Abstract

Few dermatologic complaints carry as much emotional overtones as hair loss. Adding to the patient's worry may be prior frustrating experiences with physicians, who trivialize hair loss. A detailed patient history, physical examination and few pertinent screening blood tests usually establish a specific diagnosis. Once the diagnosis is certain, treatment appropriate for that diagnosis is likely to control the problem. Treatment options are available, though limited, in terms of indications and efficacy. Success depends both on comprehensions of the underlying pathology and on unpatronizing sympathy from the part of the physician. Ultimately, patients need to be educated about the basics of the hair cycle and why considerable patience is required for effective cosmetic recovery. Communication is an important component of patient care. For a successful encounter at an office visit, one needs to be sure that the patient's key concerns have been addressed. Physicians should recognize that alopecia goes well beyond the simple physical aspects of hair loss. Patients’ psychological reactions to hair loss are less related to physicians’ ratings than to patients’ own perceptions. Some of the patients have difficulties adjusting to hair loss. The best way to alleviate the emotional distress is to eliminate the hair disease that is causing it. Treatment success relies on patient compliance. Rather than being the patient's failure, patient non-compliance results from failure of the physician to ensure confidence and motivation. Finally, patients with hypochondriacal, body dysmorphic, somatoform, or personality disorders remain difficult to manage. The physician should be careful not to be judgmental or scolding because this may rapidly close down communication. The influence of the prescribing physician should be kept in mind, since inspiring confidence versus scepticism and fear clearly impacts the outcome of treatment. Sometimes the patient gains therapeutic benefit just from venting concerns in a safe environment with a caring physician.

Keywords: Communication skills, difficult patient encounter, hair loss, nocebo reaction, patient non-compliance

INTRODUCTION

Try not to become a man of success, but rather try to become a man of value.

–Albert Einstein

Few dermatologic problems carry as much emotional overtones as the complaint of hair loss, especially in the female patient. Adding to the patient's worry may be prior frustrating experiences with physicians, who tend to trivialize complaints of hair loss. This attitude on the part of physicians may result form a lack of knowledge making them feel uncomfortable in dealing with the complaint of hair loss, which is then readily discarded as a negligible medical problem. Even if the complaint may seem disproportionate to the extent of recognizable hair loss, the proportion of women suffering of true imaginary hair loss is small. Moreover, hair loss may be a symptom of a more general medical problem that needs to be investigated appropriately.

A detailed patient history focussing on chronology of events, examination of the scalp and pattern of hair loss, a simple pull test, dermoscopy of the scalp and hair, few pertinent screening blood tests and a scalp biopsy in selected cases will usually establish a specific diagnosis.[1]

Once a diagnosis is certain, appropriate treatment is likely to control hair loss, though with limitations in terms of indications and efficacy. Therefore, patient education about the basics of the hair cycle, what may be expected from treatment and why considerable patience is required for effective cosmetic recovery is paramount.

PREREQUISITES FOR SUCCESSFUL MANAGEMENT OF HAIR LOSS

It is easier to write a prescription than to come to an understanding with the patient.

–Franz Kafka, A Country Doctor

Prerequisites for successful management of hair loss are twofold: On the technical and on the psychological level.

On the technical level, prerequisites for success are: A specific diagnosis, a profound understanding of the underlying pathophysiology, the best available evidence gained from the scientific method for clinical decision making and regular follow-up of the patient combining standardized global photographic assessments and epiluminiscence microscopic photography with or without computer-assisted image analysis. With respect to the diagnosis one must remain open minded for the possibility of a multitude of cause-relationships underlying hair loss and therefore also for the possibility of combined treatments and multitargeted approaches to hair loss. With respect to the practice of evidence-based medicine, one must remain aware of the fact that good medical practice means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external evidence from evidence-based medicine.

