Abstract

One in three adults in India uses tobacco, a highly addictive substance in one or other form. In addition to prevention of tobacco use, offering evidence-based cessation services to dependent tobacco users constitutes an important approach in addressing this serious public health problem. A combination of behavioral methods and pharmacotherapy has shown the most optimal results in tobacco dependence treatment. Among currently available pharmacological agents, drugs that preferentially act on the α4 β2-nicotinic acetyl choline receptor like varenicline and cytisine appear to have relatively better cessation outcomes. These drugs are in general well tolerated and have minimal drug interactions. The odds of quitting tobacco use are at the very least doubled with the use of partial agonists compared with placebo and the outcomes are also superior when compared to nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion. The poor availability of partial agonists and specifically the cost of varenicline, as well as the lack of safety data for cytisine has limited their use world over, particularly in developing countries. Evidence for the benefit of partial agonists is more robust for smoking rather than smokeless forms of tobacco. Although more studies are needed to demonstrate their effectiveness in different populations of tobacco users, present literature supports the use of partial agonists in addition to behavioral methods for optimal outcome in tobacco dependence.

Keywords: Cessation, cytisine, tobacco dependence, varenicline

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco, a human created epidemic is a major cause of preventable death and disease in the world. Nearly 35% of adults in India use some form of tobacco. India, with a population of 1.2 billion, currently has around 275 million tobacco users. Smokeless tobacco (SLT) use is more common than smoking. Morbidity and mortality related to tobacco use are both very high across the world, more so in developing countries. Smoking has been associated with reduction of median survival rate by 6-8 years. Tobacco-related mortality in India is among the highest in the world and 930,000 adult deaths in India were forecast due to smoking alone for 2010.[1,2] Excess deaths among smokers, as compared with non-smokers, were chiefly from tuberculosis and respiratory, vascular or neoplastic diseases.[1] A recent large hospital based study from urban India has shown that current smokers have a relative risk (RR) of almost 4.7 times compared to never smoker for acute myocardial infarction.[3] Although there is no systematic study, it is estimated that 8.3 million cases of coronary artery disease and chronic obstructive airway diseases are also attributable to tobacco each year.[4]

TOBACCO CESSATION

Quitting tobacco at any stage of life in a tobacco user is known to be beneficial. The risk of cardiac events, blood pressure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), oropharyngeal cancer/precancerous lesion etc., decreases substantially and the risks become comparable with the non-smoker over the next 1 year following quitting. Smokers who quit before 50 years of age reduce their risk of dying in the next 15 years to half that of a continuing smoker.[5] This holds true for pregnancy. If a potential mother quits smoking before becoming pregnant or within the first trimester of pregnancy, infant birth weight is likely to be the same as a non-smoker.[4,5]

However, quitting tobacco is not easy. Tobacco is easily available in various forms and its use is culturally well accepted. Nicotine, the active ingredient of tobacco, is highly addictive. Spontaneous quit attempts are very low. While a significant percentage of smokers have considered quitting, it has been suggested that only 2% of users quit on their own.[1]

Tobacco cessation for a current tobacco user (most of whom are dependent) needs a proactive approach and provision of support for a quit attempt. Most meta-analytical studies evaluating tobacco cessation interventions recommend a combination of pharmacotherapy with behavioral interventions. Pharmacotherapy has been shown to double or triple quit rates.[6,7]

There is a limited range of pharmacological options available for tobacco cessation. These broadly include nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and non-nicotine therapies such as bupropion, nortriptyline and varenicline. The focus of this paper is on partial selective nicotine receptor agonist drugs.

Varenicline has been available since 2006, but its high cost has been a barrier for its wider use even in countries where there is insurance coverage.[8] Another inexpensive drug with a similar mechanism of action, cytisine, which has been prescribed for smoking cessation in Eastern European countries for nearly five decades (absence of any standard drug trial data) has recently drawn wider interest.[8,9]

PARTIAL SELECTIVE NICOTINE RECEPTOR AGONISTS

Craving, a core feature of nicotine dependence, is an important cause for multiple relapses. Partial and selective nicotine receptor agonists have shown promising results for tobacco cessation. At this time, there are three agents in this group, i.e. Varenicline, Cytisine and Dianicline.

