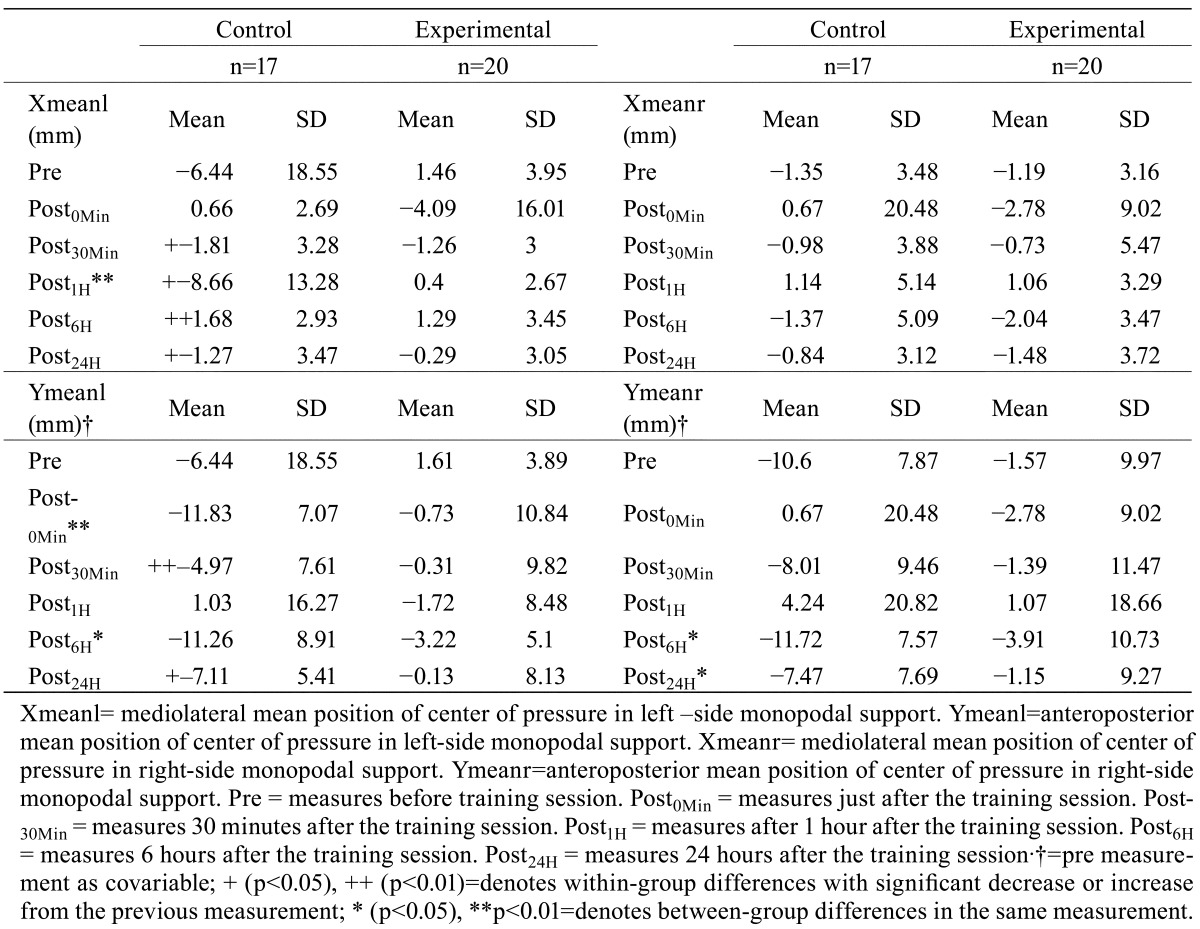

The mean CoP position in the mediolateral (Xmeanl and Xmeanr) and the anteroposterior (Ymeanl and Ymeanr) directions of both monopodal supports are shown in Table 2. Xmeanl showed a statistically significant group*time interaction (p=0.002). Within-group analysis showed that the control group experienced a significant decrease at Post30Min from 0.66±2.69 at baseline to −1.81±3.28 mm (p=0.024), another significant decrease at Post1H from 1.81±3.28 to −8.66±13.28 mm (p=0.042), an increase at Post6H from −8.66±13.28 to 1.68±2.93 mm (p=0.008) and a decrease at Post24H from 1.68±2.93 to −1.27±3.47 mm (p=0.013). Meanwhile, the experimental group showed similar values for all measurements with no significant differences (p>0.05). Also, between-group analysis showed significant differences at Post1H, when the control group had values further from zero than the experimental group (−8.66±13.28 vs 0.40±2.67 mm, p=0.005).