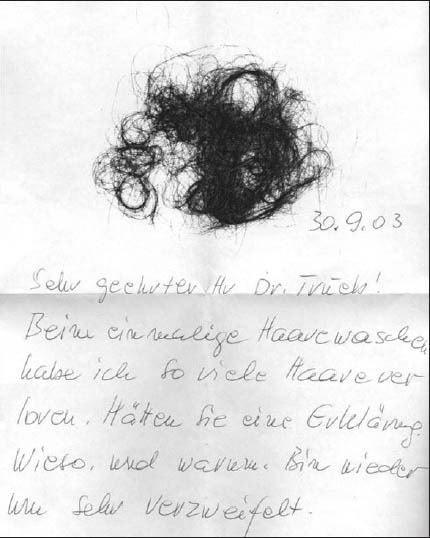

On the psychological level, for a successful encounter at an office visit, one must be sure that the patient's key concerns have been directly and specifically solicited and addressed: Acknowledge the patient's perspective on the hair loss problem, explore patient's expectations from treatment and educate patients into the basics of the hair cycle and why patience is required for effective cosmetic recovery. One must recognize the psychological impact of hair loss.[2,3,4,5] Physicians should recognize that alopecia goes well beyond the simple physical aspects of hair loss. Patients’ psychological reactions to hair loss are less related to physicians’ ratings than to patients’ own perceptions. Some patients have difficulties adjusting to hair loss. The best way to alleviate the emotional distress is to eliminate the hair disorder that is causing it. Only a minority of patients suffer from true imaginary hair loss. These have varied underlying mental disorders ranging from overvalued ideas [Figure 1] to delusional disorder. In these cases, one must aim at making a specific psychopathologic diagnosis.[6]

Figure 1.

Letter from female patient with overvalued ideas regarding hair loss

The difficult patient can be defined as one who impedes the clinician's ability to establish a therapeutic relationship.[7] Data from physician surveys suggest that nearly one out of six out-patient visits are considered as difficult.

The recent past has seen an increase in the study of the difficult patient, with the literature warning against viewing the patient as the only cause of the problem. It suggests, rather, that the clinician-patient relationship constitutes the proper focus for understanding and managing difficult patient encounters. Therefore, communication between clinician and patient is a key factor in understanding and caring for patients who are perceived to be difficult.[8,9,10]

Probably, the most frequent cause for difficult patient encounters are prior negative patient experiences with physicians, others are specific psychopathological disorders related to the somatic complaint, that again have to be identified as such.

COMMUNICATION SKILLS

The man of breed shuns a loud speech and a fast pace.

–Confucius, Analects

Communication is an important part of patient care and has a significant impact on the patient's well-being: Successful communication is the main reason for patient satisfaction and treatment success, whereas failed communication is the main reason for patient dissatisfaction, irrespective of treatment success.

Communication skills are not a question of talent. Communication skills can be improved through training and through experience, though traditionally, communication in medical school curricula is incorporated informally as part of rounds and faculty feedback but without a specific focus on skills of communication. Basically, communication skills require a genuine interest in the problem of hair loss (on the technical level) and a genuine interest in the patient (on the psychological level).

Communication with the patient has to include:

Listening to the patient

Understanding the patient

Informing the patient on: Diagnostic procedures, diagnosis. therapeutic considerations and prognosis

Convincing the patient

Giving the patient hope

Leading the patient to take personal responsibility

Jointly rejoicing over therapeutic progress.

Avoid:

Precipitance/hecticness

A personal dominant behavior

Stereotype prejudices.

PSYCHOPATHOLOGICAL DISORDERS

The educated among the physicians make an effort into an understanding of the mind.

–Aristotle, Nicomachic Ethics

There remain a number of psychopathological conditions related to the complaint of hair loss. The clinician must keep in mind that the distress the patient feels from having a hair disease can be handled both dermatologically and psychologically.

The most frequent mental disorder related to hair loss are the adjustment disorders, either with depressed mood, anxiety and/or disturbance of conduct, somatic and/or sexual dysfunction and feelings of guilt and/or obsession. From a psychopathological point of view, adjustment disorders result form the stressful event of hair loss, depending on its acuity, extent and prognosis. The intensity of the distress that the patient feels should be part of the clinician's formula in deciding how aggressively to treat the hair disorder, irrespective of the clinical recognizable extent of hair loss.

The more challenging psychopathological disorders that may be related to difficult patients encounters are the somatoform disorders (conversion disorder, somatoform pain disorder, hypochondriacal disorder and body dysmorphic disorder) and the personality disorders (anxious, negativistic, histrionic and paranoid).