Search methods

We searched Google Scholar, PubMed, Cochrane database, by using the following MeSH and key words, i.e. “Varenicline”, “Champix”, “Chantix”, “Cytisine”, “Tabex”, “Dianicline”, “partial nicotine agonists” in the title and/or abstract.

We could identify 517 publications in PubMed, 960 publications in Google Scholar for Varenicline and 50 publications in PubMed, 140 publications in Google Scholar for Cytisine during the year 2005-2013. There were six Cochrane reviews on partial nicotine receptor agonist/pharmacological intervention for nicotine dependence.[10,11,12] We could come across five references for Diancline as the drug development has been discontinued. For this review, we have considered the latest studies including the meta-analysis, systemic reviews and Cochrane data base and excluded pre-clinical/animal trials and studies reported in non-English languages.

MECHANISM OF ACTION

Nicotine is the main addictive chemical in tobacco. Its interaction with neuronal nicotinic acetyl choline receptors (nAChRs) leads to activation and release of various neurotransmitters, i.e. noradrenaline, acetylcholine (Ach), gamma-aminobutyric acid, dopamine and glutamate. Hence nicotine modifies a large number of physiological processes such as locomotion, nociception, anxiety, learning and memory.[13] nAChRs are a heterogeneous family of ligand-gated cation channels present in the central nervous system and in the peripheral nervous system. The heteromeric α4 β2-nAChR is most widespread and densely present in the ventral tegmental area of the midbrain.[14] In the rat brain, this receptor accounts for more than 90% of high-affinity binding of the nicotine.[15] The area of particular interest for nicotine addiction is nAChR expressed in mesocorticolimbic pathway, i.e. nucleus accumbens to ventral tegmental region, extending to frontal area. This area is also known as the reward system and is modulated by dopamine release. This release of the dopamine is associated with intense pleasure and a sense of relief. This reinforces the process of nicotine addiction.[16]

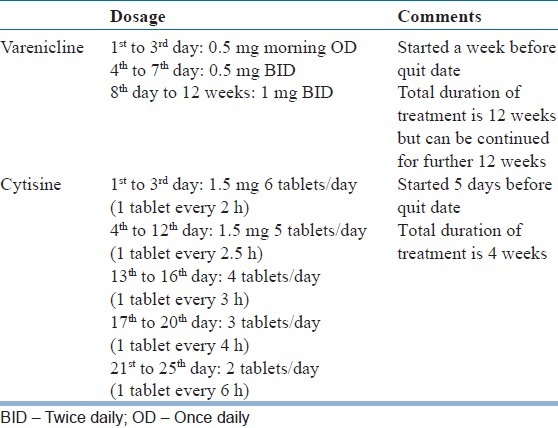

Varenicline, Cytisine and Dianicline have been classified as selective partial agonists at the human α4 β2-nAChR receptors. Selective means these drugs preferentially activate functions of human α4 β2-nAChR receptors at lower concentration than required to activate other human nAChR receptor subtypes. Partial agonist means the magnitude of response following interaction with these receptors is lower than the pure agonists, i.e. nicotine or Ach.[17] Partial nicotine receptor agonists help people to stop smoking both by maintaining moderate levels of dopamine to counteract withdrawal symptoms (acting as an agonist) and reducing smoking satisfaction (acting as an antagonist) in case the person smokes. The dose and duration of use of Varenicline and Cytisine is mentioned in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Dosage and administration

VARENICLINE

Varenicline is a α4 β2 selective nicotinic receptor partial agonist and has been approved for use in nicotine addiction since 2006 and is available in India since 2008.

Clinical studies among smokers

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses collating data from 15 randomized controlled trials (RCT) studies involving more than 6000 people recommend that varenicline is effective for smoking.[10] Continuous or sustained abstinence at 6 months or longer for varenicline at standard dosage versus placebo showed an RR of 2.27 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.02-2.55)[11] and odds ratio (OR) of 2.88 (95% CI: 2.40-3.47).[12] A low or variable dose of varenicline was twice more effective than placebo.