Table 2. Mean values of variables of center of pressure position in mediolateral (Xmean) and anteroposterior (Ymean) directions.

Ymeanl showed a main time effect (p=0.042) and a statistically significant group*time interaction (p=0.043). In within-group analysis, the control group showed an increase at Post30Min from −11.83±7.07 at baseline to −4.97±7.61 mm (p=0.005), and another increase at Post24H from −11.26±8.91 to −7.11±5.41 mm (p=0.015), while the experimental group showed similar values for all measurements with no significant differences (p>0.05). Furthermore, between-group analysis showed significant differences at Post0Min and Post6H, when the experimental group had values nearer to zero that the control group (−11.83±7.07 vs −0.73±10.84 mm, p=0.009 and −11.26±8.91 vs −3.22±5.10 mm, p=0.036, respectively).

Ymeanr showed a main time effect (p=0.003) and a non-significant group*time interaction, (p=0.052). Between-group analysis showed statistically significant diferences at Post6H (p=0.017) when the control group had values further from zero than the experimental group (−11.72±7.57 vs −3.91±10.73 mm). Similar results were observed at Post24H, with values further from zero than the control group (−7.47±7.69 vs −1.15±9.27 mm, p=0.032). Also, results close to the level of significance (p=0.066) were found at Post30Min when the control group had values further from zero than the experimental group (−8.01±9.46 vs −1.39±11.47 mm). Within-group analysis did not find any significant result. The other variables did not show any significant group*time interactions (p>0.05).