In imaginary hair loss or psychogenic pseudoeffluvium, patients are frightened of the possibility of going bald, without any objective findings of hair loss. These patients only make up for a minority of female patients complaining of hair loss, but the spectrum of underlying psychopathology is wide, with a majority at the neurotic end of the spectrum with merely overvalued ideas about their hair, whereas a minority of patients suffer from true delusional disorder. The most common underlying psychiatric disorders are: Depressive disorder and body dysmorphic disorder. Differential diagnosis is particularly challenging, since there is considerable overlap between hair loss and psychological problems, with lower self-confidence, higher depression scores, greater introversion, higher neuroticism and feelings of being unattractive.

The patient with hypochondriacal disorder has no real illness but is overly obsessed over normal bodily functions. They read into the sensations of these normal bodily functions the presence of a feared illness. Due to misinterpreting bodily symptoms, then become preoccupied with ideas or fear of serious illness, whereas appropriate medical investigation and reassurance do not relieve these ideas. These ideas cause distress that is clinically important or impairs work, social, or personal functioning. The disorder usually develops in middle age or later and tends to run a chronic course.

Patients with body dysmorphic disorder probably represent the most difficult of patients for the dermatologist in practice.[11] The patient becomes preoccupied with a non-existent or minimal cosmetic defect and persistently seeks medical attention to correct it. This preoccupation again causes distress that is clinically important or impairs work, social, or personal functioning. The disorder tends to occur in younger adults. One of the various theories attempting to make the disorder understandable is the self-discrepancy theory, in which affected patients present conflicting self-beliefs with discrepancies between their actual and desired self. Media-induced factors are considered to predispose to the disorder by establishing role models for beauty and attractiveness.

Although Thersites complex is but another term used synonymously for body dysmorphic disorder, named after Thersites who was the ugliest soldier in Odysseus’ army, according to Homer, the more recently described Dorian Gray syndrome probably represents a variant of the body dysmorphic disorder, in which patients wish to remain forever young and seek life-style drugs (including hair growth promoting agents) and surgery to deter the natural aging process, named after Dorian Gray, the protagonist of the respective Oscar Wilde novel.[12]

Finally, patients with a personality disorder may have a negative impact on the clinician's ability to establish a therapeutic relationship. In the case of an anxious, negativistic, histrionic, or paranoid patient, it is important never to be judgemental or scolding because this may rapidly close down communication. The patient gains therapeutic benefit just from venting concerns in a safe environment with a caring physician.

NOCEBO REACTION

In a strict sense, a nocebo reaction refers to undesirable effects subject experiences after receiving an inert dummy drug or placebo.[13] Nocebo reactions are not chemically generated and are due only to the subject's pessimistic belief and expectation that treatment will produce negative consequences. In a wider sense, the term is being increasingly used for unexpected negative reactions to an active drug.

The influence of the prescribing physician should be kept in mind, since inspiring confidence versus scepticism and fear clearly impacts the outcome of treatment. Nevertheless, some patients with somatoform disorder and specific personality disorders, e.g. anxious, negativistic, histrionic, or paranoid, are more prone to nocebo reactions and should be recognized as such.

In general, nocebo reactions are observed more frequently in women and the older age group.

PATIENT NON-COMPLIANCE

Treatment success relies on patient compliance that, on its part, relies on confidence and motivation. Non-compliance is a major obstacle to the delivery of effective hair loss treatment. More often than being a failure of the patient, patient non-compliance results from failure of the physician to ensure that essential confidence and motivation for successful treatment. Patient compliance and therapeutic success rely on comprehension of treatment benefit, confidence and motivation.[14,15,16]

Major barriers to patient compliance are:

Denial of the problem

Lack of comprehension of treatment benefits

Occurrence or fear of side effects

Cost of the treatment

Complexity of treatment regimen

Poor previous experience

Poor communication and lack of trust

Neglect and forgetfulness.

Recommendations for improvement of patient compliance are:

Only recommending treatments that are effective in circumstances they are required

Prescribing the minimum number of different medications, for example, combining active ingredients into a single compound

Simplifying dosage regimen by selecting different treatment or using a preparation that needs fewer doses during the day

Selecting treatment with lower levels of side effects or fewer concerns for long-term risks

Discussing possible side-effects and whether it is important to continue medication regardless of those effects

Advising on minimizing or coping with side effects

Regular follow-up for reassurance on drug safety and treatment benefits

Developing trust so patients don’t fear embarrassment or anger if unable to take a particular drug, allowing the doctor to propose a more acceptable alternative.