In another study, in comparison with bupropion, the abstinence rate at the end of 1 year with varenicline was 1.52 (95% CI: 1.22-1.88, 3 RCT, 1622 people). Varenicline was found to be slightly superior to single forms of NRT in two trials, with an RR of 1.13 (95% CI: 0.94-1.35; 2 trials, 778 people)[11] but was not more effective than combination NRT.[12]

In a recent naturalistic study where minimal professional support was offered in routine care, the odds of being abstinent was 1.76 (CI: 1.23-2.53) with varenicline compared with NRT.[18] Similar results, i.e. an OR of 2.03 (95% CI: 1.46-2.82), have been reported at 52 weeks abstinence with varenicline compared to NRT.[19]

A recent study on effectiveness of varenicline among smokers from Asian populations (China, India, Philippines and Korea) showed that overall 46.4% of people successfully quit smoking by the end of treatment phase at week 12.[20]

Varenicline has very good oral bioavailability and is not affected by food or time of the day. It has low protein binding (<20%) and is hence it is safe in older age. It is not metabolized by the hepatic cytochromal system (CYP) and is excreted almost unchanged in the urine. There is no dose adjustment required for mild to moderate renal impairment. Varenicline does not have any meaningful pharmacokinetic drug interactions with concomitant use of medications including with drugs having narrow therapeutic index like digoxin or warfarin.[21]

Varenicline is generally well-tolerated. The most common side effect with varenicline is nausea. Gastrointestinal side effects, i.e. flatulence, nausea and vomiting can occur in approximately 8-40% of patients. Other common adverse effects include headache, insomnia and abnormal dreams.

Soon after its introduction, there was concern regarding two important side effects, i.e. neuropsychiatric and cardiovascular (CV) events.

Neuropsychiatric adverse effects

In 2008, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported serious neuropsychiatric symptoms among patients treated with varenicline and also issued a black box warning. These symptoms include changes in behavior, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal ideation. As per the FDA data, a total of 147 cases of suicidal thought (n = 110) or behavior (n = 37) were reported in association with varenicline use. However, a recent meta-analysis (11 clinical trials with over 10,000 participants, 7000 of whom received varenicline) and post-marketing surveillance (80,660 smokers attempting to quit, 10,973 with varenicline) did not show any increased psychiatric or behavioral change. The mood changes are comparable to that with NRT.[22,23]

There is a very small increase in the possibility of neuropsychiatric side-effects. This is more significant in patients having existing or family history of affective disorders. However at the same time, this (rare) concern need not discourage physicians from prescribing this effective medication.[24] A latest reanalysis of data from 17 RCTs (N: 8027) did not show any evidence of increase risk of neuropsychiatric adverse effects in individuals with or without a recent history of psychiatric disorder.[25]

CV side effects

There is increase in reports of serious CV events with varenicline use. A meta-analysis reported a small but statistically significant rise in serious CV adverse events, i.e. ischemia, arrhythmia, congestive heart failure, sudden death or CV-related death in subjects receiving varenicline.[26] However reanalysis of the data did not show support for any significant increase in the risk of treatment emergent, CV serious adverse events (SAEs) attributed to varenicline use.[27] In view of the low absolute increase in risk for serious CV events, compared with the large benefit for smoking cessation, current opinion appears to suggest varenicline may be used in stable CV disease.

CYTISINE

Cytisine, probably the world's oldest anti-smoking medication was discovered as early as 1818. This is an alkaloid with a high affinity for the nicotinic receptor α4 β2 and is derived from the plant Cytisus laburnum. The leaves of this plant were used by people when tobacco was not available. This observation that Cytisine satisfies smoker led to its development in a tablet form, i.e. Tabex in 1964. Since then, it is being prescribed and used in Eastern European countries like Bulgaria and Poland.[17,28]

Recently there is a surge of literature advocating use of this inexpensive medication in settings where other treatments are not affordable.

Clinical studies

Unlike varenicline, cytisine has been in clinical use without passing through phases of an investigational drug development, i.e. clinical trials studies.