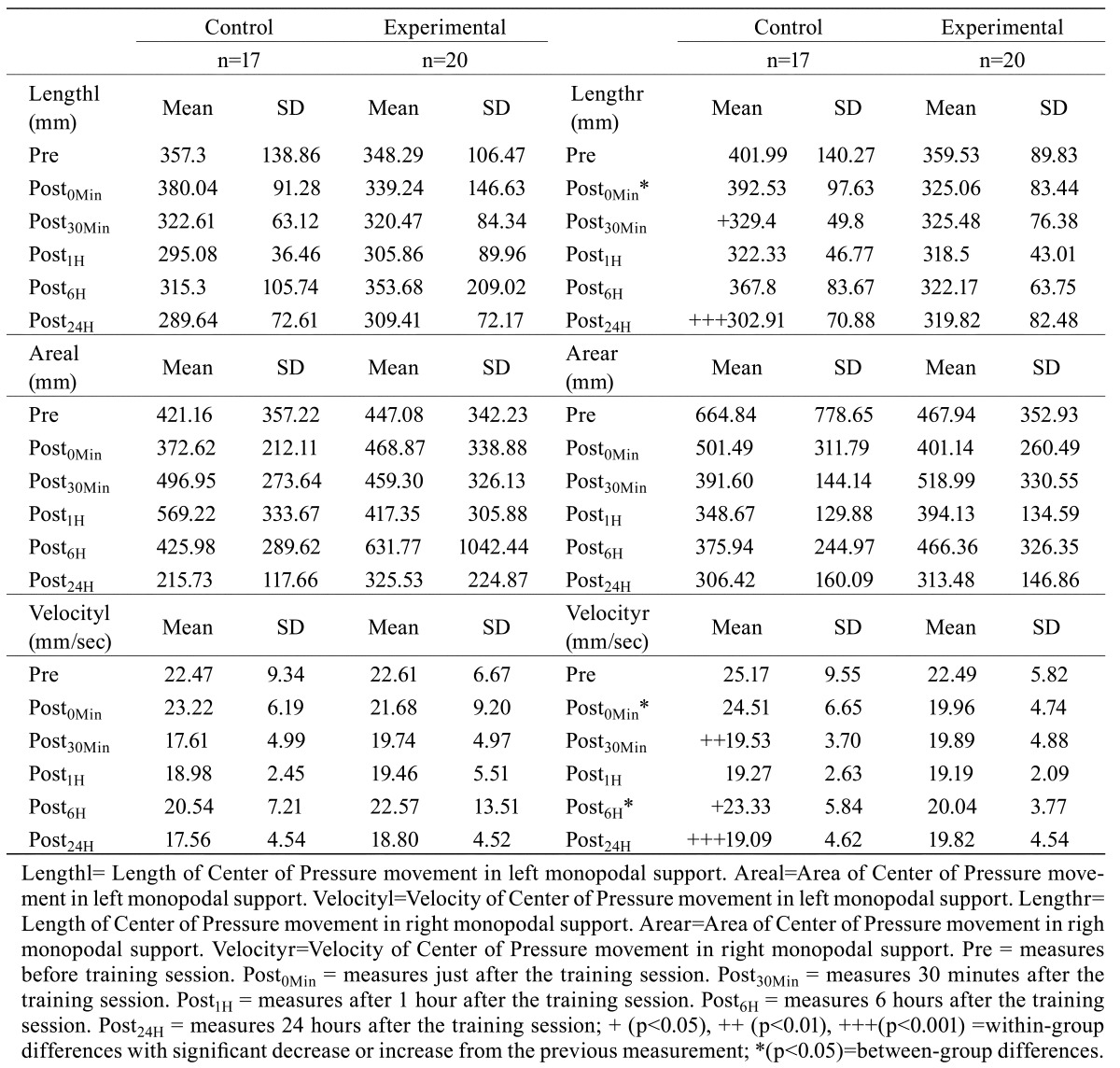

Length and Area covered by CoP (Lengthl and Lengthr, Areal and Arear) and Velocity of CoP movement (Velocityl and Velocityr) are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Mean values of variables of CoP movement (Length, Area, Velocity) in both left-side and right-side monopodal supports.

Lengthr showed a main time effect (p<0.001) and a statistically significant group*time interaction (p=0.048). Within-group analysis showed that the control group experienced a decrease at Post30Min from 392.53±146.63 to 329.40±49.80 mm (p=0.014) and a new significant decrease at Post24H from 367.80±83.67 to 302.91±70.88 mm (p<0.001); however, the experimental group showed similar values for all measurements (p>0.05). In between-group analysis, significant differences were found at Post0Min when the experimental group showed lower values than the control group (392.53±146.63 mm vs 325.06±83.44 mm, p=0.030). Results close to the level of significance were observed at Post6H (p=0.068).

Velocityr showed a main time effect (p<0.001) and a statistically significant group*time interaction (p=0.032). In within-group analysis, the control group showed a decrease at Post30Min from 24.51±6.65 mm/sec at baseline to 19.53±3.70 mm/sec (p=0.001), a significant increase at Post6H from 19.27±2.63 to 23.33±5.84 mm/sec (p=0.024), and another decrease at Post24H from 23.33±5.84 to 19.09±4.62 mm/sec (p<0.001). In between-group analysis, significant differences were observed at Post0Min, when the experimental group showed lower values than the control group (24.51±6.65 vs 19.96±4.74 mm, p=0.021). Significant results were also observed at Post6H (23.33±5.84 vs 20.04±3.77 mm/sec, p=0.046). The main time effects in Lengthr and Velocityr showed that both groups had significantly lower values with respect to Pre at all measurements except that of Post0Min one. The other variables did not show any significant group*time interactions (p>0.05).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of the present study was to analyze the short-term effects of a proprioceptive training session with unstable platforms on the monopodal stability of athletes. To this end, athletes were subjected to a monopodal stabilometry test before a 25-minute proprioceptive session and then 5 times more: right after the training, after 30 minutes, after 1 hour, after 6 hours and after 24 hours from the end of the proprioceptive training session.