A positive physician-patient relationship and regular follow-up visits are the most important factors in determining the degree of patient compliance. The overall goal is to gain short-term compliance as a prerequisite to long-term adherence to treatment:[17]

Short-term compliance issues addressed by the physician within the first 3 months of therapy are: Winning the patient's confidence in the diagnosis and treatment plan and detecting problems relating to the prescribed treatment regimen, or drug tolerance.

Long-term compliance issues addressed at 6, 12 months of follow-up and thereafter yearly are: Treatment efficacy and sustainability, long-term toxicities and treatment costs.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Tuto, celeriter, iucunde (Latin for: safely, swiftly, gladly)

–Asclepiades of Bithynia

Asclepiades of Bithynia (124-56 BC) was the personal physician and near friend of notable personalities of Ancient Rome, such as Cicero and Marc Anthony.[18] While the foreign Greek physicians were originally encountered with distrust by the Romans and especially its aristocracy, Asclepiades managed to convince through his high learning, brilliant medical achievements and worldly wisdom. Above all, he was attentive and sympathetic to the individual needs of his patients. Ultimately, Asclepiades advocated humane treatment of mental disorders. The same way Asclepiades won the Roman populace and aristocracy for his cause, the physician caring for patients complaining of hair loss must advance to build his reputation and to secure the confidence of his patients. A liaison with patients, respect for their individuality and professional expertise are preliminary toward creating an atmosphere of trust, which, on one side, enables physician's professional contribution to the somatic healing process and on the other side, assists patients to draw also from their own mental healing capacities.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Trüeb RM. Heidelberg, Berlin: Springer; 2013. Female Alopecia: Guide to Successful Management. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckert J. Diffuse hair loss and psychiatric disturbance. Acta Derm Venereol. 1975;55:147–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cash TF, Price VH, Savin RC. Psychological effects of androgenetic alopecia on women: Comparisons with balding men and with female control subjects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:568–75. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(93)70223-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maffei C, Fossati A, Rinaldi F, Riva E. Personality disorders and psychopathologic symptoms in patients with androgenetic alopecia. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:868–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cash TF. The psychosocial consequences of androgenetic alopecia: A review of the research literature. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:398–405. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.03030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trüeb RM. Psychodermatology of the hair and scalp. In: Blume-Peytavi U, Tosti A, Whiting D, Trueb R, editors. Hair Growth and Disorders. Berlin: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keller V, White MK, Carroll JG, Segal E. West Haven, CT: Bayer Institute for Health Care Communication; 1995. “Difficult” Physician-Patient Relationships Workbook. [Google Scholar]

- 8.White MK, Keller V, Carroll JG. West Haven, CT: Bayer Institute for Health Care Communication; 1995. Physician-Patient Communication Workbook. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teutsch C. Patient-doctor communication. Med Clin North Am. 2003;87:1115–45. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(03)00066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neumann M, Scheffer C, Tauschel D, Lutz G, Wirtz M, Edelhäuser F. Physician empathy: Definition, outcome-relevance and its measurement in patient care and medical education. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2012;29:Doc11. doi: 10.3205/zma000781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cotterill JA. Body dysmorphic disorder. Dermatol Clin. 1996;14:457–63. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70373-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brosig B, Kupfer J, Niemeier V, Gieler U. The “Dorian Gray Syndrome”: Psychodynamic need for hair growth restorers and other “fountains of youth.”. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2001;39:279–83. doi: 10.5414/cpp39279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kennedy WP. The nocebo reaction. Med World. 1961;95:203–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marinker M, Shaw J. Not to be taken as directed. BMJ. 2003;326:348–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7385.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngoh LN. Health literacy: A barrier to pharmacist-patient communication and medication adherence. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2009;49:e132–46. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.07075. 147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stone MS, Bronkesh SJ, Gerbarg ZB, Wood SD. Improving Patient Compliance. Strategic Medicine. 1998. Jan, Available from: http://www.patientcompliancemedia.com/Improving_Patient_Compliance_article.pdf .

- 17.Geneva: WHO; 2003. World Health Organization. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rawson E. The life and death of Asclepiades of Bithynia. Class Q. 1982;32:358–70. doi: 10.1017/s0009838800026549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]