Pre-clinical

Behavioural studies in animals have pointed out that the effect of cytisine is similar to those of nicotine except that it does not produce the same degree of behavioral activation like nicotine. The behavioral activation is measured by ambulatory activities of the animal. The reinforcing or reward effect due to cytisine is not well studied except that drug naïve mice would self-administer cytisine intravenously.[17,29]

Clinical

The first placebo controlled trial of cytisine was published from Eastern Europe in 1968. Until 1984, there were four more trials and two of them were RCTs.[30,31,32,33,34] The outcome and follow-up duration was mostly 12 weeks and with minimal (standards) behavioral intervention. The study population size of these placebo controlled RCTs varied from 200 to 600. All these studies reported that cytisine is significantly more effective than placebo. Validated objective outcome measures, i.e. carbon monoxide (CO) or urine cotinine tests were not used in those studies. These studies largely went unnoticed as these papers are published in non-English language (mostly German).[17]

The most influential study which has generated a lot of interest in cytisine was published in NEJM in 2011.[35] A recent meta-analysis, including seven RCTs, reported that cytisine was significantly more effective than the comparators, i.e. RR = 1.59; 95% CI: 1.43-1.75. In two recent studies, cytisine was significantly more effective than placebo, increasing the chance of successful quitting more than threefold (RR = 3.29; 95% CI: 1.84-5.90).[35,36] These two studies are of 6 months to 1 year follow-up[35] and have used validated outcome estimators like CO estimation and cotinine tests as outcome markers. The study by West et al. (2011) is similar to a Phase III drug trial.[35]

Safety

The safety data, i.e. adverse drug reactions or SAEs for cytisine do not exist as it has not been studied systematically unlike in other drug development. This drug has been used in thousands of smokers for the last four decades without any report of SAEs.[17] The clinical studies did not show any significant differences between cytisine and placebo in SAEs, headache, insomnia or nausea. The amount of cytisine sold in Bulgaria in the year 2006 was 78,846 courses (one course is 100 tablets) compared to 21,187 of NRT. In the meta-analysis, the most frequent reported side effect was gastrointestinal compared to placebo.[9]

In a few of the previous studies, there were reports of serious adverse events like renal pain, one rhabdomyolysis, two suicide attempts by overdose. The data on blood pressure and heart rate are contradictory.

NICOTINE RECEPTOR AGONISTS IN SPECIFIC CONDITIONS

There have been limited studies on use of varenicline in other forms of nicotine addiction and in comorbid physical conditions.

SLT use

SLT use like Khaini, Gutkha etc., is common among the general population in India. Studies on effectiveness of varenicline are predominantly derived from smokers. A 12 week study from India[37] on SLT has reported significant higher self-reported abstinence among patients who were on varenicline than placebo (43% vs. 31%; adjusted OR = 2.6, 95% CI: 1.2-4.2, P = 0.009), although this significance was lost when urine cotinine measures were considered. Thus participants in this study were likely to have under-reported their tobacco use during the follow-up. Treatment adherence to varenicline as well as placebo was <40% and drop-out rate from both the treatment arms was around 50%. Greater adherence to medication among those treated with varenicline was associated with significantly greater confirmed SLT abstinence rates and a greater likelihood for recovery to abstinence following a lapse, but not for placebo. The findings of the study point towards difficulty in adherence as well as compliance to treatment among SLT users. In contrast, an RCT among 431 SLT (snus: Tobacco powder covered in a small absorbable paper and kept under the lip) users from Sweden, varenicline was found superior to placebo, both with self-report as well as biochemical findings. The continuous abstinence rate (abstinence in last 4 weeks) at 9-12 week was 59% for the varenicline and 39% for the placebo group (RR: 1.60, 95% CI: 1.32-1.87, P < 0.001). The benefit also persisted through the next 14 weeks of follow-up (varenicline 45% vs. placebo 34%; RR: 1.42, 1.08-1.79, P = 0.012).[38] There was no significant association of adverse effects (including neuropsychiatric and cardiac)- among the patients receiving varenicline.[37,38]

In summary, effectiveness of varenicline for SLT dependence is not as robust as for smoking.