Important findings were observed in variables refering to position of CoP in both the mediolateral and anteroposterior directions of the experimental group (Xmean and Ymean). The control group experienced several and important fluctuations in the mediplateral and anteroposterior directions during the 24 hours after the conventional warm-up session in left-side monopodal support. These fluctuations were not observed in the experimental group, which showed values over the whole time. These findings agree with the study of Romero-Franco et al., in which the control group showed worse stabilometric parameters with certain fluctuations in mediolateral stability after a 25-minute warm-up16). In contrast, Subasi et al., reported that a shorter warm-up had positive effects on the balance of healthy young individuals, without any difference between a 5-minute and a 10-minute warm up20). Regarding the uniformity of stabilometric parameters of the experimental group, the only study to date, to our knowledge, which has analyzed immediate effects of proprioceptive training on stability did not find similar results, only a certain deterioration in mediolateral stability16).

All differences found between the experimental and control groups on both the left and right-side monopodal supports were always in favour of the experimental athletes, who showed values closer to zero than the control group, and consequently, a more central position of CoP in the anteroposterior and mediolateral directions of left-side monopodal support and in the anteroposterior direction of right-side monopodal support. In spite of these between-group differences, no clear stabilometric improvement was shown in the mediolateral and anteroposterior stability after the proprioceptive training session. Our findings partly agree with Romero-Franco et al., who showed that a proprioceptive training session had no effect on most stabilometric parameters of athletes16). They also reported a certain deterioration in the mediolateral stability in bipodal support after proprioceptive training, which would have been distinct from our results, where no changes were observed in the experimental group.

Regarding variables about the path covered by CoP, significant findings were observed in Length and Velocity of the right-side monopodal stabilometry. Both the experimental and control groups experienced a stabilometric improvement after the training session, and this improvement was higher in the experimental group after the proprioceptive training. Our findings differ from Romero-Franco et al. who reported deterioration in bipodal stability right after a proprioceptive training session16). The difference between our results and those of Romero-Franco et al. seems to mean that the effects of proprioceptive training are different for the cases of monopodal and bipodal support. This result could be explained by Ashton-Miller’s suggestion about the specific improvement proprioceptive training often induces, which means that only similar exercises are improved21). This would explain the difference between the result of the present study and those of Romero-Franco et al., since proprioceptive training in both studies comprised mainly monopodal exercises. This explanation would also support the study of Paterno et al., in which athletes showed improvements in anteroposterior and general stability, but not in mediolateral stability in monopodal support after six weeks of proprioceptive training. Paterno et al. suggested that these results may have been due to the lack of mediolateral perturbation during their proprioceptive training program, which only consisted of anteroposterior perturbations1).

In the present study significant fluctuations were found in the stabilometric values of the control group after the warm-up session, while the experimental group showed similar values for all measurements after the proprioceptive training session.

Despite the fact that no clear stabilometric improvement was found during the 24 hours after the proprioceptive training session, the uniformity observed in the stabilometric values of the experimental group may mean the proprioceptive training session had a stabilizing effect on stabilometry. Thus, taking into account the consensus about stabilometric deterioration as a risk factor of injuries22,23,24), a more stable CoP without significant fluctuations would appear to be extremely important for injury prevention. However, further investigation is needed to verify this supposition.

Also, we suggest that differences found between right and left-side monopodal support may be explained by the sense of the curve of the track where all the athletes participing in this study trained, which is always to the left, according to the coaches of all athletes. However, no studies to date have analysed the effect of this on athletes.

This study had limitations that need to be considered. First, the size sample was small, which could have affect the limits of significance. Also, the athletes’ inexperience with proprioceptive training may have been the main cause why clear improvements in monopodal stability did not appear. In futher investigations, we recommend the inclusion of a group of athletes experienced in proprioceptive training, in order to analyze its immediate effect and detail the best schedule for a training routine.

The inclusion of a 25-minute proprioceptive training session on unstable platfoms after a conventional warm-up by athletes stabilized the position of CoP in the anteroposterior and mediolateral planes in monopodal stability by decreasing CoP displacement. Contrary to our hypothesis, after 25-minutes of conventional warm-up, athletes showed stabilometric alterations. However, the inclusion of an additional 25-minute proprioceptive training on unstable platforms helped to regulate monopodal stabilometric parameters in the short-term mantaining the monopodal stability level of athletes.

In practical application, coaches and physiotherapists should taken into account the “stable stabilometry” gained immediately after the proprioceptive training which eliminates significant stabilometric fluctuations which could be a potential risk factor of injuries for athletes. Besides, the incorporation of proprioceptive exercises as part of the warm-up would not only result in better stability than a typical warm-up, but would also elicit medium and long-term improvements in stability that are essential for injury prevention.

References

- 1.Paterno MV, Myer GD, Ford KR, et al. : Neuromuscular training improves single-limb stability in young female athletes. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther, 2004, 34: 305–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arokoski JP, Valta T, Airaksinen O, et al. : Back and abdominal muscle function during stabilization exercises. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2001, 82: 1089–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGill SM, Grenier S, Kavcic N, et al. : Coordination of muscle activity to assure stability of the lumbar spine. J Electromyogr Kinesiol, 2003, 13: 353–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chulvi I, Heredia JR. Acondicionamiento Deportivo: Análisis del trabajo con Fitball para el fortalecimiento de la zona Media. Alto rendimiento: ciencia deportiva, entrenamiento y fitness. 2006. 31: 3.

- 5.Behm D, Colado JC: The effectiveness of resistance training using unstable surfaces and devices for rehabilitation. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 2012, 7: 226–241 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattacola CG, Lloyd JW: Effects of a 6-week strength and proprioception training program on measures of dynamic balance: a single-case design. J Athl Train, 1997, 32: 127–135 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stanton R, Reaburn PR, Humphries B: The effect of short-term Swiss ball training on core stability and running economy. J Strength Cond Res, 2004, 18: 522–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yaggie JA, Campbell BM: Effects of balance training on selected skills. J Strength Cond Res, 2006, 20: 422–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero-Franco N, Martinez-Lopez E, Lomas-Vega R, et al. : Effects of proprioceptive training program on core stability and center of gravity control in sprinters. J Strength Cond Res, 2012, 26: 2071–2077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yasuda T, Nakagawa T, Inoue H, et al. : The role of the labyrinth, proprioception and plantar mechanosensors in the maintenance of an upright posture. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol, 1999, 256: S27–S32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall P, Murphy B: Changes in muscle activity and perceived exertion during exercises performed on a swiss ball. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab, 2006, 31: 376–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson KG, Behm DG: Maintenance of EMG activity and loss of force output with instability. J Strength Cond Res, 2004, 18: 637–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson K, Behm DG: Trunk muscle activity increases with unstable squat movements. Can J Appl Physiol, 2005, 30: 33–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drinkwater EJ, Pritchett EJ, Behm DG: Effect of instability and resistance on unintentional squat-lifting kinetics. Int J Sports Physiol Perform, 2007, 2: 400–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McArdle W, Katch F, Katch V: Fundamentos de fisiología del ejercicio. 2nd Edición. Mardrid: McGrawHill-interamericana. 2004

- 16.Romero-Franco N, Martinez-Lopez E, Lomas-Vega R, et al. : Short-term effects of proprioceptive training with unstable platform on athletes’ stabilometry. J Strength Cond Res, 2013, 27: 2189–2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mundial AM. Declaración de Helsinki de la Asociación Médica Mundial. Principios éticos para las investigaciones médicas en seres humanos.[Internet]. 2008

- 18.Spalding A, Kelly L, Santopietro J, et al. : Kids on the ball: using Swiss balls in a complete fitness program: Human Kinetics; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Behm DG, Anderson K, Curnew RS: Muscle force and activation under stable and unstable conditions. J Strength Cond Res, 2002, 16: 416–422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subasi SS, Gelecek N, Aksakoglu G: Effects of different warm-up periods on knee proprioception and balance in healthy young individuals. J Sport Rehabil, 2008, 17: 186–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashton-Miller JA, Wojtys EM, Huston LJ, et al. : Can proprioception really be improved by exercises? Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc, 2001, 9: 128–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tropp H, Ekstrand J, Gillquist J: Stabilometry in functional instability of the ankle and its value in predicting injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc, 1984, 16: 64–66 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trojian TH, McKeag DB: Single leg balance test to identify risk of ankle sprains. Br J Sports Med, 2006, 40: 610–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang HK, Chen CH, Shiang TY, et al. : Risk-factor analysis of high school basketball-player ankle injuries: a prospective controlled cohort study evaluating postural sway, ankle strength, and flexibility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil, 2006, 87: 821–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]