Light tobacco users (smokers/chewers)

In one study of a population of young smokers, predominantly female and from a high socio-economic status who smoke less (fewer than one cigarettes per day [CPD]) and light (one to nine CPD) smokers.[39] Even such light smokers had a substantial failure rate in spite of being motivated to quit and with use of NRT. A study has shown that as high as 65% failed in their most recent quit attempt within 6 months.[39]

Most of the trials on varenicline have included moderate to heavy smokers, i.e. users of 10-15 cigarettes/day. It is common in clinical practice to have people who smoke few cigarettes (<10 cigarettes) but still find very difficult to quit in view of intense craving and conditioned cues. A pilot study conducted on Latino smokers reported 30% abstinence rate among varenicline users compared with NRT at 3rd and 6th month follow-up.[40] Another observational study has reported the odds of quitting increases twice at the end of 1 month with varenicline. There is a lack of studies among light SLT users.

Co-morbid medical illness

Tobacco use has been associated with multiple health hazards such as COPD, CV illness, malignancy etc.

In a multi-centered study, 504 patients with mild to moderate COPD were randomized to either varenicline or placebo for 3 months and followed-up for the next 40 weeks (i.e. a total duration of 52 weeks). The continuous abstinence rate was significantly higher in varenicline than placebo (18.6% vs. 5.6%) from week 9 to 52. Apart from common side-effects, there were no serious neuropsychiatric side-effects with varenicline.[41,42]

A multi-centered, placebo controlled RCT among 714 smokers with stable CV status reported significant benefits with varenicline than placebo. The odds of quitting among patients receiving varenicline was 6.11. An important finding is that varenicline did not increase CV events or mortality.[6]

Psychiatric illness

Effectiveness and tolerability of varenicline among patients having severe mental illness, i.e. schizophrenia or bipolar disorder has not been studied extensively. Case reports and retrospective chart reviews have reported mixed findings with regard to exacerbation of neuropsychiatric side-effects. One recent open label study on 112 stable schizophrenia patients showed the effectiveness of varenicline at the end of 12 weeks without any worsening of psychotic symptoms. All these patients also received weekly structured cognitive behavior therapy apart from the varenicline. Absence of a placebo or comparative treatment arm is a limitation of this study. A 12 week prospective placebo controlled RCT, initially showed a marginally significant benefit with varenicline at the end of 12 weeks which did not sustain at the end of 24 weeks. There was no increase in neuropsychiatric side-effects including suicide compared with placebo.[43]

There is an urgent need for more prospective studies in this group with regard to effectiveness as well as safety. Varenicline use among patients with psychiatric illnesses needs careful, periodic monitoring.

DISCUSSION

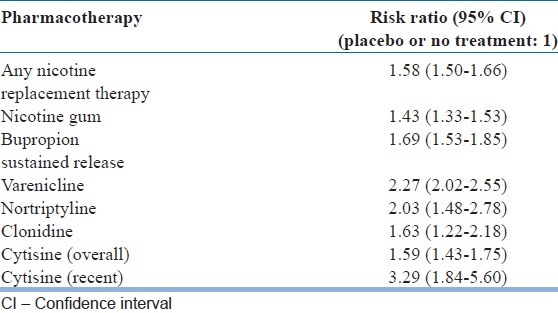

Tobacco dependence is a public health epidemic and its control is of utmost importance. The combination of pharmacotherapy and behavioral intervention is relatively more effective. Addition of pharmacotherapy, at the very least, doubles the chance of quitting. This is relevant in developing countries where there is presently a lack of adequate trained manpower to deliver behavior counseling for substance use disorders.[44] With the available literature, nicotine receptor partial agonist drug, i.e. varenicline and cytisine increase the chance of quitting at least twice or more which is relatively more than with other presently available pharmacotherapies [Table 2].[6,7,9]

Table 2.

Comparison of effectiveness of various types of treatment available for nicotine dependence

Treatment cost including that of medication has been an important concern throughout the world, including in developed countries like the USA. In the USA, which follows a co-paying insurance system and spends 16% of gross domestic product on health care, the increasing cost of treating chronic diseases has been a matter of concern.[45] In a review of more than hundred studies, the authors found a clear relationship between patient cost sharing, adherence to treatment and outcome. Approximately 85% studies showed that an increasing patient cost share of medication costs was significantly associated with a decrease in adherence. This inverse relationship of increase in cost and decrease in adherence holds true, irrespective of type of payments.[46]

Pharmacoeconomic studies show that cost of the beneficial effects of smoking cessation outperforms the cost of the varenicline.[47] At the same time, this is the costliest treatment available for the nicotine addiction.[28] Cytisine is widely available in the widely grown plant laburnum and therefore inexpensive to manufacture.[8]

However, there are some challenges in the use of cytisine at this point which warrant more studies. The two important ones are frequent dosing (6 times a day at the beginning) and the need of at least one large scale study to establish the safety and tolerability. However having a detailed and extensive drug trial (pre-clinical, Phases I to III) will delay the products. Few of the issues can also be addressed by a good post-marketing surveillance (Phase IV) and a standard pharmacovigilance method.[8]

Cytisine is a potentially effective and an affordable addition in the management of smoking if it can be brought to the market early. As pointed out in a recent editorial,[28] government should take the initiative to fund at least one large scale clinical study for this effective medication and getting its approved by regulatory authorities for wider use. This will also prevent the possibility of poor quality and counterfeit formulations from online buying.[8,28] In the current scenario, many people will continue to die or suffer from sequelae of smoking related diseases around the world and being deprived of this cheap and effective medication. This holds greater relevance for rural, poor and developing countries where tobacco is a growing problem.[8]

CONCLUSION

In the present day, nicotine receptor partial agonists represent the most promising pharmacotherapeutic agents for tobacco cessation. There are several trials establishing the effectiveness and safety of varenicline in tobacco, particularly smoking cessation. There is some evidence for its effectiveness for SLT cessation. However, the cost of varenicline limits its use on a wider scale. Considering the public health impact of tobacco use, it is necessary to subsidize such treatments if they are to be widely used. Cytisine is an old drug that has been shown to be cost-effective and can be a viable alternative if large scale safety data can be generated.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jha P, Jacob B, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, Dhingra N, Kumar R, et al. A nationally representative case-control study of smoking and death in India. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1137–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0707719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gajalakshmi V, Peto R, Kanaka TS, Jha P. Smoking and mortality from tuberculosis and other diseases in India: Retrospective study of 43000 adult male deaths and 35000 controls. Lancet. 2003;362:507–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rastogi T, Jha P, Reddy KS, Prabhakaran D, Spiegelman D, Stampfer MJ, et al. Bidi and cigarette smoking and risk of acute myocardial infarction among males in urban India. Tob Control. 2005;14:356–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.011965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murthy P, Saddichha S. Tobacco cessation services in India: Recent developments and the need for expansion. Indian J Cancer. 2010;47(Suppl 1):69–74. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.63873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, US: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. Services USDoHaH. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rigotti NA. Strategies to help a smoker who is struggling to quit. JAMA. 2012;308:1573–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.2008 PHS Guideline Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive summary. Respir Care. 2008;53:1217–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aveyard P, West R. Cytisine and the failure to market and regulate for human health. Thorax. 2013;68:989. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hajek P, McRobbie H, Myers K. Efficacy of cytisine in helping smokers quit: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2013;68:1037–42. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahill K, Stead LF, Lancaster T. Nicotine receptor partial agonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD006103. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006103.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: An overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD009329. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009329.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berrendero F, Robledo P, Trigo JM, Martín-García E, Maldonado R. Neurobiological mechanisms involved in nicotine dependence and reward: Participation of the endogenous opioid system. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:220–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albuquerque EX, Pereira EF, Alkondon M, Rogers SW. Mammalian nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: From structure to function. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:73–120. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00015.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Benowitz NL. Pharmacology of nicotine: Addiction and therapeutics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:597–613. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benowitz NL. Nicotine addiction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2295–303. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0809890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etter JF. Cytisine for smoking cessation: A literature review and a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1553–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotz D, Brown J, West R. Effectiveness of varenicline versus nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation with minimal professional support: Evidence from an English population study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;231:37–42. doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kralikova E, Kmetova A, Stepankova L, Zvolska K, Davis R, West R. Fifty-two-week continuous abstinence rates of smokers being treated with varenicline versus nicotine replacement therapy. Addiction. 2013;108:1497–502. doi: 10.1111/add.12219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang C, Cho B, Xiao D, Wajsbrot D, Park PW. Effectiveness and safety of varenicline as an aid to smoking cessation: Results of an inter-Asian observational study in real-world clinical practice. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:469–76. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Faessel HM, Obach RS, Rollema H, Ravva P, Williams KE, Burstein AH. A review of the clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of varenicline for smoking cessation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010;49:799–816. doi: 10.2165/11537850-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunnell D, Irvine D, Wise L, Davies C, Martin RM. Varenicline and suicidal behaviour: A cohort study based on data from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2009;339:b3805. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonstad S, Davies S, Flammer M, Russ C, Hughes J. Psychiatric adverse events in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials of varenicline: A pooled analysis. Drug Saf. 2010;33:289–301. doi: 10.2165/11319180-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aveyard P, McRobbie H, Stapleton J, West R. Varenicline: Effectiveness and safety. National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gibbons RD, Mann JJ. Varenicline, smoking cessation, and neuropsychiatric adverse events. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1460–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12121599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh S, Loke YK, Spangler JG, Furberg CD. Risk of serious adverse cardiovascular events associated with varenicline: A systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2011;183:1359–66. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.110218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prochaska JJ, Hilton JF. Risk of cardiovascular serious adverse events associated with varenicline use for tobacco cessation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e2856. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e2856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prochaska JJ, Das S, Benowitz NL. Cytisine, the world's oldest smoking cessation aid. BMJ. 2013;347:f5198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f5198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rasmussen T, Swedberg MD. Reinforcing effects of nicotinic compounds: Intravenous self-administration in drug-naive mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1998;60:567–73. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(98)00003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scharfenberg G, Benndorf S, Kempe G. Cytisine (Tabex) as a pharmaceutical aid in stopping smoking. Dtsch Gesundheitsw. 1971;26:463–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paun D, Franze J. Breaking the smoking habit using cytisin containing “Tabex” tablets. Dtsch Gesundheitsw. 1968;23:2088–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoyanov S, Yanachkova M. Tabex-therapeutic efficacy and tolerance. Savr Med. 1972;6:31–3. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stoyanov S, Yanachkova M. Treatment of nicotinism with the Bulgarian drug Tabex. Chimpharm. 1965;2:13. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennodorf S, Kempe G, Scharfenberg G, Wendekamm R, Winkelvoss E. Results of the smoking-habit breaking using cytisin (Tabex) I. Dtsch Gesundheitsw. 1968;23:2092–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.West R, Zatonski W, Cedzynska M, Lewandowska D, Pazik J, Aveyard P, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of cytisine for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1193–200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vinnikov D, Brimkulov N, Burjubaeva A. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial of cytisine for smoking cessation in medium-dependent workers. J Smok Cessat. 2008;3:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jain R, Jhanjee S, Jain V, Gupta T, Mittal S, Goelz P, et al. A double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial of varenicline for smokeless tobacco dependence in India. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16:50–7. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fagerström K, Gilljam H, Metcalfe M, Tonstad S, Messig M. Stopping smokeless tobacco with varenicline: Randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c6549. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kotz D, Fidler J, West R. Very low rate and light smokers: Smoking patterns and cessation-related behaviour in England, 2006-11. Addiction. 2012;107:995–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Dios MA, Anderson BJ, Stanton C, Audet DA, Stein M. Project Impact: A pharmacotherapy pilot trial investigating the abstinence and treatment adherence of Latino light smokers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43:322–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tashkin DP, Rennard S, Hays JT, Ma W, Lawrence D, Lee TC. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in patients with mild to moderate COPD: A randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2011;139:591–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tønnesen P. Smoking cessation and COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22:37–43. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams JM. Varenicline should be used as a first-line treatment to help smokers with mental illness quit. J Dual Diagn. 2012;8:113–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thirthalli J, Chand PK. The implications of medication development in the treatment of substance use disorders in developing countries. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2009;22:274–80. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832a1dc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Catlin A, Cowan C, Heffler S, Washington B. National Health Expenditure Accounts Team. National health spending in 2005: The slowdown continues. Health Aff (Millwood) 2007;26:142–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eaddy MT, Cook CL, O’Day K, Burch SP, Cantrell CR. How patient cost-sharing trends affect adherence and outcomes: A literature review. P T. 2012;37:45–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keating GM, Lyseng-Williamson KA. Varenicline: A pharmacoeconomic review of its use as an aid to smoking cessation. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28:231–54. doi: 10.2165/11204380-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]